35 1970’s Pop Culture I: Blaxploitation, Disco, and Martial Arts

Jim Ross-Nazzal

WIP: For example, we are adding analysis on gender polemics and female empowerment in Blaxploitation movies. Need to add Fred Williamson, intersectional feminism, and more on horror films, to name a few.

I. The Intersection of Blaxploitation, Disco, and Martial Arts: Experiences of a Young kid from the Midwest

Like every other chapter, I do not presume to cover everything -just primarily things that are of interest to me and my students. And this chapter is not a comprehensive look at the 1970s This chapter is a result of a series of lectures that really piqued the interests of my students. The lectures were, in large measure, pertaining to aspects of 1970s pop culture that I was particularly interested in (not including Dungeons and Dragons, which I was introduced to in 1979) as I grew up in Wisconsin in the 1970s. In 1970 I was 6 and watched a lot of Captain Kangaroo. I do not remember my first Blacksploitation movie, probably not until the late 70s and it was either Blackula or Blackenstein. We saw a lot of monster movies at the drive-in and I do remember Blacksploitation movies by the later 1970s. Martial Arts intrigued me. My brother Pete and I played “Two Guys From ‘Nam.” And besides our rifles, we both had martial arts skills. We practiced our version of martial arts with our neighbor friends, and our action figures all had martial arts skills. And when I saw Staying Alive at the drive-in, I became enamored with disco. It was the beat. I was a drummer. The beat was driving. Simple, but brought the drums to the center stage.

Disco was cross-generational. Finally, we reached a point in the class, the 1970s, in which my younger students could see their parents’ experiences and my Gen X students could relive their youth. Students commented that disco was not just the music of their parents’ high school years, but that they still played it today (but now on Google’s Alexa not, on LPs) and then some went further and were able to identify some of the beats or parts of those older songs in current rap songs (sampling) and house music.

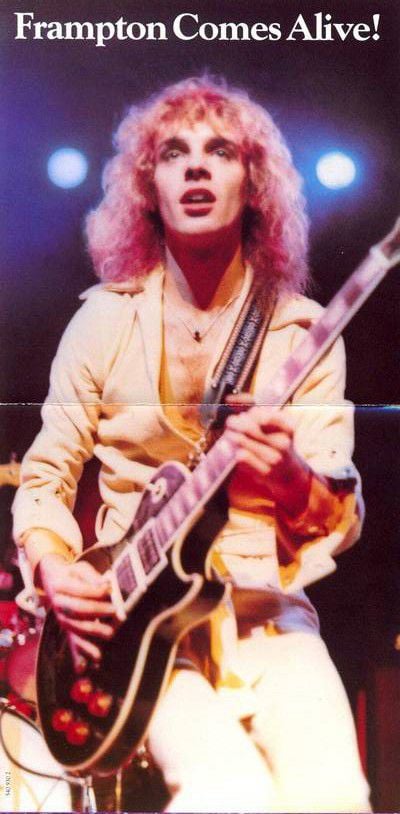

Martial Arts were also hot, hot, hot in the 1970s. We played with our G.I. Joes with the Kung-Fu grip and listened (only semi-seriously) to Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting.” And then there the movies, which we saw at the drive-in. Usually three movies on a Saturday night. The first movie was something silly (like the latest B-monster movie), then the blockbuster Summer hit (like Jaws or Saturday Night Fever), and the third movie was sometimes one of those Blacksploitation films, probably starring Fred Williamson or Pam Grier. Studying the 70s really made my students come alive, kind of like Peter Frampton in 1976.

A. Disco

Disco was a beat, a type of music, ways of dancing, and a culture. The beat of 1960s music pre-disco was the heartbeat, the Mowtown beat. High hat on 2 and 4 and the bass drum on the downbeat, making a “heartbeat” sound. Da, da-da; da, da-da. In the 1970s, the disco beat was four on the floor. Bass drum on 1 2 3 4. Also known as the Philly Soul sound. Created by The Trammps drummer Earl Young and best explained by him:

When I was a budding teenager, I listened to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, some Big Band stuff. I was neutral on disco, until 1978 when two things happened. First, I saw Saturday Night Fever (the preeminent disco movie) at the drive-in, and, I started high school and I was one of the drummers in the school’s band. I remember most of the trumpet section and this one junior drummer (a white guy with a perm) all hated disco. Our musical director was a younger guy. Seemingly fresh out of college. Mr. Mark Kleckley. A fantastic teacher. Taught me more about drumming in specific and music in general in my short time there than in all my music lessons in all the years before and after. Anyhow, Mr. Kleckley was Black in a nearly all-white school and he had the band play the contemporary hits, which tended to be disco: KC and the Sunshine Band, The Trammps, Bee Gees, Earth Wind and Fire, ABBA, for example. I loved the drum parts to those songs. Driving stuff. Like a train. And the beat controlled the song. Anyhow, I secretively learned to like disco. And when I hear “September” today, I am transported back to that Homecoming parade in 1978 with the marching band playing that song, and my first girlfriend, Cheryl cheering on. Anyhow . . .

Disco had specific dances that went along with the songs, such as the Hustle. Interestingly enough, the Hustle started as a dance popularized at various NYC clubs such as Studio 54, Adam’s Apple, and Adonis. Studio 54 was infamous. Anything and everything took place at Studio 54. Part Garden of Eden, Part City of Gomorrah, and all disco. The most Vs of Hollywood’s VIPs danced the night away with regular folks. Side by side. They engaged in other activities as well. Anyhow, a songwriter named Charlie Kipps saw the dance at Adam’s Apple and talked to his writing partner, Van McCoy. McCoy then penned the song “[Do] The Hustle,” which became a #1 hit on Billboard. So, while dances were created to go along with songs (such as the Dolphin, the Funky Chicken, and probably the most well-known as popularized by John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever -the Proud Mary), the song The Hustle was written to go along with the dance the Hustle.

The ultimate disco movie of the 1970s was probably Saturday Night Fever. The movie’s central character is Tony Manero (John Travolta). While he works in a hardware store, his life is dancing at the local club, 2001 Odyssey. Tony and an older woman with exceptional skills win the big dance contest, but Tony thinks the Puerto Rican couple should have won, but due to racism, they were not awarded the first place trophy. The movie is not just a fantastic soundtrack by the Bee Gees, and other popular contemporary artists. There is racism, gang violence sexual violence, suicidal ideation, and a death that may have been a suicide. Pretty hard stuff. But those themes are opposing the upbeat music. This is the Bee Gees “You Should Be Dancing” with Tony (Travolta) giving a dance workshop:

The ultimate disco group of the 1970s might have been the Bee Gees. Launched in 1958, the Brothers Gibb, Maurice, Barry, and Robin wrote their own songs and had numerous local hits in England and Australia in the 1960s. The group waned in popularity in the early 1970s. Played a string of second-tier British clubs (Sheffield Fiesta, the Golder Garter, and Batley Variety famously known to be ‘’where all the has-beens went to play’’) and then hit on the disco craze with Barry’s falsetto singing. Falsetto, while popular in the 1950s, had come back in semi-popularity in the 1970s. Producer Robert Stigwood took the Bee Gees under his wing, and Saturday Night Fever became the Bee Gees rise to the international limelight.[1]

Not everyone liked disco, as my story above suggested. Hatred of disco peaked in 1979 when a Chicago DJ decided to blow up some disco albums between baseball games one summer evening. It did not go well. Jacqueline Rios looked at that event.

This essay will scrutinize the Disco Demolition Night event that occurred during the late 1970s. An event to promote major league baseball quickly turned into a treat and riot against artists of color and homosexuals. It is important to begin with knowing that Disco started up as a counterculture that challenged society’s norms. This is because this music genre allowed people of color and homosexuals to feel welcomed and express themselves openly through music. In addition, Disco nightclubs in Philadelphia and New York City, for example, would allow any partygoer regardless of gender, ethnicity, age, or sexual orientation to attend because they believed in being all-inclusive. The majority of these Disco artists were Black and Brown people who wore attire that was colorful, expressive, and flamboyant. These disco artists had no shame in their game and felt they should be able to express themselves freely. However, this bothered many individuals who were homophobic and racist. On the 12th day of July in 1979, around seventy thousand prejudiced individuals flooded the baseball field to put an end to disco.[2] It must be pointed out that the maximum capacity of Comiskey park during the 1970s was roughly forty-seven thousand. The Comiskey Park was adjacent to Bridgeport, a neighborhood where the White residents made it known they disliked people of color.[3] DJ Steve Dahl, an American Radio Personality, was the person who arranged and hosted Disco Demolition Night. He advertised that the entrance fee to get in was 98 cents if you brought Disco records with you to throw away and destroy. Furthermore, everyone would throw the Disco records into a dumpster and light them on fire as a publicity stunt which was seen as a warning to many artists of color and gays. They did this because they wanted others to join them in the anti-Disco movement and make people of color feel inferior.

Vince Lawrence, an usher at Comiskey park baseball stadium realized that they were not just trashing Disco records but anything that Black music artists had made.[4] This is when the event got even uglier. Dahl’s army rushed to the field where the game was taking place, and it got so out of control that the ushers there could not do their job anymore – police now had to get involved. It now was becoming a riot where these individuals were chatting disco sucks and broadcasting hate. Lawrence mentions an experience he had where a white man snaps a 12-inch record in half in front of his face.[5] He comes to the conclusion that it was directed to people of color hence the amount of only black artist records from different genres in the dumpster and his own encounter being there as a Black usher at the event. Dahl mentions that there was no intention of the event discriminating against people of color. However, there was not any person of color destroying black artist music. In conclusion, this event should have not occurred since White men were blatantly trying to destroy music from Black and Brown artists, the majority of who were women, and end a genre that was accepting towards gays. No one should feel afraid of simply existing because of their skin color and who they are.

B. Martial Arts

Martial Arts were all the rage in the 1970s and toys were not immune to the gravitational pull of the trend, such as G.I. Joe.

GI Joe is an American action figure created in 1964 by Hasbro. There were four members to the GI Joe team, each representing a branch of the US military: Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force. From the National Toy Hall of Fame: “Joe established his success in the first year as millions of boys found him a compelling toy for imaginative play. The action figure’s popularity rose steadily until American involvement in Vietnam made war-related toys less appealing. Hasbro responded with a new Joe. The soldier of 1964 became a Land Adventurer in 1970 and took on more peaceful action, recovering lost mummies and rescuing the environment.”[6]

Then from Popular Mechanics 4/9/2019: “In 1970, G.I. Joe was restyled once again and the line was renamed G.I. Joe Adventure Team. Joe was still a tree-hugging world traveler, but now he had lifelike hair, eyes that could shift from side to side, and Kung-Fu Grip, which allowed him to actually hold his weapons and grip ropes to climb a mountain or swing from a tree. Pictured on the packaging, illustrations inspired rescue raft or flying missions, firefighting, and even encouraged kids to seek out the abominable snowman.”[7]

Articles on GI Joe’s Kung Fu grip in Time, Popular Mechanics, and the Official Hasbro website, emphasize the toy’s ability to hold weapons and other objects for the first time. However, my examining the G Joe commercial introducing the Kung Fu grip, we see Hasbro focused on a different aspect of the innovation.

Commercial: The commercial begins with two men in white outfits with black belts, bowing to each other, then engaged in some sort of martial arts. One throws the other to the ground. The two boys are playing with their Joes as the announcer describes the new feature -the Kung Fu grip. “And here is G.I. Joe with Kung Fu grip. G.I. Joe has hands that grip. Fingers you hold open and let closed. Hands that hold on with a Kung Fu grip. The grip that you help Joe use in self-defense.” And that’s the interesting part of the commercial/feature. The martial arts feature is not for offensive, aggression, or attacking but rather for defensive purposes only. This suggests the new role of G.I. Joe -Joe the adventurer, the spy, the guy who saves endangered white tigers. An innovation for safeguarding and preservation of life, liberty, and the American way? A bit close to Superman’s tagline. This commercial for G.I. Joe with the Kung Fu grip came out in 1974:

Then there was Kar-A-A-Ate Men by Aurora. The game came out in 1975. This game seems to be based on the popular boxing game Rock’ Em Sock’ Em Robots. Both Karate Men, dressed in white martial arts outfits with black belts, are fixed to their own blue base. The Karate Men are jointed in several locations along the arms, legs, and torso. Each base has 3 control buttons to move both arms and kick with one of their legs. One arm chops, and one arm punches. The winner can knock their opponent over with a punch or kick to the chest plate. Here is a commercial for Aurora Karate Men Action Figures:

The Big Jim action figure from Mattel included a martial arts outfit. The pirate adventure set called Fighting Furies by Matchbox (1974-1975) released the “Kung Fu Warrior Adventure.” Finally, the G.I. Joe knock-off, Action Jackson (by Mego Corporation, 1971-1974) included a martial arts outfit. When we were kids, my brother Pete and I had Action Jackson action figures. In 1976, we buried the figures, vehicles, clothes, and objects in the area under which my parents had a new garage built (everything was covered by the cement floor). Now I see on eBay how much this stuff is going for and I am rather mad with my 12-year-old self.

Pop music could not even dodge the martial arts craze. Carl Douglas, a singer-songwriter from Jamaica, had a Gold record (sold at least 1 million copies) in 1974 with the song “Kung Fu Fighting.” For the week the song was released the single hit #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100, #1 on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles, and #3 on Billboard’s Hot Disco Singles. For the year, “Kung Fu Fighting” ended up at #14.

In 1977, Heart (Ann and Nancy Wilson) had a top 10 hit with Crazy on You. Playing live on The Midnight Special, the guitar player Roger Fisher wore a Gi (pronounced ghee). He sported a tan belt. There is no tan belt in karate, judo, taekwondo, jujitsu, or any other type of martial arts that I can fiend either now or in the 1970s. Except, the US Marine Corp has a martial arts program and their initial belt is tan. The Marine martial arts program was established in 2002. So, maybe he was wearing the tan belt for decoration purposes only. Still, wearing a gi demonstrates the popularity of martial arts and the intersection of martial arts and music at that time.

Martial arts were on television in the 1970s. One of the more popular shows was called Kung Fu. The show was a new take on the old westerns. Instead of the sheriff or cowboys who wear the white hats, the good guy was a traveling Shaolin monk named Kwai Chang Caine. The bad guys were the racists and racism he ran into in his travels. Cain’s father was Caucasian and his mother was Chinese. Caine grew up in China but killed a relative of the Emperor and so he fled to the United States when a bounty was put on his head. He seeks two things: 1) peace; and, 2) his half-brother, Danny Caine. The show takes place during Reconstruction (1870s).

“On the week ending May 6, 1973, Kung Fu became the number one show on US television, drawing a regular audience of 28 million viewers. Around the same time, Bruce Lee’s Hollywood debut Enter the Dragon was being completed.[25] It was part of what became known as the “chopsocky” or “kung fu craze” after Hong Kong martial arts films such as Five Fingers of Death (King Boxer) and Bruce Lee’s Fists of Fury (The Big Boss) topped the US box office in early 1973.”[8]

Caine faces racism in every episode and he does so with silent calmness, only using his martial arts skills in defense of himself or others. For example, when he is attacked, repeatedly, in a bar. Caine had just crossed the desert and he entered this bar seeking water. The bartender did not charge him. “Water is free,” said the bartender. And Caine stood at the end of the bar quietly drinking his mug of water when a fellow patron launches into a racist tirade and tries to take it out on Caine. You will not hear language like this on broadcast television today.

Exercise had been on the rise since Jack LaLanne’s first television show in the 1950s. By the 1970s, running began to take on popularity due to runners such as Jim Ryun and Jim Fixx, but in the 1960s Eastern culture (religion, philosophy, music) entered the American youth culture and so by the early 1970s, martial arts, as self-defense and exercise, was hot. Popular martial artists included Bruce Lee and an up-and-comer, Chuck Norris:

There were strictly martial arts movies in the 1970s, not to be confused with movies that included martial arts to advance the storyline. In the 1970s, martial arts movies from China and Hong Kong saturated the American market, starting with Fists of Fury, Enter the Dragon, and Five Fingers of Death. These movies made Bruce Lee a star in the US, although he was already well known in Hong Kong and China. Lee’s pupil, Jim Kelly, also starred in some of those movies. The American movie industry magazine Variety coined the phrase “chopsocky” to describe those types of films. “Chop” from the food chop suey and “sock” from another name to punch. Chopsocky. Chopsocky films are not what I am talking about in this chapter as chopsocky films were inherently foreign in nature. Introduced to the American market. While this is another example of the intersection of martial arts and American pop culture in the 1970s, chopsocky films tended to be divorced from disco and Blacksploitation. Chopsocky was a genre in and of itself, in other words.

Chopsocky films were inherently different then from what follows.

C. Blaxploitation

Movies that highlighted the talents of Black (“Black is Beautiful,” “Black Power”) actors, directors, writers, and others but with the tendency of promoting violence, drugs, misogyny, and other negative stereotypes coupled with the heavy beat of disco (plus some funk) and plenty of martial arts, is Blaxploitation movies. Some are serious social commentaries with plenty of gender polemics, but many of those movies are silly, over-the-top, gangsters, cops-and-robbers, the “soul brother” against “the man,” 90-some-minute movies that fit the drive-in model of the 1970s. Well, if you scratch below the surface, you can see some serious themes of these movies. According to Loryn Lamonte,[9] Blaxploitation at first glance shows very stereotypical caricatures of black culture; however, when you look deeper into the movement it becomes clear that blaxploitation taught people to be unapologetically black. Blaxploitation encouraged black consumers to embrace the culture and beauty standards that white people vilified and ostracized over generations. Wearing their hair in a confident way, wearing colorful suits, and reconnecting with black culture by reclaiming historical pieces of fashion was a large, but tacit way for designers for the blaxploitation genre to show power in their films.[10] “It also manifested the fashion, language, mannerisms, and swagger of the blaxploitation characters. Black men became soul brothers. Their afros, platform shoes, leather jackets, loud jewelry, hip handshakes, and use of expressions like “righteous,” “groovy,” “fly,” and “dig it” were representative of soul and, thus, blackness.”[11]

Lamonte continued, the villains created in many of these films were often white law enforcement officers. White people were almost always the villain in these films, and often the women villains were white lesbians to contrast the hypersexualized black female protagonists, who were heterosexual. Many criticisms against blaxploitation films were the characterizations of black protagonists. Protagonist heroes often dabbled in drugs, copious amounts of sex, and normalized violence, and other crimes like prostitution. “Blaxploitation films have allowed Black characters to reclaim their sexuality- their femininity and masculinity. Importantly, these films allowed Black actors to take a leading role instead of taking the role of the antagonist or the “other” in the film.”[12] Many consumers were outraged with the depictions and glorification of violent black stereotypes. The often one noted, “anti-heroes” were hated by black founded organizations like the NAACP, who collaborated with other organizations against Blaxploitation to end the genre in the latter half of the 1970s. While the films were more diverse by adding queer characters, many queer people were uncomfortable with the language hurled at the characters in the films. Derogatory and homophobic remarks towards the queer characters enraged the queer community and was another reason why the support for the end of the genre was so popular.[13]

One thing these movies had in common was the intersection of stereotypes, disco, and martial arts.

From the website viddy-well.com:

“The blaxploitation genre is a subset of exploitation cinema, which is fundamentally comprised of independently produced, low-budget B-movies or grindhouse films. These films typically revolve around lewd, violent or taboo subject matter, and are engineered specifically to attract an audience through sensation and controversy.”[14]

“Blaxploitation films featured black actors in lead roles, and typically centered around African Americans overcoming oppressive, antagonistic and generally white authority figures, referred to as none other than “The Man.” More often than not, protagonists in blaxploitation films were outlined as stereotypical characterizations, such as pimps, pushers, prostitutes, or bounty hunters, but at their core, promoted a message of black empowerment.”[15]

“The term “blaxploitation” was coined by Junius Griffin, the then-head of the Los Angeles National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in the early 70s as a criticism for the less-than-positive images of African Americans depicted in the genre, and his influence would later contribute to its demise. However, not everyone in the black community agreed with the NAACP’s assessment.”[16]

“Despite the genre’s potential to reinforce negative stereotypes, a large majority of the black community considered blaxploitation cinema to be a sign of progress. Before the genre’s birth in 1971, the typical depiction of African Americans in television and film was as sidekick or victim; however, the dawn of this new cinematic movement would seek to put an end to that.”[17]

Marquita Smith in Afro Thunder writes, “Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970)—credited as the first Blaxploitation film—set out a framework of inner-city plot themes and stereotypical characterizations that subsequent films followed. Blaxploitation films generally feature a black hero or heroine who is socially and politically conscious, possessing the ability to ‘survive in and navigate the establishment while maintaining their blackness.’ The lead characters are surrounded by a black supporting cast and white people are often portrayed as villains who ‘feel the wrath of black justice.’ Novotny Lawrence writes that the heroes and heroines are in control of their sexuality and ‘dictate the circumstances of their erotic encounters’ as a testament to their independence.[18] This may hold true for the male leads but the sexuality of the female leads is marked by an illusion of control because of the overarching patriarchal system they must navigate.[19]

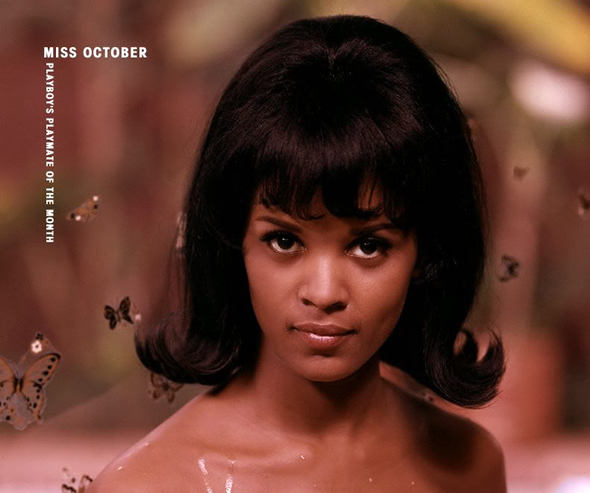

There were several actors who gained fame during this era, one being Jeannie Bell. Bell was a near-native Houstonian (being born in St. Louis but grew up in Houston). She graduated from Texas State University in Houston’s historic Fourth Ward. She was the first African American woman to be in the Miss Texas pageant. I believe that was in 1966. And, Bell was the second African American centerfold in Playboy (October 1969). She married Gary Judis, the couple had one son and now lives in Los Angeles. In 2020, at the age of 76, she set a Guinness world record for continuous jumping rope for septuagenarians.[20] Besides exercise (“I also want to motivate people to get out there and walk or jump rope five minutes a day”), Bell is an artist and an illustrator for children’s books. “[P]ainting is my passion,” she recently said.[21]

Bell “admitted that she’s ‘really blessed and happy,’ and as well as thankful for a range of memorable experiences in her life such as working as a Playboy bunny, being featured on the cover of Jet magazine and becoming the second Black woman to appear as the Playboy centerfold. She also dated the actor, Richard Burton.”

‘I lived with Richard in Switzerland for a while and he wanted to get married, but I didn’t want to marry an alcoholic because I do not drink,’ said Bell. ‘But, he was a nice guy, so I got him get sober and return to his ex-wife, Elizabeth Taylor.’ “Columnist Earl Wilson noted [Bell’s] success with “drying out” Burton in the Syracuse Herald-Journal in September 1975.”

“I worked with a lot of interesting people and they were all good to me. I had a lot of fun,” said Bell, who acted in several movies including “Trouble Man” (1973), “The Klansman” (1974), “Three The Hard Way” (1974), “TNT Jackson” (1975), and “The Choirboys” (1977). Her television credits encompass several episodes on “The Beverly Hillbillies” as well as “Sanford and Son” (1973), “That’s My Mama” (1974), “Kolchak: The Night Stalker” (1975), “Baretta” (1976), and “Starsky and Hutch” (1977).”[22]

The following is about the Blacksploitation Movie TNT Jackson:[23]

TNT Jackson is a 1974 American film about a young woman, a karate expert, who goes to Hong Kong to search for the killer of her brother. TNT Jackson in the film is the name of the young karate black belt, a woman with a strong and incredible personality, who is always confident and determined to get whatever she wants. On her mission to Hong Kong, she gets embroiled in a gang war as she crosses the United States border. Blaxploitation is a motion picture genre that was popular in the early 1970s. The genre was subjected to criticism as rife and inferior following its denigrating stereotypes. However, the women of Blaxploitation are perceived to have changed the view of blaxploitation, through films made by these heroines, including TNT Jackson.

TNT Jackson combines analyses of the contexts and histories that were shaped by these heroines through a feminist theory, which can be traced back to the achievements of the black actresses of the time within the United States. Further, TNT Jackson served as an illustration of the racism and burden of representation that the Blaxploitation faced in Hollywood women, especially the discrimination subjected to the female actresses since inception. All along, the careers of black actresses have been shaped through the lines of stereotypical conceptions concerning women, which were illustrated by other films including Jezebel, Sapphire, and Aunt Jemima, alongside other 19th century films such as Gone with the Wind and Imitation, filmed in the 1930s and 1940s.[24] The films helped illustrate the challenges of women actresses across different facades.

The movie was a big trial to reach the standards of top-performing film in the blaxploitation genre, for example, Foxy Brown. In this attempt, TNT Jackson did not manage to reach this height since creating a compelling character to meet the standards of such a big film corporation was hard. Further, the main actress of the TNT Jackson, Jean Bell, did not have the same presence as the one who depicts Foxy.[25] As hard as she tried to pretend to be tough, she never came to be that way. She did not have compelling actions to make a viewer feel that she was a karate woman, considering that she never moved in fight scenes.

Another big problem with the film was the fact that, despite being a kung fu movie, TNT Jackson was characterized by gunfights. The film was based on a gang dealing with dangerous and illegal activities, therefore questioning the type and synopsis of the movie. The blaxploitation genre would expect people to fail to question such issues, which would be risky as this is not always the case. Further, there was no action seen during the fights as the people involved could pretend to be hitting each other, yet a viewer could see that they are not. Such actions made the movie look miserable, and this could have been corrected by doing appropriate editing to come up with a better output.

Additionally, the other actors of the movie appeared mixed-up and disorganized, a key characteristic of low-budget films. However, some actors were good in their roles and displayed quality jobs. For example, Stan Shaw, according to Picou, was a charming, arrogant, and sleazy fellow, characterized by more schemes that were hard for one to realize.[26] He left a desirable job, which was a near perfection performance.

The movie is an American film that sought to address the issue of racial discrimination in the USA, but black women were not granted equal opportunities in Hollywood, therefore, leading to the poor quality of the film. TNT Jackson was made based on very poor editing decisions, which led to the presentation of unrealistic videos.

Probably the most well-known, hardest-working Blacksploitation-era actor was Pam Grier.[27] For a dissertation on the intersection of Pam Grier and feminism, see Theresa Campbell’s Blaxploitation as an Apparatus for Female Empowerment: How Pam Grier’s Films Redefined Notions of Gender and race.

Pam Grier, a pop star, action movie star, and a forerunner amongst black and female representation to not only African-American audiences but all of Hollywood. At 70, she is a cancer survivor, feminist advocate, and is quietly retreating from the spotlight in rural Colorado. After the decline in the genre of Blaxploitation in Hollywood, Grier somewhat struggled to keep her fame. Throughout the height of her career, however, she also tackled opposition from the African-American community for her projections of stereotypes of black people in her movies. Grier, encouraged by Hollywood and most new outlets, spoke out about her take on her past, the height of her career, and her influence on the perception of black, female actors.[28]

In an interview with Tell Me More with NPC News, Grier was asked what her take was on the outrage voiced by the black community. She answered by voicing that her goal had primarily been to have more female lead roles in movies. She also reminded viewers that there had been a few movies before hers were debuted, but “they weren’t called Blaxploitation, not until a woman did it and I had stepped into the roles of the shoes of a man. Now it’s Blaxploitation because here’s a woman posturing as a man, laughing and joking and being powerful and strong like a man. And all of a sudden there’s an issue. Well, to me, it wasn’t an issue. To me, it was letting our community see what was going on.”[29] Her objective was to reveal and address the problems of black communities, rather than sweep them under the rug.

Julia Watterson looked at black women in 20th-century pop culture, specifically, “the evolution of the ‘angry black woman’ stereotype. As I will demonstrate, black women were portrayed as caretakers then aggressive, loud, and rude in the media, creating a stereotype that evolved throughout the 20th-century.”

“Before the angry black woman stereotype, the media created the mammy stereotype.[30] A “mammy” was a black woman who would take care of white people, for example, in the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, and the film Gone with the Wind, a black woman’s role was to take care of a white family.[31] These racist stereotypes existed to justify or ignore slavery and other crimes against black women.[32]”

“The original “angry black woman” in pop culture was a character named Sapphire on the TV show “Amos ‘n’ Andy”.[33] Sapphire was a black woman framed as rude and aggressive, unable to handle her rage, especially to her husband.[34] Before the 1951 TV show, “Amos ‘n’ Andy” started as a radio show in 1928 with predominantly white voice actors mocking and exaggerating black behavior.[35] After Sapphire the character was off the air, the Sapphire image was used in other media as a stereotype.[36] For example, in 1972, Aunt Esther from Sanford and Son was another angry black woman character in a comedy TV show.[37] Aunt Esther would call the main character, a black man, names and insult him while also dominating her black husband, a weak character.[38]”

“In 1974, the TV show Good Times incorporated the Sapphire character into a family living below the poverty line.[39] Thelma, the sister was a sapphire character, and her role was to harass her brother.[40] The neighbor, Willona Woods, was also a clear sapphire but focused her insults on the other black men in the show.[41] J.J., the brother was a character called a “coon caricature” which was an anti-black stereotype of black men portrayed as dumb and useless.[42] The racist portrayal of a black male was often accompanying a racist stereotype of a black woman and vice versa, since the sapphire character had a role to berate and focus anger towards “useless” and “incompetent” black men.[43] Other pop-culture appearances of sapphires include The Jeffersons,1975, and in 1992, Martin.[44]“

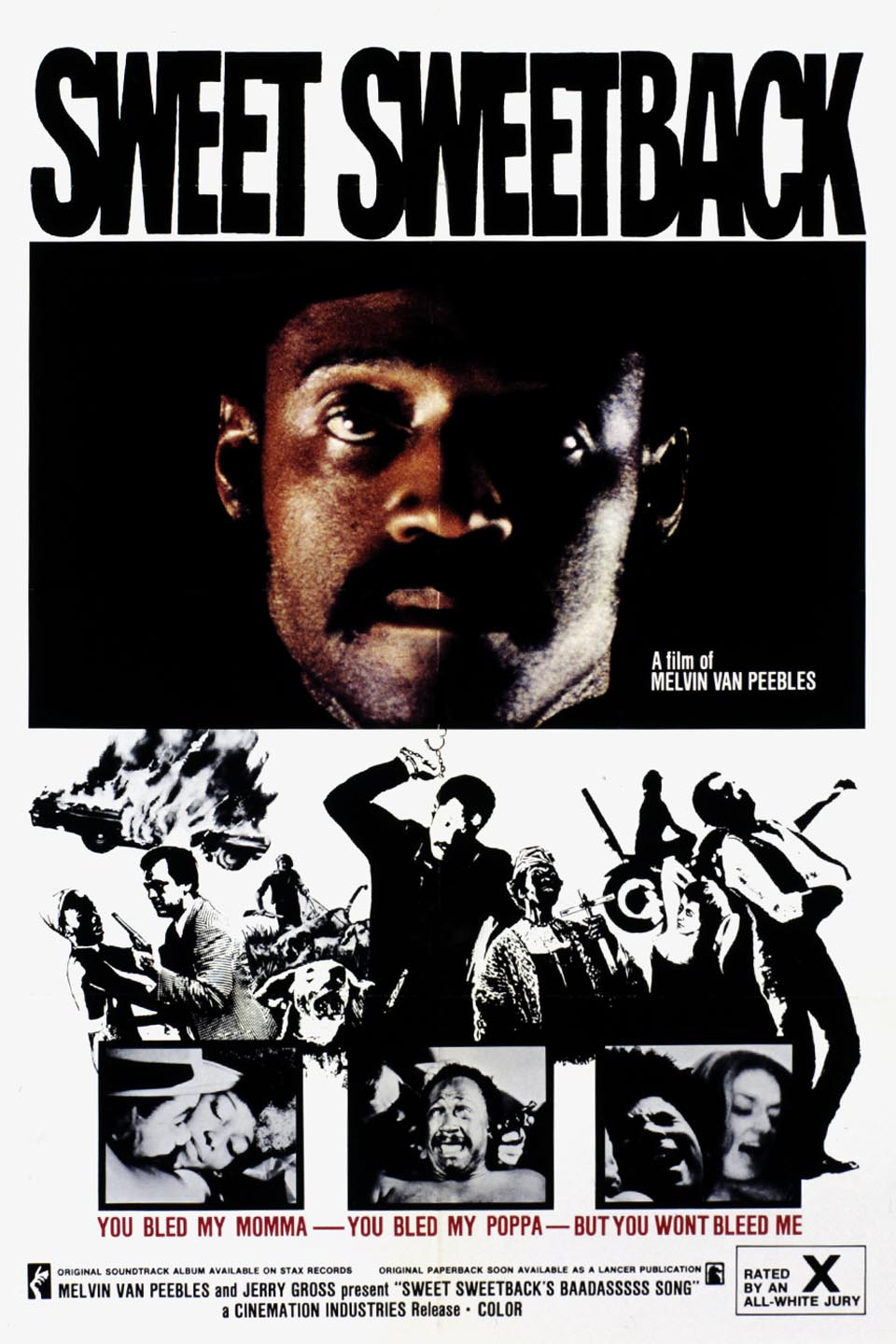

“The “Blaxploitation” era shows the black criminal stereotype that was prominent in media after the emergence of the sapphire character.[45] Movies like Shaft, Superfly, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, and The Mack, with huge, almost cult-like followings were labeled black exploitation movies or “Blaxploitation.”[46] Other examples of blaxploitation were Cleopatra Jones, Coffy and Foxy Brown.[47] These three movies included black women in the role of the Jezebel stereotype.[48] The Jezebel was a woman who held all her power through her sexy body and “whore” tendencies.[49] This stereotype commodified black woman’s bodies and dehumanized them, which is a practice used since slavery to justify treating black women as less than and ignore any complexities they have.[50] In conclusion, the 20th-century pop culture showed black women with stereotypical traits like aggression, uncontrolled anger, rage, and crime to portray the sapphire caricature or blaxploitation. While these caricatures are no longer the only portrayal of black women in media, the impact lives on in racist stereotypes and tropes today.”

In an article of Vulture, Grier is put on a god-like pedestal; the article proclaiming “that the mere act of being Pam Grier is a performance.” The articles continue to portray her as brash and outspoken, but admirable as well. Recalling her past, asking about any regrets, and revealing the current state of her career and in turn, her happiness, the article finishes off with a taste of Grier’s true personality and ideal, positively representing women.[51] Newspapers and interviews depict Grier as a confident woman who’s had a fairly satisfying and successful career and continue to engage in moderately large roles in movie productions and in the public eye. It seems that at the edge of retirement, news outlets reminiscently repeat her influential legacy upon pop culture and perceptions of the black community.

Why does the media constantly recite Grier’s story? One theory could be that in a time of rising liberalism and feminism, the standard principles and values of Grier are being echoed all over America. In the era of Time’s Up and #MeToo, Grier can relate to the struggles of being a woman. In the times of segregation and controversy amongst races colliding, Grier can narrate her own experience as an African-American in the 1970s. Her personal recount of history in relation to African-Americans and women gaining rights and respect is being heard and revered by the public.[52] And so, as it’s the media’s sole purpose, the interests of the people are being acknowledged and reported on, allowing legends like Grier to be in the spotlight again, with a more modern aspect towards it.

From Marquita Smith in Afro Thunder![53]

Coffy, directed and written by white filmmaker Jack Hill, was among the earliest Blaxploitation films to have a female heroine. During the film’s director’s commentary, Hill credits his knowledge of black culture to his time spent as a youth hanging out with musicians in black sections of Los Angeles. He also offers that the actors in the film contributed to its development. In the 1973 film, Pam Grier stars as Coffy, a nurse who takes the law into her own hands to seek revenge for her younger sister’s heroin addiction by posing as a Jamaican prostitute to infiltrate the underground drug ring. In the opening scene, the viewer is introduced to Coffy in her role as a seductress. She poses as a drug-addicted prostitute who will “do anything” for a fix and the drug dealer does not refuse her. Once in the drug dealer’s home, Coffy appears in command as she coyly reveals a breast while asking the dealer to turn off the light. Before he realizes what is about to happen Coffy shoots him at close range with a shotgun. Before leaving, she forces another drug dealer to overdose by injecting himself with heroin. This scene sets the tone for the rest of the film as Coffy uses sex as a method of luring her unsuspecting targets.

By adhering to the historical sex object archetype of black women in film, Coffy’s construction as a sex object subverts her role as a powerful action heroine. Her utilization of sexuality as a trap is successful because she appears to be subservient to the domineering power of a patriarchal set of ideals and assumptions concerning the role of women. In her day-to-day life, Coffy does not have a solid grasp of her situation. She is having trouble focusing at work and feels helpless in her fight to heal her sister and fight the rampant drug abuse in her community. Her relationship with Councilman Howard Brunswick allows for some insight into the complex sexual relationship between a black man and woman. He introduces Coffy as a “liberated woman” to his white associate in public then later refers to her as a “lusty, young bitch” after having sex. The power and honor he bestowed on her just hours before is stripped away as he reduces her to a mere sex object. Her belittlement continues in her everyday life as a random white man approaches her car outside of her job and inexplicably attempts to fondle her. Her police officer friend Carter comes to her rescue. Later, when Carter’s apartment is ambushed, one of the attackers attempts to assault her (again exposing her breasts) before fleeing the scene. In the director’s commentary, Hill states that beautiful actresses are “not afraid to show [their bodies]” and that Grier believed it was something she was “expected and proud to do.” Stephane Dunn details the implications of Grier’s bare breasts as she writes that the film perpetuates “the historical white supremacist construct of black women as ‘sluts’ and ‘prostitutes’ who are ‘objects of open sexual lust.’ Camera shots throughout, including those of the male gazes directed at Grier within the films, reveal the objectification of her ‘black’ sexualized body” (111). However, this construct also extends to the black men who are active participants in Coffy’s hypersexualization. The frequent acts of sexual violence and aggression directed at Coffy and her subdued responses greatly imply a numbing complacency with such harassment.

The objectifying of the female body continues to move the film’s plot forward from Coffy’s everyday life into her alternate role in the drug underworld. After obtaining information on the main drug supplier for her community—Arturo Vitroni—Coffy adopts the persona of “Mystique,” a Jamaican prostitute, to get closer to him. She first attempts to penetrate his circle via a pimp/dealer named King George. When she introduces herself to George he rationalizes his objectifying desire to have sex with her by saying he has to “test her out” for Vitroni. She offers her body as a means to gain access to Vitroni. Later, “Mystique” gets into a fight with George’s call girls at a party and uses her curly hair as a place to conceal weapons. Hill credits Grier with incorporating this idea into the film and says she got it from what was “really happening,” referring to the techniques some African-American women used for protection. This aspect of the film furthers its correlation to the armed militant women aligned with the BPP. As mentioned, the BPP’s militant stance championed the use of weapons for self-defense.

Vitroni, aroused by the woman-on-woman violence, calls her a “wild animal” that he has to have. Once Coffy obtains access to Vitroni for a sexual encounter he spits on her, calls her a “no-good dirty nigger bitch” and screams at her, demanding that she crawl. When Coffy points her gun at him, he quickly dismisses her visible threat. He does not consider her as a formidable enemy and thinks George has sent her to kill him, an idea to which Coffy acquiesces. To Vitroni, the idea of a black woman cunningly plotting to kill him is beyond belief or comprehension. Coffy’s plan is foiled as she is captured, beaten, and locked in a shed by Vitroni’s men. When she is confronted with the truth of Brunswick’s involvement in the drug ring in the presence of Vitroni, Brunswick publicly denigrates her saying “she’s just some broad I fuck” and suggests that she be killed. After making her escape and returning to confront Brunswick, Coffy is visibly swayed by his rhetoric. She is unable to overcome her emotion and kill him as she has done other men encountered in the course of her mission. Her only impetus to harm him comes when she sees that he has a naked white woman upstairs, triggering her to shoot him in the groin. Her sexuality repeatedly used to lure in her enemies, functions as a double-edged sword as it also makes her vulnerable to the man she cares for. By the film’s end, Coffy’s role as a powerful woman in command is undercut by her near-fatal inability to make decisions independent of the manipulation of a man who has demonstrated blatant disregard for her as a woman and as a human being. Her inspiration to act stems more from personal retribution than from ideals of saving her community or women’s liberation.

Grier and others have responded to the criticisms of the Blaxploitation genre. Speaking of her roles within the genre, Grier says:

[My films] reflected the black community through language and music. We basically documented what was going on… musically, religiously, and politically. I appreciate that…now because now we can look back and see what we were about, and what we were saying. In the ‘70s we reaped the rewards of the ‘50s and ‘60s… It was a time of freedom and women saying that they needed empowerment. There was more empowerment and self-discovery than any other decade than I can remember. All across the country, a lot of women were Foxy Brown and Coffy… I just happened to be the first one that these filmmakers …found to portray that image.[54]

Smith concluded, “Grier, a self-described feminist, has acknowledged the dilemma between her characters on film and the message she had hoped to portray. Her sexy image bothered her. In the Ms. interview, Grier blames AIP for fostering her image so “all you see is bang, bang, bang, shoot ‘em up tits and ass.”[55] Yet, Grier continued to make films with AIP while planning to strike out on her own with a production company. She was a “bankable” star; as long as the money was coming in, the relationship between Grier and AIP was a tolerable one for both parties. During the course of a New York Magazine interview, Grier asked the writer if “down there” (referring to the peep show and sex shop area of 42nd street in New York City) was were her films really made money.[56] The interviewer described Grier as being visibly uncomfortable with the implication of being viewed as a sex object more than she was appreciated as an actress. When the Blaxploitation genre faded out, so did Grier’s star power. The demise of the Blaxploitation genre came about because of Hollywood’s shift of perception towards the end of 1973. Hollywood’s belief that black audiences were tiring of the redundant storylines and the realization that an all-black movie was not necessary to draw in a black audience rendered Blaxploitation films obsolete.[57] Consequently, Grier’s number of leading roles all but disappeared. Since her decline in stardom, Grier has lived a relatively quiet life. In 1997, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino—a self-proclaimed fan of Blaxploitation films—selected Grier for her first leading role in years for Jackie Brown, in many ways an homage to the defunct genre. Jackie Brown gave new life to Grier’s acting career and she recently had a role on the Showtime television series “The L Word.”[58]

“Despite various shortcomings and constant criticism, the Blaxploitation genre does provide a source of cultural value to the black community and American popular culture at large. During its height of popularity, the genre provided an opportunity for African-Americans to make money in the film industry. One notable cultural contribution comes in the form of soundtracks from the films, which match the plot themes or—as in the case of the soundtrack for Superfly (1972) written by soul artist Curtis Mayfield—challenged them. While Superfly glorifies the storyline of a flashy drug dealer, the message in Mayfield’s music paradoxically speaks of the dangers and consequences of drug abuse.”[59] I would say there are other examples of Blaxploitation movies that provided opportunities for African American musicians, such as Shaft! (1971).

Speaking of Shaft, John Shaft was a private investigator who refused to follow the rules. He was violent; killing frequently. As Lucey Gagner points out, the main characteristics or stereotypes of black men in movies such as Shaft, Super Fly, and Sweet Sweetback’s Badaaaas Song, were “hypersexual, hypermasculine, criminal, and violent.” Shaft, specifically, demonstrated characteristics such as hypersexuality, aggression, and violence [60] Sweetback is a sex worker who fights “the man.” Sex is a running theme throughout the film. In the opening credits read “This film is dedicated to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the man.” And according to Melvin Van Peeples, the screenwriter, director, and star of the film, the “film tells the story of a ‘bad nigger’ who challenges the oppressive white system and wins, thus articulating the main feature of the Blaxploitation formula.”[61]

According to Lucey Gagner, a past student from Trinity University:

According to Lucey Gagner, a past student from Trinity University:

Shaft was an industry-backed filmed. The result of this was the creation of John Shaft, a private detective who operates in his own space, sleeping with women of both races,

talking back to white cops, and fighting black gangsters when necessary. While John Shaft embodies the sexual, aggressive, hyper-masculine image of the badass black man, he does not embody any of the black power rhetoric found in the badass black man figure of Sweetback. “Blacks in these new films are no more than thematic templates reworked with black casts and updated stereotypes that reconfirm white expectations of blacks and serve to repress and delay the awakening of any real political consciousness” (Guerrero, 1993: 93). This is important because it shows how the shift from independently produced blaxploitation films to industry-produced blaxploitation films worked to hide the politics behind the influence of the Black Panther Party, instead promoting individualistic and stereotypical images of black men.[62]

Other sources for gender and Blaxploitation are Iconography of the Black Female Revolutionary, and Heroines, Honey, and Hos.

Then there was Jim Kelly. Kelly was one of several students of Bruce Lee. Kelly played roles in a variety of martial arts films such as Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon. Kelly’s first lead role was in the film Blackbelt Jones. Mariam Joseph, one of my students from the Summer of 2021 looked at that movie:

The film industry has always experienced a gradual growth from the moment the first film was directed in 1888. “This growth has been brought up by the demand to create a film that will satisfy the diverse market. Some of the early films were focused on the genres romance, drama and action movies, with the rest comedy, drama, fantasy, thriller and horror following later.”[63] Black belt Jones is an example of an early film that received a lot of attention during its early periods and its popularity has slightly diminished to date. Black belt Jones is an interesting ethnic subgenre of exploitation film of martial art. The film Black Belt Jones was directed by Robert Clause in 1974. The highlight of the film is a land deal that was supposed to be possessed due to unpaid debts. Papa Byrd Karate school is situated in the land and thus Black Belt Jones has to be called in for assistance.

“The three actors that assumed starring roles are Gloria Hendry, Scatman Crothers, and Jim Kelly. Hendry is the lady whose dad had passed on with a debt that belonged to the mafia. On getting that news, she declined to let loose the building that was hosted in the land. Crothers is the person that owned the Karate dojo; an institution that trains student martial arts. Kelly is a martial artist that gets hired during retaliatory attacks and he is the person referred to as Black Belt Jones.”[64] The three actors mentioned above play a significant role that shapes the theme of the film. After its release, the film created sufficient buzz thus attracting all forms of criticism.

“Reviews from viewers that were sampled by independent internet sites such as rotten tomatoes reveals that the film is above the standard. The film gets an average of three and a half stars from the fifteen reviews made by viewers.”[65] The film is considered to portray some outstanding martial arts that made some compare it with Bruce Lee. Sentiments from one of the reviewers are that “Black Belt Jones is the best Blaxploitation that has been produced to date.”[66] Black Belt Jones has influenced the theme of most of the films that are currently on the screens.

Black Belt Jones came as a relief because it is produced at a time when there is a demand to introduce other genres of films. “The film is Blaxploitation in nature with a total screen time of approximately eighty-seven minutes; a time that is standard for most films. The film utilizes people that are more likely to be considered “as own” especially if watched by African-American.”[67] At least ninety percent of the actors in the film are of the African-American ethnicity. This is seen as a step towards African-Americans involvement in films that are widely recognized and accepted.

The film can be rated as a general; suitable for family view, though the violent scenes might not be suitable for persons below the age of sixteen years. Black Belt Jones scores a seven out of ten because of its originality and storyline. The ratings can increase if the film reduces the number of violent scenes as distributed across the film. The storyline is easy to comprehend since it is a common cause of conflict across the U.S.

Blaxploitation seeped into monster movies. Monster movies were popular in the 1970s. Think Jaws and The Exorcist. One Blaxploitation monster movie was the intersection of black stereotyping and Dracula: Blacula.

Tylar Johnson, a student of mine in the Summer of 2021, looked at the 1972 movie Blacula:

On one hand, the genre was initially seen (hoped for) as progressive as African American actors took prominence in front of the cameras. On the other hand, many of the movies being directed by white filmmakers resulted in the movies being saturated with negative and offensive stereotypes. The release of Blacula in 1972 was one of the trailblazers for black horror films because it allowed a black man to be a different type of protagonist challenging the issues of racism, while also allowing a prominent level of black involvement in its creation. This film helped to pave the way for African American self-identity, and representation in a white-dominated film industry.

Black films preceding Blacula’s release in 1972 all followed much of the same theme.[68] The black actors were usually cast as drug dealers or gang members defeating white antagonists (“The Man”), and the women were usually prostitutes or promiscuous women, all being directed by white filmmakers. Many African Americans were supportive of them because of the opportunity black actors got by being cast in leading roles, despite the intense stereotypes that were consistently flaunted. Blacula was one of the first films of its kind and offered not only leading roles for black actors but also promoted black creation and artistry on the developmental aspect of the film. The movie was directed by William Crane, an up-and-coming African American director, who cast William Marshall to play Blacula. The movie still contained stereotypical themes, such as being depicted as a primal, monstrous creature, but the film’s importance is recognized for its political standings that are narrated.[69] The film touched on aspects and ideals of The Black Panther Party, which was founded in 1966 to advocate for armed self-defense as protection from police brutality.[70] Many black film critics shared that it was empowering to see Blacula fight off police officers, highlighting the brutality issue that was happening in Los Angeles, California. Another important feature of Blacula was Crain’s casting of female characters. In previous black films, women were usually house cleaners, or promiscuous women/prostitutes. The women in Blacula were always career-minded women with jobs such as a photographer, pathologist, and taxicab driver. This was one of the first times that women were depicted as something other than promiscuity.

Even though it emerged during an era of a struggle for representation, Blacula is arguably one of the most important films that were released during the wave of Blaxploitation movies. William Crain’s insistence on black inclusion of both men and women in all aspects of the film’s development helped to spotlight black talent and pave the way for many black actors and actresses to come in future films.

Thank you to my students Julia Watterson, Ny Ny Doan, Iqra Yamin, Jacqueline Rios, Siyuan Zhao, Oluwakemi Sanni, Mariam Joseph, Tylar Johnson, and Julie Arrez. Their interests, dedication, and hard work only made this chapter more interesting.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Paul Stokes, “6 Ways DISCO Changed the World,” BBC (BBC), accessed July 30, 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/23hgH64c0cvLlwYjfmzcztJ/6-ways-disco-changed-the-world. ↵

- Frank, Gillian. "Discophobia: Antigay Prejudice and the 1979 Backlash against Disco." https://www.jstor.org/stable/30114235?seq=1 Last Accessed May 2, 2021. ↵

- Alexis Petridis, “Disco Demolition: The Night They Tried to Crush Black Music,” https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jul/19/disco-demolition-the-night-they-tried-to-crush-black-music, 1. Last Accessed May 2, 2021. ↵

- Alexis Petridis, “Disco Demolition: The Night They Tried to Crush Black Music,” https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jul/19/disco-demolition-the-night-they-tried-to-crush-black-music, 1. Last Accessed May 2, 2021. ↵

- Alexis Petridis, “Disco Demolition: The Night They Tried to Crush Black Music,” https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jul/19/disco-demolition-the-night-they-tried-to-crush-black-music, 1. Last Accessed May 2, 2021. ↵

- https://www.toyhalloffame.org/toys/gi-joe ↵

- https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/a25994500/gi-joe-history/ ↵

- Wikipedia page for Kung Fu. Originally Desser, David (2002). "The Kung Fu Craze: Hong Kong Cinema's First American Reception". In Fu, Poshek; Desser, David (eds.). The Cinema of Hong Kong: History, Arts, Identity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–43. ISBN 978-0-521-77602-8. ↵

- Loryn Lamonte, HCC student, Summer 2021, Excerpt from piece on Blaxploitation. ↵

- Cedric J. Robinson. “Blaxploitation and the Misrepresentation of Liberation.” Race & Class 40, no. 1 (July 1998): 1–12. Accessed August 1, 2021. ↵

- Joshua K. Wright. “Black Outlaws and the Struggle for Empowerment in Blaxploitation Cinema” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 2, no. 2 (2014): 63-86. Accessed July 30, 2021. Pg. 67 ↵

- Angelique Harris, Omar Mushtaq. “Creating Racial Identities Through Film: A Queer and Gendered Analysis of Blaxploitation Films” Social and Cultural Sciences Faculty Research and Publications. 248. Accessed July 31, 2021. Pg. 32. ↵

- Joshua K. Wright. “Black Outlaws and the Struggle for Empowerment in Blaxploitation Cinema” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 2, no. 2 (2014): 63-86. Accessed July 30, 2021. ↵

- https://www.viddy-well.com/articles/the-history-of-blaxploitation-cinema ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Lawrence, Novotny. Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s: Blackness and Genre. New York: Routledge, 2008. ↵

- Afro Thunder! Sexual Politics and Gender Inequity in the Liberation Struggles of the Black Militant Woman. Marquita R. Smith vol. 22, no. 1, Fall 2008-Spring 2009 Issue title: Politics and Performativity ↵

- https://lasentinel.net/multi-talented-jean-bell-judis-still-blazing-trails-at-76.html ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Researched and written by Ny Ny Doan in the Fall of 2019. ↵

- Courtney Bates, “A Closer Look,” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 37, no. 1 (2007): 111. ↵

- Charleston Picou, “Film Review: TNT Jackson (1974)”. HorrorNews.net, 2019, https://horrornews.net/142527/film-review-tnt-jackson-1974/ ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Researched and written by Iqra Yamin, Fall 2019. ↵

- John Carucci, “As Pam Grier Celebrates 70, She Finds Peace off the Grid,” go (Paddock Publications, July 20, 2019), https://go-gale-com.libaccess.hccs.edu/ps/i.do?p=STND&u=txshracd2512&id=GALE|A594199656&v=2.1&it=r&sid=ebsco) ↵

- Allison Keyes, “Pam Grier Looks Back In New Book,” go (National Public Radio, Inc. (NPR), May 18, 2010), https://go-gale-com.libaccess.hccs.edu/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=txshracd2512&id=GALE|A226657996&v=2.1&it=r&sid=ebsco) ↵

- Ellen E. Jones, “From Mammy to Ma: Hollywood’s Favourite Racist Stereotype,” BBC, May 31, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190530-rom-mammy-to-ma-hollywoods-favourite-racist-stereotype. Accessed April 1, 2022. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Mayowa Ania, “Harnessing The Power Of 'The Angry Black Woman,” NPR, February 24, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/02/24/689925868/harnessing-the-power-of-the-angry-black-woman. Accessed April 8, 2022. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- David Pilgrim. “The Sapphire Caricature,” Ferris State University, August 2008. https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/antiblack/sapphire.htm. Accessed April 5, 2022. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Tre’vell Anderson, “A Look Back at the Blaxploitation Era Through 2018 Eyes,” Los Angeles Times, June 8, 2018. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-ca-mn-blaxploitation-superfly-20180608-story.html. Accessed April 8, 2022. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Kovie Biakolo, “Mammy, Jezebel and Sapphire: Stereotyping Black Women in Media,” Aljazeera, July 26, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/program/the-listening-post/2020/7/26/mammy-jezebel-and-sapphire-stereotyping-black-women-in-media. Accessed April 2, 2022. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Jason Bailey, “Pam Grier on Orgasms in Your 60s, Jackie Brown, and What's Next,” go (New York Media, November 1, 2018), https://go-gale-com.libaccess.hccs.edu/ps/i.do?p=ITOF&u=txshracd2512&id=GALE|A560723547&v=2.1&it=r&sid=ebsco) ↵

- John Carucci, “As Pam Grier Celebrates 70, She Finds Peace off the Grid,” go (Paddock Publications, July 20, 2019), https://go-gale-com.libaccess.hccs.edu/ps/i.do?p=STND&u=txshracd2512&id=GALE|A594199656&v=2.1&it=r&sid=ebsco) ↵

- https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=mfsfront;c=mfs;c=mfsfront;idno=ark5583.0022.104;g=mfsg;rgn=main;view=text;xc=1 ↵

- Lawrence. Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s. p. 91. ↵

- Kincaid, Jamaica. "Pam Grier: The Mocha Mogul of Hollywood." Ms. Magazine. August 1975: 49-53. ↵

- Jacobson, Mark. "Sex Goddess of the Seventies." New York Magazine. 19 May 1975: 43-45. ↵

- Guerrero, Ed. Framing Blackness: African American Image in Film. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993, p. 105. ↵

- Smith. Afro Thunder! http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.ark5583.0022.104 ↵

- Smith, Marquita. Afro Thunder! ↵

- Gagner, Lucey, "He's a Complicated Man": Representations of black masculinity in Blaxploitation Films." Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2016. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/592. ↵

- Ibid., p. 36. ↵

- Ibid, and see Guerrero, Ed. 1993. Framing Blackness: The African American Image In Film. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ↵

- Barry K. Grant, Film Genre Reader IV. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012, pp 8-10 ↵

- Robert Clouse, Black Belt Jones. DVD. Warner Bros: Amazon.com, 1974. ↵

- Rottentomatoes. "Black Belt Jones Reviews". Www.Rottentomatoes.com.2012 (last accessed 12 Jul 2021) ↵

- Ibid ↵

- William W Falk., and Bruce H. Rankin. "The Cost of Being Black In The Black Belt". Social Problems 39 (3):1992, 299-313. DOI: 10.2307/3096964. ↵

- Wright, Joshua K. "Black Outlaws and the Struggle for Empowerment in Blaxploitation Cinema." Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 2, no. 2 (2014): 63-86. Accessed July 30, 2021. doi:10.2979/spectrum.2.2.63. ↵

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: The Rise of Black Power, pg 1004 ↵

- Benshoff, Harry M. "Blaxploitation Horror Films: Generic Reappropriation or Reinscription?" Cinema Journal 39, no. 2 (2000): 31-50. Accessed July 31, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225551. ↵