28 Saving Capitalism: The New Deal Era, 1933-1940

New Deal, 1933-1940

Jim Ross-Nazzal and Students

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt went to work to bring immediate relief, long-term recovery and to save capitalism. In the first 100 days, President Roosevelt helped create relief opportunities to include the CCC, FERA, AAA, TVA, NRA, PWA, and HOLA. Then there was a hold over from the Hover administration, the RFC.

The National Archives hosts an online display of CCC images entitled Spotlight: Photographs Documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The two images above come from that portal. Places where women received training were called She-She-She camps. These were the brainchild of Eleanor Roosevelt. The women’s camps never assisted anywhere near the number of women as the CCC camps helped men, but the She-She-She camps could be considered part of Roosevelt’s work towards gender equality and Civil Rights during the Great Depression.

A version of the CCC exists today. It’s called AmeriCorp.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration was led by Harry Hopkins. Between 1933 and 1935 his organization spent roughly $3 billion. FERA’s job (no pun intended) was to create unskilled jobs in state and federal government. One unique aspect of FERA was vocational education. FERA was partly segregated in the sense that there was a female administrator named Ellen Sullivan Woodward who directed work for women, such as clerical and secretarial.

Henry Wallace led the Agriculture Adjustment Administration (AAA) paid subsidies on hogs, dairy, wheat, corn and cotton in order to stabilize prices to the World War I era. The AAA did not succeed in its goal -massive need of food during World War II did, however. Subsidies are a part of farming life in America today. In fact, in 2019 the Trump administration paid farmers a subsidy to make up for their losses due to the tariff war with China.

Another work relief job program was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). There was a section of the American southeast (roughly eastern North Carolina to northern Alabama) that was exceptionally rural and without electricity. Ran by David Lilienthal, the project of building dams for flood control and electricity as well as fertilizer and navigation management for seven states and employed around 9,000 people.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) created the National Recovery Administration (NRA). Led by retired General Hugh S. Johnson, the NRA sought to bring together labor, industries and government to, in a nutshell, fix prices, to include a minimum wage.

“Johnson created ten codes dealing with the largest nation segments in industrial and commercial: steel, automobiles, lumber, coal, petroleum, textiles, garment making. building construction, wholesale trade, and retail trade.”[3]

The NRA was supposed to reduce competition, allow all businesses to make a profit while providing a livable wage for their employees and a fair-priced product for customers. The Supreme Court will find the NRA unconstitutional by a vote of 9-0. The mascot of the NRA was the blue eagle, which the NRA’s detractors called the sick chicken.

The NAACP called the NRA the Negro Removal Act because business owners who paid a minimum wage would fire black employees and replace them with white employees, thus raising the unemployment rate for African Americans.

One supporter of the NRA was a Philadelphia businessman named Burt Bell. In 1933, the National Football League gave Bell and the City of Brotherly Love an expansion team. Bell chose the Eagles as his new team’s name after his support for FDR, the NRA, and the Blue Eagle.

The Public Works Administration, lead by Harold Ickes, spent about $7 billion in building around 34,000 projects such as dams, bridges, ports, hospitals. court houses, airports and other public facilities. The Hoover Dam is a PWA project.

Harry Hopkins ran the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA hired many unskilled workers for unskilled jobs, such as teaching and nursing aids but also to build roads, dig ditches and lay pipes. However, the WPA also hired musicians, actors and director as well as painters/artists and writers. The Federal Writers’ Project will eventually locate thousands of ex-slaves and take their oral histories, which are available here.

The Home Owners’ Loan Act (HOLA) of 1933 allowed homeowners to keep their homes by “transferring” their mortgages from the bank or financial institution to the federal government under the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. The life of the note as extended to 15 years, thus lowering the monthly payment. Nevertheless some still fell behind and the government ended up foreclosing on hundreds of thousands of homes. But some aspect of HOLA was investment based -the federal government could not lose money in order to help as many people as possible. Thus, government officials determined which areas of cities were better and worse investment opportunities. Which areas were not likely to be good investments and those areas were marked in red. During the modern Civil Rights era (even beyond the Fair Housing Act f 1968) some banks would not give mortgages to people of color and landlords would bot rent to people of color outside of the “redlines.” Redlining became a way to instill racial segregation after the Great Depression. In the 1970s, Donald Trump had a history of racial bias in housing and was charged by the federal government for refusing to rent his apartments to people of color -years after such practices became against federal law. The parties came to a settlement.[4] Something along the lines of the HOLC exists today. As part of the G.I. Bill, the federal government guarantees mortgages in order for more veterans to secure mortgages without needing the best credit or the down payment. Congress will also pass legislation to save farms and businesses.

One of the first things Herbert Hoover tried was known as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The RFC loaned money to state governments, banks and big business such as railroads, which in turn would save banks and governments, modernize industries, launch public works projects and hire people, who would then be able to afford the stuff being produced. Problems with the RFC under Hoover was that there were possible instances of loans being made using political metrics, the first head of the RFC changed parties shortly after Hoover appointed him to lead the RFC, and the RFC was somewhat limited in scope and depth. Also known as Trickle Down economics. George H.W. Bush called it Voodoo Economics. Under FDR, the man selected to head the RFC was Mr. Houston -Jesse H. Jones, 1933-1939. Jones greatly expanded the RFC into every state, began buying gold to increase its value, loaned money to various businesses (the RFC under Hoover tended to limit loans to railroads) and creted its own finance company to loan money to home buyers -the Federal National Mortgage Association, also known as Fannie Mae. These and other measures made the RFC an important part of the New Deal.

My students looked at acts of Congress, federal organizations, and individuals under the New Deal. Here are some of their findings.

In May of 1933, Harry L. Hopkins became the first director of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. FERA took over Hoover’s Emergency Relief Administration.

Part of FERA was designated to help people find government jobs. Many times, local and state governments came up with school programs to give teachers jobs and even went as far as civil works projects.[5] People without the ability to work received help, and cash relief programs were aimed to help people that were unemployed with direct benefits; like food, shelter or money.[6] This is important because it translates into today with the daily option that some individuals still have to acquire food stamps and unemployment checks. It is also important because, with millions of people out of jobs, spending across the nation decreased and led to more unemployment; therefore, with more money put into the economy, the government was able to create more jobs.

The Federal Emergency Relief Act established a Rural Relief Program, or Rural Rehabilitation Division, that distributed funds into rural sectors.

The Rural Relief Programs’ main purpose was to rehabilitate low-income families and establish those families in rural relief camps. The idea was, families that were affected by the economic downfall would stay inside the camps until their financial circumstances improved. By 1935, states needed additional funds so FERA approved non-profit organizations known as rural rehabilitation corporations. Forty-five corporations were formed that same year. Established throughout the United States, each corporation was designated to improve the rural relief program. In order to improve the rural relief program, corporations purchased acre plots and later loaned these plots to families in the relief camps. Each corporation had its requirements on what could be constructed on the plots and how payments were going to be managed.

For instance, Texas allowed their families to build four-bedroom houses with indoor plumbing and could acquire the plot with no down payment.[7] In short, the Rural Relief Program managed to assist agrarian families in the economic downfall. Initially, FERA would provide payments directly to the poor, which aided the unemployed individuals as quickly as possible. However, the process seemed very degrading in many ways.

Although they started with direct payments of cash and kindness for those unemployed individuals, FERA’s funds increasingly went to work relief projects which would hire the unemployed for projects such as constructing roads and buildings and sometimes hired middle-class professionals as well.[8]

FERA also took over projects started by the Civil Works Administration in the winter of 1933-1934 when the CWA was terminated. Work relief programs, such as the Work Progress Administration (WPA) began in 1935, and was created under the auspices of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act.

The WPA paid for both projects and workers, but as much as possible was supposed to go into wages. By December, the WPA employed millions of workers, paying them wages that were higher than a direct relief assistant. The WPA continued to expand the variety of projects, building the nation’s infrastructure, and in the end achieved far beyond its expectations in employment of construction projects and work relief for manual workers.[9] The WPA agency was also able to launch more programs for artists, actors, authors, etc.[10]

The WPA employed about 600,000 Texans to build a myriad of projects, such as Dealey Plaza in Dallas where President Kennedy was shot in 1963.[11] In Houston, some of those projects included the creation of De Pelchin Faith Home and Children’s Bureau, development of Memorial Park, and landscaping and other improvements on the University of Houston campus.[12]

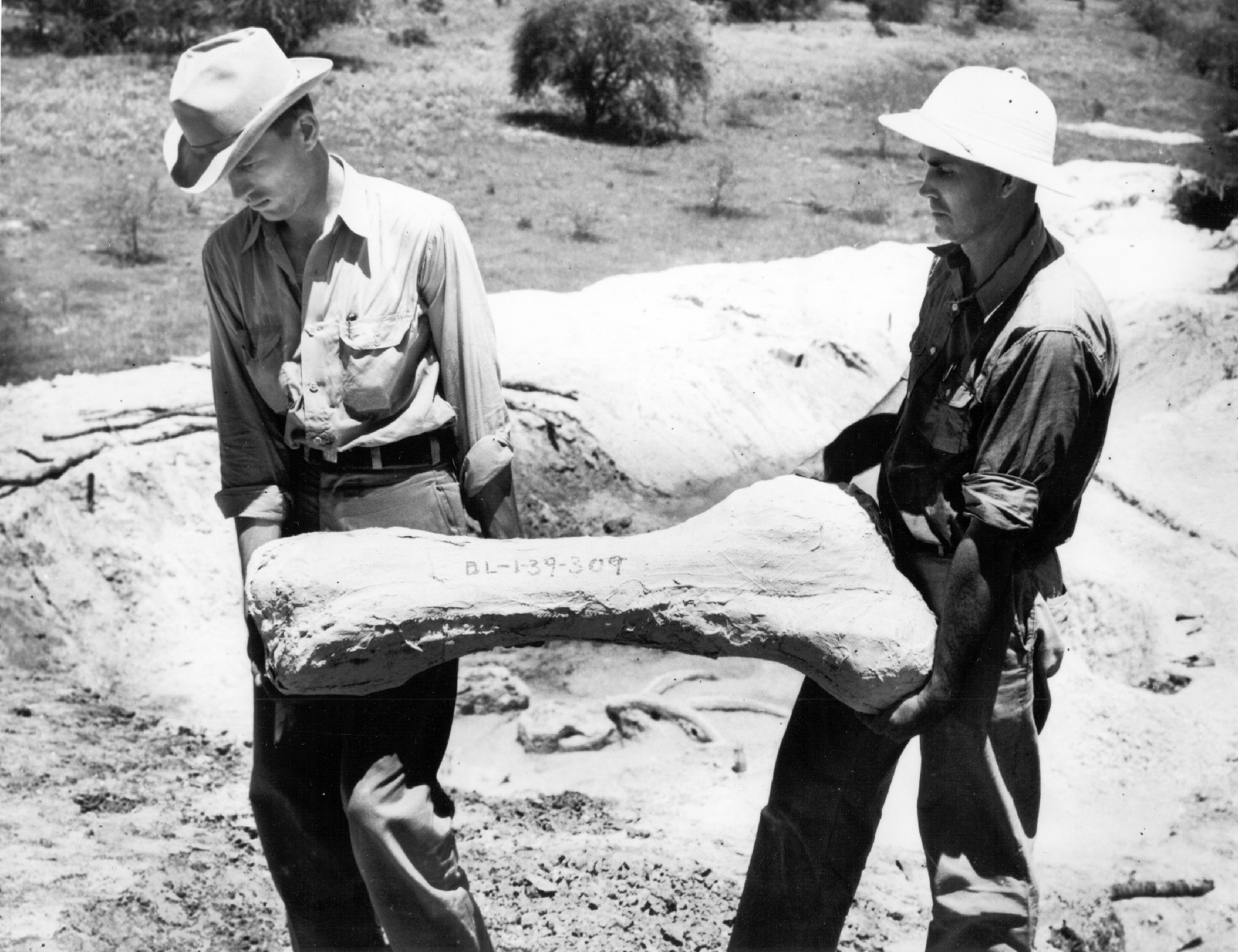

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of the main programs that President Franklin Roosevelt created to attempt to stabilize the economy during the 1930’s. The CCC conserved and amplified the natural beauty of America. The program was a main staple to the rise of otherwise down falling communities. This section will discuss how the CCC affected the American society and peoples.[13] The program would look out for natural resources and create jobs. Roosevelt finalized the details which included who would be eligible to work for the program: young, single, males who would spend some of their wages in the local community.

Roosevelt decided the program would employ men between the ages of 18 to 25. Although there was an exception to the age rule up to 27: in May of 1933, Roosevelt approved the enrollment of approximately 25,000 veterans from the Spanish American War and WWI.[14] Roosevelt only wanted to employ 500,000 in the beginning– he probably didn’t realize what great success the program would be, but as the need for jobs and the type of work to be done was great, the number of enrollees throughout the years increased dramatically. The CCC ended up employing over 3 million men from 1933 to 1942.[15]

Men would qualify only if their family was on some sort of government assistance and they would only be employed up to eighteen months.[16]

Enrollees, which is what young men working for the CCC were called, were to live in wooden barracks and given only two employee uniforms.[17] African American enrollees were segregated from their Caucasian counterparts.[18] Camp tenants were identified by placing a letter at the end of the camp name. For example, an African American camp would be “Company 410-C,” the “C” standing for “colored,” and a Caucasian camp would be “Company 411-W,” with the “W” standing for white.[19] The camps would house anywhere from 150 to 200 men.[20] These young men had to be willing to send money home, sometimes as much as $25 of their $30 back home to their families.[21] Besides a paycheck, the CCC provided employees with nourishment, attire, medical care, and educational opportunities, such as education.[22]

Education was provided to enrollees once they were off duties and it was not mandatory. They were able to gain knowledge and skills that would make them more employable once their time with the conservation program was complete. The benefits provided by the CCC commenced with the first camp opening, Camp Roosevelt.

In late April of 1933, a young man named John Ripley climbed a pine tree at the George Washington National Forest. Ripley, only tied by a rope, began chopping branch by branch until he made it back to the bottom and the pine was completely bare of any branches. As soon as Ripley tied the rope to the American flag, his peers, who were all wearing identical olive-green uniforms, began pulling the flag upwards onto the tree. Film crews, magazine photographers, and newspaper reporters all witnessed this event.[23]

The Camp Roosevelt event was a glimpse as to what the CCC was going to be working towards, the modification of natural landscape. In the nine years the CCC was active the enrollees planted 2 billion trees, slowed oil erosion on 40 million acres of farmland, and developed 800 new state parks.[24]

The CCC provided many young men who needed the work with the opportunity to help their family by providing a place where they knew income would be continuous so long as they remained enrolled in the program. Since the CCC only allowed select men to work, the unemployed population and economic crisis still existed. The need for economic security drove some men to great lengths to try and receive compensation for an idea they did not originate.

Two people wanting credit for the idea of the CCC were Joseph D Wilson of Atlanta and Major Julius Hochfelder, from New York. Wilson, a 36-year-old unemployed electrician and father of two, began writing letters to President Roosevelt constantly claiming that he was the originator of the idea for the CCC.[25] When he finally received a response he was upset that the letter stated the president was the person who originated the idea for the CCC and not him, Wilson took it upon himself to travel to the White House to personally confront Roosevelt. While there, he was denied entry to the executive room Wilson became enraged and retrieved a knife from his pocket and attempted to take his own life.[26] He was not successful in his attempt.

Hochfelder demanded a position with the CCC in exchange for him coming up with the idea of the program. He made his demands in the many letters written to the CCC headquarters.[27] Hochfelder had supporters who also wrote in wanting Hochfelder to receive what they believed was rightful compensation. Fechner decided to respond to a supporter of Hochfelder and explained, “We have letters from a large number of individuals…who feel they first conceived the idea of the organization. I merely point out these things so that you may know that Major Hochfelder is not alone in thinking he was entitled to some reward for suggesting the CCC plan to the president.”[28]

The CCC did not only affect the American people, but it also affected the conservation movement itself. The enactment of the CCC split conservation movement into two groups, the conservationists and the preservationists.[29]

The best example to use in explaining the views from the conservationists and the preservationists is Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the U.S. Forest Service and a conservationist, wanted the valley to be dammed in order to provide water for San Francisco.[30] John Muir, a nature writer and founder of the Sierra Club – an environmental organization, opposed the damming of the valley and insisted on the preservation of Hetch Hetchy Valley as “an aesthetic and spiritual resource” for the public.[31]. The dam was built and the first water reached San Francisco in 1934.

The Civilian Conservation Corps affected many different aspects of America. The program helped unemployed families gain some economic stability while also teaching those enrolled, through education, how to become a more appealing candidate for employment. While the CCC was supposed to be non-discriminatory, the segregation of races was still very much present, akin to the segregation of the US military. Despite this segregation, the program’s enrollees largely contributed to the conservation and preservation of American landscape. The program was very successful during the time it operated and helped America and American citizens improve.[32]

Amanda Peters, in the Fall of 2019, looked at Harold Ickes.

Harold L. Ickes was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most important allies. Ickes was a former newspaper reporter from Chicago turned bulldog politician.[33] Ickes actively campaigned for Roosevelt in the Midwest.[34] Ickes, living in Chicago as the time, was summoned to Washington to meet with Roosevelt.[35]

The President believed the two of them spoke the same language and asked that he accept the position as Secretary of Interior, which was a position Ickes would honor for thirteen years.[36] He was known to be honest, fearless, tough, and a little bit shrewd; he was just the person the President was looking for to join his cabinet.[37] He would later go on to earn the nickname “Honest Harold.”[38]

While the unemployment rate had dipped, thanks to Roosevelt’s tireless attempts such as the CCC, vast amounts of citizens remained out of work. Responding to the continuous problem, the Public Work Administration program was created to put unemployed men and women to work on projects designed and proposed by local governments.[39] Harold L. Ickes was named the head of that program.[40] The Public Work Administration provided grants-in-aid to local governments for large infrastructure projects, such as bridges tunnels, schoolhouses, and libraries.[41]

The program completed over thirty-four thousand projects, including the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel in New York.[42] The plans put millions of Americans to work. For the first time in years, people had hope.

The Great Depression did not end during Roosevelt’s first one hundred days in office, but numerous efforts were executed to aid in economic hardship. With robust allies, including Harold L. Ickes, Americans were starting to put their trust back into the government. Ickes was one of Franklin D Roosevelt’s greatest advocates who believed in his vision and devoted his career to the relief of the American people.

Frances Perkins did not just up on the scene when FDR plucked her from seemingly obscurity to become his Secretary of Labor and the first woman Cabinet member. Perkins lived a rich life as a labor leader and equal rights activist. This section looks as Perkins’s life before and during her tenure as Secretary of Labor and some students contributed context to include Rocio Joya, Debrework Tassew, and Joel Flores (and me, too).

During the time of the Great Depression women were faced with even more challenges. They were treated unfairly in the society and held to a much lower standard. Females were only meant to take care of the household and the family. It was extraordinary to demand higher regards. “But girls would not study physics: it was ‘unfeminine.’”[44] Predictably the situations where all the same for Frances Perkins. “But her gender and her identity as a middle-class “social worker” also caused organized labor, the press, congress and even some of her colleagues in the Roosevelt administration to judge her unfairly.”[45][46]

Despite the life style that most women were faced with during this time; she decided to be different and speak up her own perspective. She often referred to her self as revolutionist since the ideas she was proposing were not only ahead of their time but also coming from a woman. But she did not let it stop her, “feminism means revolution and I am a revolutionist.”[47] She was determined to make a change. “ Perkins became the impetus while FDR understood the need, and together they had the political skill to propose and shepherd legislation to successful outcomes.”[48] Perkins became the driving force behind the reconstruction of a better America. “Perkins was ever mindful that she was a direct descendant of Revolutionary War patriot James Otis, who had railed against taxation without representation.”[49][50]

Frances Perkins determination and hard work was undeniably manifested despite her gender. “In April 1910, Perkins became Secretary of the Consumers’ League of New York City, a position which involved investigating and reporting on the working conditions in the women-dominated industries.”[51] She was the first women in history to take on this role. “Gov. Franklin Delano Roosevelt named her (1929) industrial commissioner of New York state to direct the enforcement of factory and labor laws.”[52] This gave her the upper had in making crucial decisions that would help in creating more stable working condition.

In Honoring the Achievements of FDR’s Secretary of Labor, author Jessica Breitman mentions the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911 as the incident that initiated the working relationship between Perkins and FDR. “As a result of poor safety regulations, such as faulty fire escapes and locked doors, the workers could not escape the scorching fire… 146 workers died that day.”[53] Frances Perkins almost immediately took action and with the recommendation of ex-President Teddy Roosevelt Perkins created a “legislative panel that investigated factories and other workplaces and made sure they were up to code.” [54] “Frances Perkins,” Roosevelt said, “you can’t fail.”[55] Of course there was a nearly-equally long relationship between Perkins and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. As governor of New York, Perkins served him and the state in the same role as she would as his Secretary of Labor.

President Roosevelt selected Perkins to be his Secretary of Labor in part because of their long history together. Under her watch, she reorganized the Labor Department, got rid of old Hoover era cronies, and talked FDR into launching a public works program: “Unemployment is the pressing present issue,” she reported to FDR. “The first thing I think we should do, and this should emanate from the Secretary of Labor’s Office, although it’s a general problem, is to find some way of general relief and to do public works . . . They should be thought of as temporary. There are plenty of public works in different parts of the country, and we’ll have to devise a fiscal arrangement whereby the federal government can assist the states.”[56] In other words, Perkins was the impetus for Roosevelt’s work relief programs in general and the CCC, for example, in particular.

Before Perkins would agree to take the Labor job, she present FDR with a list of requirements to include a national minimum wage and some form of old-age pension. “About 44 million people collected Social Security checks each month; millions received unemployment and worker’s compensation or the minimum wage; others got to go home after an eight-hour day.”[57]. Among her accomplishments during her retirement from federal service was penning an autobiographical look at her relationship with FDR, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946). “When Frances Perkins first met Franklin D. Roosevelt at a dance in 1910, she was a young social worker and he was an attractive young man making a modest debut in state politics. Over the next thirty-five years, she watched his career unfold, becoming both a close family friend and a trusted political associate whose tenure as secretary of labor spanned his entire administration.” From the publisher.[58]

Appointed to lead the Department of labor in 1933, Secretary Perkins sponsored the Public Construction Projects program to provide employment to blacks; this program set aid aside specifically to hire blacks.[59] Furthermore, she testified to Congress on the importance of the passage of President Roosevelt’s plan to form the Civilian Conservation Corps and put America’s young unemployed men to work.[60] During the nine-years of the Corps existence it had employed at least 200,000 black workers and 87 percent of which participated in education programs that helped open the door to higher skilled jobs.[61][62]

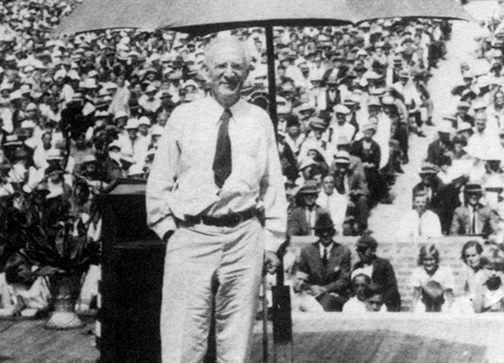

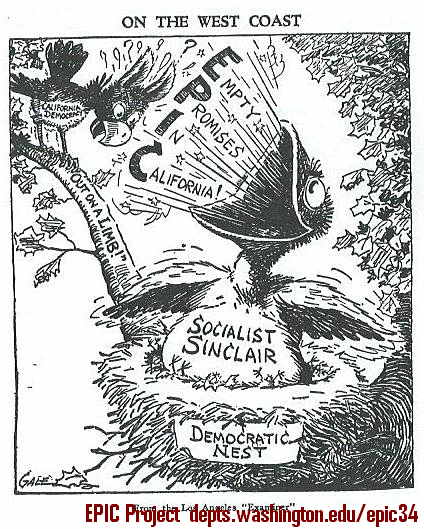

Iqra Yamin, an online student from the Spring of 2019, looked at Upton Sinclair.

Upton Sinclair had written dozens of influential books and became a famous leftist before running twice for governor of California as a socialist. He was encouraged to run again as a Democrat, with a plan based on ideas of his early writings.

“End Poverty in California (EPIC)” was a “production-for-use” plan that was meant to help the unemployed, the elderly, and the poor. Sinclair’s campaign built its structure upon the flaws of the New Deal, a plan made by Roosevelt. Although he supported it initially, put into effect, promises such as social security and repayment plans were forgotten, and Sinclair felt that the New Deal did not go far enough. He proposed that the unemployed work in unused farms and factories, which could be seized by the state from any property where the property taxes continue to be unpaid.[63]

EPIC was quickly adopted by the followers of his novel, “The Jungle”, and thousands of supporters to the plan followed on as well. Sinclair’s pamphlet, I, Governor, became the bestselling book right before he won the Democratic primary by a landslide. Sinclair’s impact on California did not go unnoticed, and a few days after the primary, he met with President Roosevelt. Although Roosevelt did not publicly endorse EPIC, he admitted that the framework of the New Deal could be “experimented” with.[64]

Sinclair’s opponent, Frank Merriam, was an unpopular Republican who used dirty tactics, such as receiving funding off the books, in order to protect his seat as governor.[65] The result was ninety-eight percent of newspapers opposing him, and almost six million pamphlets and two hundred thousand billboards taking his words out of context to paint him as a communist menace. While Roosevelt waited quietly, Sinclair fell in the polls, and the president was advised to not endorse him. Roosevelt’s political advisor, saw to it that Merriam would later support the New Deal, in exchange for continued silence of the White House in terms of his unfair campaign.[66]

Although Sinclair lost, the movement was already in place, and twenty EPIC supporting candidates won into state legislature. In 1934, Harry Hopkins revealed a similar plan, “End Poverty in America.” Coupled along with, EPIC largely pushed the New Deal left, focusing on legislation for public works and Social Security. Combined with the Works Progress Administration and National Labor Relations Act, the New Deal was turned into “The Second New Deal”, which was more anti business and pro-labor.[67]

The Second New Deal resulted in the Social Security Act, pension funds towards retired people, unemployment insurance, and many other acts and programs. Most of these are still in use today, under one form or another. The progress brought on by the New Deal and Second New Deal was seen as a growth in national strength, by economists and historians. Sinclair undoubtedly left an impact on the acts and policies of America, which lasted for decades and still exist today.[68]

This essay looks at a few aspects of the New Deal and the West (broadly defined as the Southwest and High Plains, but not the West Coast) .[69]

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/dustbowl-56a48c8a3df78cf77282ef0b.jpg)

American farmers became drought-stricken by the Dust Bowl which forced them out of their homes and lands in the Southwest and High Plains. President Franklin D. Roosevelt began by initiating New Deal programs that would occur immediately after the inauguration of the first Hundred Days that aimed at relief, recovery, and reform known as the 3 R’s.

One of the first relief programs president Franklin D. Roosevelt issued was the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA). With Harry L. Hopkins as the director, the Federal Emergency Relief Act was set in place to help unemployment by granting 3 billion to the states for direct dole payments or preferably for wages on work projects. Under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, in effect from 1933 to 1935, states were expected to contribute a fair share to a federal dole; if they did not, FERA Director Hopkins could cut off funds or even assume complete control over relief administration funds. This apparatus inevitably invited trouble throughout the nation, especially where recalcitrant governors attempted to use federal money to advance their political fortunes. But the conflict seemed to be especially intense in the West.[70] Fighting between Hopkins and Governors Edwing Johnson of Colorado and C. Ben Ross of Idaho destroyed chances of efficient relief administration in these two states.[71]

In the early 1930s, there were recurrent severe droughts going on in the Great Plains. Throughout Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and the Dakotas, high winds stirred the arid soil, loosened after years of rapid homesteading and commercial agriculture. Hundreds of dust storms ripped across the southern plains during 1933, a prelude to the major storm of May 1934, which whipped an estimated 350 million tons of earth into the sky.[72] Leaving farmers struggling with unstable farming practices, crops were killed off leaving them with no product to sell. Not only did it affected the crops, but the dust also suffocated livestock leaving farmers with very little resources.

American farmers were hit hard by the economic downturn in the 1930s. They not only had to deal with the depression but also, plummeting prices in crops, unpaid debt, and soil erosion.[73] On May 1st, Franklin Roosevelt established the Resettlement Administration which relocated urban and rural families, such as those affected by Dust Storm, to government made communities. Roosevelt appointed Rexford Tugwell as head of the Resettlement Administration. Tugwell was a part of Roosevelt’s first “Brain Trust”, a group of Columbia University academics that helped create policy recommendations leading up to the New Deal. During the two years the RA was active, it engaged in a variety of activities. One of them was financial aid and emergency loans which helped farming families that were in debt. The second project was conservation, planting trees on acreage which created a lot of miles of fire break and streams. Also educating farmers in best practices for land use. The RA built many model farm communities known as green belts around the country that housed many farm families.

Due to the crisis affecting Americans, President Roosevelt and Hugh Bennet prioritize putting a plan to help put a natural resource conservation act in place, The Soil Conservation Act. Bennet became known as “the Father of Soil Conservation” due to his influence on wanting to stop soil erosion. He would often discuss the warnings on not doing anything to stop soil conservation and how it would lead to the increase of abandoned farmland. It would take a number of years for the nation to heed Bennett’s warning but, with the New Deal, the federal government acted decisively. With funds from the newly-passed National Industrial Recovery Act, a Soil Erosion Service (SES) was created in 1933, with Hugh Bennett in charge.[74] It became another one of Roosevelt’s actions to help the country, specifically farmland and farmers to get back to their feet. The ambitious act established the Soil Conservation Service to combat soil erosion and “to preserve natural resources, control floods, prevent impairment of reservoirs, and maintain the navigability of rivers and harbors, protect public health, public lands and relieve unemployment.”[75] A year later, Congress awarded farmers that made efforts in planting grass and other things to help support the soil, leaving farmers being able to start over and plant crops.

Overproduction of crops and farm products was still a problem during the early 1930’s; the government in turn established the first Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 to increase farmers incomes to parity level by reducing overproduction. Parity pay was a benefit payment given to farmers to slowly increase prices to those seen during the pre-war and pre-depression period. The AAA addressed overproduction by paying farmers to reduce crop acreage. Reduction in crop acreage was later disestablished after the drought of 1934 causing the Supreme Court to declare the AAA unconstitutional in 1936. The first AAA caused unemployment to rise contradictory to why New Deal agencies were established.[76] To help farmers, after the first AAA was declared unconstitutional, New Deal agencies were still implemented such as the Soil Conservation Act and Domestic Allotment Act of 1936 These agencies focused on conservation by having farmers not cultivate their land, or farm specific crops such as soybeans, and realizing the need of large crop reserves.[77] The benefit payments were there to provide income and machinery needed for production. But in order for products to meet parity level balance between production and consumption of agricultural products had to be maintained.[78] Therefore, with a bigger focus on conservation and developing large crop reserves the second AAA was formed in 1938.[79] It was seen that between 1933-1939 higher expenditures were made to western states through all the New Deal farm related agencies.[80] Although prices were still not at parity level between 1933-1939, income did increase substantially with the second AAA and other New Deal farm agencies.[81]

The West has always been the place in US History where new ideas are put in motion, since the start of the Manifest Destiny. However, post- Great Depression, the West became very divided, due to the fact that for such a long time the West had an ideology of self-helped and hostility to governmental interference. Very Jeffersonian. This all changed when the New Deal (1933-1940) was set in motion by president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Most of the West was in dire need of employment, allowing president Roosevelt to set in place programs like FERA, CCC, AAA, Resettlement Administration, Soil Conservation Service and many more. Through this president Roosevelt brought the 3R’s: relief, recovery, and reform, helping the West economically and getting rid of the “Jeffersonian” notion.

This essay looks at the PWA through the lens of Native American History. Interesting stuff![82]

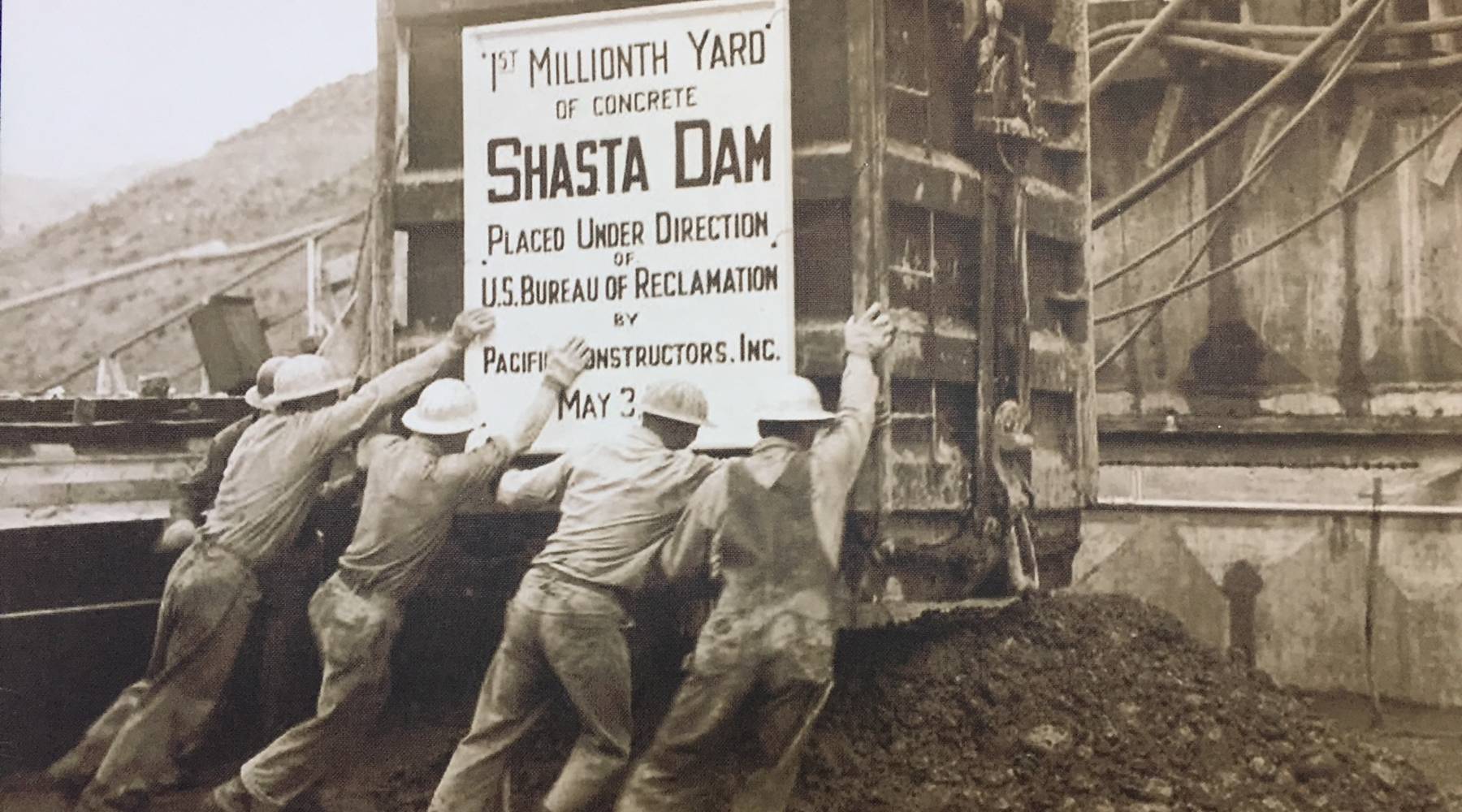

As the United States’ economy was declining during the Great Depression, unemployment was at its highest. US Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins proposed the idea of what became the Public Works Administration (PWA), and in response, the National Industry Recovery Act of 1933 created the PWA, led by Harold Ickes, which focused on building large-scale public works projects to improve employment and revive the economy, however, some of those efforts had unforeseen consequences. This essay will examine the effect that the Shasta Dam and Hoover Dam projects of the PWA had on Native Americans.

Transferred to the federal Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) as a public works project for the PWA because the state of California could not afford to fund it, the Shasta Dam (built from 1938-1945) is a concrete arch-gravity dam across the Sacramento River in Northern California.[83] The Shasta Dam had directly affected Winnemem Wintu tribe because it destroyed part of their land (homeland, tribal, and burial sites). The Central Valley Project had put pressure on U.S. Indian policy because a study from Redding Record-Searchlight revealed that northern California would be faced “with a power shortage in 1934 unless new plants [were] brought into production.”[84] This left Native Americans with less time for negotiating, especially for allottees who were hard to locate. As a result, the U.S Indian policy led to the dispossession of about 175 heirs and allottees.[85] In the first Indian allotment sale, Roy Nash, superintendent of the Sacramento Indian Agency, told Jimmie Mitchell, a Wintu, that “[t]his land would be flooded when the Shasta Dam is completed, and if sale is not made, it will be condemned,” which shows how strict negotiations were with the U.S. government.[86] In addition, burial sites that could not be found or were not near the twenty-six designated cemeteries recorded by the BOR, were to be left behind. One Wintu said, “it was against all Christian ethics to move them,” as government officials had laid the Wintu’s ancestors’ graves to higher ground, yet now spiritual sites and homelands are under water due to the Shasta Reservoir.[87]

The Wintu tribe were also unequally compensated for the land property taken by the government because some landowners could have been offered anywhere from ten to fifty dollars per acre, depending on the type of land. Winnemem Wintu Spiritual Leader and elder, Caleen Sisk-Franco, mentioned that most Wintu landowners were offered around “thirty-five dollars per acre for their allotments.”[88] In addition, property loss did not take into account of those who were not offered allotments, and ceremonial sites hold cultural, spiritual, and social value that could not be purchased. The problem was that the Central Value Project Lands Acquisition Act had “superseded all regulations and procedures that had previously applied to negotiations for the purchase of Native land allotments within the CVP area,” and it was vaguely worded which gave Ickes discretion over the amount of compensation and on fund use.[89] On the other hand, the Hoover Dam had affected Native Americans differently than the Shasta Dam.

The Hoover Dam, located on the Colorado River and near Boulder City, Nevada, had indirectly affected the Navajo tribe because a stock reduction (forcing the Navajo to reduce or sell their own animals) was implemented by the Federal government in 1934 which declined the Navajos’ economy. The U.S Soil Conservation Service had believed that silt (from the San Juan and Little Colorado tributaries of the Colorado River) was coming from the Navajo Reservation, which was a threat to Hoover Dam because the silt was causing land erosion on the reservation. The Federal government believed that overgrazing was the main cause of land erosion, despite the fact that the government had “misunderstood the erosion cycle and its causes… [the government blamed the erosion] largely on Navajo lands.”[90] As a solution to save Hoover Dam, the Federal government decided to place a stock reduction on the Navajo Reservation which forced them to sell and reduce the number of sheep and goats. The Federal government thought that the Navajo could meet wool and meat production with fewer animals, and that horticulture (agriculture of plants), in place of stock raising, could sustain the Navajos’ economic system.

Consequently, the assumptions of the Federal government would greatly affect the Navajos’ economy, especially among poor Navajos. When the Bureau of Indians Affairs, led by commissioner John Collier, realized that the Navajo had to sell their cull to make up for loss profit for the sheep purchase, about 148,344 goats were then targeted in the second stock reduction. The second stock reduction mostly affected poor Navajos because they had smaller herds which consisted of goats mostly because poor Navajos couldn’t afford sheep, unlike wealthier Navajos who could; the cost of living of the Navajo was also raised by 20 percent.[91] Peter Price, a Navajo who believed that goats were not meant to be marketed, told senators in a hearing that goats provide milk and meat to his children, and survived the winter better than sheep which shows that goats were a subsistence animal and held “practically no market value except among the Indians.”[92] Even though the Navajo did receive compensation for the stock reduction (about 1 million to 449,000 sheep units), sheep and goats held more value than cash could offer, and some Navajos had to leave the reservation to find work.[93] To show the mistrust formed by the stock reduction, the Navajos had rejected the building of a constitutional form of government proposed by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934–the IRA had promised to improve Indian economic life but had little influence on the Navajos’ economy.[94] Therefore, one can argue that leaders like John Collier were doing little to help the Navajos economy and was more concerned about the safety of Hoover Dam.

While the building of the Shasta Dam had directly affected the lands of the Winnemem Wintu tribe, the Hoover Dam, in contrast, had damaged the Navajos’ economy by the Federal government forcing the Navajo to kill and sell their own sheep and goats. Even though laws like the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 were meant to improve Native Americans lives during the New Deal era, Native Americans were still misrepresented by the U.S. government and some might continue to face problems with future changes of dams.[95]

I would like to thank Samuel Brown, Daniel Diaz, Vanessa Garza, Andrea Gonzalez, Glenda Gonzalez, Ashley Nandlal, Kim Nguyen, Adam Obregon, Nidia Perez, Guadalupe Rangel, Faith-Doris Olweny, Amanda Peters, Debrework Tassew, Christina Wagner, Iqra Yamin, James Frazier, Leonel Lizalde, Alejandra Lopez, Tatyana Marquez, Damian Mendez, Paulina Mosqueda, Christopher Alejo, David Arriaga, Snethia Bell, Le’azha Booker, Carolina Camacho Torres, Angelica Castillo, Raul Castillo, Alvaro Covarrubias, Adrian Deleon, Ly Do and Bria Fuller.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/520 Last accessed 10 MAR 2020 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hugh Johnson (1881-1942).” Faith Olney from Living New Deal, https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/hugh-johnson-1881-1942/ ↵

- https://www.politico.com/blogs/under-the-radar/2017/02/trump-fbi-files-discrimination-case-235067 ↵

- “Federal Emergency Relief Act (1933).” Living New Deal. Accessed December 3, 2019. https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/federal-emergency-relief-administration-fera-1933-19 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “A Brief History.” National Association of Rural Rehabilitation Corporations, https://www.ruralrehab.org/briefhistory.html ↵

- "Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA)." The Great Depression and World War II, Third Edition. Facts On File, 2017. Accessed December 8, 2019. https://online.infobase.com/HRC/Search/Details/2?articleId=194237&q=FERA ↵

- "Works Progress Administration (WPA)." The Great Depression and World War II, Third Edition. Facts On File, 2017. Accessed December 8, 2019. https://online.infobase.com/HRC/Search/Details/2?articleId=196452&q=wp ↵

- Angelica Castillo, Raul Castillo, Alvaro Covarrubias, Adrian Deleon, Ly Do and Bria Fuller provided this content (Fall 2019). ↵

- https://www.tsl.texas.gov/outofthestacks/tag/works-progress-administration/ ↵

- https://livingnewdeal.org/us/tx/houston-tx/ ↵

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 19. ↵

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 19. ↵

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3 ↵

- Dr. Olen Cole Jr., Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), NCpedia, 2010. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 19. ↵

- Dr. Olen Cole Jr., Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), NCpedia, 2010. ↵

- Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid.,17 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 18 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 4. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Christopher Alejo, David Arriaga, Snethia Bell, Le’azha Booker and, Carolina Camacho Torres provided that content (Fall 2019). ↵

- Alex Jack, “Reformer in the Promise Land,” Saturday Evening Post, vol.212 issue 4 (1939): 9, http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=18748134&site=ehost-live&scope=site. (accessed October 10, 2019). ↵

- Ibid., 10. ↵

- “Exit the Curmudgeon,” Time Magazine, vol 59 issue 6 (1952): 26, http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=54166068&site=ehost-live&scope=site. (accessed October 03,2019). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Nobody’s Sweetheart,” Times Magazine, vol 38 issue 11 (1941): 16, http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=54828599&site=ehost-live&scope=site. (accessed October 03,2019). ↵

- Exit the Curmudgeon,26 ↵

- Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S History Textbook, Vol 1: to 1877 (Sandford University Press,2019),456, http://www.americanyawp.com/text/23-the-great-depression/ (accessed October 08, 2019). ↵

- Open Stax,The First New Deal (Rice University,2019), https://cnx.org/contents/p7ovuIkl@4.3:Sx4c72lG@6/The-First-New-Deal (accessed October 11,2019). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- https://livingnewdeal.org/us/tx/houston-tx/ ↵

- “The Feminine Mystique.” American Perspectives: Readings in American History, Pearson Custom Publishing, 2006, pp. 665-675. ↵

- Wandersee, Winifred D. “‘I’D RATHER PASS A LAW THAN ORGANIZE A UNION’: Frances Perkins and the Reformist Approach to Organized Labor.” Labor History, vol. 34, no. 1, Winter 1993, pp. 5–32. ↵

- Debrework Tassew, Fall 2019. ↵

- Feiner, Susan. “The Revolutionist.” Women’s Review of Books, vol. 26, no. 6, Nov. 2009, pp. 6–9. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=45463749&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Wasser, Solidelle. “The Life of Frances Perkins.” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 132, no. 6, June 2009, pp. 69–70. EBSCOhost, ↵

- Wasser, Solidelle. “The Life of Frances Perkins.” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 132, no. 6, June 2009, pp. 69–70. EBSCOhost, ↵

- Debrework Tassew, Fall 2019. ↵

- Wandersee, Winifred D. “‘I’D RATHER PASS A LAW THAN ORGANIZE A UNION’: Frances Perkins and the Reformist Approach to Organized Labor.” Labor History, vol. 34, no. 1, Winter 1993, pp. 5–32. ↵

- “Frances Perkins.” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, May 2019, p. 1. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=134487562&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Breitman, Jessica. “Frances Perkins.” FDR Presidential Library & Museum, www.fdrlibrary.org/perkins. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kristin Downey. The Woman Behind the New Deal. Anchord Books, 2009. p. 48. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Kotlowski, Dean, reviewer. Ibid book review in Labor History, vol. 54, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 348–350. ↵

- https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Roosevelt_I_Knew.html?id=hE3vGmTivTcC&source=kp_book_description ↵

- Guzda, Henry P. "Frances Perkins' Interest in a New Deal for Blacks." Monthly Labor Review 103, no. 4 (1980), 33. Accessed March 15, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41841218. ↵

- Ibid., 34. ↵

- Ibid., 54. ↵

- This paragraph by Joel Flores, Spring 2020. ↵

- Lumen Learning, “US History II (OS Collection),” Lumen, accessed October 18, 2019, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ushistory2os2xmaster/chapter/the-second-new-deal/. ↵

- Lauren Coodley, Upton Sinclair : California Socialist, Celebrity Intellectual. (Lincoln: Bison Books, 2013), http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=603914&site=eds-live. ↵

- Greg Mitchell, “‘Upton Sinclair’s EPIC Campaign.’ ” (The Nation. 2010), http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.242484359&site=eds-live. ↵

- Lauren Coodley, Upton Sinclair : California Socialist, Celebrity Intellectual. (Lincoln: Bison Books, 2013), http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=603914&site=eds-live. ↵

- Greg Mitchell, “‘Upton Sinclair’s EPIC Campaign.’ ” (The Nation. 2010), http://search.ebscohost.com.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.242484359&site=eds-live. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Samuel Brown, Daniel Diaz, Vanessa Garza, Andrea Gonzalez, Glenda Gonzalez. Fall 2019. ↵

- James T. Patterson. “The New Deal in the Wes,” Pacific Historical Review Vol 38, No. 3 (Aug., 1969), pp 317-327 (11 pages), DOI: 10.2307/3636103 ↵

- James F. Wickens, ” Colorado in the Great Depression: A Study of New Deal Policies at a State Level” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Denver, 1964); Micheal P. Malone, “C. Ben Ross and the New Deal in Idaho” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Washington State University, 1966). ↵

- History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Soil Conservation in the New Deal Congress,” ↵

- “Resettlement Administration (RA) (1935),” Living New Deal, accessed November 14, 2019, https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/resettlement-administration-ra-1935/) ↵

- Department of Agriculture, Circular No. 33, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1928, pp. 1 and 22. ↵

- History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “Soil Conservation in the New Deal Congress,” ↵

- Kennedy, American Pageant, 788 ↵

- Saloutos, Theodore. "New Deal Agricultural Policy: An Evaluation." The Journal of American History 61, no. 2 (1974): 394-416. doi:10.2307/1903955, 397. ↵

- Davis, Chester C. "The Program of Agricultural Adjustment." Journal of Farm Economics 16, no. 1 (1934): 88-96. www.jstor.org/stable/1230785 ↵

- Kennedy, American Pageant, 789 ↵

- Arrington, Leonard J. "Western Agriculture and the New Deal." Agricultural History 44, no. 4 (1970): 337-53. www.jstor.org/stable/3741519. ↵

- Saloutos, 398 ↵

- Ashley Nandlal, Kim Nguyen, Adam Obregon, Nidia Perez, Guadalupe Rangel, Fall 2019. ↵

- David P. Billington, Jackson C. Donald, and Melosi V. Martin, The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design, and Construction in the Era of Big Dams. (Denver: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, 2005), 329. ↵

- April Farnham, “‘Their Sleep Is to Be Desecrated’: The Central Valley Project and the Wintu People of Northern California, 1938-1943,” Ethnic Studies Review 30, no. 1 & 2 (2007): 148, accessed December 1, 2019, https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1276&context=esr. ↵

- Ibid., 155. ↵

- Ibid., 144. ↵

- Ibid., 136. ↵

- Ibid., 156. ↵

- Ibid., 151. ↵

- David Wilkins, The Navajo Political Experience (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013), 21 https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Navajo_Political_Experience.html?id=DeNAnsAHfpEC. ↵

- White, Richard. The Roots of Dependency : Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change Among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos. Vol. [1st pbk. ed., 1988]. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 1988. 264-65 http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=45461&site=eds-live. ↵

- Ibid., 263. ↵

- Nicholas Flanders, “Native American Sovereignty and Natural Resource Management,” Human Ecology 26, no. 3 (1998): 437, accessed November 27, 2019, www.jstor.org/stable/4603290. ↵

- David Wilkins, 21-22 ↵

- For concerns related to the proposed raising of Shasta Dam, see: https://news.berkeley.edu/2019/03/04/federal-effort-to-raise-shasta-dam-by-18-5-feet-is-getting-some-serious-pushback/. ↵