30 The Good War at Home

WWII

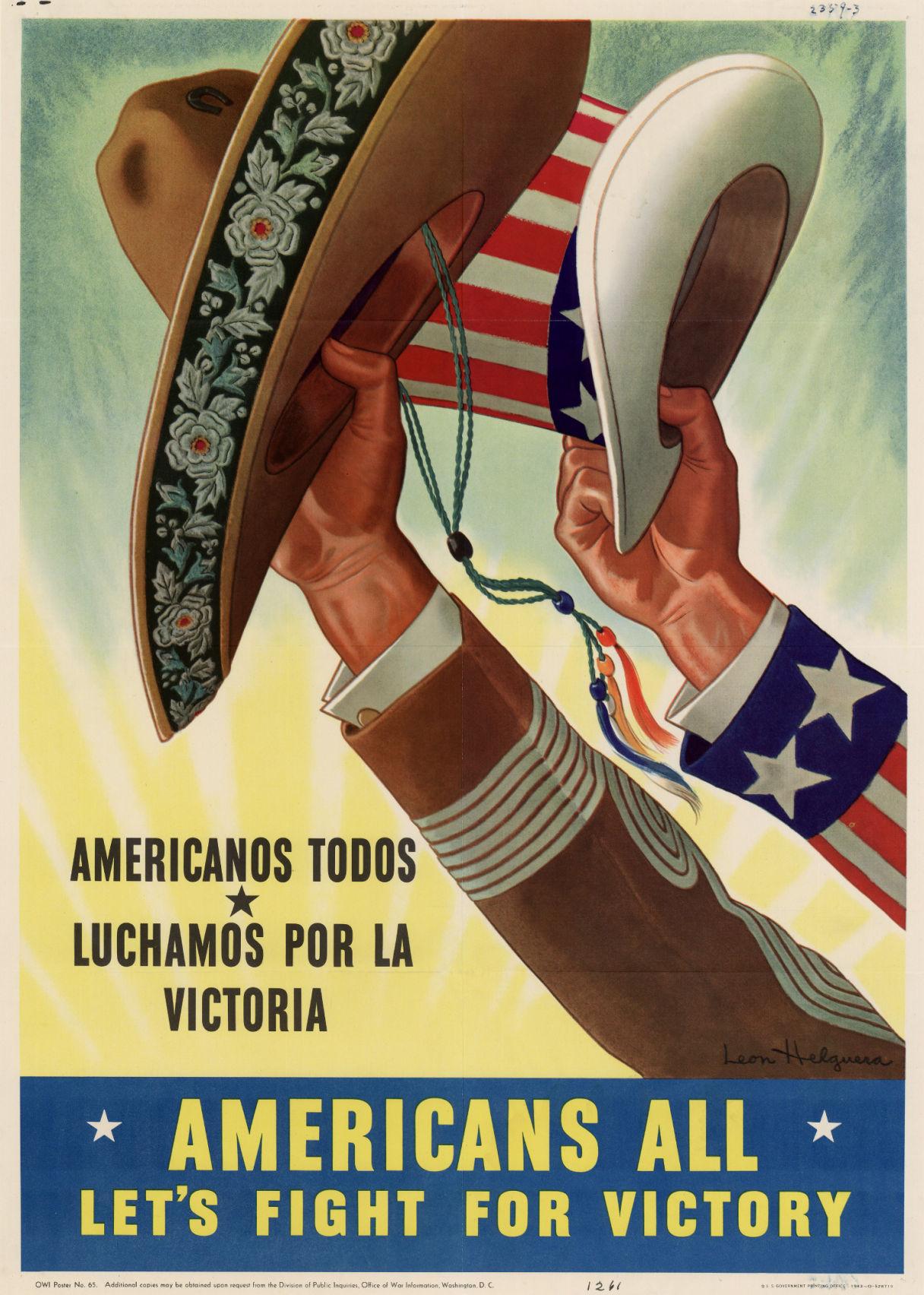

This chapter focuses on the histories of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals residing in the US, and women. Three groups that were wildly affected by World War II. While Mexicans were given economic opportunities, Mexican Americans were treated as second-class citizens; they were not seen as fully patriotic and thus open to be abused. People of Japanese descent (regardless if they were born here or retained legal connections to Japan) lost the most during the War. They lost everything: their homes, their possessions, and their liberty. The Fifth Amendment seemed not to apply to those people. And, like wars and national emergencies of the past, World War II offered new, exciting, dangerous, and sometimes deadly opportunities and experiences for women. Also, the war was reflected in some of the popular comics and cartoons of the day. Finally, although Italy was part of the Axis, the US government used Italian nationals and Italian Americans (to include some in prison) to provide intelligence and security at some of the more important ports or docks along the Eastern seaboard.

One hallmark of the New Deal home front was new workers: approximately 200,000 Mexicans, 75,000 Native Americans left their reservations and 1 million more African Americans found new opportunities in war-related factories (a total of around 3.8 million African Americans) while around 1.2 million rural African Americans migrated to the north to seeking factory jobs. The number of women in the workforce doubled to around 19.5 million and one-third of all ship builders in California and plane builders in the Seattle area were women.

Marriages increased during the War. According to the US Census Bureau, about 1 million women reported that they would not have gotten married had it not been for the War. Divorces also hit new records. The War at home also impacted civil rights. Executive Order 8802 (1941) barred segregation/discrimination at defense plants. Major race riots and strikes took place in war factories and ports throughout the country; seemingly wherever there were attempts to enforce EO 8802.

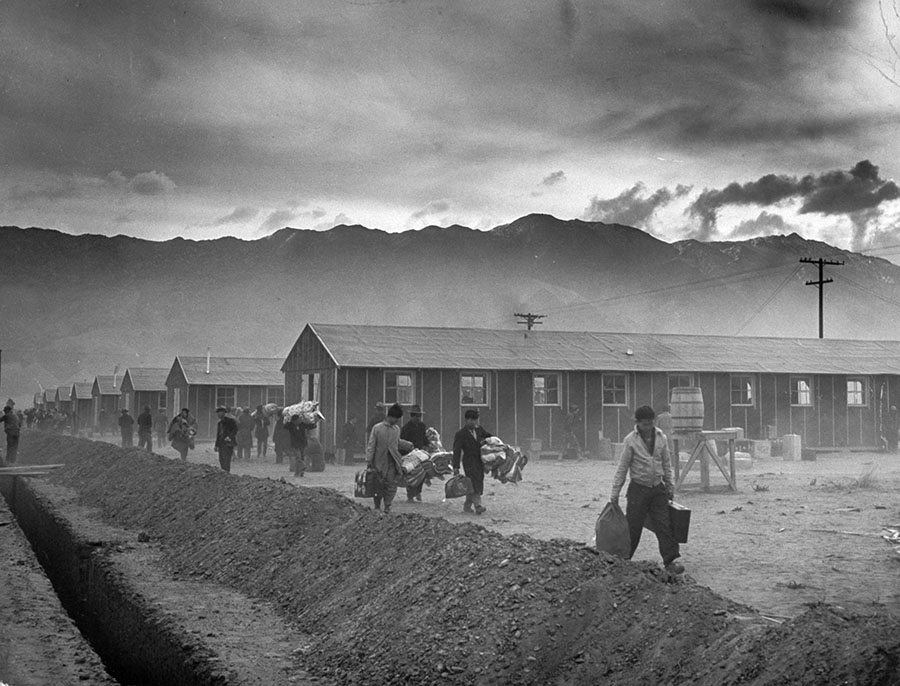

The day after Imperial Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor in the Territory of Hawaii, the US froze all US-Japanese funds. Executive Order 9066 (19 FEB 42) called to remove Japanese-Americans from the West coast. Overall about 120,00 people were kept in internment camps, of which the US Supreme Court upheld the Constitutionality. They lost billions and billions in homes and businesses as they could not pay their mortgages and some of their properties were simply taken by local communities. In 1988, the US government issued a formal apology and gave $20,000 to each of the 60,000 or so survivors. About a total of $1.2 billion in 1988 or $1.7 million in 1942.

The US-Mexican border had been fluid for most of US history. The US Border Patrol was not formed until 1924. And even after that a regular occurrence were Mexicans working in the US and Americans owning factories in Mexico, with both groups traversing the border daily without interference. The Great Depression resulted in the Mexican Repatriation in which Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported to Mexico. Because of the war, and with so many Americans working in war-related industries, there was a need for agricultural workers. So, in 1942 the US and Mexico announced the Bracero program (aka Mexican Farm Labor Program Agreement): an opportunity for Mexican workers to enter the US to work in the agricultural fields such as those in the Texas Rio Grande Valley, California’s Central Valley, the Willamette Valley in Oregon, and the Wenatchee Valley in Washington. Under the auspices of the Department of Agriculture, the Bracero program was supposed to be a temporary measure to meet the immediate needs of the war. The program continued until 1964, well past the war and any food emergency,

In 1943, just one year after the program was launched, growers in Texas, with the help of the American Farm Bureau Federation asked the US government to alter the terms of the agreement so Texas farmers could directly bring in workers from Mexico. Those workers would be considered to have entered the country “illegally.”[1] The program allowed for 200,000 legal workers but the number of “illegal” workers is unknown.

Mexican braceros (who came from agricultural regions of Mexico such as “la Comarca Lagunera” and Coahuila) entered the US through official ports such as El Paso, Texas.[2] When braceros entered they signed contracts with their American employers. The contracts were in English and not under the control or supervision of the US government. According to one source, the braceros did not necessarily understand their rights and conditions of employment, such as how much they would make per hour, how much they would have to pay for rent and food.[3]

Los Angeles had a gang problem in the 1940s. Gangs were arranged along racial or ethnic lines and violence tended to be intra-racial rather than inter-racial. In other words, multiple gangs existed from neighborhoods in which the ethnic or racial makeup was homogeneous. Mexican American neighborhoods had several Mexican American gangs, for example. Sleepy Lagoon was an irrigation reservoir in rural Los Angeles. Kids used the area for swimming during the day, and couples were attracted to the relative quiet and unlit scene.

Three days before the Bracero Program was announced, Hank Leyvas and his extra-special friend Dora Barrios were parked along Sleepy Lagoon. They were part of a group of couples from the 38th street neighborhood of Los Angeles who came that night to the reservoir. They were probably gang members. Certainly Frank was characterized as someone who ‘was feared and respected by many.” They were then attacked by “a group of boys from a rival neighborhood.” The attackers beat Leyvas and Barrios “mercilessly.”[4]

Leyvas was able to make it back to his turf, gathered “reinforcements” (around 30) and headed back to Sleepy Lagoon. By the time that the Leyvas-headed detachment made it back to the reservoir, the place was a ghost town. Empty. Still. Quiet. However, they could hear the sounds of people laughing and music coming from the nearby Williams Ranch. Sleepy Lagoon was used to irrigate the ranch. Leyvas concluded that the group who assaulted him was at that party. Leyvas and his group fell upon the party-goers. “The fighting was brutal.” The only person who died that night was Jos Diaz. Diaz was born in Mexico but grew up in the US, and was attending a birthday party, not a party hosted or attended by the boys who earlier attacked Leyvas and Barrios. Diaz was also celebrating his final days of freedom as he was shortly going to enter the Army and report to Basic Training.[5]

The governor of California, Cuthbert Olson (D), used this murder as a pretext to round up suspected gang members. But in the net were caught innocent Mexican Americans. Around 600 young people were arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department.[6] Every generation has characteristics that define one generation from another to include music, language (slang), and even clothes, Think Forever 21. Clothes at Forever 21 are not designed for the mother who goes shopping with her teenage daughter, for example. Just like a high school teen would probably not buy her clothes at Talbots or White House Black Market.

Anyhow, one characteristic of young men, not necessarily Mexican American men, was the Zoot Suit. A Zoot Suit, as the image above shows, is a baggy or loose fitting suit. Wide shoulders and lapels. Broadly cut under the arms and waist with very long sides. The pants balloon a bit towards the knees then tighten to the upward cuffed ankles. The shirts have wide, long collars. Look at the photo above. Looks like either an NCO club, an Army mixer, or a dance for enlisted men. Look at the woman on the right side. Look where she is looking. She is checking him out! I cannot tell if she likes the suit or not, however. My wife, also a historian, thinks the woman does not like what she sees.

Many saw the Zoot Suit as unpatriotic. Compare the Zoot Suit with how the soldier is dressed. His uniform is what contemporarily is known as a “Slim” or “Fitted” style. The uniform is cut higher up under the armpits, sleeves stop at the wrists, there is no break in the pants which are straight. None of the soldiers are wearing their jackets, but if you saw one you would notice that the jackets at that time fell to the waist. In other words, because of material conservation due to the War, the Zoot Suit was looked upon by the older generation, especially white Americans when Mexican Americans were sporting the clothes, as un-American, un-patriotic.

Hank Leyvas and others were indicted for the murder of Jose Diaz. They were found guilty in the press. Then the jury agreed. Leyvas was sentenced to life in San Quentin prison. He and all of the boys imprisoned for the murder will be released within a year as their conviction will be overturned on appeal due to racism, bias, and other issues such as a lack of evidence. Shortly after the conviction of Leyvas, et al, American service members descended on East LA and began beating Mexican Americans and destroying Mexican American property. Pulling them out of movie theaters, restaurants, and other public venues. Mexican American youth tried to defend their neighborhood and themselves. For the most part the police did not intervene on the side of Mexican Americans.[8] The riot came to an end in part when President Roosevelt ordered the servicemen back to their bases because the Japanese government was using the riot for propaganda purposes.

After the War, the Bracero program continued. In 1949 there were 280,000 legal Mexican immigrants; 865,000 by 1953. Then fear and anxiety gripped Americans by 1954 (see next chapter) and there might have been over 1 million Mexican agricultural workers in the US at a time when the economy began to sink. So in 1954 the US government in cooperation with the border states, launched Operation Wetback. Rounding up Mexican legal and illegal Mexican agricultural workers, as well as Mexican Americans (as was the case during the Great Depression), and deported them to Mexico.

About 500,000 Mexican Americans fought in World War II.[9] One of them was Marcario Garcia. Garcia was born in the Mexican state of Coahuila in 1920. He spent a good part of his life in Sugarland, Texas. He was a cotton farmer when the war broke out and in November of 1942, Garcia enlisted in the US Army. He was assigned to Company B, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. He was part of the Normandy invasion. Later on, heavy fighting in Germany pinned his squad down. Garcia took the initiative to charge German emplacements. Once the smoke cleared, he saved his men, took four German prisoners, and was wounded himself. This Mexican American was awarded the nation’s highest military distinction, the Medal of Honor. Here is how the citation is read:

“Staff Sergeant Marcario García, Company B, 22nd Infantry, in action involving actual conflict with the enemy in the vicinity of Grosshau, Germany, 27 November 1944. While an acting squad leader, he single-handedly assaulted two enemy machine gun emplacements. Attacking prepared positions on a wooded hill, which could be approached only through meager cover. His company was pinned down by intense machine-gun fire and subjected to a concentrated artillery and mortar barrage. Although painfully wounded, he refused to be evacuated and on his own initiative crawled forward alone until he reached a position near an enemy emplacement. Hurling grenades, he boldly assaulted the position, destroyed the gun, and with his rifle killed three of the enemy who attempted to escape. When he rejoined his company, a second machine-gun opened fire and again the intrepid soldier went forward, utterly disregarding his own safety. He stormed the position and destroyed the gun, killed three more Germans, and captured four prisoners. He fought on with his unit until the objective was taken and only then did he permit himself to be removed for medical care. S/Sgt. (then Pvt.) Garcia’s conspicuous heroism, his inspiring, courageous conduct, and his complete disregard for his personal safety wiped out two enemy emplacements and enabled his company to advance and secure its objective.”[10]

Japanese Americans

As US-Japanese relations deteriorated throughout 1941, and before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt ordered an intelligence gathering operation against Japanese Americans in California in order to ascertain their loyalty.[11] This investigation was led by Curtis B. Munson of the State Department.

People who immigrated to the US from Japan (the Issei) Munson reported, “send their boys off to the Army with pride and tears. They are good neighbors.”[12] Those who were born here (the Nisei) and “are not Japanese in culture. They are foreigners to Japan. Though American citizens they are not accepted by Americans, largely because they look differently and can be easily recognized. The Japanese American Citizens League should be encouraged, the while an eye is kept open, to see that Tokio does not get its finger in this pie — which it has in a few cases attempted to do. The loyal Nisei hardly knows where to turn. Some gesture of protection or wholehearted acceptance of this group would go a long way to swinging them away from any last romantic hankering after old Japan. They are not oriental or mysterious, they are very American and are of a proud, self-respecting race suffering from a little inferiority complex and a lack of contact with the white boys they went to school with. They are eager for this contact and to work alongside them.”[13]

Munson examined other divisions within Japanese/Japanese-American identities but overall he concluded that there was little to be concerned about:

And in fact concluded the opposite of what was going to happen to Japanese-Americans:

On February 19th, 1942, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which instructed all Japanese and Japanese Americans to be removed from the West coast to internment camps elsewhere. Former Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark who represented the Department of Justice in the relocation of hundreds of thousands of people wrote:

What follows are essays on the Manzanar and Gila River interment camps, researched and written by my students. These essays are important because the student-historians came across evidence that has been relatively unknown or has not seen the light of day in quite a while. By blowing the dust off those sources they shed new light on a well known aspect of US history.

The first essay examines ways Japanese American children attempted to keep their Japanese culture alive in the Manzanar Internment camp, in California, during WWII through the eyes of Jeanne Wakatsuki, Houston.[17]

After the attack of the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, there was a lot of fear about future attacks on the U.S. with help of Japanese Americans that lived on the West coast. Although most of the Japanese that lived near the West coast were American citizens; there where many laws in place that did not recognize their citizenship and as a result, they were treated like second class citizens. This can be seen by the Alien Land Act of 1913, that prohibited ownership of land along with leasing and sharecropping. The law stated that ineligible aliens for citizens could not own land, since these Japanese Americans where not considered white, it was implied that Asians could not become citizens. This was later legitimized when in 1921 Takao Ozawa was denied citizenship by the Supreme Court.[18]

The fear that anyone of Japanese descent might ally with the Japanese government and be a threat to the U.S. lead to President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066.[19] This caused most people of Japanese ethnicity to be moved from the West coast and into camps designed to keep all Japanese people away from big populated centers and prevent Japanese Americans from potentially participating in any attack like the one in Pearl Harbor. One of these Japanese Americans was Jeanne Wakatsuki, a 7-year-old that was forced along with her family to move from their home in Los Angeles to the Marzanar internment camp located near the Nevada border. About 70% percent of the Japanese that ended up in the camps were Nisei (second generation, children of Issei) and 30% Issie (first generation, born in Japan and immigrated to U.S. between 1890 and 1915).[20] Most of these Nisei where more American than Japanese. There where some underlying traditions of Japanese culture in most of the Nisei and Issei like big family meals and some basic Japanese words but for the most part their knowledge of Japanese culture had been watered down. Wakatsuki like most Nisei didn’t speak Japanese only English and didn’t even understand most Japanese traditions. Aspects of traditional Japanese culture were lost from the Issei to the Nisei. This can be seen in the fact that Wakatsuki’s family kept a Buddhist shrine, yet they never prayed, nor had she even been inside a Buddhist church.[21]

Wakatsuki along with all the Japanese would be told an old Japanese saying “Shikata ga nai” (it cannot be helped). Although it was just a saying all the Issei would tell the children and each other it became a saying that united them. This was a part of the Japanese culture that seem to affect all the generations alike, the Nisei, the Issei and of course the Japanese immigrants. This can be seen by the way everyone in the camp would react. Everyone in the camp had a hard time adjusting when they found out their living conditions in the camp. It included sleeping on the floor, thin blankets, dust and cold air coming through holes in doors and no privacy to use the restroom. As humiliating as the conditions on the camp were, Wakatsuki and all the Nisei would be told by the Issie, “Shikata ga nai”, and by just hearing that everyone knew, they just had to endure it. A simple saying but with a heavy meaning to both the Japanese and Japanese Americans alike. Both generations became a united group with this saying. (“Shikata ga nai”)

Wakatsuki had a very had time to get used to the bathroom situation as well as all the Japanese woman in the camp. Japanese culture is humble, formal, and very polite.[22] Honor is a crucial part of the Japanese culture. No partitions in the restrooms was beyond embarrassing and difficult for the modest people. Their small solution was to use cardboard to make some sort of partition. The cardboard used for this became communal and it would be passed from person to person. One person would pass it to another as they left, always saying “arigato gozaimasu” (Thank you very much). Wakatsuki’s mother ingrained that in her, being grateful and polite to the people around them, as this was part of being Japanese.

Although Wakatsuki had to spend a big part of their childhood in the Marzanar Camp she managed to keep some aspects of her Japanese culture. It was difficult because of the living conditions to be able to express the little Japanese culture she had in her as a Nisei but Wakatsuki along with the Nisei in the Marzanar camp managed to keep very important aspects of their Japanese culture with help from the Issie. Some of these included the respect and the importance of enduring hard times together (“Shikata ga nai”) that the Japanese culture teaches. Although the Nisei were Japanese American thanks to the teachings of the Issei they managed to keep their Japanese part of their Japanese-American culture.

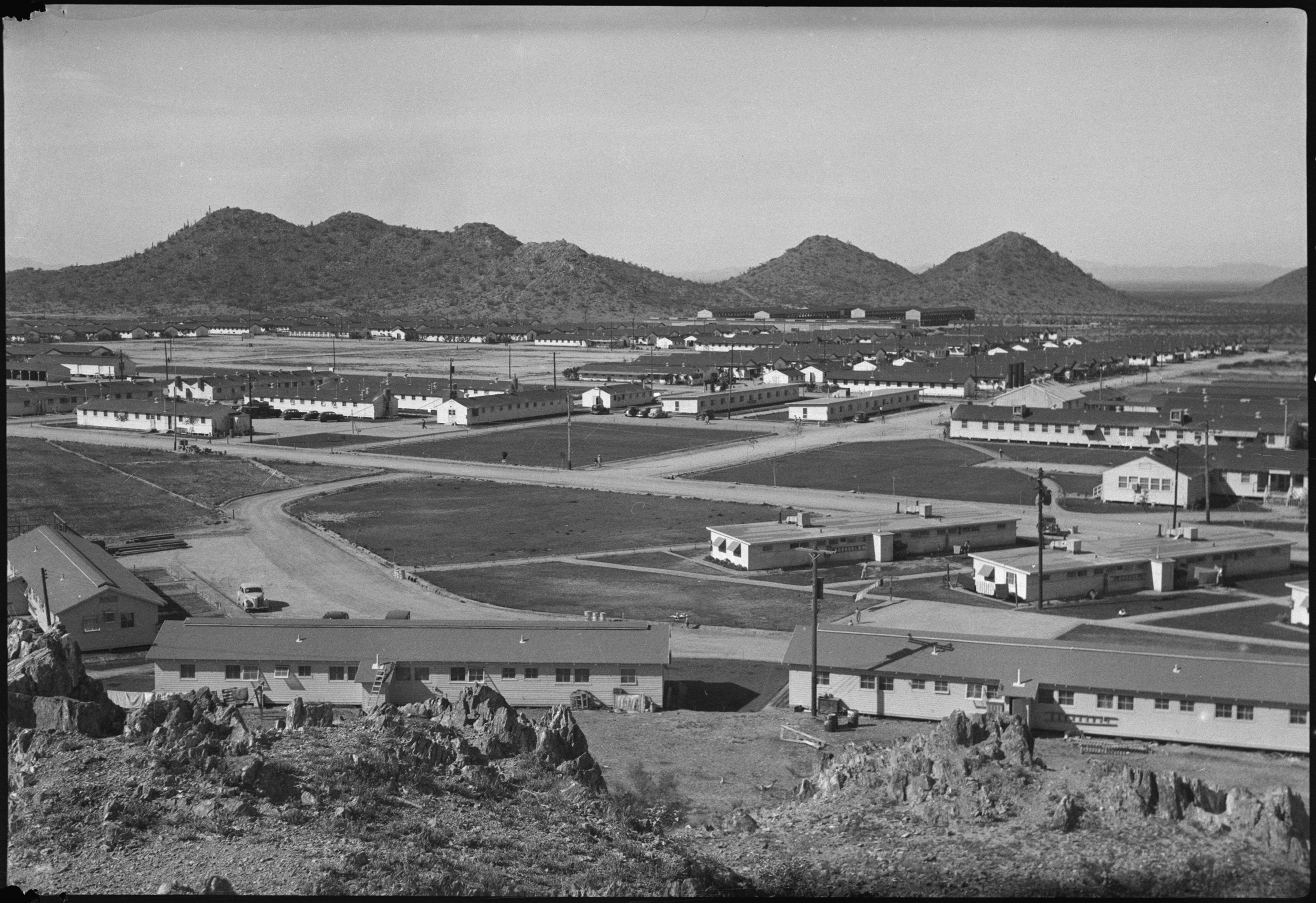

Leonel Lizalde, Alejandra Lopez, Tatyana Marquez, Damian Mendez, & Paulina Mosqueda researched and wrote this essay on the Gila River Relocation Center, in Arizona, how the average Japanese American lived within this camp, and how it affected Mikiso Hane; a Japanese American man who wrote about his experience within internment camps. Gila River, as well as the other nine camps scattered across the United States, were significant to history because it provided new lifestyles for Japanese Americans when they were not accepted in American society during World War II.[23]

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Americans began to have a very different idea of what Japanese people were and how they live. News and government propaganda helped greatly in this way of thinking, offering more opportunity for discrimination and injustice in America. For example, many American posters and media used monsters and evil archetypes to represent the Japanese effort in the war. Just two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, leading to the internment of thousands of Japanese-Americans and other foreigners that came from Axis power countries.[24] There were several internment camps set up throughout the states, most of them located in the more western states of the U.S. such as California, Colorado, and most notably Arizona.

Out of all the relocation centers, The Gila River relocation center in Arizona seemed to be the calmest out of the other nine. It had only one watchtower, so the center did not have much security and within a few months, the barbed wire fences were removed. The people that ran this relocation center were sympathetic towards the Japanese Americans for what was happening to them, so they were extremely lenient with the treatment of the Japanese Americans.[25] They had access to the city of Phoenix, Arizona which was about 50 miles south of the city. They also had recreational activities in the desert. When the camp opened on July 20, 1942, Japanese Americans came pouring in from the Sacramento delta area, the Fresno county, and the Los Angeles area. The peak of population hit in December at 13,348. Though the center was 16,000 acres wide it was split up into two different centers with a maximum population of 10,000 people. Its reputation for being a calm relocation center even had a paid visit by the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[26] She published what she saw on the Collier’s Magazine. She writes “To undo a mistake is always harder than not to create one originally but we seldom have the foresight. Therefore we have no choice but to try to correct our past mistakes and I hope that the recommendations of the staff of the War Relocation Authority, who have come to know individually most of the Japanese Americans in these various camps, will be accepted.”

Mikiso Hane and his family were among those forced to live in one of the nine relocation centers run by a civilian agency. In his journal article, “Wartime Internment”, Hane describes the discrimination and false portrayal Japanese-Americans received while also depicting what his experience at these internment camps was like. “We arrived late at night but it was still oppressively hot. We trudged through the ankle-deep sand, headed to the empty barracks with our mattresses (straw-filled cloth sacks), and tried to sleep, wondering what was in store for us. For the next several months we struggled with the heat, the sandstorms, the scorpions, the rattlesnakes, the confusion, the overcrowded barracks, and the lack of privacy.”[27] The relocation of the Japanese-Americans was clearly a matter of racial and political grounds since it was not the first time Japanese-Americans received retaliation from the United States. “…So far as life in camp was concerned, for me it was merely a matter of inconvenience, time lost, and discomfort, and of course the humiliation and indignity that we experienced.”[28] Hane lived as a peasant boy in Japan so for him life at camp was familiar but he described the hardships others around him were facing. There were those who worked day and night at the disposal of primitive facilities. He observed how the doctors at a crowded hospital ward would work tirelessly taking care of patients and only get paid a couple dollars a month. “So far as political controversies in Poston were concerned, things were relatively calm compared to other camps like Manzanar, Tule Lake, and Heart Mountain. Michi Weglyn in Years of Infamy writes that Tule Lake was the closest thing to a Nazi concentration camp, with tanks patrolling the place and “trouble-makers” forced to renounce their citizenship at gun point.”[29] Even though the life they led at the relocation camp was distasteful, Hane believes it could have been worse for him. Unlike others who were threatened at gunpoint and forced to leave their homes completely after the dismissal of the camps, Hane received positive results and was grateful to have paid retaliation at the Poston Relocation Center.

Despite being called voluntary relocation, Japanese-Americans were inherently forced to either relocate or risk being punished with one year in prison and a $5,000 fine for violating Executive Order 9066. Those that were subsequently put in internment camps, forever lost their homes, their businesses and any other possessions not taken with them. Without their property or their livelihoods, Japanese-Americans struggled to rebuild their lives once the war ended and restrictions were lifted. Congress eventually acknowledged the injustice the United States Government inflicted to Japanese-Americans during World War II in 1988 with Public Law 100-383 – providing a $20,000 payment to those interned. “If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

38 women pilots died during World War II. Their next of kin received $250. If those deaths were male pilots, the next of kin would have received $10,000. What was the difference? Those women belonged to an auxiliary to the Army Air Corps, the Women’s Air Force Service Pilots (WASPS). For example, Margaret Sanford Oldenburg died in a training accident in Houston Texas on March 7th, 1943.[30] In 2009, Congress will recognize the work and sacrifices of these women, and bestowed the Congressional Gold Medal to the WASPS.[31] One veteran was Millicent Young. “She spent about a year at a female-only air base in Sweetwater, Texas, mainly flying an AT-6 Texan single-engine plane towing a target so male pilots could train for in-air combat.”[32] Male pilots fired live ammunition at that target. Think of the nerves of steel Young, and others, must have had, to be allowed to be shot at in order to help those male fighter pilots train to go to war. Young died in 2019 at the age of 96.

The brainchild of the WASPS was a socialite who earned her pilot’s license at an age when most of us are trying to get our first driver’s license, named Nancy Harkness Love. I was disappointed when I found out that Love Field in Dallas was not named after her. I thought for sure it was. It wasn’t. Love field is named after a long distance relative of her husband, Moss Lee Love.

Nancy Harkness Love[33]

Nancy Harkness Love was an innovative, trailblazing, pioneer, and inspiration for not only women of all ages but anyone who has been faced with adversity in their life. Obtaining her limited commercial license at 18 and her transport license at 19 really allowing for her passion of aviation shine.[34] Love would go on to marry Robert “Bob” Love, who would later become the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Ferry Command.[35] After enjoying being married, opening a company with her husband, and becoming a successful test pilot she would go on to leave her mark on history as we know it today.[36]

The war began and Love had decided she would rise to the occasion and help the country. This help came in the for of a roster of 49 highly skilled female pilots, who had each amassed over 1000 flight hours each, to whom she wrote to Lt. Col. Robert Olds about in order to start a transportation group with.[37] The then commanding general of the US Armed Forces, Gen. Hap Arnold would turn down Love’s proposal for her ferrying group, but all hope was not lost, because soon thereafter Col. William Tunner, who was the commander of the Domestic Division, would ask her to write a new proposal to initiate a new ferrying division of women.[38] A few months later the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) was created with Love becoming the commanding officer of the squadron of 29 female pilots, and after just another six months she was in command of four different squadrons each being constantly supplied with new pilots through the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD).[39] The WAFS and the WFTD would merge in August of 1943 and form the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). The WASP group would be short lived, disbanding the following year but Love was far from finished.

Love’s familiarization with aircraft and years of experience made her a valued troubleshooter within the ATC so they tasked her with verifying the efficiency of the China-Burma-India (CBI) supply route.[40] General Tunner’s “Hump Operation” was flying planes over the Himalayan mountain range and through Burma’s jungles into China and Love was to ride in these aircraft to write a very detailed report on procedural issues and efficiency along the way. Once again Love would make sure her name was remembered in history by flying “The Hump” on 08 January 1945, though having no official military flight status.[41] Continuing her legacy after he flight over “The Hump” she flew more flights on the routes boarding India and ensuring their efficiency.

On 09 February 1945 Nancy Harkness Love would conclude her duty with Ferrying Division, ATC, USAAF, leaving behind a wake of impressive feats and lasting inspiration for those who would come after her. She not only organized the WAFS after being denied by some people in powerful positions but also became commanding officer of the squadron and eventually three others. She was the first female pilot behind the proverbial wheel of P-51 Mustang but also the first to fly “The Hump”. Her resume was awe inspiring with a total of 1,685 hours, civilian and military flying combined she made sure to leave behind an undeniable legacy and mark in history.[42]

Another visionary leader during World War II was Oveta Culp Hobby. For years I thought (hoped) that Hobby Airport in Houston was named after her. Nope. The airport is named after her husband, a governor of Texas.

Oveta Culp Hobby[43]

Oveta Culp Hobby served as the head of the Women’s Interest Section for the War Department Bureau of Public Relations during WWII.[44] Hobby’s role was to find ways for women to serve for the United States, which she did by the time the war started. In May 1942, Congress passed a bill that created (WAAC), an armed corps for women to serve during the war. She had to create their own uniforms and draft up barrack plans on ways to fight during the war. Oveta Hobby was elected the first director of the (WAAC), then the title of colonel when the corps integrated into the army in 1943.The Women’s Armed Corps (WAC), was converted to an active unit of the United States Army but they served non-combat positions.[45] This is important because Oveta started the first efforts in helping women moved into having opportunities like men. During the 1940’s women’s roles changed going into World War II, Oveta helped 150,000 serve in the armed corps as more than being typical nurses during the war. [46]

In January 1945, Hobby became the first woman in the army to be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her service with the Women’s Army Corps.[47] The award was the highest non-combat award given during the 1940’s, this summaries Hobby’s outstanding efforts for women during World War II. This achievement is important because Oveta made her mark known as a woman during this time. This honor not only put women on the map, but it also helped Hobby down the line in her career. She was called to work with President Eisenhower as head of the Department of Health in 1953, handing funds toward education and healthcare.

In the end, after going through the sources about Oveta Culp Hobby, I started to feel that most of them were bias in the way they portrayed her. Most of the articles started off explaining Hobby’s background into the life of politics, but credited men mostly. Hobby’s husband was the former Governor of Texas William P. Hobby, who was a friend of her father. Oveta Culp Hobby should be highlighted more for her efforts for women during WWII, I didn’t find many sources that goes into depth. I had no idea that Hobby helped create the Department of Health for President Eisenhower in 1953.[48]

Pop culture reflected the war and the mood of Americans during the war. what follows are two essays by my students on comics and cartoons. The former is a written form of entertainment while the latter is a visual, fluid form of entertainment. Students concluded that while the major comics of the time created new super heroes to support the war effort, Walt Disney and other cartoon makers made fun of the enemy, editorialized the enemy, and used racial/racist characteristics to denote a inferiority of both German and Japanese leadership.

Alondra Roman, Spring 2020

The two main comic publishers during the world war II era were Marvel comics and DC comics. Marvel Comics published the superhero Captain America in early 1941. This superhero was a patriotic super-soldier and was the most popular one during the wartime period. He was created by Cartoonists, Joe Simon, and Jack Kirby.[49] Near that time, DC Comics published the most recognizable superheroine of all, Wonder Woman. In late 1941, psychologist and writer William Moulton Marston created this superheroine.[50] Both superheroes were depicted fighting Axis powers of world war II.

The cartoonist Joe Simon and Jack Kirby believed that Captain America was a consciously political creation. They strongly opposed Nazi Germany’s actions leading up to the involvement of the United States in world war II. During the time of war, Captain America was the most important superhero in the war effort. He was envisioned taking down a Nazi villain on his first published solo. On the Homefront, propaganda posters and comic books featuring Captain America were used to inspire support for troops, encourage growing victory gardens, and boost sales of war bonds for military production.[51] On the other hand, writer William Marston worked alongside his wife Elizabeth and developed the superheroine, Wonder Woman whom he believed to be a model of the era’s unconventional, liberated woman. Unlike Captain America, she did not begin with her solo comic book but instead was featured in All Star Comics #8. Marston was a feminist and his experience with polygraphs proved to him that women were more honest and could work more efficiently in certain situations. He conveys Wonder Woman was psychological propaganda for the new type of women he believed should rule the world.[52] Marston’s views on female equality and his belief that women should rule the world, given their greater capacity for love. Wonder Woman became the model for Marston’s ideas concerning female power.

:focal(242x316:243x317)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ff/89/ff89d270-5077-4889-82cd-cfbf965210bd/captainamerica1.jpg)

Overall, it may be said that superhero comics were used as propaganda during World War II in order to encourage soldiers to fight against the Axis, as well as to empower women. Though a fiction story, the creation of Captain America brought forth the idea that all citizens were capable of supporting those abroad. It led to the citizens’ understanding, that they too could contribute to the war effort. The comic book portrayed what was happening through most of the war, and it showed what children and young men could do. Conversely, Marston designed the superheroine to be an allegory for the ideal love leader; the ideal role model for woman. Therefore, a feminine character with massive strength and all the allure of a beautiful woman was created.

Valerie Gonzalez Spring 2020

In this essay I will examine the different forms of World War II cartoons and how they helped Americans combat their anxieties and believe victory was possible.

As the American government prepared to enter into WWII, animation featuring the already adored characters in Looney Tunes and Disney cartoons comforted anxieties. In Disney animation Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck faced obstacles that related to the common man’s struggle which aided Americans in time of despair.[53] In Draftee Daffy released by Warner Bros in 1945 Daffy Duck is at first very patriotic when reading about American Victories in the newspaper though becomes erratically scared when a draft man arrives to enlist him. Daffy tries numerous comedic attempts to get rid of the draft man but continuous to run cowardly away until the end of the short animation.[54] Daffy’s actions were representative of American men recruitment anxieties although Warner Bros comedic approach made these anxieties seem silly to have making American men more comfortable to be drafted as the draft man was reduced to a small harmless man.

Another major fear that Americans held was toward the three axis powers and animation was used to reduce these powers to non-threatening jokes to laugh at. Hitler and Nazis were the main target in these sorts of cartoons. In Duer Fueher’s Face produced by Disney in 1943 Nazis are portrayed as flamboyant and buxom making them more laughable than threatening. The way they parade around in the animation can also be compared to a choreographed theater performance which makes them seem superficial and less manly.[55] Hitler is also portrayed as a superficial dictator obsessed with his image and being respected by others. In cartoons like these Hitler is reduced to an insecure effeminate man which allowed Americans to carry less fear about Germany.

Japan and the Japanese were similarly mocked in cartoons and animation especially after Pearl Harbor. In “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap”, Popeye faces off against Japanese sailors on a Japanese Ship. Popeye is able to singlehandedly take on the Japanese sailors who are stereotyped as buffoons whose antics seem more like childish pranks rather than honorable battling. The Japanese weapons and ship are similarly shown to be incompetent in the animation as they are unstable and fall apart in an instant as opposed to the American ship that Popeye escapes on to safety in an instant. These sort of caricatures of the Japanese make these enemies seem like Americans were facing off against a bunch of kids, victory was inevitable it seemed.[56]

Animated cartoons were a successful format to address American fears in a comedic way. The lovable characters and silly caricatures of American enemies gave confidence to the United States War effort.

Finally, Adam Izaguirre found out that sometimes war indeed makes strange bedfellows.

Though war was brought to us by a foe who was consumed by controlling the world, there was another war front, a more secretive front that was fought by those who we didn’t think the army would ask for help.

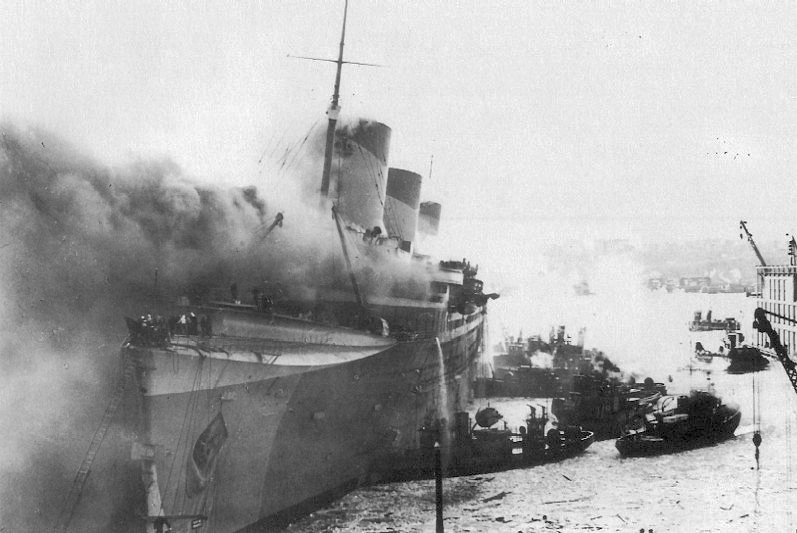

By 1942 to 1945 the government will collaborate with a local mafia mobsters to protect the port from any Nazi invaders that dared to come, it first began with the destruction of a cruise ship that sailed to the U.S from France, from there it made it to the ports of New York, where it was destroyed due to saboteurs in which people started to panic. After the destruction of the cruise ship, the Navy Intelligence swarmed the docks of New York to “solicit the cooperation of the longshoremen to ferret out German spies” which in the end didn’t do anything, even Naval Intelligence had theory; was largely the Italian dock workers were loyal to Hitler, Italy’s Mussolini.[57] There’s no real evidence to support this however, the allegiance for the dock workers was for who any, since all of them were all averse by nature and culture to help out any authorities. In March of 1942 the Naval Intelligence sought the help of a fish market and the Kingpin Joseph “Socks” in which he’ll have “agents operating undercover in the market and aboard coastal fishing fleets” thus Operation Underworld began.[58]

Being extremely concerned the Navy sought out help from New York authorities though soon the prosecutors soon conceded that “waterfront that it enlisted a most unlikely partner in the war effort—the Mafia” the mobsters controlled the docks and that they weren’t idiots especially the ones who were Eastern Europeans Jewish landsman who were rounded up by the head honcho himself, Hitler.[59] After Pearl Harbor Meyer tried to enlist but couldn’t due to his age and height, but something good came out of it, sometime later Meyer had an arrangement with the commander of naval intelligence Charles Radcliffe Haffenden, in which they made a deal, the pitch was; the mafia controlled the docks, and it was suspected that there were Nazi saboteurs and spies hiding out in the docks, and it’s Meyers job to snuff out the mole and have them bring down, though he couldn’t serve in the army he can at least help at the home front. Though he would soon be getting help from his best friend Charles “Lucky” Luiciano who still wielded power while being imprisoned for 6 years, both Lucky and Meyer agreed in helping out the Navy also going as far to give them information on the “amphibious invasion of Sicily by providing maps of the island’s harbors, photographs of its coastline and names of trusted contacts inside the Sicilian Mafia.”[60]

In the summer of 1942, eight nazis saboteur were captured after they came ashore in a u-boat in Jacksonville Florida, they had plans on destroying American defense plants, bridges and railways, but this wouldn’t be their first rodeo soon after they would all be captured “ Their leader turned himself in to J. Edgar Hoover. Some of the others were captured when mob-controlled union members employed at New York hotels reported them to naval intelligence.”[61] Though soon only two would receive long term prison sentences and the rest would be executed by Roosevelt, after the whole charade Meyer helped out with other operations that the Navy would throw at him. Though soon the war would end Meyer tried to redo what he did wrong as a mobster, becoming the czar of Cuba’s legal gaming and resort industries but when it fell to Castro’s hands he lost it all, after that he tried to gain citizenship from Israel but was considered a liability, he was forced back home to Miami, soon he would pass away in 1983.[62]

I want to thank my students Ulises Ramirez, Hector Jovanny Barba, Jada Ballard, Alondra Roman, Valerie Gonzalez, Adam Izaquirre, Leonel Lizalde, Alejandra Lopez, Tatyana Marquez, Damian Mendez, and Paulina Mosqueda for their interest in these topics, dedication, time, and energies necessary to bring these histories alive. Their contributions enhanced this chapter.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Originally attributed to the same source last accessed on 23 June 2003. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/bracero-program (Last accessed 19 NOV 2020). ↵

- Originally attributed to www.rain.org/~artworks/familia/bracero.html (last accessed 23 June 2003) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Originally attributed to the same source accessed 27 FEB 2003. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/zoot-rise-riots/ (Last accessed 19 NOV 2020). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/zoot-rise-riots/ (Last accessed 19 NOV 2020). ↵

- Originally accessed 27 FEB 2003. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/zoot-rise-riots/ (Last accessed 19 NOV 2020). ↵

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/latinoww2.htm#:~:text=The%20result%20was%20massive%20Mexican,of%20belonging%20accompanied%20the%20experience. ↵

- https://homeofheroes.com/medal-of-honor-citation/world-war-ii-medal-of-honor-recipients/ ↵

- Munson carried out his investigation after the US broke the Japanese military code, indicating that Pearl might be a target of the Japanese. ↵

- https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/japanese_internment/munson_report.cfm ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- http://www.sscnet.ucls.edu/aasc/ex9066/ (last accessed 27 FEB 2003) ↵

- By Ulises Ramirez, Spring 2020 ↵

- A Brief History Of Japanese American Relocation During World War Ii (u.s. National Park Service, Manzanar National Historic Site) https://www.nps.gov/articles/historyinternment.htm (last accessed 3/14/2020) ↵

- Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese(1942) [ online] Available https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=74# Last Accessed 3/15/2020 ↵

- In and Out of the Tule Lake Segregation Center: Japanese Internment in the West, 1942-1945Author(s): Rosalie H. WaxSource: Montana The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Spring, 1987), pp. 12-25Published by: Montana Historical SocietyStable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4519047Accessed: 08-03-2020 19:28 UTC ↵

- HOUSTON, JEANNE WAKATSUKI AND JAMES D. HOUSTON. “FAREWELL TO MANZANAR” BOSTON, NY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT PUBLISING COMPANY, 2002. Pg,50 ↵

- “Teinei – What We Can Learn from the Japanese Concept of Politeness A Glimpse of the Beauty of Japanese Etiquette” by Gergana Mileva, Trive Global. January 30, 2018. [Online] Available https://thriveglobal.com/stories/teinei-what-we-can-learn-from-the-japanese-concept-of-politeness/ (Last Accessed 3/15/2020) ↵

- Gila River Relocation Center, javadc.org/gila_river_relocation_center.htm. ↵

- “Japanese-American Internment During World War II.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed March 10, 2020. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation. ↵

- Gila river, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila%20River/#Camp_Life_and_Community ↵

- Kay Matsuoka Segment 19, http://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-48-19/?tableft=segments ↵

- Hane, Mikiso. "Wartime Internment." The Journal of American History 77, no. 2 (1990): 569-75. Accessed March 14, 2020. doi:10.2307/2079186. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- https://www.wwii-women-pilots.org/the-38.html ↵

- https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ40/PLAW-111publ40.pdf ↵

- https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2019/01/15/pioneer-among-female-world-war-ii-pilots-dies-at-96/ ↵

- by Hector Jovanny Barba ↵

- Rickman, Sarah. “Nancy Harkness Love, WWII Pilot & Commander”. Amazing Women in History https://amazingwomeninhistory.com/nancy-harkness-love-wwii-pilot-commander/. 05Dec2019. ↵

- Chen, Peter. “Nancy Harkness Love”. World War II Database. https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=507. 05Dec2019. ↵

- Ibid., 1. ↵

- Herold, David. “Nancy Harkness Love: A Symbol of Pride, Passion, and Perseverance in WW2”. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/nancy-harkness-love-m.html. 05Dec19. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Rickman, Sarah. “Nancy Harkness Love, WWII Pilot & Commander”. Amazing Women in History https://amazingwomeninhistory.com/nancy-harkness-love-wwii-pilot-commander/. 05Dec2019. ↵

- Ibid., 15. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- by Jada Ballard ↵

- Kelly. “Oveta Culp Hobby.” National Women's History Museum. Accessed November 28, 2019. ↵

- Foodie, Honky Tonk. “The First Female Army Colonel Was Texan Oveta Culp Hobby.” Texas Hill Country, June 5, 2019. https://texashillcountry.com/first-female-colonel-hobby/. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, William P. Hobby, Jr., "HOBBY, OVETA CULP," accessed December 08, 2019. ↵

- Hobby, William P., Jr. “Hobby, Oveta Culp.” Handbook of Texas Online. ↵

- “Guide to the Oveta Culp Hobby Papers,1817-1995 MS 459.” University of Texas Libraries. Accessed November 24, 2019. ↵

- Editor. “Captain America: A WWII Fighting Force.” National D-Day Memorial, September 27, 2017. https://www.dday.org/2017/10/19/captain-america-a-wwii-fighting-force/. ↵

- Ormrod, Joan. “The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore, and: Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941–1948 by Noah Berlatsky (Review).” Cinema Journal. University of Texas Press, October 18, 2015. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/595619. ↵

- Onyon, David. “The Political Influence of Comics in America During WWII.” SAGU, August 14, 2018. https://www.sagu.edu/thoughthub/the-political-influence-of-comics-in-america-during-wwii. ↵

- Joyce, Nick. “Wonder Woman: A Psychologist's Creation.” Monitor on Psychology. American Psychological Association, December 2018. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2008/12/wonder-woman. ↵

- Watts, Steven. “Walt Disney: Art and Politics in the American Century.” The Journal of American History, vol. 82, no. 1, 1995, pp. 84–110. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2081916. Accessed 16 Mar. 2020. ↵

- Draftee Daffy. Bob Clampett. Warner Bros. Pictures, 1945. Film. Last Accessed March 15, 2020 ↵

- Duer Fueher’s Face. Jack Kinney. RKO Radio Pictures, 1943. Film. Last accessed March 15, 2020 ↵

- You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap. Dan Gordon. Paramount Pictures, 1942. Film. Last accessed March 15, 2020. ↵

- Eric Dezenhall “Operation Underworld” and https://usnwc.libguides.com/c.php?g=661096&p=6277109 ↵

- Christopher Klein “What is Operation Underworld” https://www.history.com/news/what-was-operation-underworld ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Eric Dezenhall “Operation Underworld” and https://usnwc.libguides.com/c.php?g=661096&p=6277109 ↵

- For more information see the historical novel Operation Underworld by Paddy Kelly and Mafia Allies: The True Story of America's Secret Alliance with the Mob in World War II by Tim Newark, Warfare History Network. ↵