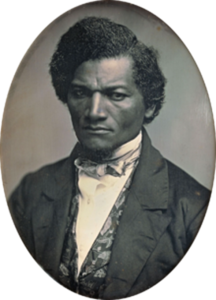

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), a powerful critic of American slavery and white supremacy, was one of the greatest African American leaders of the nineteenth century.[1] Born enslaved in Maryland, his mother was a black slave. His father, a white man, was probably her owner (Douglass 2017:2-3). After escaping to Massachusetts, the fugitive (whose freedom was later purchased by anti-slavery friends) soon became a famous abolitionist orator and author.

The image above illustrates American social criticism, motivated by the need to overcome complacency about significant contradictions or gaps between national ideals and realities. What is social criticism’s important role in promoting democracy in open societies, as opposed to closed, authoritarian societies? Why does such criticism nevertheless often encounter strong opposition? How can empirical, social scientific research complement and support social criticism? What is the role of criticism in learning about racial and ethnic diversity?

Chapter 2 Learning Objectives

2.1 Reflexivity

- Define and describe reflexivity

- Explain the relationship between reflexivity and social criticism

2.2 Social Criticism in Open Societies

- Describe the role of social criticism in holding society accountable to its claimed values

- Explain how the U.S. currently falls short on international measures of democracy

- Define ideology

2.3 Repression and Social Criticism in Action

- Define McCarthyism

- Understand Frederick Douglass’ use of social criticism in the service of democratic values

2.4 “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”: Discussion of Douglass’ Speech

- Demonstrate awareness of connections between Douglass’ nineteenth-century abolitionist career and social criticism today

Chapter 2 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

Frederick Douglass: (1818-1895), abolitionist critic of American slavery and one of the greatest African American leaders of the nineteenth century. His 1852 abolitionist speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” has great relevance to social criticism today.

reflexivity: self-awareness of how our social identities influence our everyday experiences

American Dream: an ideology stating that the U.S. offers economic, political, educational, and cultural opportunities accessible to most citizens and immigrants

full democracies: “nations where civil liberties and fundamental political freedoms are not only respected but also reinforced by a political culture conducive to the thriving of democratic principles”

flawed democracies: “nations where elections are fair and free and basic civil liberties are honored but may have issues (e.g., media freedom infringement and minor suppression of political opposition and critics)”

ideology: the political worldview of a social group—whether a nation, a social movement, a political party, a religion, or a socio-economic class

McCarthyism: extreme anticommunism in the early Cold War. Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy led highly publicized “witch hunts” of alleged Communists in American government and industry.

2.1 Reflexivity

Our social identities matter for how we experience society and formulate (or don’t) criticisms of it. For example, the fact that Frederick Douglass was born and grew up as an African American slave in 1820s-30s Maryland thoroughly shaped his views on controversial political topics of his day such as slavery and abolitionism. By contrast, his white owners were masters, not slaves: this fact of social identity likewise deeply shaped their political views.

Who we are influences what we experience (and don’t experience). Accordingly, most sociologists argue that—rather than conceal these inevitable personal influences on their scientific observations—they should acknowledge them. Sociologists develop their reflexive self-awareness about how their personal experiences and views may influence or bias their observations of society. Also, it often makes sense for sociologists to communicate to their audiences something of this self-awareness. Scientists have sophisticated techniques for limiting sources of potential bias in data—and thus social scientific observations typically differ from commonsense observations. Nevertheless, it isn’t possible for human beings, even scientists, to attain a purely objective “view from nowhere” (Rorty 1979).

For example, paleontologist and biologist Stephen Jay Gould (1996) noted that objectivity is best defined as fair, balanced treatment of evidence and data, rather than absence of preference. Scientists inevitably have preferences about various theories, and must understand such biases in order to treat evidence fairly (36). Indeed, despite their crucially important role in human knowledge, natural science and mathematics are grounded in social values. These include objectivity, intellectual/logical consistency, reason over appeal to authority, the search for truth as worthwhile, publicly verifiable evidence over intuition, knowledge over contentment not to know, etc. Scientists’ work practices show how much they care about these ideals, with good science approximating them more closely than bad science. Such values—not held by all social groups—help make science what it is as a distinctive social activity.

Beyond this overall agreement about reflexivity, however, sociologists have many different ideas about the social background of science. Reflexivity is a complicated subject, with many implications and facets. Pierre Bourdieu, one of the most important conflict-theory sociologists of the past fifty years (see Chapter 1), offered an influential definition of reflexivity as the inclusion of a theory of intellectual practice within sociological theory (Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992:36). That is, theories of society must include self-awareness of how they are created, applied, and tested.

Similarly, for our purposes we can define reflexivity as: self-awareness of how our social identities influence how we experience everyday life. It is consciousness of the relationship between one’s social identities and one’s perceptions and actions. Reflexivity is an especially important habit for students and teachers of diversity. Indeed, a major goal of this textbook is to develop your awareness of how your social identities—your gender and sexuality, socioeconomic class, race and ethnicity, nationality, citizenship status, age, religion, etc.—influence your ideas and feelings about diversity. Sociology offers many insights into the relationship between one’s personal experiences or troubles, on the one hand, and public issues, on the other (Mills 1959).

For these reasons, as the textbook’s author, I want to share with you a bit about myself, to offer further insight into why I think diversity education is important and how my life circumstances have shaped this view. My name is Matt Hollander. I’m a middle-aged, non-Hispanic white man from the Midwest. I’ve taught many diversity and sociology courses at Marion Technical College in Ohio (as full-time faculty) and at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (as a graduate student). I moved to Ohio with my wife from Wisconsin in 2019 to start teaching sociology at MTC. Before that, I finished my Ph.D. in sociology in 2017 at UW, and then worked as a post-doctoral researcher in the UW Department of Emergency Medicine, where I contributed to several research projects on community paramedicine and dementia caregiving.

At UW, I taught many undergraduate sociology classes, including sociological theory, statistics, criminology, and introduction to sociology. I also got married in 2017. (I guess that was a big year for me!) My wife—who has two master’s degrees (Spanish and Portuguese; Latin American and Caribbean Studies)—hails from Sonora, the Mexican state just south of Arizona. I have a strong interest in Mexican history and culture, working hard in recent years on my Spanish. I also enjoy playing jazz guitar (big fan of jazz), an art form rooted in African American culture.

As you can imagine, key features of my social identity (e.g., being male, cisgender, non-Hispanic white, Midwestern, middle class, heterosexual, married to a Mexican immigrant) have shaped in many ways my life experience, and what I’ve not experienced. My multifaceted identity has colored my outlook on the world, and certainly on racial-ethnic diversity. What role has your own identity played in your life, and how you think and feel about diversity and other political issues?

2.2 Social Criticism in Open Societies

There are many admirable features of the United States and its republican, democratic, open social institutions: work and economy, politics and governance, education, culture, civil and criminal law, etc. Why else would immigrants today continue, as in the past, to be willing to endure sacrifices (sometimes even risking their lives) to come here? The U.S. features economic, political, educational, and cultural opportunities that amount to an American Dream that many people in many countries wish for.

However, American society has embodied this ideal to different degrees at various points in its history. Democracy has been stronger or weaker in different eras of U.S. history. One example is Reconstruction (1865-1877) and the Gilded Age (1877-1900). Though eras of mass immigration, they also featured rampant corruption in politics and business, which often included members of Congress and at times reached into the White House. Democratic ideals were often hard to find in the U.S. of the late 1800s, and something similar could be said about the nation in the early 2000s.

Today, the search for democratic opportunities might more accurately be termed the “Norwegian Dream” or the “Canadian Dream” than the “American Dream.” Currently, the most respected non-partisan measures of democracy rank the U.S. as #25 in the world (see below). Among the overall categories (“full democracy,” “flawed democracy,” “hybrid regime,” and “authoritarian government”), the U.S. is currently a “flawed democracy.” By contrast, comparable developed countries like Canada (#5), Australia (#9), and the United Kingdom (#16), are all “full democracies”:

“Full democracies [like Canada #5] are nations where civil liberties and fundamental political freedoms are not only respected but also reinforced by a political culture conducive to the thriving of democratic principles. These nations have a valid system of governmental checks and balances, an independent judiciary whose decisions are enforced, governments that function adequately, and diverse and independent media. These nations have only limited problems in democratic functioning…

“By contrast, flawed democracies [like the U.S. #25] are nations where elections are fair and free and basic civil liberties are honoured but may have issues (e.g. media freedom infringement and minor suppression of political opposition and critics). These nations have significant faults in other democratic aspects, including underdeveloped political culture, low levels of participation in politics, and issues in the functioning of governance.”[2]

It would seem that Americans today have much to learn about democratic and republican governance, especially from the highest-ranking countries like Norway (#1) and New Zealand (#4), but also from Latin American countries like Uruguay (#15), Chile (#17), and Costa Rica (#18).

The mixture of truth and myth in the American Dream is an example of ideology. This term refers to the political worldview of a social group—whether a nation, social movement, political party, religion, or socio-economic class. Historian Thomas Holt (1992) defines ideology as “a particular systematic conjuncture of ideas, assumptions, and sentiments…” (25). Ideologies are abstract and often inspiring worldviews, reflective of individuals’ material self-interest as well as non-material ideals and values (Whimster 2007). Like any other political community (polity), the U.S. has always promoted certain ideologies about itself, and favored or opposed those of other polities relevant to itself. It is a basic historical and sociological observation that all nations (e.g., China, the United States, Norway) and all political parties (e.g., Republicans, Democrats, Greens) have ideologies. However, for members of those nations or parties, it may be difficult to understand how “their” worldview could be anything but the Truth, especially when contact with other perspectives is limited.

In addition to the American Dream, characteristic of U.S. domestic policy, a longstanding ideology of U.S. foreign policy asserts that the nation has usually been a force for good in the world, a “beacon of freedom.” This worldview, with roots in the colonial period, is called American Exceptionalism (Madsen 1998). A comparative, international perspective would observe that—although American power and example have often supported liberty abroad—it is also true that America has frequently sought to repress freedom in other nations. Supporting this point is the long history of U.S. interventionism in sovereign Latin American nations (see Chapter 12).

Political (dis)satisfaction is one factor social scientists use to measure a nation’s strength of democracy. Growing political frustration is characteristic of weakening democracy. According to many scientific surveys, Americans have become increasingly dissatisfied with various aspects of government, a trend starting in the later 1960s in the context of the black-led Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War. Following the 1960s-1970s, the U.S. political center began shifting to the right during the Reagan-Bush administrations (1980-1992), with Democratic presidents Clinton and Obama staking out centrist rather than traditionally leftist economic and social positions (APAN:II:Ch.29; Carter 1995; Klinkner & Smith 1999:Ch.9). Intense popular dissatisfaction with political process and performance has accompanied the political polarization between the new right and new left. Such dissatisfaction exemplifies important social criticisms voiced across the political spectrum. Today, Americans of all political stripes offer criticisms of how values and ideals are (or are not) reflected in society and government—especially at the federal level (executive, legislative, and judicial branches) but also at state and local levels.

Likewise, in this textbook you will encounter evidence-based criticism of the United States, as we discuss diversity. Criticism of particular policies and views is distinct from underlying commitment to the nation. The most useful criticism not only identifies social problems and injustices, but also proposes detailed actions for fixing or reforming them. There are important reasons for this kind of national self-reflection; perhaps the biggest is the urgent need to strengthen American democracy. Regarding diversity, there are many ways the nation today fails to live up to its values of equality and fairness.

History shows many eras of reform of American institutions. For instance, slavery was a popular, venerated, and widely defended American institution. It took a small group of patriotic citizens (abolitionists like Douglass) to condemn it as violating national and human values. Likewise, the Progressive Era (1900-1920) featured much social criticism in the name of justice and progress. We can all agree that some positions taken by public officials representing the American people were wrong in the historical past. Likewise, today the U.S. may in some aspects of its domestic and foreign policies be in the wrong. Today, there is much need for reform, with many Americans strongly dissatisfied with politics and governance, criminal justice and policing, environmental inaction, educational mediocrity, etc. We must squarely admit to our social problems if we are to improve our nation’s ability to solve them. This is the time-honored and democratic role of social criticism in our republic.

In sum, social criticism plays a role of overriding importance in open societies. Democracy requires citizens’ ability to take a critical view of the gap between values (ideals) and social reality, the difference between words and actions. If we believe in such values, it is not somehow “unpatriotic” to criticize America for failing to live up to them.

Figure 2.1.[3] Dissent and controversy are essential features of open societies with modern forms of government. Like many countries today (such as Bangladesh in the photo), the U.S. is officially a republic (sovereignty inheres in the people). This is identical to saying the U.S. is a democracy (the people rule).

2.3 Repression and Social Criticism in Action

Despite the importance of dissent, all democracies have experienced repression and conformity. A major example of twentieth-century repression (McCarthyism) appears below. Then we discuss an example of nineteenth-century dissent—Douglass’ attack on slavery.

The first example is extreme anticommunism during the 1950s. Fears during the early Cold War (1945-1991) led to political conformity and repression of dissent. Important civil liberties were stifled in the supposed interest of national security (APAN:II:753, 772). Extreme anticommunism in the early Cold War (aka McCarthyism) found champions in Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) (ibid:755). In hindsight, many Americans and foreign observers have seen McCarthyism as harmful to basic values of open, democratic societies.

The second example—here of social criticism and dissent—is Frederick Douglass’ 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” The context of Douglass’ early career (1840s-50s) was strict intolerance in the South of abolitionist or any other criticism of slavery. This trend of increasing southern hostility to public debate and restriction of abolitionist views in print dated to the aftermath of the 1820 Missouri Compromise and the 1822 Denmark Vesey conspiracy in Charleston, South Carolina (Levine 2005:166). Likewise, the North experienced a good deal of suppression of slavery criticism (ibid:167-68; Klinkner & Smith 1999:39-40).

Douglass delivered “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” to a white, abolitionist audience in Rochester, New York on Independence Day, 1852. It has been described as among the greatest works of American literature on the meaning of freedom in a republic (Douglass 2017:174). Many readers have concluded it was indeed vital for Douglass’ searing accusation of America to be heard, and that attempts to suppress it in the name of patriotism or economic interest were wrong.

“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”[4]

“This…is the 4th of July. It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom…Fellow-citizens, I shall not presume to dwell at length on the associations that cluster about this day. The simple story of it is that, 76 years ago [1776], the people of this country were British subjects. The style and title of your ‘sovereign people’ (in which you now glory) was not then born. You were under the British Crown…

“But, your fathers, who had not adopted the fashionable idea of this day, of the infallibility of government, and the absolute character of its acts, presumed to differ from the home government in respect to the wisdom and the justice of some of those burdens and restraints. They went so far in their excitement as to pronounce the measures of government unjust, unreasonable, and oppressive, and altogether such as ought not to be quietly submitted to…To say now that America was right, and England wrong, is exceedingly easy…It is fashionable to do so; but there was a time when to pronounce against England, and in favor of the cause of the colonies, tried men’s souls. They who did so were accounted in their day, plotters of mischief, agitators and rebels, dangerous men. To side with the right, against the wrong, with the weak against the strong, and with the oppressed against the oppressor! here lies the merit, and the one which, of all others, seems unfashionable in our day. The cause of liberty may be stabbed by the men who glory in the deeds of your fathers…

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent [African Americans, enslaved or free], to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us? Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions!…I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale [bounds, fence] of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes [whippings, lashes] and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine…

“…My subject, then fellow-citizens, is AMERICAN SLAVERY. I shall see, this day [July 4th], and its popular characteristics, from the slave’s point of view. Standing, there, identified with the American bondman [slave], making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker [more evil] to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery—the great sin and shame of America!…

“Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery…I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope…”

2.4 “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”: Discussion of Douglass’ Speech

Douglass’ nineteenth-century polemic against racialized slavery dealt with an institution that no longer exists in America. Yet it’s important to understand crucial connections between his attack and social criticism today. Although U.S. chattel slavery is a thing of the past, racial injustice—albeit in less extreme forms—is not. Notice four features of Douglass’ speech:

(1) Douglass uses pronouns in important ways: for example, “you” (white, free) versus “me” (black, unfree). How does this pronoun usage relate to the speech’s title?

(2) Notice Douglass’ observations about exclusion and racial “disparity.” He, like other African Americans—enslaved or nominally free—is “not included” in the freedom celebrated by his white audience on Independence Day. Northern and Southern free blacks faced severe legal and extralegal limitations of their civil and political rights. How did antebellum U.S. society include some kinds of people (e.g., white men) and exclude other types (e.g., white women, people of color) from political and civil society?

(3) Douglass insists on discussing America “from the slave’s point of view.” How is this empathy and compassion analogous to seeing America in more recent times from the point of view of vulnerable and powerless people, members of marginalized social groups? How does this view from below—the perspective(s) of the conquered (León-Portilla 1972)—contribute to our understanding of American diversity? (Refer back to the Chapter 1 opening poem: “America the beautiful, / Who are you beautiful for?”)

(4) Finally, notice that Douglass, after attacking America in 1852, ends by affirming “hope”: that the situation, no matter how unjust, can yet be remedied and justice triumph. This feature, rooted in Douglass’ Christian faith, also characterized Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1950s-60s speeches (Morris 1986). What can we learn today from this affirmation of hope, about criticism proposing social change? How does Douglass illustrate the earlier points about social criticism in the service of national, and human, values?

Chapter 2 Summary

Chapter 2 introduced social criticism and its relationship to diversity learning. Section 2.1 discussed reflexivity, a concept referring to how our social identities influence our experiences. Our social criticism (or lack of it) will reflect our positions and identities in society.

Section 2.2 described the role of social criticism in holding society accountable to its claimed values. Social criticism refers to critical reflection on the gaps between a community’s values and ideals, and its actual practices. It explained how the U.S. currently falls short in international, social scientific measures of democracy. Ideology was defined as the political worldview of a particular community, party, or nation. All communities and nations promote certain ideologies about themselves, including the U.S.

Section 2.3 presented two examples relevant to repression of dissent and social criticism. First, early 1950s McCarthyism exemplifies how extreme anticommunism threatened American democracy. Second, Frederick Douglass’ 1800s abolitionism illustrates how social criticism can serve democracy and other political values such as fairness and equality.

Section 2.4 discusses Douglass’ 1852 speech—“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”—suggesting its great relevance to social criticism today.

[1] Image: Public domain

[2] Source: Wikipedia, “Democracy index.” 2020 rankings. Accessed 6/13/21.

[3] Image credit: Creative Commons license (“Bangladeshi Spectrum workers protest deaths” by dblackadder is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

[4] Source: https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/coretexts/_files/resources/texts/c/1852%20Douglass%20July%204.pdf

See also Douglass 2017:148-68.