The above image[1] of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. illustrates ongoing obstacles to genuine African American social, political, and economic inclusion, additional to de facto segregation (Chapter 10). The 116th Congress (2019-2021) made headlines as the most diverse in the nation’s history, particularly its freshman class of first-term representatives.[2] Nevertheless, Congress remained dominated by traditionally powerful social groups, in numbers disproportionate to the national population. In particular, non-Hispanic whites, males, Christians, and the wealthy continued to be greatly overrepresented. Regarding gender, of 100 senators, 74 were men and only 26 women. Of 435 House representatives, 334 were men and 101 women (23% women). Yet half of the U.S. population is female.

Regarding race-ethnicity, the Senate remained overwhelmingly white with 91 non-Hispanic whites, but only 4 Hispanics, 2 Blacks, 2 Asians, and 1 multiracial (Black/Asian). The House—somewhat more diverse than the Senate—was 72% white, with 313 non-Hispanic whites (72%), 56 Blacks (13%), 44 Hispanics (10%), 15 Asians, and 4 Native Americans. Such figures indicate the ongoing power of non-Hispanic white Americans as a group, far out of proportion to their actual population numbers. By 2020, about 60% of Americans were non-Hispanic white, in comparison to Hispanic (about 19%) or Black (about 13%). The Black congressional figures highlight both breaks and continuities with the apartheid past. The fact that Black representation in the House (13%) was proportional to the national African American population is a sign of significant racial progress since 1970. Yet the absence of Black senators (3%)—with the Senate being the more powerful and prestigious chamber—underscores ongoing Black political exclusion. Likewise, the small number of Hispanics in Congress points to significant underrepresentation of this group in American politics.

As with elected office, nonwhites in many other settings have frequently had the experience of being “the only one here,” or “we’re the only ones” (McCrummen 2021). Unlike many people of color, few whites have had the regular experience of being the only white person in the classroom, workplace, neighborhood, restaurant, department store, or public park. It can be a lonely experience of powerlessness, isolation, conspicuousness, vulnerability, and anxiety, even if you are technically included.[3] Differing social experiences of whites and people of color suggest many questions: Why do blacks and whites tend to express contrasting group opinions on academic surveys about race relations? How do black-white disparities in criminal justice and health outcomes both reflect and contribute to ongoing de facto exclusion? Faced with ongoing obstacles, how can societies like the United States, Brazil, and South Africa overcome such barriers?

Chapter 11 Learning Objectives

11.1 Racial Injustice Timeline, 1968-2017

- Describe how the 50-year timeline illustrates continuities with apartheid

11.2 Differing Black-White Perspectives and Experiences

- Define double consciousness

- Explain Black English Vernacular’s roots in twentieth-century black social isolation (segregation)

- Describe group differences in black-white perspectives on race relations

11.3 Police Abuse and Mass Incarceration

- Define police abuse

- Define mass incarceration

- Define implicit racial bias

- Understand ongoing racial disparities in policing and criminal justice

11.4 Health Disparities

- Understand ongoing racial disparities in healthcare processes and outcomes

Chapter 11 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

double consciousness: the lived experience of many people of color of seeing themselves simultaneously from two perspectives, nonwhite and white

Black English Vernacular: A version of American English developed by African Americans living for generations in social isolation from European Americans. Aka “the language of segregation.”

integration: racial social mixing, for example in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces. Blacks and whites often have different perspectives on the meaning of “integration.” Whereas blacks on academic surveys often report desiring 50-50 mixing, whites report themselves unwilling to tolerate more than small proportions of blacks. Though the post-Civil Rights era has seen falling levels of principled (de jure) antiblack bias among whites, many whites continue to oppose integration in practice (de facto).

police abuse: a style of policing that emphasizes violence and repression toward civilians, akin to military repression of a conquered population.

racial profiling: a common form of police abuse in Brazil and the United States. Black and brown people in public places are stopped, questioned, and searched far more frequently than are whites. This practice has been so common that the ironic phrase “driving while black” has entered international popular culture.

mass incarceration: the situation of U.S. penal practice since the late 1970s, making America the world’s largest jailer. Not only does the U.S. have the largest absolute prison population in the world, but it incarcerates a higher proportion of its own citizens than any other country. Racial disparities abound in post-Civil Rights mass incarceration.

implicit racial bias: unconscious, antiblack racism. Much social psychological research has shown that people of all racial backgrounds (white, black, other), even those with consciously egalitarian beliefs, commonly display such bias on rapid priming and implicit association tests (Lewis & Diamond 2015:57; cf. Steele 2011).

11.1 Racial Injustice Timeline, 1968-2017

We’ve seen that the purpose of Chapters 9-11 is to explain why most sociologists today see race as a social problem that is largely ongoing, not overcome. Chapter 11 adds to this explanation by discussing sociological conclusions about present-day obstacles—continuities with apartheid, differing black-white perspectives, police abuse and mass incarceration, health disparities—to genuine African American inclusion.

To better understand black group perspectives on race relations (section 11.2 below), it’s important first to appreciate facts about the ongoing nature of racial injustice. Granted, such inequality has changed in many ways since the 1950s-60s Civil Rights era (Anderson 2013). However, the half-century since 1968 has seen not only breaks with apartheid but also continuities. The 50-year timeline below (Table 11.1) lists several types of events: white terrorism, continuities with apartheid, overcoming apartheid, racialized police abuse and police impunity, whitewashing history, and federal retreat from Civil Rights advances. It’s significant that these kinds of events greatly overlap with the post-Reconstruction (1877) era of U.S. history. Accordingly, the timeline further illustrates overall white retreat from genuine racial equality in the post-Civil Rights era (Klinkner & Smith 1999: see Chapter 9). Also note that the timeline is far from exhaustive; many additional events could be added.

Table 11.1. Racial Injustice Timeline (selected events, 1968-2017)[4]

| Year | Event theme | Event |

| 1968 | White terrorism | Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated in Memphis, TN

|

| 1970 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | In Evans v. Abney, U.S. Supreme Court upholds Georgia court’s decision to close rather than integrate Macon’s Baconsfield Park, created by Senator Augustus Bacon [in 1911] for whites only

|

| 1970 | Racialized police abuse | Police shoot and kill two unarmed black student protesters at Jackson State College

|

| 1971 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress

|

President Richard Nixon declares “War on Drugs,” contributing to 700% increase in U.S. prison population by 2007

|

| 1973 | Continuities with apartheid: eugenics | Two young black girls, Minnie (age 14) and Mary Alice Relf (12), sue health clinic in Montgomery, Alabama, for sterilizing them without their knowledge or consent

|

| 1974 | Continuities with apartheid

|

Delbert Tibbs, a black hitchhiker from Chicago, is indicted for capital murder of a white couple in Florida; he is wrongfully convicted by an all-white jury and spends two years on death row

|

| 1976 | Overcoming apartheid | Joseph Woodrow Hatchett is elected Justice of the Florida Supreme Court, becoming the first black person elected to any statewide office in the South since Reconstruction [1877]

|

| 1977 | White terrorism | Newspapers report that Cornell and Geraldine Cook, the only black couple in a white neighborhood in Smithfield, North Carolina, plan to leave after shots are fired into their home

|

| 1980 | Police impunity | After four Miami police officers are acquitted in brutal beating death of Arthur McDuffie, protests leave 23 dead and hundreds injured

|

| 1981 | White terrorism | After a Mobile, Alabama, jury acquits a black man of killing a white police officer, Ku Klux Klan members randomly kidnap and kill 19-year-old Michael Donald, a black man, and hang his body from a tree

|

| 1983 | Racialized police abuse | Chicago police beat, electrocute, and threaten to castrate James Cody; over 100 blacks were tortured by Chicago Police Department over three decades

|

| 1986 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | Anti-Drug Abuse Act creates a 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine possession that contributes to mass incarceration of African Americans

|

| 1986 | White terrorism | Michael Griffith, a 23-year-old black man, is hit by a car and killed after being chased by a white mob in Howard Beach, New York

|

| 1987 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | U.S. Supreme Court upholds death penalty in McCleskey v. Kemp despite proof it is racially biased, reasoning that racial discrimination in the criminal justice system is “inevitable”

|

| 1989 | Continuities with apartheid (Scottsboro Boys, 1931)

|

Five black and Latino teens are arrested for [allegedly] raping a jogger in New York City’s Central Park and spend more than a decade in prison before being exonerated

|

| 1989 | White terrorism | Black teen Yusef Hawkins is accused of visiting a white girl and then is murdered by a white mob in Bensonhurst, New York

|

| 1991 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | In Board of Education of Oklahoma City Schools v. Dowell, U.S. Supreme Court ends federal desegregation order even though it will cause racial re-segregation of school system

|

| 1991 | Racialized police abuse | Severe beating of black motorist Rodney King by Los Angeles police is caught on tape

|

| 1992 | Police impunity | Riots in Los Angeles, California, sparked by acquittal of white police officers who beat black motorist Rodney King, end, leaving 53 people dead, 2,000 injured, and $1 billion in damage

|

| 1994 | Continuities with apartheid | U.S. Department of Justice files suit against school principal in Randolph County, Alabama, who refuses to permit racially integrated prom and bans interracial dating at public high school

|

| 1994 | Continuities with apartheid | Denny’s restaurant chain agrees to pay largest-ever settlement to African Americans who sued after they were refused service, made to wait longer, or charged more than white customers

|

| 1995 | Overcoming apartheid | Mississippi legislature votes to ratify Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, after having rejected it in 1865

|

| 1995 | Continuities with apartheid | Alabama resurrects chain gangs for state prisoners, influencing several other states to do the same

|

| 1995 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | NAACP protests National Park Service’s decision, pressured by Sons of Confederate Veterans and Sen. Jesse Helms, to uncover “faithful slave monument” at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia

|

| 1995 | Racialized police abuse | Five police officers in suburban Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, kill black motorist Jonny Gammage during a routine traffic stop by pinning him face down on the pavement until he asphyxiates

|

| 2000 | Overcoming apartheid | Alabama repeals 1901 state constitutional ban on interracial marriage, although a majority of white voters favor keeping the ban

|

| 2001 | Continuities with apartheid | Harvard University’s Civil Rights Project releases study finding that schools were more segregated in 2000 than they were in the 1970s before desegregation efforts, including busing, began

|

| 2004 | Continuities with apartheid | Alabama voters reject constitutional amendment that would remove from state constitution a provision requiring separate schools for “white and colored children”

|

| 2005 | Overcoming apartheid | U.S. Congress formally apologizes for its failure to pass any of the 200 anti-lynching bills introduced from 1882 to 1968

|

| 2005 | Continuities with apartheid | Hurricane Katrina: the subsequent disaster response is criticized for mistreating many severely impacted black citizens

|

| 2006 | White terrorism | David Ritcheson, a Latino 16-year-old who was brutally beaten and sexually assaulted after trying to kiss a white girl at a party in Texas, testifies before Congress in support of hate crime laws

|

| 2006 | Impunity for past white terrorism | Nearly 55 years after civil rights activists Harry and Harriette Moore were killed by a bomb, a renewed investigation finds four now-deceased Ku Klux Klansmen were responsible

|

| 2007 | Overcoming apartheid | Turner County High School in Ashburn, Georgia, holds first racially integrated prom; in prior years, parents had organized private, segregated proms for white and black students

|

| 2007 | Continuities with apartheid | Up to 15,000 people in Jena, Louisiana, protest the attempted murder prosecution of six black teens for fighting with white students who hung a noose from a tree on their high school campus

|

| 2009 | White terrorism | Members of the Ku Klux Klan burn a cross in an African American neighborhood in Ozark, Alabama, to intimidate black residents

|

| 2009 | Continuities with apartheid | Justice of the peace in Louisiana refuses to marry an interracial couple because of their race and later acknowledges he denied marriage licenses to interracial couples for years

|

| 2010 | Continuities with apartheid | Civil rights activist lawyers argue to overturn the death-in-prison sentence [life sentence] imposed on a 13-year-old child in Mississippi

|

| 2010 | Whitewashing history | Alabama prison officials ban all prisoners from reading Slavery by Another Name, a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the “re-enslavement” of African Americans during Jim Crow era

|

| 2010 | Racialized police abuse, relative impunity | Police officer Johannes Mehserle is sentenced to two years for fatally shooting black 22-year-old Oscar Grant III in the back while he was face down on an Oakland, California, train platform

|

| 2010 | Impunity for past white terrorism | Former police officer James Bonard Fowler pleads guilty to 1965 murder of civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson in Marion, Alabama, and is sentenced to six months in jail

|

| 2011 | Immigration and race | Alabama legislature passes anti-immigrant law designed to force immigrants to flee the state; Governor Robert Bentley later signs it despite language that legalizes racial profiling

|

| 2011 | Continuities with apartheid: racialized poverty

|

[2010] U.S. Census reports 25.7% of African Americans and 25.4% of Hispanic Americans are living below the federal poverty line, compared to less than 10% of white Americans

|

| 2011 | White terrorism | White teens kill James Craig Anderson, a black man, in a hate crime in Jackson, Mississippi

|

| 2012 | Continuities with apartheid | Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black boy, is killed in Sanford, Florida; police arrest shooter George Zimmerman only after national outcry against claim that Stand Your Ground law barred his prosecution

|

| 2012 | State-level commitment to Civil Rights progress

|

First decision under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act finds that racial bias infected Marcus Robinson’s capital trial 18 years earlier [1994] and commutes his death sentence to life without parole

|

| 2012 | Overcoming apartheid: eugenics | North Carolina legislators recommend $50,000 compensation for victims of forced sterilization program from 1930s to 1970s; 60% of women sterilized against their will were black

|

| 2012 | Continuities with apartheid | Report shows one of every 13 voting-age African Americans is disenfranchised [7.7%] (four times more than non-black citizens); Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia bar over 20% of black residents from voting

|

| 2012 | Continuities with apartheid: black criminalization | U.S. Justice Department files civil rights lawsuit against Meridian, Mississippi, officials for incarcerating black and disabled children for dress code violations and talking back to teachers

|

| 2013 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress | Alabama officials argue before U.S. Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder that Voting Rights Act of 1965’s protections are no longer needed to prevent discrimination; on June 25, the Court agrees

|

| 2013 | State-level retreat from Civil Rights progress

|

North Carolina House votes to repeal Racial Justice Act, ending remedy for racial bias in capital trials

|

| 2013 | Continuities with apartheid: criminal justice

|

Kimberly McCarthy is 500th person executed by Texas since 1972; more than half [50%] of those executed have been people of color

|

| 2013 | Continuities with apartheid: eugenics | Center for Investigative Reporting breaks story this week that State of California improperly sterilized nearly 150 incarcerated women between 2006 and 2010

|

| 2013 | Continuities with apartheid: criminal justice

|

Federal district court rules New York Police Department’s “stop and frisk” policy is discriminatory and unconstitutional upon finding that 85% of people stopped are black or Hispanic

|

| 2013 | Federal retreat from Civil Rights progress

|

Federal court in Alabama upholds…redistricting plan that reduces black voting power

|

| 2014 | Overcoming apartheid symbolism | Federal appeals court rules Texas must issue group license plate for Sons of Confederate Veterans that features a Confederate flag; United States Supreme Court later reverses this decision

|

| 2014 | Continuities with apartheid | Black workers at Memphis, Tennessee, cotton gin file discrimination lawsuit after white supervisor uses racial slurs and threatens to hang them for drinking from “white” water fountain

|

| 2014 | Racialized police abuse | Eight days after graduating from high school, black teenager Michael Brown is shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, sparking protests and outcry nationwide

|

| 2014 | Racialized police abuse | Tamir Rice, a black 12-year-old boy, dies after being shot by police while playing with a toy gun in a park near his home in Cleveland, Ohio

|

| 2015 | Racialized police abuse, continuities with apartheid | U.S. Department of Justice finds pervasive racial bias within police department and municipal court in Ferguson, Missouri, including targeting black people for stops, arrests, and uses of force

|

| 2015 | Continuities with apartheid | San Francisco police officers’ racist text messages referencing cross burning and lynching are released to news media

|

| 2015 | Continuities with apartheid | Protesters march after University of Oklahoma’s Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity is taped singing a song that includes the n-word and “You can hang him from a tree, but he’ll never sign with me.”

|

| 2015 | Continuities with apartheid symbolism | Nine states, including Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia, recognize Confederate Memorial Day as an official state holiday to commemorate the surrender of the Confederate army in April 1865

|

| 2015 | White terrorism | In Charleston, South Carolina, white teen who embraced racist ideology and wanted to start a “race war” is arrested for shooting nine black people attending Bible study at Emanuel A.M.E. Church

|

| 2015 | Continuities with apartheid symbolism

|

After discussing the need to protect Confederate memorials, North Carolina’s House passes bill requiring legislative approval to remove historical monuments; the bill is signed into law days later

|

| 2015 | Whitewashing history | Despite public outrage over a Texas history textbook that depicted enslaved people as “workers from Africa,” state lawmakers reject proposal to require that textbooks be fact-checked

|

| 2016 | Racialized police abuse, impunity | Grand jury in Arlington, Texas, refuses to indict Brad Miller, a white police officer who fatally shot unarmed, 19-year-old black college student and football player Christian Taylor in August 2015

|

| 2016 | Racialized police abuse | Baton Rouge, Louisiana, police officers shoot and kill Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old black man, while he is pinned to the ground; video of the shooting leads to major protests nationwide

|

| 2016 | Racialized police abuse | Days after shooting black therapist Charles Kinsey and handcuffing him as he lay bleeding on the ground, police in North Miami, Florida, claim officer was aiming for Dr. Kinsey’s unarmed autistic patient

|

| 2016 | Whitewashing history | First Lady Michelle Obama’s speech acknowledging “I wake up every morning in a house built by slaves” sparks backlash

|

| 2016 | Racialized police abuse, impunity | St. Anthony, Minnesota, police officer Jeronimo Yanez returns to duty before completion of the investigation into his fatal shooting of Philando Castile weeks earlier

|

| 2017 | White terrorism | White nationalists protest removal of a Confederate statue in Charlottesville, Virginia; the next day, a protester drives a car into counter-protesters, injuring 19 and killing one woman. The car driver was a twenty-year-old man who had driven from Ohio, and had previously espoused neo-Nazi and white supremacist beliefs

|

11.2 Differing Black-White Perspectives and Experiences

In many ways, white and black Americans share the same society, with a common culture, history, government, economy, etc. However, these racial groups also have a long, ongoing history of social distance, as measured by indicators like low intermarriage and high residential segregation (Telles & Ortiz 2008:158). Social distance has contributed to significant black-white contrasts in group attitudes about race relations, as studied by academic survey researchers (Schuman et al. 1997). These differing perspectives have endured to the present, long after apartheid’s formal end by 1968.

Relevant here is a longstanding theme in African American culture: double consciousness (Du Bois 1903; Gates & McKay 1997). This is the lived experience of many people of color (and colonized peoples worldwide) of seeing themselves simultaneously from two perspectives, nonwhite and white (Glissant 1990:17). Fragmented, colonized consciousness can feel like participating in two “worlds,” with two distinct sets of meanings, values, and allegiances (Fanon 1967; Lamming 1991:xxxvii; La Vega 2006; Rawls 2000). Fractured or double consciousness involves internalization by marginalized social groups—e.g., blacks, women, the poor, gays—of hegemonic social values. The oppressor’s (colonizer’s, master’s) voice becomes an internal voice of conscience leading to self-abasement in favor of the normalized group: e.g., whites, men, the middle class, heterosexuals (Condé 1992; Kincaid 1997). In this and other ways, the black world(s) can feel different from the white world(s). Today, important contrasts remain between black/brown society and white society in countries like Brazil, Colombia, South Africa, and the United States. Many people of color continue to find that “double consciousness” chimes with their own experience (Rawls & Duck 2020).

A telling example of ongoing black-white social distance is Black English Vernacular, as compared to Standard American English. Twentieth-century social isolation of blacks—segregated from whites in housing, education, work, leisure, religion, marriage, etc.—was so extreme and enduring as to create contrasting versions of the English language. Sometimes called “the language of segregation,” U.S. Black English Vernacular is analogous to Black Creole languages in the Caribbean—complex idioms of daily life capable of sophisticated and literary expression (Chamoiseau 1999). By contrast, whitening of white ethnic groups by the 1960s resulted in Standard American English (see Chapter 7). White Americans—whether of Irish, German, Italian, Hungarian, Polish, or Jewish ancestry—spoke a version of English characterized by a single set of linguistic norms, featuring key grammatical and lexical differences from the English spoken by many African Americans (Massey & Denton 1993:162-63).

Differing black-white perspectives. Post-1968 survey and ethnographic findings on race relations should be understood in terms of ongoing black-white social distance (Telles & Ortiz 2008:158). Below, we review four themes: (1) race relations, racial change, integration; (2) slavery apology and slavery reparations; (3) ongoing anti-black stereotypes; and (4) the race representative.

(1) Race relations, racial change, integration. One consequence of twentieth-century black social isolation is contrasting black-white views on race relations and racial progress (Bonilla-Silva 2018; Schuman et al. 1997). Opinion polls in recent years continue to show marked differences in the outlooks of the two racial groups. Whereas the majority of whites report optimism on U.S. race relations today and in the future, the majority of blacks report pessimism (Feagin 2020:239). For example, whereas 59% of blacks say their view of contemporary black-white race relations is negative, only 45% of whites report a negative view. On the future of racial change, a national 2019 Pew Research Center poll found that most blacks (78%) saw the nation’s efforts to secure black equal rights as insufficient; by contrast, just 37% of whites agreed. Moreover, 50% of blacks viewed U.S. racial equality as unlikely to ever be achieved, whereas this view was rare (7%) among whites (ibid).

Likewise, black-white perspectives have long differed on the meaning of racial integration. For example, the 1976 Detroit Area Survey on residential segregation found that the word “integration” meant different things to Detroit blacks and whites (Massey & Denton 1993:93). Whereas for blacks it meant neighborhoods between 15% to 70% black (with 50% being most desirable), for whites it meant far fewer blacks. The Detroit findings were later replicated by academic surveys in Los Angeles, Kansas City, Cincinnati, Omaha, and Milwaukee. In all these northern and western cities, whites reported themselves unwilling to live in integrated neighborhoods with more than 20% blacks (ibid).

Such attitude differences (post-1970) echo similar black-white contrasts during the Civil Rights era itself. During the 1940s-60s, many whites, both South and North, expressed ambivalence or disapproval of federal action on civil rights. In 1964—under intense pressure from the black civil rights movement, white fears of black rioting, and Cold-War era international scrutiny of American racism—Congress passed the most far-reaching civil rights act in U.S. history. However, a 1963 national poll found that almost two-thirds (64%) of white Americans saw blacks as moving “too fast” to achieve equality (Klinkner & Smith 1999:275, 396). Similarly, a 1964 poll found most white Americans (70%) opposed to blacks having more influence in government (ibid:275). By October 1966, 85% of all white Americans viewed blacks as moving too fast to achieve equality (ibid:280).

In sum, during the 1960s most whites—North, South, West—opposed immediate action (public policy) on civil rights. There was never a 1960s white consensus in favor of full social and political equality for African Americans. Rather, the 1960s was a time of marked U.S. political polarization, with one of the major controversies (among whites) being black civil rights. Today’s black-white attitude differences on race relations reflect this long history of white ambivalence to genuine black equality.

(2) Slavery apology, slavery reparations. The United States has never officially apologized or offered redress or reparations for African American slavery (Harvey 2007:156). By contrast, in 1988 the U.S. government—responding to sustained pressure by Japanese American advocacy groups—acknowledged and apologized for WWII internment camps, offering financial redress to surviving victims (see Chapter 6).[5]

White resistance to slavery apology says much about the ongoing significance of blackness in the post-Civil Rights era (Feagin 2020). This theme further illustrates differing black-white perspectives. For example, a 1997 ABC News poll found that most white respondents (66%) saw U.S. government apology for slavery as unnecessary, with 88% opposing reparations for slavery. In stark contrast, 66% of black respondents viewed government apology and reparations as necessary (Harvey 2007:228).

(3) Ongoing anti-black stereotypes. After 1970, many whites continued to hold biased and stereotypical views of African Americans. In nationally representative academic surveys, whites continued to report beliefs that blacks are more violent than whites and fail to maintain their homes and lawns. Such stereotypes fueled worries that neighborhood integration would increase crime rates and lower property values of houses (Massey & Denton 1993:95). Although white beliefs in biological black inferiority decreased after 1970, many academic surveys have found that whites continue to blame black poverty, limited education, mass incarceration, and poor health not on white supremacy but rather on inferior black culture and morality (Lewis & Diamond 2015:149). Many white Americans report being more intelligent and working harder than blacks, and view ongoing black-white disparities in life chances as due to lack of motivation among blacks (ibid).

Color-blind ideology claiming that racism is no longer a social problem has allowed whites to explain away such anti-black bias as “not racist.” Accordingly, a further black-white contrast in perspectives is differing definitions of racism. After 1970, it was primarily powerful whites (e.g., Supreme Court justices) who decided what legally counted as racism: individual prejudice (biased intentions or motives), not white normativity (Flagg 1993). But “[a]s white people are not the target of racism in white institutional spaces, they are the least likely group of people…to understand how racism works” (Moore 2008:176). Individual-level definitions have often failed to reflect black experiences of exclusion (Bonilla-Silva 2018; Steele 2011).

(4) The race representative. This theme appears prominently in sociologist Adia Wingfield’s (2013:119) interviews with black professional men. These are lawyers (in law firms), engineers (in engineering departments), doctors (in hospitals), and bankers (in banks). These men, often virtually the only African Americans in their peer group at their institutions, often perceive themselves as cast in the role of symbolizing or embodying their institutions’ “commitment to diversity.” Being repeatedly asked to volunteer their time and labor at events where they represent their institutions’ diversity can significantly detract from normal job responsibilities and thus harm job performance and evaluation (ibid:120).

Overall, the four themes illustrate differing black-white experiences and perspectives on race relations. Much interracial dialogue continues to be needed if Americans are to overcome this obstacle to genuine black inclusion.

11.3 Police Abuse and Mass Incarceration

As during apartheid, American criminal justice and law enforcement remained key obstacles to genuine racial inclusion in the post-Civil Rights era (Gonzalez Van Cleve 2016). Below, we examine two areas: police abuse and mass incarceration.

(1) Police abuse. The timeline above (Table 11.1) indicates the ongoing problem of racialized police abuse (Telles 2004). Whereas alternative styles of policing promote good relations with marginalized community members, this style emphasizes violence and repression akin to military occupation of a conquered population (Alexander 2010). Such abuse has often targeted vulnerable groups such as nonwhites, the poor, homosexuals, immigrants, the mentally ill, and the homeless. Police brutality resulting in civilian injury or death has been a common means of repressing nonwhites in Brazil, South Africa, the United States, and many other societies with long histories of racial inequality (Telles 2004:166ff). In Brazil, for example, black and brown people—whether poor, working class, or middle class—have long been police targets, at rates disproportionate to whites of the same economic classes (ibid:167-168).

A common form of police abuse in Brazil and the U.S. has been racial profiling (Desmond & Emirbayer 2010). Black and brown people in public places (e.g., walking, shopping, driving cars) are stopped, questioned, and searched far more frequently than are whites (Telles 2004:168). This practice has been so common that the ironic phrase “driving while black” has entered international popular culture

In the U.S., important Supreme Court rulings since 1968 increased the likelihood that racialized police abuse would continue in the post-Civil Rights color-blind legal environment. For example, Terry v. Ohio (1968) increased police powers to stop-and-frisk, lowering the requirement for stopping a civilian from “probable cause” to “reasonable suspicion” of criminality. Police discretion, despite official color-blindness, continued to rely on race in making such stops. Graham v. Connor (1989) applied an “objective reasonableness” standard to officers’ actions, which encouraged police use of deadly force. Whren v. U.S. (1996) allowed racial profiling by police via “pretext” traffic stops (Alexander 2010). Thus, despite de jure color-blind rules, U.S. policing is often not color-blind in de facto practice (Bonilla-Silva 2018).

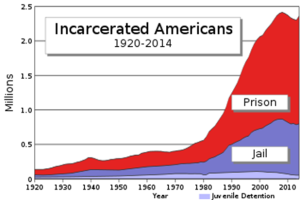

(2) Mass incarceration. Since the mid-1970s, changes in U.S. penal practices have led to racialized mass incarceration, making America the world’s largest jailer. Not only does the U.S. have the largest (in absolute numbers) prison population in the world, but it incarcerates a higher proportion of its own citizens than any other country. For example, about 1 out of every 100 U.S. adults (1%) was in jail or prison in 2008. This figure—extraordinarily high as compared to the pre-1980s United States—was far greater than imprisonment rates in Russia, Canada, or Japan. Since the 1970s, the incarceration rate of U.S. women has ballooned by 7 times (APAN:II:891).

Figure 11.1. Total U.S. incarceration by year.[6]

Black-white incarceration disparities during the Civil Rights era (1950s-60s)—already large—worsened dramatically in the post-Civil Rights decades. In the 1950s, African Americans formed only 10% of the U.S. population, yet comprised 33% of U.S. prisoners (Telles 2004:169). By the 1990s this disparity had greatly increased, with blacks (by then 12% of the U.S. population) comprising 50% of all state and federal prisoners. The chances of blacks being incarcerated were 7 to 8 times greater than for whites in the 1990s (ibid). In the 1990s, between 25% and 33% of the nation’s entire population of young black men was under the control of the criminal justice system in some form (e.g., jail, prison, or parole: Klinkner & Smith 1999:337). By 2010, black men remained 7 times more likely than white men to be incarcerated (APAN:II:891). Although the overall U.S. incarceration rate began to dip after 2008, the nonwhite proportion of inmates continued to increase (Hohle 2018:229). By 2013, non-Hispanic whites—comprising about 60% of the U.S. population—were just 33% of the prison population. By contrast, blacks—only 12% of all Americans—formed a whopping 36% of all prisoners (ibid).[7]

Such numbers show that U.S. racial disparities in imprisonment greatly worsened after apartheid’s end. Post-1970 black-white differences were especially due to drug-related crimes: specifically, how government and police pursued the War on Drugs (Alexander 2010). Though blacks and whites used illegal drugs at about the same levels, arrest and conviction of blacks was much more likely than for whites (Telles 2004:169).

Mass incarceration has had disastrous consequences for black political participation and representation, one of the priorities of the Civil Rights movement (Morris 1986). This is especially due to the fact that many states have prohibited felons and ex-prisoners from voting (Alexander 2010). In any given year, a sizeable portion of all U.S. black males was disfranchised by criminal convictions; for example, in 1999 this figure was 13% (Klinkner & Smith 1999:342). By contrast, the prison boom created a new source of income for many whites (and some nonwhites). Federal and state politics led to prisons being constructed in economically stagnant rural white regions, bringing jobs of many types: e.g., construction workers, corrections officers, wardens, social workers, supervisors (Hohle 2018:207). Moreover, the post-Civil Rights era saw the takeoff of the corrections industry: private prisons in the business of incarceration. The nation’s first for-profit prison corporation—Correctional Corporation of America (CCA)—was established in 1983 in Tennessee (ibid:208-209).

Finally, implicit racial bias—largely unconscious anti-black racism—has been especially damaging in associating black males with “inherent” criminality. As discussed above, after 1970 many whites continued to hold biased and stereotypical views of African Americans. Such racial bias has contributed to black-white disparities at all stages of the criminal justice processing funnel: from apprehension, arrest, and jail to trial, sentencing, and imprisonment. Much social psychological research has found implicit, antiblack bias in the day-to-day activities of a host of participants in criminal justice, not only whites but also blacks and others (Lewis & Diamond 2015:57; cf. Steele 2011).

In many ways, then, racial inequalities abound in contemporary criminal justice and law enforcement. Many observers point to racialized mass incarceration as playing a key role in post-Civil Rights white retreat from commitment to racial equality (Alexander 2010; Bonilla-Silva 2018). Certainly, mass incarceration is a major source of differing black-white experiences and perspectives in the post-Civil Rights era. In 2021 on any given day, 10% of all American black men in their thirties were in prison or jail. In 2021, two-thirds (66%) of U.S. juvenile detention consisted of youth of color.[8] The huge racial disparities of such figures illustrate the big picture: the extremely disparate impact, as compared to whites, of mass incarceration on people of color and their communities.

11.4 Health Disparities

The COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020 revealed disparities in African American death rates as compared to whites.[9] Such inequalities are only the most recent example of a long history of black-white differences in medical and healthcare processes and outcomes.

Racialized health disparities represent yet another ongoing obstacle to genuine black inclusion. In the post-Civil Rights era, measures of American health (e.g., health status, healthcare access and outcomes) continued to indicate racial-ethnic inequalities, as hundreds of research studies have shown (Sanchez & Ybarra 2013:104; cf. Cristancho et al. 2008; Flores 2006). Part of the explanation is that a higher proportion of blacks than whites are poor. For example, in 1990 “[i]n Central Harlem, note[d] the New York Times, the infant death rate…[was] the same as in Malaysia. Among black children in East Harlem, it…[was] even higher: 42 per thousand, which would be considered high in many Third World nations” (Kozol 1991:115).[10]

As with any racial group, black life chances regarding health appear to be shaped by the interaction of race and class. Like Native Americans, the high rate of African American poverty contributes to overall low health outcomes as compared to whites. An example is life expectancy: in 2013, white Americans could expect to live (on average) for 78.3 years, whereas for black Americans this figure was 73.1 years (Gómez & López 2013:3). Moreover, health disparities are not only physical, but also show up in mental health status and treatment (Helms & Mereish 2013:146).

In addition to economic class, other important factors in the social context of healthcare appear to contribute to racial disparities. One is de facto residential segregation. For example, in 2013, although the likelihood of getting breast cancer was slightly higher in Chicago for white women than for black women, women in the latter group were two times as likely to die from it (Gómez & López 2013:4-6). As we’ve seen (Chapter 10), post-Civil Rights Chicago remained highly segregated by race. On average, women in black neighborhoods had to travel farther than white women to get mammograms, making it less likely they would get them regularly, let alone mammograms with up-to-date equipment and trained staff (ibid). Another social factor is the experience of antiblack discrimination. The stresses of dealing with actual and anticipated racism—regular occurrences both in daily life and in the healthcare system—appear to further contribute to black-white health differences (Kahn 2013:25).

As in education and criminal justice, implicit racial bias has frequently operated in healthcare. Much social psychological research has shown that people of all racial backgrounds (white, black, other) with consciously egalitarian beliefs, nevertheless frequently display such bias on rapid priming and implicit association tests (Lewis & Diamond 2015:57; cf. Steele 2011). For instance, in a 2007 study, doctors took an implicit association test of positive or negative psychological associations with blacks and whites. The doctors with the most antiblack associations were less likely to use a heart-attack-preventing medicine with a hypothetical black patient complaining of chest pain, as compared to doctors with more positive black associations (Lewis & Diamond 2015:195).

Consider the following series of common healthcare practices (Table 11.2). In each area, implicit antiblack bias by clinicians (of a variety of racial-ethnic identities) remains all too common.

Table 11.2. Implicit Racial Bias in Healthcare[11]

| Area of Bias

|

Description of Common Anti-Black Practice |

| Pain | Clinicians systematically undertreat black and brown patients for pain, as compared to white patients. This practice is rooted in the longstanding medical myth that blacks are less sensitive to pain than are whites.

|

| Heart | In judging the safety of heart surgery, clinicians assign higher risk values to black patients, relative to white patients. That is, clinicians take greater risks with black surgeries than with white ones. This differential treatment is an example of a race-based “correction” in clinical diagnosis, electronic health records, and machine learning algorithms. Such corrections are frequently based on assumptions about different health characteristics between blacks and whites.

|

| Lungs | Spirometry measures patient exhalations (force, volume) and lung capacity, to determine if these fall within a normal range. Measures are adjusted downward for groups shown to have lower lung capacity—e.g., shorter or older patients. But such corrections are also made for blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Contemporary “race” correction in spirometry shows the ongoing influence of the longstanding medical myth that whites have more lung capacity than blacks, and thus that blacks would benefit more than whites from low-skill, manual labor.

|

| Kidneys | Race correction results in fewer black patients being diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, as compared to white patients. Another result is fewer blacks becoming eligible for kidney transplants.

|

| Medical Education | Clinicians learn racially disparate medical practices involving race correction in their medical training. Yet the evidence justifying such practices is far from clear, and at times relies on longstanding antiblack stereotypes rooted in white supremacy.

|

Chapter 11 and Unit III Summary

Chapter 11 discussed ongoing obstacles to genuine African American inclusion, additional to those presented in Chapter 10. Section 11.1 used a timeline to illustrate continuities with apartheid in the post-Civil Rights era. The timeline contextualized the rest of the chapter discussion.

Section 11.2 discussed contrasting black-white experiences and perspectives, rooted in twentieth-century apartheid. One major continuity with apartheid is ongoing black-white differences in attitudes on race relations. Such findings should be interpreted in relation to ongoing social distance (low intermarriage, high residential segregation) between the two groups.

Section 11.3 reviewed police abuse and mass incarceration as continuing obstacles to black inclusion. The U.S. has been the world’s largest jailer since the late 1970s, with nonwhites forming an extremely disproportionate component of the U.S. population under the control of the criminal justice system (jail, prison, parole).

Section 11.4 introduced ongoing black-white health disparities as another obstacle to inclusion. On many measures of physical and mental health, blacks have poorer outcomes than do whites. There has been much recent research on the social context of disparities, and on racist assumptions and implicit racial bias in medical treatment of nonwhites.

Overall, Unit III examined American legacies of racialized slavery. Historical and comparative (international) perspectives with Brazil and South Africa complemented the present-day U.S. focus. Unit III reviewed diversity-relevant aspects of Reconstruction and American apartheid, historical and comparative perspectives on the post-Civil Rights era, and a series of ongoing obstacles to genuine African American inclusion.

[1] Image credit: Creative Commons license (“US Capitol” by Mark Fischer is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

[2] Source of all Congress facts here and below: Wikipedia, “116th United States Congress.” Accessed 9/27/21.

[3] The same can be said about women in otherwise all-male groups or settings.

[4] The table focuses on events in the South. Source: Adapted from Equal Justice Initiative 2019 Calendar: “A History of Racial Injustice.” https://eji.org/

[5] National Archives website, accessed 3/14/21. https://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/redress#:~:text=The%20Office%20of%20Redress%20Administration%20(ORA)%20was%20established,of%20Japanese%20Americans%20during%20World%20War%20II%20(WWII)

[6] Image: Public domain. Source: Wikipedia, “Incarceration in the United States.” Accessed 5/28/21.

[7] Hohle’s source is U.S. Department of Justice, “Prisoners in 2013.”

[8] Source: The Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/issues/racial-disparity. Accessed 5/11/21.

[9] See CDC: “Introduction to COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities” (updated December 10, 2020; accessed 7/13/21). www.cdc.gov/

[10] CREDIT LINE: Excerpt(s) from SAVAGE INEQUALITIES: CHILDREN IN AMERICA’S SCHOOLS by Jonathan Kozol, copyright © 1991 by Jonathan Kozol. Used by permission of Crown Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

[11] Source: Adapted from “Field Correction” by Stephanie Dutchen. Harvard Gazette, Spring 2021. https://hms.harvard.edu/magazine/racism-medicine/field-correction?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Daily%20Gazette%2020210127%20(1)