24 Addressing the Success and Excess of the Gilded Age: The Progressive Era (1880s-1920)

Domestic Reform - Political Reform - Limits of Reform

Jim Ross-Nazzal and Students

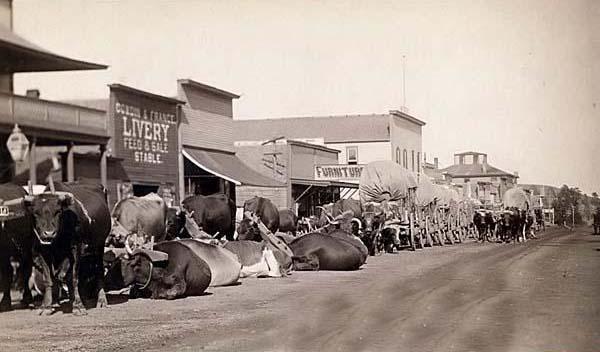

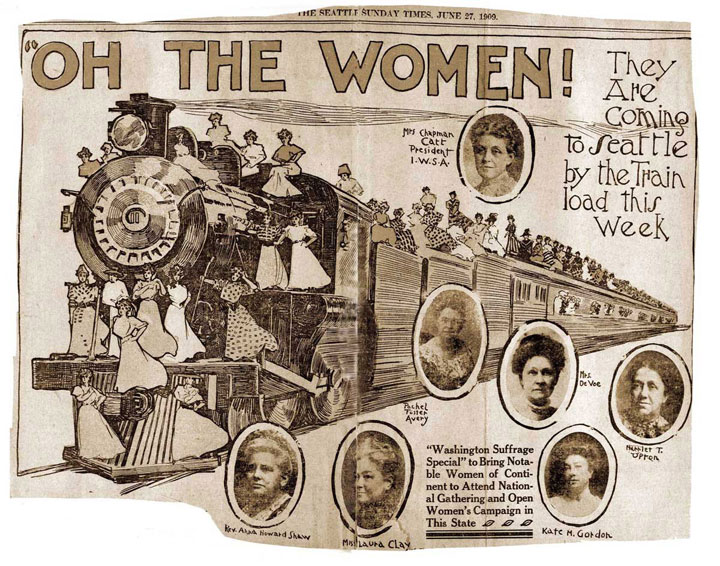

Two Civil War veterans, one soldier and one volunteer, John and Emma Smith DeVoe, arrived to the Dakota Territory like many Civil War veterans in search of the prosperity promised by the railroads and gold being brought out of places like the Black Hills area of what is today South Daokta. They settled in Huron, a young town full of issues as they saw them, such as prostitution, gambling and unpaved streets filled with animal and human waste. Already with a history of reform in both for the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and their church affiliation (Baptist), the DeVoes took to work to “clean up” their new town first by creating voluntary groups -something that was fashionable for that time. Volunteerism was essential in a place and a time when government was limited or non-existent. The DeVoes tended to focus on moral reform, such as closing the saloons and brothels, something that was prevalent during the Gilded Age. But their story also demonstrates a shift to what we call today the Progressive era because very soon the DeVoes will turn their attention to regional then national issues as Emma Smith DeVoe will become a major player in the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association, her work as an organizer was one of the reasons why western states adopted universal suffrage, and after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Emma Smith DeVoe will establish a national organization that transcended political affiliation where women could discuss issues and work for change. Today that organization is called the League of Women Voters.[1]

No time period in American history is possibly as misunderstood, convoluted, and nebulous, yet important to clearly understand to better appreciate the economic, political, and social liberties of American society in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. They are cause and effect. They compliment each other. They overlap. Neither a national movement, nor a singular ideology, or a coherent time frame, the Progressive Era usually falls under the umbrellic Gilded Age at its earliest roots by the rise of agrarian reform measures in the 1870s and, at its demise, the end of the Woodrow Wilson administration shortly after “the war to make the world safe for democracy.” Yet the Progressive seeds will bloom in the 1930s-1940s and again in the 1960s under the presidencies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Lyndon Baines Johnson.

As with other “modern” periods, ages, or times, the Progressive Era traces its roots back to the rough and tumble alleys of thoroughfares of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York where, before the Civil War, burgeoning American factories and ever-increasing immigration created an entrenched working class and a major gang problem (especially in New York). In the first half of the nineteenth century, morally-charged, upper class women silently protested in front of saloons or created urban political parties with the hopes of codifying what they considered anti-social behaviors (not unlike the efforts of the DeVoes in the 1880s). They demanded changes to public and private morality that tended to smack more of social control and less of progressive assistance to the newly arrived immigrants. Nonetheless, what makes the Progressive Era different from previous periods of U.S. history where moral reformers demanded changes to public behavior, was the inherent belief in the use of evangelism, education, and native-born American political, economic, and social ideals to both identify problems as well as to divine solutions. In a word, while earlier reformers used the rod of morality to control behavior, Progressive reformers used academia and their belief in the inherent superiority of American strategies as the fulcrum from which all meaningful change will turn.

Progressive reformers also tended to see the United States on an evolutionary path. Charles Darwin’s ideas on biological change over time began to be applied to society. Known as Social Darwinism, learned Americans tried to figure out why some people failed in life while others succeeded. Why were some poor while others rich? Why were some sickly while others healthy? What caused sin, vice, and malfeasance? The answer was evolution: some groups of people were more evolved than others. The highest stage of evolution on a nation scale was the United States: American religious ideas, American economic theory, American political theory, and American culture were all evolved beyond those of European, African, Asian, and Latin American politics, cultures, religions, and societies.

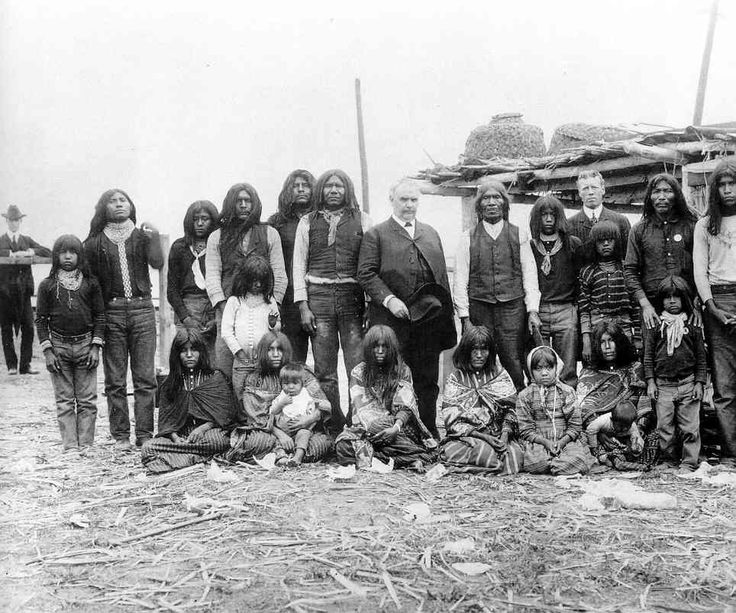

In the late nineteenth century, some Americans will conclude that Americans had a special, God-given mission to spread American social, political, economic, and religious ideas to those who were not as advanced, even in the face of physical hardship. This became known as the “White Man’s Burden,” from a poem written by an English proponent of the duty of civilized peoples to help those who are less civilized.

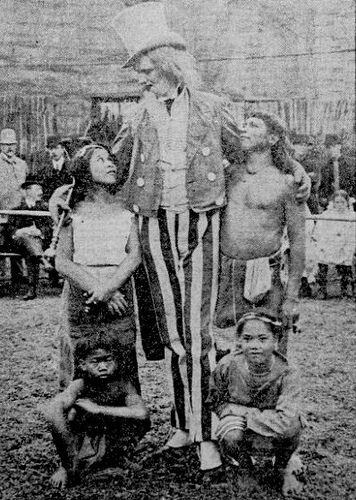

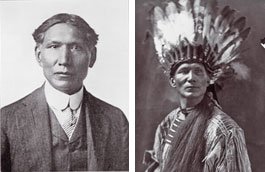

An example of American display in this belief that nations evolve was evidenced in a major theme of the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis: classification. William McGee, one of the directors of the fair, created an exhibit that was a literal walk through national evolution. Beginning with the most uncivilized society, as McGee defined “civilization,” and ending at the most advanced of societies (spoiler alert – the U.S.), McGee strove “to represent human progress from the dark prime to the highest enlightenment, from savagery to civic organization, from egoism to altruism.”

The tour began with a walk through the Igorot Village. The Igorots were scantly clad peoples living in the Philippines who were head hunters and ate dogs. Fair directors supplied dogs to the people, although there were rumors that the Igorot snuck off the fair grounds and procured dogs from the near-by neighborhoods. Then came European civilization but the most highly advanced, evolved, and perfected society was the United States, which was the last stop of the exhibit. The exhibit also included a few freshly painted, steel battleships that were moored in an artificial lake created specifically to demonstrate the new American naval power initially proposed by Teddy Roosevelt when he worked in the Department of the Navy. The Igorot, American Indians, Africans, and other peoples were hired to live, work, and be on display throughout the fair’s run. This exhibit was a physical example of the “truth” that societies evolve—maybe not progressive as we use the word today but certainly progressive for the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Americans.

What did it mean to be a “Progressive”?

The Progressives shared some common traits. First, they tended to have Evangelical backgrounds or experiences. Following the Civil War there developed a swell among Protestants that they were the true leaders of this country (politically, socially, and economically) and thus only they could speak in the best interests of this country, as they professed those best interests to be. This idea led to action, specifically young men (and sometimes women) being sent out around the country and around the world to spread American ideas on politics, society, and the economy through what they believed to be the driving force behind the success of the United States, which of course was Protestantism. Unlike pre-Civil War forms of evangelism that focused on traditional religious preaching (Mark 16:15 “Go ye into all into the world, and preach the gospel to every creature”), Progressive Era evangelism included political, social, and economic evangelism.

Many Progressive reforms had backgrounds in religious evangelicalism, like the DeVoes whose reform impulses began in and with their Baptist church. Today, many American religious groups send out their own to profess their particular versions of “Truth” with the hopes of converting others to their belief system. Mormons might spend two years evangelizing, so too do Jehovah Witnesses knock of their neighbors’ doors. Some evangelize through the media, such as Rick Warren and his wildly popular book The Purpose Driven Life. Possibly this nation’s most-known evangelical preacher of the 20th century was Billy Graham who used radio then television to grow his followers.

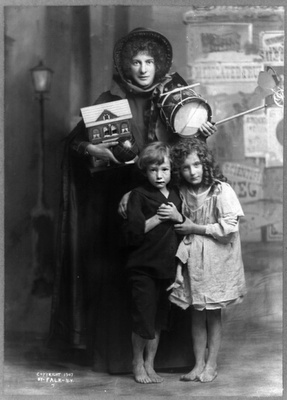

Domestic and foreign missionaries published magazines, such as The Heathen: Women’s Friend; they established offices throughout the American West, Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and Latin America. And, even claimed the United States on behalf of God such as William Booth (founder of the Salvation Army) when in the early spring of 1880 Booth established a missionary outpost in New York where his followers began preaching to the homeless of the largest city in this country. Evangeline Booth, a daughter of the founder, became an American citizen and led the Salvation Army in the United States for three decades (1904-1934). The Salvation Army had the twin tenets of religious salvation through Jesus Christ with a combination of Methodism and a whiff of millennialism and social salvation in which the group tried to rid the world of poverty. It is the second of these goals that this English organization will affect American Progressive reformers and ideas, such as Jane Addams and the Settlement House Movement (see below).

Interestingly enough, the rise of evangelism paralleled the dramatic increase in the number of Roman Catholics in this country. In the last three decades of the nineteenth century, Roman Catholics doubled in numbers causing more than mere concern among the native-born Protestants. Some of this nation’s most popular evangelicals included Dwight Moody who preached an exceptionally pessimistic view of human history and Washington Gladden who, out of step with most Americans in the late nineteenth century, called for the federal government to take an increasingly active role in protecting unions and the working class.

A second trait common among those who hoisted the Progressive banner was a grounding in social sciences. Before the Civil War, academic pursuits were exceptionally limited in both the numbers of Americans who could afford to attend colleges as well as the curriculum offered at those institutions. Many universities offered students what they considered to be a well-rounded education grounded in the classics such as Latin, Ancient history, and Renaissance art. After the Civil War, more universities began allowing women to attend and so too did their curricula change to include classes in “new” disciplines such as anthropology, political science, sociology, psychology. The need for people with educational backgrounds in engineering became evident as this nation’s railroad system spread further west and connected more communities than ever before. As more family-owned, mom-and-pop shops or general stores became gobbled up by national corporations such as the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco), International Business Machines (IBM), or Standard Oil, industrial leaders such as John Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Andrew Carnegie increasingly demanded employees who had educational backgrounds in business, as opposed to Medieval art, for example.

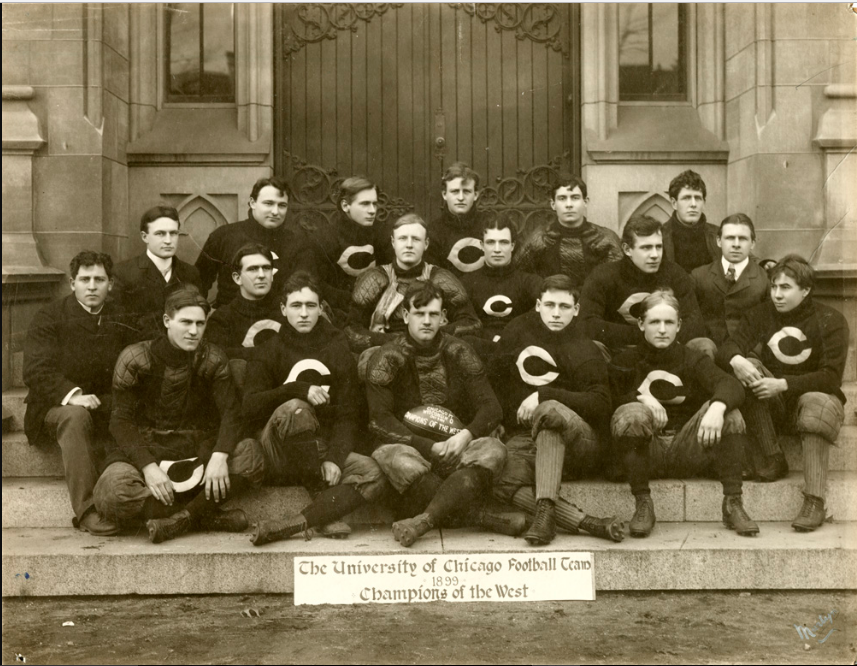

With the sheer lack of anything resembling a business program, Rockefeller used his own money to create an institution tasked with training business leaders. His school, the University of Chicago, also created a new, advanced program for the study of business called the Masters in Business Administration, or MBA. Before the Civil War, the only school that offered degrees in engineering was the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

These new fields of study had one thing in common: they all examined human behavior (sociology) or overcoming obstacles (such as in engineering). The study of human behavior usually focuses on the negative or abhorrent thus once you study the rules to how societies are ordered, you begin to identify problems and then you get to apply your knowledge gained in university study on how to solve those problems. The spread of both engineering schools, as well as institutions that offered programs in business, resulted in the idea that the world (or at least the United States) could be categorized, evaluated, assessed, and proper measures applied to fix problems or to surmount obstacles.

In other words, the development of social sciences and engineering programs and their application to society was strikingly similar to the Enlightenment, which hit the British colonies in North America during the first half of the eighteenth century just before the American War for Independence. And not unlike the Enlightenment that produced physical spaces to showcase “modern” ideas and inventions (such as universities, libraries, and even fairs), Progressive era accomplishments too were celebrated in public spaces.

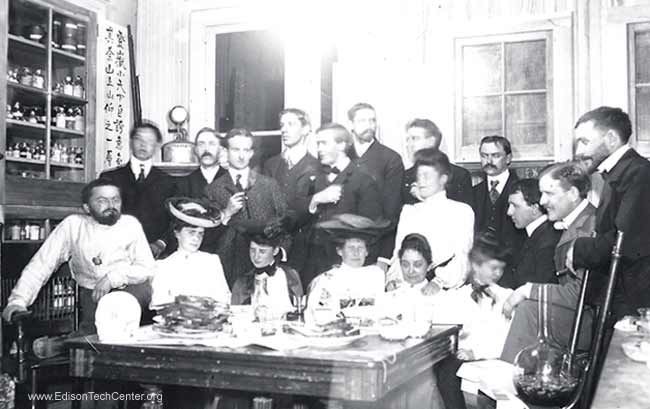

Colossal, year-long extravaganzas to publicize and draw attention to accomplishments, shine light on new ideas, and demonstrate American technological advances was evidenced in the world fairs that were iconic glimpses of everything new, bright, right, and wrong in the Progressive era. At the Chicago fair in 1893, which drew an estimated crowd of over 27 million people (including this nation’s first serial murder, Herman Mudgett), visitors marveled at the scientific and technological advances to include a massive lighted tower supplied to the fair by a fledgling company calling itself General Electric (GE).

Visitors experienced many products for the first time that we take for granted today such as movies (courtesy of Thomas Edison), pancake-in-a-box kit (the retro house-slave-inspired look of “Aunt Jemima”) which suggested that the American economy was improving as to be able to afford such a luxury as pre-mixed breakfast and American life was speeding up so as to need a pre-mixed breakfast. There was the automatic dishwasher (invented by Josephine Cochrane), and two flavors of a new kind of candy (Juicy Fruit and Spearmint) called gum unveiled by a Chicago candy maker, William Wrigley, Jr. Visitors also tasted for the first time shredded wheat and diet soda. They rode the first Ferris wheel (invented by a fellow aptly named Ferris). They marveled at the vertical file (a business necessity), and they conserved their calories by riding on moveable sidewalks, as opposed to having to use the old fashioned form of locomotion—walking. American progress was showcased indeed!

Once the principles of science and technology were understood, then those principles could be applied to solve society’s problems. In the case of GE, the problem was human beings tended to have difficulties seeing in the dark, and candle, oil, or gas lights were not terribly efficient nor overtly powerful, hence the development of electric light (thanks in large measure to the work of Thomas Edison). Many of the inventions and products demonstrated at the Chicago fair suggested that the American pace of life was speeding up (you no longer had time to mix flour, salt, sugar, and baking powder hence the invention of Aunt Jemima) and that American pockets were getting deeper (buying “store bought” food products were not as cost effective as making the food yourself).

Nevertheless, although newly minted college graduates characterize the Progressive era, a college education was something that most Americans could not afford to pursue and was not necessary to obtain meaningful work. By 1900, only about 4 percent of Americans of traditional college ages were attending college. Those who could afford the cost and were accepted (most universities refused to matriculate women) tended to put their college educations to work for their communities through progressive reform such as Jane Addams and other social Progressives.

These Progressives were true-blue believers in the American society, politics, religion, and especially American capitalism. They were not Marxists, Communists, or anarchists. They were people who had an opportunity to gain formal education beyond the scope of what would pass today for a high school education, and that education tended to emphasize new intellectual fields. Those new intellectual fields tended to focus on society’s problems and how to fix those problems.

For example, after decades of dawn to dusk work on his Wisconsin farm, Hamlin Garland decided that college was the way through which he would elevate his life. He became a famous novelist using his own background as the basis for his publications, thus shedding light on the backbreaking, hand-to-mouth life style of American farmers, who Thomas Jefferson called “God’s chosen people.” A free-born black woman, Lucie Stanton Day, wanted to enlighten the plight of her people while also working to help them get off the farms so she obtained a college degree and moved to Mississippi where she spent the rest of her life teaching freed slaves. A young Sioux named Ohiyesa earned a medical degree from Boston University, changed his name to Dr. Charles Eastman, and married a white reformer named Elaine Goodale. The couple moved to Pine Ridge where they worked for the Sioux and fought for Indian rights.

What these Progressives had in common was the belief in the elevating power of education as well as their interest to give back to their communities. Most of the Progressive era reformers were not as involved with education as these examples might suggest, nonetheless the Progressive Era is characterized as identifying problems, using certain tools to address those problems, and applying corrective actions to put an end to those problems.

There were two basic, and sometimes opposing, views on how Progressive reform should take place: reform from within or reform from without. In the former, Progressives tended to believe that problems were local, and thus solutions (and actors) needed to be local. This grassroots, volunteer mentality was exceptionally widespread in wake of massive westward migration following the Civil War. An example of this type of Progressive reform was the Settlement House movement, led by a young college graduate, Jane Addams. Other Progressive reformers believed that problems could be best identified when viewed from above and thus solutions tended to be thorough when applied by those on high. An example of this top-down approach was President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt did not necessarily disagree with the problems that folks such as Addams identified; he just believed that he, as president, was in the best place and at the right time to fix those problems. There were various types of Progressive reform to include reforming the ills of society (such as tackling issues of poverty, immorality, or disease), addressing human foibles (such as alcoholism, gambling, or drug addiction), addressing inequalities in American life (such as women’s right to vote or own property), and altering American foreign policy (which was addressed in the previous chapter). This chapter examines domestic Progressive reform.

SOCIAL PROGRESSIVES

Women, more so than men, were typically the leaders of social reform activities during the Progressive Era. Many Americans considered women to be inherently more moral than men. Also women were seen as the domestic leaders of their households. Thus, women would use their God-given moral superiority as well as their inherent abilities in domesticity to clean up, reform, and fix their cities. Women used such domestic phraseology as “municipal housekeeping” to justify their new roles in the public arena. Women simply applied their inherent abilities of caring for their families against the backdrop of sin and corruption in cities.

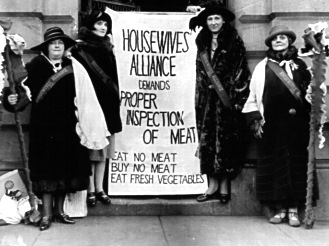

A good example of municipal housekeeping was the work of the National Housewives Alliance (NHA). The NHA called upon Americans to boycott all meat until the federal government agreed to inspect and certify the safety of the American meat industry. “Eat no meat. Buy no meat. Eat fresh vegetables” read one banner in a 1906 NHA protest in Maryland. As women were the ones in each home that made and served delicious, nutritious, and safe food, then women’s involvement in cleaning up the unsanitary conditions of the meat packing industry (evidenced by the 1906 Upton Sinclair novel entitled The Jungle) seemed to be a natural extension of their womanly duties. Interestingly enough, Sinclair’s message in his novel was lost on most Americans who came away from the book believing that government needed to clean up the meat industry. Instead, Sinclair’s main point was to shed light on the plight of immigrant laborers who were frequently abused, taken advantage of, and generally treated unequally in the meat packing industry.

Overwhelmingly, the mechanism through which women sought reform was federal, state, and local legislation. Thus, one characteristic of the Progressive era was a change in American ideals on the relationship between the government and the governed. Gone were the days of the early Gilded Age in which the federal government ran rough shot, uncontested, over Americans by sending out federal troops to put an end to strikes, consistently looked the other way when corporations gobbled up competition usually through violence, or allowed medicine based on opiates to be openly distributed. In other words, the problems of the Gilded Age, in the eyes of these Progressive reformers, were too unyielding for anyone but a government to tackle. This Gordian Knot would have to be cut by the Herculean efforts of an active, aggressive, and progressive federal government.

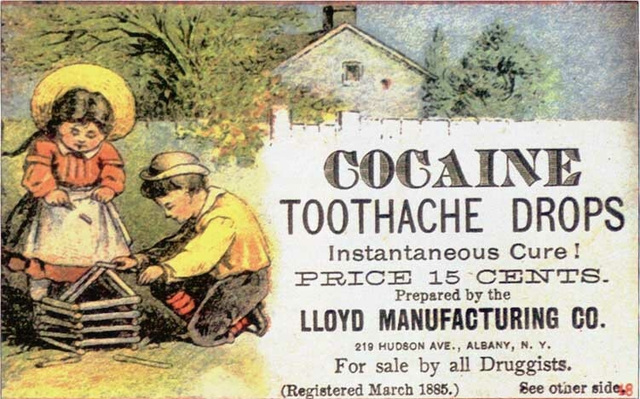

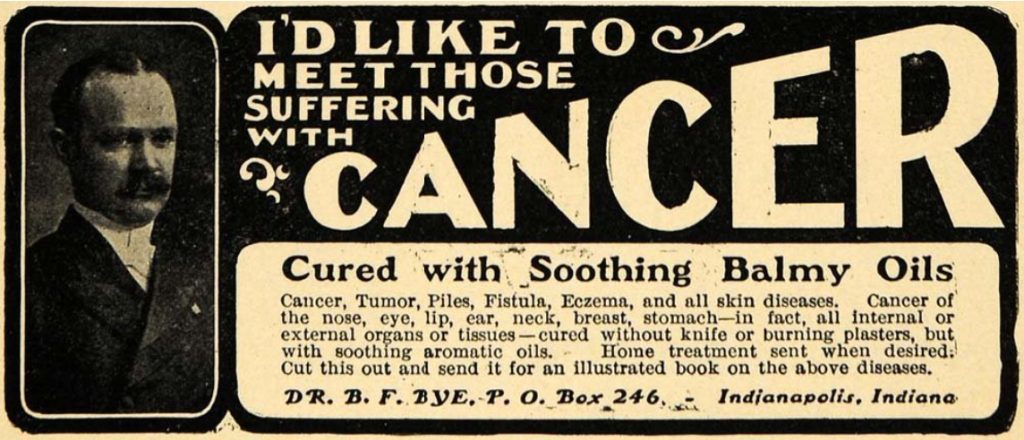

An example of success in getting the federal government to tackle these issues by regulating the industries that had, until the early twentieth century, been self-regulating was the Pure Food and Drug Act. Initially passed to assure American consumers about the ingredients advertised in their favorite medicines, this act led American consumer groups, political activists, and federal legislators to widen the scope to include outlawing ingredients and food handling practices that the federal government deemed as unsafe for human consumption.

Of course this change in the idea of the responsibilities of the federal government might not have happened through external pressures alone. Harvey Wiley, a chemist in the Bureau of Agriculture, published reports on adulterated food and medicine. Nonetheless, Wiley’s work inside the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt was not acted upon until women’s groups and publications (such as the Ladies Home Journal and Collier’s) picked up the baton of change by reporting how narcotics are typically used as the main active ingredient in so-called natural medicinal products, such as the wildly popular Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound.

Wiley believed that some chemical preservatives were safe and even necessary to ensure a healthy food supply. Thus, in 1902 he initiated an experiment called the “Hygienic Table” in which young male volunteers would knowingly eat small amounts of preservatives to prove their safety. Dubbed the “Poison Squad” by the press, these experiments went on for five years. As a true Progressive, Wiley believed that the producers of chemically altered food must prove the safety of their products and that all products must be clearly labeled so that American consumers could make fully knowledgeable choices. Wiley’s ideas would eventually become law in the United States.

Wiley believed that some chemical preservatives were safe and even necessary to ensure a healthy food supply. Thus, in 1902 he initiated an experiment called the “Hygienic Table” in which young male volunteers would knowingly eat small amounts of preservatives to prove their safety. Dubbed the “Poison Squad” by the press, these experiments went on for five years. As a true Progressive, Wiley believed that the producers of chemically altered food must prove the safety of their products and that all products must be clearly labeled so that American consumers could make fully knowledgeable choices. Wiley’s ideas would eventually become law in the United States.

Ultimately, one of the changes to American society that resulted from the popular press’s disclosures of unsafe, unsanitary food handling practices, the struggle within and without the federal government to get the Pure Food and Drug Act passed, and the push to enhance the scope of the act in the years leading up to World War I was that Americans began to see themselves as active consumers. Prior to the Progressive Era, many Americans upheld the Jeffersonian twin tenets of self-sufficiency and personal responsibility. You grew your own food, you made your own clothes and what you could not grow and what you could not make, you simply did without. Also, Americans viewed government action as a negative thing, which meant that many Americans opposed the establishment of professional, public police forces in their cities, as those police forces were of course armed representatives of “the government.” There was no federal or state agency to ensure the safety of anything Americans consumed, put on their bodies, or used in every day life. There were no tough, smart lawyers waiting to sue the pants of your employer when you became injured on the job or sue the drug manufacturers when your child died of consuming medicine laced with opiates. If you succeeded in life, you had yourself to thank. If you failed in life, you had yourself to blame.

In 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act. A good start at examining and regulating what Americans put into their bodies. But not all was well according to Valerie Gonzalez, a student of mine in the Spring of 2020:

In hopes of highlighting all the failures in regulation under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 Ruth Lamb and George Lerrick of the F.D.A produce a traveling exhibit referred to as the “Chamber of Horrors.[2] The exhibit gave examples of how the state of the Food and Drug act of 1906 made it impossible for the FDA to regulate certain products and practices. Their small exhibit made it possible for average Americans to understand what was wrong with their everyday products before getting hurt and the exhibit created an awareness on the lack of control the FDA had.

Despite the popular exhibit many Americans still suffered, in one particular case a cosmetic called Lash Lure was a product in which Hair Dye was marketed as being safe for dying eyebrow and eyelash hair.[3] The Pure food and Drug Act of 1906 did not extend to Cosmetics therefore cosmetic brands did not need to test their products for safety. Many women who used Lash Lure suffered ulcerations and cornea damage and for one woman, fatality. J.W Musser eventually had lost her sight from using Lash Lure and made her way to Washington to speak to Congress about the need for an expansion of regulations for cosmetics.[4]

Another way in which the FDA was inhibited from protecting American consumers was how the FDA could not hold companies responsible for hurting individuals unless there was evidence of harmful intent. BANBAR was a medicinal product offered to cure diabetes but in reality, had no effect on the patient’s diabetes. When taken to court the company provided testimonies from patients who assured the products effectiveness, in rebuttal the FDA provided the death certificates of those same patients who died of complications related to their diabetes.[5] Although the product did not do what it advertised the company was still allowed to sell BANBAR since the FDA needed to prove that the company produced the product with intention to harm according to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

Another duo who brought awareness of the then current lack of regulation was A. Kallet and F. Schlink who wrote 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs: Dangers in Everyday Foods, Drugs and Cosmetic in 1933.[6] In their book they argued how American Consumers were being treated as guinea pigs and safety and honestly was not being considered when companies were selling products. The book helped consumers really see how dishonest some of their favorite brands were and how dangerous products were so prevalent in their everyday life.[7]

The most infamous example of how poor product regulation was during this time is the distribution of the Elixir Sulfanilamide. As the tablet and powder version of the drug became more popular demand for the drug in liquid for arose and the chief chemist Harold Cole Watkins was able to adjust the chemical compounds to suit demands. They successfully tested the new concoction for flavor, appearance and fragrance but not safety which resulted in over 100 deaths throughout the states.[8] It was this incident that made Congress almost instantly pass the new 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act which expanded the FDA’s control over consumer products.[9][10]

However, the Progressive Era forced Americans to begin to look differently at their relationship to government, as well as their expectations from government. At stake were American ideals on liberty. No longer was it apparent that success or failure was necessarily in your own hands or of your own making. The playing field was horribly askew, and thus Americans, more than ever and in increasingly larger numbers, turned to their state and federal governments for assurances that their food and medicines were safe.

Of course, not all American politicians supported this new role for the federal government. Senator Albert Beveridge (R-IN), a supporter of the U.S. war in the Philippines on the grounds that the United States must advance all of America’s blessings to those poor, tired, huddled masses, feared that unless we helped them in their county, they would simply come to the United States seeking help. He declared the Pure Food and Drug Act to be “the most pronounced extension of federal power in every direction ever enacted.”

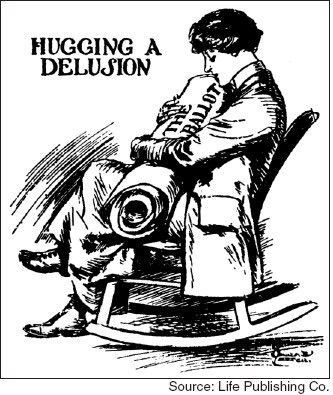

Success and failure are relative terms. Nonetheless, one reason why many of the Progressive ideas failed to achieve lasting results was because of the simplistic beliefs held by Progressives. For example, if women had the right to vote then they, as being more moral than men, would clean up politics. And, if they got rid of alcohol then gambling, divorce, and other social problems would necessarily disappear, as the Progressives believed that alcohol consumption was the root cause of so many problems in American society. In other words, maybe the Progressives tendency of embracing a single-villain theory was out of step with the complexities of humanity.

Temperance

One of the most iconic Progressive era reforms was the temperance movement. Like so many other reforms based on Gilded Age/Victorian morality, temperance roots had been firmly planted in the Washington Societies of the early nineteenth century. What makes these Progressive reformers different from earlier progressive reformers was those who supported a ban on alcohol created and maintained an effective, national organization. “Temperance is moderation in the things that are good and total abstinence from the things that are foul,” is what Frances Williard believed.

Created, in part, by Francis Willard in 1874 who held its presidency from 1879 until her premature death in 1898, the Women Christian’s Temperance Union (WCTU) urged state and federal politicians to ban the sale of alcohol. Like many other Progressive reformers, Willard was an educated person. She was a past president of Northwestern Female College, later accepting academic administrative positions at Northwestern University. She also worked for the Chicago Daily Post.

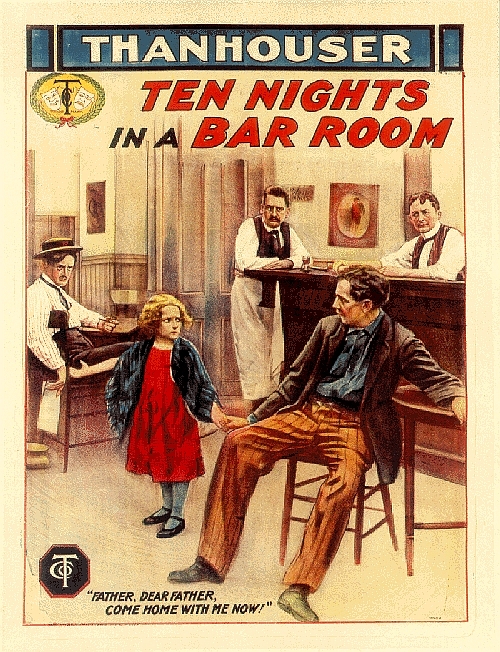

The WCTU spurred the creation of like organizations, such as the Anti-Saloon League, as well as strong-headed individuals such as the axe-wielding Carrie Nation. Protestant ministers used their pulpits on Sundays to preach the evils of alcohol. The antebellum novel, Ten Nights in a Barroom, by Timothy Shay Arthur became a national hit in the 1880s. The book examined how alcohol affected a small town family (as well as the small town). No big surprise here: drunk family members kill each other, a little girl pleads with her father to stop drinking (which he eventually does, but only on his daughter’s death bed; she dies after getting hit in the head by a thrown glass when she entered the saloon to plead with her father to come home) and in the end the whole town votes to close the saloon and outlaw liquor forever! The book’s popularity led to a silent film in 1913, a remake in 1922, and a talkie in 1931. The 1913 version was produced in part by the WCTU and was an early example of the effects of that new medium called motion pictures.

By 1916, twenty-one states had gone dry. Three years later, Americans altered the U.S. Constitution by adding the Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” There were major problems with the amendment, such as: What does “intoxicating” mean? What does “liquor” mean? Who will be in charge of enforcing this amendment? And, while the WCTU fought for decades to make it illegal for Americans to consume alcohol, the Eighteenth Amendment did not make it illegal to drink—only to make it, sell it, or transport it.

Shortly after Congress adopted the Eighteenth Amendment, the ambiguity of the amendment became apparent. Thus, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act (popularly referred to as the Volstead Act after one of its supporters, Andrew Volstead). This act defined alcohol, placed jurisdiction for the enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment squarely on the shoulders of the federal government and although it was still not against the law to consume alcohol, it was illegal to “possess” alcohol.

The fight over prohibition is a microcosm of a shift in American culture. Alcohol consumption had been viewed as more than merely socially unacceptable throughout the late nineteenth century, regardless of the fact that for Americans, alcohol was the safest beverage (unlike water or milk, no know pathogens can exist in alcohol). Native-born Americans saw alcohol has a moral evil that was becoming further entrenched in American life as a result of the American immigrant culture of those “new immigrants” (Catholics and Jews from eastern, southern, and central Europe). Likewise, alcohol was the root of all evil propelling American families on the road to financial and moral ruin.

The Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act failed to end alcoholism, the break up of families, and the disintegration of American souls. Will Rogers summed it up nicely when he said, “Why don’t they pass a constitutional amendment prohibiting anybody from learning anything? If it works as well as prohibition did, in five years Americans would be the smartest race of people on Earth.”

Prohibition of alcohol is a good example at how the Progressives were not always progressive: prohibition was an old idea and the Progressives were unable to surmise the potential effect of their actions: organized crime figures, bootleggers, and corrupt politicians fought each other for control of liquor distribution. Unscrupulous amateur brewers and distillers added methanol, ethanol, and other chemicals designed to quicken the fermentation process as well as to raise the alcohol level. Of course such chemicals were toxic and had been used as an alternative fuel sources since 1900. Prohibition wrought the same pain and suffering that the Progressive reformers were trying to remove by prohibiting the consumption of alcohol. The Eighteenth Amendment is the only Amendment to the US Constitution that restricted American liberties. Every Amendment extended liberties, except that one.

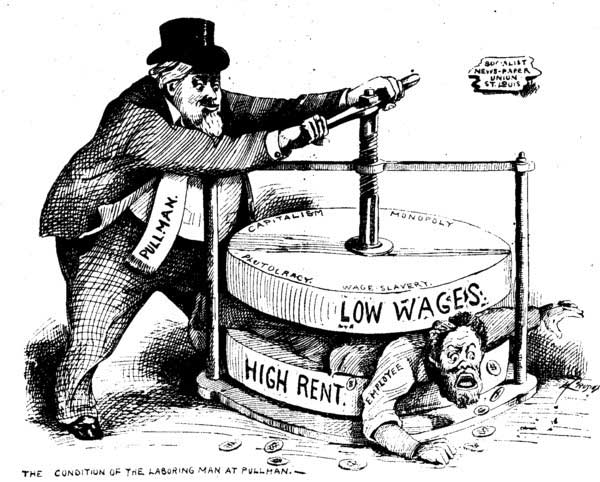

Labor Legislation

In 1912, Congress created the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations (CIR) with grudgingly acceptance from President William Taft. Taft was unable to get the Democratic-controlled Congress to allow his appointments, thus the real work of the CIR did not begin in earnest until the election of President Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat. Tasked with enquiring “into the general condition of labor in the principal industries of the United States, including agriculture, and especially in those which are carried on in corporate forms . . . into the growth of associations of employers and of wage earners and the effect of such associations upon the relations between employers and employees,” and chaired by Frank Walsh, the committee held hearings for over five months. The CIR consisted of members from labor, agriculture, and industry.

Unable to speak with one voice, the commission ultimately issued three separate reports, reflecting the three divergent positions of the committee members. Nonetheless, the reports were certainly neither shocking nor did they issue anything new or unknown to American labor. For decades American workers were routinely underpaid, fined for breaking a wide assortment of rules (such as laughing while at work), and shot by private armies, state militias, or even federal troops when workers went on strike. These matters were well known to American workers and were reported in the numerous papers that resulted from the commission’s work. It would have taken the twin punch of a massive domestic economic crisis paralleled by an unprecedented international crisis to push federal decision-makers to protect American workers against abuse they had been experiencing since the creation of the first mill in the 1780s.

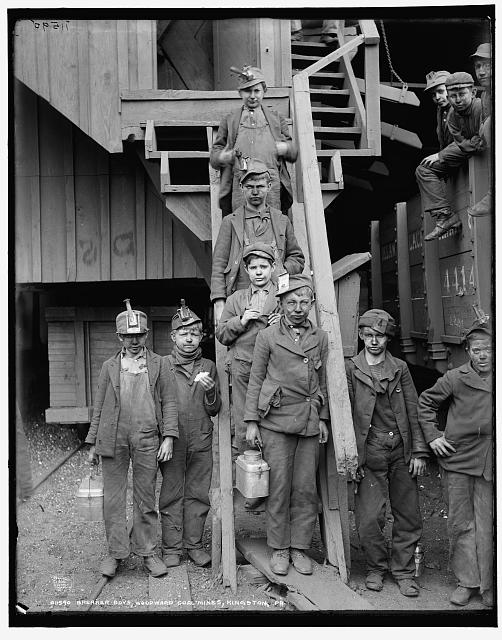

If any one group benefited from the Progressive era reforms, it possibly could have been children. Americans during the Gilded Age looked upon children rather differently than Americans view children today. Throughout most of U.S. history, children were simply short, young, adults. Children were an integral part of the household income regardless if the family lived on a farm or worked in a factory. In fact, in some career fields children were typically hired over adults, such as in mining, where their smaller, more nimble hands were beneficial. Children were also paid less than their adult counterparts and thus many factories tended to hire children as a way of increasing their profits.

We even look upon children differently today in regards to sex. The age of consent in many states was 12, and some even as low as 10, during the Gilded Age. Having consensual sex with a twelve-year-old today is not only socially repulsive but criminal as well.

Thus, not surprisingly, some reform revolved around the health and welfare of children. Women such as Florence Kelley (graduated from Cornell University) worked with state legislatures to enact policies that would prohibit children from working in dangerous settings, such as in mines. She helped launch the National Consumer League—an organization dedicated to socially responsible consumerism and alleviating the plight of overworked and underpaid factory workers. Yet, her first success was in regards to child labor in factories.

Due in part to her work with Addams as well as her work with the future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis in persuading the Supreme Court to support legislation curbing the number of hours women were allowed to work outside of the home, Kelley fought to both legally define a “child” and then to prohibit children from working the same hours and under the same conditions as adults. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the Illinois state legislature passed the nation’s first child labor law prohibiting children (defined as under 14) from working in factories. Illinois’ Progressive governor, John Altgeld, appointed Kelley as the state’s first female factory inspector, ensuring that all state laws were indeed being applied in Illinois’ factories.

In the legal system, children and adults tended to be treated as equals. Children, upon being found guilty of committing crimes, would be sentenced to serve their penalties in the same institutions that housed adult criminals. Thus came the juvenile court system in which social workers, lawyers and judges would be trained in and work with only juveniles. Children got their own jails. These reforms spread from the local, to the state, and eventually to the federal government.

During the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, the role of the federal government expanded to include protecting children as evidenced by the creation of the Children’s Bureau in 1912 within the Department of Labor. Reports from the Children’s Bureau, helped push through the Keating-Owen Act in 1916. This act prohibited the interstate commerce of commercial goods made by children. The act defined a child as a person no older than thirteen. Two years later the U.S. Supreme Court struck down this early attempt to define and protect children thus ending effective legislation until the administration of Franklin Roosevelt.

Settlement House Movement

So much of the Progressive Era reform was intimately connected to the massive waves of new immigrants and thus in one way the Progressive Era may be examined through the lens of fear: Native-born Americans feared the influx of European immigrants who came to this country without any history of democratic tradition, without any history of capitalism, with religious affiliations that caused many Americans to question the loyalty of these new immigrants, and with entrenched ideas of the acceptance of alcohol at a time when many Americans began to succeed in passing laws and changing minds regarding the consumption of alcohol. According to the census of 1900, 25 percent of the people living in the United States were foreign-born (in the early twenty-first century, the percentage of foreign-born is closer to 5 percent). Thus, you might wonder just how much of this reform was truly “progressive” to help these immigrants and how much of this reform was about controlling this ever-increasing influx of tired, poor, huddled masses?

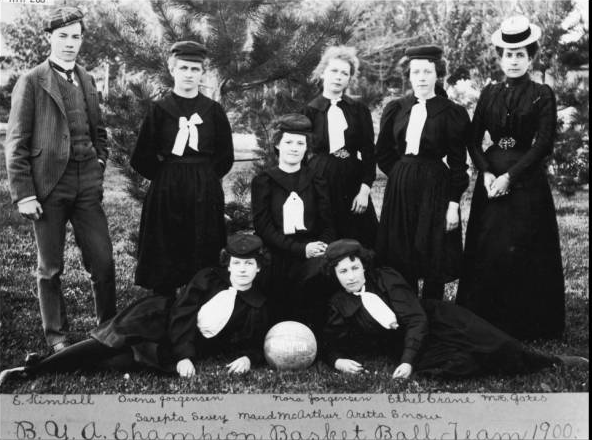

One reform that was clearly connected to the new immigrants was the Settlement House Movement. One of the latest and greatest paths of study after the Civil War was that of Social Work. As many Americans viewed women as naturally more moral than men, as many Americans believed that women’s God-given roles revolved around care-giving, and because women successfully entered the public arena in the years following the Civil War by using domestic housekeeping phraseology, it is not surprising that more women then men entered the field of Social work. Graduate students in social work at Smith College located in Northampton, Massachusetts (established in 1871) identified what they believed to be a problem in their part of the state: homelessness. In 1886 students rounded up homeless women, almost all of whom were foreign-born, and housed them in property bought by the college. They then put their social work training to the test. This fieldwork was so wildly popular that it spread from college campus to college campus and shortly was known as the College Settlement Movement.

By 1910, more than 400 of these settlement homes existed. The largest and possibly the most well known of these operations was located on Hull Street in Chicago. Created by a Progressive reformer who worked with Florence Kelley and others to enact protective legislation for children, Jane Addams developed her simple idea into a massive structure that provided training, education, and career opportunities for homeless, single-women and their children. Known as Hull House, Adams provided for the immigrant homeless of Chicago to include dressing like an American, cooking like an American, and introducing them to American past times such as the relatively new game of basketball. These women’s children also received assistance in a new kind of educational opportunity called a kindergarten. “Kindergarten,” or in English “a garden of children,” was, ironically, imported to the U.S. by German immigrants. Possibly due to Adams connections with the WCTU, women at Hull House were also instructed on the evils of alcohol.

Again, the line between assistance and social control was fine and the type of assistance that poor, immigrant women and their children received at Hull House certainly smacked of control. Hull House, ostensibly, helped immigrants in their transition from foreign ways to American ways. The Progressive reformers introduced these poor, tired, huddled masses to American democracy, American capitalism, and of course English.

A New American Culture?

By the early twentieth century, it seemed that these new immigrants were here to stay. Besides, factory owners seemed to need these laborers and thus a constant flow of immigrants might have been the lynchpin in transforming the America from an agricultural-based economy to an industrial-based economy in the decades between the failure of the Cook banking empire and the Great War. Paralleling the largest influx of immigration was the rise of another Progressive Era movement known as Americanization. Although the work of anti-immigration groups continued throughout the twentieth century (such as the American Protective Association, whose members attempted to prevent non-English speaking people from entering the United States), others sought to help immigrants succeed.

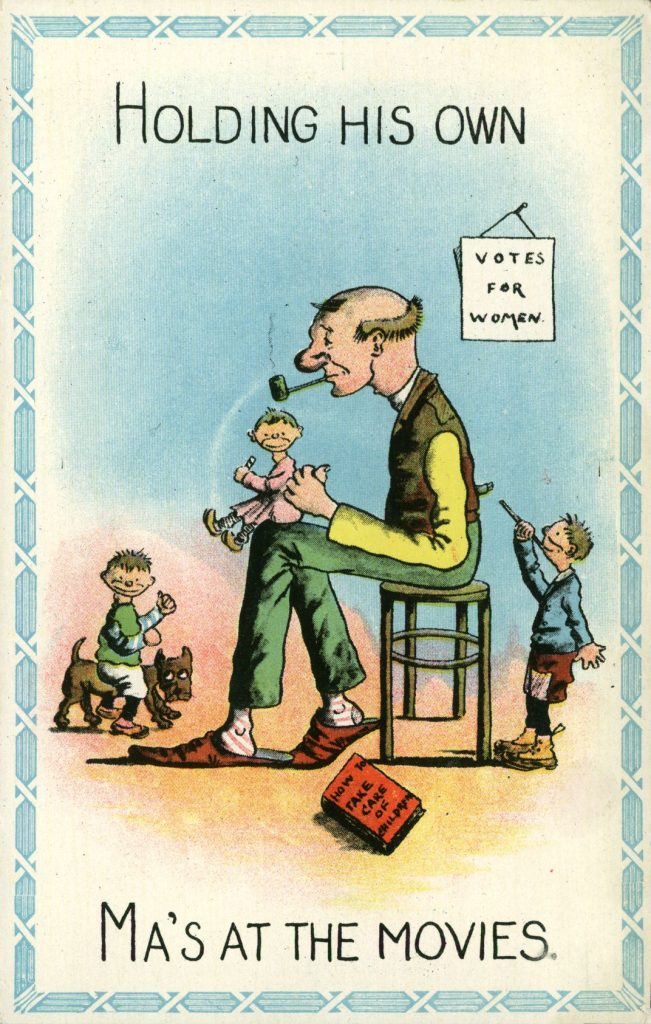

Better Movie Movement

Many of these immigrants enjoyed spending what little free time and extra money they might have accumulated on the new American cultural phenomenon known as the movies. There were no rating system, no rules, regulations, or policies that Hollywood was forced to follow. Instead, movie companies eventually developed and loosely adhered to their own list of dos and don’ts but not until after the Supreme Court ruling Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (1915) declared that motion pictures were not covered by the First Amendment, which meant that communities could (and did) pass laws prohibiting certain films from being shown in their theaters. No formal self-censorship codes were in place until 1930 and then the Production Code, as it was called, was not enforced until 1934.

Possibly because movies were relatively inexpensive, many native-born working poor and immigrants were attracted to theaters. In reaction to the lack of regulation combined with the particular crowd of people to be found in movie theaters, Progressive reforms (who were typically middle and upper class professionals) tried to compel state and federal governments to develop and impose an external ratings system upon Hollywood. This was one area in which reformers failed. Unable to rally governmental support, Progressive groups, such as the WCTU, simply made or produced their own movies. Ten Nights in a Barroom, The Tobacco Plague, and Safeguarding the Nation were all part of the “Better Movie Movement.” These films attempted to demonstrate how alcohol, smoking, and a weak military had an adverse affect upon this nation. What were really nothing more than long public service announcements, these movies, nonetheless, did not successfully make a change to American cultural ideas. Even in the 1930s “message movies” permeated American movie theaters. Films such as Cocaine Fiends and Reefer Madness are cult classics today but were serious attempts by a coalition of Hollywood and the federal government to curb American’s interest in opiates and marijuana.

Medicine

One of the successes of the Progressive era was the professionalization of the medical field. In the late nineteenth century, Americans successfully stopped the proliferation of patent medicines. Advertised as all natural, effective, and safe remedies for whatever ailed you, patent medicines were usually ineffective, dangerous, poisonous, or addictive drugs based on alcohol or opiates and if you consume enough of either, your troubles, albeit temporarily, just might be abated.

Still, in 1900 all you truly needed to be a medical doctor was a sign stating “the doctor is in.” And many of these doctors had no more medical training than did Lucy in the famous Charles Schultz Peanuts cartoons. While there were plenty of medical schools (such as the newly built Johns Hopkins or the 250-year-old Yale), you did not need a medical degree, or any degree, to work as a medical doctor.

One change to all of this quackery was the development of antiseptics by a British fellow named Lister. A result of external pressure from Progressive reforms and internal pressure from trained medical professionals, the American Medical Association (AMA) was formed in 1902 as a national organization. (The AMA traces its origins to the 1840s but does not become an effective, national organization until the Progressive Era.) In order to practice medicine in the United States you now had to belong to the AMA. In order to belong to the AMA you had to have obtained an undergraduate degree from an accredited institution and then successfully completed an approved medical degree.

In 1906 the AMA investigated 160 medical schools and rated them for their academic rigor. The report was published in 1910 and in 1912 the AMA began to undertake some of the report’s recommendations.

Not all Americans benefited from this professionalization of the medical corps. As most medical schools prohibited women and African Americans from attending, there were very few women and African American doctors after 1902. In addition, most poor and rural women tended to see untrained female medical practitioners while most black people sought medical assistance from black medical practitioners. Because these un-certified, unqualified, and untrained women and black doctors were prohibited from practicing medicine after 1902, many people in the United States lost access to even the most meager type of medical care upon the creation of the AMA.

Country Life Movement

The United States slowly transformed itself from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial society. According to the census of 1900, for the first time in U.S. history the majority of Americans considered themselves to be urban dwellers rather than rural inhabitants. Throughout this transformation, so too developed the idea that an urban lifestyle was more economically viable than a rural lifestyle. And by the early twentieth century, some Americans equated rural America with poverty and decay and urban America with wealth and progress. A good example of this urban-rural split was evidenced in a 1908 report issued by outgoing president Theodore Roosevelt. A rural existence lacked modern necessities such as electricity, factory-made farm equipment (such as John Deere’s latest steel plow or Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper), and a fully equipped kitchen. In regards to the later, Christine Frederick toured the rural South and West, introducing American women to modern conveniences such as dishwashers (introduced at the 1893 Chicago Fair), iceboxes, and new stoves. Frederick was not so much of a Progressive reformer who worked to bring rural women better management over their households, but rather Frederick worked for the big national corporations, such as Sears, J.C. Penny, and Montgomery Ward. She was a salesperson first and foremost but wrapped her sales pitches in the flag of Progressive reform.

Frederick did introduce “scientific management” to women all over this country both personally as well as through the pages of women’s magazines such as The Ladies Home Journal. In 1912 she wrote a four-part article entitled “The New Housekeeping: How it Helps the Woman Who Does Her Own Work.” In it, she offered advice on how to set up the washboard, sink, and table to their optimal heights for women to most effectively complete their work. Scientific management of the kitchen meant not only a place for everything but also the best place for every kitchen gadget, tool, and utensil:

A young bride recently showed me her new kitchen. “Isn’t it a beauty?” she exclaimed. It certainly had modern appliances of every kind, but her stove was in a recess of the kitchen at one end and her pantry was twenty feet away at the opposite end. Every time she wanted to use a frying pan she had to walk twenty feet to get it, and after using it she had to walk twenty feet to put it away.

This question of arrangement and the placing of tables and tools must be considered if the worker is to obtain the highest efficiency.

Frederick was no “Dear Abby” or Julia Child. Rather, she furthered the use of modern inventions in their most meaningful manner in order to help women embrace their God-given role as a domestic. Her promotion and advertising of American consumer culture, although seemingly new in the early twentieth century, certainly foreshadowed the consumer craze of the post-World War II generations.

Prostitution

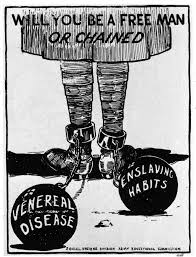

Progressive reformers connected physical illness with sin to push to end such diseases as syphilis. Syphilis was a rather common disease but by the late nineteenth century, many Americans saw the spread of this sexually transmitted disease as a morality issue: to have syphilis indicated a morally weak person. “Intolerable” was a common response to the widespread nature of this and similar diseases. Because this disease spread through sexual contact (unlike the popular misconceptions that syphilis is spread by shaking hands, using dirty toilet seats, or door knobs) many reformers began to attack what they believed to be the root of the syphilis epidemic: prostitutes.

Without wondering how prostitutes contracted the disease in order to spread it to their customers, Progressive reformers pushed local and state politicians to criminalize the sale of sex. Interestingly, it became illegal for women to work as prostitutes, but it was not illegal for men to engage prostitutes’ offerings, suggesting that the movement to stamp out sin and disease was based on the idea that women originated both the sin and thus the disease (a modern-day application of the Eve-Apple myth).

Jane Addams denounced the codification of prostitution, believing instead that government should examine the root causes of prostitution. Women only become prostitutes, Addams argued, because all respectable career options did not pay as much as prostitution. It was not unusual for immigrant women working in a New York City factory six days a week to make between $4 and $20 a month. Official government reports placed the average American woman’s wage at $6.67 per week.

Prostitutes made in a few minutes what it would take her factory-colleague weeks to make. For example, streetwalkers earned between $1 and $5 dollars per trick. An early-twentieth century investigation authored by the 61st Congress (1909-1911) entitled The Summary Report on the Condition of Women and Children Wage Earners in the United States, concluded that prostitutes who worked in private homes or brothels typically earned $20 a day while the owners of the brothels averaged $50,000 a year. Thus, if women could secure careers that paid them as much as prostitution, no woman would ever elect to become a prostitute, Addams theorized. To successfully end prostitution, Addams suggested that working women be paid the equivalent of their prostitute colleagues. If a telephone operator made as much as a prostitute, then women would swell the telephone operator ranks, thus ending prostitution, thus ending the spread of syphilis.

Needless to say, there was never a meaningful attempt to elevate the pay of working women to the level earned by prostitutes. Ultimately, prostitution was driven underground where criminal elements increasingly controlled the trade.

Woman Suffrage

In the decades following the Civil War, American women sought two parallel tracks in their attempt to achieve political equality. Some sought to amend the Constitution, allowing all women across the country to engage their right to vote through the efforts of the National Women’s Suffrage Association. Others believed that changes to society must come from within the borders of states and worked among state legislatures to pass laws allowing women the right to vote within their state elections, such as the American Women’s Suffrage Association. Before the end of the nineteenth century, these two groups came together and formed the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NASWA). They worked to get women the right to vote simultaneously at the state level and at the national level.

Of all the Progressive era reforms, there was possibly no more difficult fight than for women’s political equality. Women were prohibited from owning property through the Civil War. Women were, in some localities, allowed to vote in local board of education elections during the Gilded Age. Women authors of the late nineteenth century mirrored many of the ideas of equality first penned by the English author Mary Wollstonecraft in the years following the American War for Independence.

After the Civil War, thousands of Americans toured the world and upon their return hundreds wrote travel books: linear narratives of what they saw, usually injected American-Christian superiority and calls for help to reform the “heathen” all over the world, to include elevating the status of women. Palestine was a particularly important destination for American women travelers in the nineteenth century. These women tended to demonstrate to their readers the superiority of Protestant women by spreading rumors about Muslims. Some, such as Lucia A. Palmer, believed that Muslims were naturally bloodthirsty creatures who literally killed Christians, just for fun:

“The Mohammedan hates the Christian, and when he wishes to amuse himself, he takes a holiday and kills off a few hundred or a few thousand in Bulgaria, Palestine, or Armenia, in whichever country he chooses to hunt. Then the Christian world raises its hands in horror, and hold meetings, and dispatches to the Turkish government long demands and commands . . . and the Moslem answers by slaughtering more Christians.”

Their published travel writings suggest that many of these average American women supported suffrage as a social equalizer for the poor, tired, and downtrodden women of the Islamic Middle East. For example, when an American traveler named Kate Kraft was in Egypt, she called for a Woman’s Rights Convention because Egyptian women, unlike their American counterparts, were doing nothing to secure their right to vote.

Some women wrote, believing that publication was the manner through which women could add their voice to the public discussions on the major issues of their time. Another American traveler named Mary Barney, for example, believed that women should write about politics and government as a way of becoming active in a political climate in which women were prevented from partaking any active roles because they were not allowed to vote. One of the most important authors during the Progressive era was Charlotte Perkins Gillman. Gillman examined a wide assortment of gender equality issues in her works, such as The Yellow Wallpaper.

The Civil War-era suffrage leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were replaced by younger, slightly more aggressive, and almost always formally educated women such as Carrie Chapman Catt and Reverend Olympia Brown from Wisconsin. Yet, one of this country’s more influential suffrage supporters was the relatively unknown Emma Smith DeVoe.

DeVoe traveled the West from Illinois to Washington giving speeches and entertaining the crowds with Civil War-related songs, suggesting that proper northerners and Republicans support women’s right to vote while southerners and Democrats do not. Unlike the unflinching, stark, dowdy perception that many Americans held of Susan B. Anthony who remained unmarried and who dressed in a black dress and always had her hair pulled back in a severe bun, DeVoe was described as “womanly” for how she dressed (in the modern style), how she kept her hair, the fact that she was married, and the fact that DeVoe seemed to not preach to the crowds but rather to urge them to do the right thing by supporting women’s right to vote. She was a central reason behind the successful Washington campaign of 1912 and the eventual passage of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 1920. Unlike many of her Progressive colleagues, DeVoe’s devotion to women’s political rights did not end in 1920. Rather, she would continue her work to help women more efficiently wield the vote by creating the League of Women Voters.

Environmentalism

Suffragists join The Mountaineers outing to Mount Rainier and plant an A-Y-P Exposition flag and a “Votes For Women” banner at the summit of Columbia Crest on July 30, 1909.

The Progressive era is possibly most associated with the idea of launching the modern American conservation movement. Americans walked a fine line between the Jeffersonian ideal of living as independent yeoman farmers and gaining the wealth that came from urban living and industrialization. During the pre-Civil War industrial era, Americans worried about maintaining a balance between pristine lands of an agricultural-based economy and the inevitable ecological damage of an industrial-based economy. That was the paradox of industry. As Alexander De Tocqueville wrote, “from the filthy sewer, pure gold flows.”

During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln recognized Yosemite Valley as a “public park” in the 1864 Yosemite Act, creating the federal precedent for the inevitable creation of a national park system. After the Civil War some people tried to bring examples of the Jeffersonian ideal to the Hamiltonian reality of urban life, such as Frederick Law Olmstead, who created a green space in the middle of New York City. He called this space “Central Park,” and helped to launch a national movement to build parks in urban centers. The federal government picked up the baton in 1872 by creating the first national park: Yellowstone. By 1890 national parks reached the west coast with the establishment of Yosemite National Park, which is known as one of this nation’s first “wilderness parks” in part due to its 1200 square miles of rugged, pristine terrain. The Forest Reserves law of 1891 proscribed the president with the power to “withdraw and reserve public lands wholly or in part covered by timber or undergrowth” in order to be used for the good of all Americans.

These acts of Congress did not denote the authority tasked with administering the reserved lands and thus in 1897 Congress passed the Forest Management Act providing the Department of the Interior with the authority to regulate the use of reserved lands. The Bureau of Reclamation was created in 1902 to deal with the reality of water issues west of the Mississippi, in which the water tables were considerably lower than east of the Mississippi River. The federal government managed irrigation and other projects designed to best help Americans successfully settle the West. Once the irrigation projects were completed then the federal government would once again open the lands for settlement under the provisions of the 1863 Homestead Act.

In 1903 the federal government created the first national wildlife refuge, located in Florida, to help preserve and protect indigenous species. Two years later Congress created the U.S. Forest Service (originally under the Department of the Interior) and tasked that organization to manage the lands placed under reserve by the aptly named Reserve law of 1891. (Later the federal government will adopt the phrase “national forests” in place of “national reserves.”) Finally, Congress created the National Park Service in 1916, tasked with the management of all national parks (such as Mount Rainier in Washington, established in 1899), battlefields (such as Bear Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana), and monuments (such as the Alibates Flint Quarries in Texas).

“Conservation movement” and Hech-Hechy (1890-1910).

One of the lesser-known events during the Progressive era was known as the “Conservation movement.” In its infancy, and certainly viewed with more “progressive” twenty-first century eyes, the conservation movement of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries might appear to be backward. Probably the two most important names attached to this reform were President Theodore Roosevelt and his Secretary of the Interior, Gifford Pinchot.

Pinchot began his federal career as the head of the Division of Forestry within the Department of Agriculture in 1898. Roosevelt, being quite concerned about conservation and the West, appointed Pinchot to investigate reports of the federal government leasing federal lands to ranchers. In 1904, Pinchot’s influence in the Roosevelt administration resulted in Pinchot wrestling control of the national forests away from the Department of the Interior. A few years later Pinchot’s attempt to gain control of all national parks, monuments, forests, and battlefields failed, and in the backlash a new, permanent oversight of the National Parks Service was created under the auspices of the Department of the Interior.

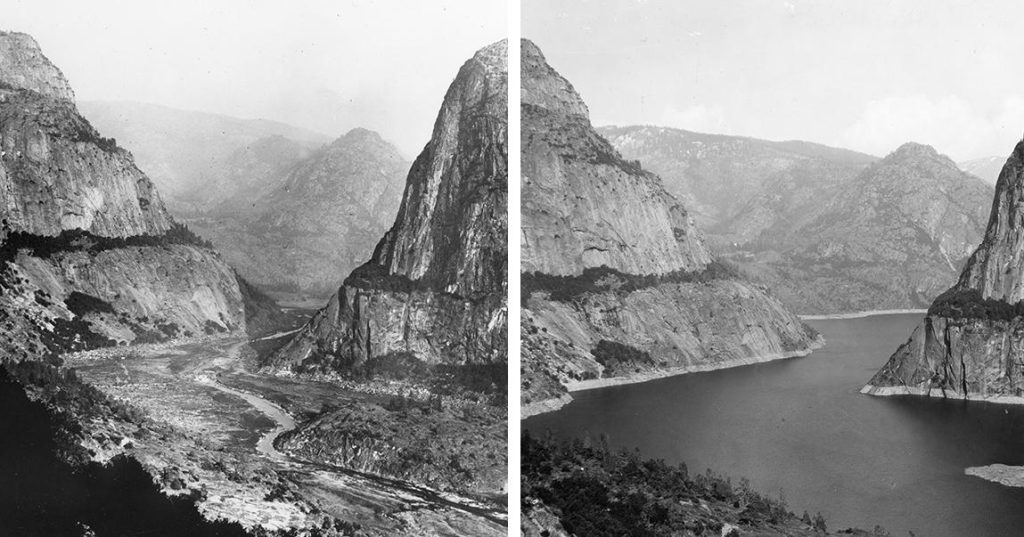

The Roosevelt-Pinchot team’s most prolific battle was over the damming (and the potential consequences) of a strip of land in California known as Hetch Hetchy. Following the 1906 earthquake, the city of San Francisco sought to dam part of Yosemite in order to create a man-made lake to be used as a fresh water supply. Roosevelt and Pinchot favored the project, while people such as John Muir (who created the Sierra Club in 1892) opposed destroying what he equated as a natural cathedral or temple. Interestingly enough, both Pinchot and Roosevelt were friends with Muir earlier in their careers. The federal government won and an act of Congress authorized the construction of a dam that partially flooded the Yosemite Valley.

The creation of Yosemite National Park and the flooding of the valley did not happen without its critics, to include the untold numbers of Americans and Indians who relied on game, water, and timber from Yosemite for their survival. Many of those people refused to adhere to artificial lines drawn in maps and thus they continued to hunt game on the park, fell trees on the park, and seek their fresh water sources from within the park. The US military was initially tasked with the park’s security but by 1916 the federal government created the National Park Service to manage all aspects of these national resources, to include keeping people from hunting or taking other resources from within the boundaries of the park. Without federal protection, it seems that some Americans do not see the value of maintaining these natural wonders for others. For example, during the 2018-2019 government shut down, there were no park rangers or any federal officers in some of the national parks and eight rangers were assigned to patrol the 1200 square miles Joshua Tree National Park in the Mojave and Colorado deserts. People attacked the iconic trees, chopping them down, “illegally off-roading and spray painting rocks.”[11]

THE PROGRESSIVE PRESIDENTS AND POLITICAL PROGRESSIVENESS

Overwhelmingly, Progressives held an evangelical zeal (and many had backgrounds in evangelical movements) in their beliefs that not only were they able to identify problems but that they had the tools necessary to fix those problems. Progressives, however, differed on whom would lead the reform: reform from below (volunteer or community-led) or reform from above (government-led). Not surprisingly, some American presidents believed that problems were best identified and then corrected by themselves. Traditionally, the Progressive era American presidents were Theodore Roosevelt, his handpicked successor William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson.

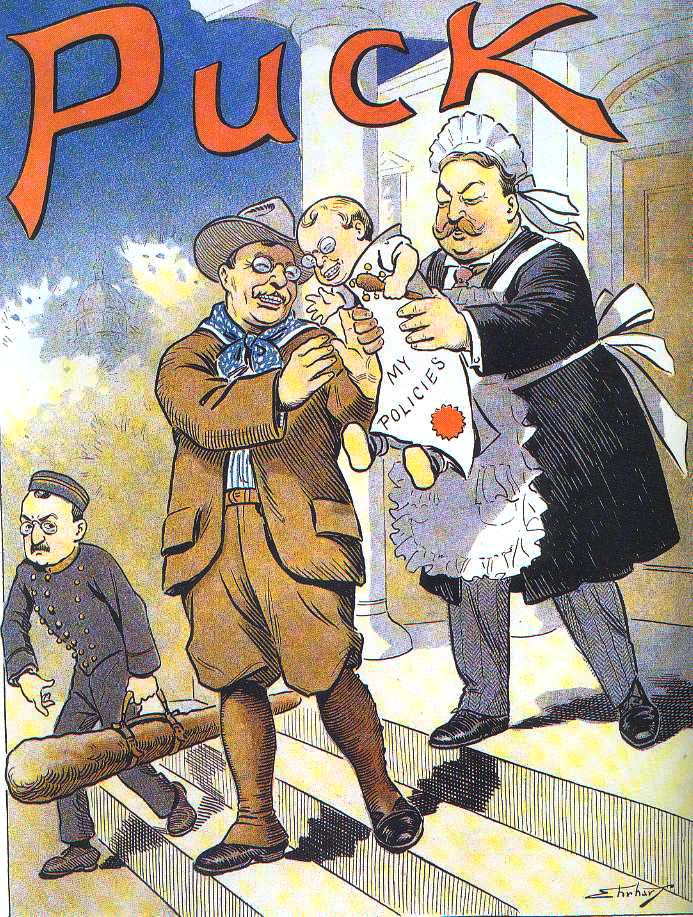

TEDDY ROOSEVELT: The First Progressive President

The Roosevelt family was one of the oldest and wealthiest families in the United States. Being able to trace his ancestry in this country back to the Mayflower, Roosevelt belonged to an elite group of American families. His aristocratic background propelled him through Harvard. After a brief career in the New York legislature he became the second in charge of the Department of the Navy in 1897.

Roosevelt was a bold, brash, and at times larger-than-life figure who lived what he called the “manly life” (daily exercise, engaging in sports, and being active on the world’s stage). Not without reservation, the Republican leadership offered the vice presidency to Roosevelt in 1898, following his brief yet wildly advertised stint in a private military unit during the Spanish-American War. Leon Czolgosz elevated Roosevelt to the presidency when, in 1901, he assassinated President William McKinley.

Roosevelt’s progressive ideas had their genesis while serving the people of New York. Roosevelt believed that he, as president, was best suited to both identify and then apply corrective measures. Thus he was not a fan of the new journalists who researched, wrote, and published exposes against abuses in American industries such as oil, alcohol, and dairy. One of these “muckrakers,” as Roosevelt called those who dug in the dirt of business practices, was a woman named Ida Tarbell. Tarbell worked for what was arguably the most well known investigative magazine of its time–McClure’s. The magazine published articles exposing problems in the dairy industry (thousands of infants and elderly people died each year of contaminated milk), but Tarbell’s work on Standard Oil set the bar for investigative reporting. Tarbell discovered that the Rockefeller family’s rise to the top had less to do with a Puritan work ethic and more to do with corruption, bullying, and outright monopolizing the industry. Tarbell’s work led the federal government’s dismantling of Standard Oil and winning the nickname “trust buster” for Roosevelt.

Roosevelt did not believe that all monopolies were inherently bad. Rather, and in step with many U.S. decision-makers and federal judges, if monopolies produced a good product at a fair price, Roosevelt et al tended to leave them alone. What Roosevelt did believe in was the inherent power of the federal government to even the playing field, thus he supported federal laws that regulated business, such as the Hepburn Bill.

Roosevelt also believed in the power of the president (or at least the power of himself as president) to become personally involved in regulating industry and he did so in the 1902 Anthracite coal strike and the Northern Securities investigation two years later.

WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT: Dollar Diplomacy

Taft was Roosevelt’s handpicked successor to lead the Republican Party as well as the nation. As a president, Taft did not as much as continue Roosevelt’s policies in regards to the economy, business regulation, and foreign policy than he developed what was seen at that time as possibly something new. Taft supported the idea that American political, social, religious, and economic strategies would be most effectively spread throughout the world by American businesses as the tip of his spear.

Under the presidency of Taft, the U.S. began loaning large sums of money to Latin American countries, such as Nicaragua, in order to grease the wheels, so to speak, for American companies to control local production, such as the infamous American agriculture company United Fruit. Today Taft would fit in, philosophically, with Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Bremer, Dick Chaney and others known as Neo-Cons in the early twenty-first century. On the domestic side of his presidency, Taft was involved with issues pertaining to alcohol, labor and business regulation, conservation, race and immigration.

Taft never officially identified his position on the government’s role regarding the regulation of the alcohol industry, however as president Taft did veto a congressional measure that prohibited interstate commerce of alcohol into states that had prohibited the consumption of alcohol within their borders, such as Georgia, Alabama, Oklahoma, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kansas. Known as the Webb Act, Congress overrode Taft’s veto. It is difficult to say with any certainty if Taft’s veto supported the idea that the federal government should not be involved in matters of the states or if he believed that the federal government should not be involved in regulating the liquor industry.

Roosevelt’s personal mediation of the Anthracite coal strike would not be repeated during Taft’s administration. Rather, Taft allowed courts to decide issues pertaining to labor yet he tended to use the power of the executive branch to enforce the Sherman Act. Ironically, this nation’s “Trust Buster” was Taft, who filed more suits against American monopolies than his predecessor, who was given that nickname as a result of his administration’s fight to break up Standard Oil. Standard Oil was to Roosevelt as U.S. Steel was to Taft. Taft’s attempts to break up U.S. Steel (a corporation established when Andrew Carnegie sold nearly all of his U.S. holdings to men such as Charles Schwab, John David Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan) were as successful as the break up of Standard Oil. While Taft won a few legal battles, Schwab, Rockefeller, and Morgan continued to enjoy nearly unchecked power, authority and wealth as Taft’s one-term administration came to a close in 1912.

Taft’s history in the Progressive conservation movement is even less effective than his dealings with labor or big business. The president fired Teddy Roosevelt’s right-hand man in the conservation movement, Gifford Pinchot, ultimately costing the Republicans needed votes among environmental and conservative-minded western voters. However, Taft tended to hold true to the notion that the federal government’s roles in regulating the environment must be severely limited, instead wanting states to take the lead in conservation.

Taft, adhering to a hands-off policy established by the Rutherford B. Hays in 1877 and possibly due to his belief in the inherent power of state governments, typically refused to get involved in racial matters such as segregation or lynching. Although just before leaving office in 1913, Taft vetoed a resolution that would have allowed the federal government to prohibit entrance to the U.S. for any immigrant who failed to demonstrate a basic literacy in English. Taft’s record on progressive domestic affairs is scant, at best, in part due to his unpopularity at home. Typically, when American presidents are incapable of forwarding meaningful domestic agendas, they tend to become more involved in foreign ventures, where presidents wield more power and are outside of the direct control of the legislative branch of the government.

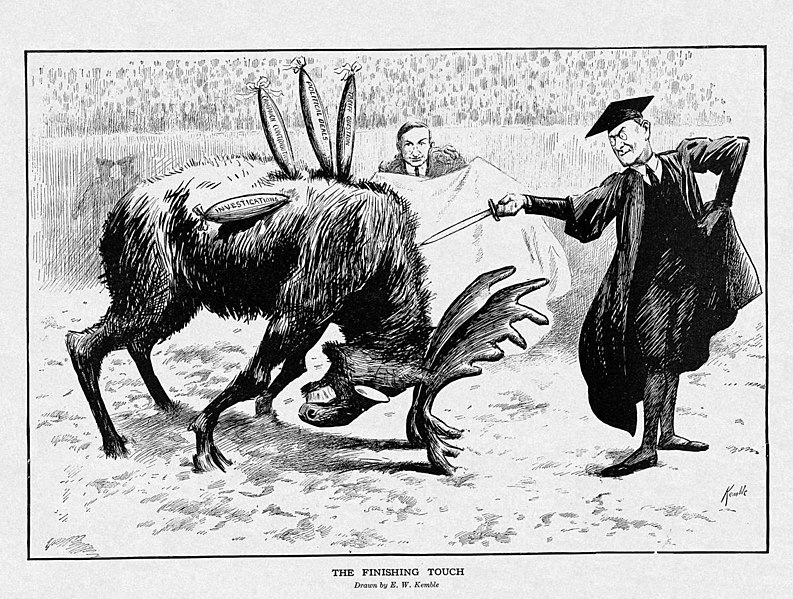

WOODROW WILSON: The Crusader President

The Progressive era president most closely associated with establishing the relationship between the federal government and the economy as well as creating the now widespread American belief in the necessity of the federal government to control the U.S. economy was Woodrow Wilson.

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act, as demonstrated in the Taft’s administration’s inability to effectively regulate monopolies, was narrowly applied by the court to the extent that only monopolies that were illegally established could be confronted by the federal government. To close this loophole, Congress passed and Wilson signed into law the Clayton Act. Wilson, when campaigning in 1912, promised Americans that as president he would more aggressively than his predecessors attack all constraint of trade in order to create an open market. (In 1917 Wilson called for the creation of an international economic system unconstrained by even tariffs.) The Clayton Act fell short of Wilson’s election-year promises. Instead of forging a stronger weapon, the Clayton Act merely enacted more harsh penalties for corporations that were found guilty of breaking the Sherman Act.

Wilson was successful, however, in getting legislation passed that would assist American workers. In 1914, and by the Progressive Wisconsin Republican “Fighting” Bob La Follette, the La Follette-Peters Act limited women garment workers in Washington D.C. to working eight hours per day. In 1915 La Follette’s Seaman’s Act tried to help American sailors by restricting their working hours and enhancing their working conditions. The Adamson Act prohibited American rail workers from working more than eight hours per day. The first measure was adopted in order to protect the traditionally-viewed job of women as caregivers and homemakers, while the other two acts were passed for safety reasons. Wilson supported the adoption of these measures.

Wilson also supported the expansion of the scope and depth of the federal government in very particular instances, such as when he signed into law the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The piece of Progressive legislation, authored by Representative Carter Glass (D-VA) and Senator Robert Owen (D-OK), provided “for the establishment of Federal reserve banks, to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes.” Interestingly enough, Wilson did not support the legislation on the idea that a singular, federally-regulated currency would help consumers, but rather the adoption of the act would benefit business. Unlike popular myth, the Federal Reserve was not under the complete control of the federal government but rather consisted of a coalition of federal and private banks. Private banks that joined the Federal Reserve system were granted certain perks, such as access to low-interest loans. The Act did have its critics, such as Representative (R-MN) Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr. who called the Federal Reserve “the most gigantic trust on earth . . . [and] . . . the worst legislative crime of the ages.” Lindbergh will be better known for being the father of the first person to cross the Atlantic by airplane: Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., who was also a supporter of Nazi Germany during the 1940s.

Finally, Wilson oversaw the passage of four amendments to the U.S. Constitution during his two terms. The Sixteenth Amendment authorized the federal government to adopt and collect a national income tax. The Seventeenth Amendment provided for the direct and popular election of U.S. Senators. The Eighteenth Amendment, aka Prohibition, made it illegal to do just about anything with alcohol, except to consume it. And, the Nineteenth Amendment allowed universal suffrage.

LIMITS of PROGRESSIVISM:

Progressive reformers certainly were unable to effect positive change for all Americans and in all aspects of life, liberty, and happiness. There were three groups of Americans who typically did not realize change or were not the focus of Progressive reformers: Blacks, Indians, and Women.

African Americans