3 British Colonial North America to 1676

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

“Why can’t we all just get along?” -Rodney King, 1992[1]

Spain and Its Competitors

The Western Hemisphere was quickly being gobbled up by European powers in the fifteenth century. Spain controlled the largest part that covered nearly all of South America, Central America, Mexico (New Spain), and Florida to California (New Mexico). Spain remained true to Rome following the Reformation.

France controlled the northern reaches of the hemisphere, parts of what is today Canada and the upper Midwest (such as Wisconsin and Michigan) and called their dominion New France. France remained true to the Catholic church.

And finally, the Dutch controlled the upper eastern seaboard (centered on what is today New York and New Jersey) and called their territory New Netherlands. Fort Orange was their capital (now named Albany). The Dutch were the only Protestant nation in the Americas.

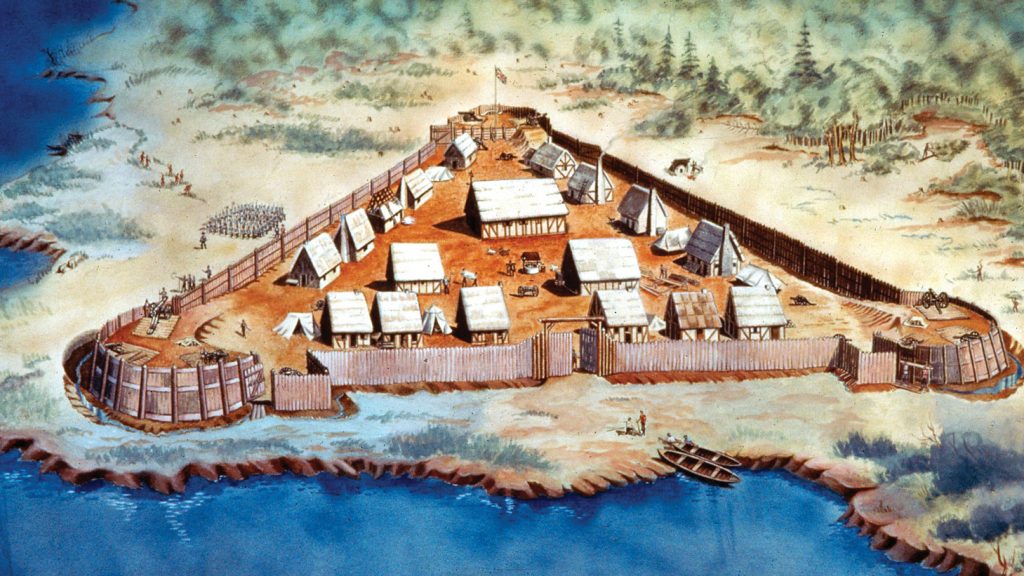

The first British colony in the Americas was Roanoke, which was a failure. The first successful British colony in North America was called Jamestown. Founded in May of 1607 on an island off the coast of present-day Virginia, Jamestown was a Joint Stock colony. There were three types of British colonies: Joint Stock, Royal, and Proprietary. All three had the goal of making money. The Royal colony existed to make money for the British Crown (George III by the time we to the American War for Independence). Most of the British colonies in the Caribbean were royal charter colonies. The Proprietary colony was owned by a single person or family and thus was designed to make money for the person or family that owned the colony (such as Pennsylvania). And, the Joint Stock colony was owned by the investors, designed to make money for the investors (such as Jamestown).

It was expensive to start a colony: you needed ships, people, equipment, security forces, building supplies, tools, weapons, and food. So a Joint Stock colony would sell shares (a percentage of the total). Once the colony sold enough shares, the settlers would head off to the Americas. They would find natural resources, ship them back to England, and thus make money for the colony, money that would be returned to the shareholders. Initially, there was just one natural resource that English settlers were interested in finding: gold! That’s not going to work out, except on rare occasions such as in California around 1848, the Black Hills around 1876, and Alaska in the early 20th century.

Virginia is the first and Massachusetts is the second colony. Someone who appears in the history of the creation of both colonies is Stephen Hopkins. From the New England Historical Society’s web page: “Stephen Hopkins settled both Jamestown and Plymouth, and many believe Shakespeare based a character on him. Though he wasn’t among the first Jamestown settlers, he did arrive within the first three years. He might have gotten there sooner but for a shipwreck – a shipwreck that probably inspired Shakespeare to write The Tempest.”

“Shakespeare portrayed him as a drunken clown with ambitions of grandeur. In real life, Stephen Hopkins narrowly avoided execution for mutiny and later ran into trouble with the Plymouth authorities for over serving the patrons of his tavern. Stephen Hopkins was born in 1581 in Hampshire, England. By 1604, when he’d reached his mid-20s, he lived in Hursley, Hampshire; he had married Mary Kent. They lived with her widowed mother, Joan Kent, and kept a small alehouse in Hampshire. Hopkins’ mother-in-law apparently liked to sample the product. In 1605, Joan Kent was charged with being a common tippler and fined fourpence.”

“By 1608, Mary and Stephen Hopkins had three children: Elizabeth, Giles, and Constance. In 1609, Stephen Hopkins got a job as a minister’s clerk, probably to help support his growing family. In his new job, he read religious work. Two months into the voyage, a hurricane separated the Sea Venture from the rest of the flotilla. Lashed by the storm for three days, the Sea Venture began to leak badly. Seawater reached nine feet in the hold when land — Bermuda — was sighted. The ship ran aground and all 150 people aboard made it safely to land. The castaways quickly discovered they’d landed in paradise, and they lived on the island’s fresh water, pigs, turtles, and birds.”

“Nearly all of them survived for nine months in Bermuda. While there, they built two small ships from Bermuda cedar and parts salvaged from the Sea Venture. On May 10, 1610, Stephen Hopkins and the surviving castaways set sail for Jamestown. Eleven days later, they arrived in Virginia. A report of the shipwreck reached England, as did tales of the castaways. In November 1611, Shakespeare’s play The Tempest first appeared on the English stage. In a comic subplot, the drunken power-hungry butler named Stephano tries to depose the island’s ruler, Prospero. Many scholars believe the Sea Venture‘s wreck inspired Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. Many also think Stephen Hopkins inspired Stephano because of an incident on Bermuda.”

“As the castaways labored to build their boats, Stephen Hopkins started questioning the authority of the group’s governor, Sir Thomas Gates. He argued they should sail to England, not Jamestown. Gates had him arrested and charged with mutiny. Hopkins was found guilty and sentenced to death. But he pleaded for his life with ‘sorrow and tears,’ and so many castaways begged mercy for him he received a pardon. From then on, Stephen Hopkins wisely avoided controversy.”

“In Plymouth, Stephen Hopkins proved useful for his knowledge of the American Indians, gained during his stay in Jamestown. When Samoset first approached the settlers, he spent the night in Stephen Hopkins’ house. The Hopkins household survived that first grim winter, only one of four in Plymouth to escape death. Stephen and Elizabeth had five more children and they ran a tavern. By 1630, he began to get into trouble with the Puritan authorities. The court fined him for allowing drinking and shuffleboard on Sunday, for overcharging his customers, and for letting his customers get drunk. The court also committed him to custody for refusing to support a servant who gave birth out of wedlock. Stephen Hopkins died in 1644. In his will, he asked to be buried next to his wife, and left his possessions to his surviving children.”[2]

Jamestown

The colony of Jamestown had several objectives. First, find gold. Second, find a direct route to the South Seas, and third, find the lost colony of Roanoke. The initial wave of colonists was adventurers/explorers. Young men who sought to find their fortune by bending over and picking up gold, then heading back to England where they would purchase a house and some farmland, and live comfortably the rest of their lives. The English inheritance system was primogeniture, which means that all wealth goes to the eldest son. Good news if you were son number one. The other sons had to find their own fortune, and many of the Jamestown colonists were the sons that would not inherit anything from their fathers. After a rough ocean crossing (45 men died), 101 men and four boys arrived at what they called Jamestown (after King James of England) along the Powhatan River they renamed the James.

BTW, Powhatan was the title of a local Indian chief as well as the name of a local Indian tribe. Powhatan had a daughter, Pocahontas. The first set of colonists found no gold, although the Powhatan seemed friendly enough. Due to disease and insect infestation, two-thirds of the settlers died within the first seven months. In 1609, the crown published a recruitment pamphlet called Nova Britannia (New Britain). The pamphlet was designed to attract new investors and new colonists. The pamphlet promised plentiful food, beautiful mountains, lots of gold, and excellent weather. The pamphlet promised the good life without lots of work. In fact, the pamphlet said that the “savages are ready and willing” to be converted to God and would do the basic chores of cooking and cleaning for the colonists. In a nutshell, Nova Britannia promised wealth for the monarch, lumber to strengthen the English navy, and promised personal prosperity for those who took up the challenge.

Now not everyone was allowed the opportunity for affluence. Parliament prohibited “con men,” Catholics, and “evil politicians” from going to Virginia. When the first group failed to find the gold, they realized that their stay in Jamestown was to be longer than expected and that they would have to begin farming in order to provide for their own food. The Powhatan Indians initially brought the starving colonists food and tried to teach them to farm in the Indian tradition. Colonists responded by raiding the tribe’s food warehouses so the chief, Powhatan, stopped giving or selling food to the colonists. Tensions rose. The winter of 1609-1610 was particularly long, cold, and deadly. Of the 500 colonists who began the winter, only sixty made it through. Famine was rampant. And the survivors turned to cannibalism. A dark part of Virginia’s past not to be found on the Virginia quarter (State Quarters Program) or any one of their commemorative license plates.

Possibly the first news of what happened at Jamestown reached England in late Spring of 1610. The Spanish ambassador wrote to his king:

Sire—From Virginia, there has come to Lyme, a harbor of this Kingdom, a ship of those that remained there lately, and those who arrived in it, report that the Indians hold the English surrounded in the strong place which they had erected there, having killed the larger part of them, and the others were left so entirely without provisions that they thought it impossible to escape because the survivors eat the dead, and when one of the natives died fighting, they dug him up again, two days afterward, to be eaten.[3]

As the months went on, more and more stories and details of what happened were circulated by various organizations. For example, the joint-stock company that ran the Jamestown colony, the Virginia Company of London reported how an unhappy marriage ended in the death of both spouses:

There was one of the companies who mortally hated his wife and therefore secretly killed her, then cut her in pieces and hid her in divers parts of his house. When the woman was missing, the man suspected, his house searched, and parts of her mangled body were discovered. To excuse himself he said that his wife died, that he hid her to satisfy his hunger, and that he fed daily upon her. Upon this, his house was again searched, where they found a good quantity of meal, oatmeal, beans, and peas. He thereupon was arraigned, confessed the murder, and was burned for his horrible villainy.[4]

Then there were the stories of the salted wives, acknowledgments by Captain John Smith and Virginia’s General Assembly. The purpose here being there was no doubt what happened in Jamestown during the “Starving Time.” That won’t happen again until 1847 when a party, led by George Donner, while moving out west tries to beat the weather by taking a believed to be short cut. The shortcut wasn’t there and the whole Donner Party did not make it to California.

Nevertheless, some of the survivors built rudimentary boats and tried to make it back to England. They were intercepted by several boats of new colonists (and supplies). In 1614, the Jamestown colonists finally discovered the gold -in the form of tobacco. It turns out that the soil, temperature, and weather in Virginia are perfect for growing tobacco. Although tobacco harvesting is labor-intensive, it yielded high returns. The land-owning colonists were making money, but they needed more bodies in order to grow their colony and therefore make even more money, so Parliament created the Headright System; an effort to get settlers to go to Virginia by offering fifty acres of land to each settler who could afford to pay his way to British colonial America. The Headright System was not as effective in raising the number of colonists as the English government initially had hoped for, but it did raise tension between indentured servants (who under the Headright system really had no chance of owning land) and landowners as well as indentured servants and slaves. Finally, we newly freed indentured servants and slaves headed west, there existed endemic warfare between Native Americans and people of European and African descent.

Virginia

The Jamestown colony became a small city within the larger colony of Virginia. After the failure of the Headright System, England began transferring debtors prisoners to Virginia to work in the tobacco fields. The prisoners were allowed to work off the rest of their sentences in Virginia, after which they would be allowed to stay in Virginia. Of course, the prisoners were not making any money while they worked during their prison sentences. The other kind of people allowed to come to Virginia were indentured servants. Indentured servants could not pay to move to the colonies so a wealthy investor would bring them over and in doing so the person would incur debt.

According to English Common Law, the debt would be paid off based on the type of work performed -faster if manual labor, longer if domestic work, for example. Upon paying off the debt, the indentured servant would receive a new suit of clothes, a letter identifying the servant as now free, and tools that the servant used while working off the debt.

The idea was the person would now go down the road, maybe to a new town, and strike it rich. The land was the currency of the day. It takes money to purchase land. Developed land is more expensive than undeveloped land and the land in and around Jamestown, or any town, was simply out of reach for average colonists. Thus the prisoners and servants pushed west.

This westward expansion moved the frontier further west and resulted in a rise in conflict with the various Indian tribes. Warfare was endemic in Virginia. Wars against Powhatan, his brother Opechancanough. Continued success, both militarily and diplomatically, resulted in the Virginia colony expanding beyond the York and then the Rappahannock rivers, putting the Powhatans again on the offensive. The British succeeded in repulsing all Indian assaults. That same time (1619) wealthy men created a self-governing body called the House of Burgesses. Even after Virginia’s charter went from stock to royal, this first-of-its-kind governing body continued to meet, albeit with limitations. Revolutionary-era leaders who cut their teeth in the House of Burgesses included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry.[5]

1619[6]

From the days of early settlers in America, women were viewed as an object or commodity by men. Women were shipped from Europe to the Americas. The first boat of women, that was intended for marriage, landed in 1620. They were sent by people who wanted the colonies to be successful and therefore needed men to create families. Men also received more land if they were married.[7] The women were only available to wed free men of the planting class. If the man wanted to take a woman as his bride, he would pay 120 pounds of leaf tobacco.[8] This is the beginning of the similarities between plantation women and slave women. Just like slave women, plantation women were essentially sold for profit, although those in charge of the potential brides claimed the monetary charge imposed on men for a bride was for transportation expenses.[9] This first shipment of ninety women was so successful that sponsors sent over two more shipments of fifty women each. After more success with those shipments, the private sector decided to bring in their ships of women and increased the price of leaf tobacco to 150 pounds. Just like female slaves who were quadroons, one-fourth black, or mulattoes – of one white and one black parent, the increase in demand drove up the price for women. Slave mart records reveal that girls, who were light-skinned quadroons and mulattoes, brought in higher bids than darker slave women.[10]

Massachusetts

Unlike most of the Chesapeake or southern colonies which were established to make a profit (cash crops on large farms or plantations growing such things for external consumption such as indigo, rice, and tobacco), New England colonies tended to be established for religious reasons and by families, especially congregations. Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church in Rome, creating the Church of England with himself as the temporal and religious leader. The Anglicans’ religious ceremonies tended to resemble those of the Roman church. The major difference, initially, between the Anglican Church and the Catholic Church was that religious leaders in the former were allowed to get married. Anglicans even said the Nicene Creed.

Puritans were unable to change the Anglican Church in England thus they decided to migrate to British colonial America. The first Puritan colony in British colonial America was called the Massachusetts Bay colony. Like Virginia, certain groups were prohibited from settling there to include Catholics and Quakers. Massachusetts Bay was established in 1630 and was led by John Winthrop Sr.

Now religion can be an important aspect of peoples’ lives. As you get older you tend to become more conservative in your religious views, but overwhelmingly people do not turn their backs on the religion of their fathers. Individuals do, but not groups. Individual Jews may shift their belief system to embrace Christianity but a community of Jewish people tends not to become Christians. Mormons do not become Congregationalists. But that was what Henry VIII asked the people of England to do when he broke from Rome.

One group of English people believed that the Anglican Church did not go far enough in breaking with all Roman traditions, yet they also believed that the Church of England would not change. These people, called Separatists (a sect of the Puritans), wanted to create their own separate church -separate from the Church of England. Separatists moved to Holland, but their attempts to create a new religious community failed. So in 1620 they loaded up their belongings and set sail for British America. The pilgrim leader was William Bradford. They were also called Pilgrims. They named their new colony Plymouth after the English town from which many of them were originally from. Leaders of the Separatists created an agreement called Mayflower Compact. The Mayflower Compact was British colonial America’s first political agreement: that called for the creation of a political body with the power “to enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most met and convenient for the general Good of the Colony.”[11]

Massachusetts was founded/established/populated by Puritans. Those who wanted to purify the Church of England were called the Puritans. Now Puritans were English followers of a protestant minister named John Calvin. Calvin emphasized predestination, a lack of free will, and the belief that humans were depraved and needed a strong religious government to control their animal instincts. Puritans also believed in predestination, election by God who is saved (the nagging Puritan question was “Am I saved?”).

They valued education. For example, Harvard was established in 1636 specifically to train Puritan ministers. Puritans supported intolerance – error must be opposed and driven out. Such as the persecution of Anne Hutchinson. Hutchinson was a member of the original Puritan group that established Massachusetts Bay. Only men could become ministers (the only religion that allowed women to lead church services were the Quakers -see “Middle Colonies” below). And women were prohibited, by tradition, from public speaking.

Anne Hutchinson challenged both when she proclaimed that God wanted women to become ministers, then she began leading church services in her house. Initially, Hutchinson led what I think would resemble bible study classes, but just for women. She was charismatic, knowledgeable and a brilliant speaker. Those in attendance invited other women, then men, and then those bible study classes began to resemble religious services. In addition, Hutchinson began to critique the sermons of most Puritan ministers of the area. She argued that those ministers were preaching salvation through good works ( Catholic belief) while ignoring the Puritan position is that salvation is something to be bestowed -the grace of God.

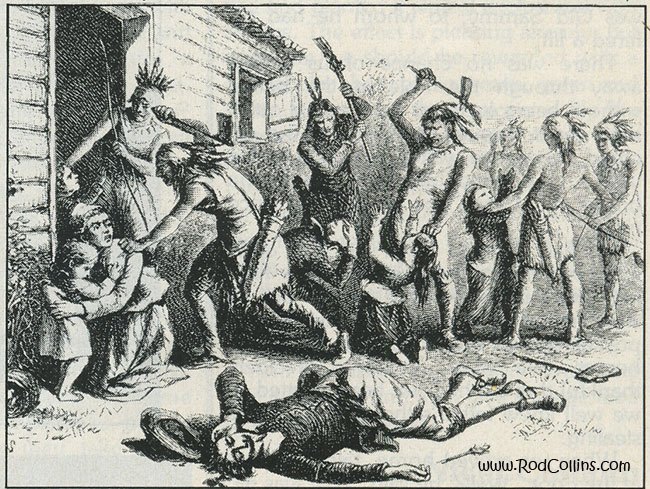

At that point, Hutchinson was arrested and tried. Her defense was that God told her to become a minister. The judge rejected her evidence and banished Hutchinson from the colony. She will meet up with Roger Williams and helped establish Rhode Island (colonists outside of RI referred to that colony as “the sewer”). Hutchinson headed to New York, the Bronx I believe, near New Jersey, along with 4-5 of her children. There was a conflict with one group of Indians when one day a group of Indians attacked the neighborhood, shooting arrows into Hutchinson, killing her. Word of Hutchinson’s demise reached her family and friends in Massachusetts Bay. “We were right,” is what they felt. If God had wanted women to speak in public and become ministers, He would have saved her from the arrows of the Indians. Instead, Hutchinson’s death as “proof” that God did not want women to speak in public or become ministers.

Another Puritan dissenter was Roger Williams. Williams did not support the collection of taxes to support the established churches. Rather, Williams believed that churches should be supported by voluntary tithes. He also held the notion that Indians should be paid for their lands. These two ideas, which were out of step in Puritan Massachusetts, got Williams kicked out of the colony. So he left to establish a new colony – Rhode Island, with complete religious freedom for all Christians.

Rhode Island’s Charter, which served as state constitution until 1842, includes this forward-looking provision: “No person within the said Colony, at any time hereafter, shall be any wise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion, in matters of religion, who does not actually disturb the peace of our said Colony; but that all and every person and persons may, from time to time, and at all times hereafter, freely and fully have and enjoy his own and their judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments, throughout the tract of land heretofore mentioned, they behaving themselves peaceably and quietly and not using this liberty to licentiousness and profaneness, nor to the civil injury or outward disturbance of others.”[12]

Back to John Winthrop. Winthrop was both the religious and political leader of the first Puritans in Massachusetts. And he came to America aboard the English ship the Arbella. Before leaving the ship, Winthrop gave a speech to his shipmates. In a nutshell, the speech, entitled “A Modell of Christian Charity,” is an explanation as to why they are there and what they will do there. Puritans were to create, Winthrop said, a perfect community. A new city on the hill (a new Jerusalem). Politically, socially, economically, and religiously perfect. In fact, their colony would become the most perfect, greatest colony in the history of the world, and people from around the world will try to emulate the Puritans, forever. And if they fail, then God is ready to cast them into the pits of Hell. Here’s an excerpt from that 1630 sermon:

“For wee must consider that wee shall be as a citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us. Soe that if wee shall deale falsely with our God in this worke wee haue undertaken, and soe cause him to withdrawe his present help from us, wee shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. Wee shall open the mouthes of enemies to speake evill of the wayes of God, and all professors for God’s sake. Wee shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants, and cause theire prayers to be turned into curses upon us till wee be consumed out of the good land whither wee are a goeing.”[13]

That is a lot of pressure to put on people who already believed the Devil walked among them, watched each other for signs of being under the Devil’s influence, and believed the wrongdoings of others could spell disaster for the community. They were an anxious community of busybodies. Now John Calvin’s idea of the covenant was between one person and God: one person promises to live according to God’s laws and God promises not to kill the person prematurely and cast him into the pits of Hell. Winthrop’s idea of the covenant linked the community at large with God’s vengeance. Everyone in the Puritan community will live a Christian life and in exchange, God will bless everyone with health and wealth. Now if just one person in the community breaks just one of God’s laws, then God can kill everyone in the community and cast everyone into the pits of Hell. Again, this is putting tremendous pressure on the colonists.

In Massachusetts Bay, the church members controlled the civil government, and church membership was limited to those who were predestined to go to Heaven. Wealth and health were two signs that a Puritan was predestined for Heaven. Why would God waste prosperity on someone who is going to Hell? So the church members were typically the wealthy members of the Puritan society, which meant the economic elites controlled the civil government. Church membership dropped in the late seventeenth century (coincided with bad economic times and failed harvests) so in 1662 the Puritan leaders created the Halfway Covenant: any adult person who had at least one parent as a church member could join the Puritan church without having to “prove” that they are predestined to enter Heaven.

Maryland

Maryland (named after Henry VIII’s Catholic daughter Mary) was founded in 1634 by George Calvert and his son Cecilius (the second Lord Baltimore), staunch Catholics, as a refuge for England’s Roman Catholics. Like Virginia, tobacco was wildly successful in Maryland. And not unlike Virginia, Maryland initially had a difficult time in growing its population, thus Maryland’s leaders decided on employing the indentured servant strategy. One reason why so few people migrated to British colonial America was the cost -they could not afford the cost of the venture. So what Maryland did was to pay for poor people to move to Maryland. Once in the colony, indentured servants undertook a debt -they had to pay back the costs of getting them to Maryland. So, indentured servants would work for the person holding the debt for a period of three to seven years. Less time if the labor was intensive (such as tobacco harvesting) or longer if the work was less demanding (such as being a nanny for the children). After the debt was paid in full, the owner of the debt would give the debtor a new set of clothes and new tools and be set free to find their own success in Maryland. Like the ex-prisoners in Virginia, the ex-indentured servants in Maryland began moving west, which meant they came into increasing contact with Indians.

There were several religious toleration acts passed during the colonial period. The one in Maryland was passed in part because Catholics were not able to build their Wall therefore Protestants were migrating into the colony and Catholic leaders feared what could happen if Protestants one day took controlled the colony. Their Toleration Act did not “tolerate” one who did not believe in the Trinity, the penalty for this offense being death. Anyone “speaking reproachfully concerning the Virgin Mary or any of the Apostles or Evangelists was to be punished by a fine, or, in default of payment, by a public whipping and imprisonment. The calling of anyone a heretic, Puritan, Independent, Popish priest, Baptist, Lutheran, Calvinist, and the like, in a “reproachful manner”, was punished by a light fine, half of which was to be paid to the person or persons offended, or by a public whipping and imprisonment until an apology was made to the offended. This act was drawn up under the directions of Cecilius Calvert himself.”[14]

Attacking Catholics or Catholicism has been low-hanging fruit for over 500 years. I have a lecture on this entitled “Non-White, Non-English speaking, non-Protestant (“un-American”) need not apply” that I will try to remember to type out and add to a later chapter on xenophobia (typically examined in the late nineteenth-century rise of modern America, Populism, Progressive era, late Gilded Age, stuff like that.

This begins when Virginia and Massachusetts refused to allow “papists” from settling in those colonies and by the 21st century certain anti-immigration views are code for anti-Catholic positions.

The various acts of “religious toleration” during the colonial era excluded Catholics, who could be put to death for being Catholic (death for Unitarians, Muslims, and Atheists as well). Before the Civil War, Catholic Irish were portrayed in the press as drunks. The Know-Nothings were anti-immigrant in general and anti-Catholic in particular calling for prohibitions on holding political office, from entering the US, some within the party even sought the prohibition of Catholicism itself in the US.[15] More on this later and on how immigration became code for anti-Catholicism.

Southern Colonies

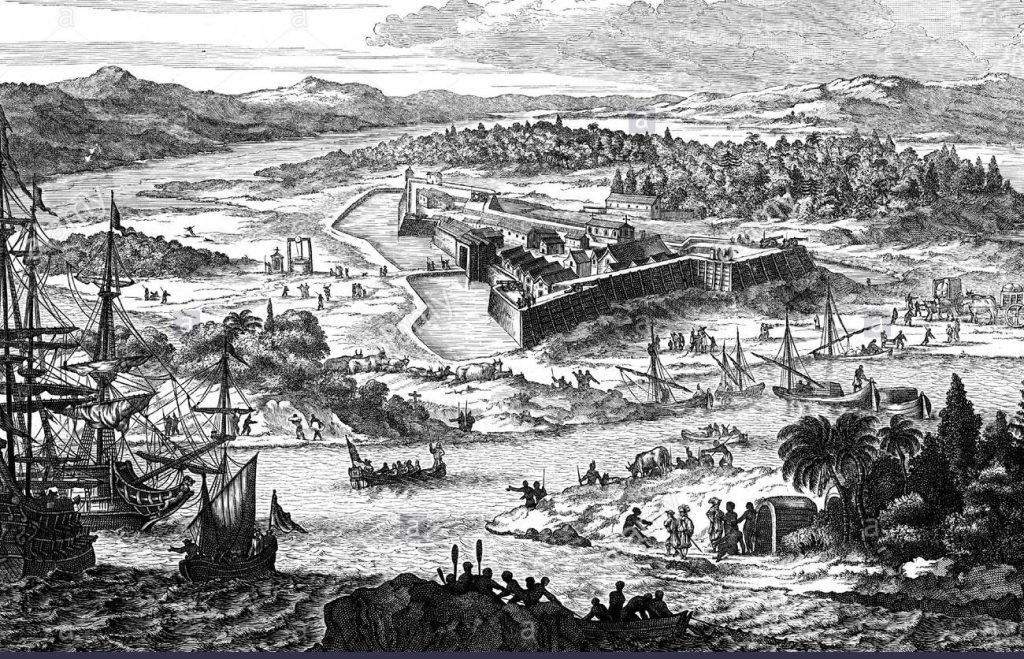

Barbados was a proprietary colony owned by Sir William Courten. My the middle of the 17th century, there were more English emigrants in the West Indies than in any other area in British colonial North America, although most of those were indentured servants. Initially, a tobacco-based economy, sugar replaced tobacco in the middle of the 1600s along with the introduction of African slaves as sugar is very labor-intensive.

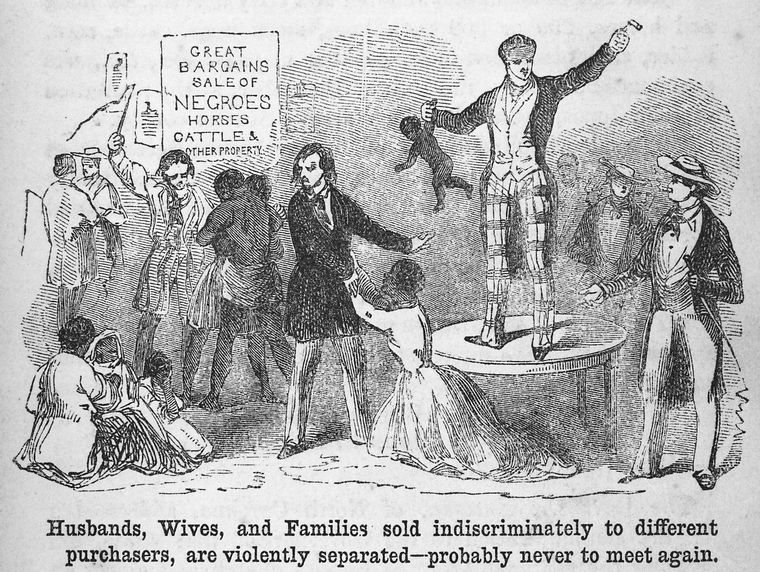

Due to the number and percent of the population of slaves, the British rulers developed the first slave Code. The Code provided the legal basis for slavery and established the rights and responsibilities of slave owners (even the reality that slaves had no rights). It also stated that slaves had no rights and were totally under the control of their owners, imperturbably. Now Barbados made a lot of money for the crown, but as the island colony only produced sugar, its inhabitants needed everything else and so Parliament created the colony of the Carolinas in 1653. The Carolinas existed to grow all the food that the people on Barbados would need. Some Carolina farmers discovered that if you plant three crops, they can be harvested at different times of the year, thus farmers could make even greater profits than if they just grew a single crop. The combination was rice, tobacco, and indigo. Indigo was a tuber used in the dying of cloth purple or dark blue. Very shortly, Carolina planters were making more money than the sugar planters on Barbados, thus Barbados’ colonists migrated to the Carolinas, and brought their slaves with them. Eventually, the Carolinas would be split into North and South Carolina.

So many Barbadian slaves were brought into what became South Carolina, then in South Carolina black people outnumbered white people. Colonists of the Carolinas first tried to use local Indians as slaves, however, Indians had no experience in growing rice but West Africans did know how to cultivate rice. They also knew how to tend cattle and plant sugar, so Africans quickly replaced Indians as the choice for slaves in the Carolinas.

Georgia

England made a lot of money from the Carolinas. English leaders feared that the Spanish would try to invade the British colonies from the Spanish colony of Florida and seize the Carolinas (much in the same way that England supplanted the Spanish in the Caribbean). Spain had sent raiding parties into the Carolinas already. So Parliament decided to create a colony with the purpose of slowing down the inevitable Spanish attack from Florida. They called that new colony Georgia, which was established with the help of James Oglethorpe in 1733.

Georgia would be populated by people let out of debtor’s prison. In England, it was against the law to be unable to pay your debts. Men, when they did not pay their debts, would be thrown into Debtor’s Prison. Parliament decided to give these criminals a second chance by allowing them to start their lives over again this time in the colony of Georgia. Because these colonists were inherently poor, Parliament wanted them to find jobs and thus Parliament initially forbade slavery in Georgia thus white landowners would hire white debtor’s prisoners. “Georgia had always been a ‘melting pot,’ welcoming the persecuted and prosecuted of Europe including large groups of Puritans, Lutherans, and Quakers.”[16]

The only group not welcome in Georgia were slaves as noted above. However, there will be about 15 years of fighting between Georgia and the Spanish in southern Georgia causing a drain to Parliament, to the extent that Parliament noted that Georgia was no longer economically viable. So Parliament will allow Georgia to become a slave colony as a way of once again becoming self-sufficient. Slavery is the savior for the colony but James Ogenthorpe was gone.[17]

The Middle Colonies (New York and Pennsylvania)

New York was originally a Dutch colony with its major port city of New Amsterdam (now New York), the major population center of New Ark (now Newark, NJ), and its colonial capital at Fort Orange (now Albany). England and the Dutch fought a series of naval wars in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries over trade routes and trading posts. The end result was that England took the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in 1664 and renamed it New York.[18]

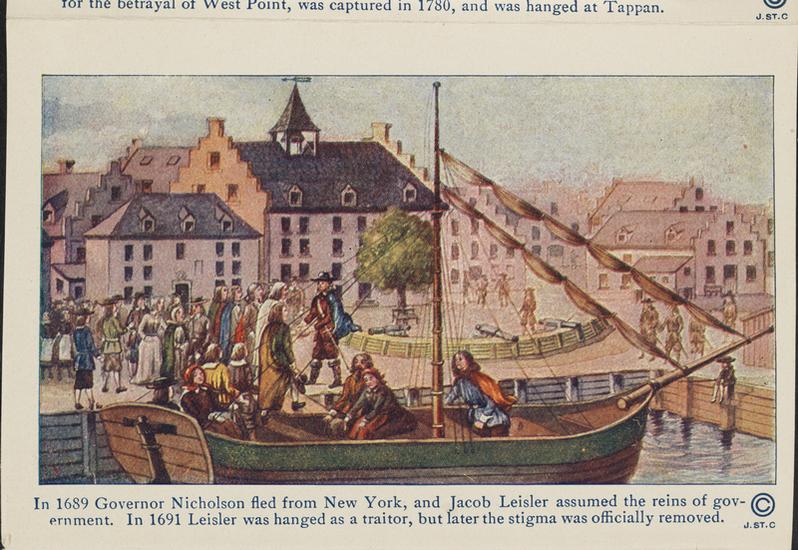

Now New York had some problems. First, New York did not grow economically. For example, about five or six English men owned most of New York and they rented lands called patroonships. It was actually cheaper to buy land than rent however there was very little land available to purchase, so the population outside of New York City did not grow. The wealthy elite who owned most of New York did not want to sell the land because they had hoped the price would go up dramatically, so they just rented the land. However, people simply came to New York and squatted -they lived on parcels of land without having proper ownership of the land. And the land that was sold tended to have vaguely drafted boundaries between parcels of land. That resulted in another major problem: Lawyers. Lawyers flooded into New York in large measure to try land cases in colonial courts. Some lawyers sided with the squatters while others sided with the landowners. Either way, lawyers got paid. Meanwhile, farmers could not farm and even the port of New York was horrifically underused. Another major problem was political infighting. For example, in 1689 the German Protestant Jacob Leisler fomented a successful rebellion.

Non-Catholics in the British colonies were concerned that James II, in France, would support a French rebellion in the Americas. “In New York as well, democratic movements were afoot. An armed mob seized Fort James and installed Jacob Leisler, a militia commander and immigrant from Germany, as the head of a new government. Leisler’s willful personality was similar to that of Peter Stuyvesant, but for a while, he enjoyed popular support because he established a legislative assembly that was not dominated by the wealthy merchants and landowners. Leisler’s rule was short-lived.”[19]

The new, Protestant king sent a new governor to take control of the situation. Leisler was convicted of treason and executed. Hanging him was not good enough. His head was then cut off, his heart was cut out and displayed. Eventually, the parts will be put back together and Jacob Leisler will be buried.

The First Amendment is a very American invention. No other country has such a collection of rights and free speech is the cornerstone of the A1C. Even though the New Yorker Donald Trump has made statements that suggest he does not support a free press, the First Amendment has its roots in New York’s idea of a free press.[20] John Peter Zenger published a newspaper called the Gazette.

The governor of New York, William Cosby, was a known thief and gambler in his youth, and degenerate in various manors to include a propensity for tyranny. Zenger routinely published Cosby’s exploits in his paper. The governor had Zenger arrested and had Zenger charged with libel. During the trial, we find out that what Zenger published was factual. The stories were just embarrassing to Cosby. Zenger was found not guilty.

Libel is when you publish or have published something inaccurate or not factual. Publishing things that are simply embarrassing to an elected official or demonstrate that an elected official is lying is not libel. For example, an elected official declares repeatedly that he did not commit adultery with a porn star (while the elected official’s wife was pregnant with their son), was not complacent in bribing the porn star to stay quiet on the alleged adultery, and repeated these assertions of innocence while onboard an official government aircraft with cameras recording from numerous media outlets. “Did you know about the $130,000 payment to Stormy Daniels?” “Do you know where he got the money to make that payment?[21] Reporting that answers are inconsistent with facts is neither libel nor “fake news.”

President Ronald Reagan, October 6, 1983: “There is no more essential ingredient than a free, strong and independent press to our continued success in what the founding fathers called our ‘noble experiment’ in self-government.”[22]

And on August 2, 1985, Reagan joined Congress in observing Freedom of the Press Day. Note the reference in the Proclamation to Zenger.

Pennsylvania

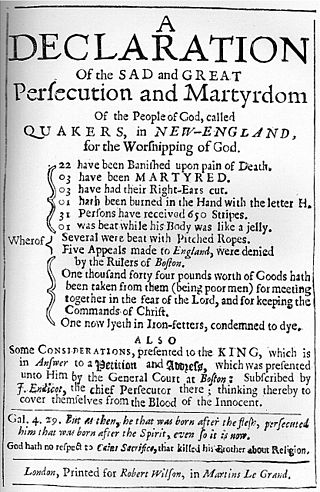

Chartered in 1681 and founded the next year as a proprietary colony under William Penn, Pennsylvania was originally created to be a haven for England’s Quakers (the Society of Friends) . Quakers’ history in the other colonies was inconsistent. Sometimes Quakers were outright prohibited from settling. Sometimes Quakers could settle there but were arrested if they engaged in public displays of religion, such as in the cases of Mary Fisher and Ann Austin.[23]

Quakers populations in Massachusetts Bay vacillated depending on the laws and how the laws were applied. Roger Williams established Rhode Island, in large part, as a safe haven for all religious dissenters, but he primarily had Quakers in mind. Over time lawyers took towns then colonies to court to try to overturn laws prohibiting the existence, in any form, of Quakers. I thought that while out of office, Gov. John Winthrop Jr. acted as attorney for a group of Quakers in one of these cases. I will have to look into this. In Connecticut, I think. I did find this quote. From what looks like a personal/amateur history web page containing biographies of Connecticut governors, there’s an exception of an article on John Winthrop written by Frederick Norton in 1905. From that excerpt, Norton quotes George Bancroft on Winthrop: “Puritans and Quakers and the freemen of Rhode Island were alike his eulogists. The Dutch at New York had confidence in his integrity, and it is the beautiful testimony of his father that ‘God gave him favor in the eyes of all with whom he had to do.”[24] I found the entire article (including the same quote) through Google Books on page 66 of The Connecticut Magazine, Volume 7, September 21st, 1942. Edited by William Farrand Felch, George C. Atwell, H. Phelps Arms, Francis Trevelyan Miller. From all over British colonial North America, Quakers migrated to the newly created safe haven for Quakers in the early 1680s. Or, the Quakers got kicked out of all the good colonies. So that is why Pennsylvania is central to the history of Quakers in the United States.

There was no such thing as “the Quaker beliefs” of “the Quaker creed.” There were different types of Quakers from evangelical to nontheists, each having its own set of beliefs, responsibilities. Along the spectrum, where did William Penn fall? That should be easy. What about the big-time suffrage leaders such as the Grimke sisters? The names for the types of Quakers used today (Evangelical, Liberal, Holiness, Traditional, Nontheist) were not all used in this period of US history and those that were used in the 1700s are in use today do not have the same definitions or meanings. Words, meanings, change over time. “Liberal” in 1750 is different than “Liberal” 2015.

Finally, keep the following in mind, not just about Quakers but about many of the liberal Christian religious traditions of the seventeenth-nineteenth centuries and many of the social reformers. First, they worked with each other, knew each other, or at least were aware of each other. People involved in the reform movements of the early to mid-nineteenth century tended to work together. They also knew each other socially. And they religious paths intertwined, especially among the most liberal of the Christian traditions: Quakers, Unitarians, and Universalism making it difficult to separate their actions as part of a Quaker, Unitarian, or Universalist belief system. I would argue that the importance of what people do is what people do. Step 1: record their actions. Step 2: determine why they did what they did. The reformers of the 1820s or the 1890s were not interested in helping to alleviate the problems of the tired, the poor, or the huddled masses yearning to breathe free because some deity says so. Reformers address the needs of society because it’s the right thing to do.

The Christian group in the US with the greatest percentage of atheists, deists, agnostics, I believe, are the UUs (Unitarian-Universalism). And both the Unitarians and the Universalists (who predate the American Revolution) have been the most liberal Christian traditions in this country, regardless of when. UUs (the two groups merged in 1961) were social reformers in the 1830s and 1960s. In fact, two of the four people killed during Selma (1965) were Unitarians. The question is, where along the religious spectrum do they fall? And the answer is “Who cares?” Like the daughter of the UU layperson who was murdered said “[E]ven if she was not involved in any church, she would have gone anyways; that is who she was.”[25]

In other words, trying to neatly place each historically significant Quaker based on the branch or particular strain of Quakerism is a burdensome task as there will be a lot of historically significant Quaker reformers/activists/volunteer/progressives from the reform of the first half of the nineteenth century (think Dorothea Dix), their work in support of the troops during the Civil War, and their work as pacifists towards the end of their lives), was significant to that religious group. The Quakers were viewed both as progressive and quaint.

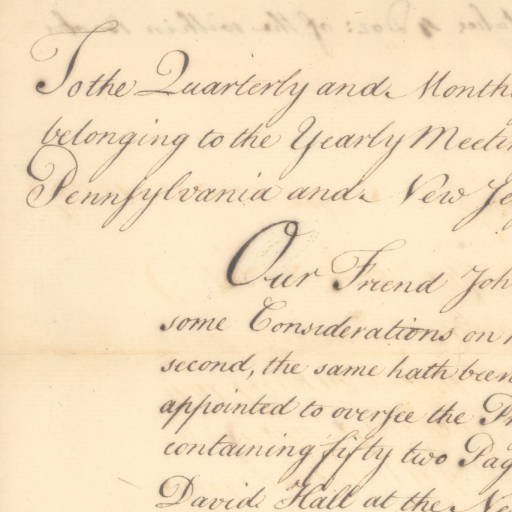

During the colonial period, Quakers embraced a few general ideas: refused to swear oaths; abstention from alcohol; not steal Delaware Indians’ land or in any way cheat them out of their land; they were pacifists; they would dress plainly (subdued colors, no patterns, heavy wool); and opposition to slavery to the extent that Quakers will be associated with the abolitionist movement. For example, one of the earliest anti-slavery tracts was written by the Quaker John Woolman. While Quakers opposed slavery, Quakers did not prohibit slavery. Quakers would eventually prohibit fellow Quakers from owning slaves and John Woolman played a role in that. According to the Special Collections website at Byrn Mawr, which hosts a page entitled Quakers and Slavery:

“Woolman began to question and speak out against slavery while working as a scribe. His employer instructed him to write the bill of sale for a slave. Despite being troubled by this Woolman wrote the bill of sale ‘but at the executing of it I was so afflicted in my mind, that I said before my master and the Friend that I believed slave-keeping to be a practice inconsistent with the Christian religion.'”

“In the year 1746 Woolman spent time traveling with Isaac Andrews through Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina observing slavery firsthand. He wrote his essay Some considerations on the keeping of Negroes protesting slavery on religious grounds. He held onto this essay for some years and in 1754 the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting approved its publication. Unlike many of Woolman’s predecessors in the antislavery movement, Woolman took a gentler approach more accepted by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. He does not directly attack slaveholders but stresses equality. Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Friends published their own antislavery paper Epistle of Caution and Advice, 1754 urging against the buying and keeping of slaves.”[26]

Overall there were not standardized ministers but women did lead religious activities for women and men did so for men. Women had the right to speak in public and these Quaker communities attracted women who were interested in both of those opportunities.

The relationship between the Quakers and the Indians was amicable because of the Quakers’ friendliness and Penn’s policy of purchasing land from the Indians.[27] Penn tried to protect the Indians in their dealings with settlers and traders. “The relationship was so peaceful that the Quakers often used the Indians as babysitters. Penn even went so far as to learn the language of the Delaware Indians, and for nearly fifty years the two groups lived in relative harmony.”[28] However, Penn’s acceptance of all people was a double-edged sword for the Indians, because as many non-Quaker settlers came to the colony they undermined Penn’s benevolent policy.[29]

The Quakers who were the dominant religious group in Pennsylvania were predominantly English. Non-Quaker, non-English groups that migrated to Pennsylvania included Germans, Scotch-Irish, and the Amish. The colony became prosperous primarily due to an exceptionally diverse economy: wheat, corn, flax, and hemp farming plus an abundance of industries to include printing and publishing, textile production and pig iron, sawmills. Finally, Philadelphia became a commerce and transportation hub.[30]

Dissent

Between the English Civil War (1642-1651) and the Glorious Revolution (1688), England lost control of the colonies at times. England also tried to reassert its control of the colonies.

New England Confederation, 1634-1684. “As a result of the Pequot War of 1637, New England settlements were receptive to plans for strengthening colonial defenses against the threat of Indian attacks. Leaders in Hartford advanced the idea of forming a defensive alliance among like-minded settlements in the area — a proposal that pointedly excluded the Anglican residents in Maine and the free-thinkers of Rhode Island. After several years of negotiations, delegates from Connecticut, New Haven, Massachusetts Bay, and Plymouth Colony met in Boston in 1643 and formed The United Colonies of New England, more commonly known as the New England Confederation.”[31]

Each member colony would have two delegates. Meetings were held on a regular basis. The main threat came from feared Indian attacks but the secondary threat was from the Dutch and the tertiary threat was from the French in Canada. The was no new government created, rather the Confederation would have the power to require member colonies to return escaped fugitives and runaway slaves.

Massachusetts Bay Colony, the largest in the Confederation, didn’t like seemingly giving up the same authority as the smaller colonies, so Massachusetts decided to to not adhere to directives. The Confederation will go the way of the dodo. Later, on the eve of the French and Indian War, seven colonies would give consideration to Ben Franklin’s Albany Plan of Union, a proposal for a federated colonial government.”[32]

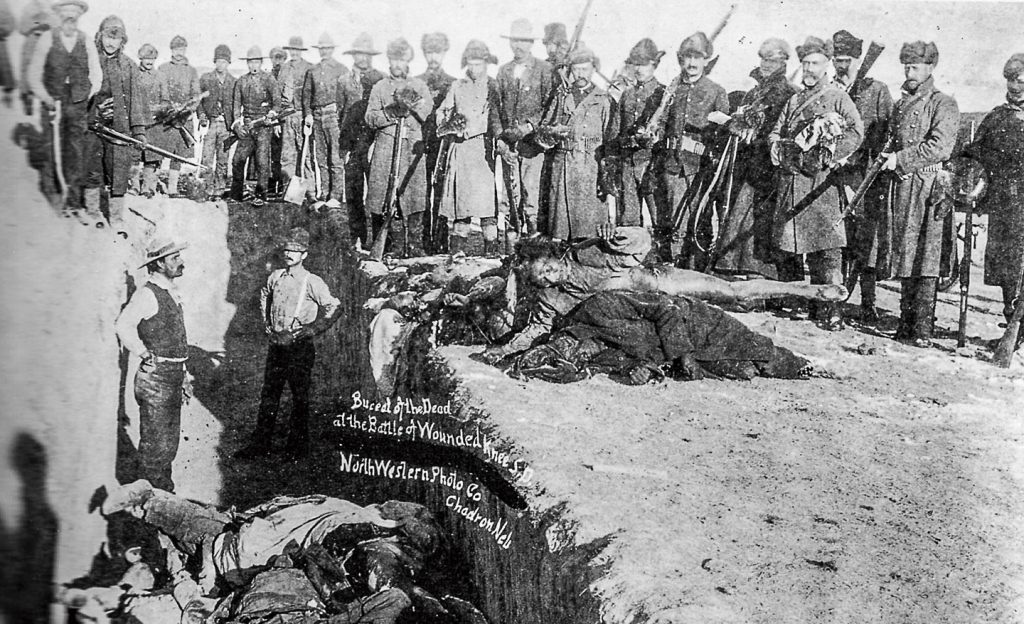

Again, Anglo-Indian warfare was endemic. 400 years of war that will come to an end on December 29th, 1890 in what the US government will call the Battle of Wounded Knee, which took place in South Dakota. In what became Massachusetts and Rhode Island, there was the Pequot War (1636-1638). Then King Phillip’s War in New England (1675-1678). King Williams War was a massive conflict among New England colonists, British troops and their Native American supports against French troops and their Indian supporters. Fighting took place in New England, Canada, the Great Lakes area between 1689 and 1697. A dress rehearsal or a preview of the French and Indian War (1754-1763)?

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wounded_Knee_Massacre#/media/File:Woundedknee1891.jpg

Bacon’s Rebellion, 1676

“[We must defend ourselves] against all Indians in general, for that they were all Enemies.” This was the unequivocal view of Nathaniel Bacon, a young, wealthy Englishman who had recently settled in the backcountry of Virginia. The opinion that all Indians were enemies was also shared by many other Virginians, especially those who lived in the interior. It was not the view, however, of the governor of the colony, William Berkeley.[33]

As indentured servants paid off their debt and gained their independence, they migrated West. Typically, they encountered Indians who sometimes reacted with violence. The colonial government would then respond by sending colonial forces to counter the Indian attacks. Sending out the troops is an expensive thing to do regardless if it’s in 2014 to counter non-state soldiers dedicated to establishing a religious-based political entity encompassing several countries in the Middle East (ISIL -Islamic State of Syria and the Levant).[34] Or by sending militias to protect the border against Indian attacks. Indians, by the way, were being supported by the French.

Berkeley was not opposed to fighting Indians who were considered enemies, but attacking friendly Indians, he thought, could lead to what everyone wanted to avoid: a war with “all the Indians against us.”[35] Berkeley also didn’t trust Bacon’s intentions, believing that the upstart’s true aim was to stir up trouble among settlers, who were already discontent with the colony’s government. Bacon attracted a large following who, like him, wanted to kill or drive out every Indian in Virginia. In 1675, when Berkeley denied Bacon a commission (the authority to lead soldiers), Bacon took it upon himself to lead his followers in a crusade against the “enemy.” They marched to a fort held by a friendly tribe, the Occaneechees, and convinced them to capture warriors from an unfriendly tribe.[36]

The Governor said he would no longer send in the troops and so Bacon’s attack was a challenge to Berkeley’s new policy. And Berkeley would not budge. So, Bacon disengaged marched on Jamestown and the Governor fled, with some of his supporters. Both sides promised freedom to slaves if they would join their side’s cause.[37] Then in Jamestown there was looting, burning, a general uprising among poorer whites and self-proclaimed free slaves. The uprising came to an end when two things happened: first, Parliament paid for an invasion force. The British army, in conjunction with the remaining elements of the Virginia militia, regained control of Jamestown and its surroundings and arrested Bacon, other leaders, and some of the white and black looters. The second thing that happened was the sudden death of Nathaniel Bacon, possibly of dysentery, the next month.

Indentured servants were necessary due to the labor needs of commercial tobacco farming. Indentured servants had gotten to be too expensive and too risky. So Berkeley discontinued the indentured servant program. No longer would any indentured servants be allowed to be brought into Virginia.

However, the reality of commercial tobacco farming is the need for labor, thus Governor Berkeley allowed for the unrestricted importation of African slaves. And where Virginia went, other colonies followed. The significance of Bacon’s rebellion was that it marked the end of indentured servants and the massive influx of African slaves, not just in Virginia but in the border colonies and the deep south.

Source: https://www.1619brooklyn.com/our-impact

Conclusion

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, European colonies in the Americas were limited to a few outposts in modern-day Florida, a few Catholic missionaries in the southwest, and extensive fishing along the Atlantic seaboard (especially for cod). By 1700 French-controlled Canada and the upper Midwest, Spain had increased its colonies in the Americas, and England had created 14 colonies, 13 of which were successful from Virginia in 1607 to Pennsylvania in 1682. By 1700 over a quarter of a million Europeans and Africans resided in the Americas and through the Colombian Exchange they transformed the land. Indian societies were, at best disrupted (such as the Powhatan), or at worst wiped off the face of the earth (such as the Taino). The Spanish, and to a lesser extent the French, created colonies of inclusion: Spanish settlers and Indians living together. The English colonies tended to be exclusionary and thus endemic warfare between the English and Indians marked the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. And that exclusion, by 1700, began to include an exclusion from the English government and to a lesser degree, the official Church of England. English colonists were slowly becoming “Americans,” they were just not aware of how similar they were. Not until an international crisis throws them together, not until the Yankee candle maker sleeps, eats, and fights side by side with that Georgia yeoman will they realize that they have more in common than they thought and that they have more in common than they had with the British. Next, the Seven Years War, the creation of “Americans” and a burgeoning “us versus them” mentality.

I would like to thank Alejandra Cantu, Sarea Crouch, Devin Dembley, Luis Gonzalez, Rory Harris, and Thomas Hudson who, in the Fall of 2019, analyzed Catherine Clinton’s Plantation Mistress. They performed admirably.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies. Please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Rodney King said this in 1992 in a press conference during some riots that resuted from the plce who were video tapped beating him up were not found guilty. ↵

- http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/halooing-huzzahing-roistering-seven-outlaw-christmas-celebrations/ ↵

- http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/winter07/jamestownside.cfm ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- http://www.ushistory.org/us/2f.asp ↵

- This passage is by Alejandra Cantu, Sarea Crouch, Devin Dembley, Luis Gonzalez, Rory Harris and Thomas Hudson. ↵

- Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982), eISBN 978-0-307-77248-0, page 24. ↵

- Ibid., 21. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 23. ↵

- http://www.crf-usa.org/foundations-of-our-constitution/mayflower-compact-text.html ↵

- http://www.gwirf.org/roger-williams-rhode-island-birthplace-of-religious-freedom/ ↵

- http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=3918 ↵

- http://www.usahistory.info/southern/Maryland.html ↵

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/magazine/2017/07-08/know-nothings-and-nativism/ ↵

- http://www.ourgeorgiahistory.com/history101/gahistory03.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- https://www.geni.com/projects/Anglo-Dutch-Wars-1652-54-1665-67-1672-74-1780-84/11989 ↵

- https://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h564.html ↵

- For example, under “President Donald Trump finally admits that ‘fake news’ just means news he doesn’t like,” see “Dear Donald Trump: Negative Coverage Doesn’t Mean ‘Fake’ News,” at https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/5/9/17335306/trump-tweet-twitter-latest-fake-news-credentials at viewed 22 Dec 18 ↵

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1M8YYSTznKU ↵

- https://www.upi.com/Archives/1983/10/06/President-Reagan-Thursday-saluted-freedom-of-the-press-as/8468434260800/ ↵

- http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/01/mary-fisher-quaker.html ↵

- http://www.onlinebiographies.info/gov/winthrop-john.htm ↵

- https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/07/selma-people-who-died_n_6810430.html ↵

- http://web.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/speccoll/quakersandslavery/commentary/people/woolman.php ↵

- https://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/870 ↵

- https://quizlet.com/143553901/the-middle-chesapeake-and-southern-colonies-flash-cards/ ↵

- Ibid. and https://www.apstudynotes.org/us-history/topics/the-middle-chesapeake-and-southern-colonies/ ↵

- http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/pa-history/1681-1776.html ↵

- https://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h545.html ↵

- http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h545.html ↵

- https://quizlet.com/221867842/social-studies-flash-cards/ ↵

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/11/300000-an-hour-the-cost-of-fighting-isis/382649/ ↵

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p274.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p274.html ↵