Ellis Island in New York Harbor (left image) illustrates nineteenth- and early twentieth-century mass immigration to the United States, and nativist reactions.[1] From 1892 to 1954, about 15 million immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were processed here for U.S. entry (APAN:II:494). They were mostly poor, non-English-speaking, and perceived by American authorities as not fully white. The dominant vision of America was as a “melting pot,” in which Americanization of immigrants required complete assimilation into white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) culture. Despite nativist efforts, this vision never entirely reflected reality.

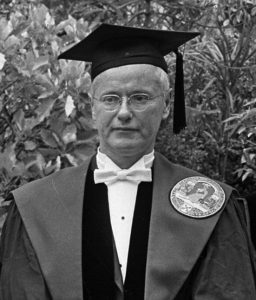

At Columbia University—not far from Ellis Island—Robert King Merton (right image; see Chapter 1) was developing new functionalist ideas in the 1940s that would soon make him a famous sociologist.[2] As an ambitious young man, he had invented this name because it sounded “American.” He knew that adopting WASP culture would help him get ahead in American society. His birth name was Meyer Robert Schkolnick. Born in Philadelphia in 1910, he was a second-generation Russian Jew whose Yiddish-speaking family had immigrated in 1904. His father, Aaron Schkolnickoff, had himself received an “Americanized” name at port of entry: Harrie Skolnick.[3]

How does Merton’s story illustrate both European immigration, and nativist pressures on immigrants? What similarities exist between nativism in the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries? Why do today’s descendants of immigrants, who suffered discrimination and exclusion at the hands of WASPs, now repeat this exclusion of new immigrants?

Chapter 6 Learning Objectives

6.1 Who are “Real Americans”?

- Explain why people immigrate

- Define nativism

- Understand how WASPs became a cohesive racial-ethnic group in early U.S. history

6.2 Immigration and Expansion to 1860: Ireland, Germany, Mexico

- Understand why WASPs saw Irish Catholics as nonwhite

- Recognize examples of nativist violence toward Irish and Germans

- Describe how U.S. expansion created the Mexican border and Southwest

6.3 The New Immigrants, 1860-1929: Europe, Mexico, East Asia

- Understand how sending regions shifted to southern and eastern Europe

- Identify which U.S. regions received East Asian and Mexican immigrants

6.4 The New Nativism

- Understand the significance of 1920s immigration quota laws

- Recognize differences between haphazard exclusion of European immigrants and systematic exclusion of East Asians, Mexicans, and African Americans

- Define the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

Chapter 6 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

melting pot: a metaphor of Americanization used between 1880-1920. It pictured immigrants as needing to be completely assimilated into white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) culture.

nativism: organized political opposition to immigration. Arises from fears of the native-born that immigrants are worsening the nation or local community

WASP: white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Pre-1945 American Protestants of northern or western European ancestry

Protestantism: the branch of Christianity arising in the 1500s European religious reform movement that split from Roman Catholic Christianity

manifest destiny: in the 1800s, a collection of white-supremacist ideas claiming God’s intention that U.S. whites expand across the North American continent “from sea to shining sea.” Some versions called for U.S. expansion throughout the Americas.

proletariat: the economic class of people owning little beyond the sheer ability to labor

Know Nothing Party: an 1850s third party embracing nativism and nationalism. Aka the American Party.

the Mexican Cession: the vast region of northern Mexico that became American following Texas independence (1836) and the U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846). To “cede” (cession) is to relinquish (to give up land or control). Mexican inhabitants became U.S. federal citizens under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848).

Chinese Exclusion Act: 1882 federal law suspending immigration and naturalization of Chinese, mostly manual laborers. An example of anti-Asian immigration policies (versions of white nationalism) in effect until 1965.

WWII Japanese American internment camps: The U.S. Army’s forcible removal from their homes and prolonged detention of virtually all Americans of Japanese ancestry, from 1942 to 1946.

6.1 Who are “Real Americans”?

Immigration and migration are universal features of the human experience in world history. People have always left their homelands: whether as entire peoples, in smaller groups of clans or families, or individually. Perhaps the most common reasons have been: (1) insecurity (violence or persecution, natural disasters such as famine or disease), as when co-religionists fled religious persecution; and (2) limited opportunity (social structural constraints on life chances), as when younger sons left home seeking their fortune, because eldest sons inherited all (primogeniture).

Today, throughout the world, tens of millions of people abandon their homes and illegally cross international borders each year. The main causes are the perennial ones of insecurity and limited opportunity in their homelands (Nazario 2007). Sociologists of immigration often explain these facts in terms of “push” and “pull” factors (Schaefer 2015:84). Factors like lack of work or violence exert a “pushing” force in a region, leading some people to leave in search of work or safety. Likewise, factors such as presence of work or relative safety exert a “pulling” force in other regions, attracting people from elsewhere. Sociologists also distinguish between “migration”—moving in seasonal patterns from home to work—and “immigration”—moving with the intention to stay. Finally, sociologists describe some regions as “sending” countries and others as “receiving” countries. Generally, the global South tends to “send” and the global North “receive.” Today many migrants and immigrants to Europe and North America come from “Third World” regions such as the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.

Immigration often creates political opposition: nativism. As in many past eras, a major political controversy of our own time pits nativists against immigrant advocates. Nativism means opposition to immigration—by foreigners or domestic outsiders—and emphasis on the virtues of the native-born or local. Alternately, it may advocate limited (“sensible”) immigration but with emphasis on complete assimilation. This stance has played a perennial political role in human society as such, influencing perceptions and actions in all likelihood for tens of thousands of years.

Nativism arises from fears of the native-born that immigrants are worsening the nation or local community. Thus, nativism feeds on xenophobia (literally, “fear of outsiders”) and resistance to change. Such fears are economic (“they’re stealing our jobs” or “lowering our housing values”), political (“they’re voting the wrong way”), or social (“they’re increasing poverty and crime” or “they’re marrying our children”). These sentiments are typically voiced politically not as fears or anxieties but as strident nationalism (or localism) proclaiming one’s nation (or local community) to be the “best” or the “greatest,” and tapping nostalgia for a lost past perceived as simpler and better. In the 1830s, nativists perceived the 1790s as a golden age; today, this perception fixates on the 1950s. Rhetoric dehumanizes immigrants as a “tidal wave” “swamping” and “invading” (Bonilla-Silva 2018:xiv). Although immigration, at some times and places, may indeed worsen existing social problems (Nazario 2007), nativist solutions are often too simple to be effective.

White, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. In American history, nativism in some form has influenced all periods of colonial and national life. Since it relies on a strong distinction between the native-born (“us”) and the foreign-born (“them”), there must be not only a significant “them” to deplore, but also a cohesive “us.” As functionalist sociologist Emile Durkheim observed (see Chapter 1), opposition to the out-group creates and renews solidarity of the in-group (Emirbayer 2003).

In the nineteenth century, the most powerful and numerous American racial-ethnic group—the native-born “us”—was white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. “WASP” refers to pre-1945 American Protestants of northern or western European ancestry. Political, economic, and social power all centered in this group. Members included British-born colonists such as John Smith and John Winthrop; American-born (Creole) revolutionists such as George Washington and John Adams; nineteenth-century politicians such as John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln; later nineteenth-century industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller; early twentieth-century politicians such as Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt and entrepreneurs such as Thomas Edison and Henry Ford. After WWII, WASPs increasingly accepted white ethnics as fully “white” and “American,” and in the process lost much of their former group distinctiveness and identity. Nevertheless, it is revealing that, prior to 2020, all U.S. presidents (except Kennedy and Obama)[4] and most high-level politicians remained WASP. The U.S. has never had a president of southern (Italian) or eastern (Slavic, Jewish) European ancestry. Likewise, although virtually all pre-1965 southern lynching victims were African Americans, a few were Italians.

Figure 6.1.[5] Many 1800s farm families were white, of northwestern European ethnicity, and Protestant Christian (WASP).

WASP identity comprised distinctive racial (white), ethnic (Anglo-Saxon), and religious (Protestant) features. Protestantism arose in the Reformation, the sixteenth-century reform movement that split from Roman Catholic Christianity (Bataillon 2013). By the 1800s, it had further splintered into many sects: Lutheran, Episcopalian, Baptist, Presbyterian, Quaker, Congregationalist, Methodist, African Methodist Episcopal, and more. However, the Protestant world was generally united in hostility toward Catholics, and belief in an ideology of “progress” in which Protestantism was gradually replacing non-Christian religions and Catholicism throughout the world. Accordingly, American Protestantism was closely linked to American exceptionalism and imperialism, and thereby to whiteness and white supremacy. Manifest destiny, a collection of ideas claiming God’s intention that white Americans expand across North America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, was key here (see Chapter 12).

The WASP group was internally diverse, reflecting religious sectarian variety and comprising several European-American ethnicities: English, Scottish, Scots-Irish (Protestant Northern Ireland), Welsh, Protestant Germans, and more (APAN:I:97). The European groups had developed strong political cohesion especially after 1763, when decaying loyalty to the British empire led to American independence (1783). Likewise, they claimed fundamental differences between themselves and African Americans (slave or free), on the one hand, and Native Americans, on the other. References to the American “People” in political speech and documents of the early republic (e.g., 1787 Constitution Preamble) denoted WASPs—with Catholics, Indians, and Negroes excluded. In the nineteenth century, white supremacy and the view of (white) Americans as a chosen people formed the commonsensical social outlook of most whites (Klinkner & Smith 1999:40). By the 1830s-40s, large-scale European immigration, combined with geographical expansion into Mexican territories (Weber 1982), would challenge this exclusive, narrow sense of American racial-ethnic and religious identity.

So, who are the “real Americans”? History suggests that yesterday’s immigrants, suffering discrimination and exclusion at the hands of yesterday’s native-born, may become today’s (or tomorrow’s) nativists advocating exclusion of today’s immigrants (Blumer 1958). Understanding this cycle can develop one’s consciousness of history’s patterns, and self-awareness (see Chapter 2 on reflexivity). Vulnerable people today include both immigrants and natives harmed by immigration (Nazario 2007).

6.2 Immigration and Expansion to 1860: Ireland, Germany, Mexico

The nineteenth century was a time of large-scale European immigration, especially to northern cities, sparking nativist reaction. It was also a century of westward expansion, with the U.S. invading northern Mexico to create the new Southwest.

The first era of mass immigration in U.S. history started in the 1830s and lasted to the eve of the Civil War (1861-1865). In these years, the number of new immigrants—almost 5 million—was greater than the nation’s entire 1790 population (APAN:I:293-94; Levine 2005:59). The new Americans came almost entirely from northwestern Europe, principally Ireland, Germany, and England. This inflow was larger than any previous, visibly changing the face of many northern cities. “By 1852-53, Boston and New York…had 50% foreign-born population…Close to that in Philadelphia. The Northern cities—seats of market culture, commercialism, manufacturing—were immigrant cities” (Blight 2008, Lecture 4, 31:03). In 1855, 28% of New Yorkers had been born in Ireland, 16% in the German principalities. 1850s Boston’s population was approximately 35% foreign-born, with most of this group (over 66%) being Irish (APAN:I:294). By 1860, the foreign-born comprised over 40% of the population of New York, Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and San Francisco (Levine 2005:59).

Immigrants differed from prior ones in ways that WASPs perceived as crucial: many were Catholic, poor, unskilled, and resistant to adopting Protestant culture. Many swelled the ranks of the urban poor, contributing to northern cities’ growing proletariat (those owning little beyond the sheer ability to labor: Tucker 1978). A few were exiled socialists from failed European revolutions in 1848. Overall, they seemed to lack the virtues WASPs saw in themselves.

Irish Americans appeared particularly threatening, given their determination to maintain old-country institutions such as Catholic religiosity and education, and customs such as social drinking. They had many reasons to mistrust American WASPs. Ireland had been an English colony since the later sixteenth century; the first English overseas plantations were not in Virginia or Barbados, but in Ireland (Fredrickson 1981:13-17). The 1800s Catholic population remained firmly under Protestant British control. London’s mishandling of Irish events in the 1830s-40s significantly contributed to the devastating Potato Famine of 1845-52, in which one million Irish died of starvation or disease and over one million emigrated.[6] Irish Americans thus tended to perceive WASP nativist pressures to assimilate as more of the same Protestant oppression they had endured back home. WASPs, in turn, described Irish as lazy, dirty, stupid, and savage, frequently comparing them to African Americans, the so-called “smoked Irish” (Holt 1992; Ignatiev 2009).

Table 6.1. Major immigration events to 1860

| Date | Event | Description |

| 1798 | U.S. law on illegal immigrants and sedition | During anti-French XYZ Affair, law prohibits entrance of “illegal immigrants” endangering national peace and security, and provides for their expulsion. It also threatens civil liberties of U.S. citizens. |

| 1830s-40s | Anti-Catholic riots in Northeast | Catholic, German, Irish immigrants attacked. |

| 1846 | Invasion of Mexico | In an atmosphere of aggression stoked by President Polk, U.S. General Taylor provokes war with Mexico. The Mexican War (1846-1848) ends with occupation of Mexico City under General Winfield Scott. |

| 1848 | Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo | Mexican citizens become U.S. federal citizens in the new Southwest territories. Treaty guarantees protection of their land ownership, but in coming years is repeatedly violated by immigrating WASPs, especially in New Mexico. |

| 1853 | Creation of Mexico-U.S. border | Mexico’s territorial losses to U.S. (1848, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; 1853, Gadsden Purchase of La Mesilla) are half of its claimed territory (including Texas). The resulting international border is 1,954 miles long (3145 km). |

| 1848-60 | Peak period of pre-Civil War immigration | Nearly 3.5 million immigrants enter U.S., including 1.3 million Irish and 1.1 million Germans. Proportionate to population, this is the largest inflow of foreigners ever in American history |

| 1850s | Ongoing nativism in national politics | The anti-immigrant and nationalist “American Party” (aka “Know Nothing Party”) forms. |

| 1860 | Larger northern cities are “immigrant cities” | 15% of the U.S. white population is foreign born. 90% of immigrants live in the North. |

Sources: Adapted from APAN:I:293-94, 366; Cisneros 2002; Weber 1982

As immigration accelerated between 1830 and 1860, WASP nativism intensified. Although Germans had been arriving since the eighteenth century, especially to Pennsylvania, the larger scale of immigration, growing temperance (anti-alcohol) sentiment, and ongoing anti-Catholicism sparked nativist riots targeting both Germans and Irish (APAN:I:294). In addition to religious intolerance, there were economic and social fears, with native-born laborers attracted to nativist politics scapegoating immigrants for job scarcity and low pay (ibid). By 1850, many WASPs of all political stripes were eager to blame immigrants for the nation’s troubles (Levine 2005:200-01). This nativist base supported the anti-immigrant “American Party” (aka “Know Nothing Party”). The party itself was short-lived—its members absorbed by the new Republican Party in the mid-1850s (APAN:I:366)—but intense nativist sentiment continued into the Civil War years and beyond.

Additional challenges before 1860 to WASP notions of American identity came from expansion into northern Mexico. Westward migration stemmed from economic motives, but also from white-supremacist manifest destiny: the idea that God intended racially superior U.S. whites to have the land and resources of North America (Klinkner & Smith 1999:40; see Chapter 12). After the 1846-48 Mexican War and 1853 Gadsden Purchase, the U.S. possessed the Mexican Cession—a vast western region with centuries of European (Spanish) colonization since the 1500s. Long before 1846, Spain had given European names and political identities to the new U.S. states or territories (e.g., California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas), towns or forts (e.g., San Francisco, Monterey, Los Angeles, San Diego, Tucson, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Las Cruces, El Paso del Norte, San Antonio, Laredo), and geography (e.g., San Francisco Bay, Monterey Bay, El Mar de Cortez or Gulf of California, Colorado River, El Río Bravo or Rio Grande). Present-day controversies over the relationship between U.S. globalism and Hispanic immigration originate in these mid-nineteenth century events (see Chapter 13).

6.3 The New Immigrants, 1860-1929: Europe, Mexico, East Asia

After the Civil War and especially by 1880, immigrant-sending regions had shifted to southern and eastern Europe. Significant immigration also came from Mexico and East Asia (China, Japan).

Immigration, paused by the Civil War, quickly resumed its torrential flow to the North and West after the South’s surrender at Appomattox. Overall, U.S. immigrants between 1870 and 1920 formed part of a global migration exodus from Europe and Asia caused by increased population, industrialization, redistribution of land, and religious intolerance. In these decades, millions of individuals and families immigrated to Argentina, Brazil, Australia, Canada and the United States (APAN:II:492). In the ten years alone after the U.S. Civil War, almost 3 million immigrants flocked to northern and western industrializing cities (APAN:I:439).

Thus, some pre-1860 patterns continued: mass European immigration, especially to northern cities. However, by 1880 the new sending regions—Italy, Austria-Hungary, Greece, Poland, Russia—were increasingly alien to WASPs. According to contemporary racial ideas, WASPs were “Anglo-Saxon” or “Teutonic”; they saw themselves as racially distinct from and superior not only to Irish Celts, but also to southern Italians and Sicilians and eastern Slavs and Jews (Gould 1996). Although contemporaries often spoke of the “white” (or “Caucasian” or “American”) race, they also saw many hierarchical gradations of whiteness. Not all were equally white: some were of “pure white” race, whereas “off white” white ethnics were not.

The new European Americans added to previous Catholic challenges to WASP notions of American identity. Appearing now were not only more Roman Catholic Christians but also sizable communities of Eastern Orthodox Christians and Jews (Brodkin 1998). Overall, 26 million immigrants arrived between 1870 and 1920, with most staying to settle in cities. For instance, Catholic Italians mostly immigrated between 1900 and 1915 (Telles & Ortiz 2008:10). Immigrants contributed to redefining and changing American society and culture, often in ways that longer-settled Americans feared and deplored (APAN:II:492). For the near-century between 1830 and 1920, northern and western towns were immigrant cities; between 1877 and 1920, in many cities immigrants were more numerous than the native-born (APAN:II:503). Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century industry relied on the newcomers’ labor and consumption, making possible America’s rise as a world economic power.

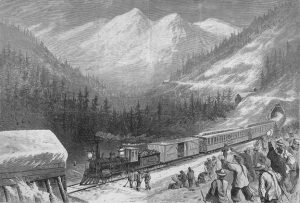

East Asian and Mexican immigration had also greatly increased in the second half of the 1800s. Chinese newcomers to the West rubbed shoulders with WASPs, together completing the first intercontinental railroad in 1869. “Chinatowns”—Chinese American enclaves or ghettos—appeared in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and elsewhere, where many Chinese operated laundries (Riis 1890). Other groups in Western towns were WASPs, Native Americans, African Americans, and Mexican Americans. The latter group included those who pre-dated 1848, especially in New Mexico (“We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us”: Gómez 2018:2). Mexicans panned for gold in Northern California, performed southwestern agricultural and domestic labor, and added to booming towns like Los Angeles and San Francisco. By 1910, Mexican immigrants outnumbered Irish newcomers (APAN:II:492).

Figure 6.2.[7] Many Chinese immigrants to the West worked building railroads in the later 1800s. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred further Chinese immigration (Gómez 2018:145).

Unlike East Asia or Europe, Mexico was not separated from the U.S. by vast oceans, but only by an invisible international border almost 2,000 miles long. Mexico-U.S. government border presence did not arrive until the early twentieth century, gradually transforming into the intense border militarization of recent decades. Moreover, much of the Southwest and West had been Mexican territory prior to 1853, and Spanish before 1821. Accordingly, the Hispanic world didn’t first come to the U.S.; rather the U.S. came to the Hispanic world (Fuentes 1992:444-45). In many ways, then, immigrant and migrant Mexicans (unlike Europeans and Asians) were not entering an alien continent or country, but rather returning to an ancestral homeland increasingly populated by unfriendly WASP newcomers. Indeed, many Mexicans—as in New Mexico and California—had never left.

Table 6.2. Major immigration events, 1860-1929

| Date | Event | Description |

| 1860-70 | Violence against Chinese, Irish, Mexicans. Anti-Mexican land fraud | The majority of U.S. citizens of Mexico origin (in Southwest) see their land taken and civil rights ignored. Some are lynched. Such actions violate the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. |

| 1882 | Chinese Exclusion Act | U.S. law suspends immigration and naturalization of Chinese, who are mostly manual laborers. Mexican immigration is increasing. |

| 1891 | Immigration control law | U.S. Immigration Law. The first exhaustive U.S. law attempting national control of immigration. |

| 1900-33 | Mass immigration from Mexico to Southwest and West | About 1/8 of the entire Mexican population moves to U.S. territory. Primarily due to the violence and economic uncertainty of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). America is the major arms supplier to the various Mexican armies. |

| 1907 | Japanese ban | U.S. economic depression. President T. Roosevelt’s Gentleman’s Agreement pact prohibits entry of Japanese workers. |

| 1907-08 | Overall immigration hits peak | Great influx of southern and eastern Europeans

|

| 1909 | Importation of Mexican labor | U.S.-Mexico pact brings Mexican workers to California for agricultural labor. |

| 1917 | Importation of Mexican labor | U.S. again imports Mexican workers, facing labor scarcity due to U.S. entrance in WWI. |

| 1917 | Immigration law | Restricts Asian entry. Introduces literacy tests and a tax of 8 dollars per head for entrance. Such practices block legal entry of the nonwhite poor and uneducated. Anti-German nativism and laws during and after WWI. |

| 1921 | Emergency Quota Act | Establishes yearly immigration quotas for each nationality, privileging Anglo-Saxon Protestants and restricting Catholics and Jews. |

| 1924 | Immigration Act (includes Asian Exclusion Act, and National Origins Act) | National Origins Act replaces the 1921 Quota Act. Limits annual immigration to 150,000 people and sets quotas at 2 percent of each nationality residing in the United States in 1890, except for Asians, who are banned completely. (Chinese had been excluded by legislation in 1882.) Further restricts southern and eastern Europeans.

Establishes U.S. Border Patrol (la Patrulla Fronteriza, la migra) and deportation of those who become a public burden, violate U.S. laws, or participate in anarchist and seditious acts. |

| 1927 | National Origins Act is revised | Apportions new quotas to begin in 1929. Retains the annual limit of 150,000 but redefines quotas to be distributed among European countries in proportion to the ‘national-origins’ (country of birth of descent) of American inhabitants in 1920. Entrants from Western Hemisphere (Canada, Mexico) don’t fall under the quotas (except for those whom the Labor Department defined as potential paupers), and soon they become the largest immigrant groups. |

| 1929 | Penalty for undocumented re-entry | Penalizes undocumented re-entry for previously deported illegal immigrants. Meanwhile, the quota system guarantees that most U.S. immigrants are white (from northwestern Europe or Canada). |

Sources: Adapted from APAN:II:618, 635-36; Cisneros 2002; Wright & Rogers 2011

6.4 The New Nativism

The new Americans (1880-1920) all experienced hostility from WASPs and older immigrants, but of different kinds. Whereas new European Americans suffered haphazardly, Mexican Americans and Asian Americans experienced total and systematic exclusion akin to antiblack oppression.

With roots in pre-1860 nativism, newer advocates of white American racial purity reacted with alarm to the new European immigration. They were part of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century global resurgence of white supremacy fueled by immigration fears, eugenicist pseudo-science, and white imperialism targeting Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific (Ferrer 1999; Kevles 1995). Accordingly, some Progressive-Era (1895-1920) reformers advocated immigration restriction as a means of advancing eugenicist goals of “improving” the racial quality of society (APAN:II:547). They joined forces with many other WASPs, demanding legislation that would block further immigration by eastern and southern Europeans, and by Asians. In the 1920s, these nativist efforts succeeded in ending the post-1880 period of mass immigration. Indeed, 1920s quota laws, combined with reduced flow from sending countries, ended the near century (1830-1920) of mass European immigration. The percentage of foreign-born Americans fell dramatically in subsequent decades, not rising again until the late twentieth century after 1965 (ibid:886). Subsequent decades (1930s-1960s) saw gradual assimilation of white ethnics into WASP society (see Chapter 7), as well as ongoing importation of Mexican agricultural labor to the West and Southwest.

Despite white inter-ethnic tensions, European newcomers experienced exclusion in relatively mild and unsystematic forms. By contrast, systematic and legalized exclusion of Mexicans and East Asians was comparable to treatment of blacks. Variation in WASP racism (1880-1920) created the contrasting residential patterns contributing to mid-century acceptance of white ethnics as socially “white,” and mid-century ongoing exclusion of Mexicans, East Asians, and African Americans (Fernandez 2012; Takaki 1989). Residential segregation limited these latter groups’ opportunities for economic advance and social integration (Cf. Telles & Ortiz 2008:42). Whereas white ethnics (1930-1965) increasingly crossed the color line, achieving political power and urban and suburban integration in housing and schools, Mexicans and East Asians (like African Americans) endured continuing political exclusion and racial segregation (APAN:II:494; Klinkner & Smith 1999:326). White exclusion created similarly monoethnic ghettos of Chinese (e.g., San Francisco’s Chinatown) and Mexicans (e.g., East Los Angeles). Residential and school segregation limited their opportunities for advance, whereas multiethnic integration of Europeans allowed such advance (APAN:II:495).

Today’s descendants of white ethnics tend to overlook this history. Many of their immigrant ancestors worked very hard to rise in American society. However, they did so on a playing field that was far from level: discrimination against African Americans, East Asians, and Mexicans was far more severe, creating patterns of exclusion lasting into the present (Massey & Denton 1993:2; Sanchez 1993).

Anti-Asian nativism. Anti-Asian politics was based in WASP hostility toward Chinese and Japanese. Immigration law, for example, was particularly discriminatory against East Asians, maintaining exclusion until the 1965 Immigration Act ended nationality quotas favoring northwestern Europeans. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act had suspended immigration and naturalization of Chinese, mostly manual laborers. But immigration policy formed only part of a much wider spectrum of WASP anti-Asian actions, including violence and terrorism, housing and school segregation, and property disqualification (APAN:II:571). WASPs also excluded Asians from opportunities in civil society, such as male intermarriage with white women (also denied to African Americans) (ibid:462-63).

Early 1900s anti-Asian exclusion culminated in WWII Japanese American internment camps (originally called “concentration camps”: Klinkner & Smith 1999:179). Responding to President Roosevelt’s go-ahead in February 1942, the Army began removing virtually all Americans of Japanese descent from their homes; many internments lasted until 1946 (APAN:II:701). Army justifications, based in white supremacy, claimed that the “Japanese race is an enemy race,” that “racial affinities are not severed by migration” from Japan to the U.S., and that even among “third generation Japanese born in the United States, [the] racial strains are undiluted” (quoted in Klinkner & Smith 1999:179).

Further evidence likewise suggests that Japanese internment primarily stemmed from anti-Asian racism rather than sheer wartime necessity: (1) The Army dealt with German Americans and Italian Americans as possible security threats on an individual basis. By contrast, Japanese Americans were judged collectively, en masse. (2) The British handled all possible internal security risks on an individual basis, regardless of race or nationality. (3) The Army failed to find any Japanese Americans guilty of active subversion (ibid:194). In 1988 the U.S. government officially apologized and offered financial reparation ($20,000) to each surviving internee, of whom about 60,000 were still living (APAN:II:701). However, this response paled in comparison to victims’ lost dignity, homes, and jobs during the war, and decades of continued post-1945 exclusion (Harvey 2007:227).

China—in contrast to Japan, Germany, and Italy—was a U.S. wartime ally. In 1943, Congress accepted Chinese immigration on a largely symbolic rather than actual basis. It ended the Chinese Exclusion Acts, made naturalization possible for people of Chinese ancestry, and assigned a yearly immigration maximum quota of 105 people from China (Klinkner & Smith 1999:377). In the Army, Chinese Americans (like Hispanics and Native Americans) served in white units, whereas African Americans and Japanese Americans served in racially segregated units (APAN:II:705). As noted, Congress did not eliminate white-supremacist immigration quotas until 1965 (see Chapter 13). However, the 1960s also saw the dramatic escalation of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. Though officially fought with Asian allies, the Vietnam War was a conflict against an Asian enemy, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. As with anti-Japanese racism during WWII, so during this war many Americans learned to see the Vietnamese as racial and social inferiors (Klinkner & Smith 1999:286). As with African Americans and Mexican Americans, white anti-Asian racism and nativism has had a long history in America.

Chapter 6 Summary

Chapter 6 presented the history of early immigration to the United States, and nativism. Section 6.1 explained why people immigrate in terms of two factors: insecurity and limited opportunity. It defined nativism as fear of the native-born that immigrants are worsening the nation or local community. The section also explained how WASPs became a cohesive racial-ethnic group.

Section 6.2 presented the history of immigration to 1860, the eve of the Civil War. WASPs saw the major immigrant groups, especially Irish Catholics, as nonwhite and reacted with nativist violence. The section also described how U.S. westward expansion created the Mexican border and Southwest.

Section 6.3 continued the story of mass immigration, from 1860 to 1929. Immigrant sending regions shifted to southern and eastern Europe, as well as East Asia and Mexico. Europeans came especially to northern and eastern urban areas, whereas East Asians and Mexicans arrived mostly to western and southwestern areas (both urban and rural).

Section 6.4 discussed the development of nativism after 1860. Renewed racism and nativism led to the end of mass immigration in the 1920s, when immigration quota laws were introduced. Variation in WASP racism involved only haphazard exclusion of European immigrants, but systematic exclusion of East Asians, Mexicans, and African Americans. An example is the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

[1] Image: Public domain

[2] Image credit: Creative Commons license (Eric Koch / Anefo – Nationaal Archief 917-9297)

[3] Source: Wikipedia, “Robert K. Merton”; Accessed 1/25/21.

[4] Reagan had some Irish Catholic ancestry: Wikipedia, “Ronald Reagan.” Accessed 1/29/21.

[5] Image credit: Creative Commons license (“My Great-Grandparents- The Pence’s” by TimothyJ is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

[6] Source: Wikipedia, “Great Famine (Ireland).” Accessed 1/26/21.

[7] Image: Public domain