27 Interwar America

Harlem Renaissance, Mass Murderers, and Mexican Repatriation

Annie Louise Burton. Always intent on bettering herself, in 1900 Annie Louise Burton started attending a night school in Boston. She took classes at this school for about six years, and at the same time, she began work on the two autobiographical essays in her book Memories of Childhood’s slavery.[1] In her simply written narrative, she offers extraordinary resistance to the emerging racial caste system of Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction America.2 The story of her voyage from slavery in Clayton, Alabama, to domestic work in the industrial North, and finally to business-ownership in Jacksonville, Florida, charts the powerful economic and social forces that attempted to re-inscribe a system of slavery onto the first generation of nominally freed African Americans. Although her childhood was tough and she was a part of slavery, her bravery to continue forward and fight to better herself with all the obstacles that got in her way, she was able to share her story publicly for many and that makes Burton someone important in History. Burton’s Memories of Childhood’s Slavery Days details not only one woman’s quest from slavery to physical freedom but also her journey from a proscribed role to the creation of her own free identity.[2]

The interwar period was an active period in US history to include political scandals (Teapot Dome and Warren G. Harding’s illegitimate child), attempts to prevent future war (Kellogg-Briand, the Washington Conference treaties, London Naval Conference), Fundamentalism vs. Modernism (Father Coughlin, the Scopes “Monkey” trial and birth control, the rebirth of the Klan, prosperity and consumerism, and the “Roaring Twenties.” Singing, dancing, and boozing it up are overemphasized elements of this period. And, certainly this period was not “roaring” for people of color.

The Scopes Trial is an important part of history because it symbolizes the conflict between science and theology, faith and reason, individual liberty and majority rule.[3] During the 1920’s many southern states passed laws making illegal to teach Darwin’s Theory of Evolution in schools including Tennessee. Instead it was encouraged to teach a version of the creation story found in the biblical book of Genesis. Darwin’s theory went against the views of the people’s religion which was Christianity.[4] Darwin’s Theory of Evolution essentially says that individuals of a species are not identical, traits are passed from generation to generation, more offspring are born than can survive, and only the survivors of the competition for resources will reproduce.[5]

The man that stood in trial for violating the law was John Scopes, a teacher. He did not stand a chance because the trial judge did not allow the defense to use scientists as witnesses. Scopes was defended by Clarence Darrow and prosecuted by William Jennings Bryan. Clarence Darrow was a democrat and was skeptical towards religion.[6] Darrow saw it unnecessary to band schools from teaching evolution which caused him interest in the trial. Before he took up this case, he was successful in two other cases that caused controversy. In one he successfully defended William Haywood from a charge of plotting to murder the former governor of Idaho. In the other he saved two Chicago college students from the death penalty for murdering a youngster. Darrow was known for his involvement in risky cases, so the Scopes trial was in his spectrum.[7]

The prosecutor, Bryan, was also a devoted democratic but unlike Darrow he was a strong believer in religion. He argued that the teaching of evolution would undermine traditional values he had supported and because he has a compelling desire to remain in the public spotlight – a spotlight he had kept since his famous “Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 Democratic convention.[8] When Bryan was brought up as a witness by Darrow during the Scopes trial it revealed his shallowness and ignorance towards science and archeology.[9]

This case puts a light on faith and reason. Two men who were both democratic did not agree whether evolution should be taught or not because one had religious views and the other did not. Faith is believing something without having evidence while reason is coming to a conclusion by having facts and data. Bryan did not want evolution to be taught at schools because it went against what he believed even though there was reason behind teaching evolution in schools. Not everything is going to please everyone’s views but that is why we have reason to know what the right thing is. This also agrees with science and theology. Theology refers to the belief in god just like faith and science is determined by reasoning and a vast amount of research.[10]

Individual liberty and majority rule is the conflict between practicing what you desire versus what the majority want is what should be. In the Scopes trial majority did not want Darwin’s theory being taught in schools because it went against their Christian views, but few argued that everyone has an individual opinion. This meant that even though evolution went against people’s religious beliefs it should not be held from others because everyone can form their own opinion.

The Scopes trial gained a big following [as many Americans followed the] broadcast on the radio. The trial was marked by hoopla and a carnival-like atmosphere. Thousands of people swelled the town of a thousand. For 12 days in July 1925, 100 reporters sent dispatches.[11] Darrow changed Scopes plea to guilty which led Scopes to be found guilty and must pay a fine of $100. However, the conviction was thrown out on a technicality by the Tennessee Supreme Court: that the judge, and not the jury, had determined the $100 fine. Scopes left his teaching days and became a chemical engineer. In conclusion, the Scopes trial paved the way for science being taught in schools. It also shined light on many basic human rights that were being abused.[12]

“Variously known as the New Negro movement, the New Negro Renaissance, and the Negro Renaissance, the movement emerged towards the end of World War I. blossomed in the 1920s, then faded in the 1930s. The Harlem Renaissance marked the first time that main stream publishers and critics took African American literature seriously and that African American literature and arts attracted significant attention from the nation at large. Although it was primarily a literary movement, it was closely related to developments in African American music, theater, art, and politics.”[13] The Harlem Renaissance is a nutshell was about the ability to self identify to the world, much like Burton did in her works.

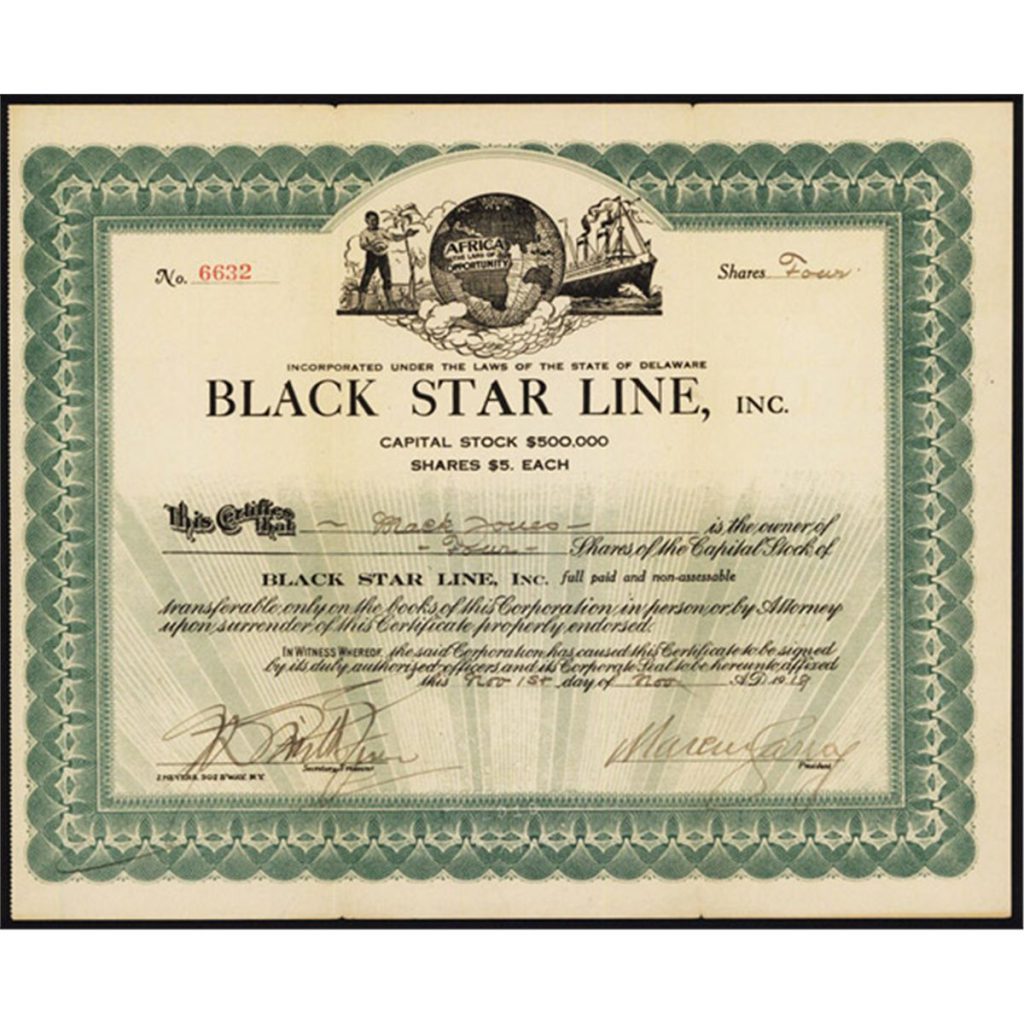

An element of the Harlem Renaissance was independence. A pre-Harlem Renaissance supporter and leader was Marcus Garvey. Garvey was from Jamaica. He called for a universal understanding of their shared heritage and co-existence of people of African descent with people living in Africa. He envisioned a pan-African society (with himself as the community’s leader) in Liberia.

To that end Garvey created black-only organizations and institutions such as the Black Cross nurses and the Black Star line. He helped establish the African Orthodox church, which included Black Christ and the Back Madonna. He argued that God manifested himself differently to each race or ethnicity. These and other organizations fell under his umbrellic Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

In 1916 Garvey came to the United States where he lectures to African American audiences and raised money for his various ventures. For example, Garvey had published a newspaper, the official organ off the UNIA called Negro World. Through that publication, Garvey was able to reach more people with his message that African Americans should start their own businesses in order to become economically stable in preparation for the massive move of African Americans to Africa.

African Americans created those businesses, manufactured a variety of goods and Garvey had those products shipped to Africa. But he made most of his money from importing, quite illegally, alcohol. This was the time of Prohibition and the transportation and sale of alcohol was illegal under the Eighteenth Amendment. One of his ships was seized, the cargo discovered, and Garvey was imprisoned in 1925. After serving slightly more than half of his five-year sentence, the US government deported Garvey to Jamaica.

His calls for all people of African descent to be aware and proud of their African roots and heritage, to become educated and economically independent, are all themes supported by the thinkers, writers, and painters of the Harlem Renaissance.

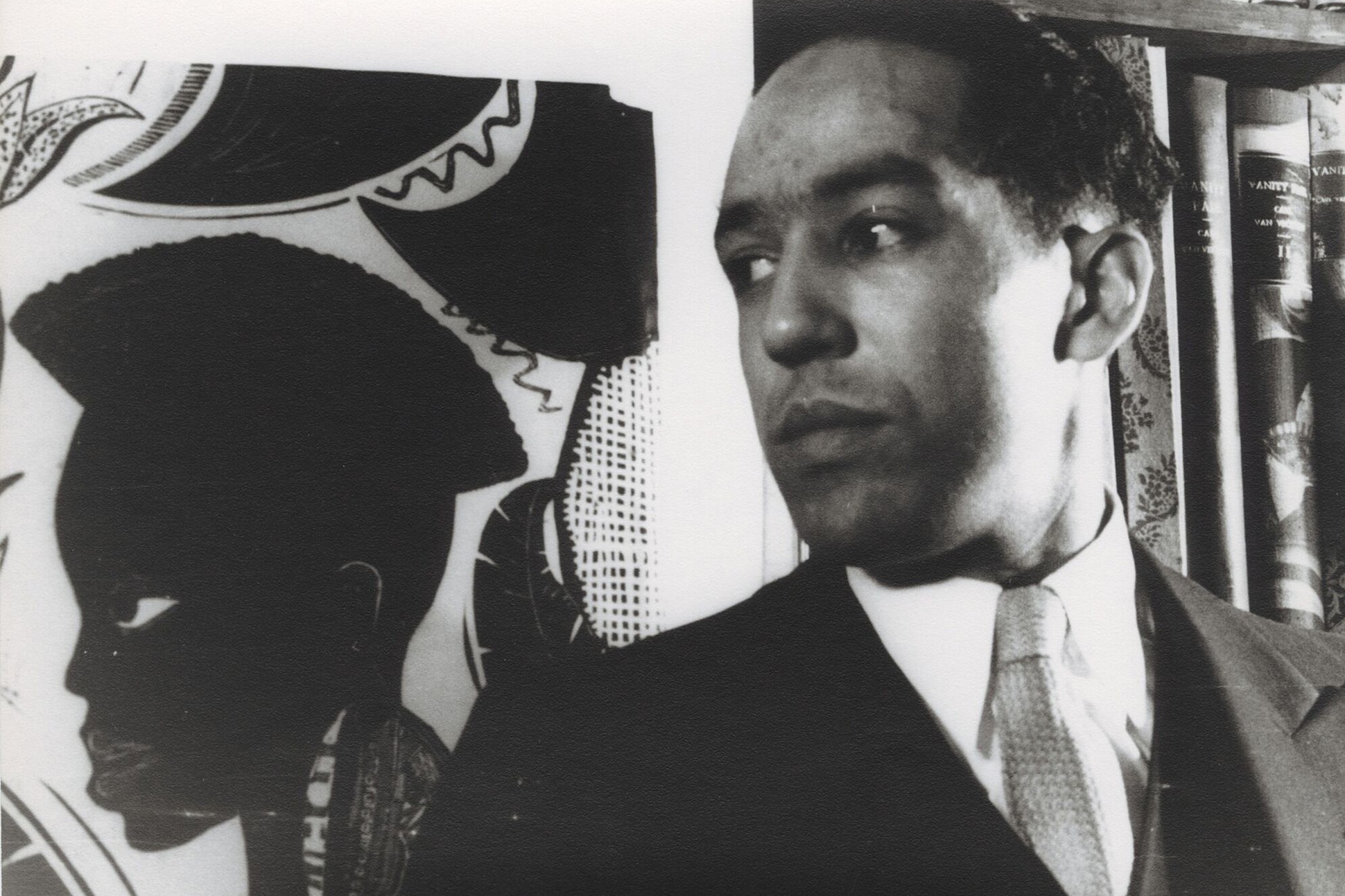

Possible the intellectual linchpin of the Harlem Renaissance was Alain Locke. In 1925, Locke edited an anthology of arts and humanities on African and African American culture entitled The New Negro: An Interpretation. Locke obtained his undergraduate degree and PhD from Harvard. He was a Rhodes Scholar and the chair of the Philosophy Department at Howard University.

Jeffery Stewart, who came out with a biography on Locke in 2018 had this to say about Locke: “Locke became a ‘mid-wife to a generation of young writers,’ as he labeled himself, a catalyst for a revolution in thinking called the New Negro. The deeper truth was that he, Alain Locke, was also the New Negro, for he embodied all of its contradictions as well as its promise. Rather than lamenting his situation, his marginality, his quiet suffering, he would take what his society and his culture had given him and make something revolutionary out of it.”[15]

Langston Hughes is one of the most renowned writers of all time. Hughes was a young man when the Harlem renaissance began. But gained notary when getting poems published in The Crisis.[16] Hughes got wildly criticized by African Americans intellectuals for the way he depicted the negro life. Hughes did not relate to the other black scholars as much as he could relate to the common black man, so he wrote about the struggles and what he felt. Hughes before the age of 12 had lived in six different cities.[17] Hughes worked as a truck farmer, cook ,waiter, sailor, and doorman.[18] Hughes traveled the world and was able to see what a world was like without so much racism, as he spent a great deal of time in Europe studying and working. Through his life experience and knowing there was a better way for African Americans he expressed this in his writings. Hughes Second published book was a big hit with major publishers but was harshly criticized by African american critics.[19] The headline for the New York Amsterdam was LANGSTON HUGHES THE SEWER DWELLER another paper read LANGSTON HUGHES BOOK OF POEMS TRASH. Although Hughes was ostracized by a lot of black publishers, The Crisis published and thought highly of Hugh’s writings.[20][21]

Writers who seldom appears in textbooks include Jessie Redmon Fauset. James Weldon Johnson and Richard Bruce Nugent. Jessica Figueroa took a look at Fauset. Jessie Redmon Fauset is an African American novelist, critic, poet, and editor is known for her discovery and encouragement of several writers of the Harlem Renaissances.[22] She is remembered as one of the literary midwives of the Harlem Renaissance, an influential circle that ushered in a new generation of creative voices in the black arts movement.[23] From 1919 to 1926 Fauset was a literary editor of The Crisis, she moved to New York City to work with W.E.B. DuBois on the magazine and his work on Pan African Movement.[24] She contributed since 1912 reviews, translations, short stories, essays and biographical sketches to the magazine. She served as a literary editor of The Brownies Book, according to W.E.D Du Bois it was directed to African children stating that their color is normal and beautiful an make them familiar with their history and achievements of African race. Fauset’s 1925 essay, The Gift of Laughter, is a classical literacy piece, it analyzes how American drama used African characters in roles as comics. This essay discloses the limitations on African actors caused by stereotype, and how these actors couldn’t seem to arrive at their actual potential as serious actors.[25]

During the Harlem Renaissance Fauset published four novels: There is Confusion, Plum Bun, The Chinaberry Tree, and Comedy: American Style. Her difficulty in finding suitable outlets for her work was the result of publishers de- emphasizing the lives of middle-class Africans than of the literary quality of her writing. These novels are based on African professionals and their families, facing American racism and living their rather non-stereotypical lives.[26] Fauset published her first novel There Is Confusion in 1924 shows awareness of the African middle class quest for social equality in the early twentieth century and of the limited vocational choices confronting both African and white women in that era. Her second novel Plum Bun was published in 1929 is a about a young African girl that discovers she can pass for white and moves to New York believing her only obstacle to opportunity is racism. She soon discovers that being a women has its own burdens and doesn’t fade with color of one’s skin, and that love and marriage might not offer salvation. Her third novel The Chinaberry Tree was issued in 1929, it offers a modern perspective on the struggle of African American heroines toward self- knowledge, it is a depiction of interracial love and marriage. In 1933, her fourth novel Comedy: American Style was published, it explores the tragic effect of color prejudice and self-hatred. It portrays internalized racism with its depiction of a domineering mother whose determination for her children to pass as white leads to devastating results for the entire family.[27] Fauset’s four novels reach her aim towards politicized issues of color, class and gender. It revises standard literary forms and themes she reveals her critically political nature of her novels. Jessie Redmon Fauset wrote about middle-class African life, racial discrimination, and those who passed to avoid discrimination. Fauset published four novels that novels were based on African professionals and their families, facing American racism and living their rather non-stereotypical lives.[28]

Another example at a seemingly unknown figure of the Harlem Renaissance was James Weldon Johnson. Luis Gonzalez and Jeason Pardo examined Johnson’s contribution to the Harlem Renaissance. James W. Johnson played a major role during the interwar period who was a leading figure in the creation and also the development of the Harlem Renaissance. He was a writer, politician, and a lawyer among many other things. He wrote many poems and books like the God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, Negro Americans, What Now? Black Manhattan, etc. He also was a civil rights activist and participated in many cases.

James W. Johnson got his education in the University of Atlanta and the Columbia University. Early on in his time there he started to practice law and did not find success early on and he decided to quit law. But he did find success later in writing poems and books. In 1920, he published The Book of American Negro Poetry which was successful in influencing the Harlem Renaissance movement. Also, he became the NAACP first black general secretary in 1920. During his time working there he helped define this organization as an organization that focuses on civil rights. For example, the NAACP was involved in many prominent Jim Crow battles of the time, including the Dyer-Anti Lynching Bill.[29] He also published The Book of Negro Spirituals in 1925. He proved to be a person that lead and influenced the Harlem Renaissance at the time. For example, James W. Johnson in 1921 pushed for a Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which was passed in the House of Representatives but ended up being blocked by the Senate since they were mostly Democrats.[30] He also encouraged young African American authors to publish their creations and he also supported them in order for them to be able to publish their works. During the 1920s-1930s, a large group of African American poets grew into what was considered to be the “New Negro poets.” Their poems were made into various of ways of expressing what they felt life was like into an artistic manner.[31]

In 1930 he also published his book called Black Manhattan and in that same year he stepped down from his position at the NAACP. This book talked about black history and covers different neighborhoods where African American’s lived and how they expanded to Harlem as their thoughts and customs changed. It mostly focused on where it all started from when the first African Americans came to the United States. In 1934 James W. Johnson became the first African American professor to be hired by the New York University. In the same year he went and published an argument called Negro American, What Now? that targeted racial integration.[32] This argument also talked about how the African American Community has many choices to choose from in order for them to move forward but that there is no clear solution to the problems that they face now. James W. Johnson wrote this book for the black community to see that the only choice that they have is to become self-sufficient and to not rely on other people. With the influence he established and his death in 1938, two thousand people attended his funeral.[33]

The interwar period was a big step for the African American population in the United States with the introduction of the Harlem Renaissance. James W. Johnson’s part in creating and leading the Harlem Renaissance and influencing different people to band together caused an uproar in African Americans being able to express their poems and musical talent to the majority of the Western Culture through, what they considered, “noise”.[34][35]

Richard Bruce Nugent was an African American author and painter, who was openly gay and became a great influencer in the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance, known at the time as the “New Negro Movement”, was an intellectual, social, and artistic explosion taken place in Harlem, Manhattan, New York. Nugent’s career was very productive by bringing to light the creative process of gay and black culture.

African Americans experienced an abundance of institutionalized racism in the South therefore, most of them relocated to the northeast and Midwest. They sought a better lifestyle away from the south leading to the Great Migration. Harlem soon became an African American neighborhood in the early 1900s. Hubert Harrison, “the father of Harlem Radicalism” founded the first organization and newspaper, respectively, of the “New Negro Movement” titled The Voice. The newspaper published poetry and nevertheless, came a sense of acceptance for African American writers. Bruce Nugent was one of the artists among the least known. Nugents’ first works as a writer were published in 1925 which included one of his poems titled “Shadow” where he compared himself to a shadow.[36] During his career in Harlem, Nugent published his short story “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” in his roommates, Wallace Thurman, publication “Fire!!‘ with many more artists. This piece emphasized the subject of bisexuality and interracial male desire.[37]

Furthermore, Bruce Nugent’s illustrations were also featured in the publication “Fire!!”. The Harmon Foundation’s exhibition of African American artists was one of the few venues available for black artists, it included four of Nugent’s paintings. He was able to work with many iconic Harlem Renaissance writers on the Federal Writer Project, which was a federal government project created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers during the Great Depression. Nugent’s lifestyle was that of the ultimate bohemian, he did as he wanted and did not care for others’ expectations or norms regarding himself.[38] Richard Bruce Nugent had a publication consisting of his own work, Beyond Where the Stars Stood Still, was issued in a limited edition by his future brother in law, Warren Marr II. Nugent went to marry Marr’s sister, Grace that lasted 17 years until she passed away. Admitting that the love he had for her was not physical love or lust.[39]

Much of the Harlem Renaissance was a wide spread appreciation/interest in black culture to include music and art. Some of the biggest names of 20th century American music were products of the Harlem Renaissance to include:

Louis Armstrong— although born in New Orleans and later moving to Chicago to perform with King Joe Oliver, his real chance came when he went to New York to get involved in the recording industry. With his group the hot six he took the use of a solo instrument (trumpet to new heights).

Cab Calloway— band director and vocalist and later a headliner at the Cotton Club Calloway is given credit for giving Ella Fitzgerald her start. He has starred in many movies throughout his career including the original “Cotton Club”. His most well known composition is titled “Minnie the Moocher”.

Duke Ellington— without a doubt the single most important musician of this era. He was the headliner at the Cotton Club from December 4, 1927 into the 1930’s. Born in Washington D.C., Duke started performing music at an early age although he was awarded a fine arts scholarship.

Ellington played the piano but, his real instrument was his orchestra. Since his death the tradition of the Duke Ellington band has been carried on by his son Mercer.

Dizzy Gillespie— probably the most well known and recognized bop performer. Dizzy has appeared in motion pictures, television, radio, and record albums. His solo instrument is the trumpet which has some distinctly different characteristics. His trumpet has an elongated bell and when he performs on it his cheeks usually puff out.

James Flecther Henderson— a headliner at the Savoy Ballroom in the 1920’s and 1930’s. A well educated college graduate who originally came to New York to attend Columbia University. Early in his career he worked for W.C. Handy and finally Black Swan Records with Louis Armstrong. With his famous band which included Chick Webb, he helped to strip New Orleans and Chicago as the hub of jazz. His music was pure and simple, jazz at it’s finest.[40]

African Americans created their own clubs and performance halls. Some of the more famous night clubs included:

The Cotton Club— located at 644 Lenox Avenue flourished from 1921-1936. Originally it was owned by well known gangsters, this club was famous for Broadway like floor shows. Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway found a “home” here for many years as headliners. The club featured all black performers although no blacks were permitted as guest. The Cotton Club was closed in 1925 by federal agents for violating prohibition, but soon reopened. It was closed again on February 15, 1936 and moved to 47th Street between Broadway and 7th Avenue. Before being named the Cotton Club it was known as the Douglas Theatre owned by then Heavyweight Champ Jack Johnson.

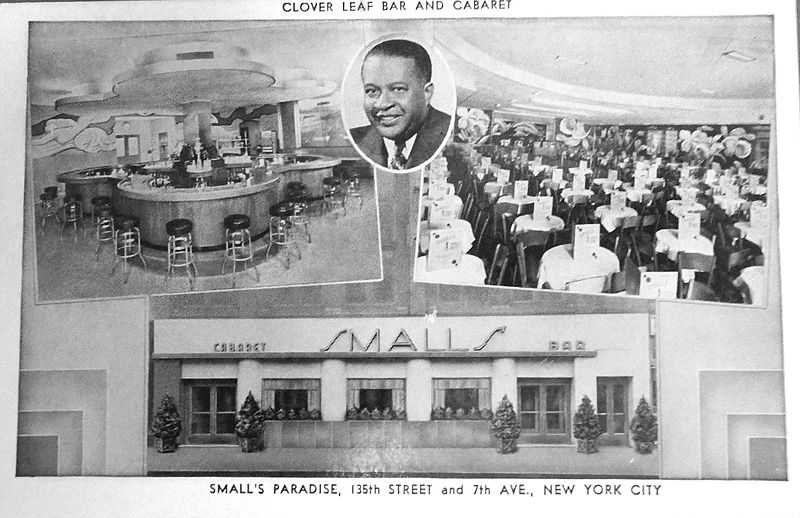

Ed Smalls Paradise- located at 229 1/2 7th Avenue, opened on October 26, 1926 and closed in the mid 1960’s making it the longest operating night spot in Harlem. In its hayday it featured singing and dancing waiters. Throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s it featured an array of talented jazzmen. In the 1950’s Rock ‘n’ Roll took center stage. In the 1960’s basketball star Wilt Chamberlain purchased the club and featured Ray Charles as his top performer. Finally in the 1970’s with the coming of disco, Charles Higgins (husband of singer Melba Moore) purchased the club and tried to make it happen once again, he failed and it was sold to Carl Gearwood, a West Indian who tried to make it into a community oriented club with a theatre.

Connies Inn— located at 165 131st Street, featured Fats Waller as it’s top performer after he was originally hired as a delivery boy in the 1920’s. During the Harlem Renaissance celebrities of stage, national figures, and members of high society all partied from dusk to dawn at Connies.

Savoy Ballroom— opened on March 12, 1926 as the largest ballroom in Harlem. It occupied the entire second floor part of the building which took up a full block from 140th to 141st Street on Lenox Avenue. It was once called “The world’s most beautiful ballroom”. Harlemites who frequented the club were known as “the track”. The major feature of the Savoy was “the battle of the bands” which began in the 1920’s by Harlem businessman Charles Buchanan and owner Moe Gale. This was a tremendous crowd getter sometimes attracting 5,000 people.

The featured performers, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb would be pitted against bands from New York, Chicago, and New Orleans. Many times these battles would cause riots in the streets. The most famous battle occurred in 1936 featuring Chick Webb against Benny Goodman attracting over 20,000 people. The swing era and songs like “stomping at the savoy” helped spread the clubs fame and kept it open. The savoy was finally torn down in 1958 for a housing project.[41]

Music had a dramatic chance during the Harlem renaissance, the biggest change to music was to jazz as it started to evolve. The piano for the first time was being used in jazz this was very significant as it was typically seen as only a classical instrument. This new change fundamentally affected the instrument and its perception as the piano was typically seen as a rich man’s instrument, while the typical brass instruments like the sax, trumpet and trombone where seen as the typical instruments for jazz.[42] The usage of the piano in music, more specifically jazz, which was the “negro music” became the bridge between the different classes and cultures of Americans. The rise of artist such as James P. Jonson, Fats Waller, and Willie Smith became inevitable with the new style of stride piano in jazz.

This music being the popular new wave, even the high class became interested in checking it out and eventually jazz started to get the sophisticated view. Even whites started to enjoy this music and the term “black and tan” clubs started to emerge.[43] This being clubs of different types that included jazz where both black and whites could attend. In a time where segregation was in full effect with Jim Crow laws and massive violence in the south this was crazy.[44] With the massive buzz that Harlem was making not even whites could stay away.

Unfortunately, this was not the case for African American elites. The African American high class saw the music as ghetto and silly folklore. This being the time where culture was being changed and there was a new type of black citizen, the new negro, the typical aspects of jazz weren’t really seen as new, it was more of the old. A culture that is finding themselves around a renaissance of so much art, film and writing didn’t want to go back but rather forward. It’s no surprised that the African American elite didn’t accept and saw this new jazz as sophisticated to be part of the new negro.

Although not accepted by the elite African Americans, the new jazz in Harlem was offering the common man a new way to express their culture and thoughts. Slavery had been terminated for a couple of years but there was a lot of segregation. Music was one of the few ways where an African American could really be free. This new type of jazz referred sometimes as Dixieland jazz, allowed such expression to really come through. Everything about the music was about feeling. There was no sheet music just a bases to start a song and to see where it would go. This was a true for of expression where African Americans could mix their African culture with their American. Song started to retell African folklore through music and artist added their own thoughts and emotions to it.[45]

The music was so powerful that even though it started as black music, whites quickly began to be inspired by it and started to be parts of this new type of music. For a small period, there was no segregation in the music. Both black and whites just wanted to express themselves and it led to the moment where this was even seen on The Congress Hotel in 1936. Teddy Wilson and Benny Goodman where seen performing.[46] A very significant moment in history where the color of the people didn’t matter. Although there had been previous works by both black and whites together this was the first time where a live performance and a mixing of the races occurred.The Harlem Renaissance was an amazing revival of African culture and its implementation into American culture. African Americans found their place in American culture through the arts. Jazz music being of the most significant to come out of the time. It united the races and classes even if for only a small time. Something that no other form of art did to this extent.[47]

The Lindy Hop was all the rage in 1930’s Harlem clubs. This article, written by Carl Van Vechten, was seen in the Brooklyn Citizen some time in 1930:

“Every decade or so some Negro creates or discovers or stumbles upon a new dance step which so completely strikes the fancy of his race that it spreads like water poured on blotting paper. Such dances are usually performed at first inside and outside of lowly cabins, on levees, or, in the big cities, on street corners. Presently, quite automatically, they invade the more modest night clubs where they are observed with interest by visiting entertainers, who, sometimes with important modifications, carry them to a higher low world. This process may require a period of two years or longer for its development. At just about this point the director of a Broadway revue in rehearsal, a hoofer, or even a Negro who puts on “routines” in the big musical shows, deciding that the dance is ready for white consumption, introduces it, frequently with the announcement that he has invented it. Nearly all the dancing now to be seen in our musical shows is of Negro origin, but both critics and the public are so ignorant of this fact that they production of a new Negro revue is an excuse for the revival of the hoary old lament that it is a pity the Negro can’t create anything for himself, that he is obliged to imitate the white man’s revues. This, in brief, has been the history of the Cake-Walk, the Bunny Hug, the Turkey Trot, the Charleston, and the Black Bottom. It will probably be the history of the Lindy Hop.”

“The Lindy Hop made its first official appearance in Harlem at a Negro dance marathon staged at Manhattan Casino some time in 1928. Executed with brilliant virtuosity by a pair of competitors in this exhibition, it was considered at the time a little too difficult to stand much chance of achieving popular success. The dance grew rapidly in favour, however, until a year later it was possible to observe an entire ballroom filled with couples devoting themselves to its celebration.”

“The Lindy Hop consists in a certain dislocation of the rhythm of the fox-trot, followed by leaps and quivers, hops and jumps, eccentric flinging about of arms and legs, and contortions of the torso only fittingly to be described by the world epileptic.”

“After the fundamental steps of the dance have been published, the performers may consider themselves at liberty to improvise, embroidering the traditional measures with startling variations, as a coloratura singer of the early nineteen century would endow the score of a Bellini opera with roulades, runs and shakes.”

“To observe the Lindy Hop being performed at first induces gooseflesh, and second, intense excitement, akin to religious mania, for the dance is not of sexual derivation, not does it include its hierophants towards pleasures of the flesh. Rather it is the celebration of a right in which glorification of self plays the principal part, a kind of tersichorean megalomania. It is danced, to be sure, by couples, but the individuals who compose these couples barely touch each other during its performance, and each may dance alone, if he feels the urge. It is Dionysian, if you like, a dance to do honour to wine-drinking, but it is not erotic. Of all the dances yet originated by the American Negro, this the most nearly approaches the sensation of religious ecstasy. It could be danced, quite reasonably and without alteration of tempo, to many passages of the Sacre Printemps of Stravinsky, and the Lindy Hop would be as appropriate for the music, which depicts in tone the representation of certain pagan rites, as the music would be appropriate for the Lindy Hop.”[48]

Art was another aspect of the Harlem Renaissance. My favorite artist is Aaron Douglas. This painting was unveiled at the Texas Centennial in 1936. To me, this painting demonstrated the story from slavery to that City on the Hill. At the bottom is darkness and from that darkness comes hands clearly chained together. The three people represent technology, commerce and industry, and education. The star represents the guiding start, the North Star either the literal star or maybe Frederick Douglass’s publication. The light forces the eyes to the upper right corner where there exists the city African Americans will build, that new City on the Hill that John Winthrop, Sr. spoke about in “A Modell of Christian Charity.”

But then I found this on the website of the de Young Museum: The painting “conveys Aaron Douglas’s perception of a link between African/Egyptian and African American cultures. He depicts a historical progression from slavery to freedom, and a geographic progression from the agrarian slave or sharecropper labor of the South to the industrial labor of the North. The shackled arms of slaves, rising from wavelike curves, evoke the transatlantic passage of slave ships. The five-pointed stars symbolize Texas—the Lone Star State—but also recall the North Star that guided escaped slaves to freedom before the Civil War.”[49]

However, the old problem continued to plague African Americans, particularly men. A suspicion, a rumor, or a perceived innuendo was all it took for a white mob to lynch an African American man on allegations of sexual assault, or intent. One such example happened in Scottsboro, Alabama in 1931.

Jobs were far and few between during the Great Depression -more so for African American men. Riding the rails was not an unusual way for men (and sometimes women) to get around the country in search for those illusive jobs. These were sometimes referred to as “hobos” or people without job or a place to stay who wandered from place to place.

A fight broke out in a boxcar between black and white riders. The fight seems to have been started when one of the white hobos tried to throw one of the black hobos off of the train. One of the guys on the losing side of the fight reported to police that he was attacked by a gang of black riders. The sheriff began stopping trains and and nine black riders, ranging in age from 13 to 20, were arrested. Two white women were also found by the sheriff, who then proclaimed that they had been raped by the black riders. Ruby Bates and Victoria Price were the two white women who made the allegations. Victoria Price had worked as a prostitute.

All but the 13 year old Roy Wright were found guilty of rape and sentence to death. There were several trials. Besides the air of intense racism in the Jim Crow South, one of the nine accused, Clarence Norris, initially testified that the women were raped by the other eight. He did not participate.

The eight were found guilty primary because that was the nature of Jim Crow. The Supreme Court overturned the convictions and ordered new trials. There will still be several who are found guilty. Most of the nine will be pardoned or paroled over time.

The KKK was a very public, very active, and very dangerous organization at the same time as the Harlem Renaissance. According to Adam Izaguirre, a student of mine in the Spring of 2020:

“On a national level, the KKK was never more influential than in 1924, when a dramatic split in the Democratic Party over the Klan destroyed its hopes of retaking the presidency” Starting the so called “second coming of the KKK” during these years the Klansman were gaining a lot of power becoming a threat to colored citizens of the U.S.[50]

But during this year it escalated more, violence began to escalate to dangerous levels to the police, having doing raids on local speakeasies and casinos, also destroying the home of Police Chief Lincoln Round, about three weeks later the Klan marched through Chicago’s downtown and were greeted with bricks and stone being thrown at them and gunshots, through these conflicts it reached the attention of Mayor Kistler on November 1st, 1924 having a peaceful resolution to the violence by letting them march but soon was left by a dirty surprise “a bomb blew up in Kistler’s house about two o’clock the following morning. The explosion made Kistler even more determined to allow and protect the parade” by doing so he chose 150 Klan members to protect the parade. The parade went well but it soon found itself having bloods in its hands, local Italian and Irish men, set up a blockade to stop the parade from the Niles to the field where they would meet for the parade, they also stopped local civilians to inspect their belongings, seizing Klan robes and weapons beating those who had them. After the parade started, bullets started flying, the local Klan guards and the police found it hard to stop the shooting. Though the shooting was long it ended with no casualties, there were never another KKK parade in the Niles, due to the harsh nature of the civilians and the local mobs.[51]

SERIAL KILLERS

Although Herman Mudgett is sometimes seen as this country’s first serial killer, the 1920s saw three of them in this essay by Sarea Crouch and Anayeli Ledesma, enttled “The Killer Twenties.”

The Roaring Twenties saw the emergence of serial killers as evidenced by the disturbing crimes of Carl Panzram, Peter Kudzwinowski, and Earle Nelson. As people became more liberated they also became more daring, and so some began to kill. The Roaring Twenties period known for music and culture also gave birth to the terrifying serial killer mania, that still occurs in modern America.

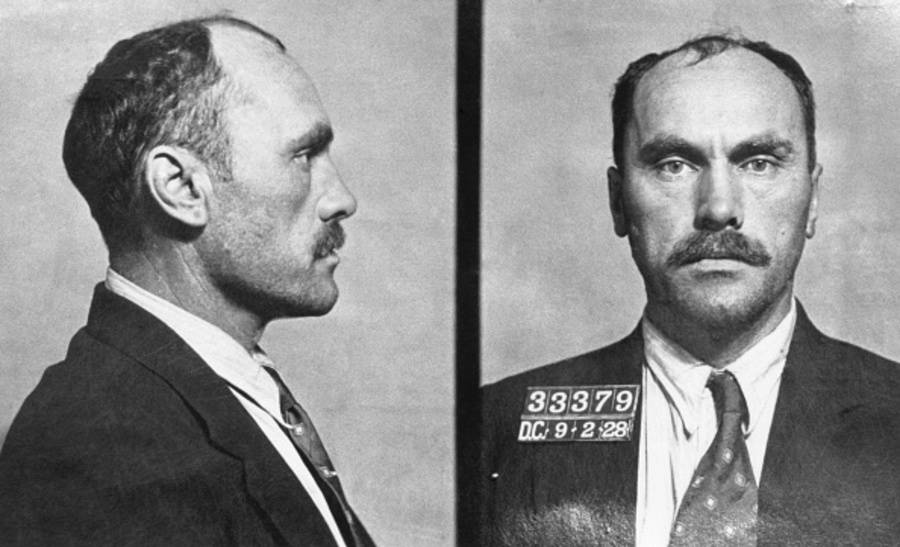

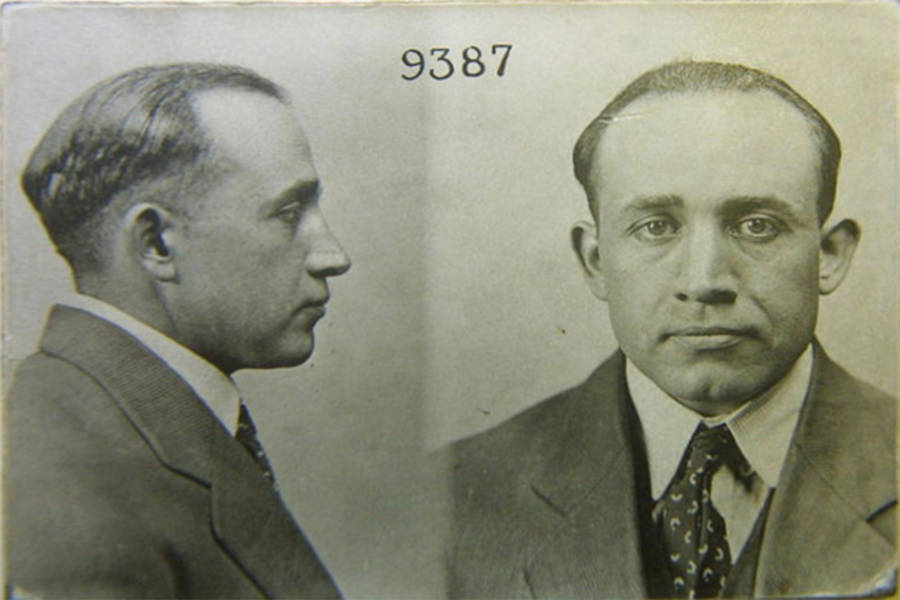

Carl Panzram (1891-1930) was no stranger to the law having committed several acts of burglary and frequently becoming incarcerated, however, it wasn’t until 1920 that he went on a killing spree. Carl was convicted of killing 21 people and raping young boys by 1928. Carl was eventually arrested and executed soon after killing the laundry supervisor and landing himself on death row. Carl remained brutally honest about his nature showing no remorse by saying “In my lifetime I have murdered 21 human beings, I have committed thousands of burglaries, robberies, larcenies arson’s and last but not least, I have committed sodomy on more than 1,000 male human beings. For all these things I am not in the least bit sorry.”[52] Most of Panzram’s murders were committed in the Midwest. It is also reported that he also urged his executioner to kill him by saying “Hurry it up you Hoosier bastard!”

Unfortunately, there was an even more vicious serial killer than Panzram and his name was Earle Nelson (1897-1928). Nelson was convicted for the murders of 22 people, including an infant and minor. What made his crimes particularly heinous in nature was his modus operandi. Nelson would strangle his victims, which were often elderly women, and engage in necrophilia with the corpses. This man’s crimes went on from 1926 until 1927; eventually he was tried and sentenced to death by hanging. Nelson’s crimes happened in the East Coast and the Midwest. It was reported that Nelson’s last words were “I forgive those who have wronged me.”[53]

Yet another serial killer from this age, although less notorious this time, was Peter Kudzinowski (1903-1929). Peter was tried for the murders of five people including a seven-year old boy and five-year old girl. Interestingly enough, he did not originally get arrested for murder, but instead went up to a police station himself and confessed to his crimes.[54] It was reported that he was under the influence of alcohol during two of the murders; most of the incidents are reported to have occurred in New Jersey, with only one taking place in Pennsylvania. Kudzinowski was tried and sentenced to death by the electric chair. Authorities claim that Kudzinowski wanted to be executed, as he was afraid he would continue his killing spree if left alive.

One thing that is oddly similar about these three men is their backgrounds; it seems that all of them had a particularly rough childhood, including accidents that affected their behavior afterwards. Peter Kudzinowski began to behave strangely after he hit his head in a shallow pool during the sixth grade. He began to act maniacally and unusually aggressive after this.[55] Similarly, Earle Nelson collided with a car while riding his bicycle, this resulted in him acting frantically and almost fanatically after the events. Some family members even report him talking about a beast in the Bible, while also watching his cousin Rachel undress. Nelson has often been called a “psychotic prodigy.”[56] For Carl Panzram, the situation was a bit darker. As a child he began to lie and steal, as a result he was sent to a military school. Panzram was beaten, tortured and raped in the institution, at the mere age of 11.[57]

In brief, although it is true that the Roaring Twenties were filled with immense cultural and social development and wealth, there was also a dark side to this progress. The rise of urban cities made it easier for crime to occur, and sometimes go undetected. These three men are only a few examples of the criminals found in America during the 1920’s.[58]

Before FDR began to save Democracy, there were other ideas tried to lessen the burden of the Great Depression on Americans, such as what was called the Mexican repatriation. Leonel Lizalde, Alejandra Lopez, Tatyana Marquez, Damian Mendez, and Paulina Mosqueda examined the mass deportation of Mexican and Mexican-American people.

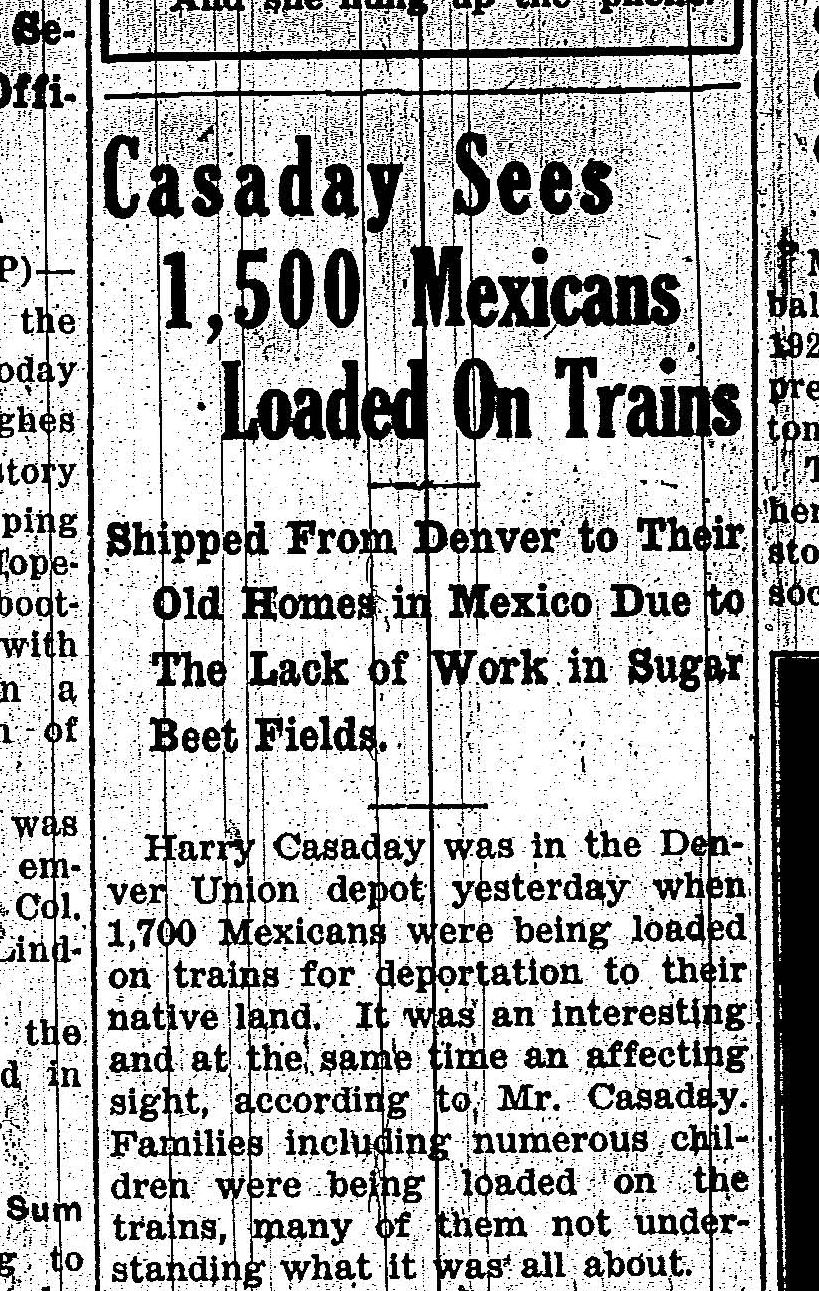

During the Great Depression, many Americans (especially immigrants and descendants of) were hit hard by the economic devastation, causing a divide in ideas and cultures due to the unexpected change and panic. The economic crisis in the 1930’s was a turning point for American society, leaving many without jobs and homes. The events that ensued afterwards were most likely caused by panic and the need to find the blame for the economic depression. Therefore, leading to the series of deportations of Mexican immigrants, descendants of immigrants, and any citizens that looked like Hispanic immigrants. This series of mass deportations across the nation became known as the Mexican Repatriation, and hispanic people were blamed by many for the depressions.[59] Because they were the most recent group of immigrants, Mexican-Americans were used as scapegoats and were believed to have been job stealers as well as taking advantage of the American benefits that came with their new lives here in the United States.[60]

During the Great Depression, president Herbert Hoover, was judged for not being able to improve the economy since the stock market crash in 1929. However, the secretary of labor at the time, William Doak, was the person who was interested in the repatriation projects.[61] A concept of “willingness” to return to a person’s homeland. Doak used every possible means to encourage repatriation and one example of that was the one in Los Angeles, CA. On February 26, 1931, at the peak of the great depression, in Los Angeles, California at La Placita park, a raid took place where officers took people of brown skin and grouped them up and sent the city’s main railroad station and taken back to Mexico.[62] This action makes it clear to us how “American’ people felt about “aliens” at that time.

Many of the Mexican-American families sent home were US citizens and had been living in the US for as long as twenty years. They were very well Americans for they led the same lifestyle and practiced American culture as the rest of society. The government restricted working opportunities for Mexicans by prohibiting the employment of “aliens”, having anti-Mexican policies, and as said before, limiting the amount of work visas. This eventually drove out Mexican-Americans to their ancestral home, Mexico, searching for jobs and ways to survive. They were forced to go back to a country unfamiliar to them, away from the lifestyle they grew up to.

In the article by Valenciana, she touches the topic of these deportations and believes strongly that the inclusion of this event becomes a part of the history curriculum in schools since it has remained hidden from society for years. This article also holds various interviews with the families who were unconstitutionally deported. Many Mexican-Americans were used to urban life so arriving in an unfamiliar country became a challenge. “We had to walk approximately fifteen to twenty miles to school. I resented the way we were taken from the United States and taken to Mexico and we had to struggle to live in a place where we had nothing.(Balderrama & Valenciana, 2004b)” Younger people grew up speaking and writing in English so communication was another struggle that forced them to learn Spanish to continue their education. “…We didn’t understand Spanish. We didn’t know how to read or write it. We spoke a little Spanish, but not enough I don’t think. (Castaneda, 1972)” Valenciana also interviewed a young woman who left California at sixteen and her dreams to return to her birth place: “ I used to miss the states so much! I would cry every night because I was really lonely… I still had hopes of coming to my country. (Martinez-Southard, 1971)” The government sent away many of its citizens simply for the color of their skin.[63]

Though there was no federal act that demanded the deportation of Mexican-Americans and/or Mexican immigrants, there were local county relief centers. Instead of calling them deportation centers, legal counsels instead changed them from deportation centers to repatriation centers. Calling it repatriation insinuated that it was not forced deportation but rather a voluntary leave of the country. Most Mexican-Americans felt pressured to leave, with local government officials oftentimes going to the homes of Mexican immigrants and handing them train tickets to Mexico while telling them they’d be better off in Mexico. Many people believed it was right to deport the Mexican-American immigrant families in order for them to be with their own people in their own communities that spoke the same language as them and had the same traditions. It is estimated that around 60 percent of those who had been deported were actually American citizens.[64]

I’d like to thank my dedicated students who brought this chapter to life: Yaritzel Cuellar (Spring 2019), Sarea Couch, Anayeli Ledesma, Adam Izaguirre, Leonel Lizalde, Alejandra Lopez, Tatyana Marquez, Damian Mendez, Paulina Mosqueda, Jessica Figueroa, Luis Gonzalez, Jeason Pardo, Rory Harris, Ulises Ramirez, Alondra Roman, Destiny Vasquez (Spring 2020).

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Burton, Annie L., B. “Memories of Childhood Days.” New York: The Digital Schomburg, The New York Public Library. File number 1997wwm97252.sgm. 1997. http://digilib.nypl.org/dynaweb/digs/wwm97252/ ↵

- Pierce, Yolanda. "Her Refusal to Be Recast(e): Annie Burton's Narrative of Resistance." The Southern Literary Journal 36, no. 2 (2004): 1-12. http://www.jstor.org.libaccess.hccs.edu:2048/stable/20067786. ↵

- Digital History. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3390 ↵

- Overview: The conflict between religion and evolution. Last assessed February 3, 2014. https://www.pewforum.org/2009/02/04/overview-the-conflict-between-religion-and-evolution/ ↵

- What are Darwin’s Four Main Ideas on Evolution. Last assessed April 16,2018. https://sciencing.com/darwins-four-main-ideas-evolution-8293806.html ↵

- Clarence Darrow Biography. https://www.notablebiographies.com/Co-Da/Darrow-Clarence.html ↵

- An introduction to the John Scopes (monkey) trial. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/evolut.htm ↵

- An introduction to the John Scopes (monkey) trial. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/evolut.htm ↵

- William Jennings Bryan – Biography https://www.history.com/topics/us-politics/william-jennings-bryan ↵

- ‘Faith vs Fact’ https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/science-and-theology/2015/08/03/77136504-19ca-11e5-bd7f-4611a60dd8e5_story.html ↵

- Digital History. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3390 ↵

- Destiny Vasquez provided this content. ↵

- https://libguides.wustl.edu/Harlem-Renaissance ↵

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/21/the-man-who-led-the-harlem-renaissance-and-his-hidden-hungers ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- "Langston Hughes | Poetry Foundation". 2020. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/langston-hughes. Last accessed feb, 20, 2020 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Meltzer, Milton. Langston Hughes: a Biography. (New York: Harpercollins, 1988)isbn 0-690-0462-210 pg90 ↵

- "Langston Hughes | Poetry Foundation". 2020. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/langston-hughes. Last accessed feb, 20, 2020 ↵

- Meltzer, Milton. Langston Hughes: a Biography. (New York: Harpercollins, 1988)isbn 0-690-0462-210 pg74 ↵

- Rory Harris provided this content. ↵

- Janet L. Sims, Jessie Redmon Fauset (1885-1961): A Selected Annotated Bibliography, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2904406?seq=1 (Last accessed February 26, 2020) ↵

- Enter your footnote content here. ↵

- Jone Johnson Lewis, The Story of Jessie Redmon Fauset, https://www.thoughtco.com/jessie-redmon-fauset-3529264 (Last accessed February 26, 2020) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Laurie Champion, American Women Writers, 1900-1945: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, https://books.google.com/books?id=Qltu-Bw0hcUC&pg=PA101&dq=jessie+fauset+biography+&hl=en#v=onepage&q=jessie%20fauset%20hughes&f=false (Last accessed February 26, 2020) ↵

- Content provided by Jessica Figueroa. ↵

- http://blackhistorynow.com/james-weldon-johnson/ Last updated July 6, 2011 ↵

- “James Weldon Johnson Biography” https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/james-weldon-johnson-113.php Last Updated April 29, 2019 ↵

- Collier, Eugenia W. "James Weldon Johnson: Mirror of Change." Phylon (1960-) 21, no. 4 (1960): 351-59. Accessed February 22, 2020. doi:10.2307/273979. 4“James Weldon Johnson Biography” https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/james-weldon-johnson-113.php Last Updated April 29, 2019 ↵

- James Weldon Johnson Biography” https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/james-weldon-johnson-113.php Last Updated April 29, 2019 ↵

- "[Dedication: James Weldon Johnson 1871-1938]." The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 18 (1997): 1. Accessed February 22, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/2998717. ↵

- Corbould, Clare. "Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem." Journal of Social History 40, no. 4 (2007): 859-94. Accessed February 22, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/25096397. ↵

- Luis Gonzalez and Jeason Pardo provided this content. ↵

- “Independent Lens . BROTHER TO BROTHER . The Characters.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed February 22, 2020. http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/brothertobrother/characters.html. ↵

- Samuels, Wilfred D. “Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987) •.” •, September 4, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/nugent-richard-bruce-1906-1987/. ↵

- “Revolutionary Writer, Richard B. Nugent.” African American Registry. Accessed February 22, 2020. https://aaregistry.org/story/revolutionary-writer-richard-b-nugent/. ↵

- Alondra Roman provided this content. ↵

- https://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1989/1/89.01.05.x.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “The Harlem Renaissance” Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz [Online] Available https://www.jazzinamerica.org/LessonPlan/5/4/251 (Last Accessed Saturday, February 22, 2020) ↵

- “The story of Seattle’s Black and Tan club and those who owned it”, South Seattle Emerald; May 15, 2018 by Ashley Harrison. Available https://southseattleemerald.com/2018/05/15/the-story-of-seattles-black-and-tan-club-and-those-who-owned-it/ (Last Accessed Saturday, February 22, 2020) ↵

- “A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance” National Museum of African American History & Culture [Online] ; located at https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance (Last Accessed Saturday, February 22, 2020) ↵

- Nathan Irvin Huggins (Contributor Arnold Rampersad), Harlem Renaissance, (Oxford University Press, 2007) ↵

- “Hot Chamber Jazz: The Benny Goodman Trio 1935-1954”, River Walk Jazz ,2006, by Margaret Moos Pick. Available https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/hot-chamber-jazz-benny-goodman-trio-1935-1954 (Last Accessed Saturday, February 22, 2020) ↵

- Ulises Ramirez provided this content. ↵

- http://www.yehoodi.com/blog/2019/9/11/carl-van-vechten-on-lindy-hop-as-a-dance-craze-in-1930 ↵

- https://deyoung.famsf.org/deyoung/collections/multimedia/collection-icons-aspiration-aaron-douglas ↵

- Randy Dotinga “The second coming of the KKK” ↵

- Stanley Coben “Ordinary white protestants: The KKK of the 1920s” ↵

- Williams, Michael. “Carl Panzram: The Most Sadistic Serial Killer.” ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- PeoplePill. “Peter Kudzinowski: American Serial Killer ↵

- “FIVE EXPERTS CALL SLAYER NOT NORMAL; Only One Alienist Testifies Kudzinowski Is Sane as TrialNears Its End.” The New York Times. ↵

- Drexler, Paul. “Beastly Man Began Landlady Killing Spree in SF.” ↵

- Gaddis, Thomas E., and James O. Long. Killer: a Journal of Murder. ↵

- by Sarea Couch and Anayeli Ledesma ↵

- Getchell, Michelle. “The Presidency of Herbert Hoover (Article).” Khan Academy, Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/rise-to-world-power/great-depression/a/the-presidency-of-herbert-hoover. ↵

- Christine Valeciana, “UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEPORTATION MEXICAN - ERIC,” accessed February 22, 2020, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ759627.pdf) ↵

- Howard, Spencer. “Hoover on Immigration.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, hoover.blogs.archives.gov/2016/08/04/hoover-on-immigration/. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Valeciana, “UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEPORTATION ↵

- Gross, Terry. “America's Forgotten History Of Mexican-American 'Repatriation'.” NPR, NPR, 10 Sept. 2015, www.npr.org/2015/09/10/439114563/americas-forgotten-history-of-mexican-american-repatriation. ↵

- https://www.california-mexicocenter.org/the-u-s-deported-a-million-of-its-own-citizens-to-mexico-during-the-great-depression/ ↵