32 Civil Rights in Education and Sports

This chapter is on the 20th-century civil rights movements in education and sports. Civil rights movements and activities such as #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and others will be covered in later chapters.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND EDUCATION

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

Homer Plessy was arrested for sitting in the White section of a Louisiana railroad. He sat in the White section to deliberately challenge the law by getting arrested. An ex-Union office named Albion Tourgee was Plessy’s attorney. Eventually coming before the Supreme Court, Justice Henry Brown wrote: “A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races—a distinction which is founded in the color of the two races, and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color—has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races, or re-establish a state of involuntary servitude. Indeed, we do not understand that the thirteenth amendment is strenuously relied upon by the plaintiff in error in this connection.”[1] In other words, creating the separate but equal clause to the Constitution.

There are six major building blocks to the Brown decision.

Murray vs. Maryland (1936)[2]

I believe is one of the most dynamic and attention-grabbing cases in American history. The trial was a result of the unfairness of the American policies for education. Normally the unfairness circulated around African Americans who longed for higher education. One man, in particular, sought a higher education that would better his life. His name was Donald Gains Murray.[3] He sought admissions into the University of Maryland School of Law. His application was rejected due to the fact that he was an African American male. He was advised that he should attend either Howard or a less accredited law school in Maryland. This did not sit will with Murray because he was an honor student from Amherst and was well qualified for admission into the law school of his choice. Murray was determined that he would attend law school in Maryland.[4]

His actions toward challenging the University of Maryland made him a great candidate for the motion known a NAACP. This was an organized group which stood for National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The NAACP began a concerted effort to erode the legal underpinnings of segregation in America.[5] Murray was represented by Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston in the case known as University of Maryland v. Murray. These attorneys initially sought to demonstrate that states systematically failed to provide African American students equal resources and facilities.[6] The main argument was that the University of Maryland rejecting Murray from attending the school was a breach of the fourteenth amendment. Houston argued that if African Americans wanted to practice law in Maryland and could not attend the University of Maryland. Which was the only law school in the state.[7] Houston masterfully manipulated representatives from the state and the University of Maryland on the witness stand. He was able to get them to state for the record that the only reason Donald Murray was rejected was due to his race.[8] Houston suggested that if Murray could not attend that school then there was a need to build one that was equal to the University of Maryland in order to maintain the separate but equal clause. The judge found there was no need to build a separate law school for negros ruled in favor of Murray. The dean was ordered to admit Donald Murray into the University of Maryland law school.[9] This was the first victory of Houston and Marshall. Murray became the first African American to graduate from the University’s law school in 1938.[10] The victory not only exposed the educational inequalities African Americas suffered, but also inspired young people to support the associations lawsuits too end discrimination in education.[11]

I believe that Donald Murray was an extremely brave man to stand up for justice in a time where black African American men were not taken seriously. Murray knew his potential and made a courageous move towards appealing his case. If he didn’t do so, then NAACP would have never known about him and many other students might not of had the courage to speak up and demand equal rights. Murray knew that he was more than qualified for admission into the University of Maryland law school and did not take his rejection lightly. Along with the assistance of Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston, they tackled the unfairness of segregation in the educational system. Thanks to Donald Murray and his appeal so he could attend the school of his choice, America’s education system was making strides into the right direction which was equality.

Gaines v. Canada (1938)

Charles Hamilton Houston joined the NAACP with the belief that the Plessy decision could be overturned in its entirety by picking at its threads by starting with education. The University of Missouri denied Lloyd Gaines admittance into its law school because Gaines was black. Rather, the state offered to send Gaines to a school outside of Missouri and to pay for his expenses. Houston argued that Missouri was required under the Plessy decision to either admit Gaines into their law school or to build a law school for blacks. The Supreme Court agreed thus requiring every state to either dismantle their segregationist laws pertaining to graduate school or to build separate facilities for black graduate students.

Smith v. Allright (1944)

Primary elections were for white voters only. White only primaries were designed to ensure that no black candidates would be on the general election ballots. Such as in Texas. Thurgood Marshall was the attorney for the injured party. In 1944 the Supreme Court found on the side of the NAACP: “The right to vote in a primary for the nomination of candidates without discrimination by the State, like the right to vote in a general election, is a right secured by the Constitution.”[12]

Sweatt v Painter (1946)

Herman Marion Sweatt was a veteran and a mail carrier in Houston, Texas when he applied for law school at the University of Texas. The Texas Attorney General said if a separate facility could not be found then, Sweatt could be admitted into UT. The case went to the Supreme Court. Justice Vinson said: “”The law school, the proving ground for legal learning and practice, cannot be effective in isolation from the individuals and institutions with which the law interacts. Few students and no one who has practiced law would choose to study in an academic vacuum, removed from the interplay of ideas and the exchange of views with which the law is concerned.”[13]

Sipuel v. Board of Regents University of Oklahoma, (1948)

Ada Lois Sipuel wanted admission into the University of Oklahoma law school but was denied based on color. The state said they would build her an equal law school. Attorneys argued separate law schools would be inherently unequal. They won and the University of Oklahoma was required to admit Sipuel into the University of Oklahoma law school. “New challenges awaited Sipuel inside the classroom, including sitting in a segregated seat marked “colored” that was roped off from the rest of the class. She also had to eat in a separate chained-off guarded area of the law school cafeteria. Her lawsuit and tuition were supported by hundreds of small donations, and she believed she owed it to those donors to succeed. With the support of classmates, professors, and family, she graduated in 1951 with a law degree from the University of Oklahoma. After passing the bar, Sipuel practiced law until 1956, when she left legal practice to work as the public relations director for Langston University. She became a full-time faculty member in 1959, eventually becoming head of the school’s social science department. She returned to the University of Oklahoma, where she earned a master’s degree in the late 1960s, and in 1991 she received an honorary doctorate from the law school. In 1992, Sipuel’s life came “full circle” when she was appointed by Governor David Walters as a member of the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.”[14]

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Reagents (1950)

George McLaurin sought entrance into a PhD program at the University of Oklahoma. Unlike Ada Sipuel, McLaurin sued for the unequal treatment on campus, and won. “Even though the university could no longer deny McLaurin a place in school, it tried to segregate him on campus. He had to sit by himself in a separate section of the classroom, sit at a separate desk in the library, and sit at a different table (and sometimes eat at different times) from the rest of the students in the cafeteria. The federal court in Oklahoma City upheld the discrimination, observing that the Constitution “does not abolish distinctions based upon race . . . , nor was it intended to enforce social equality between classes and races.” Such reasoning, though common in courts up to that time, was about to lose all legitimacy. The U.S. Supreme Court heard McLaurin’s appeal in April 1950 and in June unanimously reversed the lower court. Chief Justice Fred Vinson, writing for the court, held that the differential treatment given to McLaurin was itself a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause: “Such restrictions impair and inhibit his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.” McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950) signaled that the Supreme Court would no longer tolerate any separate treatment of students based on their race.”[15]

The Brown Decision (1954)

Linda Brown was prohibited from attending the school nearest her because that school was for whites only. The NAACP took up the case, along with several others, arguing that segregation in education was a violation of children’s Fourteenth Amendment rights. Thurgood Marshall was the leading attorney. Chief Justice Earl Warren took one year to produce a decision because he wanted the Court to speak with a unified voice, believing the decision was too monumental to have any dissension. In 1955, Warren said: “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”[16]

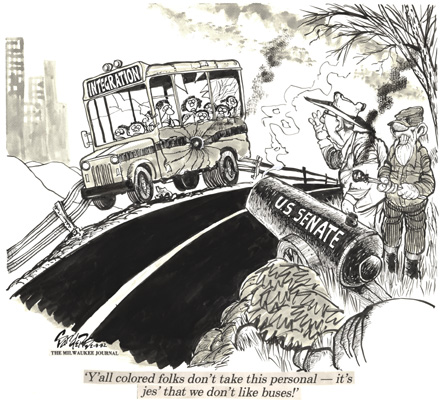

In 1955 the Court issued Brown II, declaring desegregation to happen “with all deliberate speed.” A vague time frame indeed. In 1971, the parents of six-year-old Jimmy Swann sued their school district, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, as their son was still attending a segregated school. A federal judge ordered the school district to engage in bussing to settle the issue. The Supreme Court agreed. Bussing was a touchstone to violence in the North. People sliced the tires of busses, set busses on fire, rigged busses with bombs, and fired weapons at buses, causing buses to be guarded by local and state law enforcement. Of course, the violence that followed bussing was not about bussing.[17]

Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC) drafted a bill to cut funding to school districts for transportation.[18] Here is an editorial cartoon from the Milwaukee Journal about that.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND SPORTS

The first African American professional football player, Charles W. Follis, was born February 3, 1879, in Cloverdale, Virginia. The Follis family moved to Wooster, Ohio, where he attended Wooster High School and participated in organizing and establishing the first varsity football team. He played right halfback and served as team captain on a squad that had no losses that year.

In 1901, Follis entered the College of Wooster. Rather than playing football for the college, he played for the town’s amateur football team – the Wooster Athletic Association, where he earned the nickname of the “Black Cyclone from Wooster.”

In 1902, Frank C. Schieffer, manager of the Shelby Athletic Club secured employment for Follis at Howard Seltzer and Sons Hardware Store in rural Shelby, Ohio. The six-foot, 200-pound Follis played for Shelby in 1902 and 1903.

In 1904, Follis signed a contract with the Shelby Athletic Club, later the Shelby Blues. With that contract, he became the first professional African American football player. Follis played on the team with Branch Rickey, the Ohio Wesleyan University student and future Brooklyn Dodger owner who would sign Jackie Robinson to integrate major league baseball in 1947.

Like other players who integrated sport teams, Follis faced discrimination. Players on opposing teams targeted Follis with rough play that resulted in injuries. At a game in Toledo in 1905, fans taunted him with racial slurs until the Toledo team captain addressed the crowd and asked them to stop. In Shelby, Follis joined his teammates at a local tavern after a game; the owner denied him entry. At the Thanksgiving Day game of the 1906 season, Follis suffered a career-ending injury.

Follis turned to baseball, a sport he played for many years in the spring and summer. Having played for the Wooster College and in the Ohio Trolley League, Follis was an experienced baseball player, but could only play in segregated baseball leagues. He played for the Cuban Giants, a black baseball team, as a catcher.

On April 5, 1910, at the age of 31, Follis died of pneumonia in Cleveland, after playing in a Cuban Giants game. He was buried in Wooster Cemetery in Wooster, Ohio.[19]

Baseball

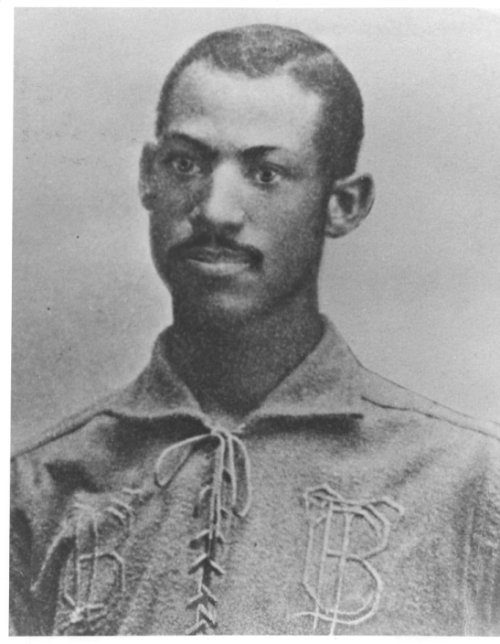

Long before Jackie Robinson, there was Moses Walker. Moses Fleetwood Walker was born on October 7th, 1857 in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. He made his major league debut in May 1884, playing as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association. In a 1919 interview and many years after retiring from baseball, Tony Mullane, Walker’s teammate in the Blue Stockings and one of the most outstanding pitchers of the 19th century, referred to Walker as “the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals”.[24]

Fleetwood had to face several challenges during his time as a major league player. He suffered insults from opponents and fan abuse because of his skin color. According to Williams “Besides hisses and boos, there were real threats to his physical wellbeing in the other southern city—Richmond. The manager of his team, Charles Morton, received the following letter in the mail: We the undersigned do hereby warn you not to put up Walker, the negro catcher, the evenings that you play in Richmond, as we could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes on the grounds in a suit. We hope you will listen to our words of warning so that there will be no trouble, but if you do not there certainly will be.”[25]

Another incident that resulted in him being discriminated against was when his team had an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings and the manager of this team, Adrian “Cap” Anson, refused to play if Moses took part in the game. Anson was considered a leader of the white supremacy community in baseball. Eventually, he and his followers pulled out black players from the Majors and excluded them from playing organized baseball not because of their lack of ability but because of their color. This action reflected the national attitude against black people.[26]

After Fleetwood Walker was released from a major league baseball team, there was no more presence of black players in the big leagues until 1947 when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, becoming the first African American man to play baseball in the modern era. Goldstein took an extract from Zang’s book “Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer” (1995), ”Walker and Robinson had some common experiences, but while Robinson played at a time when the historical tide was carrying society toward integration, Walker stood as a nearly solitary figure attempting to play ball as an ebb tide swept away from popular support for racial equality”.[27] Unfortunately for Fleetwood, his presence was only noticeable for teammates, opponents, and fans for his race and not for his performance during the games.

He began his career as a pitcher, and the first documented account of his appearing in a game was with Chelsea, Massachusetts, in April 1878. Later that month, pitching for Lynn Live Oaks of the International Association, he defeated Tommy Bond and the famed Boston Nationals, 2-1, in an exhibition game. Over the next few seasons, he played with Worchester of the New England Association (1878), Malden of the Eastern Massachusetts League (1879), Guelph, Ontario (1881), and the Petrolia Imperials (1881). After 1884, when he finished with a 7-8 record with Stillwater, Minnesota, of the Northwestern League, he did not pitch substantially.

Eventually, he became an everyday player and, while he could play any position, second base became his preferred spot. He continued to play in white leagues, appearing with Keokuk in the Western League (1885), Pueblo in the Colorado League (1885), Topeka in the Western League (1886), Binghamton in the International League (1887), Montpelier in the New England League (1887), Crawfordsville in the Central Interstate League (1888), Terre Haute in the Central Interstate League (1888), Santa Fe in the New Mexico League (1888), Greenville in the Michigan League (1889), Galesburg of the Central Interstate League (1890), Sterling of the Illinois-Iowa League (1890), Burlington of the Illinois-Iowa League (1890), Lincoln-Kearney of the Nebraska State League (1892), and the independent Findlay, Ohio, team (1891, 1893-1894, 1896-1899).

In the early days of baseball, there was no official color line, and he played in organized baseball with white ball clubs until the color line became established and entrenched. However, his stays were almost always of short duration despite his playing ability-probably because of the race factor. In 1887 he was dropped from Binghamton of the International League and was forbidden to sign with another International League team. [He played with numerous teams throughout the Midwest in the 1880s and 1890s.] In 1909, with Fowler in failing health, several attempts were made to play a benefit game for the ailing baseballist, but the efforts all proved unfruitful and the game never materialized. Less than three years later, the “real first” black professional baseball player died of pernicious anemia after an extended illness, just eighteen days short of his fifty-fifth birthday.

Source: James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994.

Octavius Catto, 1866-1868

“Catto helped found and became a star player for and captain of the Pythian Base Ball Club, a black entrant to the city’s new most popular sport. (It was supplanting cricket.) The Pythians’ first game, against the Albany Bachelor in 1866, was a 70-15 loss. But it was their only defeat of the season; they ended with “a 9-1 record and the acclaim as the best colored team in the city and perhaps the nation,” Biddle and Dubin report. The following year, Catto’s team applied for membership in the state chapter of the National Amateur Association of Base Ball Players, hoping to schedule games against white teams. Association leadership blocked the application from coming up for a vote. Catto then drafted a proposal that the Pythians join the national association, rather than the state chapter. Its convention voted overwhelmingly not to admit “colored clubs.” The following year, the Philadelphia Olympics accepted the Pythians’ citywide challenge to white teams, and a match was set. The game lasted three hours, and the Olympics won, 44 to 23. (Pitching must have been interesting.)”[29]

“Catto’s social and political connections with white businessmen and white baseballists were crucial to the team crossing bats with white organizations. … It is important to contextualize these efforts in relation to the efforts of other black clubs during the period. Catto appears to have played hardball with the white organizers, and they responded in kind. It was as much politics as it was baseball. Many of these white players were hardcore Democrats; Catto was a Republican who pushed for black male suffrage and citizenship. Catto died shortly after the formation of the Pythian nine, but the club forged ahead and evolved into a powerful force on the baseball scene in the 1870s and 1880s. That influence culminated in the spring of 1887, when the Pyths spearheaded the creation of the first known, organized black hardball league in history, the NCBBL.”[30]

Charles Follis also played baseball:

Basketball

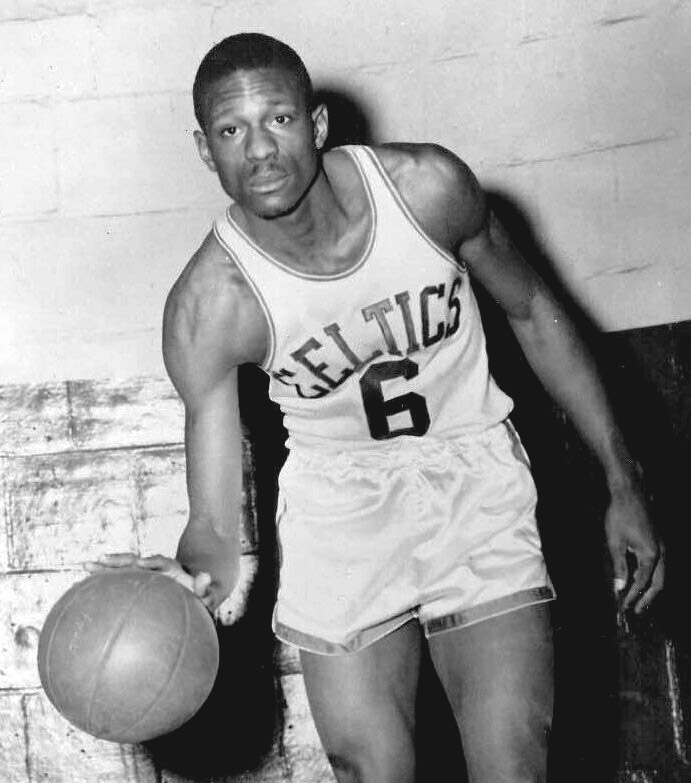

Early Lloyd[31] was born April 3, 1928 in Alexandria, Virginia. He honed his basketball skills on the playgrounds of inner-city Washington, D.C., just a short walk from home. He graduated from West Virginia State University in 1950 and was drafted by the Washington Capitols that same year, along with two other black players (Chuck Cooper and Nat Clifton). On October 31, 1950, 21-year-old Earl Lloyd became the first black player to step on an NBA court in the season opener for the Washington Capitals. By this time, Major League Baseball and the NFL had integrated. So a good question would be why was the NBA the last major American sport to integrate? Anyhow, “[a]t 6’5″ and 200 pounds, his role was to battle under the boards and shoot only rarely, which was one reason for his modest 8.4 points-per-game output.”[32] Cooper was the first black player drafted in the NBA (Boston Celtics) but because of the NBA’s schedule, the Washington Capitals just happened to have played before the Celtics (Cooper) and New York Knicks (Clifton). Lloyd was actually the third black player drafted by an NBA team, but the first to play an NBA game.

He once mentioned that “It took him two years to remember that his parents had named him “Earl.” In playing arenas like Baltimore and Indiana, all they ever called him was “nigger.”[33] “The highlight of his career came in the 1954–55 season when he scored 731 points and helped the Nationals to the Eastern Division Championship.”[34] He was recognized as one of the top defensive players in the NBA and honored in 2000 when the NBA commemorated the 50th anniversary of African American players in the NBA.

Athletes As Activits

.

And he continued doing that up until his death in 2022. His accomplishment as a player and a civil rights activist was shown through his life and legacy. He became the first black NBA coach in history and paved the way for many to be considered. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contribution to civil rights.[45] And he also fought for others. Bill Russell went through his fair share of these experiences throughout his life, but that didn’t stop him from standing up for what he thought was right.

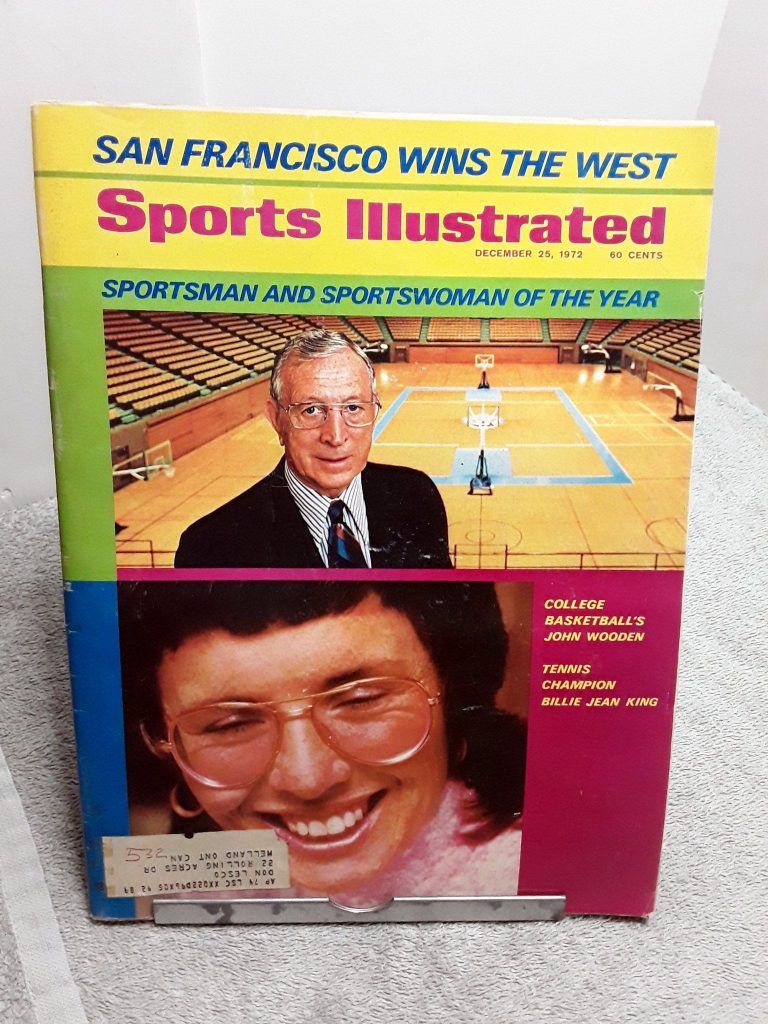

King, then 29, played Riggs on September 20th, 1973 to a packed Astrodome and before a worldwide television audience. I remember watching this match from my parents living room in Wisconsin (not thinking I’d be in that town some 28 years later). She handily beat the aged sexist.

I want to thank my students Amanda Peters, Mariell Edwards, and Don Pam for their interest in these topics, and the dedication, time, and energy necessary to bring these histories alive. Their contributions enhanced this chapter.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- https://www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/texts/judgement-of-the-supreme-court-of-the-united-states-in-plessy-v-ferguson ↵

- by Amanda Peters ↵

- Jessie, Smith, Linda, Carney T. (Wynn, Inc Recorded Books, and Lean’tin L. Bracks) The Complete Encyclopedia Of African American History. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press, (2015) p.423 ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Joseph, Locke and Ben, Wright. The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open Textbook , Vol 1:To 1877. p.26 ↵

- Jessie, Smith, Linda, Carney T. (Wynn, Inc Recorded Books, and Lean’tin L. Bracks) The Complete Encyclopedia Of African American History. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press, (2015) p.423 ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Gordon, Andrews. Undoing Plessy : Charles Hamilton Houston, Race, Labor, and the Law, 1895-1950. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: (Cambridge Scholars Publishing) 2014.p173 ↵

- Jessie, Smith, Linda, Carney T. (Wynn, Inc Recorded Books, and Lean’tin L. Bracks) The Complete Encyclopedia Of African American History. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press, (2015) p.423 ↵

- S., Mintz, & S.,McNeal. Digital History.(2019). ↵

- Thomas, Bynum L. 2013. NAACP Youth and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1936–1965. Vol. 1st ed. Knoxville: (Univ Tennessee Press.) p.12 ↵

- https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_smith.html ↵

- https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2012/10/10/162650487/sweatt-vs-texas-nearly-forgotten-but-landmark-integration-case ↵

- http://crdl.usg.edu/collections/sipuel/?Welcome ↵

- https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=MC034 ↵

- https://www.ourdocuments.gov/print_friendly.php?flash=false&page=transcript&doc=87&title=Transcript+of+Brown+v.+Board+of+Education+%281954%29 ↵

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/12/opinion/sunday/it-was-never-about-busing.html ↵

- https://www.nytimes.com/1975/09/18/archives/anti-busing-measure-approved-in-senate.html ↵

- https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/follis-charles-w-1879-1910/ ↵

- Most of what follows was written by my student Mariell Edwards ↵

- Kelly, Kate. America Comes Alive.https://americacomesalive.com/2016/02/04/kenny-washington-broke-color-line-in-nfl/. ↵

- Graser, Geoff. The NFL was segregated until Kenny Washington broke the color barrier in Los Angeles”. https://timeline.com/kenny-washington-black-nfl-32e2f52a8b98. ↵

- By Cynthia Romero, Fall 2019. ↵

- Goldstein, Richard. “Moses Fleetwood Walker.” The New York Times, 2019, p. 11. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Goldstein, Richard. “Moses Fleetwood Walker.” The New York Times, 2019, p. 11. ↵

- https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/fowler.html ↵

- https://www.phillymag.com/news/2016/06/10/octavius-catto-memorial/ ↵

- https://www.inquirer.com/philly/sports/phillies/Philadelphias_Pythians_made_baseball_history_in_1800s.html ↵

- This was part of a student essay. ↵

- Taylor, Phil, and Ted Keith. “Earl Lloyd 1928—2015.” Sports Illustrated, vol. 122, no. 10, Mar. 2015, p. 14. ↵

- Bell, Harold. “Earl Lloyd--the Perfect Case for Black History.” New York Amsterdam News, vol. 90, no. 17, 22 Apr. 1999, p. 46 ↵

- “Early Lloyd, CIAA Keynote Speaker.” New York Amsterdam News, vol. 93, no. 8, 21 Feb. 2002, p. 47. ↵

- https://www.nbcsports.com/bayarea/49ers/trump-anthem-protesters-get-son-b-field ↵

- https://www.cnn.com/2016/09/12/sport/colin-kaepernick-nfl-opening-day-reaction-trnd/index.html. ↵

- https://theundefeated.com/features/the-cleveland-summit-muhammad-ali/ ↵

- Ibid ↵

- From the website: "The Undefeated is the premier platform for exploring the intersections of race, sports and culture. We enlighten and entertain with innovative storytelling, original reporting and provocative commentary." ↵

- https://theundefeated.com/features/the-cleveland-summit-muhammad-ali/ ↵

- Jackson, Ashawnta. “How Bill Russell Changed the Game, on and off the Court.” JSTOR Daily, August 22, 2022. https://daily.jstor.org/how-bill-russell-changed-the-game-on-and-off-the-court/ (last accessed July 25, 2023). ↵

- Jones, Dustin. “As a Racial Justice Activist, NBA Great Bill Russell Was a Legend off the Court.” NPR, August 1, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/01/1114795613/racial-justice-pioneer-nba-bill-russell (last accessed July 25, 2023). ↵

- Bieler, Des. “Bill Russell Led an NBA Boycott in 1961. Now He’s Saluting Others for ‘Getting in Good Trouble.’” The Washington Post, August 27, 2020.