20 The Wages of Manifest Destiny or, How the Sioux Lost Their Culture (1865-1890)

How the Sioux Lost Their Culture

Jim Ross-Nazzal

Although Americans and Indians had been fighting each other since the creation of the United States, the term “The Indian Wars” applies to US-Indian warfare following the Civil War and lasting until 1891. Following the Civil War, more Americans than ever before migrated out West. The idea of “the West” thus was pushed farther and farther west. One of the biggest land rushes occurred in what had been proclaimed to be “Indian Territory” since the presidency of Andrew Jackson: Oklahoma. The first push into Oklahoma occurred within a two million square mile area in 1889 called “No Man’s Land” (the panhandle, directly west of all Indian lands). The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 was the beginning of the end for Indian domain throughout Oklahoma and American settlers increased pressure on Congress to secure and then open more Indian lands for American settlement purposes. The relatively bloodless takeover of Indian Territory was rare in the history of the American West, especially when compared to the experiences of the Sioux.

From the 1830s through the Civil War, the US policy on dealing with the Indians was know as consolidation: compel Indians to migrate creating densely populated Indian areas, such as Oklahoma for many of the Eastern Indians or parts of Arizona for the Indians of the American southwest. Just like American sought to conquer the wilderness thus Americans needed to conquer the Indians. Mass extinction through the use of warfare was not universally accepted by Americans in the early nineteenth century. However Indians could not be allowed to stay on their ancestral lands because of the promise of wealth intrinsic to those lands. For example, the California gold rush of the late 1840s brought hundreds of thousands of Americans out West, creating new westerward routes which cut through established Indian lands. Indians were thus seen as an obstacle to western migration and thus Indians needed to be removed. Tasked with primarily dealing with the “Indian problem” was the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Although extinction was not the official US policy, there was nonetheless endemic warfare between Indians and the US government throughout the nineteenth century. For example, Apache Indians fought both American settlers as well as the US military’s attempts to force the Apaches to leave their ancestral homes of Texas and New Mexico to settle on a reservation in southern Arizona. The US constructed dozens of forts throughout the West and by 1865 military force was the primary agent of change.

The Sioux Reservation

Indians were moved from richer, more attractive lands to less viable, less attractive lands. In the case of the Sioux (which consisted of numerous types of Sioux such as the Dakota, Lakota, and Nacota), these Plains Indians were consolidated onto the Sioux Reservation from places like Minnesota in he east and Nebraska in the south. Reservations were well-defined tracts of land, where Indians could live without getting in the way of west ward expansion. The use of the military was the driving force behind the policy of consolidation through the Civil War and by 1865 the US had experienced military supremacy throughout the West. However, in 1865 the Dakota territorial governor, Newton Edmunds, called on Congress to begin peace initiatives with the Indians. Dakota was a war torn territory. And more white settlers were leaving Dakota than arriving so the people of Dakota sought to bring an end to its endemic warfare in order to be able to grow its white population. In October of 1865, Edmunds traveled along the Missouri River proclaiming peace.

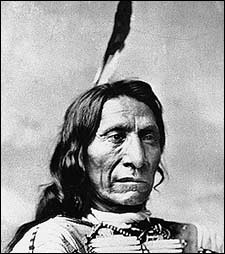

At the same time, Congress negotiated a peace treaty with the Kiowas and Comanches of Kansas. With the Civil War behind them, it appeared that the US had adopted a new way of dealing with the Indians. One of the Sioux’s military leaders was named Red Cloud, an Oglala Sioux. After many years of fighting other Indians, and in the face of destitution following a particularly harsh winter, Red Cloud was receptive to the US government’s peace initiative and thus the two sides met at Fort Laramie in June of 1866. But, the US government did not speak with one voice on Indian issues. On one side were those who supported the military solution such as Generals Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Phil Sheridan as well as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

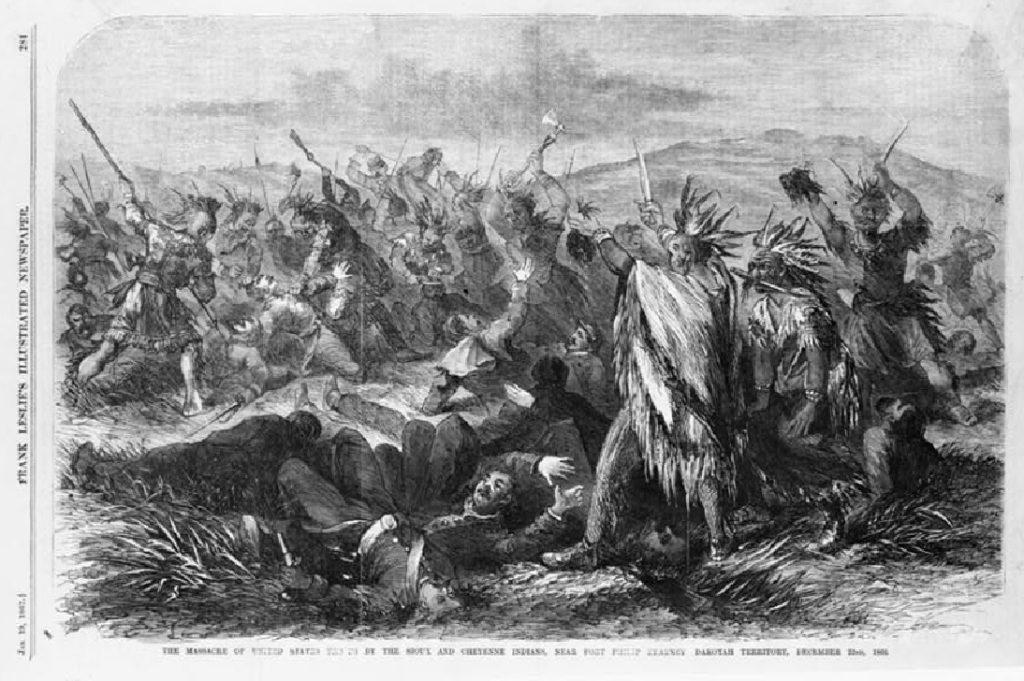

Supporting the new peace policy were the Secretary of the Interior Orville Browning, Nathaniel Taylor (head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs), and members of the Senate such as James Doolittle and John Henderson. Although Red Cloud was interested in the US peace initiatives, he also demanded that white settlers stop using the Bozeman Trail and threatened to attack any whites who migrated through Sioux Territory on the trail. Indian-US tensions were high and in December of 1866 Sioux warriors lured a detachment of troops out of the Bozeman Trail post of Fort Phil Kearny. This was a decoy, which was led by the young, up-and-coming Sioux warrior Crazy Horse (see essay at the end of the chapter for more on Crazy Horse).

As the soldiers left the safety of the fort, the Sioux fell back and the soldiers pursued. Nearly two thousand Sioux warriors came out of their hiding places and ambushed the troops, who were led by Captain William J. Fetterman. The Fetterman Massacre became a national debate. “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux,” said General Sherman.

In January of 1867, Senator James Doolittle published a report on the health and welfare of the Plains Indians. They were dying. They feared white encroachment and Indians would continue to attack white settlers as long as the Indians fear that they are losing their lands. Thus Doolittle concluded that the solution to the Indian policy lay in the reservation system. Not only should land be set aside specifically (and in perpetuity) for Indians, but that Indians must be civilized: they need to learn how to farm and become self-sufficient, their children need to attend school, and Christian missionaries must be sent to help in their spiritual transformation. Indians of the Northern Plains wanted peace and they wanted a secure parcel of land and so the commission set up to investigate the Fetterman Massacre called to close the Bozeman Trail and to create two parcels of land for Indians along the Missouri and Yellowstone river basins. All Plains Indians would be consolidated on these two reservations. In October of 1867, members of the US government and representatives of Indians signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty. The Medicine Lodge Treaty allowed Indians to hunt buffalo in specific areas for as long as the buffalo roamed; Indians would get an annual annuity for thirty years, and immediately upon signing the treaty Indian leaders would be given beads, buttons, bells, pans, cups, knives, blankets, bolts of fabric, coats,hats, and arms and ammunition. Upon signing the Treaty Indians pledged to take up the plow, get their children educated, and yield all lands outside of the reservations to the US government.

The following year Sioux and American representatives signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, which created the Sioux Reservation surrounding the Black Hills. Also in 1868, Indians gathered at Fort Larned to receive their first annual annuity issued under the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Some of the Indians were restless and attacked white settlers over a two-day raid. The US military response was quick and it looked like Congress was going to abrogate the Medicine Lodge Treaty by sending the US military to round up the Indians and compel them to stay on the reservation.

The Grant Presidency, 1871-1879

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant ushered in a new era of US-Indian relations, “All individuals disposed to peace will find the new policy a peace-policy,” said Grant on the eve of his inauguration. Grant’s peace policy centered on the old reservations where Indians would be civilized by American missionaries on how to till the land, educate their children, and convert to Christianity. That was not new. What was new was the abandonment of the treaty system. The Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 barred the US government from ever entering into treaties with Indians. Grant sent military and Christian missionary emissaries out West to meet and make peace with Indians. For example, Grant sent the old Civil War general Oliver O. Howard to negotiate peace with Cochise, an Apache leader. Even Red Cloud wanted to talk to the new president.

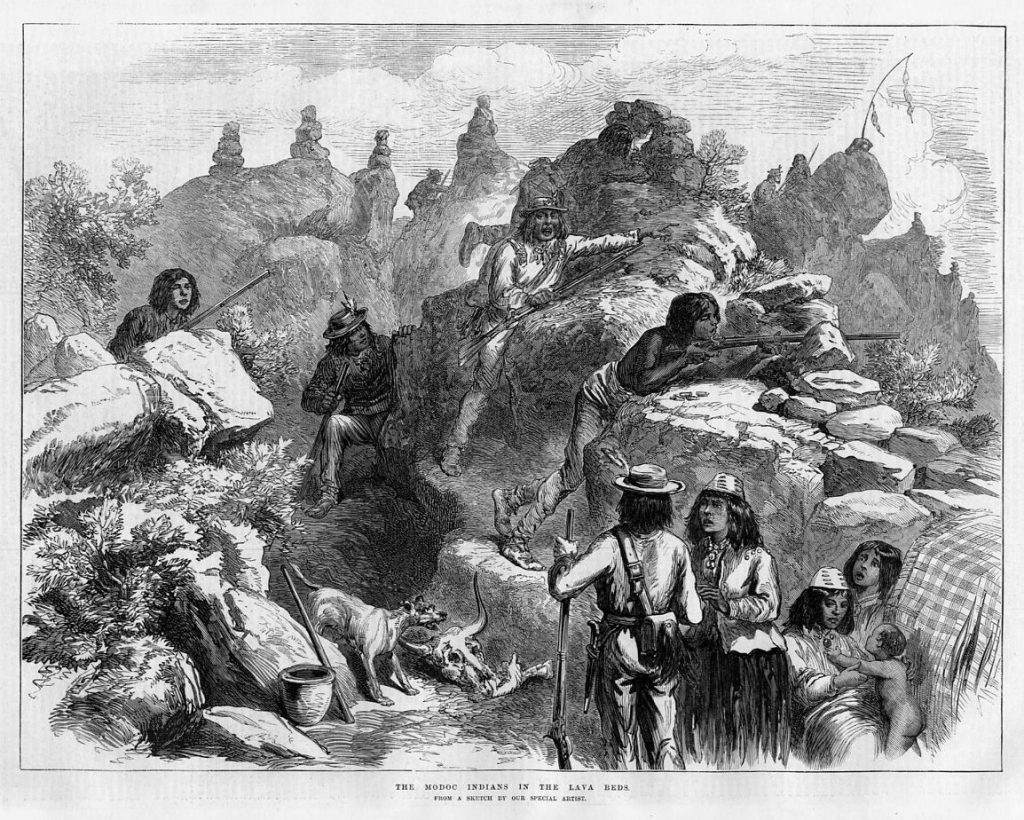

Peace, nonetheless, did not break out throughout the West. For example, Modoc Indians of California left the reservation and held off the US army for most of 1872. When peace talks began in 1873 Modoc leaders ambushed the American representatives and the fighting resumed. The Modoc War almost ended Grant’s peace policy. In northern Texas Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowas attached US settlements which resulted in a military response from the US. Even the Sioux Reservation was threatened in the mid 1870s when an expedition led by General George Armstrong Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills. Discovery of gold resulted in thousands of Americans ignoring the boundaries of the Sioux reservation. One of the largest white settlements within the borders of the Sioux reservation was Deadwood. Deadwood was so economically important that the city received the telephone in 1877.

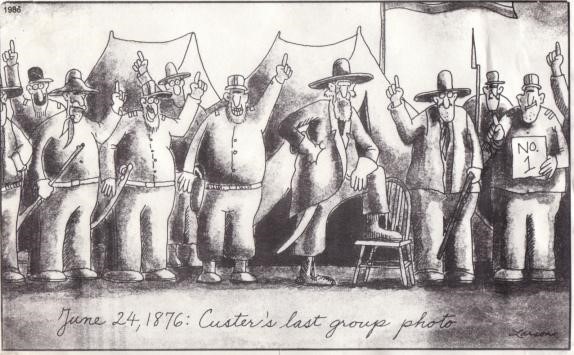

To keep the Sioux and white settlers apart, the US government demanded that all Sioux return to their reservations, or else. In the summer of 1876 Sioux warriors and the US Army skirmished along the Powder River. Sioux leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse prepared for war and by the early summer of 1876 Sioux encamped along a river they called Greasy Grass and had earlier performed the Sun Dance in which Sitting Bull received a vision of American troops would die in the Indian camps. Crazy Horse took a large force to meet the US Army along the Rosebud River. The clash lasted for six hours before both sides withdrew. Tensions mounted. Believing that he was on a mission from God, and believing in his invincibility, General Custer, with only a few hundred troops, attacked the main Sioux encampment along the Greasy Grass river (which the whites called Little Big Horn) on Sunday, June 25th, 1876. Custer and his Seventh Calvary were wiped off the face of the earth, disproving Custer’s position.

Fighting continued throughout the fall and into the winter when Colonel Ranald Mackenzie launched an attack against the Cheyenne villages of Dull Knife and Little Wolf. The surviving Cheyenne took refuge with Crazy Horse. In January of 1877 Sioux-Cheyenne clashed with the US army. Grant’s peace policy was in shambles. After the battle of Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and some of his Sioux followers fled to Canada. Likewise the Nez Perce (of northern Idaho) refused to be placed on a reservation and thous they began a 1500 mile trek to link up with the Sioux in Canada. The US government sought to prevent that so Generals Nelson a. Miles and Howard were sent in pursuit of the Nez Perce. On September 30th, 1877, less than forty miles to the Canadian border, Miles and the Nez Perce clashed. But,many of the Nez Perce avoided capture and continued their march to freedom. The leader of the Nez Perce was named Chief Joseph. Joseph’s people were staggered all over northern Idaho. Crossing the Bitteroot Mountains in winter is a formidable task and many of his people fell to the elements. Wanting to bury the dead and round up the children, on October 5th, 1877 Chief Joseph surrendered. “I am tired of fighting . . . My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I shall fight no more forever,” he said. The Nez Perce were rounded up and sent to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Missing his ancestral lands, Sitting Bull returned from exile in 1881 and surrendered to US officials, marking the end of the Plains Wars.

Adam Izaquirre writes, “By July of 1878 the people who were 400 at the time were brought to the Quapaw agency in the northeastern side of Indian territory. There the Nez Perce were close to the Oklahoma border with Arkansas and Missouri. From then on, the Nez were in a pretty bad spot. Having little rations to share around them ‘…and no quinine was available to treat the 265 prisoners suffering from malaria.’[1] From this more than 70 died in October of 1878, one of the worst concentrated loses experiences by the prisoners in the camps.”

Reformers and the Indians

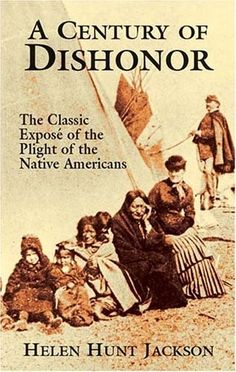

In upstate New York, American reformers met annually to discuss their ideas on helping American Indians in their transformation from “savage” to “civilized.” The Lake Mohonk home was owned by Quaker brothers Albert and Alfred Smiley. The Smiley’s home was so large that they turned it into a resort and every summer the well-educated Protestant elite of New York came to Lake Mohonk. Starting in 1883, the Smileys began to host an annual meeting of like-minded reformers. One of those in attendance was a woman author named Helen Hunt Jackson. In 1881 she published an expose on US-Indians relations called “A Century of Dishonor.” Another reformer was Clinton Disk who created Fisk University to help the ex-slaves in their transition from slavery to freedom. These reformers embraced a simple mechanism for helping American’s Indians and it was known as Americanization. Americanization was the convergence of American nationalism and American protestantism. The ideal American, according to this belief, lived a Christian life according to Protestant principles, was self-sufficient, and was an uncritical supporter of everything American.

The first step was to “detribalize” Indians -to break all tribal connections such as the roles of chiefs and medicine men, remove all communal ways of being and thinking. The second step was then to substitute American ways of being and thinking. Reformers sought to ultimately get rid of the reservations themselves because true Americans did not live communally. Private property was the driving force of America. A Mohonk supporter was the US Senator from Massachusetts, Henry L. Dawes. Congress followed suit by passing, in 1887, the Dawes General Allotment Act. The Dawes Act was an attempt to Americanize the Indians. First, communal lands would be replaced with private property. Each head of the household would receive 160 acres of land, each single male would receive 80 acres and each child 40 acres. The federal government would hold the land in a trust for twenty-five years. For twenty-five years Indians would have to successfully use the land for farming and grazing. They had to forswear all aspects of Indian culture. If, after twenty-five years, the Indians successfully transformed themselves into Americans then they would get ownership of the land. All tribal lands in excess of the 160 acres allocations would be sold by the federal government.

Wounded Knee, 1890

Throughout US history the US government signed numerous treaties with Indians, to include treaties creating the Sioux Reservation centered on the Black Hills of what is today South Dakota. The Black Hills held a religious significance to the Sioux. In the 1870s gold was discovered in the Sioux reservation and thousands of Americans ignored the Sioux reservation treaty and poured into the reservation, setting up camp in the town of Deadwood. Of course if the Indians attacked the whites, the US government would respond in kind thus the Indians and the settlers lived in a rather tense existence. Deadwood was such an important mining town that the telephone was introduced in 1877. A year before the US government sent in General George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry Division into the Sioux reservation to keep the Indians apart from the white settlers.

Many in Congress, led by US Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, saw the reservation system as un-American. In the reservation system Indians collectively owned the land and, for the most part, they hunted and engaged in traditional socio-cultural activities. We need to help the Indians transform themselves from “savages” to citizens and to start Congress will divide the Sioux reservation into family parcels. Each Sioux family would receive approximately 250 acres of land and ownership of the land was be transferred to the head of each Indian family after a twenty-five year period. During those twenty-five years Indians were required to break all ties to their traditional ways of life: no more hunting buffalo, or performing the Ghost Dance, or wearing traditional clothing.

“What the Indian needs is pants with pockets, pockets that yearn to be filled with gold,” Julius Seelye, President of Amherst College said. For more on Julius Seelye, see the essay below by Gwendolyn Bellew at the end of this chapter.

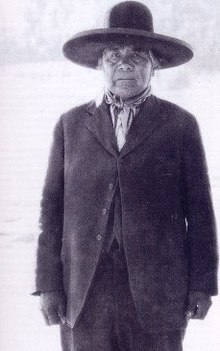

In fact Sioux children would be sent off to one of the new “Indian schools,” such as the famous Carlyle School in Pennsylvania where Indian children would have their hair cut in accordance to American styles, dress in American clothes, be taught English and American history, and eventually returned to their parents. With only handing over around 100 acres per family, there were millions of what Congress called “excess” lands, which would be sold off to various railroad interests. Older Sioux leaders such as He-Kills-First, Sitting Bull, or Big Foot rejected the Dawes Act while younger Sioux warriors supported the government plan, especially those who the federal government “promoted” to join the Sioux police force as they received the best food, clothes, and of course weapons. The result was a divergence within the Sioux community, at times sparking violence between the older and younger generations. The old chief Sitting Bull was more than just a raspberry seed in the Sioux police’s wisdom teeth. He was fomenting rebellion so on December 15th, 1890 Sioux police went to arrest Sitting Bull. The melee that followed resulted in Sitting Bull being shot and killed by the reservation police.

General Miles sent this telegram from Rapid City to General John Schofield in Washington, D.C., on December 19, 1890:

“The difficult Indian problem cannot be solved permanently at this end of the line. It requires the fulfillment of Congress of the treaty obligations that the Indians were entreated and coerced into signing. They signed away a valuable portion of their reservation, and it is now occupied by white people, for which they have received nothing.”

“They understood that ample provision would be made for their support; instead, their supplies have been reduced, and much of the time they have been living on half and two-thirds rations. Their crops, as well as the crops of the white people, for two years have been almost total failures.”

“The dissatisfaction is wide spread, especially among the Sioux, while the Cheyennes have been on the verge of starvation, and were forced to commit depredations to sustain life. These facts are beyond question, and the evidence is positive and sustained by thousands of witnesses.”[2]

Around that same time a Ute cleric named Wovoca had a vision and in that vision his ancestors told him that Indians must engage in inter-tribal cooperation and perform a new ritual called the Ghost Dance. By dancing in a circle, men would commune with the dead, getting strength from the dead and working in conjunction to push the White settlers off Indian lands. In December 29th of 1890, the reconstituted 7th Cavalry division was sent to the reservation town called Wounded Knee to meet with tribal leaders and reservation police in order to try to put an end to the ghost dance. Fearing that violence was imminent and not wanting a repeat of history, members of the 7th cavalry began to disarm the Sioux, going from tepee to tepee taking guns, knives, anything that could be used as a weapon against the troops. The troops then segregated the men from the women and children and armed with a new repeating rifle and cannons, the troops opened fire. A reported watching the attack said that children leaving the school house when the guns hit them was like watching grass before the sickle. Numbers vary wildly from 150 to 300 men, women and children killed with over 50 wounded who survived. The lifeless bodies froze in the late December weather and after nearly 500 years of constant Anglo-Indian warfare, this was how the Sioux lost their culture.

What follows are brief essays by two of my students. Gwendolyn Bellew researched and wrote about Julius Seelye and Mishaly Blackshire looked at Crazy Horse, both in the Spring semester of 2019.

Julius Hawley Seelye was an accomplished man in many areas: theology, philosophy, and even public service. Despite a lack of formal educational in his younger years, Seelye went on to achieve a multitude of diverse successes. Through a combination of his life experiences and beliefs, he made many successful contributions to collegiate procedures, such as his development and deployment of the “Amherst Plan” and his changes to Amherst College policies.

Born in Bethel, Connecticut, on September 14, 1824, Seelye’s childhood outlook was bleak. He was nearsighted, which caused him to be presumed unintelligent. He was set on a path to become a merchant, like his father. After being encouraged by a friend to pursue a college education, he went against his parents’ wishes and enrolled at Amherst College in 1846.

Upon graduating, Seelye went on to study at the Auburn Theological Seminary. From there, he traveled to Europe where he studied Philosophy at the University of Halle. “Returning to the United States in 1853, he was ordained to the ministry on 10 August of that year in Schenectady, New York, where he held the pastorate of the First Reformed Dutch Church for the following five years.”[3] He did this while continuing his study of Philosophy. In 1858, Seelye returned to Amherst College as Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy, where he was recognized as a valued faculty member.

In 1874, Seelye became involved in civil service. He was appointed to a commission for revising tax laws of Massachusetts. Soon thereafter, he was encouraged to run for the U.S. House of Representatives for the tenth district of Massachusetts. He won the election despite not spending any money or campaigning. He was nonpartisan in all his actions, even going as far as to object to the Electoral College regarding the 1876 Presidential election. Though the Electoral College found that Hayes, for whom Seelye had voted, had won the election, Seelye believed Tilden had won.

After his political service, Seelye returned to Amherst College in 1877, where he was appointed president. He also taught Philosophy and was the college church pastor. During Seelye’s inaugural address, he “effectively prohibited the teaching of evolution on Amherst’s campus.”[4] This was met with defiance by the professor of geology and zoology, who continued teaching evolution, while other professors and departments began teaching in accordance to creationism. Seelye, firm in his beliefs, responded with the removal of geology courses as required courses, and later only offered the courses as electives. As president, Seelye “inaugurated at Amherst what is said to be the first instance of student self-government on record in any American college.”[5] This became known as the “Amherst Plan” and was used to implement student governments in many colleges. These policy changes were key to the transformation from traditional finishing college to the more contemporary college concept. Seelye continued in his roles at Amherst until his retirement in 1890. He passed away just a few years later, on May 12, 1895.

Julius Hawley Seelye led a life of commitment to his beliefs and applied those beliefs in all aspects of his life. He utilized his knowledge of theology and philosophy throughout his life to accomplish new and innovative concepts, such as the “Amherst Plan” and the modernization of college institutions.

“Another white man’s trick! Let me go! Let me die fighting!” stated Crazy Horse, a Lakota war leader and warrior. He fought for the rights of his people to live their culture as they pleased, and in this essay, I will be analyzing his legacy. The white people decided that it was their duty to colonize the Native American people in which the Native Americans refused. They believed that the Native Americans needed to be punished for not submitting willingly to white authority or not getting out of the way fast enough or simply dying fast enough for land hungry whites.[6] The whites retaliated and decided to go to war believing this would force them to colonize freely. This act only fumed the Natives to protect their culture. Crazy Horse fought in battles after battles coming out with victories each time for his people no matter what obstacle the white’s put in his path. There were three important kinds of warriors recognized by the Sioux. A young man strove to be a great fighter of battles, a great scout, or a great hunter.[7] Crazy Horse happen to be one of the few who has excelled at them all. Instead of trying to force the Native’s to live identical to them the whites were beating down Indians who expressed any independent thinking, rewarding them with positions of importance and completely stifling independent and creative thinking from the Indian people, having, different laws apply to him, setting up a different kind of government.[8] Crazy Horse was arrested in September, taken to Fort Robinson, and ultimately killed by a soldier, perhaps after the Indian warrior resisted being locked in a guardhouse.[9] In todays time while the Natives are showing how these “ancient customs” served to connect, they are sure to mention Crazy Horse accomplishments and bravery.[10]

Phoebe Ann Mosley, also known as “Annie Oakley,” (1860-1926) challenged that idea. Annie was a renowned sharpshooter, besting even her future husband. She participated in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, and even went on to attain the number two spot on the show. Her amazing accuracy with shooting earned her the nickname “Little Sure Shot.” Annie remained involved in western shows for seventeen years, thanks to her skills. Despite her abilities as a sharpshooter, she was also a fierce advocate for women’s rights, and often campaigned for equality in pay and employment.[11]

Another woman who also shined in the western scene was Martha Jane Canary, also known as “Calamity Jane” (1855-1903). Martha was a professional scout and frontierswoman, but she also found herself participating in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. It was not just her involvement in these activities that made her famous, her personality and appearance was far from what the typical woman of her time should have been. In life Calamity Jane broke countless stereotypes of the ideal Victorian woman, being ever so fearless in the name of adventure and even competing alongside the men.[12]

Although the West was a place filled with opportunity, it was also a dangerous territory: the perfect place for outlaws and gunslingers to emerge. One of the women who seized the opportunity of this rising phenomenon was Rose Dunn, also known as “Rose of the Cimarron” (1878-1955). In her early teenage years, Rose became involved with an outlaw named George “Bittercreek” Newcomb, who was a member of The Wild Bunch gang. She was an active participant in all their schemes including robberies and shootings. Rose was also known for supplying ammo to her fellow gang members, but what made her stand out in the gang was her devotion to George. On multiple occasions, Rose ran through gun fire, just to assist her lover. Despite eventually leaving this lifestyle, Dunn earned herself the reputation of a notorious outlaw.[13]

In essence, the idea that a woman was only meant to have a few roles in life was challenged by these three women alike; all three engaged in “unwomanly tasks” without fear of being scrutinized to prove they had the abilities to do so.

I’d like to thank Adam Izaguirre, Gwendolyn Bellew ,Mishaly Blackshire, Sarea Crouch and Anayeli Ledesma for their interest in western history. Their contributions made this chapter more interesting.

As with the other chapters, I have no doubt that this chapter contains inaccuracies, therefore, please point them out to me so that I may make this chapter better. Also, I am looking for contributors so if you are interested in adding anything at all, please contact me at james.rossnazzal@hccs.edu.

- Samvit Jain, Leader and Spokesman for a people: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce, 122 ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wounded_Knee_Massacre Last accessed January 20th 2019 ↵

- Julius Hawley Seelye." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. 6th ed. Accessed February 21, 2019. ↵

- Shook, John R. The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Philosophers in America from 1600 to the Present. London: Bloomsbury, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2019. ↵

- "Julius Hawley Seelye." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. 6th ed. Accessed February 21, 2019. ↵

- Petersen, Tore. Military Conquest of the Prairie: Native American Resistance, Evasion and Survival, 1865–1890. Sussex Academic Press, 2016. ↵

- Kadlecek, Edward, and Mabell Kadlecek. To Kill an Eagle : Indian Views on the Death of Crazy Horse. Boulder: Johnson Books, 1981. ↵

- “It Set the Indian Aside as a Problem” A Sioux Attorney Criticizes the Indian Reorganization Act, August 18, 2016. ↵

- George Kills in Sight Describes the Death of Indian Leader Crazy Horse, August 18, 2016. ↵

- Otto, Paul. The Journal of American History 100, no. 2 (2013): 498. ↵

- Anderson, Ashlee. “Annie Oakley.” National Women's History Museum. Accessed February 8, 2020. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/annie-oakley. ↵

- Etulain, Richard W. "Calamity Jane : A LIFE AND LEGENDS." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 64, no. 2 (2014): 21-94 ↵

- Lyman, and Dave Alexander. Legends of America. Accessed February 8, 2020. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/rose-dunn/. ↵