UNIT III: LEGACIES OF RACIALIZED SLAVERY

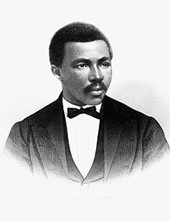

During post-Civil War Reconstruction, lawyer Robert Brown Elliott (1842-1884, above left) served from 1871-74 as U.S. Congressman representing South Carolina’s 3rd District.[1] Elliott was British, born in Liverpool and a graduate of prestigious Eton College. He arrived in South Carolina at age 25 in 1867, where he entered politics and founded the first African American law firm. Despite these achievements, violent southern white backlash against sharing political power with blacks forced Elliott from public life. He died in poverty at age 41 in New Orleans.[2]

Elliott’s career—both tragic and triumphant—illustrates Reconstruction (1865-1877) as the beginning of U.S. federal protection of civil rights of African Americans and other marginalized groups. After Emancipation and a series of congressional civil rights laws enabling southern black political participation, how did whites succeed in depriving most blacks of basic political and civil rights such as voting access and land ownership? Why in these years did the federal government grant millions of acres of public land to whites (Morrill Act, 1862), yet fail to follow through on promises of land (“forty acres and a mule”) for newly freed slaves, paving the way to post-Reconstruction black disfranchisement and debt slavery in sharecropping?[3]

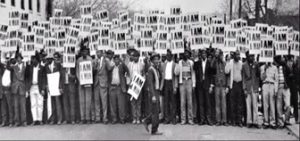

Another wave of congressional civil rights legislation—almost a century later (1950s-60s)—attempted to reincorporate blacks into the nation’s political, economic, and social community. Cold War civil-rights activism was not new, but rather a phase of America’s long civil rights movement: almost 100 years of post-Emancipation, black-led struggle against white nationalism, a struggle that continued after the 1960s. The protest signs (image above right) say “I AM A MAN”—a dignified, emphatic response to most whites’ insistence (in the South, North, and West) that only whites merited full inclusion in the nation.[4] How did the long Civil Rights movement (APAN:I:437) of 1877-1954, together with WWII and Cold War foreign policy, make possible the victories of the modern Civil Rights movement (1954-1968)? What were similarities and differences between northern and southern versions of racial apartheid? What is the relationship between civil rights legislation (law, theory) and real-world experience (custom, practice)?

Chapter 8 Learning Objectives

8.1 Slavery and Civil War Causation

- Explain the relationship between slavery and the Civil War

8.2 Reconstruction: Origins of Modern Civil Rights, 1865-1877

- Explain the significance of the Reconstruction era to civil rights history

- Distinguish federal from state citizenship

- Describe an example of Reconstruction-era federal Civil Rights legislation

- Describe an example of Reconstruction-era Supreme Court decisions

8.3 American Apartheid: Black Exclusion and White Terrorism, 1877-1968[5]

- Describe how southern U.S. and South African apartheid were similar

- Describe major features of southern U.S. apartheid (aka Jim Crow)

- Define lynch law

8.4 Cold War Civil Rights[6]

- Understand the Cold-War context of modern Civil Rights achievements

- Compare and contrast Reconstruction-era (1865-77) and Cold War-era (1945-91) civil rights legislation

Chapter 8 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

Reconstruction: the post-Civil War period (1865-77) of the victorious North’s political re-integration of the defeated South into the Union

debt slavery: a form of unofficial slavery in which creditors coerce or entrap a social group in debt for generations. E.g., sharecropping in the post-Civil War South.

Cold War: the global ideological conflict (1945-91) between the U.S. (capitalism) and Soviet Union (communism).

the long civil rights movement: the decades-long, black-led social movement to secure full citizenship for African Americans. It was the context of the modern Civil Rights movement of the 1950s-60s.

American apartheid: racial segregation, either de jure (by law) or de facto (in fact). Post-Civil Rights America (post-1970) remained highly segregated in fact, though not in law, in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces.

national citizenship: the legal status of citizen of the United States

state citizenship: the legal status of citizen of a U.S. state (e.g., Ohio)

de jure: legal phrase meaning “by law, officially, in theory”

de facto: legal phrase meaning “in fact, in practice”

caste: an especially rigid form of social stratification. The higher-caste group makes upward social mobility very difficult for the lower-caste group (e.g., whites and blacks during American apartheid).

Red Summer: white terrorism in 1919 in dozens of U.S. cities. (“Red” means “bloody.”)

lynch law: mob rule, vigilantism, terrorism. Extralegal white terrorism was common during the colonial era, antebellum era, and apartheid era. During apartheid, white terrorism (in the South, North, and West) targeted especially African Americans, but also Mexicans, Asians, and white ethnics (such as Jews and Italians).

8.1 Slavery and Civil War Causation

Historical causation is complex, involving interaction among a variety of processes and events. However, for decades the consensus view among professional historians has been that, if assigned to any one single cause, the Civil War was caused by slavery. This is despite the ongoing reluctance of many (white) Americans to admit this conclusion, with its attendant glaring focus on the white supremacy of American political and social life in all phases of U.S. history (Levine 2005:x). It has seemed inconceivable to many whites that African Americans, even as enslaved, could have played such a central role in the nation’s greatest crisis, the Civil War.

Civil War contemporaries frequently viewed slavery as the underlying reason for the sectional polarization—between northern free states and southern slave states—that led to war (APAN:I:374). In all the major events eventuating in war—the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the 1857 Dred Scott decision, John Brown’s 1859 Harpers Ferry raid, Southern secession following Lincoln’s 1860 election victory—the great issue at stake and root of the conflict was slavery (Levine 2005: Afterword).

Given slavery’s enormous importance in antebellum America, this conclusion should not be surprising. As discussed in Chapter 5, the late 1700s was a time of Northern emancipation and doubt about the future of slavery. However, by the early 1800s the South was redoubling its commitment to enslaved labor. Slaveowners dominated the South, and racialized slavery was the foundation of their social, economic, and political power. Due to cotton being the South’s most lucrative cash crop, it was the slaves themselves who produced it who represented the nation’s most valuable property asset. In fact, the dollar value of slaves exceeded the combined value of all the United States’ manufacturing, railroads, and banks. In 1860, the total property value of slaves was about $3.5 billion, or approximately $75 billion in today’s money (APAN:I:262). By the 1850s, the South was deeply invested in and committed to slavery and willing to take extreme political measures—even, as it turned out, secession from the United States and formation of a new federal government, the Confederate States of America—to preserve it. Likewise, despite increasing antebellum northern ideological opposition to slavery, northern industry was tightly linked to southern slavery as supplier of finished products (e.g., shoes and hats worn by slaves) and purchaser of southern cotton.

The view from above—that of contemporary elites—provides much evidence that slavery was perceived as causing southern secession (between December 1860 and February 1861). Americans had long justified slavery in terms of white supremacy. In March 1861, Alexander Stevens, the Confederacy’s Vice President, voiced this ideology to explain the connection between secession and slavery. The new Confederacy’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man, that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This our new government is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth” (quoted in Levine 2005:228). Stevens’ “Cornerstone Speech” portrays slavery and its preservation as the raison d’être of the new southern nation. Similar is the view from below: ordinary soldiers’ perspectives during the war. Slavery often appeared to northern and southern enlisted men to be the reason for the war (APAN:I:400). Relatedly, many African American men themselves served as Union soldiers: by 1865, almost 200,000 (Levine 2005:240).

White reluctance to assign slavery the preeminent role in causing the Civil War developed soon after Appomattox. Facing intense postwar antislavery public opinion, by the 1870s and 80s apologists of the Confederacy were denying the relationship between slavery and the war, instead inventing a romantic myth about secession as a heroic yet doomed “Lost Cause” (ibid:245). The Lost Cause myth, in turn, helped to smooth the process of northern and southern white reconciliation, and to end Reconstruction by 1877 (Marx 1997). Amnesia about slavery’s centrality to the nation’s greatest crisis (the Civil War) is one of many parallels between post-Reconstruction and post-Civil Rights America today (Blight 2002; Klinkner & Smith 1999).

8.2 Reconstruction: Origins of Modern Civil Rights, 1865-1877

Slavery’s legacies endured long after the Civil War. Abolition (1863) was followed by massive white resistance—especially in the South, but also North and West—to extending (let alone enforcing) equal civil and political rights to African Americans. Reconstruction (1865-77) featured the nation’s first attempts to incorporate African Americans as a group into the federal- and state-level political communities on an equal basis with whites. Extending equal rights to black citizens was a central project of Reconstruction (Klinkner & Smith 1999:90), within the overall context of the victorious North’s political re-integration of the defeated South into the Union. It was an era of racially progressive federal policy, with Republicans dominating southern politics, African Americans participating in electoral processes, and government accepting the duty of protecting the basic rights of black citizens (Foner 1990:247). Thus, the origins of the modern Civil Rights movement (1954-1968) are found in the Reconstruction era.

In key ways, Americans today—in the post-Civil Rights era—continue to live in the watershed of Reconstruction, begun over 150 years ago. Today, with ongoing de facto racial segregation and inequality, Reconstruction remains an “unfinished revolution” (Foner 1988; see also APAN:I:446). It began the task of achieving justice for centuries of white enslavement of blacks—the root cause of the Civil War. After 1970, despite much important progress, the nation again largely retreated from acting on and enforcing its rhetorical support for equalizing civil and political rights for African Americans (Brown et al. 2003; Doane & Bonilla-Silva 2003; Harvey 2007; Kozol 2005; Orfield 1993). Moreover, the post-1970 retreat has recapitulated key aspects of the post-1877 retreat (Klinkner & Smith 1999). In a significant sense, then, post-Civil Rights America began in 1877, not 1970. As in recent decades, official color-blindness played a central role in post-1877 American apartheid (Alexander 2010; Massey & Denton 1993). Accordingly, post-Civil War history offers valuable insight into race relations in today’s era of post-Civil Rights (see Chapters 9-11).

During Reconstruction, such insight comes especially from: (1) congressional legislation incorporating blacks into the nation as equals with whites; and (2) Supreme Court decisions that contributed to U.S. retreat from the enforcement of racial justice, the end of Reconstruction, and the turn toward twentieth-century apartheid (Massey & Denton 1993).

Racial progress: civil rights legislation, 1865-1875. During the Civil War and Reconstruction, the modern federal government and modern American citizenship were born. In effect, the nation transitioned from existence as a plural entity (the United States “are”) to a singular one (“is”). During the war, President Lincoln oversaw the rapid development of a federal government with much greater authority and scope than in antebellum times, including commitment to the ideal of equal rights of Americans as national (not just state) citizens, irrespective of their race (Foner 1990:xvi).

Note the distinction here between national and state citizenship. Federal citizenship refers to one’s legal status as a citizen of the United States, whereas state citizenship is one’s additional legal status as citizen of a particular state (e.g., Ohio, Alabama, California).[7] Prior to 1860, federal citizenship in most areas of life counted for little as opposed to state citizenship. Federal authority over state and local affairs was relatively minimal. Accordingly, northern abolition (first emancipation: see Chapter 5) had occurred in state legislatures: at the state rather than federal level.

By contrast, Reconstruction-era civil rights legislation came from Congress, occurring at the national (federal) level rather than state level. The Civil War tasks of planning, executing, and coordinating Northern war aims had greatly increased the ability and willingness of the federal government (especially the Republican supermajority in Congress) to take bold action on civil rights. This legislation’s initial effectiveness at fully incorporating blacks into the political community was due to the federal government’s newly expanded reach into affairs (e.g., white exclusion of blacks) that had previously been controlled by state and local governments. That is, Congress imposed a legal environment conducive to the growth of multiracial democracy on southern states where most whites were determined to maintain black exclusion.

Table 8.1. Civil Rights Legislation During Reconstruction

| Legislation | Year | Description |

| Thirteenth Amendment

|

1865 | Abolished slavery throughout the United States (APAN:I:422).

|

| Freedmen’s Bureau | 1865 | The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (the Freedmen’s Bureau) managed large-scale federal aid to citizens in the context of Civil War recovery (APAN:I:423).

|

| Civil Rights Act

|

1866 | The first legal guarantee of rights of Americans as national, versus state, citizens (APAN:I:430). The law prioritized “fundamental rights belonging to every man as a free man” over any state law or practice violating such rights (Foner 1990:110).

|

| Fourteenth Amendment | 1868 | Often described as among the most important of all constitutional amendments. The Amendment forbade states from violating persons’ life, liberty, or property without legal due process, or withholding equal protection of the laws (Foner 1990:115). The Amendment provided the legal foundation for many subsequent antiracism actions of the Civil Rights movement (Moore 2008:93).

|

| Fifteenth Amendment | 1870 | The Amendment prohibited state-level obstruction of voting rights “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (APAN:I:434).

|

| The Enforcement Acts

|

1870-71 | Laws providing enforcement measures to civil rights legislation at federal and state levels (Foner 1990:195).

|

| Civil Rights Act | 1875 | The Act sought to guarantee African Americans equal accommodations with whites in public spaces. But its lack of enforcement measures prevented it from having its claimed effect (APAN:I:441).

|

Sources: Adapted from APAN:I; Foner 1990; Moore 2008

Retreat from racial justice: white terrorism and Supreme Court decisions, 1869-1896. When American civil rights legislation has been backed up by the willingness and means to enforce it, progress toward equality has been swift (Klinkner & Smith 1999). Enforcement was essential to early Reconstruction’s successes, which made major strides toward multiracial democracy (APAN:I:435).

However, as America retreated during the 1870s from commitment to racial justice, civil rights activity became largely rhetorical rather than actual. The effectiveness of federal legislation became severely limited by failure to enforce it. By 1877, several factors had contributed to the retreat: northern Republicans’ fatigue with Reconstruction, a recession, and Democrat-Republican compromise on electing Ohio governor Hayes as President (Marx 1997:13). Likewise, by 1877 whites at state and local levels (especially in the South, where most blacks lived) were becoming increasingly adept at circumventing civil rights laws with indirect, color-blind language not mentioning race. Between the 1880s and 1910, most blacks were excluded from political participation with a panoply of voting restrictions added to state laws and constitutions (Fredrickson 1981:239).

White backlash against black equality began immediately after Emancipation. This took a variety of legal and extralegal forms, but often involved implicit or explicit threats of violence. Antiblack white violence was frequent in the South following the Civil War, as whites attempted to re-impose white supremacy in the new legal, political, and economic environment. Many freedpeople who asserted their basic citizenship rights—exercising freedom of movement away from plantations, challenging contracts, purchasing or renting land, resisting whippings—were physically assaulted or murdered (Foner 1990:53; see also Morrison 1987).

White nationalist terrorism has always thrived on white resentment at multiracial democracy. For example, the Ku Klux Klan was formed during Reconstruction (1866) as a Tennessee social club of Confederate veterans. Its name was based on “kuklos” (or “kyklos”), meaning “circle” in Greek (APAN:I:438). As it expanded into almost all southern states, the Klan used extralegal violence to impose white supremacy by force, terrorizing black and white Republicans during the 1868 presidential election (Foner 1990:146). As southern whites developed more sophisticated and indirect means of re-imposing white supremacy by the 1880s, Klan activity lessened. However, black challenges to white supremacy after WWI and WWII fed rapid growth of Klan membership in the 1920s and 1950s.

Just as significant as white terrorism were the Supreme Court’s racially retrogressive decisions. Especially during the 1860s-1880s, the Court played a key role in assisting the white backlash that ended Reconstruction. Prior to Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)—which definitively began southern Jim Crow segregation—a series of important cases set the stage for American apartheid.

Table 8.2. Supreme Court Civil Rights Decisions, 1869-1896

| Decision | Year | Description |

| Slaughter-House Cases | 1869-73 | The Court reduced the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. It narrowed the rights of national citizenship, while assigning the racially relevant rights to matters of state citizenship (APAN:I:443).

|

| U.S. v. Cruikshank | 1876 | This case further reduced the power of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to protect black civil rights (APAN:I:443; Klinkner & Smith 1999:Ch.3).

|

| Civil Rights Cases | 1883 | The Court overturned the 1875 Civil Rights Act (Foner 1990:247). Justice Joseph Bradley, writing for the majority, asserted that “although African Americans had perhaps merited some assistance right after the end of slavery, ‘there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws’” (Klinkner & Smith 1999:329-30).

|

| Plessy v. Ferguson | 1896 | The Court’s “separate but equal” decision upheld states’ rights over federal intervention in racial segregation. It marked the definitive beginning of post-Civil Rights apartheid.

|

Sources: Adapted from APAN:I; Foner 1990; Klinkner & Smith 1999

In sum, the end of Reconstruction (1877) began a recurring theme in American civil rights history, right up to the twenty-first century: the difference between de jure equality and de facto equality. The Plessy segregationist dictum of “separate but equal,” after all, rhetorically asserted and embraced racial equality. But such equality, as the Court recognized decades later (1954: Brown v. Board), was merely a “legal fiction” (Fredrickson 1981:239), not genuine. Similarly, Congress’s Fair Housing Act (1968) rhetorically embraced open housing (prohibiting racial discrimination in the housing market). But the Act’s enforcement measures were gutted before being voted into law, ensuring that American neighborhoods in subsequent decades would remain highly segregated for blacks (Massey & Denton 1993:83). Likewise, key Supreme Court decisions since the 1960s have supported modern white backlash against modern civil rights legislation.[8] Whether in 1877 or 1968, it has often been America’s failure to enforce its civil rights laws that has prevented de jure equality from becoming de facto equality (Alexander 2010).

8.3 American Apartheid: Black Exclusion and White Terrorism, 1877-1968

As sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois (1903; see Chapter 1) famously predicted, the twentieth century was the century of the color line. American apartheid was whites’ use of racial segregation and color bars following the Supreme Court’s Plessy “separate but equal” decision (1896), especially in the South but also in the North and West (Sugrue 2008).

Although white supremacy was old by 1900, apartheid was new. There were many forms of pre-1900 racial exclusion (e.g., northern and southern state Black Codes). But prior to the twentieth century, whites tended not to strictly segregate African Americans, either in the South or the North (Massey & Denton 1993:10). Between the Civil War and 1900, most blacks continued to live in the South, predominantly in rural debt slavery (sharecropping) but also in cities. In both settings, long traditions of black servants living near white masters slowed the growth of residential segregation. In the North, blacks experienced much exclusion (e.g., see Chapter 5 on Ohio’s Black Laws), but stricter racial segregation was not characteristic of northern schools, neighborhoods, and businesses until after 1900.

By 1900, formal (southern) and informal (northern) racial segregation—apartheid—in neighborhoods, employment, schools, and public accommodations (hotels, restaurants, parks, cemeteries, toilets, drinking fountains, pools, beaches) was becoming common throughout the nation. Twentieth-century segregation took distinctive forms in the South, North, and West. Below, we discuss its major features in the South, highlighting similarities with South African apartheid.

Southern apartheid (aka Jim Crow segregation). The system of formal apartheid in the South, largely in place by 1900, maintained a strict caste division between white and black racial groups (Fredrickson 1981:252). In a caste society, social mobility by the out-caste group (e.g., African Americans) is rendered extremely difficult, with most members kept at the bottom of (or excluded from) social, economic, and political hierarchies (ibid:98; cf. Cox 1948; Wilkerson 2020). Southern state laws and customs restricted blacks’ physical movements, marriage choices, educational options, job options and careers, political participation, etc., all of which blocked social ascent.

Nevertheless, despite the context of white supremacy, southerners of both races had much in common, sharing the same society, economy, legal system, and overlapping cultures (Fredrickson 1981:252). For decades following 1877, the South would contrast with the North as a region of poverty, illiteracy, and ill health and disease (e.g., malaria) (APAN:II:670-71). Federal interventions during the 1930s New Deal brought benefits to southern states. However, southern white elites used states’ rights rhetoric to challenge any federal action threatening racial hierarchy (ibid:671). Although the South’s disprivilege (as compared to the North) affected both races, blacks suffered disproportionately in the three-way relationship among northern whites, southern whites, and southern blacks.

This relationship was paralleled in South Africa by that linking British whites, Dutch Afrikaner whites, and native blacks. In both world regions, twentieth-century apartheid and white racial terrorism greatly magnified the ravages of poverty, disease, and poor education on black and brown people. Likewise, in both South Africa and America white elites had long used white supremacy as a divide-and-rule political strategy to reduce class conflict between themselves and poorer people of both races (APAN:I:438; Levine 2005:249). Even poor whites could participate in “Herrenvolk [master race] equality” (Fredrickson 1981:154) and receive “psychological wages of whiteness” (Du Bois 1903).

Figure 8.1.[9] South Africa is the southernmost country on the continent of Africa, colonized by the Netherlands (1600s-1700s) and Britain (1800s). Apartheid in South Africa resembled that in the U.S., especially in the South.

Jim Crow’s characteristic features included debt slavery, black convict leasing, and white terrorism. Below, we discuss the last of these:

White terrorism. Following widespread and frequent antiblack violence during Reconstruction, the violence continued throughout the apartheid period (1877-1968). White violence was just the most explicit and crudest form of black repression, working together with officially color-blind legislation and judicial decisions to limit and control black participation in public life, especially in the South (APAN:II:517; Klinkner & Smith 1999:90-91). For example, although in 1896 more than 130,000 black Louisianans voted, this number plummeted to 1,342 in 1904. In the same period, black voting turnout dropped over 90% in North Carolina and Alabama, and over 66% in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas (Klinkner & Smith 1999:104).

White terrorism took three main forms: individual harassment and threat, lynching, and racial massacre. Following World War I and increasing black migration to northern cities (the start of the Great Migration), antiblack riots and massacres occurred throughout the country—examples are East St. Louis, Illinois (1917); Springfield, Ohio (1921); and Tulsa, Oklahoma (1921). The single worst year was 1919—Red Summer—when “white supremacist terrorism and racial riots took place in more than three dozen cities across the United States…”[10]

Lynching, however, was perhaps the most emblematic form of white nationalist terrorism. “Lynch” law refers to vigilante action bypassing official legal processes and violating victims’ due process rights (Fifth Amendment). Victims were merely suspected or informally accused of a crime or noncriminal behavior, after which mob violence took over. Regarding the U.S. apartheid period, lynching means murder by a group of vigilante white males of one or several black males. This typically was death by hanging or being burned alive, but also frequently involved torture (e.g., repeated branding, attack by dogs) and other forms of terror (APAN:II:516). Between 1877 and 1950, American whites lynched about 4,400 black victims.[11] Extralegal racist custom ran parallel with the rule of law, enacting deadly terrorist violence against innocent citizens.[12]

Table 8.3. White Lynchings of Blacks in the U.S., 1882-1905

| Year | Lynchings | Year | Lynchings |

| 1882 | 49 | 1894 | 134 |

| 1883 | 53 | 1895 | 113 |

| 1884 | 51 | 1896 | 78 |

| 1885 | 74 | 1897 | 123 |

| 1886 | 74 | 1898 | 101 |

| 1887 | 70 | 1899 | 85 |

| 1888 | 69 | 1900 | 106 |

| 1889 | 94 | 1901 | 105 |

| 1890 | 85 | 1902 | 85 |

| 1891 | 113 | 1903 | 84 |

| 1892 | 161 | 1904 | 76 |

| 1893 | 118 | 1905 | 57 |

Source: Klinkner & Smith 1999:91

Figure 8.2.[13] White terrorism and the lynching of Emmett Till, age 14. Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam kidnapped, tortured, and shot Till in rural Mississippi in 1955. The mutilated corpse shows how Till’s eyes had been gouged out. An all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty. Protected from further prosecution (double jeopardy), the two white men publicly admitted to the crime in a 1956 interview with Look magazine.[14]

8.4 Cold War Civil Rights

The Cold War was the international context of the modern Civil Rights movement (Dudziak 2000). The achievements of 1954-68 came after decades of struggle by the long civil rights movement, with crucial turning points being World War II and early Cold War foreign policy (Klinkner & Smith 1999).

Domestic racial apartheid was a serious problem for U.S. foreign policy in the Cold War. This was the global ideological conflict (1945-91) between the U.S. (capitalism) and Soviet Union (communism). Though “cold” (not open warfare between the two superpowers), it spawned many regional hot wars (e.g., Korea, 1950-53; Vietnam, 1955-75; Afghanistan, 1979-89). U.S. racial progress during the 1940s-60s was often motivated by foreign policy concerns for America’s image and prestige in the eyes of the Third World (APAN:II:736).

Though the Cold War context made racial progress possible, the Civil Rights movement itself was the primary force responsible for ending formal U.S. apartheid by 1968. The movement relied on many ordinary people, especially blacks but also whites, in the South and North (Morris 1986). Many of these volunteers took risks and made sacrifices for the cause of racial justice; some gave their lives. The movement’s leaders represented a range of political and ideological positions. For example, integrationists tended toward politically moderate positions and included Ella Baker, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Pauli Murray, and A. Philip Randolph. Black nationalists and others, by contrast, took more politically radical positions and included Louis Farakhan, Malcolm X, Huey Newton, and Kwame Ture (aka Stokely Carmichael).

Table 8.4. Federal Responses to the Civil Rights Movement

| Year(s) | Government branch | Description of events |

| 1944, 1946, 1948 | Judicial (Supreme Court) | The Court’s decision in Smith v. Allwright (1944) represented a victory for the NAACP. The case prohibited Democratic whites-only primaries. Likewise,

Morgan v. Virginia (1946) ruled against segregation in interstate bus transportation. In Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the Court ruled against the enforceability of antiblack housing covenants, in which white homeowners agreed among themselves not to sell to blacks (APAN:II:757).

|

| 1946 | Executive | By executive order, Truman created the President’s Committee on Civil Rights (ibid:757).

|

| 1954

|

Judicial (Supreme Court) | In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the Court reversed the 1896 Plessy “separate but equal” ruling (ibid:758). |

| 1957 | Executive | Arkansas Governor Faubus defied school desegregation. This blatant resistance forced a reluctant President Eisenhower to act by enforcing desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock (ibid:759).

|

| 1957 | Legislative | The first Civil Rights Act since Reconstruction. The 1957 law formed a federal commission on civil rights to counter discrimination, especially in voting (ibid:759-60).

|

| 1964 | Legislative | The landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act effectively ended de jure Jim Crow (ibid:786).

|

| 1964 | Legislative | The Twenty-fourth Amendment ended the poll tax, which had historically frequently been used to limit black voting.

|

| 1965

|

Legislative | A landmark civil rights law, like 1964’s Civil Rights Act. The Voting Rights Act prohibited laws and customs obstructing black voting in the South (ibid:776).

|

| 1967 | Judicial | The Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia ruled as unconstitutional state miscegenation laws. Such laws prohibited interracial sex and marriage.

|

| 1968 | Legislative | The Open Housing Act of 1968 mandated open housing. It outlawed racial discrimination in housing markets.

|

| 1970 | Legislative | Voting Rights Act

|

| 1972 | Legislative | Equal Employment Opportunity Enforcement Act

|

Sources: Adapted from APAN:II; Klinkner & Smith 1999:281-83,294; Telles & Ortiz 2008:92

Notable about Table 8.4 are both the extended time frame (almost three decades between 1944 and 1972) of modern Civil Rights achievements, and the actions of all three federal branches (judicial, executive, legislative). Both features are indications of the massive extent of white resistance at state and local levels to black civil rights and desegregation (Klinkner & Smith 1999:287). Moreover, the federal government resisted as much as supported racial change. For example, from 1956 to 1971 the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) surveilled, harassed, infiltrated, and disrupted the activities of civil rights leaders and groups.[15] Given extensive similarities of the modern Civil Rights era with Reconstruction (see Chapter 9), post-Reconstruction (1877) retreat from equality warrants critical thinking about post-Civil Rights (1968) claims about the “end” of racial injustice in America.

Chapter 8 Summary

Chapter 8 introduced Unit III (Legacies of Racialized Slavery) with a historical overview of Reconstruction and American Apartheid. Section 8.1 explained the consensus view of professional historians in recent decades that slavery was the root cause of the Civil War.

Section 8.2 presented Reconstruction (1865-77), the period of U.S. history following the Civil War. Reconstruction faced the double task of national reconciliation and full incorporation of black freedpeople into the nation. By 1877, the nation had decisively retreated from the latter goal in favor of northern and southern white reconciliation.

Section 8.3 summarized American Apartheid (1877-1968), the post-Reconstruction period of white exclusion of blacks. Racism worsened in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with northern whites isolating migrant blacks in urban ghettos for the first time in U.S. history. Southern apartheid resembled in key aspects South African apartheid. Characteristic features were debt slavery, black convict leasing, and white terrorism.

Section 8.4 discussed the achievements of the Civil Rights movement during the Cold War. These victories came after decades of struggle by the long Civil Rights movement, with the crucial turning points being World War II and early Cold War foreign policy.

[1] Image: Public domain

[2] Source: Wikipedia, “Robert B. Elliott.” Accessed 2/4/21.

[3] Source: Wikipedia, “Morrill Land-Grant Acts.” Accessed 6/7/21.

[4] Image: Public domain

[5] Source of phrase “American Apartheid”: Massey & Denton 1993.

[6] Source of phrase “Cold War Civil Rights”: Dudziak 2000.

[7] Residents of U.S. territories (e.g., New Mexico, 1848-1912; Puerto Rico, 1917-present) generally have had national citizenship without state citizenship. For example, Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, though Puerto Rico is not a state.

[8] Examples include Terry v. Ohio (1968, increased police powers to stop-and-frisk, from “probable cause” to “reasonable suspicion”); Milliken v. Bradley (1974, blocked suburban desegregation); Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978, blocked use of racial quotas in affirmative action); Graham v. Connor (1989, applied an “objective reasonableness” standard to officers’ actions, supporting police use of deadly force); Whren v. U.S. (1996, allowed racial profiling by police via “pretext” traffic stops). See Alexander 2010.

[10] Source: Wikipedia, “Red Summer.” Accessed 6/8/21. See also Klinkner & Smith 1999:114-15.

[11] Source: Equal Justice Initiative. https://eji.org/reports/lynching-in-america/

[12] Cf. white racism in the lives of black jazz musicians: Davis and Troupe 1990; Hasse 1993; Shipton 2001.

[13] Left and right images: Public domain

[14] Source: Wikipedia, “Emmett Till.” Accessed 4/7/21. See also Hohle 2018: Ch.1.

[15] Source: Wikipedia, “COINTELPRO.” Accessed 6/18/21.