UNIT IV: IMMIGRATION AND LATIN AMERICA

The images above[1] illustrate legacies of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American imperialism. Hurricane María (left image) made landfall in Puerto Rico in September 2017, when Carmen Yulín Cruz (right image) was mayor of San Juan, the capital of this U.S. territory.

The Category 5 storm devastated the U.S. Caribbean territory of Puerto Rico, home to more American citizens than 21 of the 50 states. More Americans live in Puerto Rico than in, for example, Utah, Iowa, Nevada, Arkansas, Mississippi, Kansas, New Mexico, Nebraska, West Virginia, New Hampshire, or Rhode Island.[2] Similarly, the combined population of U.S. territories (3.6 million: Puerto Rico, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa) is greater than that of the non-contiguous states (2.1 million: Hawai’i, Alaska).[3] Following the disaster, Puerto Rico received little aid from the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA). Not coincidentally, the island has little political clout in Washington. A U.S. possession since 1898, islanders—Hispanic Spanish-speakers—have no voting representatives or senators in Congress and no Electoral College votes. They cannot vote in presidential or any other federal elections. In many ways, Puerto Rico today remains a U.S. colony: highly taxed, little political representation, and invisible to most mainland Americans. Puerto Rico illustrates how social groups with relative power (e.g., residents of U.S. states) often have little awareness of the experiences of marginalized groups lacking power (e.g., U.S. territories).

What is the relationship between the mainland and overseas U.S.? How do American citizens of the territories view the mainland? How did American ideologies of exceptionalism and manifest destiny—often connected to white nationalism—influence direct and indirect rule in the Caribbean and Pacific?

Chapter 12 Learning Objectives

12.1 Statehood and White Nationalism

- Define imperialism

- Distinguish between U.S. states and territories

- Understand the historical link between statehood and white nationalism

12.2 American Exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny

- Define American exceptionalism

- Define manifest destiny

12.3 Growth of American Republican Empire, 1846-1914

- Define the Spanish-American War

- List three examples of U.S. imperialism in the period 1865-1914

- Define white grievance

12.4 Empire of Liberty, 1898-1945[4]

- List three examples of U.S. intervention in Latin America, 1898-1945

- Distinguish between military and economic imperialism

Chapter 12 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

imperialism: the political policy or doctrine, pertaining to an empire, of asserting or enforcing control over a foreign entity. Although the U.S. has never officially been an empire, its geographical expansion resembled in important respects European imperial expansion and colonialism, especially during the second wave of European empire-building in the late 1800s and early 1900s. (See below for military vs. economic imperialism.)

territory: U.S. administrative region in which residents possess federal citizenship but lack state citizenship

state: U.S. administrative region in which residents possess both state and federal citizenship

American exceptionalism: an ideology stating that the U.S., unlike most other nations, has usually been a force for good in the world

manifest destiny: an ideology stating that U.S. geographic expansion is preordained (e.g., in God’s providential plan). Especially prior to 1945, this view was explicitly white supremacist and anti-Catholic.

Spanish-American War: Conflict in which the United States defeated the declining Spanish Empire, mostly in Cuba (1898). The Treaty of Paris (1899) granted the U.S. the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and indirect rule over Cuba. The war marked the arrival of the U.S. as a twentieth-century world power.

Open Door policy: after 1900, a U.S. foreign policy ideology rationalizing foreign intervention as necessary to America’s survival. (See economic imperialism.)

white grievance: a racial group resentment reflected in politics, in which whites see themselves (rather than nonwhites) as the true victims in race relations. E.g., European and American imperialism’s “white man’s burden” (Kipling 1899) of governing nonwhite populations.

military imperialism: imperial domination in the form of military conquest or rule

economic imperialism: imperial domination in the form of mercantilist or modern capitalist economic penetration. E.g., Open Door policy.

12.1 Statehood and White Nationalism

From the Founders’ generation onward (1770s), the U.S. has never wanted to describe itself as a colonial power (Dunbar-Ortiz 2014). Rather, Americans long saw themselves as exceptional among nations, a people specially endowed with democratic virtue (see Chapter 2). They associated colonialism with old European monarchies and empires, and their own continental absorption of Native American territories and resources as fundamentally different from Old World imperialism.

Using rhetorical contrasts (civilized vs. savage, white vs. Indian, Christian vs. heathen), European Americans rejected the legitimacy of indigenous polities like Iroquois, Seminole, Cherokee, Miami, or Sioux (Drinnon 1997; Ostler 2004). They saw foreign relations between European states (e.g., Britain and France) as different in kind from U.S. relations with Indian nations. Thus, the U.S.-Native relationship, beginning in colonial times, was always marked by a strong contrast between theory and practice, words and actions. Theoretically, the U.S. Constitution acknowledged the national sovereignty of each of the many Native peoples. For example, agreements between the U.S. and Native nations were signed and ratified just like international treaties with European nations. However, the actual conduct of U.S. treaty making and breaking with Indian peoples was characterized by bad faith: fraud, dishonesty, hypocrisy (APAN:I:252). The result of the long trail of broken treaties was U.S. continental expansion “from sea to shining sea.” American reluctance to straightforwardly describe this process as imperialism or colonialism stemmed from the gap in U.S.-Native relations between theory (legally binding treaties) and practice (fraudulent treaty violations). Likewise, much the same can be said about U.S. direct and indirect rule in Latin America and the Pacific, processes originating in the 1846-1848 Mexican War (Weber 1982).

Imperialism refers to the political policy or doctrine, pertaining to an empire, of asserting or enforcing control over a foreign entity. The U.S. has always been a geographically growing republic, never officially an empire. But its westward expansion resembled in many ways European imperial growth and colonialism, especially during the second wave of European empire-building of the late 1800s and early 1900s (see Chapter 4). Likewise, much insight can be gained into America’s growing “empire of liberty” (APAN:I:210, 216-17; Wood 2009)—Thomas Jefferson’s phrase—through comparison and contrast with other Western Hemisphere polities like Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina.[5]

Consider President Jefferson’s (1800-1808) precedent-setting argument on the constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase. His administration, acting unilaterally and independently of Congress, doubled the size of the U.S. by purchasing the Louisiana region west of the Mississippi River (including New Orleans) for $15 million from France (APAN:I:216).

“The constitution has made no provision for our holding foreign territory, still less for incorporating foreign nations into our Union. The Executive in seizing the fugitive [fleeting] occurrence which so much advances the good of their country, have done an act beyond the Constitution.”[6]

At the stroke of Jefferson’s pen, hundreds of thousands of people in the Louisiana territory became subjects of the American republic overnight (APAN:I:216-17). From Spanish imperial subjects to French republican subjects, now they became U.S. republican subjects. This politically ambiguous status did not automatically lead to U.S. citizenship rights. Although the Louisiana Purchase treaty specified that “the inhabitants of the ceded territory” would be accorded such rights, free people of color (for instance) found themselves excluded from the right to vote in American elections and serve on American juries (ibid).

Crucial to understanding U.S. imperialism is the distinction between U.S. territories and states. A state (e.g., Rhode Island, Arkansas, Oregon, Hawai’i) is a U.S. administrative region with strong local identity in which residents possess both state and federal citizenship (see Chapter 8). American history since 1776 has featured much ambiguity and conflict over the relation of federal to state authority. By contrast, a territory (e.g., Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa) is a U.S. administrative region in which residents possess federal citizenship but not state citizenship. The territory system began in the late 1700s as a preliminary stage to statehood. However, national expansion in North America, the Caribbean, and Pacific encountered many non-WASP, nonwhite populations. When such populations were large, as in New Mexico (1846), Puerto Rico (1898), the Philippines (1898), or Hawai’i (1898), many whites opposed these possessions or annexed territories becoming states. To them, full membership in the nation seemed to require white racial identity. As we’ve seen (Chapters 5-7), this political view is called white nationalism: the belief that only whites—especially English-speaking, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant men—should be full members of the United States.

For example, New Mexico statehood was delayed for decades (1846-1912: 66 years) by white nationalist sentiment in Congress (Gómez 2018:118-19; see Chapter 6). Not until New Mexico Territory added a sizeable white, Protestant, English-speaking population—politically and economically dominant over the existing Spanish-speaking Mexican Catholic and Indian populations—did it become a state (Weber 1982). Similarly, Puerto Rico has remained a territory since 1898 (over 120 years) largely due to its deeply rooted non-WASP institutions, as well as disagreements among Puerto Ricans themselves (Briggs 2002; Findlay 1999).

Likewise, the slavery extension controversy (1820-1860)—over territories entering the Union as slave or free states—illustrates how white nationalism (e.g., free-labor ideology: see Chapter 5) often played a key role in the statehood process. For instance, consider the political issues leading to Oregon’s statehood in 1859:

“In December 1844, Oregon [Territory] passed its Black Exclusion Law, which prohibited African Americans from entering the territory while simultaneously prohibiting slavery. Slave owners who brought their slaves with them were given three years before they were forced to free them. Any African Americans in the region after the law was passed were forced to leave, and those who did not comply were arrested and beaten. They received no less than twenty and no more than thirty-nine stripes across their bare back if they still did not leave. This process could be repeated every six months. Slavery played a major part in Oregon’s history and even influenced its path to statehood. The territory’s request for statehood was delayed several times, as members of Congress argued among themselves whether the territory should be admitted as a “free” or “slave” state. Eventually politicians from the south agreed to allow Oregon to enter as a “free” state, in exchange for opening slavery to the southwest United States.”[7]

Thus, race played a key role in U.S. acquisition and governance of territories, and in admittance of new states. Generally, territories achieved statehood only after adding a white (WASP) population sufficiently powerful to counter the political influence of resident nonwhites (cf. Dunbar-Ortiz 2014; Gómez 2018). This pattern reflects the pervasive influence of white nationalism in American history.

12.2 American Exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny

Likewise crucial to understanding U.S. imperialism are (1) exceptionalism and (2) manifest destiny.

(1) American exceptionalism is a nationalist ideology stating that the U.S., unlike most other nations, has usually been a force for good in the world (Madsen 1998; see Chapter 2). Much like the nineteenth-century British Empire, America has long seen itself as having a unique, God-given role or providential mission in international relations and foreign policy. In this view, U.S. power is largely benevolent and altruistic, contrasting with European imperialism and colonialism by morally and politically improving dominated peoples as their steward. As during the Cold War, so in the early twenty-first century American occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq, U.S. foreign policy has frequently sounded this theme.

The roots of exceptionalism date to the very beginning of English colonization in North America. John Winthrop’s (c. 1630) description of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Boston as “a city on a hill”[8] was an early version. Another example is Thomas Paine’s political pamphlet Common Sense (1776): “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” And Washington’s Farewell Address (1796), mostly written by Alexander Hamilton and delivered at the end of Washington’s second presidential term, sharply distinguished between Europe and the U.S., emphasizing the latter’s uniqueness and exceptionalism (APAN:I:195).

(2) Manifest destiny, in turn, was tightly bound to exceptionalism. This ideology likewise shows deep links between white supremacy and American identity in the nineteenth century (Horsman 1981). As we’ve seen (Chapter 6), it was a collection of ideas claiming God’s intention that U.S. whites expand across the North American continent. For example, Americans justified the war with Mexico (1846-1848) in these terms: as the destiny of a racially superior and chosen people to spread across regions currently inhabited by Indians and Mexicans (APAN:I:331; Blight 2008, Lecture 4, 36:09). In subsequent decades, Americans would continue to justify their territorial expansion and rule (republican imperialism) in Latin America and the Pacific in this way. They saw themselves as having a God-given right or duty to bring American and Protestant Christian institutions to less fortunate and “inferior” peoples incapable of governing themselves (APAN:I:355).

Walt Whitman (1819-1892), one of America’s most influential poets, memorably voiced manifest destiny’s expansive sense of American mission, nationalism, and idealism. For example, “For You O Democracy” (1855) begins: “Come, I will make the continent indissoluble, / I will make the most splendid race the sun ever shone upon, / I will make divine magnetic lands…” (Whitman 1965:117).

12.3 Growth of American Republican Empire, 1846-1914

Two of U.S. imperialism’s most fateful inflection points were the Mexican Cession (1846-1853) and the Spanish-American War (1898). War with Mexico created the modern Mexico-U.S. border and American Southwest, consolidating the nation’s continental expansion to the Pacific Coast (Gómez 2018; see Chapter 6). War with Spain delivered Caribbean and Pacific possessions, certifying the nation’s “arrival” as a global power and peer of Europe, and setting the stage for twentieth-century American globalism (Fuente 2001).

Sectional (North-South) polarization in the 1850s scuttled early attempts at Pacific and Caribbean expansion. Proposals to annex Hawai’i as a territory, which eventually succeeded in 1899, started under the Pierce Administration (1852-1856) but could not overcome southern senators’ opposition to an additional free state (APAN:I:364-65). Likewise under President Pierce, northerners opposed proposals[9] to purchase or conquer slaveholding Cuba, one of Spain’s Caribbean colonies (ibid:365). Following the 1860 Democratic Party split, the Northern Democrats pledged to support the fugitive slave law, honor the Dred Scott decision, and pursue “the acquisition of the Island of Cuba” (quoted in Levine 2005:216).

With white reunification after the Civil War and Reconstruction, many Americans returned to an expansive mood. A key visionary of American globalism was Secretary of State William H. Seward, who in 1867 orchestrated purchase of Alaska from Russia and possession of the (Pacific) Midway Islands. Throughout his terms as New York senator (1849-1861) and U.S. secretary of state (1861-1869), Seward forcefully pushed expansionism, comparing the growing United States to the expansionist ancient Roman Republic and Roman Empire: “There is not in the history of the Roman Empire an ambition for aggrandizement so marked as that which characterizes the American people” (quoted in APAN:II:572). He envisioned a large American empire incorporating the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America, the Pacific, Canada, Greenland, and Iceland (ibid).

By the late 1800s, the U.S. was rapidly emerging as one of the world’s largest industrializing economies. In accordance with its economic stature, the nation sought an international commercial, political, and military role as a “great power” peer of European states like Britain and France. Thus, the U.S. embraced the Spanish-American War (1898) as an opportunity to acquire imperial power status in a geopolitical environment of competitive European world empires “scrambling” for new colonies (Klinkner & Smith 1999:99). By 1900, with Spain’s global empire crumbling and waning British influence in the Western Hemisphere, the U.S. had arrived: a newly global power with dominance in Latin America and possession in the Pacific of Hawai’i, the Philippines, American Samoa, and Alaska (APAN:II:566).

Open Door policy is particularly important for understanding U.S. twentieth-century interventionism in Latin America (see section 12.4 below and Chapter 13). This foreign policy strategy took shape in response to the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) in China, which threatened to shut China to foreign trade. U.S. Secretary of State John Hay proposed an “open door” approach, which subsequently became a touchstone for twentieth-century American foreign policy and diplomacy. The ideology had three main principles: (1) exports to foreign markets were necessary for U.S. domestic economic health; (2) economic and military intervention abroad was necessary for keeping foreign markets profitable to American business; and (3) any restriction of access abroad to American commodities, ideas, or citizens should be regarded as endangering America’s very survival (APAN:II:580). Keeping the Open Door was the key ideological rationale for America’s many twentieth-century economic and military interventions in the internal affairs of sovereign nations, especially in Latin America.

Table 12.1. U.S. Imperialism Timeline, 1865-1914[10]

| Date(s)

|

Event(s) |

| 1861-69

|

Secretary of State William H. Seward promotes U.S. expansionism |

| 1867

|

Possession of Alaska and Midway |

| 1876-1910

|

Porfirio Díaz’s thirty-four-year dictatorship in Mexico is supported by U.S. business interests |

| 1878 | United States acquires naval rights in Samoa

|

| 1885 | Reverend Josiah Strong’s Our Country promotes manifest destiny

|

| 1887 | United States acquires naval rights at Pearl Harbor (Hawai’i)

McKinley Tariff harms Hawaiian sugar exports

|

| 1893 | U.S. economic recession causes business failures and mass unemployment

Pro-U.S. interests depose Queen Lili’uokalani of Hawai’i

|

| 1895 | Cuban revolution against Spain nears its end

Japan wins war against China, and possesses Korea and Formosa (Taiwan)

|

| 1898 | U.S. formally acquires Hawai’i

U.S. battleship Maine explodes in Havana harbor Spanish-American War

|

| 1899 | Treaty of Paris negotiated, resulting in enlarged U.S. empire

U.S. multinational United Fruit Company acquires land and dominates markets in Central America Philippine rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo challenge U.S. rule

|

| 1901 | President McKinley assassinated; Theodore Roosevelt becomes president

|

| 1903 | U.S. gains canal rights in Panama

Platt Amendment establishes U.S. indirect rule over Cuba

|

| 1904 | Roosevelt Corollary asserts American “police power” in the Western Hemisphere

|

| 1905 | Russia-Japan War ends with Portsmouth Conference, in which President Roosevelt plays a key role

|

| 1906 | Asian American schoolchildren segregated by San Francisco School Board

U.S. invasion of Cuba

|

| 1907 | U.S. Navy (the “Great White Fleet”) tours the world, demonstrating American military power

|

| 1910 | Mexican Revolution begins, threatening U.S. business interests

|

| 1914 | U.S. invades Mexico at Veracruz

Start of First World War Opening of Panama Canal

|

America’s style of imperialism and colonialism resembled, yet also differed from, that of Europe. It shared Europe’s white supremacist ideology of the second wave of empires of the late 1800s and early 1900s (e.g., in Africa, India, Southeast Asia: see Table 4.3). This was an age of intensifying racism, allied with imperialism and eugenics, that saw “civilization” and “whiteness” as largely identical (APAN:II:569; Ferrer 1999; Kevles 1995; see Chapter 4). For example, British colonial poet Rudyard Kipling (1899) celebrated U.S. acquisition of the Philippines in the same way he praised British rule in India: as the “burdensome” duty of white men tasked with a global mission to govern nonwhites (APAN:II:581). Both European and American imperialists had long argued that the social problems of nonwhites were caused by their own moral failings, not white rule. According to President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), alleged black “laziness and shiftlessness” and “vice and criminality of every kind” caused more “harm to the black race than all acts of oppression of white men put together” (quoted in Klinkner & Smith 1999:105). Thus, white grievance against nonwhites was a resentment shared by white Americans and Europeans (cf. Gest [2016] on white grievance today). It blamed the victims of racist imperialism for all problems, soothing white consciences.

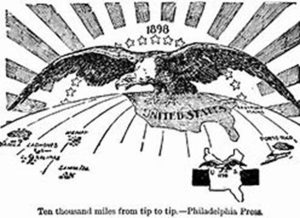

Figure 12.1. U.S. Imperialism.[11] This political cartoon, contemporary with the Spanish-American War (1898), shows a westward-facing American eagle spreading its wings, “Ten thousand miles from tip to tip.” The sun of American power is rising over various Caribbean and Pacific islands such as “Porto Rico.”

However, as compared to Europe, U.S. imperialism was also distinctive. Unlike officials of the British or German Empires, Americans were less forthright about naming their overseas activities as “colonial” or “imperial.” Like France after 1870, the U.S. did not officially describe itself as an empire (Horne 2003). Yet the French Third Republic (1870-1940) was a global colonial power with possessions in the Caribbean and South America (e.g., Martinique, French Guiana), Africa (e.g., Algeria), the Indian Ocean (e.g., Madagascar), Southeast Asia (e.g., Vietnam), and the Pacific (e.g., Tahiti). Likewise, by the early 1900s, the U.S. was a republic with far-flung overseas possessions, a colonial power whose foreign policy was couched in the language of “democracy” and “liberty” (Fuente 2001; Turits 2003).

12.4 Empire of Liberty, 1898-1945

As in the nineteenth century, Americans after 1898 questioned the fitness for democratic self-rule of non-WASP and nonwhite populations (Ferrer 1999; Scott 2000). In its new possessions (Philippines, Puerto Rico), territories (Hawai’i), and satellite states (Cuba, Dominican Republic), the U.S. was able to act on these doubts. Two important steps toward post-1945 American globalism (Chapter 13) were (1) U.S. governance of nonwhite Caribbean and Pacific islanders allegedly incapable of conducting their own affairs, and (2) frequent interventions in sovereign Latin American nations.

(1) Direct or indirect American rule. In U.S. imperialist eyes, Caribbean and Pacific peoples would benefit from a tutorial in American democracy of unspecified duration: direct or indirect U.S. rule. If they proved racially capable of “maturing” into political “adulthood,” then America—like a guardian or tutor—would either grant them independence or graduate them to full membership (statehood) in the Union. Congress would decide their democratic fitness; they themselves had little say in their own political destinies.

Unsurprisingly, these peoples did not always see themselves as wards needing an American guardian. They tended to oppose Yankee tutelage, though politically and militarily unable to eject the Americans. This was especially the case with Cuba and the Philippines, which by 1898 had already fought protracted wars of independence from Spain, experiences that had generated much nationalistic fervor (Ferrer 1999). Following American entrance into these conflicts and defeat of the Spanish, U.S. propaganda shifted from support of independence to American tutelage (Fuente 2001). By the early 1900s, many Cubans and Filipinos had become disillusioned with the Americans, seeing them as merely a new colonial master, albeit one seeking to improve local sanitary, medical, and educational conditions (APAN:II:575-76). During the U.S.-Philippine War (1899-1902), in which over 4,000 Americans died, about 20,000 Filipinos were killed in combat, and approximately 600,000 died from war-related disease and starvation (APAN:II:579). Following U.S. suppression of the rebellion, Americans maintained their rule over the Philippines until the aftermath of WWII (1898-1946). In the U.S. experience in the Philippines, there is much that foreshadows later, Cold-War events. For example, the Vietnam War: after driving out the French (1954), the northern Vietnamese soon found themselves fighting to expel the United States (1955-1975).

Also, domestic American apartheid overlaps in important ways with overseas imperialism (1898-1945). As with nonwhites overseas, white Americans had long questioned the fitness for democratic citizenship of nonwhites at home, especially African Americans. We’ve seen that the rise of American apartheid after 1900 (Chapter 8) was part of global worsening racism in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The height of U.S. imperialism in Latin America and the Pacific (1898-1945) significantly overlapped with domestic apartheid (1877-1968). Accordingly, the white supremacy of the new U.S. authorities interacted in complex ways with existing local practices of Spanish colonial white supremacy. Cuba and Puerto Rico, for instance, like the American South, had for centuries been Spanish plantation societies based on black slavery. Indeed, emancipation in Cuba came later (1886) than in the U.S. (1863) (see Ferrer 1999; Scott 2000). Just as the U.S. claimed to exercise guardianship or trusteeship over politically “immature” nonwhites overseas, so white segregationists at home claimed to be acting in the best interests of black Americans (Fredrickson 1981:190).

Thus, the future society that American officials (early 1900s) envisioned for Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawai’i and the Philippines resembled in many ways the Jim Crow South—racial separation, political disfranchisement, and economic exclusion of black and brown people. U.S. imperialism overseas often involved an imported apartheid component, based on white American notions of “appropriate” social and legal relations between nonwhites and whites.

(2) U.S. interventionism in Latin America. Like American imperial governance, military and economic interventionism (1898-1945) was a crucial step toward American globalism. Open Door policy justified aggressive U.S. tactics for influencing policy in sovereign or semi-sovereign Latin American nations in ways that reflected exceptionalism and manifest destiny.

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), in particular, advocated an interventionist foreign policy. In the Roosevelt Corollary (1904) he described interventionism in neutral terms as America’s “police power” to police the globe (APAN:II:678). States such as Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, etc. were, in Roosevelt’s eyes, racially inferior and “destined” to be dominated by white Americans (ibid:581). Roosevelt and later U.S. presidents used the Roosevelt Corollary to justify foreign intervention. For example, between 1900 and 1917, presidents sent U.S. troops to Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Mexico (ibid:583). The soldiers put down resistance to U.S. influence, seized bases and ports, intervened in civil wars, and prevented European intervention. American officials controlled elections, trained and armed militias that later seized power, and extended U.S. financial control over local economies. After WWI (1918), American desire for new colonial possessions in the Caribbean continued. For instance, in 1929 Britain declined President Hoover’s offer to erase Britain’s entire WWI debt to the U.S., in exchange for U.S. acquisition of British Honduras (Belize), Trinidad, and Bermuda (ibid:644).

Table 12.2 below shows that interventions embodying U.S. imperialism took two forms: military and economic. Often the two approaches worked in tandem, with military force extending and protecting U.S. commercial interests; but in some cases they were separable (APAN:II:578, 663). Open Door policy rationalized the interventions as necessary to protect American economic, security, and ideological interests. U.S. military imperialism involved sending troops and influencing national policy (e.g., in Cuba or Nicaragua) through force or the threat of force. Economic imperialism took the form of capitalist economic penetration benefiting U.S. interests and local elites, but tending to extract and deplete national resources (soil and subsoil) for foreign consumption (e.g., sugar, tobacco, petroleum, minerals, fruit) in ways that acted against the long-term interests of most local people (Velázquez 2010; cf. Alonso 2014). U.S. economic control of Central American and Caribbean “banana republics” (originally referring to Honduras) significantly contributed to post-1945 political unrest in these regions (Holt 1992; McCook 2002; see Chapter 13).

Table 12.2. U.S. Military and Economic Interventionism in Latin America, 1918-1939[12]

| Region

|

Interest or event |

| Chile | U.S. copper extraction |

| Argentina (Buenos Aires) | Pan-American Conference, 1936: U.S. agrees to nonintervention pledge |

| Venezuela | U.S. oil interests |

| Panama | U.S. possession of Canal Zone |

| Declaration of Panama, 1939 | |

| Nicaragua | U.S. financial supervision, 1911-24 |

| U.S. military occupation, 1912-25 | |

| U.S. war against Sandino,[13] 1926-33 | |

| Somoza era, 1936-79 | |

| Honduras | U.S. troops, 1924 |

| United Fruit Company is large landowner | |

| Mexico | 1917 Constitution challenges U.S. interests |

| Nationalization of foreign oil companies, 1938 | |

| U.S.-Mexico agreement settles oil dispute, 1942 | |

| Cuba | U.S. troops, 1917-22 |

| U.S. investors control sugar industry | |

| Revolution of 1933 | |

| U.S. annuls Platt Amendment, 1934 | |

| Batista era, 1934-59 | |

| Pan American Conference (Havana, 1928): U.S. defends interventionism | |

| Haiti | U.S. troops, 1915-34 |

| U.S. financial supervision, 1916-41 | |

| Dominican Republic | U.S. financial supervision, 1905-41 |

| U.S. troops exit, 1924 | |

| Trujillo era, 1930-61 | |

| Puerto Rico | U.S. colony beginning in 1898 |

| Jones Act extends U.S. citizenship, 1917 | |

| Virgin Islands | U.S. colony beginning in 1917 |

Chapter 12 Summary

Chapter 12 introduced Unit IV (Immigration and Latin America) with a historical overview of American imperialism and colonialism to 1945. This background is necessary to understand the relationship of Cold-War American globalism and post-1965 Hispanic immigration, the topic of Chapter 13. Section 12.1 set the stage by discussing the historical linkage between white nationalism and the state/territory distinction in American history.

Section 12.2 reviewed the U.S. nationalistic ideologies of American exceptionalism and manifest destiny, connecting these to 1800s white nationalism.

Section 12.3 described the growth of American empire in the Caribbean and Pacific in the period 1846-1914. Main inflection points of U.S. imperialism were the Mexican War (1846-1848) and the Spanish-American War (1898). The significance of the latter was marking the arrival of the U.S. as a great imperial power in a world dominated by global empires.

Section 12.4 took the discussion to 1945, when the U.S. emerged as the pre-eminent global superpower. The table listed many examples of U.S. intervention in Latin America between 1898-1945. Americans justified military and economic imperialism in terms of Open Door policy.

[1] Left image: Public domain. Right image credit: “Carmen Yulín Cruz, Mayor of San Juan.” CC BY-SA 3.0. Author: Melvin Alfredo (User: Puertorriquenosoy) – Own work.

[2] Likewise, the District of Columbia (population: 689,545), though not a state, has more people than Vermont or Wyoming.

[3] Source: Wikipedia, “List of states and territories of the Unites States by population”: estimated Census populations (July 1, 2020). Accessed 2/8/21.

[4] Source of phrase “empire of liberty”: Wood 2009

[5] Additional comparison cases include the ancient Roman Republic, the French First Republic (1792-95), and the French Third Republic (1870-1940). Cf. De Tocqueville (2003) on monarchy-republic-empire transition.

[6] Thomas Jefferson to John C. Breckinridge, August 12, 1803. “America Past and Present Online – Constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase (1803).” Accessed 7/16/21; boldface added.

[7] Source: Wikipedia, “Oregon.” Boldface added; accessed 7/11/21.

[8] This image, from the Christian New Testament, symbolizes being a moral example to others. Winthrop’s radical Puritan colony—a Christian utopian community—saw itself as a moral example to Anglican England.

[9] Such as the Ostend Manifesto (1854).

[12] Source: Adapted from APAN:II:663

[13] Nicaraguan nationalist leader who fought U.S. Marines (Chasteen 2001:294).