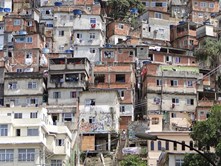

Chicago South Side, 1974 (left); Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (right) [1]

The images above illustrate post-Civil Rights America in historical and comparative (international) perspective. For decades, communities like Chicago’s South Side, Roxbury (Boston) and East St. Louis were black ghettos: monoethnic slums of concentrated disadvantage. Though still nonwhite today, some ghettos since the 1970s have been transformed by Hispanic immigration—e.g., Roxbury, Harlem (New York), Camden (Philadelphia), Compton (Los Angeles). By contrast, others (e.g., East St. Louis: 98% black) remain hypersegregated and overwhelmingly black. In both kinds of ghetto, non-Hispanic white residents remain few.[2] Similarly, Brazilian slums (favelas) today remain mostly black and brown (Telles 2004:194-95).

Police activities in nonwhite U.S. and Brazilian slums have often featured repressive violence. Brazilian police-civilian interactions are much more likely to end with the civilian wounded or dead when the civilian is nonwhite (rather than white). In São Paulo state alone, military police have killed hundreds of civilians each year since the 1980s (ibid:166). Across Brazil, thousands of Brazilians are killed every year by police. Most of these citizens are nonwhite (black, brown) and poor. About 5,800 Brazilians were killed by police in the single year of 2019 (McCoy 2021).

Brazil’s official colorblindness, state policy since the 1930s despite increasing governmental acknowledgment (post-1990) of ongoing racial injustice, discourages Brazilians from analyzing such facts in terms of race or skin color. For almost a century, color-blind ideology has allowed white Brazilians to blame the poor life chances of black and brown Brazilians on class inequality alone, rather than in combination with racial inequality (Chasteen 2001; Marx 1997). How does present-day police abuse connect to the longer history of racial injustice in Brazil and the U.S.? What costs and benefits has official colorblindness brought to race relations in these nations? How has racial injustice in these countries changed across the decades, and how has it stayed the same?

Chapter 9 Learning Objectives

9.1 Cycle of U.S. Racial Progress and Retreat

- Define ghetto

- Describe examples of racial progress and retreat in American history

- Describe three parallels between the post-Reconstruction (1877) era and post-Civil Rights (1968) era

9.2 Colorblindness: Brazil and the United States

- Define colorblindness

- Explain similarities and differences in color-blind ideology between Brazil and the U.S.

9.3 Race and Class

- Define life chances

- Explain why most sociologists see race-class intersectionality as an ongoing source of inequality in post-Civil Rights America

9.4 The Principles/Policy Paradox

- Explain what survey researchers mean by the principles/policy paradox regarding race

Chapter 9 Key Terms (in order of appearance in chapter)

ghetto: a community of nonwhites excluded (formally or informally) from neighboring white areas. Until 1900, this term referred to segregated Jewish areas of European cities. (“Ghetto” was the medieval Jewish quarter of Venice.) Brazilian ghettos are called favelas.

hypersegregation: almost complete residential segregation by race, as in cities in which most whites and most blacks live in different neighborhoods (e.g., whites in suburbs and blacks in inner-city ghettos). Many U.S. metropolitan regions, especially in the North, remained racially segregated in the 1970s, 80s, and beyond, with several being hypersegregated (Massey & Denton 1993).

colorblindness: the political claim (as in Brazil, South Africa, and U.S.) that society no longer faces serious problems of racial discrimination, and that policies explicitly designed to benefit nonwhites are unnecessary and/or harmful

life chances: the likelihood of social well-being. Key indices include income and wealth, occupational prestige, level of education, mental and physical health (e.g., infant mortality, life expectancy), quality and location of housing, relation to criminal justice, political representation, social mobility.

Nelson Mandela (1918-2013): anti-apartheid revolutionary incarcerated by South Africa for 27 years (1964-1990). He played a central role in South Africa’s transition from formal apartheid, serving as President from 1994-1999 (see Chapter 4).

disparities (in life chances): group inequalities in likelihood of social well-being. (“Dis-parity” literally means inequality or discrimination: unfair, differential treatment.) In a society lacking white normalization or racial bias, we would expect comparable or similar processes and outcomes across racial-ethnic groups (all other things being equal: e.g., class inequality).

sociology of race relations: the social science of white racial domination across societies with colonial and national histories of white supremacy. Three important comparative cases are Brazil, South Africa, and the United States (Telles 2004:2).

racial democracy: a color-blind ideology (especially 1930-1990) emphasizing shared Brazilian national identity and claiming the absence of racism in Brazil

principles/policy paradox: the survey research finding that, after 1970, most white Americans have increasingly held abstract racially egalitarian principles, while simultaneously opposing concrete public policy that would promote such principles

9.1 Cycle of U.S. Racial Progress and Retreat

By the early twenty-first century, the United States and South Africa—once bastions of racial apartheid—had had black presidents. Barack Obama served as American President from 2009-2017; in South Africa following Nelson Mandela’s presidency (1994-1999), several other black men have served as President. Since the end of de jure white supremacy (1990 in South Africa, 1968 in America), both nations have experienced great racial progress, with larger black middle classes (Keller 2005) and racially tolerant views expressed by many whites on academic surveys (Schuman et al. 1997). To many people, such changes have indicated that antiblack racism and white supremacy have sufficiently weakened as to no longer be serious social problems. They see today’s ongoing white-black disparities in life chances—legacies of centuries of slavery and apartheid—as mostly due to socio-economic class inequality, not race.

However, most academic experts on race tend to disagree with this view. Especially since the 1990s, an abundance of empirical race research in sociology, criminology, demography, psychology, political science, and history has led most contemporary professional social scientists of race to conclude that racial injustice has been largely ongoing rather than overcome—not only in the U.S., but in many countries with legacies of racialized inequality such as South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico (Fredrickson 1981:280; Lewis & Diamond 2015:xvii-xviii; Marx 1997:271; Massey & Denton 1993:15-16, 186). Moreover, as in the 1950s-60s, reported attitudes on race relations by U.S. whites and blacks continue to display large intergroup differences of opinion (Feagin 2020; see Chapter 11). If white supremacy had largely been overcome, wouldn’t blacks and whites tend to see race relations more similarly than differently?

Despite the great importance of modern civil rights achievements (see Table 8.4), these advances had limitations, especially in enforcement, that are (even) more evident today with fifty years of hindsight (Bonilla-Silva 2001, 2015; Goldberg 1997). For example, President Johnson in 1965 acknowledged the limits of civil rights legislation, stating that “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others’” (quoted in APAN:II:814). Accordingly, the overall purpose of Chapters 9-11 is to explain why most sociologists see race as a continuing social problem in America. Chapter 9 begins this explanation by discussing insights into contemporary race relations offered by historical and comparative (international) perspectives.

Key insights about post-Civil Rights America can be gleaned from the pre-1960s U.S. history reviewed in Chapters 5-8. This is because the 1950s-60s Civil Rights era was not the first major period of American racial reform. According to Klinkner and Smith (1999), this history shows a cyclical pattern, in which a period of racial progress is followed by white retreat from willingness to sustain such reform. Given the overwhelming power U.S. whites have always had (as a group) vis-à-vis blacks, white commitment has always been necessary for such progress; blacks have never had the material resources sufficient for unilateral political action to succeed. Thus, white retreat has been responsible for ending reform periods, initiating long eras of retrenchment of the racial status quo. Later forms of inequality differed importantly from prior forms—for instance, northern de jure freedom (e.g., final emancipation of New York slaves in 1827) was better than northern slavery.[3] But subsequent periods of retrenchment have, in each historical case to date, always fallen short of the white commitment necessary for full, de facto inclusion of blacks in American society.

Klinkner and Smith (1999:73) note that U.S. history displays three eras of significant racial reform: the Revolutionary era, the Civil War era, and the WWII-early Cold War era. Three sources of progress during these eras were (1) a major war in which blacks participated; (2) a war enemy that U.S. elites countered by emphasizing egalitarianism at home; and (3) pressure from antiracism groups on U.S. elites to match egalitarian rhetoric with action (ibid:73). Given similarities with previous retreats from racial inclusion following the Revolutionary War (after 1820) and the Civil War (after 1877), Klinkner and Smith argue that today’s post-Civil Rights era (after 1980) is likewise a retreat phase.

Table 9.1. Cycle of U.S. Racial Progress and Retreat

| War era | Enemy | Black military participation | Progress toward racial equality | Start of retreat from racial equality

|

| Revolutionary War (1775-1783) | British Empire | 5,000-8,000 black U.S. soldiers (out of total force of 300,000) (Klinkner & Smith 1999:19). | Northern state emancipations; southern manumission made easier

|

By 1820 (Missouri Compromise) |

| Civil War (1861-1865) | Confederate States of America | North: by war’s end, 180,000 blacks had served in Union armies, and thousands in navy (ibid:70). By war’s end, 12.5% of Grant’s army was black (ibid:70-71).

South: Confederate Congress (March 1865) allows slave enlistment into army (ibid:70). Slaves had already provided much labor support to Confederate armies.

|

Federal Emancipation; Reconstruction amendments; Civil Rights laws | By 1877 (Compromise of 1877 and southern redeemer governments end Reconstruction) |

| WWII (U.S. at war 1941-45); early Cold War (1946-72); Korean War (1950-53)

|

Axis Powers, then global Communism | Black participation in WWII and Cold War conflicts. In armed forces as soldiers, sailors, aviators. In home-front war production industries. | 1940s-60s Supreme Court decisions; Civil Rights laws | By 1980 (Reagan presidency and 1960s-80s Supreme Court decisions supporting white backlash) |

Source: Adapted from Klinkner & Smith 1999

In each era, whites end reform in similar ways. White rhetoric—whether in 1820, 1877, or 1980—justifies retreat by describing racially progressive policies as having “failed” (Hohle 2018). Whites blame blacks themselves (communally and individually “blaming the victim”)—rather than social structures created by white supremacy—for ongoing exclusion, poverty, and criminalization (Armenta 2017). Whites create or tolerate new forms of inequality: e.g., northern Black Codes following northern slavery, de facto debt slavery following de jure slavery, de facto segregation and racialized mass incarceration following de jure segregation. In each era, most whites (and some blacks) celebrate the new racial status quo as having “solved” past problems.

Parallels between post-Reconstruction (1877) and post-Civil Rights (1968) America. Today, we live in the post-Civil Rights era. That is, the modern civil-rights reform era ended by 1980. Most analysts describe the 1970s as a time of transition to the current neoliberal (i.e., neoconservative) era, starting by 1980 with President Reagan (Kozol 1991; Morris 1986).[4] In modern white resistance (1960s-90s) to racial change, Klinkner and Smith (1999:328-45) point to numerous parallels with the post-Reconstruction (after 1877) era of white resistance to racial change:

- Renewal of demands for state and local authority rather than national authority;

- Rise of color-blind (rather than color-aware) public policy;

- Prominence or return of laissez-faire (minimal government) principles;

- Prominence or return of “scientific” racism;

- Claims seeking to link nonwhites to inherent or endemic “criminality”;

- Increasing support for restrictions on immigration;

- Decreasing support for enforcement of existing civil rights laws;

- Calls for voting restrictions that disproportionately affect nonwhites;

- Declining interest in high quality, racially integrated public education;

- Among African Americans, declining interest in black-white integration and rising attraction of black nationalism and separatism;

- Declining commitment to action (vs. rhetoric) on racial equality by racially progressive major parties: Republicans post-1877, Democrats post-1968.[5]

Although the meaning of such parallels is up for debate, it is difficult—given the undeniable resilience of white supremacy in U.S. history—to simply dismiss them.

9.2 Colorblindness: Brazil and the United States

As with historical analysis, insight into contemporary race relations comes from comparative (cross-national) analysis. White-black race relations have taken different forms in various countries. For example, racial classification often works differently in the U.S. and Latin America (see Chapters 3 and 7). Accordingly, the sociology of race relations considers more than just the U.S., encompassing race relations globally (Telles 2004:2; cf. Pettigrew 1980). Cross-national analysis offers understanding of what is and is not unique about race in the United States, helping to appreciate both the victories of the modern Civil Rights movement and their limitations.

Like South Africa, a fruitful comparative case for studying U.S. race relations is Brazil. The U.S. and post-apartheid South Africa were not the first societies to claim colorblindness. These nations may have much to learn from Brazil, a society with a longer experience with officially race-neutral policies (Telles 2004:66).

Figure 9.1.[6] Brazil, geographically larger than the continental U.S., is the largest country in Latin America (Telles 2004:19). It was colonized by Portugal, in contrast to the Spanish colonization of most other Latin American nations. Whereas most Mexicans speak Spanish, most Brazilians speak Portuguese.

In key ways, U.S. color-blind discourse has paralleled 1930s-1980s Brazilian racial democracy. This is a color-blind ideology emphasizing shared Brazilian national identity and claiming the absence of racism in Brazil (Chasteen 2001:315; Marx 1997:273). Describing colorblindness as an “ideology” (see Chapter 2) emphasizes that it is not simply a putatively desirable state of affairs (“a world beyond race”). Rather, colorblindness is a political worldview asserting that society no longer faces serious problems of racial injustice, and that policies explicitly benefitting nonwhites are unnecessary and harmful (Gómez 2018:xii-xiii; Hohle 2018). Colorblindness claims that:

(1) “[M]ost people do not even notice race anymore;

(2) [R]acial parity has for the most part been achieved;

(3) [A]ny persistent patterns of racial inequality are the result of [nonwhite] individual and/or group-level shortcomings rather than structural ones; …

(4) [T]herefore, there is no need for institutional remedies…to redress persistent racialized outcomes.”[7]

Like any political ideology, colorblindness has important social consequences that need to be made explicit to be understood (Holt 1992:25).

Especially after 1930 (President Vargas era), Brazilian calls for greater civic and political inclusion of nonwhites were met by color-blind assertions that Brazilian racism no longer existed. Under the military dictatorship of 1964-1985, it was even illegal to study race in Brazil (Chasteen 2001). Official colorblindness blocked the collection of race-relevant statistical data that might have challenged Brazilian nationalism and elite white interests. The absence of demographic evidence (due to the ban on race analysis) made it difficult to counter claims that racially ameliorative policies were unnecessary (Loveman 2014; Marx 1997:168-69). More recently, Brazilian society has undergone a widespread reckoning on race, in which antiblack racism has become widely acknowledged. In Brazilian social science, race became an accepted area of study during the 1990s. Since then, many quantitative studies have documented and analyzed Brazil’s ongoing racial injustices (Telles 2004:55).

The Brazilian example shows that, although many Americans are accustomed to thinking of colorblindness as unambiguously racially progressive, the reality is more complex (Alexander 2010; Bonilla-Silva 2001). Although U.S. legal justice is blind (e.g., to socio-economic class), everyone knows that this ideal often goes unrealized in practice. Likewise, the achievement of color-blind law has been an important step toward racial justice; however, much social scientific evidence suggests that color-blind (like class-blind) justice is often more ideal than reality (Gonzalez Van Cleve 2016). The real meaning of colorblindness is all too often paying rhetorical lip service to de jure ideals, while turning a blind eye to ongoing de facto racial inequality. For these reasons, historical and comparative scholars familiar with colorblindness as a tool of white supremacy have paid careful attention to its growth in the U.S. after 1970 (Marx 1997:273-74).

Indeed, as in twentieth-century Brazil, colorblindness was a common white political strategy in many 1800s post-emancipation societies (e.g., Barbados: Lamming 1953; Cuba: Ferrer 1999, Fuente 2001; Jamaica: Holt 1992). Former slaveowners sought to retain control of newly “freed” black labor, but now in a “modern” (formally color-blind) way consistent with antislavery and laissez-faire economic principles (Scott 2000). Likewise in the post-emancipation South, elite whites used colorblind state legislation to maintain economic, political, and social control over blacks. After 1877, northern white Republicans joined Southern white Democrat calls for policy that was racially neutral, rather than racially aware. As the Supreme Court asserted in the 1883 Civil Rights Cases overturning the 1875 Civil Rights Act, “blacks must cease ‘to be the special favorite of the laws’” (Foner 1990:247). Thus, racially neutral policy neither explicitly benefiting nor harming nonwhites—colorblindness—is entirely consistent with retreat from racial equality (Klinkner & Smith 1999).

9.3 Race and Class

As we’ve seen, social identities are intersectional: complex and overlapping (Chapter 1). Race and socio-economic class are demographic variables of particular interest to social scientists. This is because they are among the most important determinants of social position—one’s placement in the social organization and distribution of power, resources, and opportunities (Wright & Rogers 2011).

Regarding class, all other things being equal, you’re more likely to receive these social goods (power, resources, opportunities) if you come from a wealthy rather than a poor family (Domhoff 2017). Despite U.S. de jure equality of opportunity, the de facto reality is that class background (e.g., as measured by parent’s occupation, family wealth, education) is a key determinant of children’s life chances: the likelihood of social well-being (Khan 2018). Key indices include income and wealth, occupational prestige, level of education, mental and physical health (e.g., infant mortality, life expectancy), quality and location of housing, relation to criminal justice, political representation and responsiveness, and social mobility.

Chapter 1 noted that intersectional theory observes that members of social groups may experience advantage and disadvantage simultaneously, in comparison to members of other groups (Wingfield 2013:21). Likewise, having multiple marginalized identities (e.g., poor, non-citizen, Latina, disabled, woman) tends to compound life difficulties. Race and class, then, among other variables, interact in their impact on individuals’ life chances. As with European Americans, Asian Americans, or any other racial group, race and class work together to shape the experience of African Americans. The ongoing poor life chances of this group, as compared to the white group, are not due solely to either variable but to their interaction (APAN:II:852; Massey & Denton 1993:219-20; Telles 2004:116; Telles & Ortiz 2008:135). As Chapter 3 noted (individuals vs. groups), such social determinants are not destiny: some individuals are unrepresentative of their racial and class background. Rather they pertain to overall group characteristics. In sum, ongoing white-black racial disparities in today’s post-Civil Rights era cannot be explained as mostly due to class inequality alone. Racial inequality continues to play an important role, though its mechanics have changed in post-1970, officially colorblind society.

Likewise in Brazil, residential segregation by race was long misunderstood as solely due to class, with race not being relevant (Telles 2004:3). As we’ve seen, in recent decades Brazil has increasingly acknowledged the abundant demographic evidence suggesting that the country’s extreme racial disparities cannot be explained by class inequality alone. Racism, both psychological and social structural, continues to severely limit the life chances of black and brown Brazilians, as compared to white Brazilians (ibid:220).

Still central to race relations today, race and class have always had an important relationship, ever since the beginnings of European global colonization. “Race,” after all, was invented by Western Europeans to explain and justify global colonization: first to themselves, then to colonized others (Chapters 4 and 7). White supremacy was never just about ideas; rather, it was an ideology justifying and protecting whites’ economic interests (Lewis & Diamond 2015:155). The whole point of racialized slavery (racializing an economic relationship of absolute domination) was to maximize economic control over an exploitable source of cheap labor, in the context of profit-oriented agricultural capitalism (Dunn 2000). Emancipation—in Jamaica (1834), the U.S. (1863), Cuba (1880s), Brazil (1888)—disrupted this control, and white elites quickly developed colorblind means to reassert it.

Given these regions’ legacies of racialized slavery—in which the slave class was defined in terms of black race—how should post-abolition policy aim to equalize life chances of blacks and whites? Is color-awareness or color-blindness best? This thorny Reconstruction-era problem, hinging on the intersectionality of race and class, is a central part of what historian Thomas Holt (1992) calls the “problem of freedom” in post-emancipation societies. As noted, Americans in the twenty-first century were still grappling with this old policy problem of Reconstruction, our “unfinished revolution” (Foner 1988).

9.4 The Principles/Policy Paradox

Like research on the race-class relationship, a major finding of public opinion researchers since the 1990s has contributed to better understanding of race relations in post-Civil Rights America. This is the principles/policy paradox (Klinkner & Smith 1999:324; Schuman et al. 1997).

Americans after 1970 have increasingly expressed support on academic surveys for abstract principles of racial integration and equal opportunity. For example, asked in terms of principles—“[S]hould people be able to attend any school?”—whites tend to express support. However, when asked in terms of more specific public policy—“[S]hould the government make interventions to ensure integrated schools?”—whites tend to express opposition (Lewis & Diamond 2015:209).

A tension here is between widespread support for color-blind equality of opportunity, on the one hand, and equally widespread antipathy to federal governance, on the other. However, the paradox is that color-blind equality (what whites support) has—ever since the Civil War—usually been promoted in U.S. history by federal intervention in state and local affairs (what many whites oppose). After all, it was sustained federal action for almost thirty years (1944-1972) that made modern Civil-Rights-era victories possible. Supreme Court action (e.g., 1954 Brown v. Board), Presidential action (e.g., Eisenhower’s 1958 use of federal troops to force Little Rock school desegregation), and Congressional action (e.g., 1964 Civil Rights Act) all exemplify the very government interventions that many whites after 1970 have opposed (Klinkner & Smith 1999:315-16). As in the 1950s and 60s, white Americans post-1970 often remained ambivalent or opposed to government action that would address ongoing obstacles to racial inclusion.

One example of the paradox is open housing—prohibition by federal law since 1968 of racial discrimination in the housing market. Even as late as 1980, three-fifths (60%) of whites reported themselves opposed to legislation mandating open housing; yet the Fair Housing Act had already been the law of the land since 1968 (Massey & Denton 1993:92). Such ambivalence shouldn’t be surprising: as a group, whites benefited in many ways from pre-1970 white supremacy. In the post-1970 era, white opposition to policy proposals for reducing racial disparities in life chances remained a serious obstacle to achieving U.S. racial equality of opportunity (Doane & Bonilla-Silva 2003).

In sum, the principles/policy paradox exemplifies parallels between today’s post-Civil Rights era and the post-Reconstruction era (Klinkner & Smith 1999). Both eras saw equality rhetoric (abstract words) increasingly diverge from meaningful equality policy (concrete action).

Chapter 9 Summary

Chapter 9 discussed post-Civil Rights America, using U.S. history and international comparisons to achieve insight into contemporary race relations. Section 9.1 examined the contemporary relevance of the history of U.S. racial progress and retreat. Many parallels are evident between the post-Civil Rights (1968) and post-Reconstruction (1877) eras, suggesting that the contemporary era may be best understood as a time of overall retreat of white commitment to racial equality.

Section 9.2 introduced colorblindness, comparing and contrasting U.S. race relations in the post-Civil Rights era with South Africa and Brazil. Given Brazil’s familiarity with colorblindness since the 1930s, the U.S. may have much to learn from Brazilian experience.

Section 9.3 examined the relationship between inequalities of race and class. The intersectionality of these social identities and positions means that both have contributed to nonwhite disadvantage as compared to whites. Claims that dramatic disparities in U.S. life chances between African Americans and European Americans are primarily due to class, not race, were not new post-1968, but rather date to Reconstruction.

Section 9.4 examined the “principles/policy” paradoxical finding of social survey researchers in the post-Civil Rights era. Whereas Americans have increasingly expressed racially tolerant attitudes (principles) on academic surveys, they simultaneously express opposition to political policies that would put those principles into action. The paradox exemplifies a key parallel between today’s post-Civil Rights era and the post-Reconstruction era: the divorce of equality rhetoric from meaningful equality policy.

[1] Left image: Public domain. Right image credit: Creative Commons license (Leon petrosyan – Own work: Favela not far from Copacabana)

[2] Source: Wikipedia, accessed 6/18/21:

Roxbury: 57% African American, 28% Hispanic, 8% White (2007-11 American Community Survey).

Harlem: 63% African American, 22% Hispanic (any race), 9.5% White (2010 U.S. Census).

Camden: 48% African American, 47% Hispanic (any race), 18% White (2010 U.S. Census).

Compton: 33% African American, 65% Hispanic (any race), 0.8% White (2010 U.S. Census).

East St. Louis: 98% African American, 1% Hispanic (any race), 1% White (2000 U.S. Census).

[3] Source: Wikipedia, “History of slavery in New York (state).” Accessed 6/17/21.

[4] “Neoliberal” means economically (and often socially) conservative.

[5] Source: Adapted from Klinkner & Smith (1999:328-45)

[6] Image credit: Creative Commons license (The original uploader was Captain Blood at English Wikipedia. – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons)

[7] Source: Quoted in Lewis & Diamond 2015:145.