23 Populism: Questioning the Relationship Between the Governed and the Government, 1870s-1900

And Baseball

Jim Ross-Nazzal and Students

“Don’t make me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.” -Dr. Bruce Banner (aka the Incredible Hulk)

The country tended to be Jeffersonian in the sense that government was best taken care of at the local level, that federal government could trample individual liberties, and that the relationship between the governed and the government was one of disinterest at best or mistrust at worst. But due to the depression of the 1870s, Congress taking the US off the bimetallic standard, and the rise of the power of railroads, some Americans began to rethink the relationship between the government and the governed. Farmers were the first group to react against what they believed to be injustices eventually forming a political party known as the Peoples’ Party of the Populist Party.

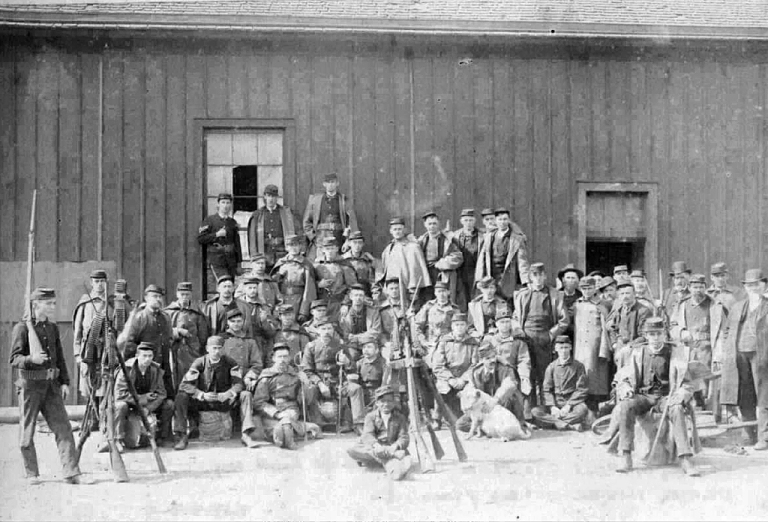

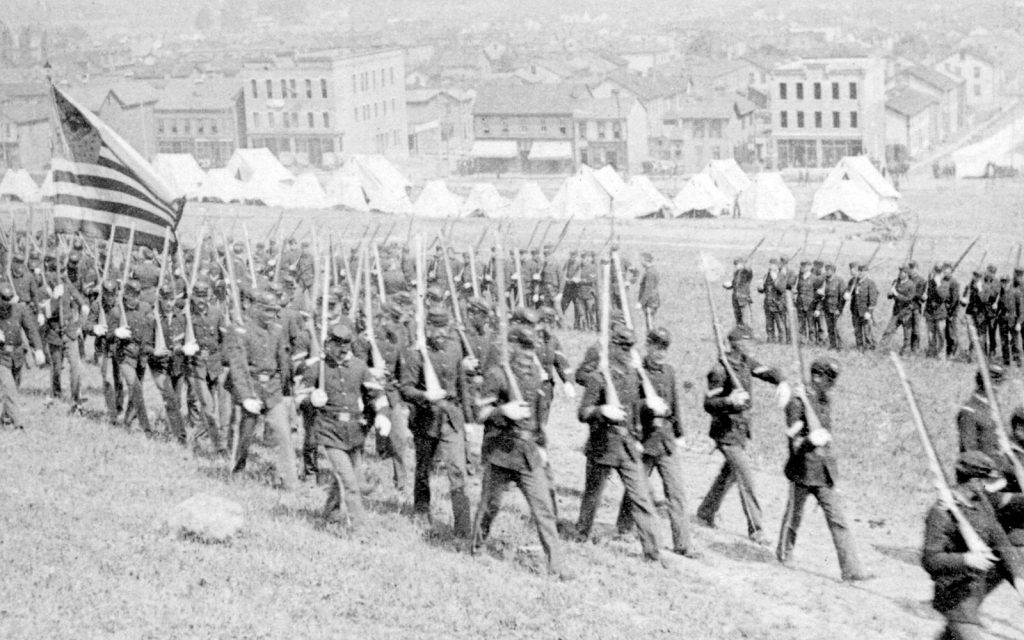

And the railroad was one of the villains. Railroads were hurt by the 1873 depression so many cut wages.By July of 1877, B&O experienced their third wage cut of 10%. Workers in West Virginia stuck. The strike spread and violence followed. State militias were called out in Pennsylvania but would not fire on workers so President Hays sent out federal troops, who did engage the strikers. Thus setting up the pattern of strike-military-violence which was endemic in the Gilded Age.

For example, in Bay View section of Milwaukee, Wisconsin striking Polish iron workers, with support of the local Catholic church, closed the foundry. The military shot and killed 20 strikers. A company town in suburban Chicago, Pullman made railroad cars. The owner cut wages by 40% while increasing rent, utilities and food in the company town. Workers struck. The US Attorney General argued that the US mail was affected by the strike and had union leaders (like Eugene Debs) jailed. Troops were sent in and the court used the Sherman Anti-Trust Act against Debs, union leaders, and unions themselves.

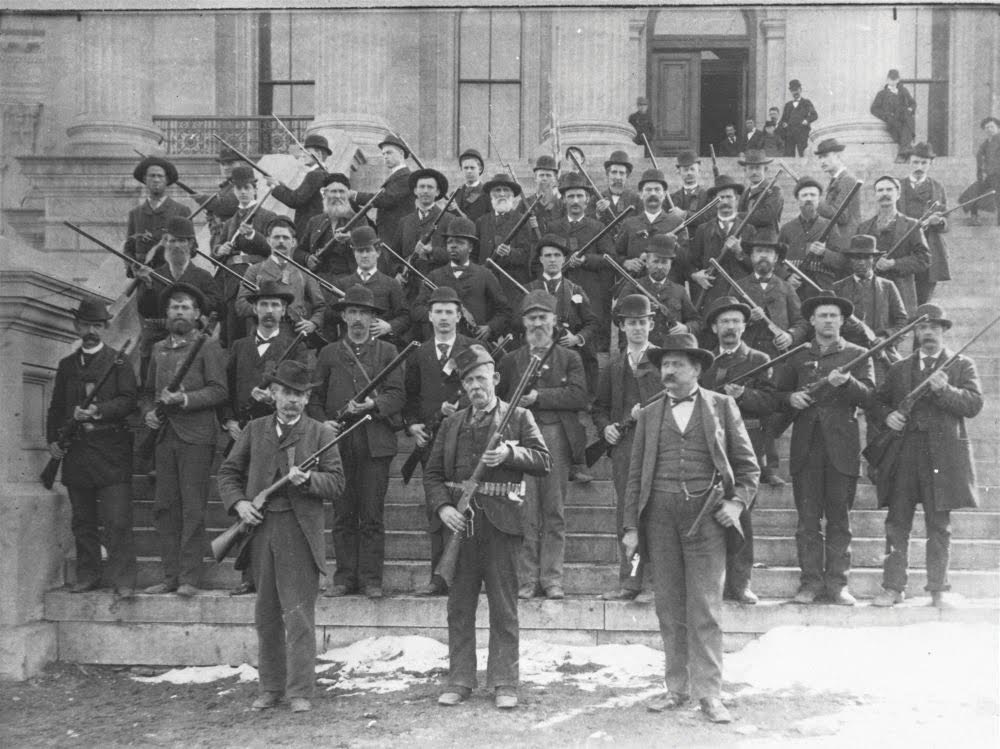

But the most famous (infamous) act of violence against strikers was in Homestead, Pennsylvania. The government’s reaction was not just to break the trike but to quell the growth of labor unions. Andrew Carnegie accepted the existence of union, initially, due to the huge demand for his steel. But when the old contract expired, Carnegie’s man on the ground, Henry Frick, cut wages. When the strike began Frick had a stockade built and hired a private security form -the Pinkertons- to put down the unrest. The gun battle between the armed strikers and the Pinkertons lasted for four days, at which point the governor called in the National Guard. The combined fire power of the Pinkertons and the Pennsylvania National Guard broke the strike.

But it was farmers who came together to challenge the status quo politically. This chapter is primarily about an agrarian response to the Gilded Age.

The 1860’s saw agrarian protests about the prices farmers were receiving at market as well as transportation costs. There were problems in h rise of an international market. The sharecropping or lien system put families further into debt. Western farmers were particularly affected because of their reliance on a single crop and finally farmers were subject to vagaries of nature and debt. Middle Class reformers like Edward Bellamy worked with farmers, but to no avail.

People reached out to their government. For example, a Minnesota girls wrote a letter to her governor in 1874 telling him that the family had no money, that grasshoppers destroyed their crops, they have no team to plow and own only two quilts to keep warm (they had no money to plaster the house). She asked the governor to send wool or money. In 1893 a Kansas women wrote to her governor saying that the family was starving to death, her husband could not find any work, and that she was pregnant.

During the Civil War, the country’s political parties decided to accept the idea that progress reflected economic production, thus industrialists (not agrarians) led the mindset of each party.

The money question was about who issued it, how much would be in circulation, backed by gold or silver or both, and should there be paper money in circulation (and should the paper money be backed by precious metals)?

During the War, the federal government issued paper money which as not backed by gold (around 450 million greenbacks were in circulation). This led rise to inflation, greater commercial liquidity and the general prosperity rose (buying and loaning power). Not being on the gold standard helped those who borrowed money, such as farmers.

Those national banknotes were redeemed over time, thus diminishing the supply. And specie coins, were minted with 16 parts silver to 1 part gold.

Conservatives wanted to see a contraction of the money supply. Inflation was not good for creditors and those “gold bugs” wanted to return to the gold standard. As long as the federal government kept printing and circulating paper money, the economy was stable and both helped farmers. But in 1873 the silver market fell and Congress responded by stopping to coin silver, thus the economy contracted even more and by 1879 the US was back on the gold standard, which meant the economy contracted even more. All of this was good for those who loaned money (bankers and Wall Street investors) but bad for those who borrowed money (farmers).

So, the money supply contracts but the population and production increase and farmers quickly lost money. For example, say farmers were getting $1 for each bushel of wheat but after going back on the gold standard farmers were into getting $1 for many bushels of wheat. Good for consumers but very bad for farmers. Grains as well as dairy and eggs dropped in price.

Farmers argued that as long as everyone accepted the value of greenbacks, the money system did not have to be tied to gold. In other words, there could be no intrinsic value to the greenbacks. This is what we have today. A $5 bill is worth five dollars because we collectively agree that is the case AND the international markets (and consumers) agree.

So, silver is demonetized by Congress in 1873. Farmers called it the “Crime of ”73.” Lots of silver in the market place (silver mining was very successful), and if coined would be cheaper than gold but f redeemed it would get less than gold. Well, Jay Cooke’s investment bank collapses taking the economy with it, resulting in a depression. Farmers and laborers call for a return to the coinage of silver. And so . . .

Populism Begins

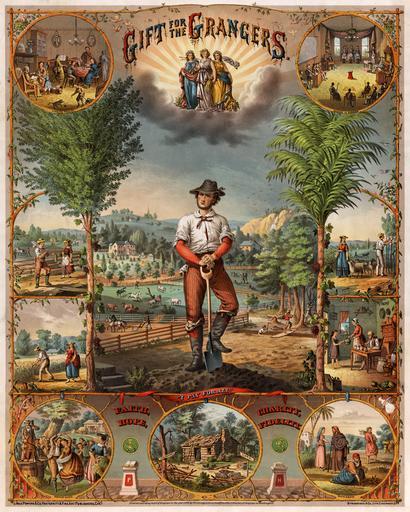

Texas had a lot of disgruntled farmers: southern farmers often moved to Texas when they lost their farms in the South and so it’s not surprising that in Texas farmers coalesced to form social and political groups such as the Grange, also known as the Patron of Husbandry. The Grange started off as a social group (about 1.5 million members by 1875) but eventually promoted cooperatives.

The Grange purchased and sold farm necessities together (they could get better deals) but quickly became political due in part to the uncertainty of railroad rates. Farmers never knew how much their transportation costs were going to be because there was not a standard, national shipping rate. Midwest states passed “Grange laws” to regulate transportation rates. Railroads took the Granges to court, eventually going all the way to the Supreme Court. In Munn v. Illinois (1877) the Court fond that states had the right to regulate railroad rates. Thus the Grange was successful in regulating railroad rates in some states.

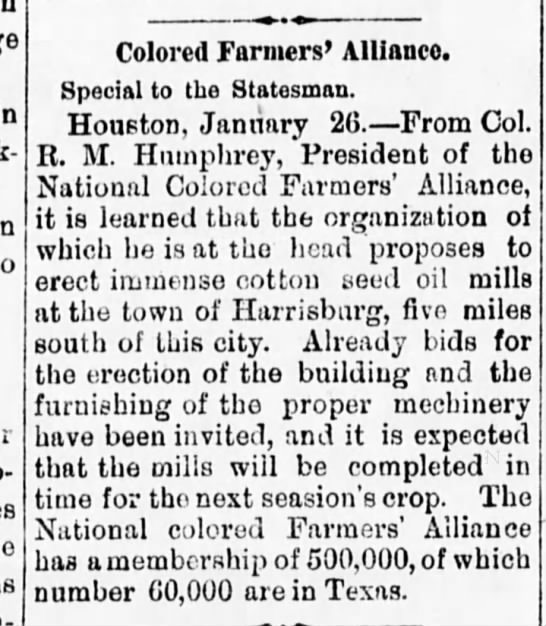

While the Farmers’ Alliances were political factions. Grange membership dropped in the 1880s in part because nature was kind and the political arms started taking over. The Texas Alliance emerges at this time as a full-blown movement. Midwest Farmers’ Alliances come together in tandem with the Colored Farmers Alliance. And the zealous leaders recruited. Not just rural as many understood labor to be their peer -the producers- as opposed to non-producers (managers/administrators).

Remember, the Knights of Labor won bargaining as a weapon, however Gould crushed them in the 1886 strike in Texas. The Texas Farmers Alliance supported the Knights of Labor with the view of recruiting laborers into their movement. So farmers boycotted the railroad, gave food to strikers, attended Knights of Labor union meetings. This might have been a radical move as the Farmers Alliance left the Jeffersonian ideal of the yeoman farmer for direct political action.

In 1886, at a meeting in Cleburne, Texas, the Texas Farmers Alliance issued the “Cleburne Demands” to politicians and the public. The “Demands” had 17 planks, just like a political party’s platform. They reissued their support of labor and from those “Demands” three significant issues emerged: transportation, land and money.

Under transportation, the farmers wanted “real” valuation of railroad stock (no more watering of stock) and an interstate commerce law to regulate railroad rates.

Farmers wanted the federal government to tax land speculators as well as to not sell land to speculators anymore. They wanted the railroads to sell federal land to farmers and pioneers, and, showing a touch of nativism, aliens would be prohibited from owing land in the US.

And, the federal government needed to support a national banking system with flexible currency; unlimited coinage of silver and gold and the use of hard currency to retire the national debt. But, there was some dissension, fearing demands were too socialist. On the other hand, some believed the demands did not go far enough, such as Charles Macune.

In Waco, Texas, 1877, Charles Macune proposed to a meeting of the Texas Farmers Alliance a statewide coop. a “farmers’ exchange.” A central purchasing and selling mechanism. He also wanted to see all southern alliances merge into a regional force. The group approved of his proposals and decided to send messengers out to publicize and educate; akin to missionaries.

These and other ideas (and people) from Texas migrated north to Kansas. The Kansas Farmers Alliance trained and developed lecturers and developed a Farmers Alliance culture that differed from the general South. For example, Kansas tended to be more Republican and the general South was Democratic.

Meanwhile, in the 1880’s and 1890’s, Farmers Alliances from the North and Midwest started joining the South Farmers Alliance creating the “National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union,” which fed naturally into the forthcoming Peoples’ Party, or Populists.

But could a coop commonwealth co-exist with banks? In Texas, they said “no.” Banks could not loan money to the Texas Farmers’ Alliance so the Texas Farmers’ Alliance started their own bank, which failed due to other banks refusing to loan money or accept their notes. So . . .

In 1889, Charles Macune came up with the idea of the “subtreasury.” The subtreasury was about storage and borrow. The government would build warehouses or “subtreasuries” to store crops until the best prices were realized. While the farmers’ crops were waiting for sale, farmers could borrow up to 80% of the estimated value of what was stored at only 2% interest.

However, there were cracks in the armor of the movement. First, northern Farmers’ Alliances wanted to include black farmers while the southern Farmers’ Alliance wanted to exclude black farmers. Race clouded the movement in the South. Eventually black farmers created the Colored Farmers’ Alliance. Second, not all farmers wanted to recruit labor as they saw the needs of the farmers too divergent from the needs of labor as well as a rural (farmers) versus urban (labor) thing. And in reality the Farmers’ Alliance had a very difficult time bringing labor into the movement out of labor’s intransigence. Third, some were too tied to the established political parties to establish a political party. It’s difficult to walk away from the party of their fathers. Finally, the white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestants in the South were concerned about the Catholic and ethnic population of the North (those new immigrants).

An interesting aside: in Montana, miners were the Populists so in Montana it was labor that kept the movement alive and kicking. A similar scenario could be seen in Idaho where the Populist movement will be active into the 20th century.

There were attempts to educate people on the needs and wants of the farmers. For example, the Texas Farmers’ Alliance published a newspaper, National Economist. The Texas Farmers’ Alliance also sent out lecturers to inform the population.

Meanwhile, Kansas merchants feared losing money and power to the Alliances so merchants in Kansas ferociously campaigned against the Alliances arguing the Alliance system was a southern, Confederate activity. In reality, that meant the GOP businesses were pitted against Kansas’ GOP farmers. In 1890, Kansas alliances formed the Alliance Ticket. Leaders of the movement called for a convention. About 6,000 attended and invited the president of the Southern Alliance, L.L Polk. Polk famously said “The farmers have risen up and inaugurated a movement the world has never seen.” He used the word “revolutionary” to describe the political activism of farmers.

Peter Argersinger argued for three general reasons for the rise (and success) of the Alliance Ticket in Kansas:

“The boom in the city had been largely based on unwarranted optimism and an artificial demand, and the first sign of wavering in that confidence revealed the shaky character of the entire development. The prosperity in rural areas had resulted from the inflated prices for agricultural products of the first years of the 1880’s, but by 1885 that foundation had broken down. Adverse weather conditions contributed to the collapse in western Kansas.”

“The price for farm products declined steadily from 1881 to 1885. Corn sold for 83 cents per bushel in 1881 and 28 cents a bushel in 1890; wheat dropped from $1.19 in 1881 to 49 cents per bushel in 1894. The United States Department of Agriculture reported in 1893 that corn and wheat, among other crops, had for the last 10 years had been selling regularly for less that the cost of production. [6] The sharp drop in prices for agricultural products was such that a readjustment of land values was not only proper but a practical necessity. Moreover, the eight-year period of unusually heavy rainfall was followed after 1886 by a period of unusually dry weather.”

“The creation of an overwhelming debt, public and private, was another consequence of the Kansas boom settlement. It was taking an ever increasing amount of the farmer’s products to pay his debts; a mortgage worth 1,000 bushels when contracted now required 2,000 bushels to be retired. Too, with the drop in prices the value of the farm itself fell, and a farm which five years previously was ample security would not now sell for enough to pay the mortgage.”[1]

Nearly all Alliance candidates won their elections in Kansas. The GOP in Kansas was shaken. The Kansas Farmers’ Alliance members demonstrated that a separate political party was the way to go. But in the South, farmers found it hard to separate from the well-entrenched Democratic party. In fact, some simply wanted to try to coop the Democrats. But some Democrats came out against Macune’s subtreasury system in Texas, while most seemed to have supported the subtreasury idea, which helped those who favored the subtreasury system to leave the party of their fathers.

Alliances continued to send out lecturers, who in turn argued, among other things, that the Democratic party would not do the farmers’ bidding. These lecturers had a lot to do with the forming of the People’s Party (internal education). Besides the lecturers, southern Alliances held big conventions, smaller meetings, continued to give speeches to small and large crowds, which eventually resulted in the formation of a third political party at the St. Louis convention, February of 1892.

At the convention, L.L Polk told the delegates that the time had come to link together and take possession of government -a tactical retreat to Jeffersonian republicanism. Also in attendance was Ignatius Donnelly, from Minnesota. He argued the nation was on the verge of moral, political and economic ruin. The old political parties allowed all of that to happen. Pol and Donnelly’s speeches reflected the maturity of the movement. A call for the establishment of a national political party of and for farmers. A third party needed to be formed. So . . .

In Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4th (the date was not coincidental) 1892 the Peoples’ Party adopted general progressive reforms. But first, the Knights of Labor deflated after the Gould strike. Their members did not join the Farmers’ Alliance, but the American Federation of Labor moved to fill the void left by the deceased Knights of Labor. The AFL was more willing to work within the political status quo than by starting a new political culture. Thus, the labor movement was not ready to make the cultural shift that the farmers were willing to make. The AFL will overwhelmingly join the Democrats in the 1930s. Back to the story:

The platform included such progressive reforms as calling for an 8 hour workday, a graduated income tax, the popular election of senators, the secret ballot, and the referendum, to name a few. But the core of the People’s Party platform in 1892 was the big three: transportation, land, and money.

Transportation: public ownership of railroads and public ownership of the communication system. These points are usually pointed to to argue that the People’s Party was just a bunch of socialists).

Land: End to monopolistic ownership (speculation) and an end to alien ownership. This point suggests there existed a bit of xenophobia within the ranks.

Money: called for a subtreasury; the free coinage of silver and gold and to increase the money supply by printing more greenbacks without intrinsic value (not tied to gold).

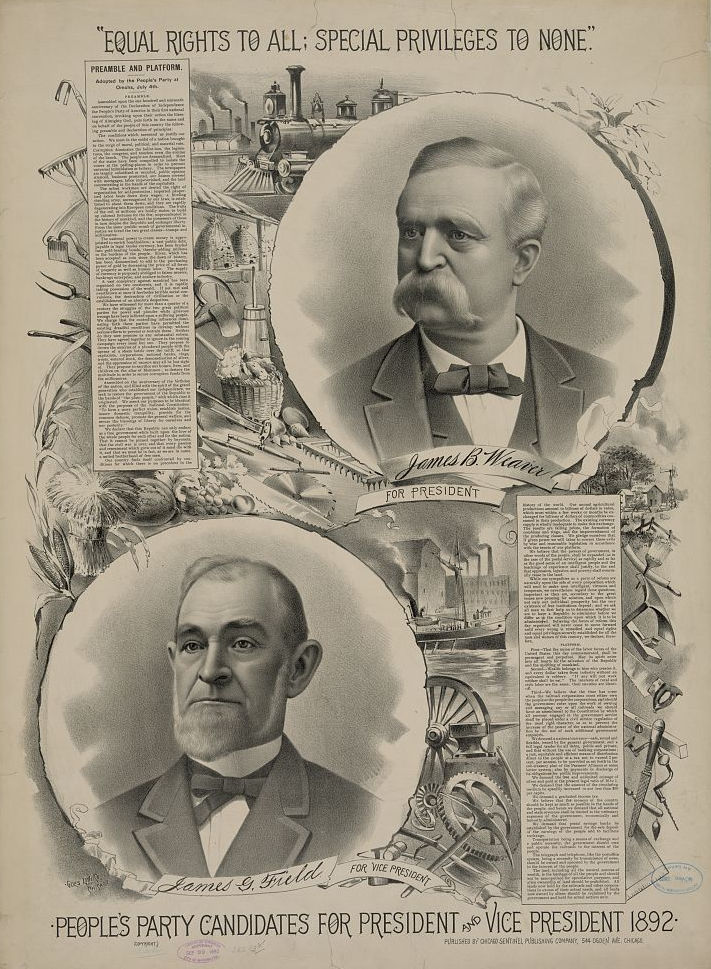

The delegates selected General J.B. Weaver for president (an ex-Union army officer) and General J.G. Field for Vice President (an ex-Confederate army officer). This was clearly an effort to heal the north-south split over earlier issues such as GOP vs. Dems and the question of colored farmers.

Both agreed that women could become members. For example, see this old MA thesis on women in the Texas Farmers’ Alliance,[2], in the Kansas Farmers’ Alliance,[3] and this 1990 article on women in general in the Farmers’ Alliance.[4]

In the 1892 presidential election, the Populists candidates received about 1 million votes but Grover Cleveland (D) won in part due to the People’s Party interjection of the third national candidate, which votes would probably have gone to the Republican candidate. Some in the People’s Party wanted to retreat to the traditional parties and work within, opposed to without, traditional parties.

Four years later marked a major shift in American politics, which some historian, (I cannot remember who, maybe McMath or Goodwyn or Clanton) said “the watershed decade.” American politics were stable through the Gilded Age to about 1890 because the two major parties differed little on the issues. The presidency during the Gilded Age is known as the “Lost Men” who did not weild power like presidents in the 20th century would. Robber Barons allowed to run business without government intervention or interference. With a few exceptions: civil service reform (1883) and regulation of railroad rates (1887). Tariffs remained in place.

1890, a non-presidential election, saw a Democratic landslide in Congress (from 155 seats to 235 seats). Two years later, Cleveland defeated Harrison by the biggest margin since 1872. This meant that voters shifted to the Democrats, temporarily. Due to the panic and depression of the id 1890s, voters will swing back to the GOP. The Republican ascendancy began in the 1894 election and will end with the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as a result of another depression. Woodrow Wilson was a blip on the GOP radar.

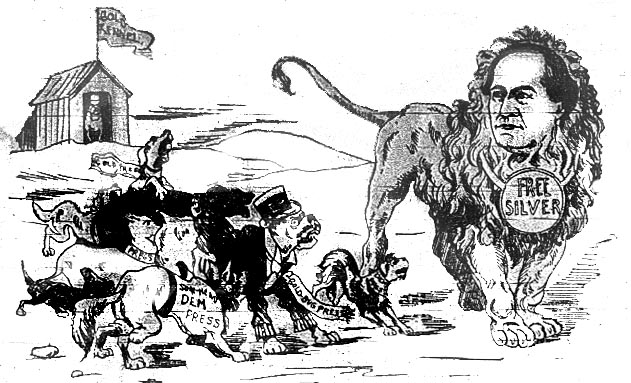

Free Silver became the Populists sole issue in response to the 1893 Panic and the Cleveland administration repealed the Sherman Silver Act. Remember the “Crime of ’73”? The government quit coining silver but the Sherman Silver Act reversed that decision but the Act was repealed in ’93 in reaction to panic because people were redeeming silver for gold, so gold was being depleted -there was a run on gold. Silver miners supported the “American Bimetallic League: for silver coinage, so the silver question loomed for everyone.

Urbanite in the northeast did not support the People’s Party in 1892 so the “fusionists” wanted to join with one of the major parties but the Democrats in the West were silver supporters (miners) and the Democratic leaders suggested that the People’s Party downplay the radical planks to concentrate on the silver issue.

So, Populists afraid of continuing down along that “radical” directions, the silver issue gained traction while the Party leaders seemed to have lost interest in greenbacks. Looks like the People’s Party co-opted the silver supporters in the West. In all, the People’s Party ideas were diluted due to the focus on the silver issue. For example, the leader of the People’s Party in Nebraska was William Jennings Bryan. He supported the silver issue and ignored the rest of the Omaha platform. Fusionists maintain People’s Party integrity (loyal to the Omaha platform) and others did not know what to do. This tends to illustrate how difficult it really is to form a successful third party.

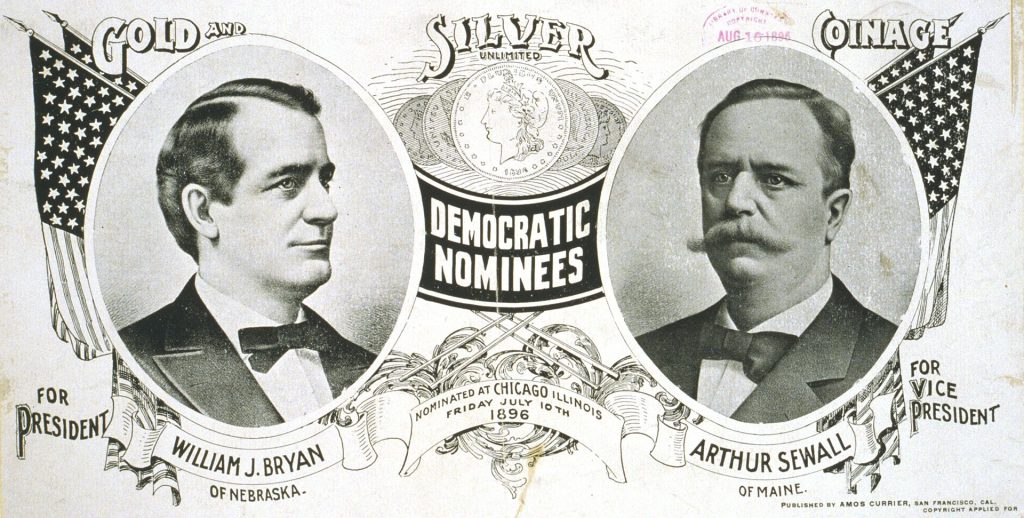

So the election of 1896 seemed to boil down to coinage in gold of bi-metallic. The GOP convention nominated William McKinley, who promised to keep the US on the gold standard. And, he was more interested in tariffs than the money issue. By the way, I think McKinley was the first to use a political manager (Mark Hanna) to run his election. McKinley and the GOP became associated with the gold standard, protective tariffs and middle class values.

The Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan (who was only 36, I believe). Silver was his issue so the two major parties gave electors a choice between two different ideologies, at least when it came to the economy. And Bryan was known for his “Cross of Gold” speech, “a cause as holy as the cause of humanity.” Clear religious tones there, folks. But the Democrat “gold bugs” left the election when Bryan was nominated, put together a caucus and nominated someone else who told Democrats to vote for McKinley. The Democrats also used a political strategist. I believe he was the governor of Illinois -John Altgeld. And just to make things fun, two weeks after the Democrats nominated Bryan, the People’s Party also nominated William Jennings Bryan but they went with a different fellow for vice president, Tom Watson of Georgia.

McKinley had the “front porch” campaign. Older, wiser, conservative. People came to him to talk while Bryan toured the country. He traveled about 18,000 miles and publicly spoke everywhere. Hanna marshaled a huge war chest from corporations (a new kind of campaign) and rich folks. Hanna issued pamphlets, posters, etc., and sent out around 1,400 speakers. One of those speakers was a young man named Teddy Roosevelt ho warned that Bryan would be a huge mistake for the country.

On the surface, the election of 1896 looked like a class race: the discontented versus the powerful but Bryan was leading a party that really was not that different than the Republicans. Bryan supported silver and the Democrat’s supported high tariffs and neither McKinley or Bryan complained about alien-owned land, speculators or supported private railroad ownership. Bryan won the hinterland, such as Washington and McKinley won in the urbanized and industrialized Northeast, Midwest plus Oregon and California. The GOP gains in 1896 solidified their gains in 1894, assured supremacy for further generations but also party structure changed. And the Democrats changed: they became even more racist than the Redeemers, Jim Crow laws increased as too did lynchings. The 1896 election could have been a class contest if the People’s Party stuck to their ideological guns but they did not.

1896 was the high water mark of political discontent but it looks to me that the party system absorbed that discontent rather than being overwhelmed by it as between 1854-1860 when the Republicans were established and took the White House and Congress. The 1896 was the end of Populism, for the most part. Populist candidates continued to win elections in places like the Dakotas, Idaho, and Washington into the 20th century.

So what happened? The People’s Party seemed to have espoused the ideology of spreading the wealth of the Gilded Age (public ownership of railroads, sub-treasury system, etc.). And ultimately the People’s Party could not dent the system because they were absorbed by the two major parties. Maybe the Populists were too ambivalent? Too many interest groups: farmers, Grangers, greenbacks, single-taxers, followers of George Bellamy, Knights of Labor, woman’s suffrage, Prohibitionists, the North, the South, the West. YIKES!

Certainly their internal organization was not strong in most areas. While the People’s Party limped on in the West, Labor was really never brought into the movement back east. Labor tended not to be too keen on the People’s Party monetary system plank. Easterners did not want the increase in farm prices or the injection of more money into the system, which would result in inflation. Overproduction and economic turn downs were devastating for farmers but great for consumers. So, it’s difficult to build a broad coalition and, the Populists turned away from the Omaha Platform in just four years.

Maybe the Populists were out of step with what was going on in the Gilded Age. Changes in the Gilded Age seemed to have confirmed and sanctioned the belief that human rights were not universal and that “progress” meant economic production -the sin quo non of progress is industrialization! Maybe for a brief moment people joined hands and strove to build a cooperative commonwealth, but before they knew it, the People’s Party turned away from it’s Farmers Alliance beginnings.

By the way, the 1896 People’s Party chairman held off on telling Bryan that he was their nominee because he thought Bryan might reject their nomination. Goes to show the Populists’s leaders lost faith in the movement. Farmers’ Alliances dropped in membership and numbers of groups. Smaller coops were set up in Texas but nothing near their initial ideas. Farmers still could not get credit. Coops failed after the 1898 election because big banks would not deal with them. Alliances lost their former cohesiveness. Issues were lost or the farmers lost interest. They were no longer forward-looking but went back to struggling to make their immediate needs met.

And, many Americans saw the People’s Party as irrational and un-American as many Americans embraced capitalism as the only path to take, to succeed in life. The Populists worked outside of the proven political strategies, thus were they destined to fail? The People’s Party was certainly out of step with the writings of William Graham Sumner, a sociologist and professor at Yale. In 1883 he wrote What Social Classes Owe to Each Other. And the answer seemed to be nothing because there was nothing anyone could do to elevate the poor. To act upon the natural order of things was an attack on liberty Here are two excerpts from Sumner’s writings:

Keep this in mind: the baton of the Omaha Platform, which failed to materialize by the 1896 election, will be picked up by the next reformers -the Progressives. By 1900 the Populists’ ideas failed to materialize. But within 30 or so years later, much of their ideas will become so when the Progressives (which includes Teddy Roosevelt and his Democrat cousin Franklin Roosevelt) take the stage.

In the Fall of 2019, some of my students looked into the background of the Populist movement. This is what they came up with:[5]

I. Farmers Alliances[6]

The Gilded Age, named by Mark Twain, an American writer, compared America’s exterior as shiny gold with an interior of brass. The comparison was due to the corruption of industrial capitalism maintained by the wealthy and big businesses. Of those in favor of its industrial elites included oilman John D. Rockefeller, railroad operator Andrew Carnegie, and steel magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt.[7] Union Pacific Railroad owned the tracks and was monopolistic working alongside banks and the industrial elites. Farmers were faced unaffordable high railroad rates to transport their goods, the prices of their products were dropped, and there was a deflation in currency which leads farmers to a downward spiral towards debt.[8] Farmers struggled to make ends causing an agrarian depression that would spread across Texas initiating an alliance of unions and organizations.

The first alliance rose out of Lampasas County in central Texas called the Farmers Alliance, an organization that confronted the economic inequality in 1875 between local farmers and industrial elites. By 1886, this alliance swept across the whole state. In August 1886, the Farmers’ Alliance known also as the Populist Party, held a convention at Cleburne, Texas to demand political action for their economical problems leading to the creation of the Cleburne demands. The location of meeting may have been chosen due to the excellent water source on Buffalo Creek that attracted travelers.[9] Another possible fact to consider is that Cleburne, Texas is located in the South and they were the Southern Alliance. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss cost and revenue from cotton production. Shipping cotton was expensive and patrons and laborers weren’t profiting from the production. Farmers were losing more due to “false weights, defective sampling, cliques, corners, and transportation charges”. Demanded State alliances have secretaries to find the best rates and best markets for commodities. The three main focuses of the demands were regulation of railroad rates, selling of land, and monetary reform. From Cleburne came a bold declaration of agrarian rights. The farmers demanded cooperative economic exchange, government regulation of banking / industry and a flexible national currency. Farmers were outraged, because they believed that political and economic machines controlled them by not negotiating prices for goods and railroad rates. Farmers felt it was time to demand change. Cleburne brought out one of the movements visionaries, Charles Macune. His leadership skills were put to the test when he was put into heated discussions between those with political involvement and business only solutions.[10]

Charles Macune was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a state where Germans immigrated to and brought the idea of pro-union. Macune was a man that held various positions which included pharmacy clerk, house painter, newspaper editor, hotel proprietor, physician, lawyer, minister, medical missionary and farm hand. Macune may have brought the idea of pro collection to Texas Farmers. In 1871, after the Civil War, Macune made Texas his home.[11] In 1885, he joined the Texas Farmers Alliance becoming the leader of the Farmers Alliance an economic movement in the south as elected chair of its executive committee, agrarian and monetary reformer in 1887.[12]

With Macune’s efforts as the leader, the Farmers Alliance was successful with the boycotts they created that helped lower the price for goods and were gaining more support. In December of 1889, leaders of the Farmers Alliance introduced the sub treasury plan, which called for the federal government to give farmers low-interest loans against non perishable crops, which were to be stored in government-built warehouses. Introduced in both houses of Congress in February 1890, the bill quickly became buried in committee, never to be enacted.[13] The Farmers Alliance started making progress and trying to get people from the Democratic candidates to support the Alliance and to secure votes.

The Farmers Alliance also started cooperating with the Democrats and made sure that Democrats were elected to crucial issues as taxation, the crop lien system, and the regulation of railroads and out-of-state corporations convinced many Alliance members that the Democratic Party would never support the Alliance reform program.[14] Due to losing support from the Democrats, Alliance leaders would create the Populist Party in 1892. Their purpose was to do the same politicize of the Farmers Alliance and promoting the idea that their sole purpose was to help common people alike. The decline of cooperative enterprises and the internal strife engendered the support of the Populist Party led to the rapid demise of the Farmers Alliance.[15]

The Farmers alliance continued to help support candidates in hopes to get elected and to keep the Populist Party going. In the 1896 presidential election, the Democratic Party nominated William Jennings Bryan and adopted a platform that included several planks from the 1892 Populist platform. After much discussion, Populist leaders decided to support Bryan and in so doing, signed the death warrant of the Populist Party.[16]

II. Three Problems Facing Farmers[17]

“During the Gilded Age, the United States had experienced rapid economic growth with industrialization benefitting big industries such as railroads, coal mining, and factories. However, farmers had encountered a few economic problems that would place them in debt and cause them to lose their land. These problems include the overproduction of crops, tariffs, sharecropping, and railroad companies.

The first problem that farmers in the west faced was the overproduction of goods. Farmers wanted to pay off their debt from railroad shipping rates and supplies purchased, so they gradually produced more crops every year.[18] However, the abundance of crops decreased the crop demand and thus lowered the prices of goods. For instance, cotton production had doubled while its price decreased from roughly 15 to 6 cents per pound (from 1873 to 1894).[19] Mary Elizabeth Lease, a Populist orator who helped began the revolt of Kansas farmers against railroad rates and high mortgage interest, questioned the overproduction problem and advised farmers to “raise less corn and more hell.”[20] Industrialization and the westward expansion of homestead settlers also played a role in the overproduction of goods. Better farming tools (plow) and machinery (reaper-binder) made it more efficient to grow crops, and the Homestead Act encouraged settlers to move West and work on their farms to gain ownership of the land promised to them.[21]

Farmers also fell victim to U.S. tariff policies such as the McKinley Tariff that dealt with imports during the Gilded Age. Farmers were forced to buy items that were manufactured for survival, while selling what they produce in a wide competitive market at low prices mostly because of foreign competition. By implementing an import tax or duty on manufactured goods, the government hoped to make them more expensive than the similar American manufactured goods. Some industrial manufacturers argued that protective tariffs were temporarily necessary to encourage investment in industrial concerns by making them less risky and claimed that small industries needed this form of protection from foreign competitors like the Europeans. One opponent of the McKinley Tariff was Congressman McClammy from North Carolina, who argued that the tariff was unfair and proposed amendments to the internal revenue clause of the tariff bill.[22]

Sharecropping also became a prominent fixture in the southern agricultural economy. In sharecropping, African Americans had no choice but to rent land and give a small portion of their crops yielded to landowners. For example, in a contract between Isham G. Bailey and freedmen Cooper Hughs and Charles Robert, Bailey had much control over the crop yield and the freedmen’s family. Both freedmen were to raise and give more than half of their cotton and two-thirds of corn to Bailey, and the contract also gave specific requirements to the freedmen’s kids and wife.[23] In addition, lawmakers took the side of landowners and implemented clauses such as “black codes” to make it illegal for those in debt to flee their farms or sell to anyone that isn’t their landowner. The Reconstruction period was supposed to be a time for freedmen to excel, but sharecropping made them have no autonomy in how and when they produce crops.

Lastly, farmers experienced problems with railroad companies (such as the Union Pacific Railroad). Farmers relied on trains to ship their products, but railroad companies did not offer a discount or rebate. Railroad companies were more concerned with losing the shipping of industrial products instead of agricultural products because of overproduction. Therefore, the railroads were more likely to make deals with big businesses instead of farmers. Because of the lack of support from railroad companies, this eventually led to the creation of the first farmer group, the Grange, in 1867. With the help of Oliver Hudson Kelly, the Grange will influence changes for farmers by creating cooperatives that could help them obtain better shipping rates and prices on material to farm.[24] For example, when farmers in Illinois convinced their state legislature to pass a bill that would fix maximum rates that railroads and grain-storage facility could charge, a grain-storage facility in Chicago challenged the constitutionality of the maximum rate. As a result, the Supreme Court case Munn v. Illinois (1877) upheld the principle of state regulation, declaring that grain warehouses owned by railroads acted in the public interest and therefore must submit to regulation for the common good.[25]

III. The Election of 1892[26]

The People’s Party arose during the Gilded Age and was founded in 1891. Groups of farmers alliances joined the populist movement said to be “For the People.” The People’s Party was also known as the Populist Party that was created towards the end of the nineteenth century.[27] The founders of the Populist party were James B. Weaver and Leonidas L. Polk.[28] A national election was never won by a third party and Populist Party’s no exception. Their goal was to adopt a platform for a free coinage of silver, graduated income tax, abolition of national banks, elections of senators, government ownership in communication and transportation. In that convention, farmers and labor workers created Omaha Platform. They chose Omaha as a Platform because their first goal was to increase the coinage of silver into gold. During this area, we also began to hear the voice of very outspoken women such as that of Mary Elizabeth Lease, who after failed farming ventures joined the movement in Kansas of farmers who were tired of high railroad rates and a greedy government.[29] In a speech given by Lease in 1891 to the National Council of Women, she states “The farmers, slow to think and slow to act are today thinking for themselves […] They have been awakened by the load of oppressive taxation, unjust tariffs, and find themselves standing to-day at the very brink of their own despair.”[30] This speech may have been one of the best examples showing the sentiment of not only lease but of all farmers at the time. Like Lease said in her speech farmers were becoming fed up with the situation they had been put in, with many farmers being in debt which was only made worse by high interest loans and now they were finally acting. Her speeches quickly picked up steam and the Populist Party became aware of her unapologetic way of speaking which eventually made her a key orator for the Populist. Although often overshadowed by Leases outspokenness, Annie Le Porte Diggs was a woman who also became massively involved with the emergence of the populist party. Diggs involvement with the populist began in Kansas alongside the Kansas Populist party that had formed in June of 1890. That year, she spent speaking across the country about farmers’ grievances, noting that farmers, and the eastern working class shared the same hardships. She continued advocating for the populist movement until 1892, where she officially became a delegate during Omaha’s convention for the People’s Party. As it’s known, the Populist party was officially launched as a third-party after said convention and Diggs job continued. That fall, Diggs campaigned alongside Mary E. Lease and James B. Weaver throughout the west in efforts to gain the support of those who could benefit from the party’s platform.[31]

Leonidas Lafayette Polk was one of the US state activists who advocated for farmers and their rights. He founded the magazine the Progressive Farmer to improve the rural farm household and develop strong sides of the American democracy.[32] One of his prominent achievements was joining The Populist Party. The preamble was written by Minnesota lawyer, farmer, politician, and novelist Ignatius Donnelly. He was a person who wrote a lot of articles about the People’s Party. In this case, he asserted that the government did not allow the community to speak out; therefore, the writing was one of the possible ways to find out the truth. As a result, Ignatius Loyola Donnelly decided to talk about corruption, election, and the unlimited issue of silver and gold coins. Donnelly was able to inspire many with the revolutionary words such as the “tramps and millionaires” argument in his preamble:

The urban workmen are denied the right to organize for self-protection, imported pauperized labor beats down their wages, a hireling standing army, unrecognized by our laws, is established to shoot them down, and they are rapidly degenerating into European conditions. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of those, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty. From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice, we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires.[33]

His preamble would also resonate with the people in Omaha.

The Omaha platform was the party program adopted at the formative convention of the people’s party held in Omaha, Nebraska on July 4, 1892. Farmers all over the country met in Omaha Nebraska because it is the geographic center of the United States. It was so the basic tenets of the populist movement could be set out.[34] A program that advocated for the limitations of corporations and business’s sexual practices. It created the free and unlimited coinage of silver to create inflation and bring more money to the table. Bimetallism was a major factor and considered the” Crime of 1873” due to the ratio of 16 silver coins was equal to 1 gold coin. The movement got rid of the national banking system. Also, the printing of more cash was available, that way people could borrow cash more easily. There was national ownership of all public communication and transportation. Which helped by dividing each work and income. The income tax started becoming more progressive, meaning the more money you make the higher percentage of your income was tax. There was more direct democracy on specific acts of legislation, and it started being illegal for foreigners to own land in the United States.[35]

The party designated James Weaver as its 1892 presidential candidate. In the 1892 Presidential election, the Populist ticket of James B. Weaver and James G. Field won 8.5 percent of the national popular vote and carried four Western states, becoming the first third party since the end of the American Civil War to win electoral votes. The song “Good-by, Party Bosses” obtained 1,029,846 popular votes for General Weaver.[36] This event helped with votes but wasn’t enough to win the election. Even though they lost the 1892 election, all the ideas were later implemented. Farmers fought for decades of economic problems to be solved during the election. Weaver based his campaign agendas on legislation to reinforce American farmers’ authority in business, diminish monopolies’ influence in the U.S. economy, and introduce changes that would reduce the power held by railroad corporations, banks, and government agencies.

In conclusion, Cleveland defeats Weaver to regain presidency. The Populist movement may have been too early for its time. By the election of 1896, the Democratic Party had absorbed many of the Populist ideals, causing the People’s Party to cease to exist as a national organization.[37]

IV. Not just farmers. The plight of the “working man” was taken up by Samuel Gompers. Jada Ballard looked at Gompers in the Fall of 2019 when she was one of my US History students:

Samuel Gompers became the American Federation of Labor’s first president at the age of twenty- seven.[38] The formation of this union was made up of mostly skilled workers, like Samuel who was a cigarmaker. Gompers didn’t include those that were considered unskilled in the union, because Gompers felt that those who were skilled held more economic power. The division caused the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to represent unskilled workings during the Great Depression. The American Federation of Labor is important to history, because it pushed forward the framework of former union “Knights of Labor.” Knights of Labor which failed because of the Haymarket Square, a labor protest rally near Chicago that turned deadly. The AFL did approve of labor strikes only when it became a necessity, for example Gompers speech at the Cooper Union meeting.[39] During this meeting he declared, “there comes a time when not to strike is but to rivet the chains of slavery upon our wrists.”[40]

Gompers leadership with the AFL changed how labor unions were being led during the populism era. He wanted the AFL to work within the framework of American capitalism, which helped forward the mission of the union. The AFL impact on union would go on to influence 23,000 labor strikes and became the national organization of labor.[41] The AFL also influenced Congress to pass Labor Day in 1881 and the Clayton Act 1914. Labor Day was created to acknowledge the social and economic achievements of American workers. Labor Day is important to history because of leaders like Gompers, who used peaceful protest to create change. Samuel Gompers called the Clayton Act, the Magna Carta of Labor, because it would legally lift the unfair human labor suffered by workers. Gompers would also go on to have 6,610,000 labor workers in the AFL, the most by any other labor union.[42] The significance of this achievement was that it caused a loss of 450 million dollars to the industries that inflicted unfair situations for their workers.

In conclusion, Gompers leadership and determination for working within American Capitalism, was the reason the AFL lasted so long, even after the CIO merged in 1955.[43] Gompers was able to help labor workers either meet halfway or fully receive better benefits. This is important to history because it became a positive outcome in unfair wages for labor workers. Unlike other labor unions they didn’t have the impact of success, because Gompers presented things that were realistic and larger than the others. After examining his impact on labor unions, it influenced the creation of the Clayton Act and Labor Day. The important of Gompers achievements shared how others would lead movements for the better.

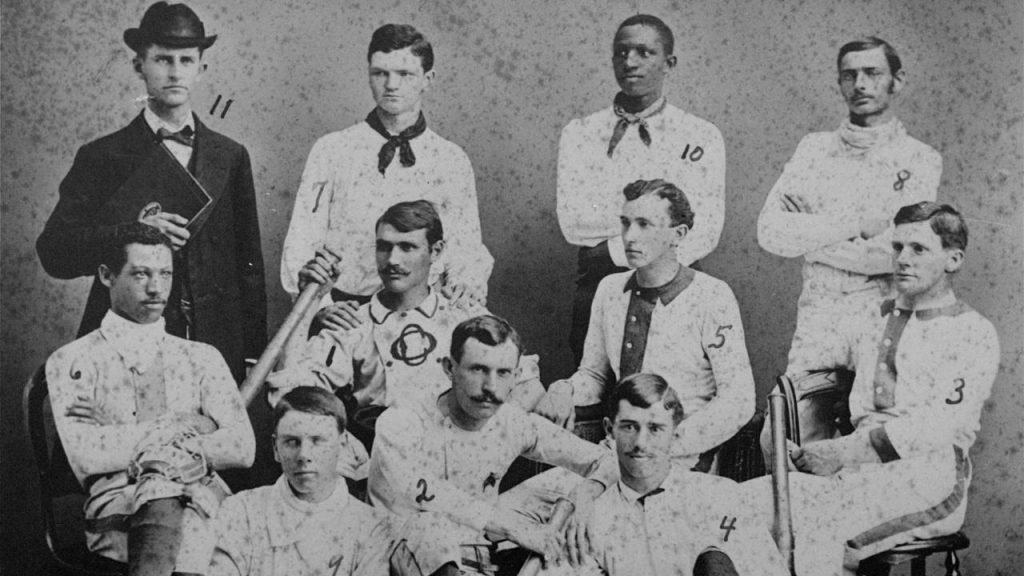

Finally, something that had nothing to do with the People’s Party, but happened around the same time, was baseball. Baseball’s popularity increased in the decades following the Civil War. Teams were spread across the country from New York to the territory of Arizona. Eventually, major league baseball will ban African American players but until that time there will be many African Americans who played professional baseball to include Moses Fleetwood Walker. This is an essay on Moses Fleetwood Walker by Cynthia Romero:

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born on October 7th, 1857 in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. He was the first African American man to play in the Major League Baseball (MLB). He made his debut in May 1884, playing as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association. At that time, there was still a lot of anger and hate towards black people. As mentioned by Nudie Williams, “Slavery was still, however, a part of society that served to define blacks, slave and free, in a very negative way.” [44]. As expected, by playing baseball during that era, he immediately exposed himself to many people who exhibit racial bigotry. However, he managed to continue pursuing his dream of becoming a professional player and ignore the expressions of hatred against him.

Moreover, the color line was a visible problem in American society, which kept it divided for many years. White supremacy led the country in the 19th century; blacks were considered an inferior race, and many would have little opportunities to rise above from that position. Even this newly game at the time, such as baseball, reflected the prominent difference between races. The acceptance of Fleetwood in a Major league team did not change many things. In a 1919 interview and many years after retiring from baseball, Tony Mullane, Walker’s teammate in the Blue Stockings and one of the most outstanding pitchers of the 19th century, referred to Walker as “the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals”.[45]

Fleetwood had to face several challenges during his time as a major league player. He suffered insults from opponents and fan abuse because of his skin color. According to Williams:

Besides hisses and boos, there were real threats to his physical well being in the other southern city—Richmond. The manager of his team, Charles Morton, received the following letter in the mail: We the undersigned to hereby warn you not to put up Walker, the negro catcher, the evenings that you play in Richmond, as we could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes on the grounds in a suit. We hope you will listen to our words of warning, so that there will be no trouble; but if you do not there certainly will be.[46]

Another incident that resulted of him being discriminated was when his team had an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings and the manager of this team, Adrian “Cap” Anson, refused to play if Moses took part of the game. Anson was considered a leader of the white supremacy community in baseball. Eventually, he and his followers pulled out black players from the Majors and excluded them from playing organized baseball not because of their lack of ability but because of their color. This action reflected the national attitude against black people.

After Fleetwood Walker was released from a major league baseball team, there was no more presence of black players in the big leagues until 1947 when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, becoming the first African American man to play baseball in modern era. Goldstein took an extract from Zang’s book “Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer” (1995), ”Walker and Robinson had some common experiences, but while Robinson played at a time when the historical tide was carrying society toward integration, Walker stood as a nearly solitary figure attempting to play ball as an ebb tide swept away popular support for racial equality”. Unfortunately for Fleetwood, his presence was only noticeable for teammates, opponents and fans for his race and not for his performance during the games.[47]

In accordance with Williams, “The same racism that he experienced in baseball carried over into his business ventures and despite his education and middle class background; color would place limitations on his personal ambitions and achievements much as it had done in baseball, the sport, so would it be in America as a society.”[48] The author’s background as an historian with a great passion for African American culture, doing researches for so many years, earning a degree in History, and being a black person himself, helped him to get enough knowledge on this matter and to get to know better what Fleetwood went through in his journey as a baseball player. Williams collected enough data and records to write about Moses’ life.

Fleetwood published a book in 1908 called “Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present and Future of the Negro Race in America” in which he mentions some of the difficulties that black people had to go through back then. In the book, he mentions that “the American Negro realizes on every hand or is made to feel that he is regarded, and must act as a subordinate people”. With his words, he seemed to have given up faith in American society (predominantly white). He also pointed out in his book that white people felt superior than any other person of darker skin color; regardless the person’s education. Moses Fleetwood Walker died of pneumonia on May 11th, 1924 in Cleveland, Ohio. Nonetheless, his legacy is still alive. He made history as the first African American person to ever play in the Majors and wrote about his experiences being a public figure in a racist society and how he fought for black people’s civil rights.

I’d like to thank Cynthia Romero (Spring 2018) and my fall 2019 students Jada Ballard, Samuel Brown, Daniel Diaz, Vanessa Garza, Andrea Gonzalez, Glenda Gonzalez, Frank Granados, Ashley Nandlal, Kim Nguyen, Adam Obregon, Kimberly Peralez,, Nidia Perez, Guadalupe Rangel, Arantxa Perez, Erika Portillo, Esmeralda Rodriguez, Gonzalo Salas, Raul Sanchez, Lam Thuy Van Tran, and Flower Torres for their hard work on the plight of farmers in the late 19th century. Cynthia Romero’s look at Gilded Age baseball is also appreciated.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies, therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-quarterly-road-to-a-republican-waterloo/17453 ↵

- https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/2346/59366/31295003551628.pdf?sequence=1 ↵

- https://www.kshs.org/publicat/history/1984winter_brady.pdf ↵

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED328501.pdf ↵

- The student-authors are Samuel Brown, Daniel Diaz, Vanessa Garza, Andrea Gonzalez, Glenda Gonzalez, Frank Granados, Ashley Nandlal, Kim Nguyen, Adam Obregon, Kimberly Peralez, Nidia Perez, Guadalupe Rangel, Arantxa Perez, Erika Portillo, Esmeralda Rodriguez, Gonzalo Salas, Raul Sanchez, Lam Thuy Van Tran, and Flower Torres. Fall 2019. ↵

- By Samuel Brown, Daniel Diaz, Vanessa Garza, Andrea Gonzalez, Glenda Gonzalez, and Frank Granados ↵

- US History Since 1877 (YAWP Edition), The Populist Movement, HCC Canvas, “para” 2 ↵

- Finley, Randy. 2000. “Macune, Charles William”. In American National Biography Online. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, “para” 2 ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, Richard Elam and Mildred Padon, "CLEBURNE, TX," accessed October 18, 2019, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hec02. ↵

- “The Rise & Fall of Southern Populism / Part I: 1886-1889: The InHeritage Almanack,” The Almanack, accessed October 3, 2019, https://www.inheritage.org/almanack/populist-movement-in-the-south-agrarian-revolt-01/. ↵

- Macune, Charles W. "The Wellsprings of a Populist: Dr. C. W. Macune before 1886." The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 90, no. 2 (1986): 140 ↵

- Finley, “para” 2 ↵

- “Farmers' Alliance.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, Matthew Hild, 8 Apr. 2005,“para 5” ↵

- Hild “para” 7” ↵

- Hild “para” 8” ↵

- McCarty, “para” 9 ↵

- By Ashley Nandlal, Kim Nguyen, Adam Obregon, Kimberly Peralez,, Nidia Perez, and Guadalupe Rangel. ↵

- “US History II (OS Collection),” Lumen, accessed October 1, 2019, ↵

- “Agricultural Problems and Gilded Age Politics,” Accessed October 1, 2019, https://www.austincc.edu/lpatrick/his1302/agrarian.html. ↵

- “Mary Elizabeth Lease,” Kansas Historical Society, Accessed October 16, 2019, https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/mary-elizabeth-lease/12128. ↵

- “US History II” ↵

- “Debate over McKinley Tariff,” History Engine: Tools for Collaborative Education and Research | Episodes, Accessed October 16, 2019, https://historyengine.richmond.edu/episodes/view/476. ↵

- “Sharecropper contract, 1867,” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, Accessed October 18, 2019, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/spotlight-primary-source/sharecropper-contract-1867. ↵

- “20.3 Farmers Revolt in the Populist Era”, OpenStax CNX, Aug 19, 2019, Accessed October 7, 2019, http://cnx.org/contents/1c674e5b-7cd2-4b6d-bf4c-34d72cdc5cc2@8. ↵

- “Munn v. Illinois, Oyez, Accessed October 18, 2019, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/94us113. ↵

- By Arantxa Perez, Erika Portillo, Esmeralda Rodriguez, Gonzalo Salas, Raul Sanchez, Lam Thuy Van Tran, Flower Torres ↵

- History Matters, "Peoples Party". The internet. 5 October 2019. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5361 ↵

- Library of Congress, " People party candidates for president and Vice President 1892". 29 Sep. The internet. 5 October 2019.https://www.loc.gov/resource/pga.01400/ ↵

- Kansas Historical Society. “Mary Elizabeth Lease.” Kansapedia. Accessed October 2019. https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/mary-elizabeth-lease/12128 ↵

- Avery, Rachel Foster. Transactions of The National Council of Women of The United States. Washington, D.C: Executive Board of The National Council of Women, 1891. ↵

- Pierce, Michael. “Annie Diggs, suffragist.” American National Biography Online. Accessed October 2019. https://lists.h-net.org/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=h-shgape&month=0103&week=d&msg=cZkQv8CM9ki1MvrYVwZR8Q&user=&pw= ↵

- Leonidas Polk. Accessed October 20, 2019. https://kansaspress.ku.edu/subjects/history-civil-war/978-0-7006-2750-9.html. ↵

- “Donnelly, Ignatius (1831–1901).” MNopedia. Accessed October 19, 2019. https://www.mnopedia.org/person/donnelly-ignatius-1831-1901 ↵

- historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5361 ↵

- https://worldhistory.us/american-history/populism-and-the-omaha-platform-of-1892.php ↵

- “Part Four Forging an Industrial Society.” Accessed September 25, 2019. http://www.worthschools.net/userfiles/167/Classes/920/chapter23.pdf?id=19591. ↵

- “Gilded Age.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, October 18, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilded_Age. ↵

- “American Federation of Labor.” Ushistory.org, U.S. History Online Textbook, www.ushistory.org/us/37d.asp. (last date accessed, October 16, 2019) ↵

- Abs, McGaughy (ED). American Perspectives Readings in American History, Vol II, 6th ed. New York: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2015 ↵

- Ibid, 204, 400 ↵

- Kennedy, David M., Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey. The American Pageant: A History of the Republic. 12th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001. ↵

- Ibid, 555 ↵

- “American Federation of Labor.” Ushistory.org, U.S. History Online Textbook, www.ushistory.org/us/37d.asp. (last date accessed, October 16, 2019) ↵

- Williams, Nudie E. “Footnote to Trivia: Moses Fleetwood Walker and the All-American Dream.” Journal of American Culture (01911813), vol. 11, Summer 1988, pp. 65–72. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofm&AN=509414815&site=eds-live. Accessed 5 Dec. 2019. p. 65 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Goldstein, Richard. “Moses Fleetwood Walker.” The New York Times, 2019, p. 11. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.572357888&site=eds-live. Accessed 5 Dec. 2019. ↵

- Williams, Nudie E. “Footnote to Trivia: Moses Fleetwood Walker and the All-American Dream.” Journal of American Culture (01911813), vol. 11, Summer 1988, pg. 70. ↵