4

Clint Yingling

Every year, wildfires burn hundreds of thousands of acres, threatening the lives of human and animal inhabitants and private property. According to the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC, 2021), between 2010 and 2020, 63,000 wildfires burned an average of 6,579,343 acres per year in the United States. Fighting wildfires is getting more costly as they become larger and threaten communities and properties. Wildfires, like many disasters, cross-jurisdictional boundaries affecting every local, state, and federal agency and cost millions of dollars every year. This project will look at the way federal and state agencies manage wildfires and an analysis on data from the Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands on the causes and number of acres burned by wildfires in Utah. Although there are several different land owners in the state, the primary focus of this project is on the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and state and local agencies. Together, wildfires occur most often and burn the highest number of acres within each of the four jurisdictions.

There are four categories of land ownership in Utah — federal, tribal, state, and private. The federal government owns 63% of the land in Utah, which is managed by:

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

- United States Forest Service (USFS)

- Fish Wildlife Services (FWS)

- National Park Services (NPS)

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

- Department of Defense (DOD)

The state of Utah, counties, municipalities, and private entities (organization or individual) owns the remaining 37%. This research aims to understand wildfire management at the federal, state, and local levels and the different causes of wildfires across each jurisdiction. An essential aspect of wildland fire management is the land management practices used by each agency to reduce, suppress, mitigate, or attack wildfire. Without proper land and forest management, wildfires will only become more destructive.

In addition to land management practices, other factors contribute to and complicate the topic of wildland fire. Different agencies not listed, such as the EPA and Utah Division of Air Quality (DAQ), regulate activities that may affect public health and safety, such as prescribed burns. Although some argue that prescribed burns are a helpful forest management tool, these two government entities are responsible for ensuring that public health is considered. Drought conditions also play a significant role in land management decisions, given that more extreme drought conditions are likely to increase the likelihood of wildfire.

Background

Many researchers have pointed to land management practices over the last century as one of the primary factors leading to an increasing number and the growing size of wildfires in recent decades. The history of wildfire management policy began in the 20th century alongside the conservation movement. Throughout the 19th century, there was no cohesive national wildfire management strategy even though there were several instances of large wildfires burning hundreds of thousands of acres and killing many people. According to Alan MacEachern, in Maine and Canada, the Miramichi fire of 1825 killed 160 people and burned more than fifteen thousand square kilometers of forest (MacEachern, 2020). In 1825, another fire in Maine broke out alongside the Piscataquis River Valley and burned 832,000 acres (Geller, 2020). The Peshtigo Fire of 1871 burned between 1.2 to 1.5 million acres and killed more than 1,200 people in Michigan (Estep, 2021).

Eventually, the United States Forest Service was created in 1905 and established a professional workforce dedicated to “scientific forestry” and public service, including wildfire management (Williams, 2005). In 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act, which allowed the federal government to partner with states and private individuals to put out fires. In contrast, previously, the FS could only get involved in the fire crossed into Forest Service land. In 1924, Congress passed the Clarke-McNary Act, which was significant because it allowed the FS to support the states financially in their efforts to combat wildfires. Still, it also required states to adopt a fire suppression policy (Stephens & Ruth, 2005). For the South, this policy was controversial because they had a long history of using controlled burns to maintain their forest and held funding as leverage to prevent controlled burns (Johnson & Hale, 2002). In 1935, the USFS established their “10 a.m. policy,” which stipulated that fires should be controlled or put out by 10 a.m. the day after they were first reported (Williams, 2005).

Over time, the debate over the management of public lands and wildfire had shifted from suppression-only to the idea that fire could be used as a tool and was beneficial for maintaining healthy forests. In 1943, Florida NPS used prescribed burning in the Osceola National Forest and again in 1947 in the Francis-Marion National Forest to improve the habitat for wild turkeys (Johnson & Hale, 2002). In the following decades, wildfire practices and the theories of land management have evolved on this topic in response to the growing number of wildfires, acres burned, and the increasing cost of fighting fires appropriated every year by Congress.

The two federal departments that oversee wildfire management are the DOI and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). In 2021, Congress appropriated $1.3 billion to the DOI, divided between the BLM, FWS, BIA, and NPS, and $4.2 billion to the FS. One of the challenges over the last few decades wildfires have taken up a larger percentage of the agency’s budget, so agencies constantly have to shift money away from other programs to fund wildfire suppression. To resolve this, Congress passed the Flame Act in 2010, which created a separate emergency fund specifically for wildfire management.

In Utah, there are three wildfire responsibility areas, including federal responsibility area (FRA), which the federal agencies manage, state responsibility areas (SRA), and local responsibility areas (LRA), both managed at the state and local level. The FFSL is primarily responsible for the state’s response to wildfire but does coordinate with counties, municipalities, and fire districts when applicable. State and local fires are coordinated through the FFSL, county fire wardens, and local fire departments.

Literature Review

In this section, several sources detail both the history, policy, and data that helped shape the conclusion of this analysis. Most of the literature review synthesizes the documented history of wildfire policy, data on wildfires, and the constraints in wildfire management. Many academic research on this topic favors using controlled burns or fire as a tool to manage forests. The increase in the number of fires and acreage burned highlights some of the problems with the suppression-focused fire management policies of the early and middle of the 20th century. However, the literature presents a much more complicated perspective of wildfire management in the 21st century.

Background on Wildfire Management in the U.S.

The formal history of wildfire management in the United States started in 1905 with the creation of the U.S. Forest Service. At the time there was no national guidance for how to manage wildfires. According to Lueck (2011), it wasn’t until the wildfires in 1910 that burned 3 million acres across Wyoming and Idaho that the U.S. developed a national wildfire policy. Shortly after creating the Forest Service, they began developing a national suppression policy that stayed in place for several decades. However, there was some push back from Southern states which had been using controlled burns as a forest management tool throughout the 19th century.

Johnson and Hale (2002) found that the debate in the South over prescribed burns was due, in part, to the threat fires posed against the economic interests in the South and disagreement over the scientific management of forests. Some believed that fire was used as a tool to maintain healthy forests while others argued that it created underdeveloped and undesirable trees and damaged the soil. From an economic perspective, pulp and paper was a growing industry and fire was perceived as a threat to those interests. To support the national suppression policy, Johnson and Hale (2002) wrote, “In the 1940s, the National Advertising Council, the U.S. Forest Service, and state forestry agencies created what has been called the most effective advertising campaign in history: the Smokey Bear program” (Johnson & Hale, 2002). The Forest Service regularly pushed back against the use of prescribed fires. However, by 1971, the Forest Service held a symposium recognizing the value that prescribed burning has had in the South and in other parts of the United States. More recent studies found that nearly 70% of all controlled burns occur in the South.

M.P. North et al. (2015) argued that wildfire policy has failed because suppression is still, in large part, the primary focus of wildfire efforts, leading to more accumulated fuels, which makes fires larger and more intense (North et al., 2015). Prescribed fires are useful for building fire resilient communities. However, the risks of those fires getting out of control and the smoke coming from those fires make federal agencies hesitant to use fire as a management tool. Compared to mechanical thinning, North et al. argue “fire is usually more efficient, cost-effective, and ecologically beneficial than mechanical treatments” (North et al., 2015). However, there are more concerns with liability and less tolerance for mistakes, especially if the situation gets out of control.

North and his colleagues proposed some policy changes that may improve forest and wildfire management over time. For instance, the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) is used to coordinate and deploy resources to combat wildfires. North et al. suggest that maybe agencies could hire specific units trained to conduct controlled burns through designated areas. There are some examples of these crews but are pulled away to assist on active fires. The second suggestion would require the EPA to change its classification of prescribed fires to match unplanned wildfire events which are unregulated (North et al., 2015).

Looking at wildfires between 1984-2011, Dennison et al (2014) found that there has been an increase in the number of large fires and the number of acres burned per year in the western United States. There are a number of factors that are contributing to the increase in fire activity that are separate from forest management practices included drought, precipitation levels, and ecological changes such as invasion of non-native species in certain regions. These are important factors to take into consideration when thinking about wildland fire management or forest management decisions.

More recently, Stephens and Lawrence (2005) reviewed some of the histories of wildfire management, administrative complaints, and the policy and politics of wildfire management. There is a significant amount of data and scientific research on the best wildfire management process. However, the final say is left up entirely to federal, state, and local policymakers. Certain budgetary constraints prevent agencies from being more proactive or reforming their processes. They argue that the focus should be on the reduction of fire behavior and effects instead of only trying to reduce forest fire fuels (Stephens & Ruth, 2005). At the time, there was no budgetary fix for the increasing cost of wildfire management, however, five years later, Congress passed the FLAME Act fixing this issue. The FLAME Act gives additional money to federal agencies for suppression costs to avoid shifting money away from other important programs.

Federal Agency Management

The USFS and the DOI receive congressional appropriations used for wildfire management purposes at the federal level. They each receive funding for preparedness, suppression operations, and other operations conducted (Gorte, 2011). In FY 2021, congress appropriated $5.543 billion to the FS and DOI for wildfires (Congressional Research Service, 2021). The Forest Service received 4,240 billion, and the DOI received 1,302 billion. Each agency’s funding for preparedness goes to training, education, infrastructure, equipment, and resources. The suppression line item goes to putting out or suppressing fires and can include paying firefighters and support operations. Congress appropriates money for fuel reduction measures to reduce the wildfire risk.

Utah Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands

The FFSL’s responsibilities include executing a plan that protects private and public property, watershed areas and encouraging private landowners to preserve, protect and manage forests and other lands. Five engine crews in the FFSL make up the Lone Peak Conservation Center: Lone Peak Hot Shots, Alta Hot Shots, Twin peaks Dromedary Peak, and the Lone Peak Engine crews.

In 2017, Utah switched from a suppression-centered approach to a risk reduction policy, allowing counties, municipalities, and special services districts to partner with the FFSL. The state allocated $1.9 million to fund several projects in the central, Wasatch, north and southeast, bear river, and southwest parts. The projects include grazing, fuel break lines, increasing water tower capacity, and mechanical thinning.

Prevention

Prevention is one of the most important steps agencies can take to mitigate wildfires. Humans cause a significant number of wildfires, so it’s important to take the necessary steps to educate the public about wildfires. The state created utahfiresense.com, which is part of an education campaign about the several ways humans have caused and could in the future mitigate wildfires. Common causes of wildfires started by humans listed on their website include:

- Dragging chains on cars

- Tractors, off-road vehicles, and other equipment that spark fires

- Not properly putting out campfires

- Shooting guns near dry grass and rocks

- Lighting fireworks near dry grass

In September 2020, KSL reported fireworks set off near dry grass by three teenagers and a parent responsible for a 12,000-acre wildfire. The wildfire cost more than $2.5 million to put out. Education campaigns about preventing many of the human-caused wildfires from occurring are essential in the prevention process.

Prescribed Fire

In Utah, the FFSL and DAQ have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), allowing the DNR to use fire as a management tool. As part of their agreement, if there is a prescribed burn larger than 20 acres, the FFSL has to outline a plan regarding the strategy and management of the fire. Depending on the size, the FFSL is also required to submit a burn plan to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s burn boss to ensure proper planning and supervision.

Fire wardens help assist with prescribed burns on private and state lands. Depending on the size of the burn, an individual may need to either file a burn permit or develop a burn plan required by Utah code.

United States Forest Service in Utah

There are five national forests in Utah: Ashley, Dixie, Fishlake, Manti-La Sal, and the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, and two that cross over the Utah-Idaho border: the Caribou-Targhee and Sawtooth National Forests. Four federal laws guide these management plans:

- The Multiple Use and Sustainable Yield Act of 1960

- National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969

- Forest Rangeland Resources Planning Act (RPA) of 1974

- National Forest Management Act (NFMA) of 1976

These four federal laws guide any action taken by the National Forest. Over the last year, the Dixie, Fishlake, and Manti-La Sal National forests have all proposed restoration projects to improve the health of these forests. Prescribed burns are one of the primary tools the FS intends to use going forward. In Fishlake, the FS proposes burning 40,000 acres per year but could be less or more depending on whether the environmental conditions are appropriate for that fire. In the Manti-La Sal National Forest, the FS proposes burning 48,000 acres per year. In the Dixie National Forest, the FS proposes burning 52,000 acres a year, increasing 13,000. The goal for each action plan is roughly the same.

Using LANDFIRE data, the FS service identified nearly a million acres in each forest that is either “moderately or very highly departed from their natural (historic) regime of vegetation characteristics” (United States Forest Service, 2021). Using controlled burns would allow the FS to reduce fuel sources and restore the forest’s natural ecosystem. There are alternatives, such as mechanical thinning and removal, but they are not cost-effective.

Before implementing these plans, the FS has to present the plans and their effects on the environment, public health and safety, animal habitats, and watersheds. Federal and state departments coordinate with different environmental agencies when preparing and executing prescribed burns to mitigate the effects on public health and safety. Another alternative is to utilize existing fires to burn through forest debris. However, circumstances can change, and wildfire managers can lose control over a fire.

In 2018, lightning started two fires; the Bald Mountain and Pole Creek fires were initially small enough that FS rangers allowed the fire to burn according to their plan. However, the wind conditions changed, and the fire grew out of control and caused 6,000 people to evacuate in Woodland Hills and Elk Ridge. The fire eventually burned more than 120,000 acres. The “facilitated learning analysis” published by the FS in 2019 concluded:

- There was no process to make risk-informed decision making

- There is no standardized terminology which leads to miscommunication and confusion

- There was a misunderstanding over how to read specific maps (United States Forest Service, 2019).

Bureau of Land Management

The BLM owns 22.7 million acres of Land in Utah and 245 million acres across all of the United States. Although there are several agencies within the DOI that manage wildland fires, the BLM accounts for 61% of the fire related workforce (Bureau of Land Management, 2021). Nationally, the BLM uses several resources for fire management including:

- 320 Engines

- 6 Veteran crews

- 13 Hotshot crews

- 150 Smoke jumpers

- 31 Tactical aircraft

- 25 Helicopters

- 21 Bulldozers

- 24 Water tenders

In Utah, there are 31 engines and two helicopters. The primary crew based out of Salt Lake City is the Bonneville Hotshots. There are three response levels that guide the agencies wildfire response. First, there are local field crews that provide the initial response, and depending on the size of the fire, the Geographic Area Coordinating Center (GACC) is contacted and mobilizes additional resources. The third level is the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC) which is used when a national response is needed to suppress a wildfire(Bureau of Land Management, 2021).

Research Design

The epistemic approach for this research is empiricism/positivism using a dataset from the FFSL containing more than 2,000 instances of wildfire occurrences from 2016-2021. Each fire is tracked by the FFSL using a unique incident number, the start date, and date the fire was put out, the incident name, longitude and latitude, general and specific cause, and the number of acres burned inside the state, and if the fire crossed state lines, how much acres it burned into another state.

The United States Geological Survey has datasets that cover a longer period. However, preliminary analysis of that data compared to the FFSL data set showed significant differences. The differences may be due to change in land ownership over the last 20 years, technological improvements to data collection, or changes in data collection methodology. Federal agencies deploy different methods to collect data on the size of wildfires, including: using GPS to walk, drive, or fly around the perimeter, hand sketches, infrared or digital images, or mixed methods. Therefore, this project was limited to state fire data over the last five years to get the best and most up-to-date analysis possible.

Findings

This study aimed to understand wildfire management policy in Utah and its effects across federal, state, and local jurisdictions. The FFSL shared their wildfire incidents report from 2016-2021. The report included whether the fire was caused by humans, natural, or undetermined causes. The data also included general causes such as accidental, arson, campfire, children, equipment, lightning, or other natural causes. On top of that, there is another category for specific causes that is more specific than general causes. For example, if the general cause of a fire was equipment, the specific cause may be the catalytic converter or a vehicle fire.

According to the data from the FFSL, there were about 8,460 fires and burned 1,167,424 acres throughout Utah. 398,619 acres burned on privately owned land, 333,560 acres burned on BLM land, and 297,793 on USFS land. Private land includes both lands owned by a private individual and a municipality. Of the fires that burned on privately owned land, only 9,495 acres were owned by a municipality. Unfortunately, it is not possible to separate privately owned land by the county and privately owned by an individual. In a 2020 review of federal land ownership by the Congressional Research Service found that the federal government owned 52,696,960 acres in the Utah.

| Ownership type | Acres owned | Acres burned | % acres burned |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLM | 22,787,881 | 333,560 | 1.50% |

| USFS | 8,192,893 | 297,793 | 3.60% |

| NPS | 2,097,860 | 807 | 0.04% |

| DOD | 78,420 | 22,641 | 28.87% |

| USFWS | 110,567 | 415 | 0.38% |

| Tribal | 2,045,000 | 12,799 | 0.63% |

| SITLA | 3,400,000 | 49,547 | 1.46% |

| Private | 11,400,000 | 398,619 | 3.50% |

| USP | 119,000 | 31,798 | 26.72% |

| FFSL | 1,045,000 | 2,164 | 0.21% |

| UDWR | 470,000 | 17,040 | 3.63% |

| Total | 52,696,960 | 1,167,241 | 2.22% |

Table 1.1 shows the differences land ownership and the number of acres burned over the last five years. The three primary areas where wildfires burned the most were private, BLM, and FS land. However, the DOD and Utah State Park (USP) saw the highest percentage of land acreage burned by wildfires at 28.87% and 26.72% respectively.

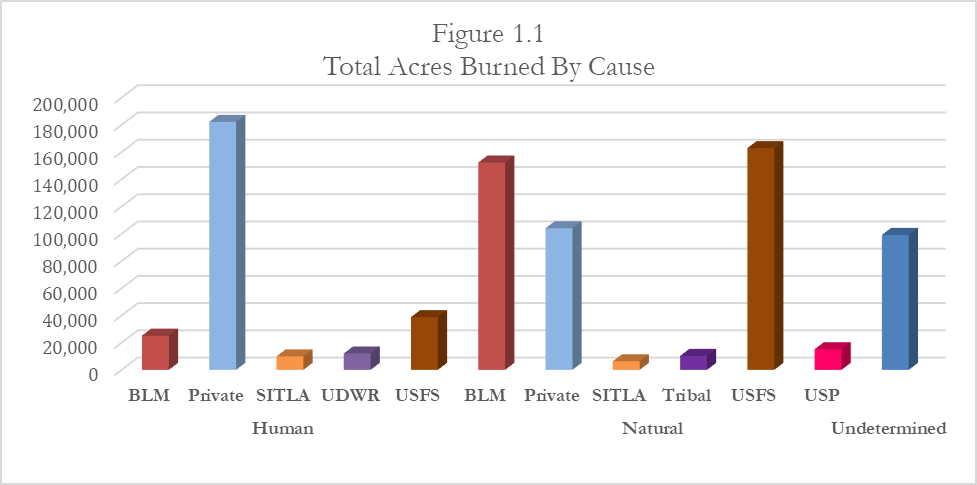

Figure 1.1 is an analysis of acres burned by human, natural, or undetermined causes. Fires from natural causes such as lightning accounted for more than 100,000 more acres burned than human caused fires. There is a third category of fires where the cause was undetermined on BLM, DOD, and private land, totaling 99,065 acres. The BLM oversees 42% of land in Utah compared to the 15% of land owned by the FS. However, the FS recorded several thousand more acres burned compared to the BLM.

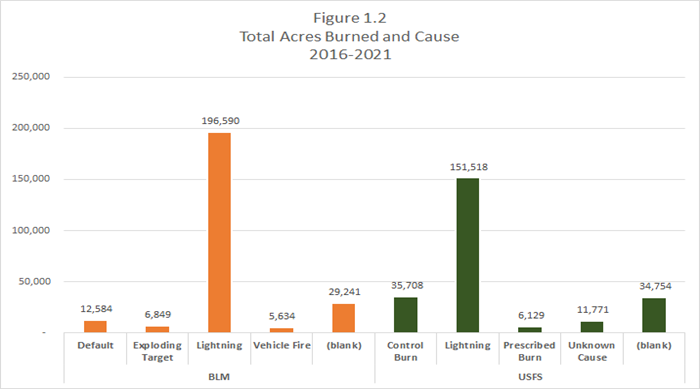

The data in Figure 1.2 shows the different wildfire causes on both BLM and USFS land. In both cases, fires caused by lightning resulted in more than 151,518 acres and 196,590 acres burned in the USFS and BLM, respectively. The second primary known cause of wildfire for the USFS were controlled burns and prescribed burns followed by unknown reasons. On BLM land, exploding targets and vehicle fires were the second. One of the challenges with this dataset were the number of recorded instances that were left blank. In figure 1.2, 29,241 acres were burned on BLM land by causes that were left blank and 34,754 acres on FS land that were left blank. This highlights one of the challenges of working with incomplete datasets.

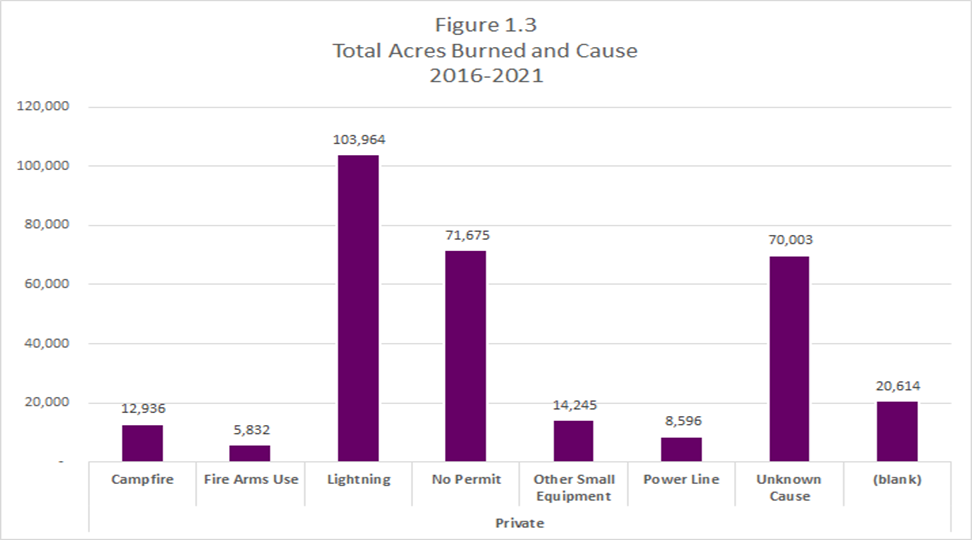

In figure 1.3, the picture is a little more diverse regarding the primary cause of wildfires. Private land can include both lands privately owned by an individual or by a municipality or county. Lightning is still the primary cause of wildfires burning over 103,964 acres, followed by fires started by individuals without a permit, unknown fires, small equipment fires, camping, power lines, and firm arm use.

Looking at the dataset as a whole, compared to BLM and FS land, campfires, power lines, and burns without a permit were primary causes of wildfire. More information is needed to better understand the fires that had unknown causes or were left blank, given that they resulted in more than 90,000 acres burned.

There were 297 recorded instances of prescribed burns over the last five years in reviewing the data. However, only 139 of those records included more than 0. Whether the 158 incidents reported as 0 acres burned were accurate is unclear. Of the 139 records, 42,724 acres resulted from prescribed burns on FS land, 975 acres on privately owned land, 400 acres burned on FWS land, 166 acres on BLM land, and 18 acres burned FFSL owned land. It’s expected that there will be more recorded instances of controlled burns as the state of Utah shifts from a suppression model to a more proactive approach to management.

Discussion

There is a lot of academic literature on wildfire management that promotes controlled burns to manage forests. There are many potential benefits to the use of prescribed burns, including restoring forests’ natural ecology, clearing out dead material, preventing excess forest debris from compounding, and becoming a catalyst for wildfire. From a management perspective, prescribed burns are much more cost-effective than other methods and are a proactive way to manage forests.

The data showed significant differences in the numbers of acres burned and causes of fire between federal, state, local, and private jurisdictions. One surprising result was how many more acres were burned on FS land than BLM land, which owns almost three times as much land as the FS. Lightning was the primary cause that burned the most acres on BLM, FS, and privately owned land. However, some of that is attributed to the controlled burns on FS land. In reality, as the use of prescribed burns increase, every agency will report a net increase in recorded instances of wildfire. The challenge will be communicating to the public that it’s a good thing where any fire was thought of negatively in the past.

There are a few arguments against the prescribed burning of forests. One of the primary concerns for many people is that the smoke produced from wildfires can negatively impact the communities downwind from a fire. Proponents of prescribed burning highlight the planning that goes into burns beforehand, including waiting until “the meteorological conditions are favorable, smoke production (fuel consumption) is less, atmospheric conditions support adequate smoke dispersion, and wind patterns allow smoke to move away from sensitive areas (e.g., populated areas, hospitals, schools, roadways) (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). However, there can be significant changes to the circumstance, and wildfires can get out of control. A prime example of this was the 2018 Bald Mountain and Pole Creek fires, which started small and eventually burned more than 120,000 acres.

This argument is more complicated because for prescribed burns to be more effective, significantly more acres are necessary to burn to make up for a century’s worth of mismanagement. A good example is the case of Yellowstone National Park, which from 1972-1987, 235 fires burned 33,759 acres, with only 15 reported to be larger than 100 acres (National Park Service, 2017). In 1988, Yellowstone had experienced a severe drought, and several uncontained fires burned 1.2 million acres across Wyoming (National Park Service, 2017). It’s possible that the drought conditions led to a more catastrophic situation than many anticipated, which poses a significant challenge to wildfire management in Utah.

Conclusion

This project aimed to understand how different agencies managed wildfires and the specific causes of wildland fire. The problems seen today are, in part, a result of the practices by forest and land managers throughout the 20th century. From the early 1900s to the 1960s, forest managers relied on a suppression policy that prevented forests from completing a natural cycle that had taken place for thousands of years. The result was a build-up of material in forests and more enormous and more catastrophic wildfires. Many researchers have concluded that prescribed burns may help reduce the build-up and make wildfires easier to manage. However, the risk of wildfires getting out of control, worsening drought conditions, and the health and safety impact of smoke make the argument that using prescribed burns is a less likely option. The research on this topic concluded that there are differences between wildfire causes and the capacity to manage wildfires between federal, state, and local departments. Overall, the future use of prescribed burns depends on a myriad of environmental and political factors that make the final determination on the matter inconclusive.

References

Bureau of Land Management. (2020). BLM releases final plan to construct and maintain up to 11,000 miles of fuel breaks in the Great Basin to combat wildfires. Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved from: https://www.blm.gov/press-release/blm-releases-final-plan-construct-and-maintain-11000-miles-fuel-breaks-great-basin

Congressional Research Service. (2021). Wildfire Management Funding: FY 2021 Appropriations. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11675

Dennison, P. E., Brewer, S. C., Arnold, J. D., & Moritz, M. A. (2014). Large wildfire trends in the western United States, 1984-2011. Geophysical Research Letters. Retrieved from: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/2014GL059576

Department of Interior. (2021, August 2021). Budget. Office of Wildfire. Retrieved from: https://www.doi.gov/wildlandfire/budget

Estep, K. (2021, October 4). The Peshtigo Fire. The Green Bay Press-Gazette.

Geller, W. (2020). 832,000 Acres: Maine’s 1825 Fire and Its Piscataquis Logging Aftermath. Mountain Explorations Publishing Company. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/319

Gorte, R. W. (2011, July 5). Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from: https://www.indianaffairs.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/public/pdf/idc-040964.pdf

Johnson, A. S., & Hale, P. E. (2002). The Historical Foundations of Prescribed Burning for Wildlife: A Southeastern Perspective. U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/19091

Lueck, D., & Bradshaw, K. M. (2011). Wildfire Policy: Law and Economies Perspectives.

MacEachern, A. (2020). The Miramichi Fire: A History. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

National Park Service. (2017). Yellowstone National Park, 1988: A 25th Anniversary Retrospective. National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/articles/wildland-fire-yell-1988-25th-anniv-retrospective.htm

North, M. P., Stephens, S. L., Collins, B. M., Agee, J. K., Aplet, G., Franklin, J. F., & Fule, P. Z. (2015). Reform Forest Management. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 349(6254), 1280-1281.

O’Leary, R., & Blomgren Bingham, L. (2009). The Collaborative Public Manager: New Ideas for the Twenty-first Century. Georgetown University Press.

PBS (Writer). (2015). The Big Burn (Season 27, Episode 4) [TV series episode]. In American Experience. PBS.

Stephens, S. L., & Ruth, L. W. (2005). Federal Forest Fire Policy in the United States. Ecological Society of America, 15(2), 532-542.

Tidwell, T. (2010). Big Burn Centennial Commemoration [Speech].

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, September 30). Comparative Assessment of the Impacts of Prescribed Fire Versus Wildfire (CAIF): A Case Study in the Western U.S. Wildland Fire Research. Retrieved from: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=352824

United States Forest Service. (2019). Pole Creek and Bald Mountain Fires Facilitated Learning Analysis. United States Forest Service. Pole Creek and Bald Mountain Fires Facilitated Learning Analysis

United States Forest Service. (2021, July 2). Homboldt-Toiyabe National Forest Forestwide Prescribed Fire Restoration Project. USDA Forest Service. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/nfs/11558/www/nepa/116195_FSPLT3_5644735.pdf

United States Forest Service. (2021, July 13). Forest-wide Prescribed Fire Restoration Project. United States Forest Service. Forest-wide Prescribed Fire Restoration Project

United States Forest Service. (2021, October 1). Dixie National Forest Prescribed Fire Restoration Project Proposed Action for Scoping. USDA Forest Service. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/nfs/11558/www/nepa/116786_FSPLT3_5672609.pdf

U.S. Drought Monitor. (2021). Utah. U.S. Drought Monitor. Retrieved from: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?UT

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Fire on Wildlife Refuges. US Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.fws.gov/fire/outreach/Fire_on_NWRs.pdf

Utah Department of Natural Resources. (2021). Fire Management 2021 Program Guide. Fire Management Program Guide. https://ffsl.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Combined-2021-Fire-Management-Program-Guide-Safety-Handbook-Issuu.pdf

Williams, G. W. (2005, April 0). The USDA Forest Service: The first century. United States Forest Service — Our History. Retrieved from: https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/2015/06/The_USDA_Forest_Service_TheFirstCentury.pdf