9 American War for Independence

1776-1783

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

“Our army manned the air, it rammed the ramparts, it took over the airports, it did everything it had to do, and at Fort McHenry, under the rockets’ red glare, it had nothing but victory. And when dawn came, their star-spangled banner waved defiant.”[1]

-Donald Trump, July 4th, 2019, praising American efforts during the War for Independence

Americans used to belief in sacrificing for the greater good. Participation in war and in support of war peaked with World War II. Ever since, people have worked to or openly avoided having to go to war and those on the home front tend not be as engaged in American military efforts as Americans had been engaged since before 1945. Without sounding like that old man shouting at those kids to “get off of my lawn,” Americans ideas on liberty today include the belief in not having to sacrifice. That had not always been the case. What follows in an essay on “sacrifice” during the run-up to the War for Independence, researched and written by Rebekah Hankins, a student in one of my classes on US History to 1877, Fall of 2019.

Colonists before the Revolution all pledged allegiance to the king and integral parts of colonial culture originated in Britain, such as the social importance of drinking tea.

Even though Britain was the mother country to the colonies, Parliament imposed several injustices upon them. One injustice was Britain’s actions regarding trials and how people were tried for crimes depending on the individual. After Parliament’s passing of the Sugar Act in 1764, colonists accused of smuggling molasses were to be tried without juries.[2]

Colonists who were alleged smugglers would no longer experience the same justice process that native Britons were still able to experience, that being a trial by jury. Additionally, when Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774, one of the acts included was the Administration of Justice Act which declared that if a royal official was accused of a crime while they were in Massachusetts, their trial would take place in Britain instead of using a jury in the colonies.[3] This showed legislative favoritism for native Britons and royal officials over the colonists.

Colonists began to resist the injustices imposed by Britain. Merchants stopped importing British goods in port cities to push for the repeal of the Stamp Act. The Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty were two groups that influenced the resistance by leading their communities. The Sons of Liberty were advocates of nonimportation in order to repeal the Stamp Act. The Daughters of Liberty resisted against the Townshend Act of 1767 by not using certain products which were taxed by the British and instead grew and made items that they needed. The colonists in resistance did not stand to take the injustices from Britain. Resisters knew there was more in store for the colonies than tolerating the acts from Britain.

Colonists went through great challenges during the Revolution and the War for Independence with an uncertain future on the other side of hardships. The War for Independence left soldiers without resources and 2,500 Americans died from disease in 1777-1778. This left many women home and widowed, having to now provide for their family.[4] Americans hoped for freedom on the other side of the Revolution so much so that they endured diseases, war, and dramatic hardships to secure independence.

The War: An Abridged Edition

In 1776 there were small skirmishes, indecisive battles but no catastrophic losses. Only small ones. Small victories in New York versus the Hessians and then Princeton in January of 1777 when Washington crossed the Delaware into New Jersey and surprised a British force of around 1,400 men. Alexander Hamilton led an artillery battery during the battle. This and other victories led the British to withdraw from southern New Jersey and a jump in morale among Americans, which led to a rise in volunteers the following spring.[5]

British strengths included a larger population (approximately 7.5 million versus 2.5 million colonists), wealth, naval forces, and a professional army with about 50,000 British troops, 30,000 Hessian troops, and 30,000 Loyalists in the colonies. British weaknesses included unrest in Ireland so their military and wealth were split, the British government was generally inept and confused. Britain did not enjoy a unified desire to crush the Americans. Whigs cheered American victories, for example. Their generals were weak, officers treated their troops brutally at the slightest infraction of law or regulation. The better officers were off fighting in Ireland. Their provisions were inadequate, they were fighting an offensive war, and the territory was difficult to subdue because it was so vast.

American strengths included effective leaders such as George Washington, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and foreign military experts who came to side with the Americans such as the Polish general Thaddeus Kosciusko, and the Marquis de Lafayette from France. The Americans were fighting a defensive war and fighting for their literal homes. They enjoyed a self-sustaining agricultural base and much shorter resupply lines. Americans were better marksmen and embraced the moral goal of protecting British liberties, freedoms, culture and history for the world. Things that England had turned its back on.

American weaknesses included a badly organized and disjointed military. While the Continental Congress openly debated a myriad of issues, they rarely acted upon those debates and provided little political leadership. The government compact (Articles of Confederation) was not written until five years into the war and states wanted to most protect their claims to their borders over neighboring states’ claims. They had little valuable currency -limited gold and silver that could be minted so they printed and distributed what became worthless paper money, which led to inflation, which led to increased prices, which led to a barter system, which led to some governments (such as Massachusetts) requiring people to pay their taxes in gold or silver coins. Finally, the Americans had inadequate arms and ammunition, clothing (especially shoes) was scare and profiteers weakened American resolve.

The British strategy was to control the cities with the help of their navy; cut the colonies in half, arouse Loyalist participation thus quickly ending the war. Spoiler Alert: didn’t happen. The British failed because General William Howe first tried to conquer Philadelphia before heading south and got bog downed and never met up with his counter parts. Then General John Burgoyne marched south from Canada but never gained the Loyalist supporters he had planned for. He did get the attention of American snipers who took potshots at his troops all along the way and was defeated at Saratoga. The British finally enter the southern colonies in 1780. They took Charleston, which included 5,000 American troops and a loss of 4 ships. Charleston was the costliest American defeat. But the Americans did not have too long to lick their wounds because in the Fall of 1781 General Charles Cornwallis, surrounded by French and American troops, surrenders at Yorktown. Peace negotiations turn serious in 1782 and in 1783 the British officially recognized American independence, US territory was set at the Mississippi River and from Canada to Florida, individuals and states had to pay debts to England, and the Mississippi River would be open for both British and American shipping. Those were some of the aspects of the Treaty of Paris. That same year, Americans learned about their two-year-old government under the Articles of Confederation.

Major battles of the War included

Lexington-Concord April of 1775 First armed conflict and a moral victory for the Americans

Bunker Hill June 1775 1/6th of British officers killed during the entire War died at that battle. First and last major siege of Boston

Trenton Dec 1776 Washington crushed Hessian troops

Saratoga Oct 1777 Convinced French of US strength and send 5800 men to join the American efforts.

According to Fnu Zabihullah[6], “the British commander Burgoyne led his soldiers from Canada toward New York’s lake. In the opposing side, the American commander General Horatio Gates controlled northern New York. When the battle started, the British Army moved too far into New York which made it harder for their soldiers to get food and supplies from Canada. The American army took advantage of their weak point and defeated them with high casualties. In the following year, another historical victory for the American was the official recognition of the independence by France and becoming a permanent alliance of the Americans.[7] [France] immediately started to support Americans with military supplies. Soon after that, Spain also joined France and both countries support Americans against British army.”[8]

Yorktown Oct 1781 British surrender.

The War and the Other

Women participated in every aspect of the war, to include in the military. Some joined on purpose while others, due to their situation, gained combat experience and, albeit it for a brief time, became honorary men.

Deborah Sampson

Several hundred women, dressed as men, enlisted in the Continental Army and state militias. One example of a women who enlisted was Deborah Sampson (1760-1827),. Sampson was born in Plympton, Massachusetts and was a descendant of an original colonists (Priscilla Mullins Alden). She joined the army in 1782 using the pseudonym Robert Shurtleff (she spelled her last name differently on various documents during her time in the Army) and enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment.

She was first wounded in battle near Terrytown, New York. Her wound possibly caused an infection which led to a fever. She was treated then released from military service. She received an honorary discharge in 1783. General Henry Knox signed her discharge papers. After the war, she received a one-lump payment pension from the state of Massachusetts. She spent the rest of her life traveling throughout New England, in her uniform, giving speeches on her experiences as a solider during the Revolution.

Mary Cochran Corbin

Cochran was an orphan at a young age. Her father was killed in an Indian raid and her mother was taken captive, never to be heard from again. Mary and her siblings were raised by an uncle. She ended her life as one of the most well-know and highly honored veterans of the War for Independence.

On November 16, 1776, Corbin dressed as a man and joined her husband in the Battle of Fort Washington on Manhattan Island. There, she helped him load his cannon, and when he was killed, she quickly and heroically took over firing the cannon against the British. Other soldiers commented on “Captain Molly’s” steady aim and sure-shot. Eventually, however, she, too, was hit by enemy fire, which nearly severed her left arm and severely wounded her jaw and left breast. She was unable to use her left arm for the rest of her life. The British eventually won this battle, with Corbin numbered among the prisoners of war who were paroled and released back to the care of Revolutionary hospitals.

Left to support herself alone, Corbin struggled financially. After she recovered, Corbin joined the Invalid Regiment at West Point, where she aided the wounded until she was formerly discharged in 1783. Then, on July 6, 1779, the Continental Congress, in recognition of her brave service, awarded her with a lifelong pension equivalent to half that of male combatants. Congress also gave her a suit of clothes to replace the ones ruined during the conflict.[11]

Nancy Morgan Hart

Hart was a spy for the Americans who routinely dressed as a man while she spied on the British. Her home was commandeered by six British soldiers, who neatly stacked their weapons in the corner of the house while Hart was forced to cook for them. Very quietly, Hart removed the weapons from the room while the men ate. Then she took one of the weapons and held the men at bay, until help could arrive. In the meantime, one of the British soldiers charged her. She fired and killed him. The rest were hung by the townspeople.

Mary Ludwig Hays

Women who gained combat experience because they took the place of a man who was injured or killed were given the nickname “Molly Pitcher.” That may have started with Hays whose nickname was Molly. Other historians argue that Molly Pitcher was the nickname for any woman who served or fought in the artillery and thus Hays may be fictional. Anyhow, during the war, she followed her husband into the Army performing the various roles of a camp follower. But her duties included providing pitchers of water to her husband and other men while engaged in combat as well as in camp. Hay’s husband was fell ill (possibly heat stroke) at the Battle of Monmouth in June of 1778. She took her husband’s place on the firing line. Her combat experience is murky at best. Some stories have her operating a cannon while others have her firing her husband’s musket. Her myth grew after the War, to include that her tenacity of purpose on the battlefield that day saved her unit from having to retreat. Her story is so convoluted that the year of her death is uncertain. And according to her legend, General George Washington made her a non commissioned officer (her rank is speculative) and thus earned the nickname Sergeant Molly. She received an annual pension from the state of Pennsylvania. According to the National Women’s History Museum:

Camp Followers

However, the clear majority of women who participated in the War were camp followers such as Martha Washington (wife of George) and Catherine Greene (wife of General Nathanael Greene). They provided food, dressed wounds, cleaned clothes, and provided comfort. Some camp followers were entrepreneurs who sold alcohol and other necessities to the troops and some were prostitutes. Due to women’s service during the War, women gained rights and opportunities following the war. For example, some women won the right to divorce and to own property. Women’s ability to become classically educated increased. However, these advances were sporadic and for the most part, after the Revolution, women were escorted back into their traditional roles of wife and mother. This process will be repeated until World War II.

The roles of camp followers have been down played, at best, or dismissed, at worst by historians. According to Holly A. Mayer in Belonging to the Army: Camp Followers and Community During the American Revolution:

First Peoples and the War

Native peoples fought for the same reasons as the Patriots: access to cheap and abundant land, the right to self-govern, and various ideas of liberty. One example was the Cherokee leader named Dragging Canoe. The Cherokee, while not officially an ally of the British when the War broke out, eventually allied with the British. They attacked American settlers and at least two American forts in North Carolina, for example, led by Dragging Canoe. Dragging Canoe led a contingent of approximately 700 men. Their success resulted in elements of the North Carolina militia having to engage the Cherokee. Cherokee lost major battles and soon they threw their support to the American side, but Dragging Canoe continued to fight against American encroachment. Those that Dragging Canoe led became known as the Chickamauga Cherokee and focused their attacks primarily against American settlements and settlers.[15] According to the many myths that Andrew Jackson spun about his backstory, he would recall that at the age of 11 he witnessed an alleged Cherokee attack on American settlers during the War.

Iroquois

England tried to get the Iroquois Confederacy to join on their side, so too the Americans. Although initially they remained neutral, eventually the Iroquois split with some joining the British side and some the American side, primarily the Oneida and Tuscarora. And within each tribe there were split allegiances. The Mohawk leader Joseph Brandt openly supported the British efforts. Brandt was educated by the British as a young man, eventually adopting all manifestations of British culture to include his name and religion. He translated parts of the Christian bible into his indigenous language and after the war became an evangelist among his people. Brandt’s sister, Molly was the wife of Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the British. Brandt died in 1807 and buried at the Episcopal church he helped build near Ontario Canada.

Africans and the War

Both free Africans and slaves fought for both the Americans and the British. The latter group being promised by both the American and the British governments to be awarded their freedom upon their side winning the War. The British created a military unit made up entirely of slaves (ex-slaves?). They were known as the Ethiopian regiment and they worse sashes and shirts that read “Liberty to Slaves.” Titue Cornelius, aka Colonel Tre, was an escaped slave who fought for England who was a guerrilla in New Jersey, leader of the “Black Brigade.” Upon his death, Colonel Stephen Blucke took command who supposedly fought at Yorktown.[16]

As negotiated in Paris, England was prohibited from removing “property” from American and that meant slaves. But the British were unwilling to hand over fellow soldiers. Soldiers who they had promised their freedom.

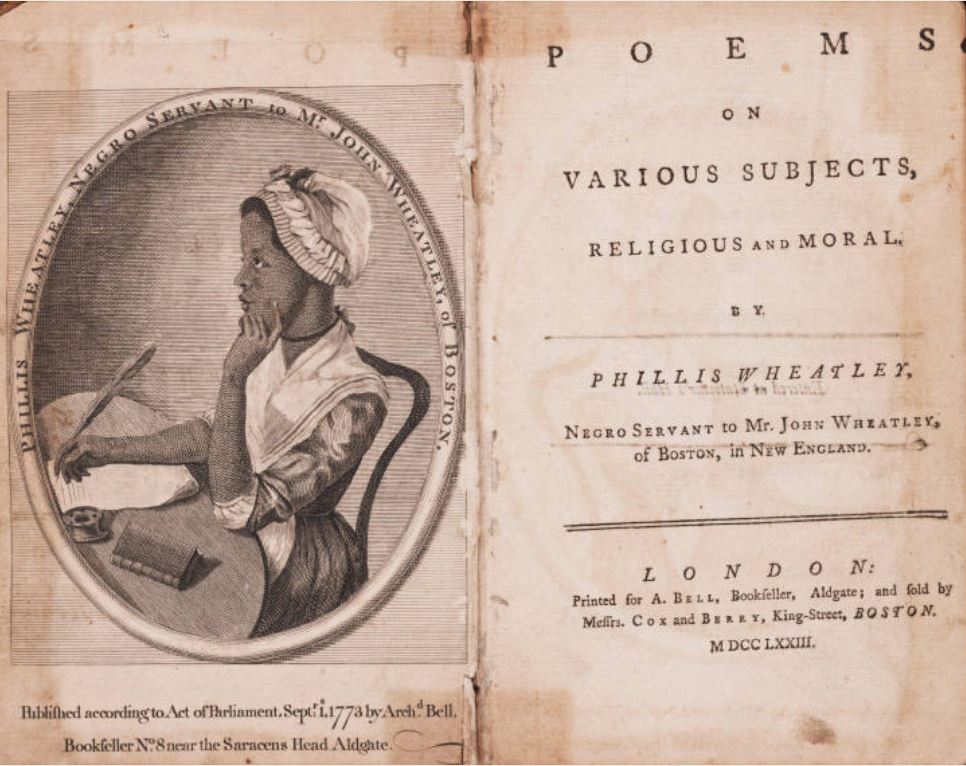

Phyllis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley was a slave who won her freedom in part due to the popularity of her poetry. She was sold into slavery at the age of seven by a wealthy Boston family who had her tutored in, among various disciplines such as history and astronomy, languages such as Greek and Latin. Two aspects of British culture most appealed to her: Christianity and British poets, such as Milton and Alexander Pope. Her initially popularity came upon the circulation of a poem about the popular Great Awakening preacher George Whitefield. Much of her poetry reflected her belief in the civilizing and salvation of Christianity, such as poem she presented to what is now called Harvard (known as the University of Cambridge at that time). She corresponded (and eventually met) George Washington and her supporters included two signers of the Declaration of Independence: John Hancock and Dr. Benjamin Rush. And, a slave-preacher from New York named Jupiter Hammon. Wheatley will eventually be given her freedom, possibly after much pressure upon the Wheatley family. Her poems also combined abolition with Christianity:

She often spoke in explicit biblical language designed to move church members to decisive action. For instance, these bold lines in her poetic eulogy to General David Wooster castigate patriots who confess Christianity yet oppress her people:

But how presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind

While yet o deed ungenerous they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric: blameless race

Let virtue reign and then accord our prayers

Be victory ours and generous freedom theirs.[18]

Marines and the War[19]

Early in the American Revolution, a key strategy of the Americans was to disrupt the effectiveness of the British by focusing on naval operations. On November 10, 1775, the 2nd Continental Congress proposed the creation of an amphibious fighting force to work alongside the newly created Continental Navy.[20] We currently know this force as the United States Marine Corps, but at their inception they were referred to as Continental Marines.

Following the end of the Seven Years War, Britain had accumulated an enormous amount of debt. The inevitable fight for American Independence began when the British parliament issued new laws and taxes in 1763, to help alleviate some of Britain’s debt.[21] However, the official start of the American Revolution did not take place until April 1775 at the Battle of Lexington and Concord.[22] Though the British Empire had immense power, as demonstrated by having control of nearly half of North America, supporting this war from the opposite side of the Atlantic Ocean was proving to be a challenging feat for Britain. The purpose of raising the Continental Navy was to intercept British maritime operations, who were fueling the troops at war, and to weaken the British economy by either destroying or capturing shipments. Out gunned and far outnumbered against the Royal Navy, the Continental Navy needed extra support during their naval engagements.[23] Less than a month after the creation of the Continental Navy, congress passed the Resolve of 10 November 1775, also called the Continental Marine Act of 1775, which began the recruitment of the Continental Marines.[24]

“The few, the proud, the Marines,” although this is the current recruiting slogan for the United States Marine Corps it was also an accurate depiction of the Marines when they were first established. Detailed within the new order from Congress, the number of Marines being recruited was significantly fewer compared to the other departments and totaled less than 1%. Their enlistment required experience as sailors so they could be useful for maritime operations, if needed.[25] Commissioned by Congress, local Philadelphian tavern managers and freemasons, Samuel Nicholas and Robert Mullan, were appointed as the first Marine Commandant and Captains of this new outfit.[26] Their establishments were immediately used for recruiting the two Continental Marine Battalions. Tun’s Tavern has always been recorded as the birthplace of the Marines, but since Captain Nicholas had been commissioned prior to Captain Mullan, historians argue that Conestoga Wagon was most likely the tavern used first.[27] Some operations were focused on the British West Indies, so not only were men recruited through the use of alcohol at the tavern, but with promises of adventure to the Bahamas and the high seas.

The intent of the Continental Marines was multipurpose. One of their first duties was to support the Continental Navy aboard vessels by acting as security guards. They would protect the Captain of the ship, help keep sailors in line as they perform their duties, and provide support during engagements by acting as sharpshooters on top of the ship’s masts. Also, as an amphibious force, they would assume the responsibility of conducting land raids ordered by the captain.[28]

The Marine Corps today still holds its tradition of performing world services in land, air, and sea. No other country or fighting force has ever conducted as many engagements on foreign territories as the Marines.[29] Having an amphibious force was not only necessary during the American Revolution, but continues to be crucial with the vast number of enemy target areas across the Eastern Seaboard and beyond. Since the creation of the Continental Marines and the United States Marine Corps, its existence and its purpose have been argued as to whether they are necessary. People have often wondered if their purpose could have been fulfilled by the standing army, but George Washington argued to Congress that implementing such a vast change would cause too much headache and extra troops could not be spared.[30] As history continues, the Marines faithfully prove their worth with the unique capability of being an amphibious fighting force.

Other Reformers and Reforms

During the Revolution, states as well as individuals supported the expansion of liberty. For example, New Jersey initially (and for short time only) allowed “all free inhabitants” to vote, which thus included free Africans and women. Abigail Adams pressed her husband John to extend liberties and freedoms to all citizens, including women.

Abigail Adams

“Remember the ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember, all men would by tyrants of they could . . . Emancipating all nations, you insist upon retaining absolute power over Wives . . . If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies, we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have to voice or Representation.” -Abigail Adams to John Adams, March of 1776, while he worked on drafting the Declaration of Independence.

Historians disagree if her famous demand ‘Remember the ladies” was about the relationship between government and the government or gender relations in families. Finally, Thomas Jefferson wrote a law that ended the English practice of government deciding how property or wealth would be distributed upon one’s death (known as entails). He drafted a bill that prohibited governments from supporting one religion over others, called for public (and free) education that would be paid for through taxation, a call to revise the penal code, and the gradual emancipation of slaves. Jefferson tried to end slavery three times in his life: 1) in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, in a proposal on how to govern the western territories (which eventually became known as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787) and manumission throughout Virginia. The ideas on education, the penal code, and emancipation were not adopted by the Virginia legislature, although Jefferson pressed those concepts throughout his life.

New Jersey and Accidental Woman Suffrage

The New Jersey constitution gave the right to vote to “all inhabitants of this colony, of full age, who are worth fifty pounds … and have resided within the county … for twelve months.” That included women and free Africans as well. But only single women could vote by 1790 because married women were prohibited from owning property. And by 1807, the New Jersey legislature limited suffrage to white men only. The Fifteenth Amendment (1870) will return the right to vote for African American men (universal male suffrage) and the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) will return women’s right to vote.

Economic Problems and Remedies

Inflation in the new country sky rocketed during the Revolution to the extent that paper money was worthless. Massive inflation led to both a depression and the development of bartering more often than the use of paper money. Although prices fell dramatically during the War (good for consumers) the effects on the farmers and producers was devastating. Unable to pay their taxes, the fledgling federal government was unable to pay its debts. Different states employed different responses to the national economic crisis. For example, New England states initiated protective tariffs (taxes on imports). Southern states eliminated the tariff in the hopes of attracting trade, then selling those imports to northerners for a handsome profit. Banks opposed to the use of anything but locally printed paper money. States enacted barter laws in order to provide relief to their farmers, and some states (such as Massachusetts) required that all debts, including taxes, be paid in specie: coins minted in gold and silver. However, most taxpayers (such as soldiers) were paid with worthless paper money and thus were unable to pay their taxes. Unable to pay their taxes, the state government began taking their land, which led to a group of veterans to raise arms against the state -Shay’s Rebellion. A good example of an interest group run amok, I guess.

Government

The various states offered different approaches to government and American people openly debated the form of a new national government. There were two main philosophies on government: one that believed that the best government is a local government (radically democratic) while the other argued for a strong, central government (conservative). “We must take mankind as they are, not as we wish them to be” was a sentiment circulated by those who supported a central government. While “The people best know their wants and necessities, and therefore are best able to govern themselves” encapsulated the idea supported by those who wanted government at the most local level. In a pamphlet circulated in 1776 entitled The People, The Best Governors (anonymously) called for a single, popularly elected state legislatures and judges, universal male suffrage, and the idea that state governments existed primarily to coordinate the actions and wants of local governments.

To check the “unthinking many” conservatives (those who were Whigs during the colonial period) called for checks and balances in government, but that the best government was a strong federal government to coordinate among the states. This philosophy called for a national, bicameral legislature with an upper house consisting of landed elite and a lower house of popularly elected representatives.

State Constitutions

Maryland embraced the Whig, or conservative, approach. The delegates who wrote their state’s constitution came from those who held power during the colonial period, mainly large landowners. There was a property qualification to vote that was so restrictive that only about 10% of the male population would have qualified to vote. The governor would be all powerful and would be elected solely by the large land owners. One of the duties of their governor was to appoint lifelong judges.

One of the more radically democratic state government was that of Pennsylvania. Those who helped draft their state constitution had to have served in the state militia. They called for a unicameral legislature, suffrage extended to all free, make, taxpayers. There would be no governor, instead the state would be led by the legislature, which would hold their meetings freely and would be open to the public. And unlike in Maryland, judges would be voted in and thus could be voted out of office.

Enumerated Rights

George Mason, a wealthy Virginia landowner, believed that their state constitution did not go far enough to safeguard their liberties. Thus, he drafted a list of what he called inherent rights. His list contained 16 rights or liberties to include the idea that government power derived from the people (and thus the people could disband the government), and guarantees of due process, a trial by jury, and a prohibition on cruel or excessive punishment. He noted certain freedoms such as that of an independent press, the freedom to freely assemble, and that the state would not have an official religion. At least eight states incorporated some or all of Mason’s ideas into their own state constitutions. Later, Mason would insist that the Constitution contain a list of specific rights or liberties, which became the first ten amendments to the Constitution, also known as the Bill of Rights. The Virginia Constitutional Convention adopted Mason’s Declaration of Rights on June 12, 1776

The Articles of Confederation

The country’s first compact came about due to new socio-economic realities of the Revolutionary era. First, a pro-democracy movement grew. With the expulsion of tens of thousands of Loyalists, the traditional, conservative British leadership was replaced by more democratic American leadership. Laws such as entail and primogeniture weakened the established elites and slavery began dying a slow death, at least in the northern states such Vermont, for example, ending slavery in 1777 and other states adopting various measures that would result in the prohibition of slavery. The Church of England (the Anglicans) were replaced by the more American religious movement, the Episcopal Church and democracy in religion spread to the western frontier with new religious ideas such as Methodism and Baptism gaining followers. Beginning in Virginia, the idea of the separation of church and state spread throughout the new states.

There were also economic stresses. The American economy was intimately tied to England and so with trade coming to a standstill during the Revolution, the American economy faltered. Speculation and profiteering led to inflation and some aspects of the economic reasons behind the War resulted in somewhat of a rejection of taxes. The Second Continental Congress picked up the baton of coming up with a national agreement in 1777. However, that compact was not ratified by the states until 1781. At that time, there was neither an executive nor a judicial court and so Congress was the dominant force. Congress, as some have pointed out, was restricted or slowed down by their strict rules. For example, all bills needed a 2/3rds vote for passage. Any amendment to the Articles required a unanimous vote.

Each state had one (1) vote. Congress had no power to regulate commerce or engage in most coordination among the various states. For example, Congress could raise taxes but lacked the power to collect taxes. States had the power to pay or reject taxes coming out of Congress. So, to help pay off the debt, Congress sold much of the northwest territory. Land was divided into townships six miles square then further divided into 36 sections of one square mile each. One out of the 36 one square mile sections were reserved for construction of public schools. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated that there would be the creation of new states, with equal rights of the original 13 states. Territories needed at least 60,000 settlers before they could join the union. And, slavery was prohibited in the territories. Congress also had limited power in foreign matters. For example, England refused to send an ambassador, or any representatives, to make commercial treaties or to repeal the various Navigation Acts. Spain seized land along the Mississippi River, and France demanded that the fledgling country pay back its wartime loans and to not trade with their colonial holdings in the Caribbean.

Revolution and Religion[31]

The American Revolution was fought against the English monarchy and its government. Issues related to governance like taxation, representation, and self-governance were central to the revolution, religious affiliation were not. Prior to the war the Anglican church, the offshoot of the Church of England, was the second largest denomination in the American colonies but after the war the church suffered mass exodus. The Episcopal Church lost membership because of its association with England and the Monarchy, a diminished number of congregants, and a weakened rank of clergymen.

At the end of the war the church was “severely weakened in most of the newly-independent states and on the verge of extinction in others”[32] This came about for a variety of reasons over the course of a few decades. Prior to the war, Anglican parishes were established across the colonies and often given land grants that allowed clergy members to support themselves on the land attached to their parish. This allowed for increased clergy interest and their ability to practice without the support of others if necessary. During the war many clergy fought and had their livelihoods diminished as a result of the war. The newly formed state governments sought retribution against the Church because of its association to England and the monarchy and began confiscating land associated with parishes and thereby diminished the ability of clergy to support themselves. These attempts at defunding the Church were effective.[33]

Splintering of the governance of the Church in America also led to decrease in cohesion among the top levels of the Church. The argument for and against bishops in America took many years and diminished their ability to unify the parishes under a commonality of governance. Beyond their failure at rectifying such issues as allegiance to the Church of England and allegiance to the State governments, the Church dealt with systemic issues. Issues of “persecution, emigration, death, and the lack of new ordinations has a precipitous effect on the number of left in the 13 colonies at the end of the war.”[34] In short, parishes closed because there were not enough clergy to go around. Membership declined and other denominations began to take root and replace the abandoned parishes. Membership in the church declined by 40% during the war . Decline in membership can be attributed to a patriotic desire to distance oneself from the perceived English relationship of the Church by patriots and immigration of those loyal to the Crown out of the colonies for fear of persecution. With a diminished number of parishioners there came a reduced need for parishes.[35]

Being the second largest denomination in the colonies pre-war gave great influence to the Anglican Church. Had this continued then current religious trends would likely be different. Instead, as the influence of the now Episcopal church faded after the war, the influence of its associations (England and the monarchy) did as well. Furthermore, it created a vacuum that other denominations were then able to fill in the religious lives of the citizens of the fledgling America. These people took these ideas from Methodist, Baptists, and other denominational teachings and would vote/legislate with these principals in mind. These likely led to a further divergence between American culture and government tradition and that of England. While a secular state on paper, America has been greatly influenced by religion over more than two centuries with every President claiming association to some denomination of Christianity.

The Episcopal Church was a bystander casualty to the American revolutionary war. While not directly involved in the war, the church suffered greatly as a result of the war and saw a massive drop in prominence in the colonial, and then American culture. Association with the crown, a decreased membership, and a reduced clerkship all caused a reduction in the church in America and led to it having a diminished role in the formative and later years of the new nation.

The American War for Independence came to an official end with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, just two years after the Articles of Confederation were made public. War is easy, revolution is hard. The War was over, now came the hard part of creating these United States.

I’d like to thank Rebekah Hankins for her interest in sacrifice through the lens of culture. She was a student of mine in the Fall of 2019 and wrote a brief essay that appears at the beginning of this chapter as well as Fnu Zabihullah, also a student of mine in the Fall of 2019, who had an interest in military history. And finally, Manuel Morin, a Marine, who researched and wrote that excellent piece on the early history of the US Marines. I thank you all.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies. Please point them out to me so that I may make make this chapter better. I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Leaving the references to air power aside, the McHenry tag is about the War of 1812 not the Revolution. ↵

- 8.2James Ambuske et al., “The American Revolution,” Michael Hattem, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). Available http://www.americanyawp.com/text/05-the-american-revolution/ (last accessed October 13, 2019). 3 ↵

- Emily Arendt et al., “Colonial Society,” Nora Slonimsky, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). Available http://www.americanyawp.com/text/04-colonial-society/#IV_Pursuing_Political_Religious_and_Individual_Freedom (last accessed October 13, 2019). ↵

- James Ambuske et al., “The American Revolution,” Michael Hattem, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). Available http://www.americanyawp.com/text/05-the-american-revolution/ (last accessed October 13, 2019). ↵

- https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1777/battle-of-princeton/ ↵

- He was a student of mine in the Fall of 2019. ↵

- Tindall,George Brown, and David Emory Shi, America: a Narrative History , Vol 1, 10 th ed, New York: W.W. Norton & Co,2016,163 ↵

- ushistory.org, the American Revolution, U.S History online textbook , http://www.ushistory.org/us/11.asp, Saturday, October 12, 2019 ↵

- Fnu Zabihullah Fall 2019 ↵

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/deborah-sampson ↵

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/margaret-cochran-corbin ↵

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/nancy-morgan-hart ↵

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-ludwig-hays ↵

- https://www.amrevmuseum.org/read-the-revolution/history/belonging-army ↵

- https://www.historynet.com/dragging-canoes-war.htm ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonel_Tye#cite_ref-:1_2-6. No page number listed in the original source: Sutherland, Jonathan. (12 January 2003). African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia ↵

- https://historycollection.co/african-american-loyalists-during-the-revolutionary-war-10-significant-people-events-and-things/10/ ↵

- https://hccsaweb.hccs.edu:8080/psp/csprd/?cmd=login&languageCd=ENG& ↵

- This section was researched and written by a retired Marine, Manuel Morin (Spring 2020) ↵

- No author, Brief History of the United States Marine Corps, https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Brief-Histories/Brief-History-of-the-United-States-Marine-Corps/ Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- No author, Parliamentary taxation of colonies, international trade, and the American Revolution, 1763–1775, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/parliamentary-taxation Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- No author, Battles of Lexington and Concord, https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/battles-of-lexington-and-concord Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- Wallace, Willard M., American Revolution: The War at Sea https://www.britannica.com/event/American-Revolution/French-intervention-and-the-decisive-action-at-Virginia-Capes Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- Smith, Charles R., Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, https://www.genealogycenter.info/military/revolution/search_marinesrevwar.php pages 9 & 10 ↵

- Smith, Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, https://www.genealogycenter.info/military/revolution/search_marinesrevwar.php page 10 ↵

- Ibid., pp 12-13 ↵

- No author, Sons of the American Revolution, History of the Continental Marines, https://www.southcoastsar.org/continental-marines/ Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- Smith, Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, https://www.genealogycenter.info/military/revolution/search_marinesrevwar.php pages 17 &18 ↵

- Davis, Robert Walker. "Marines in Review, 1775-1950: A Report on the USMC Exhibition, Truxtun-Decatur Naval Museum." 62-64 Last accessed 03 13 2020 ↵

- Smith, Marines in the Revolution: A History of the Continental Marines in the American Revolution, https://www.genealogycenter.info/military/revolution/search_marinesrevwar.php pages 11 & 12 ↵

- This section was the result of the work of Kamila Gutierrez Ruiz in the Spring of 2020. ↵

- Holmes, David L. “The Episcopal Church and the American Revolution.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, vol. 47, no. 3, 1978, pp. 261–291. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42973625. Accessed 13 Mar. 2020. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Prichard, Robert W. A History of the Episcopal Church. Church Publishing, Inc., 2014. ↵

- Holmes, David L. “The Episcopal Church and the American Revolution.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, vol. 47, no. 3, 1978, pp. 261–291. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42973625. Accessed 13 Mar. 2020. ↵