17 Reconstruction I: Failing to Transform Society, Politics, and the Economy and, Some of the People Who Made Failure Possible

Reconstruction I

Jim Ross-Nazzal, PhD and Students

“Education was ‘the next best thing to liberty.'”[1]

Reconstruction was about the massive change in the country’s economics, politics, and society from a slave-labor to a free labor socio-economy. In a very short period of time 3.5 million slaves were free and quickly became citizens with approximately half of those being allowed to vote. Changes in societal views take time, however, and events in Charlottesville, Virginia in August of 2017 demonstrate that those feelings of and support for white supremacy have still not been excised from American society.[2]

Southerners wanted to get their accounts of the war out. Alexander Stephens published a legal argument thesis in which the South had to fight to protect the Constitution. Then Jefferson Davis published his two-volume account arguing that the South was merely trying to hold back the ever-growing, ever-powerful federal government. In both instances, the South was the hero. While the federal government was the villain.

Things to consider in this chapter. What would the North do? Why was Presidential Reconstruction abandoned in favor of Congressional Reconstruction? Why did Congress opt for Radical Reconstruction? What was Radical Reconstruction? Why did the North, in the 1870s, abandon Radical Reconstruction? And, (Part III) was Reconstruction a success?

Northern conceptions, by 1865: The Spirit of Appomattox. Soldiers prayed together at the official surrender of Lee to Grant. Union troops saluted Lee and the Confederate troops and Lincoln’s call to “bind the nation’s wounds.”

Righteous indignation: The South caused the war. They were slave holders. Slavery was immoral. Slave owners supported the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dred Scott, the South is guilty of war crimes (Andersonville) thus southerners are evil and must be punished.

The fruits of victory must be preserved. The Republican party saved the Union. The Republican party is the party of the North, Abe’s party. The Republicans cannot let the South come back status quo ante. Republicans need black voters, black representatives and black senators. Republicans must rebuild the Union, safely. This is why Congress will abandon Presidential Reconstruction in favor of Congressional Reconstruction.

Those attitudes are shaped by that northerners believed southerners are doing as reported by northern newspapers. For example, the anti-Union sentiment reported in Richmond, Virginia, the anti-black sentiment of the Confederate soldiers and politicians, and prisoner of war camps such as Andersonville. Henry Wirz, the director of Andersonville, is executed for war crimes. Wirz is the only Confederate executed for participation in the war. Jeff Davis is first imprisoned in chains, then eventually released. And Lee loses his estate. Wirz’s execution might have something to do with the fact that he was a foreigner, suggesting a bit of xenophobia?

The Union experienced 360,000 killed and 275,000 wounded (out of 1.5 million in the army) versus 258,000 killed and 100,000 killed (out of 1 million in the army) of the Confederacy. That is a 40% casualty rate. That is certainly going to affect Reconstruction. In comparison, World War I was 2% and World War II was 3% casualty rate.

Northern ministers’ sermons of 1865 said that God wanted southerners punished, that Lincoln was too good, nice, and gentle to deal with the southern ruffians and thus Andrew Johnson was now part of God’s plan. Abraham Ryan was a Catholic priest who served with the Confederate army. He wrote poems on the “Lost Cause.” His most famous being The Conquered Banner in which Ryan wrote that the tattered stars and bars were symbolic of the southern defeat.[3]

Federal government’s ideas on Reconstruction began before the War ended. President Lincoln’s proposal was known as the 10% Plan. 10% of the people who voted in the 1860 election had to take a loyalty oath to the US. They had to promise never to raise their hands again against the United States. The oath, thus, was forward looking. Each state had to write new constitutions that removed all aspects of slavery. At that time, the ex-Confederate states would be welcomed back into the Union. Congress believed Lincoln’s plan was too lenient. What Congress did not readily accept was that Lincoln’s plan was devised to grow the Republican party in the South.[4]

Lincoln did have other ideas, or, floated various trial balloons. For example, Lincoln once wrote that in Tennessee, Andrew Johnson consider disenfranchising anyone who remained disloyal to the Union.

In an 1864 letter to Gen. James Wadsworth, he wrote that peace would be sealed by: “universal amnesty . . . accompanied with universal suffrage.[5] and “The restoration of the Rebel States to the Union must rest upon the principle of civil and political equality of the both races; and it must be sealed by general amnesty.”[6]

In Lincoln’s letter to governor-elect Michael Hahn on Louisiana, he considered extending suffrage to “intelligent” Blacks and to those who fought “gallantly” for their freedom.[7]

Did these letters suggest that Lincoln was undecided or that he wanted to test the waters of what would be acceptable?

In 1864 Congress proposed the Wade-Davis Bill. Wade-David also included an oath, but the oath was backward looking. 50% of the ex-Confederates who voted in the 1860 election had to pledge that they did not take up arms against the US. Military governors would rule the South and the South would be treated as conquered territory. The measure was pocket vetoed by Lincoln. What Lincoln did not like was that Congress tended to view the South as conquered territory.

Lincoln’s second inaugural address (March of 1865) seemed to signal his support for his 10% plan: “With malice towards none.” There would be a swift political peace between North and South and a social peace between whites and blacks. Universal amnesty for whites and universal male suffrage for the ex-slaves. Lincoln’s assassination changed that.

There were problems facing the United States. How does the federal government deal with the political reality of the ex-Confederate states? Are they foreign entities because they seceded or were they simply rebellious and secession never took place because secession was unconstitutional? What about the economic devastation of the South and how does the federal government transform the South’s economy from a slave based agricultural system to a labor based agricultural system? Finally, what about the ex-slaves? What are their immediate and long-term needs and how will those needs be met and by whom?

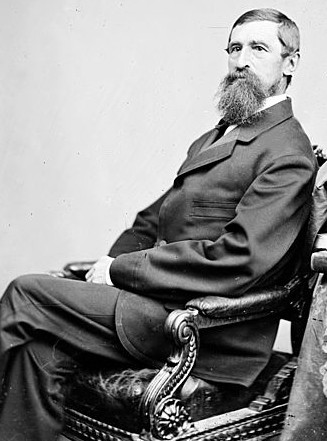

Andrew Johnson, a Democrat Senator, and a well-known alcoholic, from Tennessee, who remained loyal to the Union, became Lincoln’s running mate in the 1864 election. Upon Lincoln’s death, this southern Democrat became president. He launched Presidential Reconstruction in 1865 arguing that secession was illegal, hence the southern states never really left the Union. The South’s leaders simply led a rebellion. Those leaders would be pardoned by Johnson and the ex-Confederate citizens had to take a loyalty oath, not unlike the one proposed by Lincoln.

Johnson also stated that the ex-Confederate states had to elect Representatives and Senators and to abolish slavery in their state’s constitutions. While northern Democrats supported Johnson’s ideas, Radical Republicans rejected Johnson’s plan. The Radical Republicans were upset that although the Republicans won the White House in the 1864 election, a Democrat was currently in the Oval Office. They believed that Johnson was not averse to slavery and so they felt that Johnson’s reconstruction plan was too lenient. Radical Republicans felt that southerners needed to be punished -a feeling of righteous indignation.

Another idea was that states committed “suicide” by seceding and so they needed to go through Congress, just as any new state had to do so in order to join the US. Charles Sumner supported this idea.

Many southern governments ignored Johnson’s ideas on Reconstruction and went ahead and elected former Confederate leaders to public office. There was widespread resentment in the South for the creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau as well as northern troops stationed throughout the South. And, there was widespread resentment for Congressional Reconstruction’s laws, such as the Civil Rights Act that prohibited Black Codes as southerners saw Black Codes as inherent aspects of the racial hierarchy of the South. The Civil Rights Act also granted citizenship to the ex-slaves and outlawed discrimination based on race.

Republicans did not speak with one voice in Congress. Radical Republicans (like Charles Sumner) called for some sort of political role for the ex-slaves (usually suffrage), while moderates were undecided on black suffrage, but they moved into the Radical camp due to disillusion with President Johnson’s antics. Lyman Trumbull is an example of a moderate.

The Freedmen’s Bureau (Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Land) was created on March 3rd, 1865 in the War Department. General O.O. Howard was its first director and he emphasized immediate relief (food, shelter, medical needs). Howard University is named after him. Howard oversaw the construction of Freedmen schools. Thousands of white northern women came to the South to teach at those schools. Those women, and others who came from the North, were known as carpetbaggers. Universities were also established so the best of the ex-slaves could be prepared to lead the black communities. Universities such as Fisk and Southern. The Freedmen’s Bureau functioned in all 15 slave states, passed out 150,000 rations per day (approximately 22 million meals in total) established 100 hospitals which served 500,000 patients, and established 4,000 schools.

The Bureau of Refugees Abandoned Lands, and Freedmen, sought to address all three of those major issues. The Bureau would bring immediate relief to the ex-salves in the form of food and shelter, build schools, and recruit teachers (from the North). Lyman Trumball, as well as other moderate Republicans, moved into the Radical Republican camp due to Johnson’s veto of this and the Civil Rights veto. Lincoln actually signed this Bill into law in 1865 to last one year so Trumball, et all, tried to extend the bill for a few more years.[8]

The Bureau sought to help the ex-slaves become independent farmer as quickly as possible so the Bureau secured loans from local banks for the ex-slaves to purchase everything they needed from land to tools. Black farmers became sharecroppers -having to pay a share of their crop back to the bank (usually 10%) in order to pay off the loan as quickly as a decade. The “annual autumnal raids”, as Grant called them, scared off enough black farmers that some could not harvest, which meant they lost their lands. White farmers would be waiting to purchase cheap land but the ex-slaves till had a debt to the bank and thus were required to work on the land. Debt was passed down so that the children of the original debtors had then to pay off the debt upon the death of the original debtor. This cycle would continue until the first massive wave of migration up North during the Great War and then again during the Good War. Corruption and unfair military rulers spelled an end to the Bureau.

For the most part, Congress ignored Johnson’s ideas and went about passing bills they deemed necessary to implement social, political, and economic change in the South both to offer assistance for the ex-slaves (who were called Freemen) and the landless southerners and punishment for the political and economic elite of Southern society. For example, Congress passed the Civil Rights bill in early 1866, which Johnson vetoed. Johnson explained that he vetoed the bill because it protected blacks more than poor whites, the bill interfered with states’ rights, and expanded the federal system of limited powers, and was constitutionally questionable. Congress overrode the veto on the Civil Rights bill and passed a revised version of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill. The Freedmen’s Bureau bill extended the life of the agency formed to arrange assistance of food, shelter, and other needs in the transformation from slavery to freedom for the slaves. The Civil Rights bill nullified the Black Codes.

Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Bill while defending the US Constitution, he claimed that Radical Republicans were conspirators. Congress overrode the veto in just seven days. On February 22nd, 1866, President Johnson hosted the annual Washington’s Birthday celebration. He toasted Washington. Normally the toast is to commemorate all the wonderful things that Washington did, remind the guests all the wonderful things the current president did and thus state that the current president is wonderful, just like Washington. Instead of that, Johnson launched into an unhinged tirade claiming that Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner were out to kill him. George Templeton Strong proclaimed, “He’s Drunk Again”. The number of Radical Republicans swelled. Hostility towards Johnson increased.

Back Codes were laws passed in the South (originating in Mississippi) during Presidential Reconstruction in order to continue a “slave-like” system. For example, authorities could arrest and detain blacks at will. Punishment for the smallest of infractions could mean being rented out to landowners as laborers. Freedmen need passes from their employers to travel away from their place of employment. Employers were allowed to whip their black employees. Freedmen could not own property. And, Freedmen were not allowed their Constitutional rights to peaceably assemble or free speech.[9]

Mississippi (and other southern states) established their governments through Johnson’s May of 1865 declaration, appointed William W. Holden as governor of Mississippi (a southerner who supported the Union -a scalawag). Mississippi was the only state that, as Johnson declared, had completed his requirements for Reconstruction when Congress returned from its summer recess. Congress then created the Joint Committee on Reconstruction to investigate on December 4th, 1865. Led by William Pitt Fessenden, the Committee was tasked with asserting Congress’ role in Reconstruction. Lyman Trumbull was an active member of the Committee. He authored the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, as well as the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Act. He hoped, initially, to work with President Johnson. That is, until Johnson declared Reconstruction over with on December 6th, 1865.

By the middle of 1866 animosity between Johnson and Congress became public, especially over the fight on the Fourteenth Amendment. The Thirteenth Amendment (prohibition on slavery) passed in 1865 but Johnson did not support allowing the ex-slaves to be granted citizenship. As originally drafted, the Fourteenth Amendment grated universal male suffrage and prohibited anyone who joined the Confederacy from holding state or federal public office. Eventually, the Fourteenth Amendment will be adopted with only the citizenship part. The Fifteenth Amendment will give universal male suffrage. There will never be a federal prohibition on ex Confederates from holding public offices.

The election of 1866 brought more Radical Republicans to office, resulting in a veto-proof majority in both houses of Congress. The new Congress got to work. First, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act dividing the South into five military districts, placing a general in charge of each district. The general’s job, among others, was to register voters and ensure that former Confederates are kept out of government and to ensure that each state drafted a new constitution divorced from slavery. Johnson vetoes the bill. Congress overrode the veto. There were race riots during the election. Ex-Confederate soldiers attacked black (both ex-slaves as well as ex-Union troops) in New Orleans and Memphis killing dozens and destroying many black homes and churches. Ulysses S. Grant, who accompanied President Johnson in his whistle stop “Swing Around the Circle” speaking campaign, was disgusted by this and became more of a Radical Republican.

Congress passed the Army Appropriations Act. This Act required the president to issue any orders to Union military governors through General Grant. Then Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, which protected Secretary of State Ed Stanton from being fired by Johnson. The Act stated that presidential appointees could not be fired without seeking Congressional approval. The next year Johnson tried to dismiss Stanton. Congress reminded Johnson of the Tenure of Office Act. Johnson refused to budge, so Congress wrote up impeachment charges against Johnson (more on that below).

Congress divided the South into five military districts (Virginia, the Carolinas, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, Mississippi and Arkansas, and Louisiana and Texas). Soon thereafter, the general in charge of each district registered the new electorate, disloyal whites, approximately 20% of the voting population, were disenfranchised. Blacks would vote and would participate in drafting their state’s new constitution. New legislators would then be elected and those would be required to ratify the 14th Amendment. Congress would review the results of the elections as well as each states’ constitutions and if accepted, the new Republican House and Senate members would be recognized and thus seated.

Reconstructing the North

In January of 1867, Congress enfranchised blacks in Washington D.C, they adopted universal male suffrage in the territories and two years later the country passed the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Three years earlier, Johnson took what he called “Swing Around the Circle” to promote his ideas. At that time riots broke out and the issues with ex parte Milligan surfaced.[10]

Congress passed the Army Appropriations Act. That Act prohibited the ex-Confederate states from the Enfranchisement act from acting against the wishes of military officers unless approved by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, senior officer of the group. This led to impeachment articles against Johnson. The Tenure of Office Act prohibited the president from firing any appointment that initially needed Congressional approval to be appointed.

Johnson suspended Stanton in August of 1867. Johnson was the head of the tribunal charged with investigating the conspiracy against the led to the assassination of Lincoln, Johnson had suspended Stanton in August of 1867 because it, discovered that the tribunal investigating Lincoln; assassination suggested that one conspirator, a woman, be given leniency (Mary Surratt). Stanton did no tell Johnson, who had Surratt executed and that was when Stanton fired Johnson. A replacement for Stanton was never seated so Congressional Reconstruction continued. Trumball also sought to establish a new court system, believing that the established courts swindled blacks in the South. Without federal protection, the Freedmen will be abused and virtually re-enslaved without federal protection for the safety and welfare of “all” Americans, poor white and all black people. Johnson refused to support these measures.

All of this led to Johnson’s impeachment. Congress believed that Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act when he fired Stanton without seeking Congressional approval. But the straw that broke the camel’s back was Johnson’s approval of Mary Surrat’s execution. The House promptly impeached Johnson. The Senate then voted on the punishment. The most important charge against Johnson was “heaping ridicule upon Congress,” which was a reference to his Washington’s birthday address. Congress voted 35 to 19 to remove Johnson from office -one vote shy of doing so. 12 Democrats voted against conviction. Seven Republicans voted with the Democrats to include three Radical Republicans: Ross of Kansas, Fessendon of Maine, and Lyman Trumball. Republicans wanted to send a message to Johnson that the Republicans owned Johnson and that Johnson better play nicely with Congress. Keeping Johnson in office gave the Republicans a campaign issue in the next presidential election.

One of the most radical of the Radical Republicans was Thaddeus Stephens of Pennsylvania. He died shortly after impeachment. Before dying, he publicly supported Johnson’s assassination. On his deathbed he allegedly uttered, “I was to be the dagger of Brutus,” a suggestion that there was indeed a plot to kill Johnson. Nevertheless, President Andrew Johnson was politically disemboweled.

1868 was a presidential election. The Democrats ran Horatio Seymour, who won eight states versus the war veteran Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The Democrats ran against Reconstruction and against universal male suffrage while the Republicans supported the continuation of Reconstruction, supported black male suffrage in the South, but was very quiet on lack male suffrage in the North. Grant won. His eight years in office was riddled with scandal and fraud by those closest to Grant.

Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and Conservatives (Democrats)

It’s too easy (and incorrect) to say that those carpetbaggers took advantage of the ruinous condition of the South and the poor southerners, that scalawag were traitors to the cause and took advantage of the situation by joining the ruling party, and that Democrats were slack-jawed yokels. There’s positive and negative in any group.

Carpetbaggers (a pejorative) were northerners who came south during reconstruction. Almost always Republicans. And ostensibly to help. Scalawags (a pejorative) were southerners who became Republicans during Reconstruction, ostensibly to help rebuild their society with the help of those in power. And, Democrats were Southerners who retained their affiliation to the Democratic party before and during Reconstruction. They can too easily be viewed as people who fought against the march of modernity.

Carpetbaggers

Simon Conover was from New Jersey. He obtained a medical degree in Nashville and was a surgeon in the Union Army. He ventured to Florida during Reconstruction as a Republican. In fact, he was a delegate to Florida’s constitutional convention. Then he became a US Senator, married a wealthy Confederate widow, and eventually led the movement to disenfranchise blacks in Florida by prohibiting ex-convicts from voting. Then Florida passed those Black Codes, such as “vagrancy” which resulted in thousands of newly minted citizens from losing their right to vote. He eventually moved to Port Townsend, Washington where he resumed his medical practice and helped create an agriculture school. That ban on convicts from voting in Florida, which targeted blacks, was repealed in 2018. Simon Conover is an example of a Republican who did not use his position to help the ex-slaves in their transition to freedom.

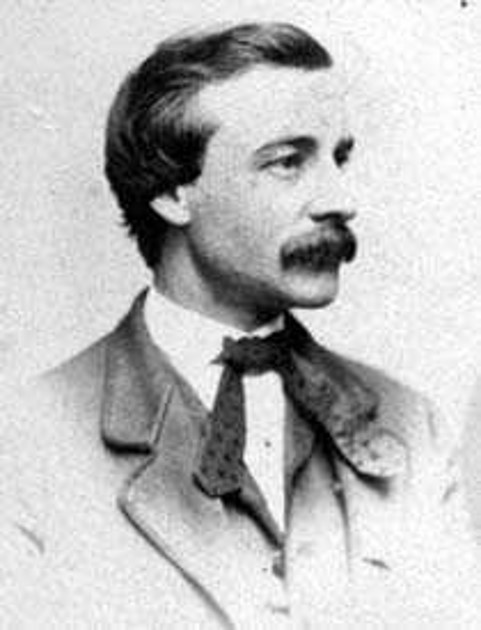

Albion Tourgee was from Ohio. He fought with the Union, was wounded twice, and became a POW. After the War he moved to North Carolina where he became a district judge and leader of the Republican party. He was central to the distribution of ex-Confederate lands to freedmen, ended property qualifications for voting, office holding and sitting on juries. He established several freedman’s school. All of which attracted the attention of the Klan. Tourgee became critical that Reconstruction leaders in North Carolina were abandoning blacks eventually left (or was chased out) North Carolina. He took up many civil rights cases to include one for a man named Homer Plessey. Plessey challenged the Louisiana law that created white and black sections of railroad cars. Tourgee took the case all the way to the Supreme Court, eventually losing. However, Tourgee was a person of integrity who used his position to further the needs and civil rights of blacks in the South.

Brianna Clifton examined two relatively unknown Carpetbaggers: D.P. Upham and Barbour Lewis.

In 1865, Daniel P. Upham, or D.P. Upham, traveled from Massachusetts to Arkansas looking for economic opportunities after his business up north failed. East Arkansas held ample opportunity to make money in the cotton industry. He had connections with military commanders who controlled the cotton trade. This allowed him to purchase interests in a saloon, a two-thousand-acre cotton plantation, as well as, a concern for trading. With Reconstruction, came the opportunity to build a political career. Upham used the black populace, who were now able to vote and made up an ample percentage of the votes in Woodruff County, Virginia, where he resided, to help him get elected into the Arkansas House of Representatives. He advocated for black rights, and he even went as far as to get the schools integrated. However, this was met with backlash from the KKK, who, naturally, wanted him killed. Unfortunately, during the presidential elections, the Klan scared black freedmen out of their vote enough to give Democrats the majority vote.[11] He ultimately saw much success, but he was not accepted very well by the native southerners.

Like Upham, Barbour Lewis held ranks as an officer for the Union Army. He also practiced law. Initially from Illinois, he settled in Memphis, Tennessee where he won positions in local and federal offices. He also considered himself a radical republican. He prided himself in being an abolitionist and protecting abolitionists alike through law. He pushed for the rights of the black populace. Just like Upham, the KKK highly opposed everything Lewis stood for and threatened and sabotaged him. Lewis even witnessed the killing of innocent freedmen as well as riots. The Democrats eventually won the state of Tennessee as well. [12]

Three things can be noted. Firstly, these two men, considered Carpetbaggers, had more financial and political success in the Southern states. Secondly, they advocated for black rights. And lastly, the Ku Klux Klan did not tolerate them well. While they did not win the Republican vote for the Southern states that they represented, they were still able to influence and spread their political ideologies throughout the South. Their brief efforts did make a difference and leave a mark in history.

Scalawags

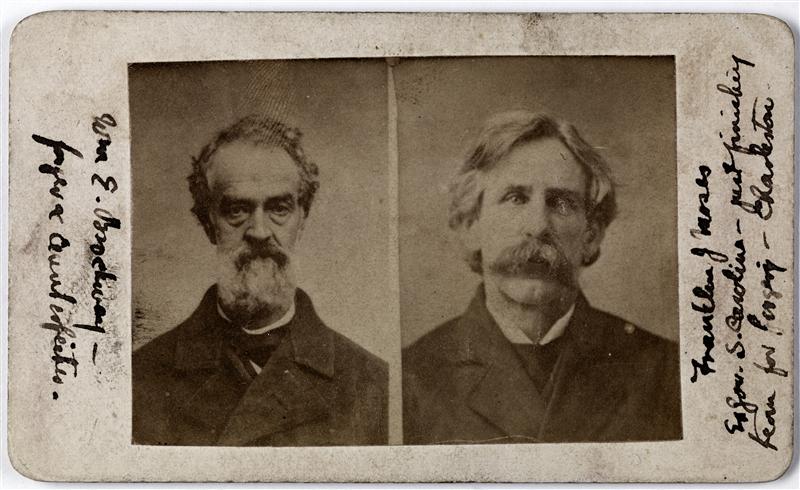

Franklin J. Moses was a well-educated fire eater from South Carolina who claimed to be the one who took down the US flag from Fort Sumter. A claim many southern men had made. But during Reconstruction he joined the Republican party and was a member of the state’s constitutional convention. He later became the state’s Speaker of the House then governor advertising that he could be bought. He did help organize a local militia ostensibly to protect black voters, but more likely to intimidate men from voting for Democrats. He was a heroin addict who died either by an accident or suicide (leak from a gas stove). 20th-century biographers focused on his personal failures (such as spending tens of thousands on living expenses and entertainment while governor, drug addiction, and numerous larceny convictions). However, recent work tends to focus on his interest, and somewhat success, in advancing civil rights for both African Americans and Jewish people of South Carolina. For example, professionally and personally he placed himself in the company of Black people, he tried to integrate the University of South Carolina, he appointed a mixed-race trustee, for example. His success in helping the freedmen of his state was limited to the Reconstruction period as once Democrats gained control of the state, they reversed all of Moses’ gains.[14]

Edward Deneger was a Texan but from Germany. Before migrating to the US he tried to instill political reform but fled to the US once the Prussians ended all hope of democratic experimentation. Before Texas voted to commit treason, Denenger launched a pro-Union newspaper, which was destroyed by the locals. Two sons were murdered by Confederates and he fled to California with the Texas Rangers nipping at his heels. During Reconstruction he returned to Texas. Helped establish the Republican party, started a newspaper, and served as a member of Congress. He ended his political career, and Reconstruction, as a member of the city council of San Antonio.

Conservatives

Peter Dox was an Alabama planter, owned 26 slaves, and a Confederate officer. He was a Congressman from Alabama and a constant critic of President Grant, his policies and Radical Republicans. But one day he married one of those Carpet Baggers who convinced him that they had an obligation to assist Freedman through education. He established a black school, where his wife taught. The KKK was not happy with this, so they burned the school down. Dox rebuilt and the Klan burned it down. Eventually, Dox ambushed and killed 8 Klan members clearly demonstrating that he had on obligation to help Blacks in their transformation from slavery to freedom. However, another source states that Dox was against educating the ex-slaves.[15]

William Hemmingway was a large slaveholder from Mississippi and a Confederate officer during the War. After the War he became a state legislature who authored the 1875 plan to use force and violence to end Reconstruction. As State Treasure he embezzled around $300,000. At his trial, his defense was that he was to use the money to buy weapons to arm those who would use violence to push the Republicans out of Mississippi. He was sentenced to five years but never served any jail time.

Freedmen

Robert DeLarge was born free in South Carolina. Hos family owned slaves and Robert worked for the Confederate Navy during the War. During Reconstruction was an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau. A member of the South Carolina Land Commission and a US Congressman. While a supporter of Republican legislation coming out of the governor’s office, he did try to maintain some assemblance of autonomy. “I am free to admit,” De Large noted on the House Floor while advocating for victims of racial violence in the South, “that neither the Republicans of my State nor the Democrats of that State can shake their garments and say that they had no hand in bringing about this condition of affairs.”[16]

He helped develop the Republican Party in South Carolina and sat on the state’s constitution convention. Apparently, he was both wealthy and conservative. “He advocated mandatory literacy testing for voters but opposed compulsory education while supporting state–funded and integrated schools. He did favor some more radical measures, however, arguing that the government should penalize ex–Confederates by retaining their property and disfranchising them.”[17]

Some argue that the SCLC failed in some measure because of DeLarge’s corruption. DeLarge bought the land then sold it back to SCLC for a tidy profit he supposedly also skimmed money off the sale of lands in order to fund his political campaigns. However, he was never charged for any crime.[18] Nevertheless, instead of using his position to help the freed slaves, he used his position to enrich himself.[19]

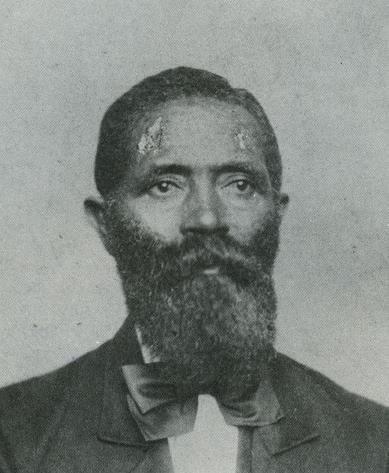

George Teamoh was born into slavery and worked in the shipyards of Norfolk, Virginia. One time he was leased to a German company and on the return trip he jumped ship in New York and declared himself free. He settled in Massachusetts in 1853. After the War, Teamoh returned to Virginia to search for his family. He found his wife and then-grown daughter both decimated by an abusive master. Teamoh entered Virginia politics as a Republican. He unsuccessfully tried to make it illegal to whip both black and white people but was successful in helping to create the eight-hour workday for federal employees. Eventually he lost his house and like many Blacks, lost whatever gains and civil rights they experienced during Reconstruction when the Redeemers took control of the state at the end of Reconstruction Teamoh wrote his autobiography and did not appear in the public records after 1887.[20]

Then there was the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees, and Abandoned Lands. Usually known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress in order to deal with the massive crisis of dealing with around 4 million people in need of food, shelter, and medical treatment. The Bureau also constructed schools and provided other down-range assistance. But how successful was the Bureau? Joseph Enriquez looked at this question.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was passed by Congress on March 3, 1865 with the goal of assisting newly freed slaves within the year following the civil war.[21] This would be done through financial, medical and educational help to help transition them into normal society. Examples of their assistance would be through getting loans for freed slaves and also opening schools like Howard University. This is important, as one year is not nearly enough time to fix centuries of racism, slavery, and abuse that newly freed slaves had experienced. After losing the war, the south was still filled with racist ideologies and a community of white supremacists.

For example, securing the rights within the justice system for freed slaves proved difficult. General Wager Swayne was appointed assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau for Alabama, where both sides of the issue were unhappy, with whites uncertain of their future and blacks uncertain where to begin their lives. Within Alabama, he attempted to implement regulations for the courts to be open to the Negroes the same as the whites; however, even with new rules, the existing racist magistrates upholding the courts abused their power to undermine justice.[22]

The failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau to enforce justice for the Negroes showcases how ineffective it was at helping many in need. The temporary enactment of the Bureau also created a large weakness, as changes attempting to be implemented would ultimately dissolve along with the Bureau.

On top of this, the reclaimed land from Confederate owners to be distributed to the Negroes would eventually be returned to them through an oath to the US. This left many freedmen stuck without income and the Bureau deprived of revenue.[23] With barely anything to offer to Africans and also a lack of consistent financial support, it was difficult to make lasting change within the south.

Some freedmen would resort to going back to their masters, whereas others who would attempt it would end up punished. Jourdon Anderson moved to Ohio from Tennessee following the emancipation. His former master, Colonel P.H. Anderson eventually messaged him asking to come back. Jourdon’s main concern was the safety of his family, as he was shot twice by him before leaving and also was threatened to be shot by a neighbor next time they saw him.[24] Again, the Bureau failed to protect Blacks, forcing some into unsafe working environments, and lacking the power to help them. Within many state governments, race issues were not a priority, leaving many to fight for their own rights.

The aftermath of the Civil War left America in a place of division and distaste amongst its population. The Freedmen’s Bureau was enacted to assist freed slaves with transitioning into society but instead lacked the resources and support to make a lasting change in the South.

Well, this is just the proverbial tip of Reconstruction’s iceberg. Just a few thoughts that I find of importance/interest. Eric Foner provides the first and last word on this period of US history so check out his works, including Foner’s most recent book, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution. In the next chapter, we look at the Civil War and Reconstruction out West, an area that I think may be overlooked in traditional US history textbooks (and lectures in those survey courses including my own at times).

I would like to thank Brianna Clifton and Joseph Enriquez for their interest in Reconstruction. Their essays added value to this chapter.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies. Please point out any inaccuracies to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Said by an ex-Mississippi slave in Give Me Liberty! Seagull edition, 2006. Eric Foner, p. 479. ↵

- https://www.splcenter.org/unite-the-right ↵

- https://catholicism.org/priest-poet-patriot-father-abram-j-ryan.html ↵

- https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/lincoln-issues-proclamation-of-amnesty-and-reconstruction ↵

- https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln7/1:191?rgn=div1;view=fulltext ↵

- https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln7/1:191?rgn=div1;view=fulltext ↵

- https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/letter-to-governor-michael-hahn/ ↵

- https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau ↵

- http://web.mit.edu/21h.102/www/Primary%20source%20collections/Reconstruction/Black%20codes.htm ↵

- https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_exparte.html ↵

- Charles J. Rector, “D.P. Upham, Woodruff County Carpetbagger” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 59, No. 1, (Spring, 2000): 60-67, JSTOR. ↵

- Walter J Fraser, Jr., “Barbour Lewis: A Carpetbagger Reconsidered”, Tennessee Historical Quarterly Vol. 32, No. 2, (Summer, 1973): 148-157, JSTOR. ↵

- From Rogue's Gallery, Brockway -- forger [Wm. E. Brockway] and [Franklin J.] Moses -- Ex Gov. of South Carolina. ca. 1890 ↵

- For example, see http://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/moses-franklin-j-jr/ ↵

- encyclopediaofalabama.org ↵

- Congressional Globe, Appendix, 42nd Cong., 1st sess. (6 April 1871): A230. ↵

- https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/12090 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Dr. Richard Hume, "Reconstruction in the South, April 20th, 1999, Washington State University. ↵

- For more information on George Teamoh see Teamoh, George. God Made Man Man Made the Slave: The Autobiography of George Teamoh, edited by F.N. Boney, Richard L. Hume and Rafia Zafar (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1990) ↵

- “Freedmen's Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866,” U.S. Senate: Freedmen's Bureau Acts of 1865 and 1866, January 12, 2017, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/FreedmensBureau.htm. ↵

- Bethel, Elizabeth. “The Freedmen’s Bureau in Alabama.” The Journal of Southern History 14, no. 1 (1948): 49–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2197710. ↵

- Alderson, William T. “THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU AND NEGRO EDUCATION IN VIRGINIA.” The North Carolina Historical Review 29, no. 1 (1952): 64–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23515643. ↵

- Anderson, Jourdon, “A Letter “To My Old Master,” in American Perspectives: Readings in American History, ed. HCC C College, vol. 1 (McGraw-Hill Learning Solutions, n.d.), 618. ↵