29 New Deal Era Culture, Race, and Gender

Culture 1930s

Jim Ross-Nazzal and Students

“They had to prove they were professional artists, they had to pass a needs test, and then they were put into categories—Level One Artist, Level Two or Laborer—that determined their salaries.”

-George Gurney, deputy chief curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2009[1]

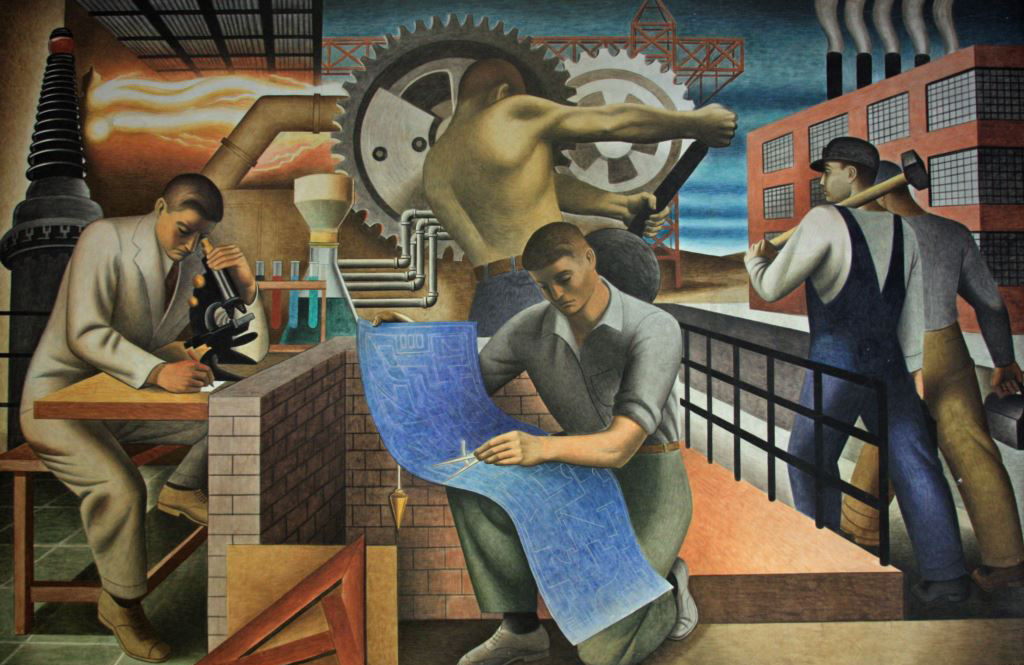

During the New Deal era (roughly 1933-1940), American culture, to include art, music, and Hollywood, spanned the gambit from realism (as in the painting above) to escapism (think Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Top Hat).

When people think about birth control they probably think about the Pill. What a powerful thing. The Pill. The Pill changed American society, politics, gender relations. The Pill. When you say “the Pill” everyone knows what you are talking about. And we have nothing else like it. There is no equivalent such as the tablet, the capsule, the lozenge, or the shot. People probably think about the power of the Pill changing American society only beginning in the 1960’s. In the 1930’s, contraception had become quite the profitable industry, exceeding $250 million in sales by 1938. “Fortune [magazine] pronounced birth control one of the most prosperous new businesses of the decade.”[2]

Art

During the Great Depression, the federal government got into the art business, such as the mural above which was commissioned by the Treasury Section of Fie Arts for the interior lobby of the original Social Security building in New York city.[3]

The artist, Seymour Fogel, said the images convey aspects of “national security” such as the scientist and “new frontiers,” the man at wheel who is in “complete control” of machinery, a man in the middle designing a future post-Depression and the men on the right seems to be closely overlooking the construction in the background.[4] According to the historian Barbara Melosh and Erika Doss:

Those depicted in Fogel’s murals were what can be considered white-collar professionals. Other artists, such as Arthur Murphy and Francis de Erdely painted blue-collar laborers. For example, Steel Riggers, No 4, Bay Bridge by Murphy in 1936.

Janet Bishop-Grant looked into Fogel’s career. Bishop-Grant took several of my history classes. This she researched and wrote in the Summer of 2021:

Seymour Fogel was an American artist who was best known for his modernist work during The Great Depression.[6] The Great Depression was a mid-century economic crisis that affected all; however, struggling artists and the future of public art were in severe jeopardy until the federal government used the Federal Emergency Relieve Act of 1933 to benefit them.[7] Fogel was one of those local artists that would benefit from what became the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and would become one of the most influential artists, based on his imagery of what rebuilding a nation looked like after the challenges from The Great Depression.[8] This essay examines who Seymour Fogel is and how he changed American history through art.

The PWAP was a federal work relief program that President Roosevelt appointed to Harry Hopkins and the purpose of this program was to assist struggling artists in making a living during The Great Depression.[9] Fogel was a local artist in New York that was employed under this federal program between 1935-1939 and was assigned to the mural division.[10] Murals completed by Fogel during this time period were displayed in the Social Security Building in Washington DC and his expression through art delivered a clear message; this struggle of The Great Depression is only temporary and the prosperity of the American people is near.[11] Fogel was considered a socially conscious artist, with his abstracted-realism style art and after his work in New York, he found himself as a teacher in the art department at the University of Texas at Austin.[12] His most famous works; “Security of the People” and “Wealth of a Nation”, Fogel illustrates how Americans will be able to indulge in leisurely activities again with a feeling of security and how important state planning is with the help of each entity working together for the benefit of the collective.[13] Other murals that Fogel painted during this time can be viewed at The Abraham Lincoln High School in New York and at the United States Custom Building as well.[14]

The purpose of Fogels’ art was to uplift and inspire a nation that did not see an end in sight during the economic crisis of The Great Depression. Fogel was motivating and his art gave communities around America hope and promise in themselves and in the federal government.[15] Still preserved today, his mural in the former Starr State office building in Austin exhibits a piece of “Texas modernist art that highlights the architecture of the building” and it shows how influential Fogel still is today, that art enthusiasts want to continue to preserve his legacy.[16]

A knock on these and other Depression-era artists take by modern historians is that their subjects overwhelmingly were white men. One well-known artist whose subjects were exceptions to the white men model was Diego Rivera. Rivera was a Mexican painter who came to the US in the early 1930s. While in Mexico his subjects were Mexican and indigenous peoples. In the US he painted numerous murals to include a 27-panel series for the Ford Motor Company in Detroit, Michigan. Here is one of those panels. You can see a mix of white and black men with at least one Asian person. The series is entitled Detroit Industry Murals and River painted them in 1933.

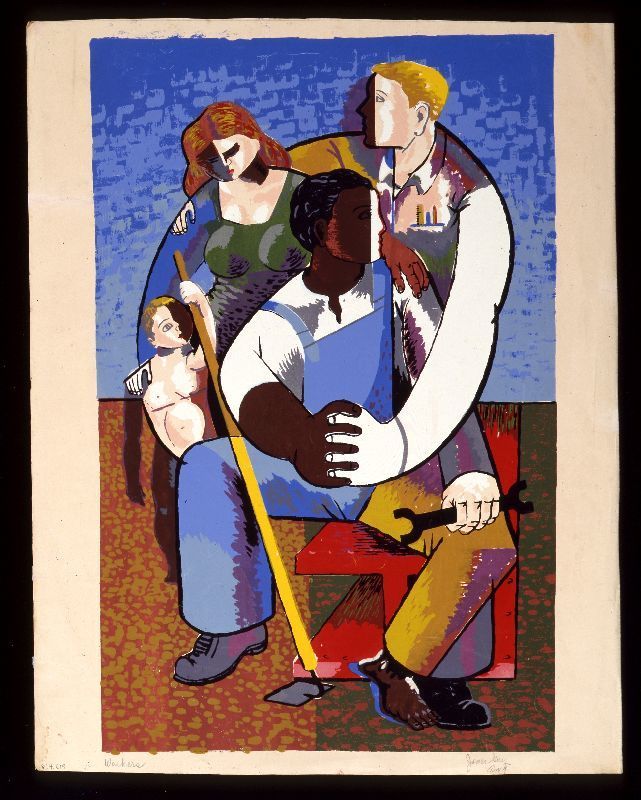

Another example of an exception to the image of the virile, muscular, industrious white male laborer was a painting called Workers by James Meikle Guy, Guy brought all sorts of elements together in his 1938 painting: male, female, blue-collar, white-collar, adult, child, black, and white.[17]

The federal government sponsored more than just paintings. It also got involved in the film industry, creating the United States Film Service. But whatever product was put out, “the artists themselves aligned with the New Deal . . . often a genuine reflection of enthusiasm for the government’s liberal agenda, as well as of gratitude.”[18]

And the government used the work of those artists to gain support for the government’s work as well as other reasons. For example, “Dorothea Lange’s images of government migrant camps were used . . . [to] undercut the opposition of California landowners” as well as showing the importance of those camps to the public.[19] Pare Lorentz made a film called The Plow That Broke the Plains “to demonstrate the need for soil conservation.” Support came from Rexford Tugwell, the head of the Resettlement Administration. Then he made a film, The River, in support of the Tennessee Valley Authority.[20] According to David Eldridge, “Lorentz both immortalized the TVA as a monumental and heroic undertaking and provided dramatic images to ‘prove’ its necessity.”[21]

President Roosevelt wanted two things in these federal cultural projects. First, he wanted the outcomes to include folklore, ethnic, local history and other kids of culture outside of established, Anglo-Saxon culture. Second, Roosevelt wanted the agencies to hire and give opportunities to non-white men. He saw these two as a way of demonstrating a major difference between Germany and the United States, what he called the “diverse local patters of thought and behaviour.”[22] Some of the underrepresented people who worked in the various New Deal agencies to produce examples of American culture included the Native American artists Stephen Mopope and Acee Blue Eagle; African American authors such as Theodore Brown and Hughes Allison and women such as Zora Neale Hurston.[23]

The Federal Theatre Project hired writers, directors, actors, set designers, and everyone needed to put on plays. The historian Colette Hyman noted that several themes were present in the plays of the 1930’s to include “community-based struggles, female leaders who both fit ans transcend conventional views of women, and the unity, however belated, between African American and White workers.”[24] These would all fit with Roosevelt’s “cultural democracy” idea.[25]

According to Loryn Lamonte, a Summer 2021 student:

Racism and claims of agitprop led to the end of the Federal Theatre Project. A four-year project funded by the Works Progress Administration provided work for theatre professionals and unskilled laborers alike during the great depression. Faced with constant backlash over the progressive topics often covered by their productions, people working in the Federal Theatre project became targets of red-baiting attacks from wealthy, racist conservative southerners. Black members often faced more censorship and attacks than the FTP’s white units and would have trouble getting many issues to the public.

The Federal Theatre Project was meant to provide entertainment and steady jobs to Americans as they fought to leave the great depression. It was also a bid to save the theatre industry, which was being phased out by movie theatres. Though the people part of this project held largely progressive points and values, segregation was still mandatory in the United States in 1935, so places like Seattle separated people into “white” units and “negro” units.[26] The topic of segregation in the FTP is important to note, considering the largely leftist beliefs people held in the Project. Live newspapers, which were productions covering current events, social issues, and issues considered taboo or controversial were produced for the American populace. Because live newspapers had communist origins, the Federal Theatre Project often had to tone their topics down from what they had originally wanted to do; however, that did not stop red-baiters from calling people in the FTP communist and socialist for the topics they covered.[27] Censorship was common among the black theatrical units. Many live newspapers were written and produced about issues concerning slavery and the treatment of African Americans was mostly shelved due to fear of backlash. Theatrical dramas made by the NTP discussed treatment and social issues for African Americans like Turpentine, Natural Man, and Big White Fog, which were written between 1936 and 1938, and outraged many racists. A live newspaper discussing the Anti-Lynching bill was created but eventually shelved due to the reaction of southern conservatives. The first live newspaper that got past the first draft stage in 1938 was written by Ward Vermont, and was called Stars and Bars; however, besides one review and call for revisions, there are no records on if it was performed or not. “Tyler concluded that the play had handled the living newspaper form ‘pretty well’- although his comments reveal that he himself did not understand the form.”[28]

The censorship that the Negro Theatre Project endured did not stop conservative racists to continue the call for extra censorship, creating more racist rhetoric, and did not end the constant claims of agitprop and socialist agenda that the FTP was apparently brainwashing the American public with. Radical conservatism was rising in the south during the 1930s. Southern Democrats did not like Roosevelt, did not like the new deal, and were the only major party in the south. Poor families were receiving jobs and benefits from the government, and southern democrats saw this as socialism and communism infiltrating the American government from the inside. Many southerners had a distaste for the Roosevelt family because of the help that they publicly gave to the black community. Many Texan racists, like Lewis Valentine Ulrey, believed that Russian specific communism was a Jewish conspiracy theory to destroy America by infiltrating churches, schools, and the Roosevelt administration themselves. These conspiracy theories are important because the men who would spread them were wealthy oil tycoons and politicians who had ties to the Ku Klux Klan and community. Groups of powerful men like Vance Muse, John Henry Kirby, and Ulrey gathered to spread racist and anti-Semitic rhetoric while also calling to push Communists away from Washington and the United States. While Kirby was careful to moderate his blatant racism to the public, he once wrote a letter to the author of Reign of Elders, “the most gripping comment on current events that I have read from any source. It is the greatest contribution to the current political literature of America that has been made…. This book has exalted my admiration for your patriotism and for the wholesomeness of your political philosophy.”[29] In 1938, the House Committee was called on by Congress to specifically investigate the Federal Theatre Project, and funding was depleted as they found the FTP to spread communist propaganda. On June 30, 1939, every worker for the FTP was issued a pink slip, and the project was officially disbanded.[30]

Radical conservatives were the main reason that the Federal Theatre Project was disbanded. Powerful southern racists saw the FTP as a communist/Jewish conspiracy theory, and they were successful at spreading racist and anti-Semitic propaganda. The NTP faced the most attacks in their endeavor to make their voices and history heard, even if many projects were shelved before they could happen due to the backlash that might ensue. The new deal was meant to pull American’s out of the Great Depression, and projects like the Federal Theatre Projects entertained over ¼ of Americans, even if it was not a long-lasting project funded by the Works Progress Administration.

The significance of this is that culture and New Deal politics were intimately connected.

1930s was the explosion of Big Band. Such was the likes of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey. And, New York was the center of the American music scene, but not for Earl Hines. Just before the stock market crashed, Earl Hines created his own band and began playing at the Grand Terrace Ballroom. Supposedly another music legend, Eubie Blake, told Hines to branch out on his own. Hines was a pianist but played unlike any other of his time. With his right hand he kept the melody and his left hand seemed to leave his body and play on plane beyond the terrestrial. Some music historians look to Hines as one of the pillars of modern jazz, at least the piano player of modern jazz. The music scene shifted from Chicago to New York as the 1920s became the 1930s. Hines wanted to head to New York. But Al Capone convinced Hines to remain in Chicago. Supposedly Capone owned the Ballroom, made a lot of money as long as Hines’ band was playing, and so Capone paid Hines more than any other band leader in Chicago. Not sure about the veracity of that nugget as Capone spent most of the 1930s in prison. Hines toured frequently in the 1930s and left the Grand Terrace Ballroom for good in 1940. “In 1934 Hines and his orchestra began live national broadcasting from the Grand Terrace and soon became the most famous jazz band on radio. Hines and his band also became the first to tour the South playing before mostly black audiences.”[31]

This is his obituary from the New York Times, April 23rd, 1983:

Earl (Fatha) Hines, the father of modern jazz piano, died Friday in Oakland, Calif., after a heart attack. He was 77 years old.

In his pioneering work with Louis Armstrong in the late 1920’s, Mr. Hines virtually redefined jazz piano. With what he called ”trumpet style,” Mr. Hines played horn-like solo lines in octaves with his right hand and spurred them with chords from his left. He thus carved a place for the piano as a solo instrument outside the rhythm section and defined the roles of both hands for the next generations of jazz pianists.

Mr. Hines’s strong right hand and angular melodic ideas continued to sound contemporary throughout his career. In the 1930’s and 1940’s, he led a Chicago big band that began the careers of the singers Billy Eckstine and Sarah Vaughan and included the saxophonists Wardell Gray and Budd Johnson. That band became an incubator for be-bop in the early 1940’s, when it featured the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and the saxophonist Charlie Parker.

Son of Two Musicians Earl Hines was born in Duquesne, Pa. His father was a trumpeter and his mother played piano and organ. He took up the trumpet as a child, but began studying classical piano at the age of 9. After three years of lessons, he decided he was more interested in jazz piano, and by the time he was 15 years old he was leading his own trio.

Mr. Hines worked with big bands led by Lois B. Deppe in Pittsburgh and Carroll Dickerson and Sammy Stewart in Chicago, and in 1927 he joined a quintet led by Louis Armstrong at Chicago’s Savoy Ballroom.

With Mr. Armstrong, he made such recordings as ”West End Blues” and ”Weather Bird,” and in 1928 he recorded solos, including ”A Monday Date” and ”Caution Blues,” that established his style and have had a lasting influence on jazz piano.

Mr. Hines started his own big band in 1928 at Chicago’s Grand Terrace Ballroom, and stayed in residence there for more than a decade, although he toured for part of each year. His was one of the first black big bands to tour the South.

The band recorded his best-known composition, ”Rosetta,” and had hits with Mr. Eckstine’s vocals on ”Jelly Jelly” and ”Stormy Monday Blues.” Although he left the Grand Terrace in 1940, Mr. Hines led a big band nearly continuously until 1947; at one point the group included an all-female string section.

Origin of Nickname A Chicago disk jockey called him ”Fatha” in the 1930’s and the nickname – as in ”Father of modern piano” -stayed with him.

After dissolving his band, Mr. Hines worked with smaller groups. He rejoined Mr. Armstrong from 1948 to 1951, then led his own groups.In 1957, he toured Europe with an all-star group including the trombonist Jack Teagarden; in 1966, the United States sponsored Mr. Hines’ group on a tour of the Soviet Union.

Since the 1950’s, Mr. Hines had been based in the San Francisco Bay Area, and he continued to tour Europe, Jpana and the United States. His most recent New York engagement was in August 1982 and he appeared in San Francisco last weekend.

It is believed that Mr. Hines is survived by a granddaughter. He was divorced from his wife, Janie, in 1980.[32]

Gangster movies were wildly popular in the 1930s. Early on, it was the gangster with his glamorous lifestyle and the bumbling cop, while later in the decade the law won out over those gangsters, who were either sentenced to prison or met their end in the electric chair. Through gangster films, Americans were introduced to “slang, non-standard English, and ethnic, regional and class dialects.”[33] For example, in the prison movie The Big House (1930), Machine Gun Butch Schmidt (played by Wallace Beery), looking at a photo of Kent’s sister, says to Kent Marlowe (a very young Robert Montgomery): “Gee… it reminds me of Sadie. Gee, Sadie was a good skirt. I shouldn’t have slipped her that ant poison. I should have just battered her in the jaw a few times.”

Then on the opposite end of the drama and death of crime and gangster films was the craziness of the Marx Brothers. In the film, Animal Crackers, Groucho played a supposedly famous African explorer name Captain Geoffrey T. Spaulding. His financier, and the butt of many of his jokes, Mrs Rittenhouse played by Margret Dumont, threw a parry for him. Groucho was late. When he did arrive, he did so in song and which made little sense:

Groucho: “Hello, I must be going! I came to say I cannot stay, I must be going. I’m glad I came but just the same I must be going.”

Margret Dumont: “Oh my friend, you must stay. For if you go away, you’ll spoil this party I am throwing.”

Groucho: “I’ll stay a week or two. I’ll stay the summer through. But I am telling you, I must be . . . going.”

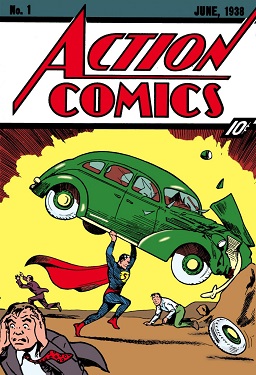

Comic books exploded on the scene in the 1930s. Comics were not a twentieth century invention, of course, but the mass consumption of comic strips, magazine, and books as well as tie in to movies was new and quite lucrative. “The word was spreading through the printing and pulp business: There was money to be made in comics.”[34] Comics strips in newspapers were the first form of movies translated onto print. And the first movie star to be seen in newspaper was Micky Mouse on January 13, 1930.[35] Magazines and books followed comic strips and those books and magazines were sometimes released before the movies they portrayed were released. Other times the comic books came out after the movies. For example, a publisher called Big Little Books adapted westerns such as The Fighting Code, Gun Justice, and The Big Cage.[36] Big Little Books also took story lines from comic strips, such Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, and Little Orphan Annie.[37]

Not all comic books were what we would consider or know to be “comics” today. In the 1930s Jumbo Comics published Stars on Parade which featured famous movie stars such as Katherine Hepburn and her hats, and the the comedian/ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy.[38] And then there was Action Comics. Action Comics #1 also featured a movie star: Fred Astaire. In addition, Action Comics #1 introduced Superman to the world.[39]

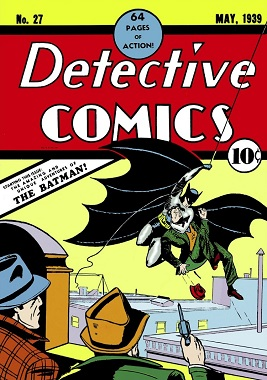

There was money to be made in the comics. But the industry was volatile. Companies issued just a few editions and then folded before ending the storyline. One of the more successful comic publishing companies that emerged from the 1930s was established by Martin Goodman. He called his company Marvel Comics. The Human Torch was in the first issue of Marvel Comics. Today Marvel Comics include Captain America, the Hulk, Spider Man, Iron Man, Black Panther, the X-Men, Silver Surfer, and Captain Marvel, to name a few. At that same time, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson established National Allied Publications. One of the comic book series he published was Detective Comics, or DC. DC introduced Batman to the world (their first hit) in Detective Comics #27 in 1939.[40]

Coming Soon: Radio from Little Orphan Annie to War of the Worlds.

Eleanor Roosevelt was an icon. A cultural icon. An icon of the Civil Rights era. An iconic First Lady who in great measure carved the First Lady’s position away from that of mere hostess. Students Erika Portillo, Esmeralda Rodriguez, Gonzalo Salas, Raul Sanchez, Lam Thuy Van Tran, and Flower Torres looked at some of the facets of the longest-serving First Lady

Eleanor Roosevelt was well known for her role in advocating for the human, worker, and civil rights after The Great Depression. This depression caused several issues such as poverty, the wiping out of millions of investors, culture, and labor difficulties. Roosevelt did many things to combat these issues by involving herself more than other people in power would have been. She would then continue to be the First Lady to hold press conferences to address issues in a public manner.

As First Lady in 1933, Roosevelt decided to hold the first-ever women’s only conference. Before this time, First Ladies had little contact with reporters. Roosevelt recognized that holding regular conferences could enhance the public role of the First Lady – a role she transformed during her twelve years in the White House.[41] She held these conferences regularly and spoke on topics such as domestic issues, international politics, female leaders, and women’s roles were discussed amongst the many respectable women during these conferences. This kind of platform would then be used as a way to not only discuss but find solutions to a great many issues of workers, human, and civil rights.

Later in 1934, Eleanor Roosevelt joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, NAACP, to advocate for African Americans. For example, Eleanor Roosevelt and members of the NAACP such as Walter White wanted to lobby for President Roosevelt and members in Congress for legislation to prohibit lynching throughout the United States.[42] During this time period, there was a lynching problem throughout the country because mainly African Americans were lynched by white Americans. For example, Claude Neal was an African American that was arrested for the murder of a white woman. He was then abducted by a mob of white Americans and lynched a few hours later.[43] In response to the lynching incidents, Eleanor Roosevelt showed support to the Costigan Wagner Anti Lynching Bill, which made it a crime for any law enforcement officer to exercise their responsibilities, during a lynching incident. Roosevelt and White continued to persuade the president throughout 1935. However, the president did not support the bill because he was afraid of losing the support of the South.

In 1936, Roosevelt became famous for her daily newspaper articles, most of which challenged society’s wrongdoings, supported human rights, and demystified women’s roles, thus ensuring that she made a name that was distinctly separate from that of her husband. She became famous for supporting working women, which almost surpassed her previous commitment of lobbying for women’s participation as voters, and appointments to party and department leadership positions. To popularize her position and influence change, she began writing a daily syndicated newspaper column titled “My Day” in 1936.[44] The column appeared in the newspaper six times a week and was considered one of the most influential factors driving leadership change among American women. In the column, Eleanor wrote about her daily activities, as well as her humanitarian concerns. Ideally, writing about her daily activities made it possible for her to demystify the notion held by the American society for women’s roles, which were largely centered around taking care of their families and completing domestic duties. To this end, she was able to demonstrate that women too could play a significant role in leadership and influence their societies’ welfare.

In her daily syndicate newspaper, “My Day,” Roosevelt states, “The even more fundamental task that lies before the leader is to bring to the people the realization that true democracy is the effort of the people individually to carry their share of the burden of government.”[45] She believed that leadership is not all about creating opportunities for the citizens, but rather empowering them to realize these opportunities themselves and exploit for their benefit, and those around them.

Furthermore, articles made it easy for American men to appreciate and support women in leadership as they sought to create a more accommodative society. On the other hand, sharing her humanitarian concerns in the column made it possible for her to improve the public’s awareness concerning human rights and American’s welfare.[46] For instance, it made people aware of their right to fair governance and enabled them to fight against any authority that attempted to violate such rights. As a result of her efforts, business and political leaders became more responsive to the American’s rights and freedoms, enabling them to guarantee citizen’s welfare.

In 1939, Howard University, School of Music in Washington DC would request the Constitution Hall for a concert, which was considered the largest auditorium in the capital. Marian Anderson, who is an African American, toured the United States and sang annual concerts for Howard University. The annual concerts that she performed were so successful that each year they had to find a new venue to accommodate larger crowds. However, Anderson was denied performing in the venue because of her race.[47] Mrs. Roosevelt personally knew Anderson when she was invited to perform at the White House. In her response, Roosevelt used the newspaper column “My Day” to announce her resignation from the Daughters of the American Revolution for discriminating against Anderson to perform on the venue. Afterward, the President gave his approval for Anderson to perform at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday. Due to the enormous amount of attention that would be drawn to the First Lady, she chose not to be publicly associated with the sponsorship of the event. However, she persuaded various radio networks to broadcast the concert to the public. The performance gathered seventy-five thousand people, including dignitaries and average citizens. The performance had a very diverse crowd which included black, white, old, and young people dressed in their Sunday finest.[48] The opening song was “America”, and her final song was “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen”.[49] This event was a life-changing event due to the attention it brought to the country’s color barrier.

One of Roosevelt’s main passions was working hand in hand with advocates from the Civil Rights movement after the Great Depression. Many African Americans were still suffering from the effects of the depression, with 70 percent of African Americans in Atlanta being unemployed at the time, in comparison to 25 percent of white workers unemployed.[50] One of the people the First Lady was in contact with A. Philip Randolph, a great protestor against racial discrimination, especially in the workforce. Roosevelt promptly became a supporter of Randolph’s cause, and in 1941 arranged a meeting for him and FDR at the oval office. In this meeting, Randolph brought up his idea to create a massive march to Washington in efforts to end racial discrimination. In efforts to de-escalate the problem, FDR agreed to sign an executive order to create the Fair Employment Practice Committee, which outlawed discrimination against African Americans in the military industry. With this, we can see the role Roosevelt played in creating a common ground between those trying to have their grievances shown to those with the most power in the matter, in this case, FDR.

Roosevelt was well known for her role in advocating for workers, human and civil rights. She also used her role as the First Lady to promote the rights and liberties of Americans. Supporting African American in their Civil Rights would gain support from the NAACP. Also, giving insight to many Americans with her daily newspaper, “My Day”, in influencing Americans that women have a role in leadership, promoting for American welfare, and warning businesses of violating any of their worker’s rights.

Marian Anderson[51]

Marian Anderson, a contralto singer, was born on February 17th, 1897 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was the oldest of three daughters. John Berkeley Anderson and Anne were her parents, a hardworking middle-class couple. Her grandparents were freed slaves from Virginia. Her passion for music started at a young age as she started singing in the choir of the church she used to go with her family when she was six. As mentioned in the abstract from “Anderson, Marian” by Handy, “When Marian was about eight her father purchased a piano from his brother; she proceeded to teach herself how to play it and became good enough to accompany herself.”[52] Her father died when she was only twelve, her mother did not make enough money from her job and they started to live in severely straitened circumstances. Nevertheless, Anderson continued singing at different churches and she was well-known for her talent and performances within the black community. However, she was not covered by white newspaper because of racism that was still prominent during that time.

As Teachout said, “In 1927 she used her savings to go to Europe, searching for teachers who could pull her out of her provincial rut. In Europe her race was mainly seen as a novelty rather than an impediment, and she slowly began to win critical acclaim.”[53] It was in the same year when she started to establish as a solid singer with international fame, more specifically, in Europe, known for her emotionally timbre. Upon returning to the U.S. with more experience and with the help of the recognize American manager, Arthur Judson, she still struggled to perform as a concert artist in opera houses because of her race. She continued her studies in Europe, earning a place as one important artist in classical music. She demonstrated that racial hierarchy and racism were not limiting but rather limited.

In 1939, an unpropitious event put her and the U.S. politics into the international spotlight. In accordance with Vriend-Robinette[54]

Marian Anderson, world-renowned contralto, was scheduled to sing at Constitution Hall, which was owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Because of their discriminatory policy allowing only white performers, she was barred from singing in the hall. Marian Anderson was African American and did not meet the DAR’s criteria. (24)

As a result, the U.S. was recognized across the world as a racist country. After all the controversy, the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR. With the help of the first lady and president Franklin D. Roosevelt, Anderson performed in an open-air concert on April 9th, 1939 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. in front of an audience of more than seventy-five thousand people. As mentioned by Vriend-Robinette, “Marian Anderson became an important symbol demonstrating simultaneously the need for African American empowerment and the ability of African Americans to attain a significant level of success within the U.S. culture.”[55] At that moment, she became an icon and the voice of the black community in their struggle for racial equality and civil rights.

According to Teachout, “Anderson had one last triumph ahead of her. Rudolf Bing, (…) who took over the Metropolitan Opera in 1950, was determined to break the company’s color bar, (…) he contracted with Anderson for her first stage role.”[56] This action made her the first black person to perform at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC, with her presentation as Ulrica in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera.

More than a singer, Marian Anderson was an African American woman who broke every barrier in her pursuit of success. Not only she became an icon for her talent as a singer, but her willingness to help the minority, more specifically, the African American community, who were discriminated against for their skin color. Her life was significant and important in the history of the U.S. for every person who felt underestimated and for whom she fought for their civil rights, and racial equality. She had to go through so many restrictions to become a respected artist in her own country that her actions made her a representation of all those who suffer inequality and, ultimately, she became a symbol in the community for their fight against racism.

A big thank you goes to Erika Portillo, Esmeralda Rodriguez, Gonzalo Salas, Raul Sanchez, Lam Thuy Van Tran, Flower Torres, Loryn Lamonte, Janet Bishop-Grant, and Cynthia Romero for their dedication and insights.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/1934-the-art-of-the-new-deal-132242698/ ↵

- Andrea Tone, "Contraceptive Consumers: Gender and the Political Economy of Birth Control in the 1930s," Journal of Social History, Spring 1996, p. 485. ↵

- Erika Doss. "Looking at Labor: Images of Work in 1930s American Art," Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, 2002 Vol. 24, p. 230. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., and Barbara Melosh, Engendering Culture: Manhood and Womanhood in New Deal Public Art and Theater (Washington DC: Smithsonian Press, 1991) pp. 88-89. ↵

- Russel Tether, “Seymour Fogel and the art of American Optimism”, Russel Thether Fine Arts Associates, LLC, 2013, https://russelltetherfineart.wordpress.com/2013/01/05/seymour-fogel-and-the-art-of-american-optimism/ (Accessed July 24, 2021). ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Judy Telford Deaton, “Seymour Fogel: On The Wall and Beyond”, The Grace, https://www.thegracemuseum.org/exhibitions-list/2015/5/28/seymour-fogel-on-the-wall-and-beyond. (Accessed July 24, 2021). ↵

- Ibid ↵

- The New York Times, “Seymour Fogel is Dead at 73; Artist Created Public Works”, The New York Times 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/08/obituaries/seymour-fogel-is-dead-at-73-artist-created-public-works.html. (Accessed July 24, 2021). ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Texas Commission on the Arts, “Seymour Fogel Mural”, Texas Commission on the Arts, https://www.arts.texas.gov/initiatives/public-art/seymour-fogel-mural/. (Accessed July 24, 2021). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- David Eldridge, American Culture in the 1930's (Edinburgh University Press, 2008) p. 164. ↵

- Ibid., p. 166. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., p. 167. ↵

- Ibid., p. 172. ↵

- Ibid., pp173-174 ↵

- Colette Hyman, "Women, Workers, and Community: Working-Class Visions and Workers' Theatre in the 1930s," in Canadian Review of American Studies, Fall 1992, Vol 23, Issue , p. 15. ↵

- Eldridge, America Culture, p. 173. ↵

- P.Scott Corbett, et al. “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1941” in U.S. History. OpenStax, Rice University. Pg. 784. ↵

- HCC History Faculty, Bryan Burrough. American Perspectives, Readings in American History Vol. 1, “Birth of the Ultraconservatives.” Pgs. 344-352. ↵

- Paul Nadler. "Liberty Censored: Black Living Newspapers of the Federal Theatre Project." African American Review 29, no. 4 (1995): 615-22. Accessed July 23, 2021. Pg. 617. ↵

- HCC History Faculty, Bryan Burrough. American Perspectives, Readings in American History Vol. 1, “Birth of the Ultraconservatives.” Pg. 347. ↵

- Paula Becker. ”Federal Theatre Project.” HistoryLink.org, 2002. https://www.historylink.org/file/3978. Accessed July 23, 2021. ↵

- https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hines-earl-fatha-1903-1983/ Last accessed 4 AUG 2020 ↵

- https://www.nytimes.com/1983/04/23/obituaries/earl-hines-dead-top-jazz-pianist.html (Last accessed 4 AUG 2020) ↵

- Aaron Baker, "1930 Movies and Social Difference" in American Cinema of the 1930s edited by Ina Rae Hark, p. 27. ↵

- Blair Davis, Movie Comics: Page to Screen. Screen to Page, Rutgers University Press, 2017. p. 69. ↵

- Ibid., p. 56. ↵

- Ibid., p. 63. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 67-68 ↵

- Ibid., p. 68. ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detective_Comics_27 (last accessed 1 AUG 2020) ↵

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, March 6, 2014, https://fdrlibrary.tumblr.com/post/78751510597/eleanor-roosevelts-first-press-conference-march ↵

- “Eleanor Roosevelt's Battle to End Lynching.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2016/02/12/eleanor-roosevelts-battle-to-end-lynching/. ↵

- “Eleanor Roosevelt's Battle to End Lynching.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed November 26, 2019. https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2016/02/12/eleanor-roosevelts-battle-to-end-lynching/. ↵

- Marsh, John. Emotional life of the Great Depression. (New York: Oxford University Pres, 2019), 188-189. ↵

- Roosevelt, Eleanor. "My Day." Raleigh News Observer (February 17, 1938) (1939). ↵

- Kerber, De, Dayton, & Wu. Women's America: Refocusing the past. (New York: Oxford University Press), 553. ↵

- “The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Advanced Placement United States History Study Guide.” Eleanor Roosevelt as First Lady | AP US History Study Guide from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, March 12, 2013. http://ap.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/new-deal/essays/eleanor-roosevelt-first-lady. ↵

- “Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson.” FDR Presidential Library & Museum, n.d. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/anderson. Accessed December 3, 2019 ↵

- “Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson.” FDR Presidential Library & Museum, n.d. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/anderson. Accessed December 3, 2019 ↵

- Klein, Christopher. “Last Hired, First Fired: How the Great Depression Affected African Americans.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, April 18, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/last-hired-first-fired-how-the-great-depression-affected-african-americans. ↵

- By Cynthia Romero, one of my students, Fall 2019 ↵

- Handy, Antoinette. “Anderson, Marian.” American National Biography Online, Oxford University Press, 2000. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1803320. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019. ↵

- Teachout, Terry. “The Soul of Marian Anderson.” Commentary, vol. 109, no. 4, Apr. 2000, p. 53. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=2939298&site=eds-live. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019. ↵

- Vriend-Robinette, Sharon R. Marian Anderson as Cold Warrior: African Americans, the U.S. Information Agency, and the Marketing of Democratic Capitalism. Vol. 57, no. 4, 2019, pp. 23–47. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edspmu&AN=edspmu.S2153685619400017&site=eds-live. Accessed 18 Oct. 2019. ↵

- Vriend-Robinette, Sharon R. Marian Anderson as Cold Warrior: African Americans, the U.S. Information Agency, and the Marketing of Democratic Capitalism. Vol. 57, no. 4, 2019, pp. 23–47. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edspmu&AN=edspmu.S2153685619400017&site=eds-live. Accessed 18 Oct. 2019. ↵

- Teachout, Terry. “The Soul of Marian Anderson.” Commentary, vol. 109, no. 4, Apr. 2000, p. 53. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=2939298&site=eds-live. Accessed 15 Oct. 2019. ↵