12 Mid-19th Century Reform Movements

Reform

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the United States was not unlike a teenager; struggling to develop its own self-identity. Or, Americans were not happy or content with what they had unleashed and so Americans sought to further define what it meant to be an American. Or, Americans sought to always better themselves and their society. of course, the big question about reform is how much of this stuff is about change for the betterment of society and how much of this stuff is about controlling society -a society that is increasingly made up of immigrants? The War of 1812 certainly was a factor so too was the end of the Agrarian Republic and the double shot to the gut with the deaths of Jefferson and Adams in 1826.

Massive reform movements swept the country -some having a lasting effect, while most were just temporary in consequence. Most of these reform movements were limited (or wildly popular) in the North and these reform movements affected women much more in the North than southern women. Remember, these reform movements took a back seat to volunteerism during the War.

Can the Republic Survive Industrialization?

Agriculture was slow, seasonal, and task-oriented. Even artisans worked when demand necessitated work, not in accordance with a clock. Some households worked for artisans producing parts of the whole and households were paid by each piece they produced not by the hours they worked. In the early 1800s, men such as Samuel Slater and Francis Cabot Lowell created spaces where workers would perform piecework under direct supervision. They hired primarily children and young women because they could be paid less than older men. Factory owners became wealthy and that resulted in the rise of a new socio-economic order that we recognize today. White collar workers such as accountants and managers were in demand as well as bank employees.

The Lowell Mill, and the Factory System, were so incredibly divergent from anything seen in the United States at that time:

“Francis Cabot Lowell was hardly alone in his efforts to build a cotton textile industry in America. His system, however, differed markedly from Philadelphia homespun or the craft-factory model used in Rhode Island. Lowell’s industrial order ‘came to dominate the cotton industry [and] marked a radical departure from all that had gone before. In his 1864 book, Samuel Batchedler contrasts Francis Cabot Lowell’s system with Samuel Slater’s Rhode Island system. Slater ran small spinning mills, using copies of the English machinery, while Lowell developed new machines for his large factory and did spinning and weaving under power all under one roof. Slater used the labor of local families while Lowell employed healthy young women, housed and fed at the company’s expense and paid wages in cash. Slater adhered to the old craft system while Lowell built labor-saving machines that required only a few weeks of training to master the repetitive tasks. Slater built small mills with a small number of spindles, while the mill at Waltham contained thousands of spindles and several looms watched over by hundreds of workers. The conservative Slater clung to his tried-and-true methods of production while Lowell leaped ahead with his modern factory using the machines of mass production. At Lowell’s mill raw cotton came in at one end and finished cloth left at the other.”[1]

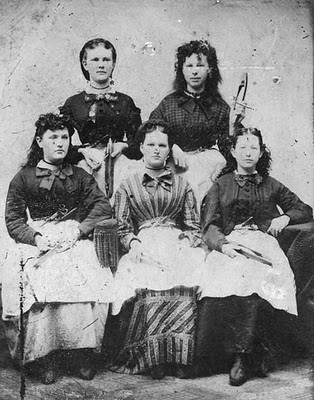

But Republicanism was still at the heart of what people felt about this nation so they feared losing Republicanism as a result of a shifting economy and the rise of a new social order. They would place the factories outside of cities and would supervise employees very carefully to stave off corruption, vice, and degradation. From that we see the development of the Boston Factory System: factories would be placed away from urban centers, workers would live as well as work in the factories, and people would be paid based on age, gender, and race. For example, at Slater’s Mill, older white men received the equivalent of $5 a week, $3 for older women, $2 for boys, and less than $2 for girls. Nonwhite workers and foreign-born workers received even less. But before the Irish showed up in massive numbers, American factories hired women:

“The Lowell System required hiring of young (usually single) women between the ages of 15 and 35. Single women were chosen because they could be paid less than men, thus increasing corporate profits and because they could be more easily controlled than men. These mill girls, as they were called, were required to live in company-owned dormitories adjacent to the mill and were expected to adhere to the rather strict moral code of conduct espoused by Lowell. They were supervised by older women, called matrons, and were expected to work diligently and attend church and educational classes. The young women would work a grueling 80-hour work week. Lowell believed his system alleviated the deplorable working conditions he witnessed in England and helped him to keep a tight rein on his employees. By doing so, he cultivated employee loyalty, kept wages low, and assured his stockholders of accelerating profits. Although Lowell’s labor arrangement was highly discriminatory and paternalistic compared to modern standards, it was seen as revolutionary in its day. A large number of young mill girls went on to become librarians, teachers, social workers, etc., thanks in large part to the education they received while working at the mill; thus, the system did produce benefits for the workers and the larger society.”[2] In contrast, Sam Slater hired even younger girls, around seven, according to The Encyclopedia of the War of 1812, “who were exploited and often abused…Slater kept tight reins on his labor pool as well, but the young girls were harder to train and control than adult women.”[3]

Thomas Jefferson (and others) feared an entrenched proletariat, so the new industrialists went with temporary workers -girls and young women. This would preserve women’s traditional roles such as spinning and weaving but as they would eventually get married the workforce would be constantly turning over. But that meant that the mills would become substitute parents.

So was the motive really to save the Republic? No. There was an economic aspect as well: workers lived in dormitories and had to pay for things from their pillows to coals to keep them warm during the long winters.

Many contemporaries applauded this system as being able to have both a robust manufacturing system as well as preserving republican virtue. But much of the Boston Factory System was about social control. Skilled and unskilled workers had separate dormitories, bells called people to work and to breaks, counting houses closely watched over mills/factories. Women, after their shifts, were taught skills that would, hopefully, transform them into ladies. “It was a most authentic republican community” argued one factory worker. Charles Dickens, who denounced English manufacturing in his novels, supported the Boston Factory System. Buildings he noted were “fresh and charming”, girls were well dressed and clean, and women were taught manners and deportment. Alexander DeTouqueville on Manchester England, pondered the paradox of industry: factories were bad for the individual but good for the community. “From the filthy sewer, pure gold flows,” he wrote.

Around the dorms were planted grass, shrubs, and other greenery because it was “rural, pastoral and pleasant. But time sped up. There was a bell that called the workers to meal time. The bell called them to work and to sleep. And their days were long. One account from the Lowell mill had women working from 5am to 7pm with 30 minutes for breakfast and 30 minutes for dinner. Even very young girls worked 14 hours a day.

Early on, they were eager to work to earn money for the family, make a dowry, or send a sibling to school. Workers pursued intellectual interests such as publishing their own periodicals. “It was a most authentic Republican community,” one author declared.

Over time wages remained stagnant as the workers’ cost of living increased so they demanded better wages. The first “strike” (what they called a turnout) was in 1834 at the Lowell Mill due to a 15% reduction in wages. Two years later boarding house rents were increased and another turnout ensued. These were all unsuccessful. None of the early strikes alleviated the women’s deteriorating conditions. American workers were quickly replaced by foreign-born workers (primarily the Irish in the 1840s) and the social status fell while American views on factories changed. “They’re taking our jobs” was the sentiment of the time.

Religious Reform (The Second Great Awakening and Its Effects)

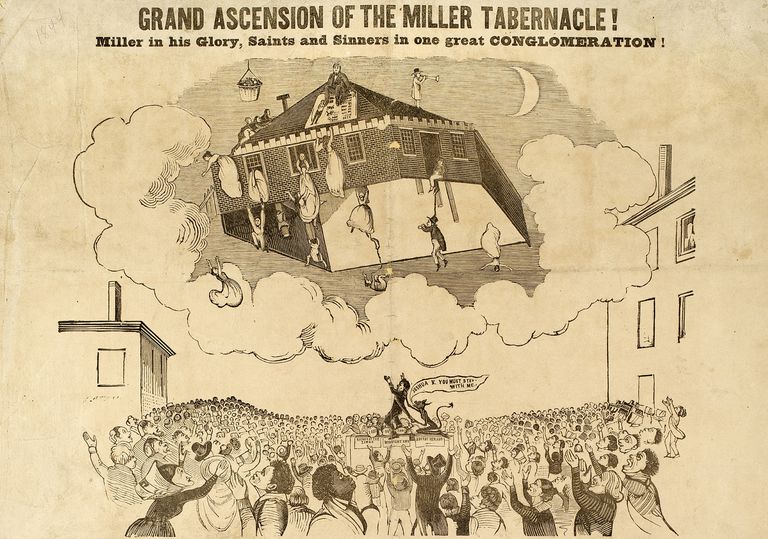

A wave of religious enthusiasm spread across the country, emanating from upstate New York, in the early part of the nineteenth century. New religions came into being, innovative ways of organizing society were attempted, and new ideas on gender relations and government-governed relationships were developed. This religious fervor had some common characteristics. First, religious leaders such as Joseph Smith and William Miller preached the perfectibility of individuals and the perfectibility of society. New religions came about such as the Mormons and older religions became much more popular such as the Baptists and the Unitarians. Many believed the end of the world would happen in their lifetime and thus they needed to prepare, such as William Miller (a one-time phrenologist) who believed he could determine the exact day of the second coming of Jesus. According to him, it was to be October 22nd, 1843. Although Miller was (spoiler alert) incorrect, his ideas on religions did result in the development of a new Protestant sect: the Seventh-Day Adventists. They believed that people could usher in the Second Coming through proper religious activities and women such as Ellen G. White played a role in establishing this new Christian sect and Clorinda Minor attempted to create a colony in Jerusalem in preparation for the Second Coming of Jesus.[4] Religious leaders preached that salvation was more of a choice than because of good works. Women, more so than the First Great Awakening, participated as evangelicals, as the emotionalism of the Second Great Awakening, was tied to the belief that women were more emotional (and religious) than men. The massive conversion of Africans (slave and free) to Christianity took place during the Second Great Awakening. One example of a female, free African preacher was Jarena Lee.

Lee later wrote about how the spirit moved her to preach and her early experiences as an itinerant preacher:

“I now began to think seriously of breaking up housekeeping and forsaking all to preach the everlasting Gospel. I felt a strong desire to return to the place of my nativity, at Cape May, after an absence of about fourteen years. To this place, where the heaviest cross was to be met with, the Lord sent me, as Saul of Tarsus was sent to Jerusalem, to preach the same gospel which he had neglected and despised before his conversion. I went by water, and on my passage was much distressed by sea sickness, so much so that I expected to have died, but such was not the will of the Lord respecting me. After I had disembarked, I proceeded on as opportunities offered toward where my mother lived. When within ten miles of that place, I appointed an evening meeting. There were a goodly number came out to hear. The Lord was pleased to give me light and liberty among the people. After the meeting, there came an elderly lady to me and said, she believed the Lord had rented me among them: she then appointed me another meeting there two weeks from that night. The next day I hastened forward to the place of my mother. who was happy to see me, and the happiness was mutual between us. With her, I left my poor sickly boy while I departed to do my Master’s will. In this neighborhood, I had an uncle, who was a Methodist and who gladly threw open his door for meetings to be held there. At the first meeting which I held at my uncle’s house, there was, with others who had come from curiosity to hear the woman preacher, an old man, who was a Deist, and who said he did not believe the colored people had any souls — he was sure they had none. He took a seat very near where I was standing, and boldly tried to look me out of countenance. But as I labored on in the best manner I was able, looking to God all the while, though it seemed to me I had but little liberty, yet there went an arrow from the bent bow of the gospel, and fastened in his till then an obdurate heart. After I had done speaking, he went out, and called the people around him, saying that my preaching might seem a small thing, yet be believed I had the worth of souls at heart. This language was different from what it was a little time before, as he now seemed to admit that colored people had souls, as it was to these I was chiefly speaking; and unless they had souls, whose good I had in view, his remark must have been without meaning. He now came into the house, and in the most friendly manner shook hands with me, saying, he hoped God had spared him for some good purpose. This man was a great slaveholder, and had been very cruel; thinking, nothing of knocking down a slave with a fence stake, or whatever might come to hand. From this time it was said of him that he became greatly altered in his ways for the better. At that time he was about seventy years old, his head as white as snow; but whether he became a converted man or not, I never heard.”[5]

Harriet Livermore was another “Pilgrim Stranger.”[6]

For as long as American history can be dated back to, women have been slowly breaking the generational curses of being submissive to a man. The mid-century reform was a positive exemplar of social change that was happening from the early-to-mid nineteenth century for the betterment of the people, especially women. This particular reform movement challenged the man’s traditional role of being the religious speaker by women like Harriet Livermore, preaching and making a statement in Christianity.[7]

Female preachers faced a lot of sexism and opposition from men and also women who believed in gender roles during this time in history, the Second Great Awakening. This is where women started getting themselves involved in voicing their faith, preaching the word of God to others. Between 1790 and 1845, during the revivals that historians have identified as the “Second Great Awakening,” more than one hundred women crisscrossed the country as itinerant preachers.[8] To us now, women preaching may seem normal, but before this period, that was never seen before nor accepted. Some argued that she was “bold and shameless, a disgrace to her family and to the evangelical movement.[9] The sexism in the church went as far as to say that women preaching was against the bible! Part of the reason evangelical women leaders are not mentioned vastly throughout history is that not many Christians wanted to remember them. Harriet Livermore’s story is typical; she rose to fame during the 1820s when several new sects allowed and even encouraged women to preach.[10] Throughout this reform, though some sects, like the Free-Will Baptists, were opening up opportunity, it did not mean the opposition ended here. Yet even though the largest, most influential churches forbade women to preach, the Congregationalists, the Presbyterians, and the Episcopalians, a small number of new, dissenting sects challenged the restrictions on women’s religious speech by allowing them into the pulpit.[11] By doing this, this reform movement allowed women to preach and express their love for God to others who are trying to find faith, which brought together men and women.

Despite all the struggles these influential women had to endure in order to make a statement, they continued to influence others and spread the faith. Women like Livermore became well known for their powerful preaching and pushing for women’s rights. She never settled into a single denomination, but instead focused on the task to “restore the apostolic simplicity of the primitive church.”[12] Female preaching in the mid-century reform was an eventful American era, where it challenged the traditional gender roles and religious beliefs. Though women faced harsh opposition from men and women who still believed in this ideology, these people made women like Livermore shape American history and paved the way for gender equality. The “Christian movement” encouraged women’s leadership in worship but did not ordain women. Some people rejected women’s leadership and labeled Livermore an “enthusiast,” “eccentric,” or “monomaniac.”[13] Harriet broke through the boundaries that separated the dual spheres between gender in a society where women were defined by their relationship to men.

Ivy League Universities and Religion[14]

There were two educational institutions’ direct religious’ beliefs that influenced politics, and the legal statutes that formed the Second Great Awakening. While providing evidence that the reform movement was for social betterment; however, it was also a competition between two social groups, their love of God, and the interpretation of the Bible through their lenses. The educational institutions of Harvard and Yale had differences in theologies. By the 1820s and 1830s, the revivals and their message of optimism and perfectionism stretched eastward. Converts to the new religious ways ardently strove to eliminate sin from themselves and their society. The Religious fervor had political implications that would overturn an inherited order based on hierarchy and coercion.[15]

The way each institute interpreted the Bible, is how to receive blessings from God. 1636, Massachusetts Bay colonists established Harvard College to train their ministers lest they leave the curse of an untrained ministry to their progeny.[16] Harvard was first a clergy school, so their ministers would teach their way. The basis of the reform movement influencers were God-fearing evangelist men of high-ranking elite and economic status in Massachusetts. One can characterize them as rising entrepreneurs whose close connection with country trade meant that personal reliability and responsibility relationships remained important.[17] The significance of this is the higher the class of men, the more effect they have on society to follow in their footsteps, for the betterment. The Congregationalism Liberals advocated an Enlightenment-influenced moralism in religion, which resulted in a de-emphasis on theology and ideological inclusivity.[18] For Sixty-five years, these men got along until theologies began to differ, and a rift came about. At the turn of the Century, the traditional Calvinistic leaders were alarmed that the parties of the most potent influence favored the new winds blowing and looked away from Boston to set up a new academic bastion of Calvinistic faith in 1700-01, which would be Yale.[19] In November 1753, the President and Fellows of Yale voted for the strict orthodox observance.[20] Now, the events that take place next begin the competition between these two ministries. A rift would surely follow 100 years of toleration.

In 1805, the first move to show the depth of the developing rift between the clergy of the two persuasions, conservatives, led by Connecticut-born and Yale-educated Jedidiah Morse, objected to the appointment of Henry Ware, a liberal, to the Hollis Professorship of Divinity at Harvard College.[21] Morse pulled together various conservative, Yale-educated clergy in the Boston area into a network of opposition to liberal opinions. He also mobilized the conservatives into rejecting fellowship with liberals.[22] Harvard, in the meantime, saw the appointment of a liberal clergyman as a president in the year following and became increasingly marked by a tendency to support only the liberal religious and cultural ethos.[23] Even though no formal denominational split had occurred between liberals and conservatives, it became increasingly clear that an alliance had formed among liberal religionists, Harvard College, and Boston’s elite business and mercantile interests.[24] These 200 years before the reform movement is essential because the information gives one a magnifying glass into why the evangelist created the reform movement for the betterment of society.

In the 1820s, the theological rift hardened into two different party lines. On the one hand, Congregationalists were primitivist in sympathy, despite a gradual modification of their stance in most cases to admit the possibility of human agency in accomplishing individual conversion. A rather striking departure from the most Calvinist practice of the prior Century.[25] Each, to the mind of the other, was responsible for the problems that plagued society-Unitarians, to the minds of Congregationalists, because they did not support the cause of true religion, which alone could bring about social order; Congregationalists, to Unitarians, because they were rigid and intolerant, refusing to allow the human mind latitude to reflect rationally on religious and social problems.[26] More than simply a quarrel over the beneficence or sovereignty of God, over the relative weights of reason and revelation in an enlightened religious sensibility, the Unitarian controversy involved the clash of two divergent cultures that had, until that moment, managed to see themselves as the same through reliance on a common tradition, vocabulary, and form of church polity.[27] A legal ruling in 1820, known as the Dedham decision, recognized the right of the majority in the parish (not just the church members) to church property, thus effectively disenfranchising conservatives in the Boston area. In 1825, the factions would never heal, and the liberals formed the American Unitarian Association, admitting that a formerly unified religious establishment had divided into two irreconcilable groups.[28]

Liberals emphasized getting along ethically with community members who might potentially hold differing beliefs. Despite the ongoing scrutiny from the Congregationalists, the liberals had no spokesperson for their cause. There is no one to be their voice until Newport, Rhode Island, born Harvard graduate and Pastor William Ellery Channing would become that voice. Channing’s views seen in his sermons, “not conscious of having contracted, in the least degree, the guilt of insincerity . . . .We have only followed a general system, which we are persuaded to be best for our people and the course of Christianity; the system excludes controversy as much as possible from our pulpits.”[29] Unitarianism was a pluralistic belief system premised on toleration, maintaining a social ethic of maximum inclusiveness, and self-culture more intent on maintaining institutional solid and civic leadership between groups.[30] The Unitarian elite was then responsible for the developing structures and networks of mercantile and industrial capitalism, including foreign trade, banking, insurance, and real estate. The predominated civic and governmental institutions were well-connected, well educated.[31] To the extent that they are involved with any organizational efforts, either religious or philanthropic, these were mainly educational endeavors meant to ensure the development of their learning in a variety of areas (not only, not especially theological and religious) designed to provide that the well-off met their obligations to attend with compassion to the poor.[32] When looking deeper, one can judge their view by their actions. The Unitarians built separate “chapels” that instituted a paternalistic “ministry to the poor” that attempted to maintain the ties of social obligation without integrating the poor into congregational life on an equal basis.[33]

On the other hand, conservative religious Pastor Lyman Beecher, born in New Haven and educated at Yale, can interpret Yale’s strict orthodox teachings. He would be the voice of the conservatives. Beecher saw Unitarianism as a perversion of true religion, as men of “stratagem and duplicity” who relied “upon wealth and the favor of the great” to advance their cause.[34] And These heirs to the original evangelists of the original colonies that of Massachusetts at Harvard were aggressively expansionists. Evangelicals like Beecher are bent on a strict discipline within the church, an adherence to well-defined standards, and a restoration as far as possible of a consensual, well-integrated, and ideologically homogeneous community. Beechers view on preaching the Bible the way he seemed fit, to lessen the degree of sin in society, for the overall betterment of society. One looks at Beecher and his view through his conservative upbringing. “Our fathers could enforce morality by law,” Beecher put it, “but the times are changed, and unless we can regulate public sentiment and secure morality in some other way, We are undone’.’ [35] This would be known as the “Code of laws” to the evangelist.

These two groups would continue down this bickering back and forth, carried out by pamphlets and in the newspapers at a time when print production and consumption were expanding.[36] The one similarity between the two is their views are based on their love of God and the Bible through their lens. Each was arguing about what they thought was for social betterment. The rise of evangelical influence in local, state, and national politics would influence all three branches of government, as legislative agendas now had to concede to the voting power of a religious block. These men from these distinguished universities were shaping and influencing society with their beliefs. While competing against one another, each was doing so for the betterment of reforming society. Once, the separation of a once liked-minded powerhouse that built the economic structure for America during the market revolution that mapped the roads to embark on national trade routes threw nobility out the window when it became about them and not the people. Cultural isomorphism is where a significant modification of a cultural order occurs, it causes changes in other aspects of the cultural mandate for creating a structure of an ontological organization for the culture.[37] The reform movement of the Second Great Awakening brought cultural change starting from religious beliefs that influenced politics. Thus, the way each institution interpreted the Bible, is how God receives the blessings from God to overall for the overall betterment of society.

Transcendentalists

Some sought refuge in nature. One such group was the Transcendentalists, popularized by such American writers such as William David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emily Dickinson and Margaret Fuller. They believed that traditional American ideas on politics and religion were corrupt so they performed a tactical retreat from American society by moving to the western areas of Massachusetts. Walden Pond is a classic example of a Transcendentalist community. There they promoted self-reliance and self-discipline. They supported the belief that people are best suited to make their own decisions about how they will organize their lives, not established religious or secular leaders. They were not atheists but rather believed that God wanted a personal relationship with individuals and that modernity (urbanization, industrialization, and commercialization) prevented that relationship from happening.

“Ralph Waldo Emerson, a former minister, was the central figure in a movement called transcendentalism. Emerson believed that every human being had unlimited potential. But to realize their godlike nature, people had to ‘transcend’ or go beyond purely logical thinking. They could find the answers to life’s mysteries only by learning to trust their emotions and intuition. Transcendentalists added to the spirit of reform by urging people to question society’s rules and institutions. Do not conform to others’ expectations, they said. If you want to find God–and your own true self–look to nature and the ‘God within.'”[38]

“The individuals most closely associated with this new way of thinking were connected loosely through a group known as The Transcendental Club which met in the Boston home of George and Sophia Ripley. Their chief publication was a periodical called “The Dial,” edited by Margaret Fuller, a political radical and feminist whose book “Women of the Nineteenth Century” was among the most famous of its time. The club had many extraordinary thinkers but accorded the leadership position to Ralph Waldo Emerson. Margaret Fuller played a large part in both the women’s and Transcendentalist movements. She helped plan the community at Brook Farm [led by George and Sophia Ripley], as well as editing The Dial, and writing the feminist treatise, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. Emerson was a Harvard-educated essayist and lecturer and is recognized as our first truly “American” thinker. In his most famous essay, “The American Scholar” he urged Americans to stop looking to Europe for inspiration and imitation and be themselves. He believed that people were naturally good and that everyone’s potential was limitless. He inspired his colleagues to look into themselves, into nature, into art, and through work for answers to life’s most perplexing questions. His intellectual contributions to the philosophy of transcendentalism inspired a uniquely American idealism and spirit of reform.”[39]

Utopian Societies

People attempted to flee the perceived excesses of American society -particularly industrialization. They were not anti-capitalists, they just believed in a more equitable distribution of wealth. Why should a factory owner become wealthy due to his workers when many believed that factory owners needed to pay their workers better, to better share in the economic success of those factories? Utopian societies were also rather Jeffersonian in the sense that they forwarded a return to nature or at least an emphasis on living within the frontier. They believed in local government and in a settler mentality of a more intimate community of like-minded people over urbanization. There were other issues in contemporary American society that concerned those who established and were drawn to Utopian communities.

Snow was Joseph Smith’s first, and legal, wife. Then married Brigham Young upon Smith’s death.

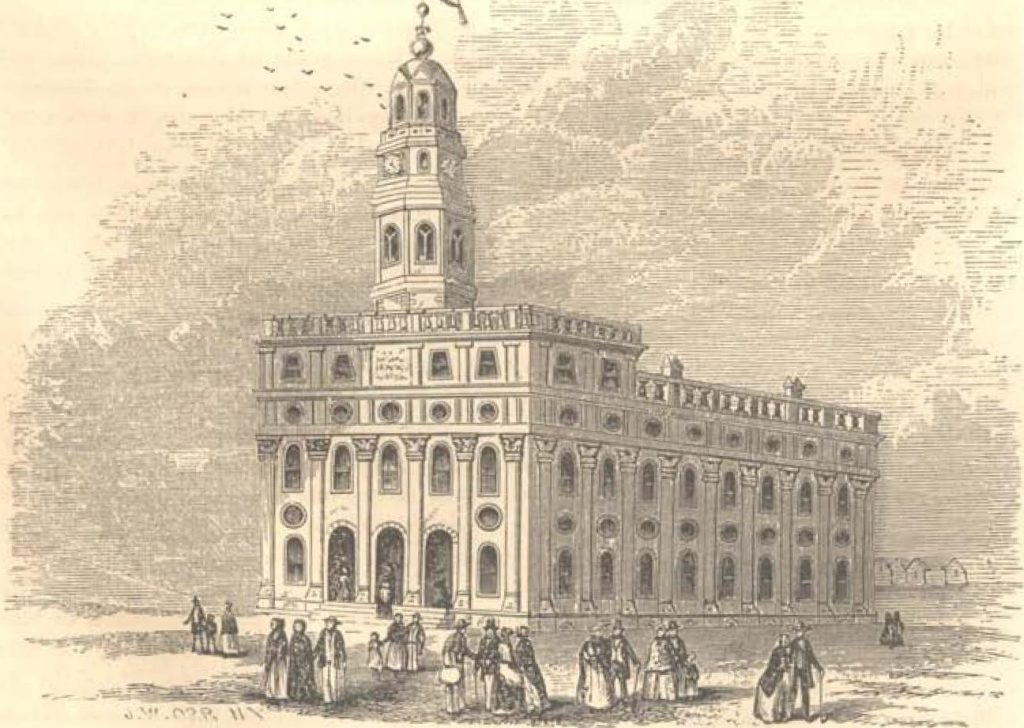

Mormonism[40]

Joseph Smith created Mormonism after a series of alleged discussions with an angel. He created a cooperative, closed, theocracy as himself as the religious leader (he called himself a prophet) and the secular leader. Mormons practiced polygamy, which in part will get his group pushed farther and farther West. He started his theocracy in New York but the community fled to Ohio, then Missouri, and finally in Illinois he tried to establish a community that would help usher in the Second Coming of Jesus. When Smith was killed, his lieutenant Brigham Young married all of Smith’s wives, declared himself another prophet, and took over as their religious and secular leader, then led his group to what is today Salt Lake City Utah. When Utah sought admittance into the US as a state, Congress initially refused due to Mormons’ practice of polygamy. So, church leaders denounced the practice, removed it from their list of beliefs, and Utah then became a state.

One of the most important events of early Mormon history is what unfolded at Nauvoo, Illinois. What follows is one explanation of those events and is found on the blog of Dr. Roger Launius:[41]

The non-Mormons of Hancock County, Illinois, in the early 1840s probably disliked the Mormons from the first, in the same way that most Americans have generally disliked what they have viewed as religious fanaticism, but they were initially disposed toward toleration because they sympathized with its members as refugees from oppression in Missouri. That view, however, soon began to change. Some of the Mormons, embittered against “Gentiles” (non-Mormons) because of their recent experience and impoverished because of their forced abandonment of homes in Missouri, stole food, livestock, and other things from farms in the Nauvoo area. And non-Mormons soon learned that trips to Nauvoo in search of stolen goods, or to seek payment for items sold to the Mormons, were fruitless—and even frightening.

The highly unified, separatist community did not cooperate with outsiders, and some of the Saints resorted to intimidation. For example the “whistling and whittling brigade” of young ruffians made unwelcome visitors fear for their lives as they encircled them during their visits to the Mormon stronghold. Nauvoo quickly developed a reputation among western Illinois residents as a place where lawbreakers friendly to the church were shielded from arrest.

The amount of Mormon theft is impossible to determine, since some stealing by others was undoubtedly blamed on the Saints, nor can Joseph Smith’s involvement be established with any certainty, despite what some memoirs fron older residents imply. Certain Mormon raiders may have felt they had Smith’s approval when in fact they did not. In any case, the evidence of Mormon theft is substantial, and that activity caused some non-Mormons in townships near Nauvoo to oppose the Saints.

But of far greater importance to the development of non-Mormon animosity and to the eventual eruption of mobocratic violence was the perceived threat to democratic government posed by Smith and his theocratic community. That view was expressed as far away as Macomb, Quincy, Alton, and other Illinois communities, but it was centered in Hancock County, where the Mormons dominated local politics by 1842.

Warsaw, a town of about 500 people in the early 1840s, spearheaded the opposition to Smith and political Mormonism. Founded in 1834 as a place for shipping and commerce, Warsaw was something of a microcosm of pluralistic America, an open, ambitious, progressive community where residents did not hold the religious preconceptions that made Nauvoo’s theocracy possible. Instead, local residents firmly subscribed to republicanism, the ill-defined civil religion of the Jacksonian era. Common democratic ideals lashed the people together, and the rituals of self-government affirmed the community’s ideological bond.

To the people of Warsaw, the nation had transcendent value, and republicanism was the operative faith of their town. So, it is not surprising that residents there objected to Smith’s theocratic domination of government at Nauvoo, his encouragement of bloc voting for candidates he supported, his use of the Nauvoo Charter to avoid prosecution, and, eventually, his violation of the civil rights of his critics.

That Joseph Smith also headed a huge militia, the Nauvoo Legion, made the threat of despotism seem all the more real. When a united political effort, the Anti-Mormon Party of 1841-1842, failed to curb Smith’s secular power, non-Mormons became increasingly frustrated, and there was talk of mobocratic measures to stop the threat of political Mormonism.

At the same time, after two arrest attempts by Missouri officials, the Mormon prophet became increasingly fearful of the authorities in that state, whom he regarded as thoroughly evil. He drew his supporters more closely around him by depicting the Saints as innocent chosen people and himself as their champion fighting the enemies of God. Critics and opponents in Illinois were associated with those enemies, and thus fear and intolerance increased among the Mormons and governmental authority at Nauvoo became centered in Smith. Apparently unaware of the contradiction between real democratic government and his theocratic control of Nauvoo, the prophet placed the church on a collision course with the non-Mormons in Hancock County—and, ultimately, with America.

No question, the conflict between the Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo and the residents surrounding Nauvoo, Illinois, in the 1840s is one of the most important aspects of early Mormon history. Controversies between the Mormon and non-Mormon population began almost immediately when the Latter -day Saints arrived in Illinois in 1839 and grew in intensity and violence by the middle-1840s. The assassination of Joseph Smith Jr. in 1844 and a Mormon war that only ended with the members’ removal from Illinois 1846 are only the two most visible aspects of this struggle.

By taking violent action the citizens of Hancock County reasserted fundamental direction over local government whether for good or ill. Political scientist Jurgen Habermas has suggested that when the “instrumental rationality” of the bureaucratic state intrudes too precipitously into the “lifeworld” of its citizenry, they rise up in some form to correct its course or to cast it off altogether. The “lifeworld” is evident in the ways in which language creates the contexts of interpretations of everyday circumstances, decisions, and actions. He argued that the “lifeworld” is “represented by a culturally transmitted and linguistically organized stock of interpretive patterns.” . . . Conflict of some kind seems inevitable in this context, and when Smith condemned his Mormon critics as enemies of the people and suppressed their civil rights through institutionalized violence, the non-Mormons—politically frustrated and fearing despotism—resorted to mobocratic measures. Other causes, such as lawlessness by some Mormons aimed at the Gentiles economic and social strife, contributed to the outbreak of violence, but in my view this ideological struggle was central.[42]

Amana

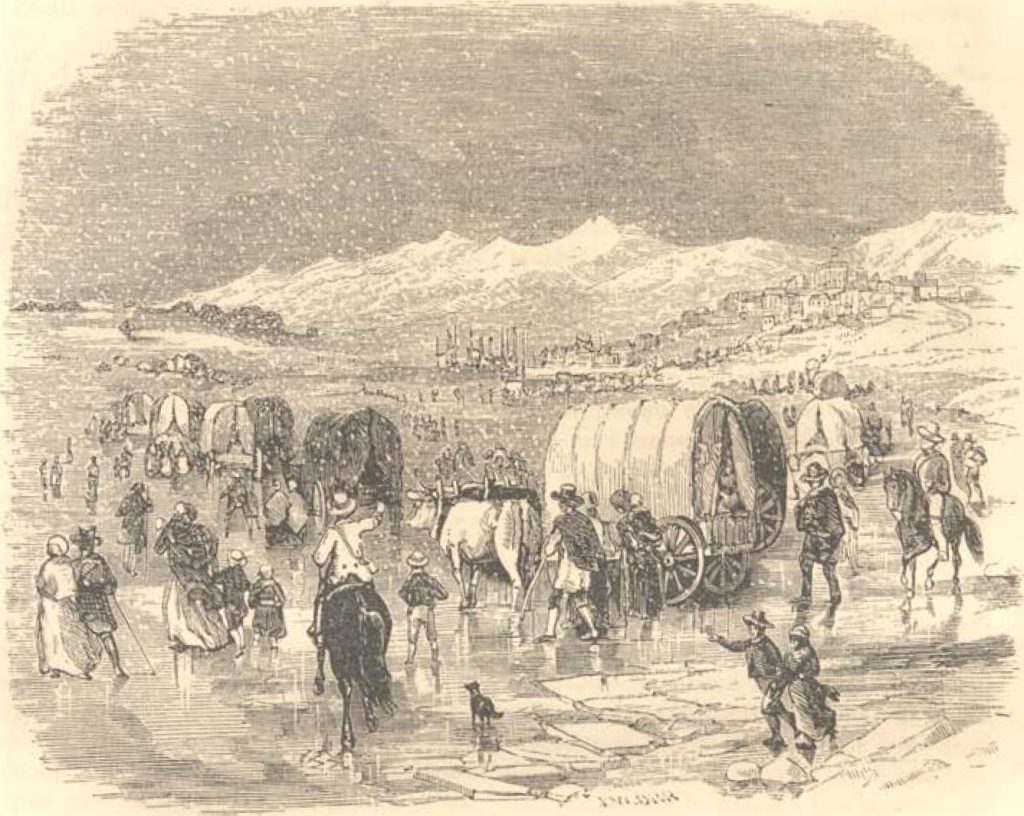

“The Amana origins trace back to early seventeenth century Germany within pietist circles in Wurtemberg and Hessen. Among the peasants and lower middle class emerged the “Community of True Inspiration” – a group of sectarians who believed that God could inspire people to speak. This sectarian community still believed in prophecies and the prophets or ‘werkzeuge’ (literally meaning instruments) would speak directly to God in leading their communities. During the early 1700’s the sect was led by two Werkzeuge named Eberhard Ludwig Gruber, a Lutheran minister, and Johann Frederick Rock, a harness maker and son of a Lutheran minister. Prompted by prophecies, the sect decided to search for a place of settlement in the United States. The first US settlement was set up in upstate New York in 1844. But eventually, neighboring communities such as Buffalo began to expand near the New York settlement so the leaders looked to move west to re-establish isolation which led to the establishment of the Amana Colonies in Iowa.”[43]

Calling themselves the “Community of True Inspiration,” German immigrants established a community in upstate New York they named Amana (named after a local First People). They embraced Pietism who believed that the Bible was the blueprint for society. They had 21 Rules to include:

- Obey, without reasoning, God, and through God your superiors.

- Count every word, thought, and work as done in the immediate presence of God, in sleeping and waking, eating, drinking, etc., and give Him at once an account of it, to see if all id done in His fear and love.

- Never think or speak of God without the deepest reverence, fear, and love, and therefore deal reverently with all spiritual things.[44]

There ideas on happiness can be derived from some of their 21 Rules:

- Study quiet, or serenity, within and without.

- Abandon self, with all its desires, knowledge and power.

- Be honest, sincere, and avoid all deceit and even secretiveness.

- Do not disturb your serenity or peace of mind – hence neither desire nor grieve.

- Live in love and pity toward your neighbor, and indulge neither anger nor impatience in your spirit.

- Have nothing to do with unholy and particularly with needless business affairs.

- Have no intercourse with worldly-minded men; never seek their society; speak little with them, and never without need; and then without fear and trembling.

- Therefore, what you have to do with such men do in haste; do not waste time in public places and worldly society, that you be not tempted and led away.

- Dinners, weddings, feasts, avoid entirely; at the best there is sin.[45]

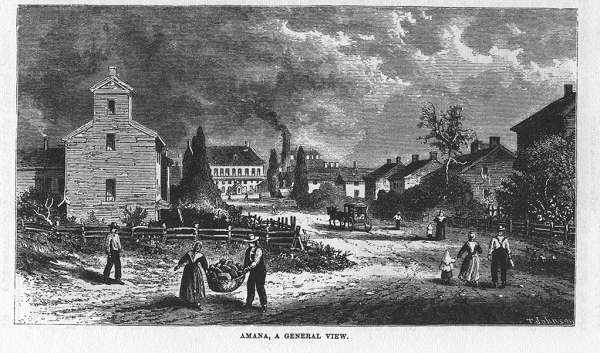

They repudiated all established churches and many established American institutions such as private property. The Amana community practices public ownership of all land and resources, to include its factory. Members of the original community near Buffalo New York moved to Iowa to build a new Utopian society. “Before dawn, a bell rang in the village tower called residents to work, and a simple church located in the center of town was available for daily worship. Children attended school six days a week, year round, until the age of 14. Then, boys worked on the farm or in craft shops, and girls worked in the garden or in one of the over 50 communal kitchens. Select boys were sent to college for training to be teachers, doctors, and dentists.”[46]

The Amana community made and sold kitchen utensils such as pots and pans. They were not anti-industry. They were anti-capitalists.

Oneida

John Humphrey Noyes, a theologian who was converted by Charles Finney, gave up his study of law and began preaching an unorthodox doctrine. He was expelled from mainstream churches. He supported perfectionism, intellectual pursuits over myth and magic, and that the mere conversion to Christianity was enough to secure your place in Heaven. He argued that traditional American society was made up of what he called systems: politics, religion, even marriage and that those systems prevented perfectionism. So, he started a community called Oneida (after a local First People) where he supported vegetarianism, communal ownership of property and complex marriage. He believed that traditional marriage resulted in women being at the mercy of men’s lust so in his Utopian society every woman was married to every man but sex was voluntary between any couple and he discouraged permanent unions. He also preached that men should restrain their lustful urges.

“Women over the age of 40 were to act as sexual ‘mentors’ to adolescent boys, as these relationships had minimal chance of conceiving. Furthermore, these women became religious role models for the young men. Likewise, older men often introduced young women to sex. Noyes often used his own judgment in determining the partnerships that would form, and would often encourage relationships between the non-devout and the devout in the community, in the hopes that the attitudes and behaviors of the devout would influence the non-devout.”[47]

“Every member of the community was subject to criticism by committee or the community as a whole, during a general meeting. The goal was to eliminate undesirable character traits. Various contemporary sources contend that Noyes himself was the subject of criticism, although less often and of probably less severe criticism than the rest of the community. Charles Nordhoff witnessed the following criticism of member “Charles:”

“The community believed that Jesus had already returned in AD 70, making it possible for them to bring about Jesus’s millennial kingdom themselves, and be free of sin and perfect in this world, not just Heaven (a belief called Perfectionism). The Oneida Community practiced communalism (in the sense of communal property and possessions), complex marriage, male continence, mutual criticism and ascending fellowship. There were smaller Noyesian communities in Wallingford, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersey; Putney and Cambridge, Vermont. The community’s original 87 members grew to 306 by 1878. The branches were closed in 1854 except for the Wallingford branch, which operated until devastated by a tornado in 1878.”[49]

To make money, the Oneida community made and sold flatware: forks, spoons, and knives. Eventually, he gave up on his systems theory, ended complex marriage, communal property was divided up and he sold stock in the community’s factory. They were not anti-industry. They were anti-capitalists.

The irony of the anti-capitalists, Amana and Oneida, is that although their Utopian communities failed, their factories succeeded, and today Amana and Oneida are two American corporations of kitchen stuff: from major appliances to cutlery.

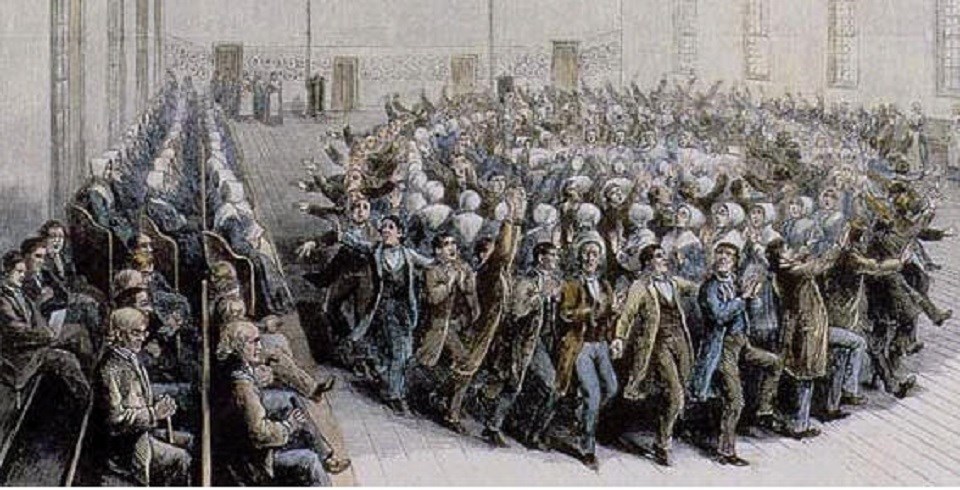

Shakers

The Shakers were unique in the sense that they were led by a woman named Mother Anne Lee Stanley. “In 1772, Lee received another vision from God. As described by Lee, ‘I knew that I had a vision of America, I saw a large tree, every leaf of which shown with such brightness as made it appear like a burning torch representing the Church of Christ which will yet be established in this land.’ Thus, in 1774, Ann Lee and nine of her followers traveled to America, settling in Western New York State. There, at Niskeyuna, the first American Shaker community was formed.”[50]

The name, Shaker, came from the physical manifestations in their religious rituals. She came from a poor family in England. Four of her children died and her conversion experience in the First Great Awakening was painful and long, lasting nine years. And although she died in 1784, her ideas continued. By 1800 there were about 12 Shaker communities in the US and during the Second Great Awakening, Shakers sent out their own evangelical preachers to build up the community’s population. Mother Anne Lee forwarded the idea that God was both male and female and was a millennialist who believed the end of the world was quickly coming. While Jesus was the male manifestation of God, she said she was the female manifestation of God. She preached equality between the sexes and demanded chastity, thus there was no way to make new Shakers, hence the evangelical nature of the religion during the Second Great Awakening. “The community meeting house was the center of Shaker worship services on Sunday. Spontaneous dancing was part of Shaker worship until the early 1800s when it was replaced by choreographed dancing. Spontaneous dancing returned around the 1840s, but by the end of the 19th-century dancing ceased during worship. Services consisted of singing hymns, testimonials, a short homily, and silence.”[51]

“Ann Lee’s visions informed four basic tenets: communal living, celibacy, regular confession of sins, and separation from the outside world. To rigorously follow these tenets meant that they could achieve perfection. Moreover, following these rules meant assurances of spiritual and physical equality; non-Christians and all races were welcome if they agreed to these four principles. The Shakers also believed in gender equality, even though their spheres of activity and responsibility were kept separate.”[52]

To make money for the community, the Shakers built furniture. Shaker furniture was rather austere, minimalist, based on function not form, with an emphasis on incredible craftsmanship.

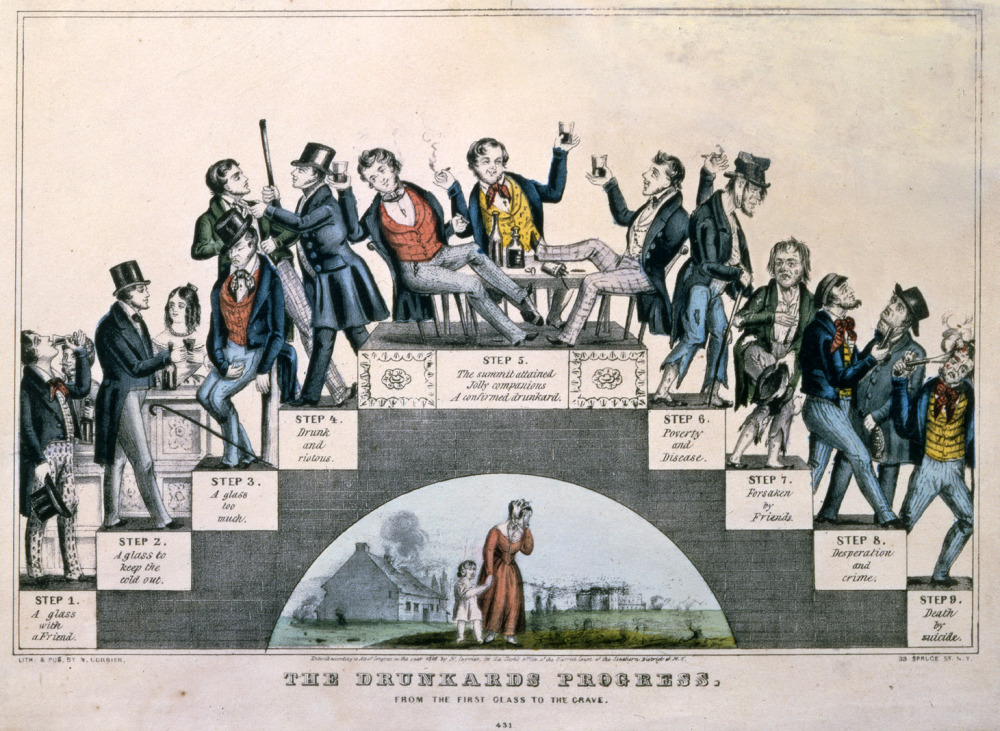

Temperance

Some white, middle to upper-class American-born white women saw immigrant culture as radically different, inferior (and threatening) to American culture and some went so far as to brand alcohol consumption as immoral. “These people feared that God would no longer bless the United States and that these ungodly and unscrupulous people posed a threat to America’s political system. To survive, the American republic, these people believed, needed virtuous citizens. Because of these concerns, many people became involved in reform movements during the early 1800s. One of the more prominent was the temperance movement. Temperance advocates encouraged their fellow Americans to reduce the amount of alcohol that they consumed. Ideally, Americans would forsake alcohol entirely, but most temperance advocates remained willing to settle for reduced consumption. The largest organization established to advocate temperance was the American Temperance Society. By the mid-1830s, more than 200,000 people belonged to this organization. The American Temperance Society published tracts and hired speakers to depict the negative effects of alcohol upon people.”[53]

The women who led this movement saw the overconsumption of alcohol as being a social, moral, and religious problem. While most sought to control the production and consumption of alcohol, a few, such as the well-known preacher Lyman Beecher (father to Elizabeth Beecher Stowe who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin) wanted to completely do away with alcohol. These reformers define temperance as prosperity plus godliness plus political freedom while intemperance is poverty, damnation, and tyranny. In the 1840s states allowed counties and even cities to decide for themselves the question of temperance, thus this country was a patchwork of varied consumption laws. While some towns tried to merely limit when alcohol could be served in public, other towns prohibited the complete consumption of alcohol. Maine was an anomaly. In 1851 the state legislature prohibited the consumption of alcohol statewide -known as going “dry”. Four years later the state repealed its prohibition on the consumption of alcohol.

“Temperance reform proved effective. After peaking in 1830 (at roughly five gallons per capita annually), alcohol consumption sharply declined by the 1840s (to under two.) The movement enjoyed some legal successes. By the mid-1850s, laws prohibiting its manufacture and sale other than for medicinal purposes had passed in New England, Ohio and Northwest Territory, New York, and Pennsylvania—legislation that foreshadowed national prohibition in the early twentieth century. Of course, not all who supported temperance reform advocated total abstention, and not all who supported voluntary abstinence supported the legislation of morality. And there were opponents of the organized movement who supported self-regulated temperate consumption. In addition, advocates of abstention did not necessarily adhere to what they preached, even on such public occasions as temperance conventions. It was not a black-and-white issue. As Christopher Columbus Baldwin, a young lawyer and later librarian of the American Antiquarian Society, explained in a diary entry, when the State Temperance Convention met in Worcester in 1833 some of the nearly five hundred delegates showed clear signs that they had not converted to the doctrine of abstinence that they professed. While he expressed pleasure at efforts to reform the besotting practices of drunkenness, he personally believed in moderation. Expressing the sentiments of many, he further observed:”

I am not a member of a temperance society, contenting myself with the practice of virtue without extra preaching it to others. It is one of the faults of the day to occupy so much of our time in recommending the practice of virtue that we have no time left us to perform it. So true it is that when mankind undertake a reformation they are always running into extremes.[54]

Physical Health (Diet)

Sylvester Graham (1794-1851) was the seventeenth child in his family. He became a Presbyterian minister and promoted a healthy eating regiment consisting of not eating meat, not drinking liquor, not smoking, exercising, and opposing sexual excess, including masturbation. He believed that healthy living was the key to healthy morals (no smoking, drinking, or masturbation). He also believed in such “scientific” practices as phrenology (determining one’s health and future by feeling the bumps on one’s head) and spiritualism (the practice of being able to summon and talk to the dead). He tried to develop what he believed to be the perfect food. This food was vegetarian, had to be easily transported, and did not need refrigeration and when eaten would cut down on one’s interest in the consumption of alcohol, smoking, and sex.

“The reverend’s sentiments may sound like the ravings of a mentally disturbed baker, but in 1837, A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making was a runaway hit. Graham was a star preacher within the temperance movement, and championed a strict, meat-free diet modeled after the Bible’s original vegetarians: Adam and Eve. Graham’s diet called for consuming only plants, water (no alcohol), and other “pure” items one might find in the Garden of Eden. Chief among Graham’s concerns was whole-grain bread, made from home-ground wheat, which he viewed as the cornerstone of modern, impure lifestyles. A Treatise on Bread and Bread-Making inspired the production of so-called graham flour, graham bread, and, most famously, graham crackers.”[55]

“Graham’s followers established boardinghouses in various cities across the country where Grahamites could stay and take their meals while traveling. They opened provisions stores to supply pure, healthy foodstuffs. They published a magazine, the Graham Journal of Health and Longevity, and numerous books; established physiological societies in cities like Boston and New York and on college campuses like Oberlin, Wesleyan, and Williams; and held a number of health conventions. By the Civil War, Graham’s tenets and theories had influenced even more-widespread health crusades, such as the water-cure movement, which used various water treatments to cure disease and maintain health, and phrenology, the pseudoscientific movement that attributed character traits and conducts to the physical shape and size of the skull. New religious movements like Christian Science and Seventh-day Adventism incorporated Grahamite principles. And following the Civil War, entrepreneurs like the cereal mavens and the Kellogg brothers integrated the Grahamites’ concerns into the marketing of their commercial products. The diet reform movement influenced many Americans who did not consider themselves Grahamites. Nineteenth-century manuscripts and published cookbooks included recipes for Graham bread, Protestant ministers offered sermons on the connection between diet and morality, and advice books urged healthy living based on Grahamite principles. In short, the ideas and values of the diet reform movement as initiated by Graham became part of mainstream American culture in the nineteenth century and beyond.”[56]

Urban Reform and the Working Men’s Party

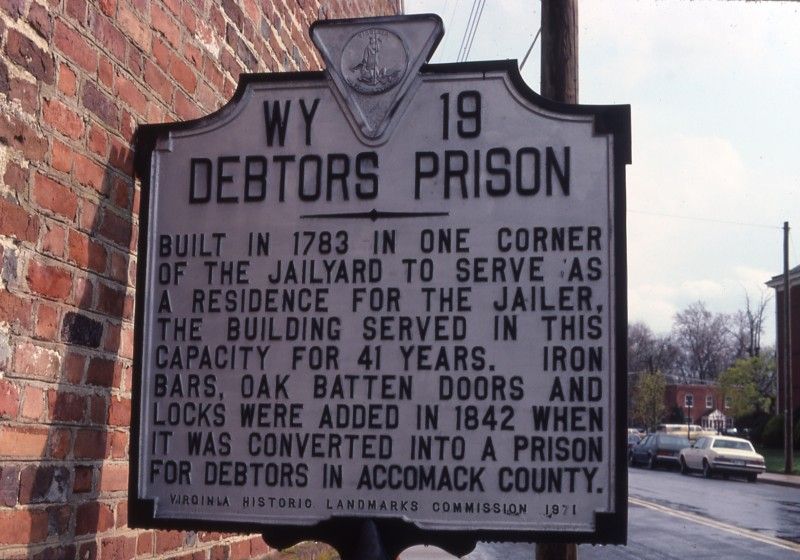

Some reformers focused their time and energy on alleviating poverty in the growing urban centers of the United States. They dealt with issues of labor, prisons, and the mentally ill. But not because they wanted to truly help these people (usually immigrants) transition to a better life, but because these reformers blamed poverty, illness, and illegal activities as examples of moral corruptness. In other words, people who were poor were poor because of choice not circumstance, and poverty was immoral. Other groups of urban reformers did indeed try to alleviate the conditions in urban centers that resulted in poverty and illness, such as the Working Men’s Party. This political party sought to get reformers elected to local positions such as town council members. This political party supported the ten-hour workday, abolish debtors’ prisons, and supported free, public schools. For example, these reformers believed that prisons should be a place to reform criminals into productive members of society, not a place to punish people. Thus, developed the first “reform schools.”

The following is from a Michigan State University history department’s digital history project.[57]

“The origin of the Working Men’s Party (Philadelphia) can be found in the Mechanic’s Union of Trade Associations, which was America’s “first union of all organized workmen in any city.” At its peak in 1828, The Mechanic’s Union was comprised of 15 trade societies. These societies were organized due to their common goal of achieving a ten-hour workday without having their wages reduced. Organizations within the Union, such as the Carpenter’s society, found it prudent to have political representation, therefore “political clubs” were established to endorse candidates for office, and to educate the workers on political issues.

“Man is by nature an active being. He is made to labor.” – Edward Everett

According to Edward Everett of the Working Men’s Party in Massachusetts, Men are constantly in a state of “want,” therefore he will work to maintain what he has or work harder to obtain what he desires. This philosophy somewhat mirrored that of the General Trades’ Union, which emerged after the collapse of the Working Men’s Party: Being in a constant state of wanting is selfish. However, unlike Trade Unionists, American labor parties focused more on their position in politics rather than their economic position.

In a contradictory statement, Everett claims that it was not the goal of the party to win positions in government:

“The next question, that presents itself, is, what is the general object of a working men’s party?” “To this I suppose I may safely answer, that it is not to carry this or that political election; not to elevate this or that candidate for office, but to promote the prosperity and welfare of working men.”

Everett’s quote also reveals the disconnect and contention between Working Men’s Parties from different states. In 1829, Thomas Skidmore, founder of the New York City Working Men’s Party, published his treatise The Rights of Man to Property. This document further illustrated the desires of the working man, but also exemplified the different ideologies within the same movement. In regards to land, Skidmore argued: “It should be recollected, that equal property being given to every human being as he arrives at the age of maturity, would necessarily cause equal education, instruction, or knowledge, or nearly so…” Skidmore professed that this redistribution, along with an elimination of wills, would make men more equal. He goes on to write, “Men starting equal in property and knowledge, could never have been cheated or forced into any such enormous injustice…”[58]

This reform impulse began to wane in the early 1850s as reformers’ attentions turned to more pressing, national issues such as the question of slavery.

Education Reform

Horace Mann is most associated with education reform. He was born in 1796 in Massachusetts. He became a Unitarian, who focused his energies on doing something to better humanity (big stuff). He graduated from Brown University and as a young man, he championed hospital reform but became the first Secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education in 1837 where he promoted public (meaning free) schools, teacher training colleges, and public libraries. All of which would be supported through state taxes. He believed that students could best learn from teachers who were classically educated on how to teach so in 1839 he established Massachusetts’ first teacher colleges, called the Normal School for Teachers. One of the first three of his Normal Schools was located in Bridgewater.

A Bridgewater student looked at Mann and his ideologies on education and gender. He wrote:

“Teaching and education had traditionally been considered men’s responsibilities however, Mann circumvented this tradition by promoting a particular form of education for women- that of normal schools, and a particular type of teaching- working with young children in common schools. Thus, Mann’s plan for improved common schools brought women outside the home without interfering with the traditional notions of women’s proper domain. Using the popular ideology of his time, Mann carved out a more public space for women without directly challenging the separate spheres ideology.”[59]

“Mann knew that the quality of rural schools had to be raised and that teaching was the key to that improvement. He also recognized that the corps of teachers for the new Common Schools were most likely to be women, and he argued forcefully (if, by contemporary standards, sometimes insultingly) for the recruitment of women into the ranks of teachers, often through the Normal Schools. These developments were all part of Mann’s driving determination to create a system of effective, secular, universal education in the United States.”[60]

“His influence soon spread beyond Massachusetts as more states took up the idea of universal schooling. Mann’s commitment to the Common School sprang from his belief that political stability and social harmony depended on education: a basic level of literacy and the inculcation of common public ideals. He declared, ‘Without undervaluing any other human agency, it may be safely affirmed that the Common School…may become the most effective and benignant of all forces of civilization.’ Mann believed that public schooling was central to good citizenship, democratic participation, and societal well-being. He observed, ‘A republican form of government, without intelligence in the people, must be, on a vast scale, what a mad-house, without superintendent or keepers, would be on a small one.’[61]

Mann was the first president of Antioch College. Antioch was this nation’s first public, nonsectarian, coeducational institution. Antioch was started by a fringe religious sect called the Christian Connection. One of Antioch’s graduates was Robert Owen, who established the Utopian society called New Harmony.

One of my students, Tin Tran, looked at education reform in Baltimore, Maryland in the mid-19th century. He discovered that there was a keen interest to develop a free education system in its largest city, Baltimore (called “Mobtown”) in order to keep younger people from falling into a life of crime, violence, and drunkenness.[62] However, the class of slavers was powerful, and only supported such educational opportunities for children from more well-to-do families. Certainly not children from poor families. Nonetheless, city reformers in Baltimore supported a fair education system and improvement in moral and industrious behavior for all young children.[63]

Pressure from the state political and economic leaders would eventually be ignored by Baltimore’s leaders because education would not be “an effective weapon in the fight against juvenile crime ”if it only reached the middle and upper class”[64] In 1828 Baltimore city officials created the Board of Commissioners of Public Schools to create and supervise a public school system. Those schools were nonsectarian but not coeducational. And, for white children only. The first school for Baltimore’s Black children will not open its doors until 1864 -the Colored School Number 1, which was co-educational.

The July 26, 1843 edition of The [Baltimore] Sun reported on the examinations of male and female students at Public Schools 1, 2, and 3 as the first order of business under Local Matters. Male and female students were tested, under the eyes of school commissioners, on the subjects of geography, arithmetic, English grammar, penmanship, and history. The paper went on to state:

“The satisfaction expressed by parents upon the decided improvement of their children is perhaps after all the best criterion of the success of the system; and the degree of satisfaction which prevails in this quarter, may be easily and unerringly inferred from the crowded state of all the schools, a vacant seat being rare to the eye, in any of them (The Sun 1843).[65]

Moral Reform – Dorothea Dix

Jails used to be a place where sadistic guards abused prisoners until they were released back into the community. In the early 19th century there was a movement away from punishment and towards reforming prisoners through training and education, especially on ethical behavior. These were the first “reform schools” that so many young boys were sent to after the Civil War until World War II.

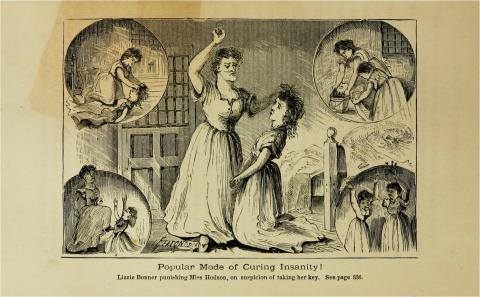

There was also an impulse to better treat mentally ill people. The creation of the first state asylums came into being, then reforms began to call for more humane treatment such as helping the mentally ill by training those who could learn to re-enter society. Eccentric behavior was seen at that time as mental illness thus so many people were institutionalized for having extreme personalities. “During the 19th century, mental health disorders were not recognized as treatable conditions. They were perceived as a sign of madness, warranting imprisonment in merciless conditions.”[66]

One of those reformers was Dorothea Dix. Born in 1802, at an early age she called for the creation of state hospitals to better treat the mentally ill than they would receive at home. Usually, those with mental illness were shunned by the family, sometimes chained to beds. She traveled throughout the country investigating the treatment of mentally ill people and then lobbied state legislatures to finance state-run mental hospitals. “‘I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience,’ wrote Dix in a Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts in 1843.”[67] This began in 1841 when she became a volunteer Sunday school teacher for female inmates in a jail in East Cambridge, Massachusetts and got a firsthand look at how people were treated who were suffering from mental illness. “They were chained to beds, starved, and abused – punished as if they were criminals.”[68]

“After touring prisons, workhouses, almshouses, and private homes to gather evidence of appalling abuses, she made her case for state-supported care. Ultimately, she not only helped establish five hospitals in America but also went to Europe where she successfully pleaded for human rights to Queen Victoria and the Pope.”[69]

During the Civil War, she became the superintendent of the Union Army Nursing corp. “At the start of the Civil War in 1861 Dix was inspired to aid the war effort. On April 19, when a Massachusetts regiment en route to Washington was attacked by a secessionist mob in Baltimore, Maryland, Dix immediately took action. She took a train to Baltimore intending to help care for the wounded but found improvised hospitals already providing aid. She then continued on to DC where, on the same day as the attack in Baltimore, she offered her services as a nurse at the War Department. Though she had no formal medical training or experience, Dix was made Superintendent of the United States Army Nurses on June 10. She quickly and adeptly acquired medical supplies and selected and trained nurses to administer to DC hospitals. Dix was a strict captain, requiring that all of her nurses be over thirty, plain looking, and wear dull uniforms. She earned a reputation for being firm and inflexible, but ran an efficient and effective corps of nurses.”[70] Her work to professionalize the nursing resulted in an increase in the survival rate of wounded soldiers.

One of her nurses, Cara Barton, established the American Red Cross after the War. Another well-known and respected nurse was Mary Ann Bickerdyke who helped create Army hospitals and was the head of the nursing corps under General Ulysses S. Grant. She was later attached to William Tecumseh Sherman and was a trusted adviser who ignored military protocol in pursuit of bringing better care to the sick and wounded Union soldiers. When an officer complained to General Sherman about Bickerdyke’s nontraditional approach, Sherman allegedly proclaimed that there was nothing he could do about her because “she outranks me.”

Sonia Ezeokwonna looked into Dix, and here’s what she found.

“It is the woman’s appropriate duty and a particular privilege to … implant in the juvenile breast the first seed of virtue, the love of God, and their country, with all the other virtues that shall prepare them to shine as statesmen, soldiers, philosophers, and Christians.”[71] That was a statement made by a remarkable woman of Nineteenth-century in her 1818 writing where she reminded women of their rights and duty to society. Those words were to challenge and propelled women to the right channel of Nineteenth-century reform. The reform gave raise to notable women in American history in which Dorothea Dix was one of them

Dorothea Dix was a Ninetieth-century activist and a social reformer. Dix was born in Hampden, Maine in 1802. She lived with her grandmother in Boston because of abuse from her alcoholic parents. Upon her return from Europe where she met with groups of reformers that cared for mentally ill patients, she started a reform in America. The reform addressed the view that a child with a disability or mental health condition was a sign from God that the person or the family was a bad creation. Dix said that the chaining and confining of disabled children till they die was immoral and that the State should take care of them, identify the ones that needed assistance for the rest of their life, and the ones that should be independent. The work of Dix to improve the treatment of persons with mental illness illustrates the gendered nature of Nineteenth-century reform activity.[72] Before the introduction of prison as a form of punishment, people were been punished physically by either flogging or killed by hanging or firing squad. Dix introduced moral reform in the prison; “prison should be a middle ground where individuals should be reformed not where they should be beaten. Dix’s passion for prison reform motivated her to write a powerful memorial which she presented to the Legislature of Massachusetts in January 1843. In her memorial, she highlighted the suffering humanity she observed in several prisons and almshouses she visited in the State. “I must confine myself to few examples but am ready to furnish other and more complete details if required.”[73] She concluded her memorial with “I commit to you this sacred cause. Your action upon this subject will affect the present and future condition of hundreds and thousands.”[74] Dix was not dissuaded by many politicians disagreeing with her, but she continued. She eventually established asylums in New Jersey, North Carolina, and Illinois.

Dorothea Dix worked as a nurse during the American civil war with the Union Army. She was known for treating both Confederate and Union soldiers, a practice that gained her respect from many. As of then, male doctors openly expressed disdain for female nurses, and Dix continued to push for formal training and more opportunities for women nurses.

After the war, Dix raised funds for the building of a national monument to honor deceased soldiers. She continued fighting for social reform throughout her life. Her work in support of better care for the mentally ill culminated in the restructuring of many hospitals both in the United States and abroad. She died on July 17, 1887, and was buried in Cambridge Massachusetts.[75]

The history of the American moral reform movement of Nineteenth-century would not be complete without mentioning the contribution of Dorothea Dix. She broke the jinx of women as a nurse and even brought reforms in prison and mental illness treatment.

Anti-Slavery/Abolitionists

In 1829, David Walker, an ex-slave, published a treatise called An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, in which he wrote:

“Americans, Oh Americans, I warn you to repent and reform, or you are ruined! …they want us for their slaves, and think nothing of murdering us. . . therefore, if there is an attempt made by us, kill or be killed. . . and believe this, that it is no more harm for you to kill a man who is trying to kill you, than it is for you to take a drink of water when thirsty.” Walker will be killed.

The following year Nat Turner led a short-lived rebellion in Virginia, compelling the Virginia legislative branch to dig in their heels passing a series of laws making slavery even more brutal and nasty, such as prohibiting manumission. Turner and his seventy-something followers killed around 65 white people. And while the revolt was put down, some 200 slaves were killed during the rebellion and in retribution, after Turner was captured. Southern leaders, such as Senator (and one-time vice president) John C. Calhoun began referring to slavery as “a positive good.” Calhoun argued that slaves were better treated than industrial workers in the North. In 1837, before the Senate, Calhoun talked about how the abolition and the Union could not exist in the same universe: “As the friend of the Union, I openly proclaim it, and the sooner it is known the better. The former may now be controlled, but in a short time it will be beyond the power of man to arrest the course of events.”

And three years later, in 1833, England abolished slavery. Each year thereafter England hosted an anti-slavery convention.

In 1840 several Americans traveled to England to attend the annual convention, including Lucretia Mott, Henry and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the Grimke sisters. The women were initially prohibited from entering the hall, being that the activities within were deemed inappropriate for the weaker sex. After some persuasion, the American ladies would be admitted after a partition was built so that the men on the floor would not be able to see the women. On the way back to the United States the group talked about ways they could help. One idea was that of the free store.

A free store was a store that sold goods made by people who freely worked, those not in bondage. The free store idea failed. People want cheap stuff. Nevertheless . . .

“The abolition of slavery represents one of the greatest moral achievements in history. As late as 1750, slavery was legal from Canada to the tip of Argentina. Each of the 13 American colonies permitted slavery, and before the Revolution, only one colony–Georgia–had sought to prohibit the institution. The governments of Britain, France, Denmark, Holland, Portugal, and Spain all openly participated in the slave trade, and no church discouraged its members from owning or trading in slaves. Yet within half a century, protests against slavery had become widespread. By 1804, every state north of Maryland and Delaware had either freed its slaves or adopted gradual emancipation schemes. In 1807, both the United States and Britain outlawed the Atlantic slave trade. When Congress prohibited the trans-Atlantic slave trade, there were grounds for believing that slavery was a declining institution. In 1784, the Continental Congress fell one vote short of passing a bill that would have excluded slavery forever from the trans-Appalachian West. In 1787, Congress did bar slavery from the Old Northwest, the region north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi. During the 1780s and 1790s, the number of slaves freed by their masters rose dramatically in the Upper South.”[76]

“At the present rate of progress, one religious leader predicted in 1791, within fifty years it will ‘be as shameful for a man to hold a Negro slave, as to be guilty of common robbery or theft.’ But when William Lloyd Garrison called for an immediate end to slavery in 1831, the grounds for optimism had evaporated. Despite the end of the Atlantic slave trade, the slave population in the United States had grown to 1.5 million in 1820 and over two million a decade later. The cotton kingdom had expanded into Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. In the North, free blacks faced increasingly harsh discrimination.”[77]

In the 1830s some viewed slavery as a sin and like all sins needed to be eliminated. There had been a history of dealing with slavery before the establishment of the US Constitution. The highlight of the Articles of Confederation was the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The Northwest Ordinance outlawed slavery in what was considered the northwest part of the United States -today consisting of states such as Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois. Slavery generally ended slowly in the North beginning in 1777 when Vermont abolished it. Manumission was one way that northern states ended slavery: people would set free their slaves in their will. Other states passed laws ending slavery once slaves reached a certain age or who were under a certain age. The US Constitution almost sidestepped slavery, never using the words “slave” or “slavery” but the document did note that people in “perpetual bondage” who escaped to free states or territories were not free, that runaway slaves could be returned to their owners, and that slaves counted as 3/5ths of a human being for population purposes in consideration of the number of members each state could send to the House of Representatives. Finally, the Constitution noted that the US would stop importing slaves by 1808.

Some reformers supported colonization. Freemen (slaves who were set free or Africans born into freedom) would be sent to Africa for land purchased by reformers. In 1817 the American Colonization Society secured land in the west coast of equatorial Africa and named it Liberia with its capital of Monrovia (after the sitting president at that time -James Monroe). A few later, the ACS began sending ex-slaves “back” to Africa. The ACS, like many northerners, believed that whites and blacks could not (or should not) live together, thus holding a rather pessimistic view of race relations. There would be two “back to Africa” movements, this time led by African Americans, in the twentieth century, by the way. By 1831, the ACS had only been able to repatriate about 1400 ex-slaves in part because the ASC did not have enough ships to transport the ex-slaves, they did not enough money to buy the slaves their freedom and pay to have them shipped to Africa, and, primarily, because most slaves by the 1820s were not from Africa and thus they had no intention of going to a land they did not know. One supporter or colonization was a young Abraham Lincoln who gave money to the American Colonization Society.

Slavery slumbered along until 1819 when Missouri applied for statehood. Missouri sought to enter the United States as a slave state, but the state was situated north of the Mason-Dixon line. The Mason-Dixon line was an area surveyed by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to settle disputes among states’ borders such as Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, to name a few. As time went on, states and territories north of that survey line ended slavery while states or territories south of the line supported slavery. James Tallmadge of New York proposed an amendment calling for the gradual emancipation of Missouri’s slaves: no more slaves could enter the state and all children of slaves would be freed.[78]