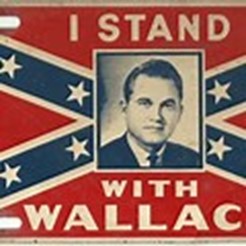

The images[1] above illustrate ongoing obstacles to African American inclusion in post-Civil Rights America. In 2014, news articles reported on “Segregation now…: Sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education [1954], the schools in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, show how separate and unequal education is coming back” (Hannah-Jones 2014). “Segregation now…” refers to pro-apartheid Alabama governor and 1968 presidential candidate George Wallace (1919-1998). His 1963 inaugural speech famously declared “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Likewise, Wallace’s 1968 presidential campaign was explicitly white supremacist and segregationist. These messages are visible in his 1960s Confederate-themed campaign materials (left image above).

Today, it is often forgotten that Wallace’s years as Alabama governor were mostly in the 1970s and 80s, not just the 1960s.[2] Like many other politicians who had opposed black civil rights during the 1940s-60s (e.g., South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond), he successfully maintained political viability in the post-Civil Rights era by adopting colorblindness (see Chapter 9). But beyond race-neutral rhetoric, Wallace and his southern and northern supporters clearly formed part of the white resistance (1970s-80s) to de facto racial equality (Carter 2000; Marx 1997). How does Wallace’s political career—bridging “then” and “now”—illustrate both breaks and continuities with the explicitly racist past? How have social structures created by white supremacy—black ghettos, segregated and unequal education, poverty, criminalization, poor health—endured into the present, continuing to block genuine, versus merely rhetorical, inclusion in the world’s wealthiest nation?

Chapter 10 Learning Objectives

10.1 White Normativity vs. Individual Prejudice

- Define white normativity

- Explain how social institutions without prejudiced individuals can nevertheless show bias against nonwhites

10.2 Understanding White Normativity

- Describe how American society has often treated whiteness as “normal,” like being right-handed

- Understand white normativity in higher education settings such as law school

10.3 De Facto Residential Segregation

- Define de facto residential segregation

- Understand that post-Civil Rights America remained a society of extreme black-white housing segregation

10.4 De Facto Educational Segregation

- Define de facto educational segregation

- Define the racial achievement gap

- Understand that post-Civil Rights America remained a society of racially separate and unequal education

Chapter 10 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

individual prejudice: aka psychological racism. Personal attitudes of white supremacy or anti-color bias. Prejudice literally means “pre-judgment,” as in judging people before meeting them.

white normativity: aka systemic racism. Institutional normalization of whiteness. This is a feature of social institutions treating white perspectives as the norm (standard, default), while treating nonwhite perspectives as deviant or problematic. Such institutions may be schools, real estate agencies, employers, police departments, hospitals, etc.

de facto residential segregation: racially separate neighborhoods in practice, not by law

de facto educational segregation: racially separate schools or classrooms in practice, not by law

racial achievement gap: racial-ethnic group disparities in educational outcomes. E.g., test scores, grade point averages, and/or high school and college completion rates.

the schools-to-prison pipeline: an all-too-common trajectory in the lives of young, black males: after dropping out of impoverished, low-quality public schools, they are soon incarcerated.

10.1 White Normativity vs. Individual Prejudice

The purpose of Chapters 9-11 is to explain why most sociologists today see race as a social problem that is largely ongoing, not overcome. This includes not only the U.S., but many societies with long histories of racialized inequality (e.g., South Africa, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico). Chapter 10 adds to this explanation, discussing two present-day obstacles to genuine (versus rhetorical) African American inclusion: (1) white normativity and (2) de facto segregation.

All U.S. nonwhite and white-ethnic groups have experienced significant social, political, and economic exclusion. However, none has to the extent of African Americans (APAN:II; Bell 2004; Harvey 2007). Indeed, in contemporary demographic analysis of life chances of racial-ethnic groups (e.g., Mexican Americans), the African American group often serves as a baseline (comparison) measure of extreme exclusion (Telles & Ortiz 2008:264). American society is formally (de jure) color-blind, but the de facto reality is that blackness continues to matter a great deal (DiAngelo 2018). Consider writer Jonathan Kozol’s (1991:180) observation in 1991:

“Over 30 years ago [1961], the city of Chicago purposely constructed the high-speed Dan Ryan Expressway in such a way as to cut off the section of the city in which housing projects for black people had been built. The Robert Taylor Homes, served by Du Sable High [School], were subsequently constructed in that isolated area as well; realtors thereafter set aside adjoining neighborhoods for rental only to black people. The expressway is still there. The projects are still there. Black children still grow up in the same neighborhoods. There is nothing ‘past’ about most ‘past discrimination’ in Chicago or in any other northern city.”[3]

Today, another thirty years have passed since 1991, and many of these structures of racial exclusion remain—expressways isolating black neighborhoods, de facto segregation of neighborhoods and schools, de facto housing and job market discrimination (APAN:II:887-88; Moore 2008:5). Black race remains a key determinant (predictor variable) of life chances: one’s likelihood of well-being in various social arenas (Doane & Bonilla-Silva 2003). Whether in housing, education, wealth and income, criminal justice, or health, the gap between the de jure colorblindness of official rules and the de facto reality of their implementation continues to block genuine racial inclusion in twenty-first century America (Lewis & Diamond 2015:168).

Figure 10.1.[4] After 1968, African Americans of all socio-economic classes continued to face de facto challenges to their de jure right to live in white neighborhoods (Massey & Denton 1993:9). The absence of enforcement mechanisms in the federal Fair Housing Act (1968) meant that the burden of proving housing-market discrimination often fell on nonwhite individuals themselves (ibid:195).

In U.S. history since the Civil War, the usual and typical situation for black civil rights has been some form of de jure equality co-existing with second-class citizenship in practice. In each historical era—from Reconstruction and Gilded Age to WWII and early Cold War—most whites opposed black insistence on genuine, rather than rhetorical, equality. Although this pattern continued with 1950s-80s white resistance to racial change (Carter 2000), post-Civil Rights America also saw important advances. For instance, in contrast to previous eras, whites increasingly abandoned biological notions of black innate inferiority (Bonilla-Silva 1997). Likewise, political notions that America is a country for white people alone (white nationalism), despite periodic resurgence (Hochschild 2016), lost much of their traditional appeal. Indeed, individual prejudice (aka psychological racism) greatly weakened after the 1960s—although many whites continued to blame black culture and morality, rather than social structures created by white supremacy, for ongoing poor life chances of blacks (Feagin 2020).

However, a major continuity with apartheid has been white normativity: treating whiteness, white culture, or white experience as the norm (standard, default), and treating nonwhiteness as deviant or problematic (Brown et al. 2003; Moore 2008).[5] An analogy helps explain this concept:

Every year, your boss organizes a Christmas (rather than holiday) party at work, with Christmas trees, nativity scenes, crucifixes, biblical readings. It’s not her intention to exclude anyone, and she has no non-Christian animosity or prejudice. Nevertheless, the fact that some employees are atheist, Jewish, and Muslim results in exclusion. Perceptions that they aren’t “real” or “full” team members (don’t “fit in” or “belong”) can be consequential for their job performance and evaluation.

The analogy here is the Christian/non-Christian relationship with white/nonwhite. Though prejudiced attitudes are absent in many whites, U.S. social institutions (e.g., local governments, banks, schools and school boards, realtors, employers, police departments, hospitals) usually feature whites in higher positions of authority. Institutions have often treated white (especially middle-class) ways of acting as the standard (norm) for acceptable behavior, with black behaviors (especially working-class or poor) standing out as especially deviant (Rawls & Duck 2020). White normativity has serious consequences for nonwhites of all socio-economic levels. For example, police responses to rowdy, young black party-goers are routinely more severe than with rowdy white college students (cf. Desmond & Emirbayer 2010; Hohle 2018). Race and class work together (see Chapter 9) to escalate the severity of institutional responses to “deviant” or “antisocial” black behaviors.

Social institutions can (and often do) have racially disparate processes and outcomes, even when staffed by unprejudiced individuals of any race-ethnicity. Well-meaning people, despite their best intentions, can strongly contribute to a racially hostile, exclusionary atmosphere at work, school, place of worship, and other public places. White-normed institutions tend to produce racially disparate outcomes, with better white outcomes than nonwhite ones across many social and economic measures of well-being (Lewis & Diamond 2015:xvii-xviii). Compared to whites, and all other things being equal, after 1968 blacks continued to receive more limited and worse housing and real estate choices (Desmond 2016), worse educational outcomes (Orfield & Eaton 1996), more arrests and harsher sentences in criminal justice (Gonzalez Van Cleve 2016), fewer job callbacks (Bonilla-Silva 2018), and poorer health outcomes (Gómez & López 2013). To explain such disparities, most sociologists of race have concluded that—given declining individual prejudice—an important factor is ongoing white-normed institutional behaviors and procedures (Armenta 2017; Bonilla-Silva 2018; Duck 2015; Feagin 2020; Lewis & Diamond 2015).

10.2 Understanding White Normativity

As with a “blind spot” while driving, many whites report difficulty detecting institutional racial bias. The ways American society often privileges white (vs. nonwhite) culture and experience tend to be invisible to whites (Morrison 1992). People of color, by contrast, frequently find white-normed institutional climates highly visible.

White “blind spots” seem due especially to three factors:

(1) White-normed institutions and culture are so familiar to whites as to render them invisible. This is like “something right under your nose that you don’t see,” or “fish unaware of the water in which they swim.” By contrast, nonwhites tend to be highly aware of distinctively white American behaviors, cultures, and histories (Brown et al. 2003).

(2) As the demographic majority, most non-Hispanic whites have never had the regular experience of being the only white person in public places, on the job, at school, in one’s neighborhood, at one’s place of worship, etc. Consequently, whites often find it difficult to understand and empathize with nonwhite experiences of social isolation and racial visibility.

(3) American culture and law prioritize individual-level explanations (in terms of psychological motives and intentions) for institutional outcomes. Most Americans are less familiar with social structural, situational, and interactional explanations. In workplace, police, school, hospital, and other settings, if no individuals can be shown to display biased intent, many Americans have difficulty understanding how bias can nevertheless be operative (cf. Moore 2008:91).

The examples below—right-handedness, male normativity, and white normativity in legal education—offer further insight into white normativity. Granted, whiteness differs in some important respects from right-handedness and maleness; however, there are many similarities. Also, the observations below are descriptive and factual (not judgmental). The point here is not to judge, say, right-handers (or whites) as “bad people,” but rather to understand that many societies have systematically advantaged right-handers (and whites), and often without their even being aware of it.

Example 1: Right-handedness. Valuing right-handedness and devaluing left-handedness are social biases dating back thousands of years. Righty privilege (right supremacy) remains encoded in the English language via Latin: for instance, “dexterity” (skill, capability) literally means right-hand side, whereas “sinister” (evil intentions) means left side. Until recent decades, right-handedness was assumed to be good and normal, whereas left-handedness was bad, problematic, requiring correction.

“In Medieval times, left-handed people had more to worry about than smudging their own handwriting: Being a lefty was associated with demonic possession. While those with southpaw tendencies aren’t likely to be labeled as the devil’s puppet today, life for those in that 10 percent of the population can still be a struggle.”[6]

We wouldn’t get very far in understanding lefties if we ignored the many ways society remains designed for righties. There are no laws excluding left-handed people: and yet the design of many everyday objects—student desks, scissors, zippers, cell phones, dinner place-settings, etc.—creates daily obstacles for them. Indeed, the very meaning of left-handedness is its relationship to right-handedness, a relation of disadvantage. Right-handed normativity does not require right-handers to display any prejudicial intent toward lefties. Today, righties bear no ill will toward lefties. Rather, righties simply experience a world systematically advantaging them over lefties as familiar, ordinary, unremarkable, normal. By contrast, lefties tend to be highly aware of the daily problems created for them by righty normalization. Generation after generation, without being aware of it, righties keep remaking the “normal” world in their image, reproducing the same obstacles and problems for another generation of lefties.

Many societies are organized in terms of such binary relationships. Some social identities are deviant, whereas others—defined as opposites—are normalized. Similar observations—lefty (righty)—could be made about other relationships of disadvantage and advantage: disabled (able-bodied), female (male), poor or working class (middle class, affluent), LGBT+ (heterosexual, cisgendered), American Muslim (Christian).

Likewise with nonwhite (white). For centuries, the very meaning of “white” has been “not black or brown” (see Chapters 3-4). Example 1 shows how a color-blind society in which whites display no prejudicial intent may nevertheless continue to confer advantages to whiteness and disadvantages to nonwhiteness.

Example 2: Male normativity. A second analogy offering insight into white normativity is patriarchy (male normativity). Whereas sexism refers to individual (psychological) prejudice against women, patriarchy does not require conscious bias, just a world in which men holding most positions of authority is taken for granted as “natural” and “normal” (Freedman 2007).

Despite the victories of first-wave feminism (1800s-early 1900s: see Chapter 1), de jure sexual equality did not automatically result in de facto equality, either in the U.S. or Latin America (Lavrin 2005). Achieving the vote—the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) granting female suffrage—was a crucial victory for American female political participation and full citizenship. At a time when most men (and many women) were “male nationalists” believing only men could be full citizens, post-Women’s Rights America (1920) pointed toward full civil and political inclusion regardless of sex. Nevertheless, genuine (not merely rhetorical) gender inclusion (socially, economically, politically) remained largely unrealized until feminism’s second wave (1960s-80s), and in many ways remains unrealized today (Feinstein 2018).

Post-Women’s Rights America (after 1920) was a society which continued to largely exclude politically active women from decision-making at local, state, and national levels (APAN:II:623). By the 1950s, long after formal female equality in the political sphere, many civil rights goals remained to be accomplished for women (Friedan 2010). Women of color, in particular, experienced multiple dimensions of exclusion due to race (and often class as well). In the 1950s, female admission to medical school was usually limited to 5% of each incoming class. Similarly, in 1960 less than 4% of all lawyers and judges were women (APAN:II:766). White women did not begin to see themselves increasingly represented in high-ranking political offices until the late twentieth century. By 2020, a century after the Nineteenth Amendment, there had yet to be a female President, and women remained severely underrepresented in Congress, as state governors, and in many other high political seats. This is despite the fact that half the U.S. population is female.

Example 2 shows that American institutions have long been formally gender-blind, after much women’s-rights struggle—yet in practice often remain male normative. Just as male normativity has endured into the twenty-first century, so white normativity has continued in post-Civil Rights America. De jure color-blindness, like de jure gender-blindness, does not guarantee genuine (versus rhetorical) equality.

Example 3: White-normed legal education. Like women of any race, African Americans continue to be underrepresented in positions of authority. As noted, in the 1950s and 60s few lawyers and judges were women (APAN:II:766) despite females comprising half the U.S. population. Similarly, in 2008 “black Americans ma[d]e up less than 2 percent of important legal officials, including state attorneys general, district attorneys, leading civil and criminal lawyers, and the judges in major state and federal courts” (Moore 2008:x), despite forming 12% of the U.S. population. In the early twenty-first century, blacks continued to be severely underrepresented in positions of legal power and authority. Part of the explanation appears to be ongoing white normativity in law school education.

As sociologist Wendy Moore (2008:90) notes, discussing her ethnographic research conclusions about two elite law schools, today few white law students, faculty, or staff harbor racist intent or animosity. Nevertheless, they—like Example 1’s right-handers—may continue to reproduce the “normal” (traditional, white-normed) institution of legal education, unintentionally recreating the same racial obstacles and problems for another generation of nonwhite students and faculty (ibid:60; see also Bell 2004; Khan 2018; Wingfield 2013).

Chapter 1 introduced intersectionality: people of crosscutting social groups experience the world in contrasting ways. Elite legal education today, though formally color-blind, may continue to transmit values and assumptions characteristic of generations of wealthy white male judges, lawyers, and legal theorists. Law school trains you to “think like a lawyer”—which involves learning to see society from the perspective of these men. Adopting this perspective “comes naturally” to law students who are themselves wealthy white males (though this background doesn’t guarantee good grades). This culture tends to prioritize individualism, autonomy, instrumentalism (means-end, goal-oriented behavior), orientation to abstract rules and principles, impersonal (formal) interactional styles, emotional reserve (distance, detachment), and economic wealth (Domhoff 2017).

Law students who don’t share much of this elite white male culture may face unstated, informal obstacles not experienced by students who do. Professional education requires secondary socialization: internalization of the profession’s values and culture (e.g., law, medicine, business, science: Abbott 2014). According to Moore (2008), some law students of color report extreme personality transformations in their struggle to adopt white male values and “think like a lawyer.” This culture clash factors into attrition rates of students of color. By contrast, white male students, like “fish in water,” though not necessarily good students, tend to find legal education’s values normal and natural. Thus, the seemingly racially neutral “lawyer” identity, in the experience of many law students of color really means thinking like a white man.

Example 3 indicates how institutional normalization of whiteness in legal education works. Society depends on people having babies to reproduce a population; similarly, institutions (e.g., law, education, medicine, government, religion) from generation to generation must be reproduced. Elite law schools today, to the extent that they uncritically reproduce traditional elite white male values and assumptions, pose unstated challenges to students and employees not sharing this culture (Bell 2004).

10.3 De Facto Residential Segregation

As we’ve seen, in much sociological explanation of enduring black-white disparities, white normativity plays a key role. White-normed social institutions, in turn, have contributed to the maintenance of exclusionary social structures with roots in pre-1970 white supremacy. One of the most consequential of these structures for limiting African American opportunity has been the black ghetto (see Chapter 9).

Writing in the 1990s, demographers Massey and Denton (1993) noted that most Americans vaguely recognized that U.S. cities after 1968 remained racially segregated in practice, with identifiable black neighborhoods (Massey & Denton 1993:1). Though federal law barred housing discrimination (Fair Housing Act of 1968), de facto segregation has remained a powerful obstacle to social, economic, and political opportunities for African Americans (Bell 2004; Klinkner & Smith 1999:323; Moore 2008:24-25; Telles & Ortiz 2008:160). In Brazil, segregation of black/brown homes from white homes has been “only” moderate, similar to U.S. segregation of Asian American homes from white homes. However, as compared to Brazilian cities, black-white residential dissimilarity[7] in many U.S. cities is far higher. At the turn of the twenty-first century, dissimilarity ranged from 92 in Chicago (almost complete segregation) to 75 in New York City (Telles 2004:202).

Social isolation of blacks via discriminatory housing markets has long been the cornerstone of American apartheid (Desmond 2016; see Chapter 8). The first half of the twentieth century was a time of black mass migration (aka the Great Migration) from the rural South to cities, particularly in the North but also in the South and West. By the end of the 1960s, about 80% of blacks lived in cities rather than rural areas (Massey & Denton 1993:18). Thus, post-1968 housing patterns in cities pertained to the vast majority of African Americans.

Residential segregation has never simply been the “choice” of blacks to live with other blacks. During the Great Migration, northern WASPs and white ethnics fiercely rejected the newcomers, forcing African Americans—mostly poor and working class, but also middle class—together into mono-ethnic ghettos (see Chapter 6). These were zones of dilapidated, overpriced, and overcrowded housing with poor to nonexistent municipal services. With more and more black migrants arriving from the South, especially after the First World War (1918), the result was large black neighborhoods abutting white ones in many northern cities: e.g., New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis (Drake & Cayton 1970). With 1940s-60s suburbanization, whites abandoned these cities’ “inner” zones, which expressway construction isolated still further (Klinkner & Smith 1999). Thus was born the “inner city,” an urban zone of racialized poverty and few jobs.

In this way, white exclusion (1877-1968) created the twentieth-century black ghetto, the most extreme form of racial-ethnic residential segregation ever to exist in North America. Whereas 1800s-early 1900s WASP exclusion created white-ethnic immigrant neighborhoods (e.g., Irish, Jews, Poles, Hungarians, Italians), these were not mono-ethnic (see Chapter 6). So-called “Italian” or “Jewish” neighborhoods almost never contained over 50% of that ethnic group. For white ethnics, the highest level of spatial isolation ever recorded in the United States was 56%, for Italians in 1910 Milwaukee. In contrast, by 1970 the lowest level of black spatial isolation anywhere in the nation was 56% in San Francisco (Massey & Denton 1993:49). White racism ensured that Asians, Mexicans, and especially African Americans mostly lived in mono-ethnic neighborhoods (APAN:II:495; see Chapter 6). Mono-ethnicity of Chinatowns, Mexican barrios, and black ghettos socially isolated these groups and limited their upward mobility (Ortiz 1996). By contrast, white ethnics had more opportunities to escape urban slums, moving to working-class and middle-class WASP neighborhoods in the city, suburbs, and rural areas (Massey & Denton 1993:9).

Accordingly, a major goal of the 1954-1968 Civil Rights movement was open housing—federal rules against racial discrimination in housing markets. Although by 1968 black activism had succeeded in pressuring Congress to pass the Fair Housing Act, the bill’s opponents ensured that its enforcement measures were removed (Massey & Denton 1993:195; see Chapter 8). Thus, an old pattern—civil rights laws lacking enforcement measures—was repeated, resulting in continuing residential segregation (de facto rather than de jure) during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries (Desmond & Emirbayer 2010; Duck 2015). Black-white residential segregation illustrates the ongoing gap between genuine and merely rhetorical equality in post-Civil Rights America.

10.4 De Facto Educational Segregation

Like white normativity and residential segregation, educational segregation remained a major obstacle to African American inclusion in the early twenty-first century.

As during formal apartheid (in the South) and informal apartheid (in the North and West), so today America remains a society of racially separate and unequal education (Brown et al. 2003; Desmond & Emirbayer 2010; Orfield & Eaton 1996). For example, in 1991 Washington, D.C.’s schools were 92% black, and Detroit’s school system was 89% black (Kozol 1991:185, 198). In 1992 (38 years after Brown v. Board in 1954), more than 33% of black students were still in schools of over 90% minority students. In the same year, almost 50% of white students nationwide were in schools of at least 90% white students. In the Midwest and Northeast, over 66% of white students attended virtually all-white schools (Klinkner & Smith 1999:323). “[S]chools in the United States today [2008] are as racially segregated as they were at the time of the Brown decision [1954], more in some areas” (Moore 2008:64). As during apartheid, today’s black-white disparities in school quality and funding are exacerbated by housing segregation. This is because public school district funding is based on local real estate values and property taxes. Poor communities in the U.S. usually don’t have access to well-funded education, and blacks are much more likely to be poor than are whites.[8]

As with housing, the 1954-1968 Civil Rights movement prioritized school desegregation (Fredrickson 1981:274; Morris 1986). White resistance to desegregation began immediately after the Supreme Court’s Brown decision (1954), with local and state governments in the South initially relying on the traditional anti-Civil Rights strategy of shutting down a public service (here, public education) rather than integrating it (Hohle 2018). When desegregation pressures came to the North, white resistance there was likewise fierce. White flight to suburbs and anti-busing politics during the 1960s-70s further increased black social isolation in inner cities.

For example, in Boston white flight (combined with foreign immigration) transformed the racial composition of the school system between 1970 and 2012. The most dramatic drop in white students occurred during the 1970s, when Boston schools became majority-minority:

Table 10.1. White percentage of children in Boston public schools

| Year | White percent of students |

| 1970 | 64% |

| 1980 | 35.5% |

| 1990 | 22.2% |

| 2000 | 14.7% |

| 2012 | 13% |

Source: Hohle 2018:179 (from U.S. Census, Boston Public Schools, 2012)

Among the 1970s-80s Supreme Court cases supporting white backlash against civil rights advances was Milliken v. Bradley (1974; see Chapter 8). The Court, though continuing to oppose de jure school segregation, effectively upheld de facto educational segregation (Kozol 1991:200-201). In sum, both factors—southern and northern white backlash against the Civil Rights Movement, and racially retrogressive Supreme Court decisions—allowed school segregation to continue in the post-Civil Rights era (Desmond & Emirbayer 2010; Orfield 1993).

Continuities of school segregation from apartheid to the post-Civil Rights era help to explain the racial achievement gap of recent decades. This term refers to academic achievement disparities—high school and college completion rates, grade point averages, test scores—between black and/or Latinx students, and white students (Lewis & Diamond 2015:2; cf. Steele 2011). The gap was not new after 1970; rather, its continuing existence pointed to ongoing educational inequality. On the one hand, schools continued to vary in quality and funding by race (e.g., white suburbs vs. black city). On the other hand, within the same school, accumulated white family resources and networks continued to be much superior on average to those of black families (Kozol 1991:119; Lewis & Diamond 2015:10). Moreover, white normalization in schools continued to contribute to racially disparate outcomes. The cumulative effect of many decisions (usually color-blind and well-intentioned) by parents, teachers, and counselors was that, within the same school, white students ended up being disproportionately tracked into the best classrooms, and blacks into the worst (Desmond & Emirbayer 2010). Generations of students after 1970, just as during apartheid, learned in school to associate blacks with poor academic performance, and whites with overall better performance (Lewis & Diamond 2015:11-12).

Likewise, studies of school discipline have revealed patterns of racial profiling similar to those found in policing and criminal justice (Alexander 2010). Racialized discipline may unfairly focus on black and brown students, or it may treat white youth as intrinsically innocent (Lewis & Diamond 2015:48-49). According to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights, black students and especially black males are much more likely than white students to receive suspensions or be expelled from school (ibid:47). Accordingly, white normalization in schools contributes to the schools-to-prison pipeline, an all-too-common trajectory of young, black males in post-Civil Rights America (Alexander 2010; Kozol 1991:118).

In sum, public education plays a crucial role in American equality of opportunity; yet African Americans across a range of socio-economic classes are disproportionately concentrated in segregated, poorly funded schools of low quality (Hohle 2018:186; Orfield 1993; Orfield & Eaton 1996). Contemporary educational segregation represents a major continuity with pre-1970 American apartheid, and an important reminder of the limits of the victories of the Civil Rights Movement (Kozol 1991:2-3). Parallels in education between the post-Reconstruction era (1877) and post-Civil Rights era (1968) further support the claim that our era is one of overall white retreat from commitment to genuine racial equality (Klinkner & Smith 1999; see Chapter 9).

Chapter 10 Summary

Chapter 10—discussing white normativity and de facto segregation—continued Chapter 9’s explanation of why most sociologists see racial inequality as largely ongoing, rather than overcome, in the post-civil rights era. Section 10.1 distinguished individual prejudice from white normativity. Although white Americans after 1970 increasingly disavowed racist attitudes, institutional normalization of whiteness continued to block genuine nonwhite inclusion.

Section 10.2 provided three illustrations of white normativity, using the examples of right-handedness, male normativity, and law school education. The examples show how—despite the best intentions of many whites lacking discriminatory intent—systemic racism may continue to thrive in today’s institutional environments (e.g., law schools).

Section 10.3 introduced de facto residential segregation as an ongoing obstacle to genuine African American inclusion. Socially isolated housing continued to powerfully constrain black social, economic, and political opportunities, long after de jure open housing in 1968.

Section 10.4 introduced de facto educational segregation. Like residential segregation, poorly funded and segregated schooling has endured in the post-civil rights era, severely limiting black opportunities.

[1] Left image: Public domain. Right image credit: Creative Commons license (“New Classroom at BES” by BES Photos is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

[2] Wallace’s gubernatorial terms were 1963-67, 1971-79, 1983-87. See Wikipedia: “George Wallace.” Accessed 6/23/21.

[3] CREDIT LINE: Excerpt(s) from SAVAGE INEQUALITIES: CHILDREN IN AMERICA’S SCHOOLS by Jonathan Kozol, copyright © 1991 by Jonathan Kozol. Used by permission of Crown Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

[4] Image credit: Creative Commons license (“House for sale” by Mundoo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[5] Aka systemic racism, structural racism, institutional discrimination, racism without racists.

[6] Source: “11 Everyday Tasks That Are Tricky for Left Handers” by Jake Rossen. Mental Floss (August 1, 2019). Accessed 6/27/21.

[7] The dissimilarity index (D) is a demographic measure of segregation. It measures the percentage of a social group that would have to move to a different census tract to achieve the same residential distribution as another social group. D varies from 0—same distribution—to 100—total segregation (Telles 2004:201-202).

[8] According to the 2010 U.S. Census, “25.7% of African Americans and 25.4% of Hispanic Americans [were] living below the federal poverty line, compared to less than 10% of white Americans.” Source: Equal Justice Initiative 2019 Calendar: “A History of Racial Injustice.” https://eji.org/