1

Identifying and Explaining the Gap Between Consumer Perceptions and Purchases of Products

Charlotte Serage; Sydney Metcalf; Joseph Erickson; and Meagan Wilson

Over the past few decades, numerous studies have confirmed that consumers are willing to pay more for certain products that are labeled as sustainably produced (Biswas & Roy, 2016; Wei et al., 2018). However, why consumers are willing to pay more and for what products remain ill-defined in academia. Understanding this consumer behavior requires an analysis of our socially constructed perspective of sustainability—what the word “sustainability” means to us as consumers, what symbols and language we associate with sustainability, and by whom our understanding of sustainability is influenced. Thus, this study fills a gap in the research by examining which underlying values drive sustainable purchases. By understanding the question of “sustainability-oriented motivation,” firms can better market green products.

This study takes a combined qualitative interpretive and quantitative empirical approach to data collection, allowing us to gather deeper, more complex responses. To analyze what consumer motivations exist for choosing products certified as sustainable, we conducted in-depth interviews with eight U.S. consumers between the ages of 18-30, examining their purchasing behaviors generally and also investigating a specific consumer product: chocolate. By pinpointing a specific consumer good, we can analyze consumer attitudes toward sustainability as a whole and their experience with a highly specific purchasing decision. Our goal was to obtain an understanding of sustainability motivations based on a holistic picture of the consumer created by their stated perception of sustainability, prioritization of product features, shopping influences, and information sources. We found that these factors impacted general purchases to take sustainability into account; however, they were not strong enough to place sustainability at the forefront of purchasing behavior. Concerning chocolate purchases, a lack of understanding about the sustainability of chocolate production currently appears to limit any change in behavior.

Literature Review

For the purposes of this study, we use Dolan’s (2002, pp. 170) concept of sustainable consumption as our definition of sustainability for consumers, i.e., the habits and discourse that seek “to present a solution to the [social and] ecological problems associated with industrial economic production.” There is an abundance of literature concerning different branches of sustainability, primarily environmental and social sustainability. Recanati et al. (2018) outline the environmental impacts and risks of the chocolate supply chain, highlighting global warming, ozone layer depletion, and high energy requirements as negative externalities of unsustainable chocolate production, but they also note there are ways chocolate is sustainably produced for the environment. Additionally, chocolate industry giants have been criticized for their complicity in the poor working conditions throughout the cocoa supply chain. According to Deam (2020, pp. 279), the latest reports on the worst forms of child labor in West Africa indicate “there are now an estimated two million children engaged in dangerous child labor.” Thus, the production of chocolate involves both grave environmental and social risks.

We have identified contradictory findings both between academics and the realities of the marketplace. Most scholars agree that consumers are willing to purchase sustainable products but disagree on the consumers’ motivations. One study found that consumers purchased eco-friendly products based on the following motivators: perceived consumer effectiveness, consumer knowledge, laws and regulation, and promotional tools (Kianpour et al., 2014). This study assumes consumers are usually well informed about the benefits and drawbacks of their purchases.

Quintelier (2014, p. 342) argues that political consumption—i.e., basing shopping motivations on political reasons such as “preserving the environment, developing a sustainable economy, or using boycotts as political pressure—alongside social reasons such as reducing child labor” broadly drives consumption decisions. These motivations further stem from the consumer’s “Big 5” personal structure, i.e., openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Davies & Gutsche (2016, p. 1326) argue that consumers are increasingly motivated to purchase ethical products, “despite having little interest or understanding of the ethics” behind these purchases. These studies may indicate that sustainable consumption is done without a thorough understanding of its implications but rather out of factors, particularly social obligation. This poses the question of influence: from what sources are consumers influenced to make purchases and how does that impact their view of sustainable shopping?

However, certain studies oppose the claim that sustainable shopping is growing. Findings by Bhaskaran et al. (2006, p. 677) show how the demand for foods that are produced under environmentally sustainable standards “has been slow to take off because customers do not perceive these products as offering any special benefits.” Moreover, customers do not trust organizations’ claims about sustainability, find sustainability products too expensive in comparison to traditional products, and “claim that the use of different terminologies such as organic, green, and environmentally friendly in promoting food products is confusing” (ibid). The effectiveness of sustainability labels is therefore put into question.

Thus, despite ample information online about general sustainability and chocolate-specific sustainability, there is little agreement as to whether this information influences consumer behavior. This study investigates such contradictions by interviewing consumers about their attitudes and prioritization of sustainability as a whole. Specifically concerning chocolate, this analysis expands upon research from García-Herrero et al. (2019), which identifies gaps between consumer perceptions of the chocolate value chain and realities in their purchases, as well as Silva et al.’s (2019) study, which analyzed the impact of sustainability labels on the purchase intention of chocolate consumers. Our study also corroborates Prakash et al.’s (2019) view that both altruistic and egoistic values may influence consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward eco-friendly products.

Research Design

Our study’s research design blurs the line between empiricist and interpretivist approaches, as well as qualitative and quantitative research. It is qualitative because the data collection method used was interview format. It is quantitative because of the method in which we put all responses into a spreadsheet and compared all interviews to one another and across various demographic markers. By interpretivist, we mean our study took observations and drew a conclusion based on inference and interpretation. It maintained an empiricist aspect because we aggregated all the responses and drew conclusions from that information as well.

We chose to do eight interviews with consumers between the ages of 18-30. We then entered all answers and results in a Google Form and its associated datasheet to better be able to codify and compare the responses across the various interviews. The method allowed us to benefit from both the complex answers that stem from qualitative interviews, while also leaving room to empirically view and analyze the gathered information.

We used non-random, convenience sampling. After testing our initial interview questions in pilot interviews, we settled on three main question groups. The first was generic demographic questions. The second focused on sustainability within consumer choices more broadly. The third focused more specifically on consumer preferences regarding the chocolate products(see Appendix A for full list of questions).

The age group of 18-30 was chosen because this group tends to be consumers who are both the key decision-makers in their households as well as price-sensitive with most purchases. Chocolate was chosen as our specific product to analyze in this study for multiple reasons. As García-Herrero et al. (2019, p. 177) notes, chocolate is “a highly processed product widely consumed in developed countries (…) despite the environmental, economic, and social impacts of its production.” In other words, the supply chain for chocolate products is considered controversial, but chocolate remains ubiquitous in the marketplace. Moreover, there is usually only a marginal difference in price between the most premium chocolate brands and the most inexpensive brands. Thus, price elasticity of demand was not expected to significantly alter the priorities of a price-sensitive consumer group.

Our quantitative empirical analysis consists of analyzing the responses and determining why perceptions of sustainable production influence young adult consumers’ general and chocolate-specific purchasing decisions. Specifically, we looked at the frequency of various categorical data, such as: top purchasing influencers, top chocolate purchasing influencers, and what types of information is most used when making general and chocolate purchases. We used demographic information to gauge differences in perception of sustainability and consequent purchasing behavior.

Findings and Discussion

“First Thoughts” About Sustainable Products

We began by asking each of our respondents, “What products come to mind when you think about sustainable purchases?” The responses covered many different product types. Some respondents thought of individual products such as bamboo toothbrushes, recyclable bottles, shampoo bars, reusable bags, ocean bracelets, etc. Some other responses focused on industries as a whole by discussing packaging practices, the food industry, and ethical brands in general. When asked to expand on their response that food came to mind, one respondent described feasibility as one reason it was at the forefront of their mind:

Food comes to mind. The other thing I think of is clothing. Probably those two would be first. I think that a lot of the pollution comes from food and [it] is also one of the easiest to prevent. It is hard to not mine nickel for phones, but it is relatively easy to change farming practices. A lot easier for those people to comply with sustainability. With clothing I honestly think that a lot of the reason for that is all the documentaries on it and how unsustainable it is. I think there are things to be done with technological practices, but it is a lot easier to change agricultural practices.

These two major groupings of responses show the tension between individual and institutional responsibility. It has become more common for the individual to feel and receive responsibility for their actions and the subsequent effects they have on the environment. While this is common, there are groups and academics who argue the onus still remains with the institutions more than the individual (Fahlquist, 2009). These differences in responses suggest that many individuals think about sustainability. The main difference is whether they pin sustainability responsibilities on themselves or larger institutions, at least as an initial response. Another individual mentioned thinking about bamboo toothbrushes because she had seen a documentary, which had said “that every toothbrush I had ever used was still on the planet.” This response points toward a much more individual responsibility mindset.

Decision Rankings: General Purchases vs. Chocolate Purchases

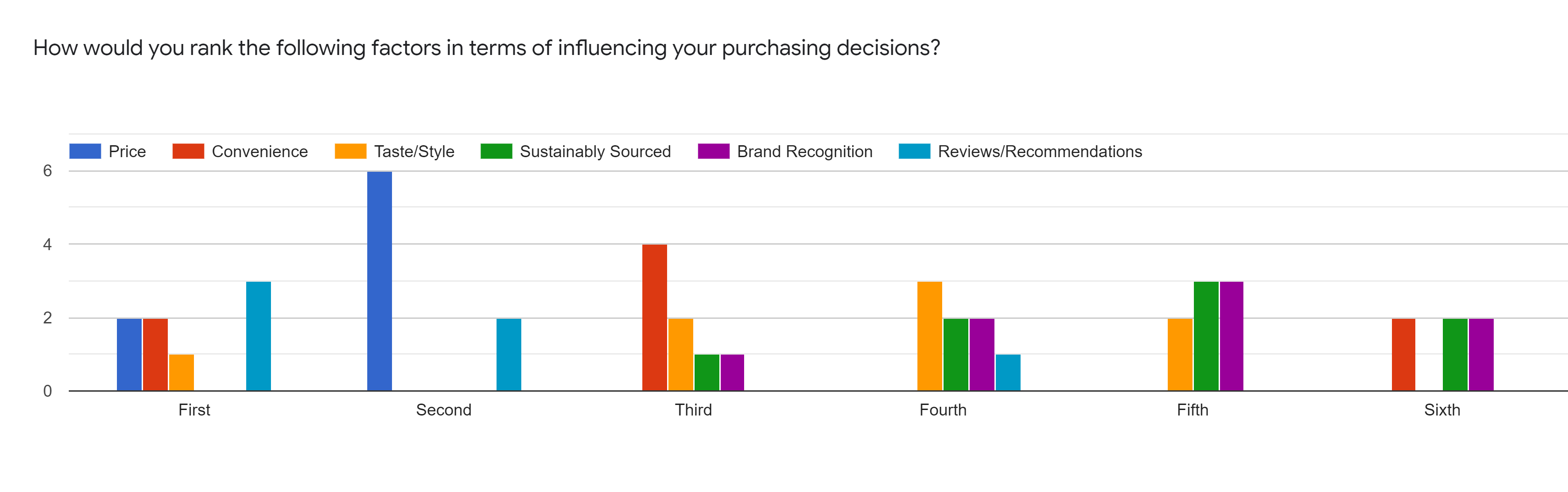

To better understand why and to what extent consumers were willing to pay more for sustainability, we asked respondents to rank how they prioritized certain factors when shopping. The tables below represent how respondents ranked the following factors as influential in their purchasing decisions:

- Price

- Convenience

- Taste/style

- Sustainable sourcing

- Brand recognition

- Reviews/recommendations

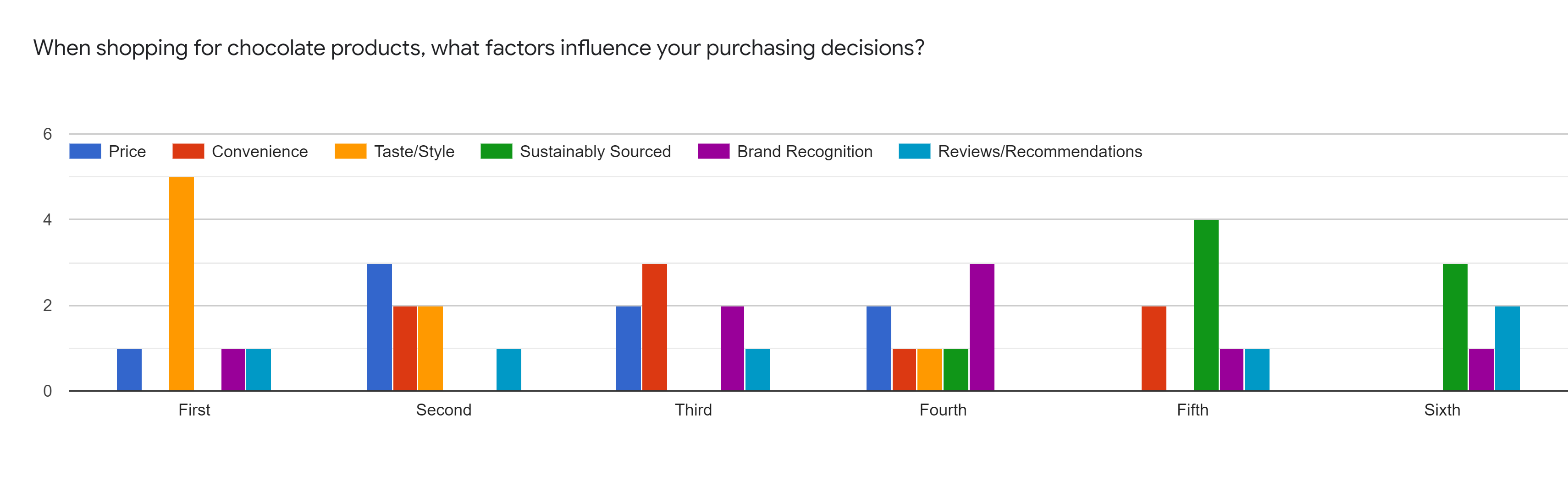

Figure 1 shows the results of our queries concerning general purchases. The bars show the number of times a factor was ordered in a certain ranking by the respondents (e.g., brand recognition was listed as the fourth-most important factor by two respondents, so the purple bar at “Fourth” is valued at 2). Figure 2 displays the same responses but specific to chocolate purchases.

Among all respondents, price was the mode for the top three most important factors to consider when making decisions for general purchases as all eight participants ranked it first or second. Convenience ranked second, and reviews/recommendations ranked third. This somewhat contradicts the literature, e.g., Quintelier (2014), that suggests consumers are willing to prioritize sustainability over price, largely motivated to do so based on political motivations such as protecting the environment. Our respondents were generally familiar with these concerns, citing awareness of finite resources and waste from packaging as motivators for buying sustainably. However, Bhaskaran’s (2006) claim is arguably reflected instead: the price of sustainable products remains a barrier to being chosen over traditional products. Interestingly, the only respondent who placed “sustainably sourced” in the top three (ranking it third) was the highest earner with an annual income of $110,000. However, “price” was still ranked above “sustainably sourced” in their response.

Taste was the most important factor for chocolate purchases, followed by price, with convenience ranking third. For these respondents, who are generally perceived as price-sensitive, price was not as important as the taste of the chocolate. Sustainable sourcing was unanimously ranked in the bottom three factors, with seven out of eight respondents ranking this last or second-to-last. Compared to general sustainability attitudes, chocolate-specific responses had far poorer outcomes. From our responses, it appears the sustainability of chocolate is rarely, if ever, taken into account at the time of purchase despite having a socially and environmentally controversial supply chain. This gap raises questions around the difference in dialogue between general and chocolate-specific sustainability.

Sustainability Certifications and Labels: General Purchases vs. Chocolate Purchases

Interviewees were asked about sustainability to better assess their understanding and interpretations regarding sustainability labels. By asking what they believe the labels mean, we can identify how the perception of the label correlates with future sustainability questions. Five out of eight respondents spoke positively of the labels. They described them as better for the environment and often tied an ethical attribute to these certifications. One respondent was more skeptical and the other two did not have a predisposed view on these kinds of labels. Overall, our eight respondents felt these labels sought to promote something positive regarding the ethical production of the goods. Some were dubious as to whether they are effective in signaling the best form of production.

The respondents were then asked if these kinds of sustainability labels or certifications affect their general purchasing or chocolate purchasing decisions. Half of respondents stated that it did have a bearing on their general purchasing decisions, but some attached qualifiers about price. For example, one individual responded, “All else equal, yes. But considering the prices are usually different, it usually isn’t enough to sway me.” The same individual stated that sustainability labels signal the organization is considering their negative externalities of production. So while labels seemed like a positive factor, it did not produce a strong enough effect to change the respondent’s purchasing priorities. This is congruent with literature showing that labels matter, but the product is most important (Silva et al., 2017).

Similarly, another respondent first shared that sustainability labels mean “that a company has ethics and is going out of their way to make a difference and not just worry about their bottom line. In this day and age that’s as important.” Then immediately being asked if labels affect their purchases, they responded:

When I’m already close to buying something, it might move the needle. I don’t think it’s the first thing I’m going to look for, but if I’m on the fence and I see something like that, then I can feel better about the purchase and anything that makes me feel less guilty about spending money on something, the better!

They responded affirmatively that sustainability influences their purchases, but sustainability labels are not as influential as other factors. This demonstrates that they do participate in political consumption, but sustainability certifications may not be what strongly motivates someone to politically consume a product (Quintelier, 2014).

Our final question regarding labels asked respondents if they noticed sustainability labels on chocolate bars. All but one respondent stated they do not notice sustainability labels on chocolate purchases. This respondent attributed it to a regional factor, stating “…in NYC I actually have because they make the labels really big. There is a lot of pride in that.” Individual demographics and sustainability labels seem to have little to no correlation with chocolate purchasing. A more important factor, may be the market or culture in which one exists.

Trusted Sources of Information: General Purchases vs. Chocolate Purchases

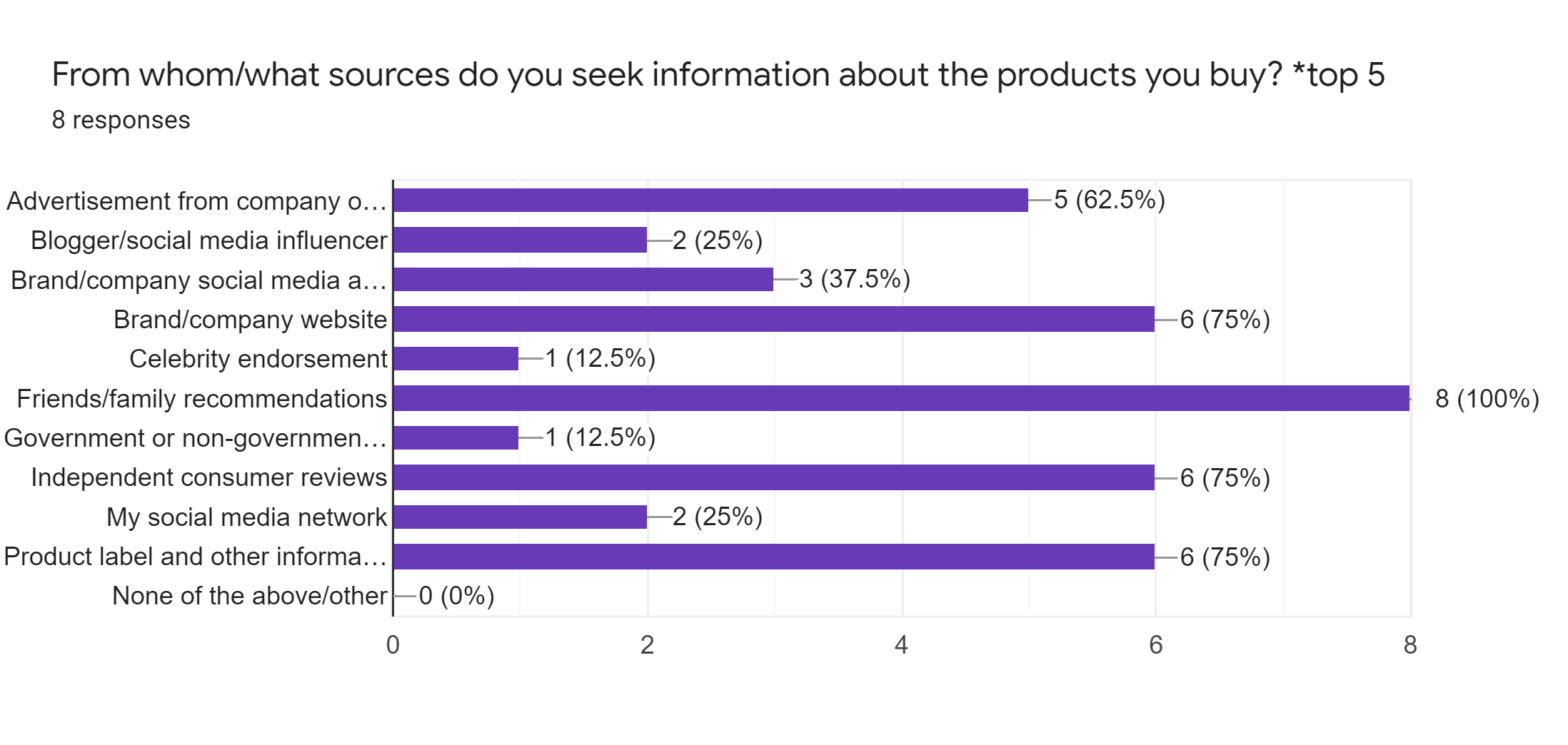

In order to understand how the respondents’ consumption patterns were influenced by their daily surroundings, we asked them to list the top five sources from which they seek information about the products they consider for purchase. The options available to choose from were:

- Advertisement from company or brand

- Blogger/social media influencer

- Brand/company social media accounts

- Brand/company website

- Celebrity endorsement

- Friends/family recommendations

- Government or non-government expert organizations

- Independent consumer reviews

- [Their] social media network

- Product label and other information shown on packaging or brand website

- None of the above/other

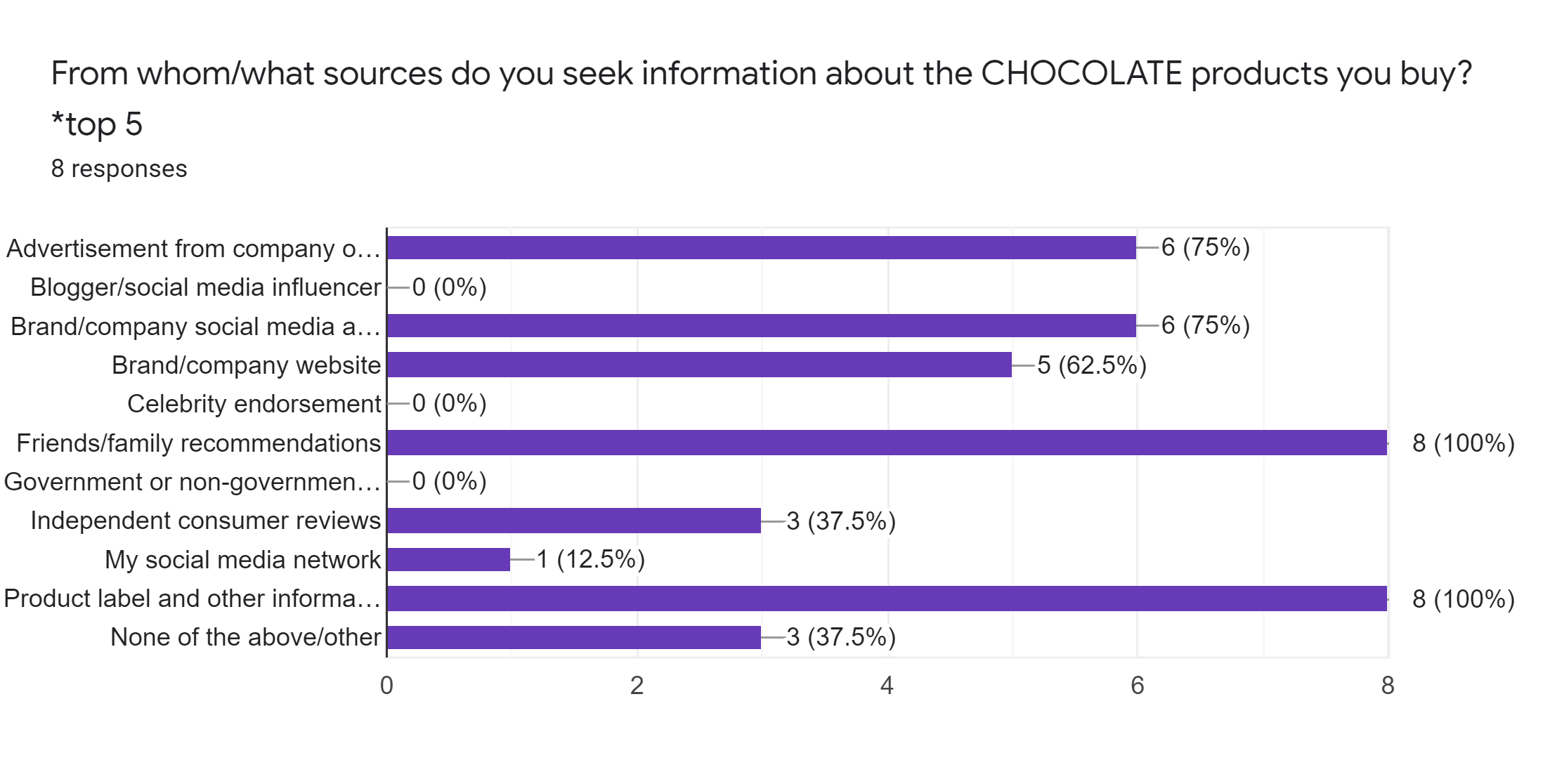

The figures below represent the top five sources from which respondents said they seek information about the products they buy. Figure 3 displays the results of general purchases, while Figure 4 displays responses about chocolate-specific purchases.

All eight of the respondents valued friends/family recommendations in regard to their general purchases. Additionally, 75% of respondents also valued brand/company websites, independent consumer reviews and product labels and other information shown on packaging. Advertisement from company or brand came in third place with 62.5% of respondents marking it as a source they use for gathering information on products.

All eight respondents once again valued friends/family recommendations when it came to chocolate-specific purchases. The respondents also unanimously valued product labels and other information shown on packaging. Six respondents valued advertisement from company or brand and brand/company social media accounts. The third-most valued source selected by participants was brand/company website.

When it comes to general purchases, respondents’ choices were more scattered across all of the options available for gathering information on a product. Responses became far more uniform once the question became more specifically about chocolate products, with all respondents disregarding blogger/social media influencers, celebrity endorsements and government or non-government expert organizations.

From these results it can be gathered that participants in these interviews place high value on the recommendations of friends and family. This could likely mean that if their friends and family place high value on sustainably sourced products, they will begin to do so as well. Secondary to that comes gathering information on a product from the company itself. This could mean that if companies released more sustainability-related information about their products, it could result in an increased consumer drive to purchase sustainably sourced products. Having trusted sources like friends, families and companies talk more about sustainability could positively alter the value placed upon it as a factor considered when purchasing an item like chocolate.

Labor Conditions or Environmental Standards: General Purchases vs. Chocolate Purchases

When diving into the perceptions of sustainable sourcing, there were mixed responses on what was most important between environmental sustainability and labor conditions. When asked, “What would you say is the difference between a product with a sustainability label/certification and one that does not have one?” only one response had an ethically sourced consideration. When speaking about sustainable sourcing, according to this study, most individuals initially thought of environmental factors, specifically the environmental impacts that are involved with the production of the good, and what effects the good and its packaging would have on the planet after its disposal.

Respondents were then asked, “Would you rather know that your purchases have been produced/manufactured under sustainable labor conditions (e.g., guarantees human rights in the communities where the product is sourced/manufactured) or sustainable environmental standards?” 75% of respondents stated that labor conditions were more important to them. The one respondent that chose environmental sustainability over labor conditions stated:

I would say environmental, it’s an important thing to fix that first over fair labor laws. Both really important but there are enough companies already aware of what they should be doing in terms of sustainable labor– fewer options on environmentally sustainable things. If we don’t have an environment then there’s nowhere for people to live happily.

Given that the initial reaction of nearly all respondents was to consider sustainable sourcing as strictly environmental, this response was more expected. When faced with human rights versus the environment, individuals surveyed would prefer that they know their products come from a company that treats their employees well, but their immediate thoughts go to the environment. With further research, it could be identified if this is due to the prevalence of environmental initiatives and labor issues that do not have as much visibility or possibly the presumption that companies already provide ethical employment.

When asked the same question in regard to chocolate products more specifically, one respondent stated, “I never thought of chocolate as being produced under unsustainable labor conditions. I would probably pay more attention to environmental certifications on a label.” This aligns with the theory that labor conditions may not have as much visibility as environmental sustainability. Two of the eight respondents answered that they favored labor conditions over environmental impacts. Three chose environmental sustainability as what they would prefer, and the remaining three offered with mixed responses. The 37.5% of respondents that had mixed responses, felt that both sides should be fulfilled. With further research, additional questions about awareness could be asked to provide more in-depth detail about why each individual feels strongly about sustainable sourcing and why opinions change when it comes to specific products.

Study Limitations and Ethical Considerations

The goal of this study was to gather a more in-depth view of the decision-making processes of a few individuals. We opted to use a convenience sampling to gather participants. Therein may exist an ethical issue of multiple roles considering our primary interviewees were close acquaintances or friends as opposed to randomly selected strangers. We were thus researchers but simultaneously friends or colleagues, potentially resulting in differences to the kind of answer a respondent offered. They may have felt comfortable giving an honest answer about their shopping habits to a friend, i.e., an interviewee may wish to sound more socially responsible upon realizing the researcher is asking about sustainability and personal habits. This compounds the issue the study wishes to confront about sustainable shopping motivations—true consumer feelings and motivations about the subject.

Anticipating that participants may have felt pressure to answer questions in the way they felt that they “should” rather than giving a more realistic, honest perspective on the matter, the order of questions was carefully taken into consideration. The questions began with more general wording about consumer decisions, then later became more specifically about sustainability and chocolate products (see Appendix A). This made it easier to gauge if sustainability was truly a priority of the participant when pitted against other influences to their decisions, before the participant became more fully aware that sustainability was a target subject of the study.

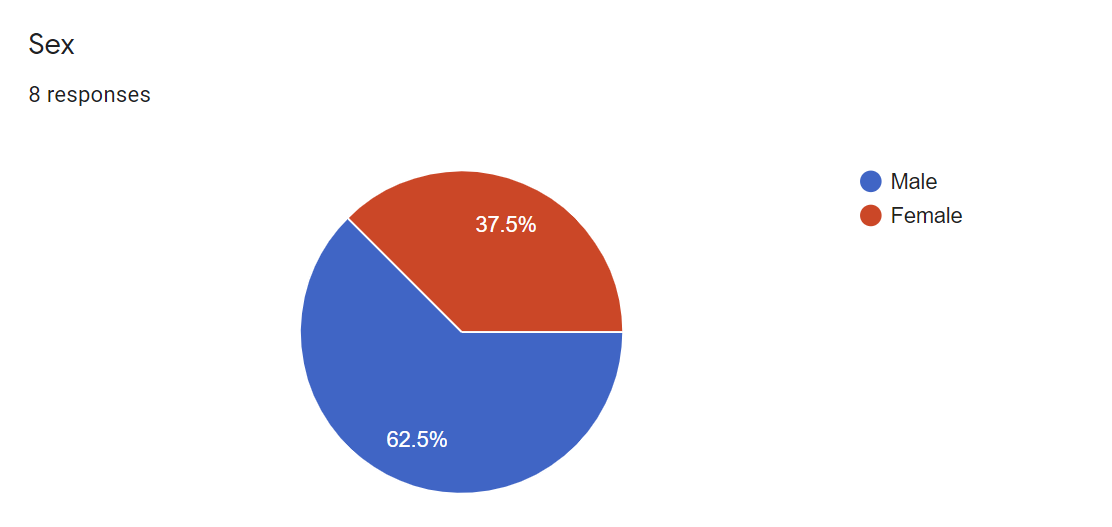

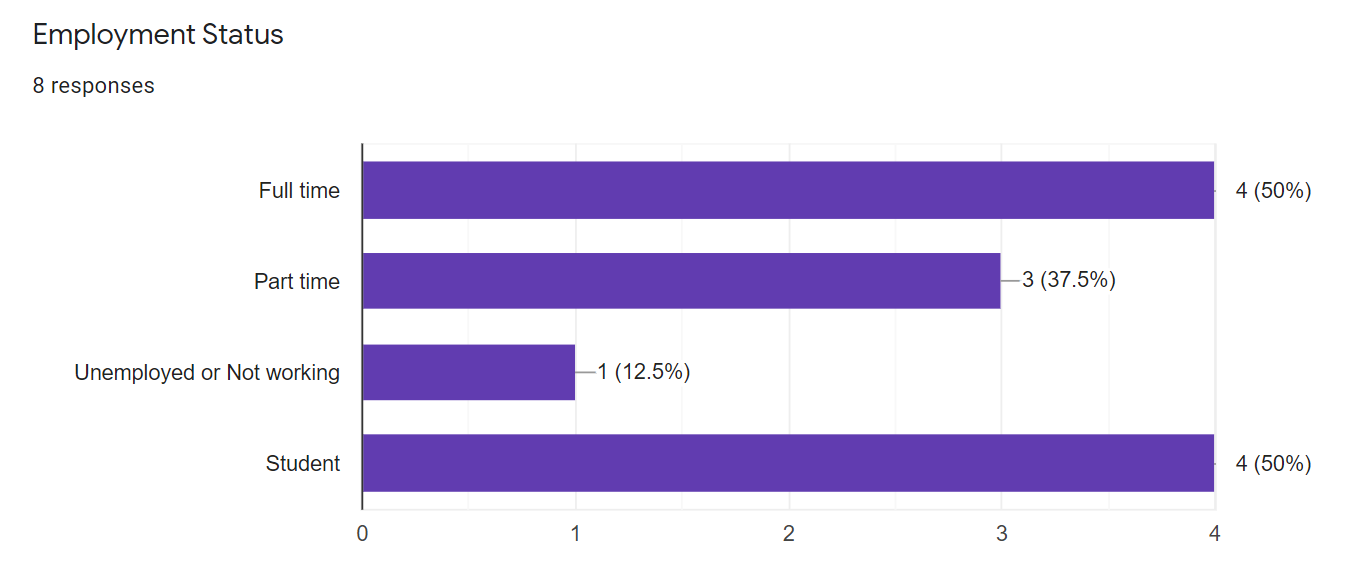

Diversity in the survey population is an additional limitation of note. The sample is fairly diverse in terms of income and employment status, but there is also a majority of male participants (see Appendix B). Moreover, our sample population is entirely white. Thus, the perspectives analyzed in this study are particularly limited in terms of racial diversity.

Conclusion

This microstudy was intended to explore why and how consumers make general purchasing decisions, and more specifically, their feelings around and understanding of sustainability within the chocolate industry. We found a gap between the positive feelings and associations respondents have with sustainability then translating into the actual prioritization of purchasing sustainable chocolate products. We additionally found that respondents typically associated sustainability with environmental issues, rather than as an issue of labor rights. These findings indicated a general lack of awareness about sustainability practices, or the lack thereof, within the chocolate industry.

It was found that other factors, like price, ranked higher when making general purchasing decisions, despite feelings about sustainability being strongly expressed by respondents. This was especially true when asked specifically about chocolate purchases, where the respondents leaned more towards factors of price, taste and convenience. Sustainability in chocolate purchases was more of a “feel-good” afterthought, if considered at all. Respondents generally placed high value upon the recommendations of family and friends, and upon seeking information about a product from the company itself. This indicated that having trusted sources talk more about sustainability, may increase the influence it has as a factor considered when making purchasing decisions. Although it was clear that respondents are increasingly beginning to feel more of a personal responsibility for purchasing sustainably sourced products in today’s social environment, there is still further need for education on what this means and what it looks like specifically within the chocolate industry.

References

Bhaskaran, S., Polonsky, M., Cary, J., & Fernandez, S. (2006). Environmentally sustainable food production and marketing. British Food Journal, 108(8), 677–690.

Biswas, A., & Roy, M. (2016). A Study of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Products. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 211–215.

Davies, I. A., & Gutsche, S. (2016). Consumer motivations for mainstream “ethical” consumption. European Journal of Marketing, 50(7/8), 1326–1347.

Deam, A. W. (2020). Children, Chocolate, And Profits: A Policy-Oriented Analysis Of Child Labor And The Chocolate Industry Giants. Intercultural Human Rights Law Review, 15(1), 257–284.

Dolan, P. (2002). The Sustainability of “Sustainable Consumption.” Journal of Macromarketing, 22(2), 170–181.

Fahlquist, J. N. (2009). Moral Responsibility for Environmental Problems—Individual or Institutional? Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 22(2), 109–124.

García-Herrero, L., Menna, F. D., & Vittuari, M. (2019). Sustainability concerns and practices in the chocolate life cycle: Integrating consumers’ perceptions and experts’ knowledge. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 20, 117–127.

Kianpour, K., Anvari, R., Jusoh, A., & Fauzi Othman, M. (2014). Important motivators for buying green products. Intangible Capital, 10(5), 873–893.

Prakash, G., Choudhary, S., Kumar, A., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Khan, S. A. R., & Panda, T. K. (2019). Do altruistic and egoistic values influence consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions towards eco-friendly packaged products? An empirical investigation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 163–169.

Quintelier, E. (2014). The influence of the Big 5 personality traits on young people’s political consumer behavior. Young Consumers, 15(4), 342–352.

Recanati, F., Marveggio, D., & Dotelli, G. (2018). From beans to bar: A life cycle assessment towards sustainable chocolate supply chain. Science of The Total Environment, 613–614, 1013–1023.

Silva, A. R. D. A., Bioto, A. S., Efraim, P., & Queiroz, G. D. C. (2017). Impact of sustainability labeling in the perception of sensory quality and purchase intention of chocolate consumers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 141, 11–21.

Wei, S., Ang, T., & Jancenelle, V. E. (2018). Willingness to pay more for green products: The interplay of consumer characteristics and customer participation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 45, 230–238.

Appendices

Appendix A: Interview Questions

A.1. Background Questions:

- Please state your age.

- Please select which best identifies your gender.

- What is your ethnicity?

- What education level have you attained?

- What is your employment status?

- What is your geographic location of residence?

- Select your marital status.

- What is roughly your annual income?

- Are you the primary purchasing decision-maker in your residence?

A.2. Study Questions:

- How would you rank the following factors in terms of influencing your purchasing decisions?

- Price, Convenience

- Taste/Style

- Sustainably Sourced

- Brand Recognition

- Reviews/Recommendations

- (If they ranked Sustainability in top 3): Why do you think sustainability is important?

- (If they ranked Sustainability in bottom 3): Why did you choose your top answer(s)?

- What would you say is the difference between a product with a sustainability label/certification and one that does not have one?

- Is a sustainable label/certification something that influences your purchasing decisions? If so, why?

- From what sources do you seek information about the products you buy? (choose top 5):

- Advertisement from company or brand

- Blogger/social media influencer

- Brand/company social media accounts

- Brand/company website

- Celebrity endorsement

- Friends/family recommendations

- Government or non-government expert organizations

- Independent consumer reviews

- My social media network

- Product label and other information shown on packaging or brand website

- None of the above/other

- Would you rather know that your purchases have been produced/manufactured under sustainable labor conditions (e.g., guarantees human rights in the communities where the product is sourced/manufactured) or sustainable environmental standards?

- What products come to mind when you think about sustainable purchases?

- When shopping for chocolate products, what factors influence your purchasing decisions? (Price, Convenience, Taste/flavor, Sustainably Sourced, Brand Recognition, Reviews/Recommendations) (Explain your choices)…

- Do you notice sustainability labels/certifications on chocolate products?

- If yes, which ones?

- If yes, does a sustainable label/certification influence your chocolate purchases? If so, why?

- From what sources do you seek information about the chocolate products you buy? (choose top 5):

- Advertisement from company or brand

- Blogger/social media influencer

- Brand/company social media accounts

- Brand/company website

- Celebrity endorsement

- Friends/family recommendations

- Government or non-government expert organizations

- Independent consumer reviews

- My social media network

- Product label and other information shown on packaging or brand website

- None of the above/other

- Would you rather know that your chocolate purchases have been produced under sustainable labor conditions or sustainable environmental standards?

Appendix B: Interviewee Demographics

B.1. Sex:

B.2. Physical Location:

- Salt Lake City, Utah (4 respondents)

- Logan, Utah (1 respondent)

- Easley, South Carolina (1 respondent)

- Powdersville, South Carolina (1 respondent)

- New York City, New York (1 respondent)

B.3. Annual Income (USD) and Employment Status*:

- 12,000

- 18,000

- 20,000

- 40,000

- 48,000

- 53,000

- 75,000

- 110,000

*Some respondents were both students and employed or unemployed

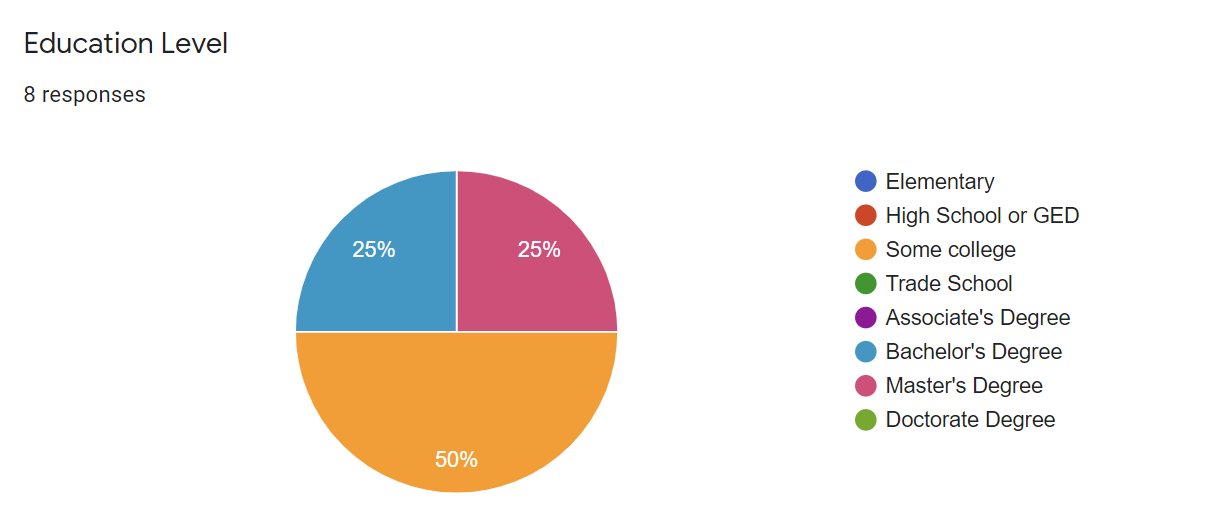

B.4. Education Level: