Instructional Strategies and Engaging Pedagogies

4 Design Thinking for Creativity and Innovation at Schools

Zulikha Malekzai

Les Misérables

Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, the readers will be able to:

- Learn and understand the theoretical terms of Design Thinking as an innovative approach;

- Understand the importance of integrating a design thinking subject in the school curriculum for students of all ages;

- Learn the process and best practices for bringing design thinking initiatives to classrooms;

- Differentiate between a novice and an expert thinker;

Key Terms: Design Thinking, Design Thinking Process, Empathy, Prototype, Design Thinking Model,

Abstract: The twenty-first century has presented several obstacles to individuals in various fields, including education. Traditional tactics are frequently deemed ineffective in the new environment, necessitating the use of new tools and methodologies. An alternate technique that may be beneficial is the context provided by design thinking, which began in architecture, art, and design and is currently being used in many sectors. This chapter explores the foundation, processes, and teaching methods of design thinking for school students. The introduction and overview parts consist of important key points and literature to build the background for this chapter, followed by the DT process, which will be an essential part of the chapter. Through this chapter, readers will understand the value and importance of teaching DT to school students, especially in middle and high school.

figure 1: An infographic summary of the chapter.

Introduction; what is design thinking and how it works?

Design thinking (DT) is not an exclusive property of only designers, which gives it significant importance to any creator of art, literature, architecture, engineering, music, or business. DT helps schools develop critical thinkers, talented designers, competent communicators, and collaborators—generally, people who are interested in and involved in society (Luka, 2020). DT has been acknowledged as an essential approach to creating 21st-century competencies, and there has been a simultaneous surge in demand and interest in bringing design thinking to schools. (DT) operates as a machine to create innovative solutions for pragmatic issues.

The multi-dimensional characteristics of DT make it tough to have a specific definition, here some important ones have been cited: the foundation of interaction design, an educational organization dedicated to democratizing education, offering free educational resources, defines DT as “a non-linear, iterative process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions to prototype and test”. Brown (2008) defines it as a human-centred innovation method that draws on the designer’s toolset to connect people’s needs, technological possibilities, and business success factors.

DT integrates practice into academia. Take engineering as an example, according to Braha and Maimon (1997), engineering subject lacks an adequate scientific basis. Since the curriculum in this subject is strongly based on foundations and fundamental practices. Engineering students are considered by industry and academics to be unable to work practically in industries. This matter concerned professional engineers, leading them towards a more practical design process required for scientific community problem-solving. Furthermore, Razzouk and Shute (2012) offer a similar teaching concept for DT. The concept suggests that students should not be taught using non-interactive or unengaging methods or pedagogy in traditional content-focused learning systems. Assisting kids to design their thinking like designers would better equip them to deal with challenging situations and solve complicated problems inside the school or anywhere else.

Having excellent design thinking abilities can help students solve highly complicated challenges and adapt to unanticipated circumstances (Luka, 2020). The design process requires in-depth cognitive processes and also incorporates character and attitudinal attributes such as resilience and innovation (Bennett & Cassim, 2017). If schools are serious about training children to thrive and explore the world, they should not expect them to memorise and repeat things passively; instead, teachers can give them the chance to connect with knowledge, think critically, and use it to produce new understanding. Preparing students for future job settings necessitates teaching them how to use their thoughts effectively. Design thinking is an effective instructional technique based on the idea that students learn by addressing real-world issues. However, adopting this method in a classroom context is complicated (Rusmann & Ejsing-Duun, 2022). Schools must be careful of what methods they utilise to teach the students according to their age requirements.

Schools use design thinking to redesign school systems. When this method is applied to school systems, it encourages them to opt for an innovative mindset ready for change, which involves challenging the current beliefs and ideas about what school is or should be to effectively fulfil the needs of students. Another positive change that DT can bring to schools is that it changes the culture of work collaborations since teachers who adapt to DT will cultivate optimistic and action-oriented attitudes toward each other, which would make them change agents (Rusmann & Ejsing-Duun, 2022). Teachers start making models and doing experiments, which definitely change the traditional passive teaching methods. They also appreciate the need for rapid evolution with innovation and understand their crucial role in providing permissions and encouraging students to explore and create (Diefenthaler et al., 2017). The path of teaching students how to learn to design their thinking or represent their ideas in the form of prototypes or final products might vary for each student with different age limits or cognitive analysis.

OVERVIEW

Origins of Design thinking

In this section, we explore how design thinking evolved from a study of theory and practice into a successful approach to meeting modern humans’ technological and institutional needs.

The concept of design thinking started in architecture and design and was then adapted to management. The term has been used in academia for more than three decades, and it was originally related to the way designers think. Rowe originated the term “design thinking” in 1987 when he launched his book of the same title (Rowe, 1987). Despite some scholarly attempts in the 1960s such as Nigel Cross, the author of “A History of Design Methodology” (Cross, 1993), and Horst Rittel, the architect of the term “Wicked Problems” in the mid-60s (Rittel & Webber, 1973), Simon (1969) had previously studied the essence of design eighteen years before the term “Design Thinking” was coined. The book “the science of artificial” elaborated on the psychology of thinking, the science of design and creating artificial, highlighting Simon’s position on the origins of design thinking (Simon, 1969). The rationale for Design Thinking can also be seen in the ideologies of philosopher John Dewey who developed an epistemology of praxis that emphasized learning by interacting with things that addressed real-world problems rather than merely collecting decontextualized, subject-related data from textbooks and chalkboard lecturing. He was against schools being divided into classes that drill kids according to predetermined syllabi (Rusmann & Ejsing-Duun, 2022). The level of interaction and engagement in the school that Dewey proposed is visible in DT classes in terms of breaking the ideologies of students sitting in rows with some textbooks in hand to students coming together and providing real solutions to problems.

To search through the history of design thinking emergence in academics and practitioners, the roots of this phenomenon date back to years of world war two when engineers, business analysts, architects and scientists continued to struggle with the rapidly changing situations (Foster, 2021). The main purpose was to explore strategies and processes underlying innovation. The need for DT emerged when several companies found themselves unable to bring diversity to their products or respond to their client’s requirements.

Principles of Design Thinking “Commandments of Design Thinking”

When carrying out a Design Thinking class, the following principles must be followed:

- leave labels at the door!

During a Design Thinking session, there is no hierarchy of being a teacher or a student. - Embrace outlandish ideas!

Allow creativity to run free in your class. Any (insane) notion, and every concept, should be treated equally. - Quantity matters first!

Quantity comes before quality. Later, they will be chosen, studied, and assessed. - Utilize others’ ideas!

Copyright does not exist here. Others’ ideas should be adopted, enhanced, or modified freely. - Look at the human element!

People come first and foremost in Design Thinking or materials. - Make it visible and tactile!

Make use of drawings, sketches, pictures, movies, prototypes, and so on. - Stay away from criticism!

The production and assessment of ideas must be kept apart. - Fail fast and frequently!

Failure is synonymous with education. ‘Failure often means you’ve learnt a lot more than being successful. - Sustain your concentration!

Define your limitations and stick to the task assigned - Have some fun!

Creating new ideas in a group should be enjoyable. This is crucial for innovation (Mueller-Roterberg, 2018).

Why do schools Need Design Thinking?

Over the last decade, there has been an increase in incorporating design thinking into schools and most empirical pieces of evidence target middle school children with smaller units and short-term periods (Li & Zhan, 2022). Expert designers focus on solutions rather than problems. This appears to be a characteristic of design thinking that comes with education and design expertise. Regular assessment in a certain domain helps designers swiftly recognize a problem and provide a solution. The ability to generate, analyse, and evaluate a solution is commonly regarded as a crucial aspect of designing skills (Razzouk & Shute, 2012). This characteristic serves the purpose of this chapter which is to enable students to concentrate on solutions and start practising generating ideas for wicked problems from an early age. According to Razzouk & Shute (2012), to better equip students to tackle challenging situations and handle complicated problems during their school, job and life journey, schools teach DT helping students think like designers.

While delivering a DT course for school students, it’s important to aim for the competencies that students can apply and build during the design process, as well as how these competencies are portrayed in the literature. Li & Zhan’s (2022) in their research findings showed that although design thinking has significant pedagogical potential in K 12 education, empirical data supporting its usefulness is still limited. These researchers also note that DT can enhance students’ learning using diverse models in a variety of topic areas, covering STEM and non-STEM, with STEM applications being the most frequently stated in research studies.

Design Thinking models

Design thinking models shows the subsequent methodologies, procedures and process to allow for gathering reliable data analysing and predicting possible solutions (Irbīte & Strode, 2016).

- Linear Process: a process that begins with well-stated objectives and preconceptions about the expected outcomes. This process pursues a cycle consisting; of analysis, synthesis, development, and judgement.

- Dynamic Process: a process that begins with established objectives/tasks and yields partially predictable outcomes.

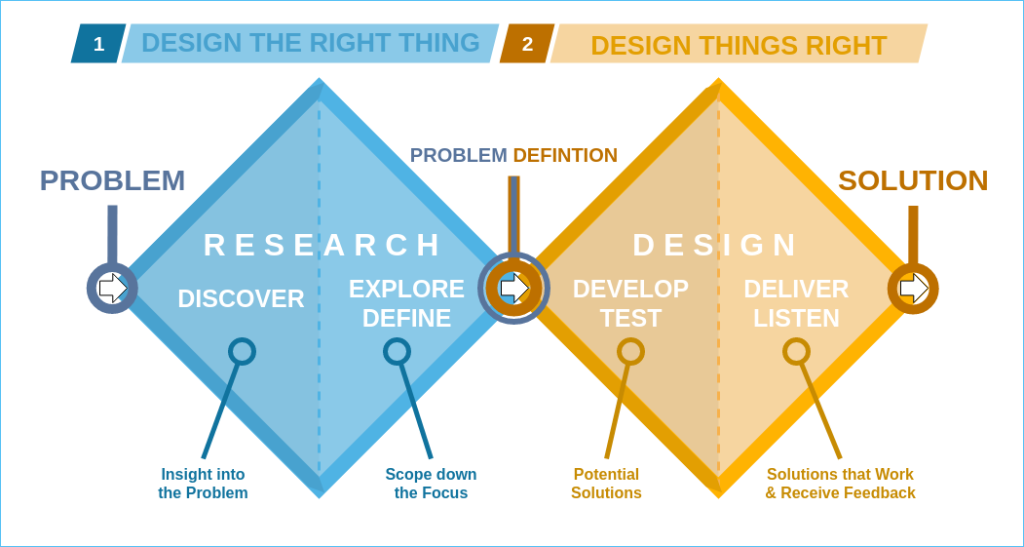

- Double Diamond design thinking model: a process of delving deeper into an issue and then taking targeted action. It is a somewhat or completely systematic procedure with specified goals/tasks and partially predictable outcomes same as a dynamic process.

Figure 2: an illustration of the Double Diamond design thinking process, (Digi-ark, n.d).

-

- Dynamic, Systemic, Upgoing process: A design approach that begins with no preconceptions about the possible outcomes. This model is required whenever a problem is identified, and modifications and improvements are necessary, however, it is unknown how to attain them. This process is mostly used when the problem we want to solve is complex and multidimensional. Moreover, it is usually used for social problems.

Although these models include a variety of techniques and methodologies, the authors believe it is hard to categorize them as contemporary or old (Irbīte & Strode, 2016). The need to utilise each model differ in terms of the nature of the wicked problem and the audiences.

Design Thinking Process

DT is a non-linear, creative process that, depending on whom you ask, may contain somewhere between three to seven phases. Although there is plenty of DT process suggested in different research articles (Waidelich et al., 2018), this chapter emphasizes the five-stage design thinking methodology provided by Hasso Plattner, Stanford’s Institute of Design (D.School Public Library) since it is globally known for how it teaches and applies design thinking.

- Empathize: Investigate your users’ needs to empathize,

- Define: express your users’ requirements and issues,

- Ideate: explore the assumptions and develop new ideas,

- Prototype: begin to develop solutions,

- Test: Experiment with your solutions,

Watching this simple summary of the design thinking process will give the reader a better idea before we dig deep into each process.

Figure 3. An informative video regarding the DT process (Sprouts, 2017).

-

Empathy: What is it?

For generating valuable and meaningful ideas and responses you must know your audience and care about their lives. As the first stage of DT, sympathy is a talent that enables us to realize and experience the same emotions as others (Alrubail, 2015). Empathy allows us to put ourselves in the shoes of another to understand how they feel regarding their problem. The Empathize mode is the effort you perform to understand people in the framework of your design issue. You attempt to grasp how and why they behave in a particular manner, their bodily and mental needs, how they perceive the world, and find out what is significant to them.

Why do we Empathize

What a design thinker does to find a solution is rarely related to their problem. This indicates that a design thinker always seeks possible ways to solve other people’s problems, therefore, learning empathy and people’s priorities is a must. What individuals do and the way they interact with their surroundings reveal significant information as to what they believe and feel regarding a certain matter. Besides understanding their requirements, a design thinker may also record tangible expressions of people’s experiences by watching them. The insights that a design thinker gains from observing the audience can ease the idea-creation process to a massive extent (Platter, 2009). A direct clear conversation can even reveal the values that a person holds and is not aware of. If a designer can cultivate empathy, he or she can transform even the most difficult scenario into a delightful situation for the consumers.

How to Empathize

Now that the term empathy is clear it’s vital to know the best way to empathize with the end-users. Here are some essential tools to empathize:

- Observe: Consider users and their actions considering their lives. Interviews are not enough, do observations in relevant circumstances as often as feasible. Observing a critical gap between what is being said with what is done leads to the most striking realizations and too valuable information in the design process.

- Engage: – This approach is sometimes referred to as “interviewing,” although it should seem more like a discussion. Prepare some questions that you’ll ask, but be prepared for the conversation to divert beyond or around them. Keep the discussion as open as possible. Ask about their experiences, stories, and actions. Besides, constantly ask “Why?” during the talk to extract much deeper meaning.

- Pay attention and listen. Observation and engagement may and should be combined. ask the person to demonstrate how they do a task. Allow them to walk you through stages and explain why and how they do them. Request them to verbally express what passes their minds when they complete that task or engage with an artefact. Have the discussion in their home or office – objects contain so many memories. Use the surroundings to elicit more in-depth questions.

Pay attention to each important data that have been gathered, writing them down is essential to extract useful information for the next process.

2. Define

In this stage, design thinkers define the taken information to define the primary problem that needs to be fixed. Students must utilize language that is recognizable, positive, relevant, and practical throughout this process. Instead of emphasizing the unpleasant and negative aspects of the situation and the lack of solutions, encourage pupils to use positive, sympathetic language that will lead students to a solution-based approach. Essentially in this stage, the designer brings clarity to his thoughts with the help of gathered information, which can be completely useless if not used to create a greater picture of the problem (Dam & Siang, 2019). Defining is not easy as the answer would not pop up from your data, this process needs thorough analysing of the data, finding connections and patterns leading to a significant problem.

– D.school, Bootcamp Bootleg

Analyze and Synthesize

It is critical to understand the connection and difference between analysis and synthesis that many design thinkers encounter in their projects. The president of IDEO, the Innovation Design Engineering Organization, Tim Brown talks about the importance of the relationship between the two stages as; “equally important, and each plays an essential role in the process of creating options and making choices” (Dam & Siang, 2019a). Analysis is the process of breaking down complicated problems and issues into smaller, more understandable elements. this process is done during the Empathies stage when we notice and capture main pieces of information related to our end-users. Synthesis, on the contrary, entails creatively fitting together the pieces to produce an entire concept and a point of view. This occurs at the Define step, when we organize, interpret, and create meaning from the evidence we collected to formulate a problem statement. The analysis part includes four categories of information (CloudApp, 2019):

- What has been said by the user,

- What has been done; the behaviour and actions,

- Thoughts; what users think in light of their beliefs, motivations, ambitions, needs, and wants,

- What they have felt, feelings emotions,

While defining concrete points of view are extracted as a problem statement to enter the next stage of the process with clear minds.

3. Ideate

In this stage the goal is not about coming up with the “perfect” concept; it’s about producing plenty of ideas and various options. During ideation, the designer focuses on idea creation. It depicts a mental process of “going broad” in terms of thoughts and results. Ideation serves as both the fuel and the raw material for prototyping and delivering creative solutions.

Why Ideate?

- Bring Innovation by asking the correct questions,

- Step outside of the typical answers to improve the innovative capacity of your idea,

- Bring together group members’ ideas and expertise,

- Discover new areas of creativity,

- Increase the quantity and variety of your innovation alternatives,

- Remove apparent answers from your mind and push your team beyond them (Dam & Siang, 2019b).

How to Ideate?

You come up with ideas by integrating your conscious and unconscious minds, as well as your reasonable and imaginative thinking. The building is another ideation strategy; in fact, prototyping may be an ideation technique. Making something physically forces you to make decisions, which enables new ideas to emerge (D.School, 2004). Several tools can be used to do the process such as brainstorming, brainwriting, mind mapping, sketching, storyboarding and a lot more (Dam & Siang, 2019b). However, the crucial part is to facilitate the process effectively to get the maximum number of ideas.

Ideation is a productive and intense procedure; individuals participating should be given an environment that allows for the free, open, and non-judgmental exchange of ideas. People require direction, motivation, and tasks to get the process started. To transition to the next phase and prevent losing most of the innovation potential the design thinker has just developed throughout the ideation process, Plattner (2004) suggests a process of deliberate selection, in which the designer carry many ideas ahead into prototyping, therefore keeping the innovation potential high.

4. PROTOTYPE

The Prototypes are used to generate artefacts iteratively in order to answer problems that bring you closer to your ultimate solution. In the early phases of a project, the question might be broad in that you can design minimal prototypes that are simple and inexpensive to create (needs minutes and little money). According to the D. School (2004), students can get valuable reactions and feedback from their team and consumers even at the early stages of prototyping. After the first round, your problem statement and prototype may get much clearer and more achievable.

Prototypes are frequently utilized in the final stage of the testing step to identify how people interact with the prototype, uncover new and better solutions, or assess effectively the prototype. Building prototypes is the rational approach in which the designer creates a low-profile version of the end product for the users to test since it would be an unwise and costly idea to finalize a product and then send them for the experimentation stage to be tested by the users (Dam & Siang, 2020). A prototype is the best way to fail fast and inexpensively so that the designer can receive feedback and return to the previous stages as needed.

How to Prototype:

- Get to work and start constructing your prototype as early as possible. Only the act of taking materials and working with them brings more ideas to the surface.

- You don’t need to spend all your time on the prototype. The more swiftly you build your prototypes the sooner you receive your feedback and can start another one. Getting attached to one prototype hinders you from looking at other aspects.

- Keep the question in mind; each prototype should be built in response to a problem or question.

- Keep the end user in your mind, since they would be testing the product. It depends on what emotion and reaction the designer wants to see while testing.

5. TEST

This is where you gather feedback from your users on the prototypes you’ve made and acquire more empathy for the people you are designing for. This is the best chance to empathize with your end-users from a better aspect. The testing mode should only contain questions like whether they like or enjoy the product or not instead dig deep and ask what they feel and why they are enjoying or either not comfortable with the product. The reason that makes testing is essential is that this phase refines the prototype (D. School, 2004). Furthermore, the problem statement or the designers’ points of view gets clearer.

How to test?

-

- The prototype must be shown not explained! In this stage it is better to put your product in the hands of your user or an experienced person then watch and listen to them. You can watch and record their interaction and see how they use or misuse it,

- The users are here to interact with the product not to evaluate it. The testing mode needs to be an experiencing stage not an assessment from the user’s side,

- Request the users to compare. Bringing many prototypes to the field for testing allows people to compare them, and comparisons frequently uncover latent needs.

Debate

Waidelich with friends (2018), has done a thorough review of the DT process and evaluated more than 30 processes, the findings show clear similarities and distinct differences between the process models. Some essentials are highlighted below:

Similarities: in most of the process models the term “Ideate” appears most repeatedly. Which demonstrates the importance of this element in a DT process model. In ideation, ideas are developed to provide an appropriate answer to the question. Besides, the “Prototype” phase is also common in the majority of the models. The ideas generated during the ideation process can be prototyped in many ways to picture a potential solution.

Differences: the main difference points among the process models is that the majority of the models start with an “Understanding” phase while many start their model by directly defining the problem which indicates the inconsistency between the states. Further Waidelich and friends have explored that there’s a second observation concern in the lifespan of the identified models. A few of the models wrap up the process with a “Testing/Test” while some ends the process with the “Implementation” phase and ignore the assessing or testing of the process at the end.

DIFFERENCES between novice and Expert thinker

Generally, a skilled designer should be able to apply many problem-solving methodologies and select one that best matches the needs of the context (Razzouk & Shute, 2012). Nigel (2004) connects novice action with a low surface-depth method of problem-solving, that is, discovering and examining alternative solutions for problems in a progressive way. Expert techniques are commonly viewed as mainly top-down, comprehensive approaches. The expert designer employs specific problem-decomposing methodologies that a beginner designer lack. Experts are reported to be capable of retaining and accessing knowledge in bigger cognitive chunks than novices, as well as understanding fundamental concepts instead of focusing on superficial aspects of the issue (Günther & Ehrlenspiel, 1999). As a result, gaining experience and continued practice is crucial in the transition from novice to expert.

Expert designers look for solutions rather than problems. This characteristic of design thinking emerges from knowledge and expertise (Cross, 2004). Building experience in a certain domain, for example, helps designers swiftly recognize a problem and provide a solution. The ability to generate, synthesize, and evaluate a solution is commonly regarded as a crucial aspect of design skills.

Characteristics of Design Thinking

- Ambiguity: Feeling at ease when things are confusing or you don’t understand the solution,

- Collaboration: Collaborating across fields,

- Constructive: Developing new ideas from old ones, which may also be the most effective ideas,

- Inquisitiveness: A curiosity in things you don’t grasp or seeing things through new eyes,

- Empathy is the capacity to see and comprehend things through the eyes of your consumers,

- Holistic: Considering the bigger picture for the consumer,

- Iterative: A circular process in which improvements to a solution or concept are produced regardless of the stage,

- Non-judgmental: Developing ideas without reference to the author or the notion,

- Open mindset: Accepting design thinking as a solution to any challenge, irrespective of the industry or scope.

Characteristics of Design Thinker

There are some attributes and characteristics which are common among the design thinkers, such as:

- Emphasis on individual interests and needs. Empathize with them, ask for their feedback, and incorporate it into their designs,

- Integrate experiments into the design process, be active “problem solvers,” and communicate effectively

Interact with individuals from varied backgrounds and respects their opinions; enable “bold new thoughts and ideas raised from each individual”, - make sure to bring clarity to complex situations,

- Can cope with difficult situations, are inquiring and positive, and are holistic thinkers who consider the user’s broader context,

- Are aware of the whole Design Thinking procedure in terms of goals, objectives and methodologies.

The Foil Challenge: Create a dining utensil

Prerequisites:

- Audience: 3rd graders and above.

- Why: to bring a broad outline of an issue of design thinking and practice to create a tool for resolving the issue (here using an aluminium foil)

- Numbers of students: at least two students with a teacher or the whole class.

- How to do it? Students do pair interviews regarding their favourite cuisines and They then construct a gadget for eating this meal out of a square of metal.

- required materials: aluminium, note paper, pen/pencil

Duration:

- Students can take 10 minutes for interviewing each other

- for 2 minutes they spend a certain amount of time visualising a prototype of a unique eating tool for their partner depending on their favourite dish. During this time, they should avoid interacting.

- then the teacher gives them the tin foils and notifies them that a prototype can be anything they can make of that foil for their partner.

- In 4 minutes, they show their designs to their partners.

- for another 4 minutes, the teacher can show the designs to the whole class and discuss them with them

- last 10 minutes they can discuss the situation as a group or by dividing individuals into foursomes. They can talk about their interview experiences and how they got their designs’ insights [1].

How to teach effectively

Finally, improving students’ design thinking abilities may be accomplished by introducing authentic and interesting activities into the classroom and offering numerous opportunities to apply design processes. As students complete the assignments, evidence is gathered to assess their performance. Such data can help instructors monitor student performance, determine current weaknesses and strengths about the characteristics, and provide focused feedback to enhance student performance (Razzouk & Shute, 2012). Teachers may introduce students to different simple materials and give them wider space to think freely and generate many ideas for one problem. The objective of educators should not be to prepare children to score well on general or standardized tests, but to provide them with robust skill sets that will help them flourish both inside and outside of the classroom. They can utilise some basic yet cost-effective tools to make their prototypes and stay open-minded to observing any possible solution.

Expert Corner

Dr. Stefanie Panke is a professor of educational technology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. She is a native German speaker with a PhD in Applied Linguistics and Literature from the University of Bielefeld, which she earned with honours in 2012. Social media, informal learning, open educational materials, and design thinking are among her research interests.

Read more: https://panke.web.unc.edu/

“It’s okay if something does not work, as long as you learn from it”

(Dr. Stephanie Panke)

What is the best time to learn Design Thinking?

“Learning and teaching DT highly depends on the age group, the teaching can happen either for the pre-school kids or for secondary or high school students.

-

- for pre-school kids, since they cannot read and write properly, a lot of the teaching must be playful around songs, stories and crafts and it also has to be around adventures and quests. Since DT provides that playful facilitation process, its often fast paced with clear rules in the process and it can be done at a fairly young age for kids.

- On the other side, the student can be of high school grades with a wide range of ages, from privileged or maybe disenfranchised backgrounds, they are a fair audience for this subject. It is the mindset of the teacher that matters to allow himself to walk through the classroom door and start teaching a group of young students that might lough at him/her. Students from higher grades may catch and learn the process much easier however, the important part for a teacher is to visualise the target and know what are they going for till the end of the process.”

Conclusion

This chapter presented some fundamental theories, teaching methodologies and practices of design thinking stressing the need for this subject in the school curriculum. The term combines academics with theory in search of suitable solutions for potential real problems. Equipped with these skills are innovative and lively enough to tackle challenges by bringing up ideas, creativity and a positive attitude. This chapter clears the path for unprivileged schools and communities to open up the door of innovation in school students that one day might solve huge community issues. DT technique is used to provide an actual example of developed items such as the incredible success narrative of Apple being the most prominent globally recognized brand in 2017 with design thinking (Waidelich et al., 2018). The non-linear process of design thinking and the number of times it can refine the process to create an optimum solution makes it a great tool for students to learn resistance, patience and cooperation. The process teaches them to learn from mistakes easily and learn it fast to repair the damage.

Teaching this subject might be a troublesome for a new teacher since each exercise must be practiced and confirmed before getting applied to the class with students. Students on the other hand might get frustrated and irritated with unwanted results and loose motivation which again requires the teacher to get the things on track and start over again. As illustrated in the infographic, there are plenty of online games, websites and mobile apps that can help teachers along with teaching the students, however, the teacher needs to use the online tools first before introducing to the class. Training creative novice designers from school grades may require a lot more struggle than training adults, nevertheless, it is an effort worth trying for a bright and reformed future for the next generations.

Review Questions

There are few questions intriguing to the mind that might help you want to research more on the topic:

- Does the design thinker’s sentiments and emotions have any influence on the DT process? If so, is it positive or negative?

- What part of the Design Thinking process seems difficult to accomplish?

- Are school students, good audiences for this course? Why?

- What are the difficulties of teaching DT for school students? How to overcome them?

Recommended Readings

The below readings may add more value to your knowledge of the Design Thinking concept:

- Müller-Roterberg, Christian. (2018). Handbook of Design Thinking. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329310644_Handbook_of_Design_Thinking

- Henriksen, D., & Richardson, C. (2017). Teachers are designers: Addressing problems of practice in education. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(2), 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717734192 ( This article is a gift for teachers who want to become design thinkers for their students)

Zotero Reference group

https://www.zotero.org/groups/4854282/design_thinking_for_class_creativity_and_innovation

Reference

Alrubail, R. (2015, June 2). Teaching Empathy Through Design Thinking. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/teaching-empathy-through-design-thinking-rusul-alrubail

Bennett, A. G., & Cassim, F. (2017). How Design Education Can Use Generative Play to Innovate for Social Change: A Case Study on the Design of South African Children’s Health Education Toolkits. 11(2).

Braha, D., & Maimon, O. (1997). The design process: Properties, paradigms, and structure. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics – Part A: Systems and Humans, 27(2), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1109/3468.554679

Brown, T. (2008). Design Thinking. Harvard Business Reveiw, 86(8), 84.

CloudApp. (2019, August 15). Design Thinking Define Stage: Identify Your Users’ Core Challenge. CloudApp. https://www.getcloudapp.com/blog/marketing/design-thinking-define-stage/

Cross, N. (1993). A History of Design Methodology. In M. J. Vries, N. Cross, & D. P. Grant (Eds.), Design Methodology and Relationships with Science (pp. 15–27). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8220-9_2

Dam, R. F., & Siang, T. Y. (2019a). Stage 2 in the Design Thinking Process: Define the Problem and Interpret the Results. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/stage-2-in-the-design-thinking-process-define-the-problem-and-interpret-the-results

Dam, R. F., & Siang, T. Y. (2019b). Stage 3 in the Design Thinking Process: Ideate. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/stage-3-in-the-design-thinking-process-ideate

Dam, R. F., & Siang, T. Y. (2020). Stage 4 in the Design Thinking Process: Prototype. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/stage-4-in-the-design-thinking-process-prototype

Diefenthaler, A., Moorhead, L., Speicher, S., Bear, C., & Cerminaro, D. (2017). Thinking & Acting Like a Designer: How design thinking supports innovation in K-12 education. World Innovation Summit for Education.

Digi-ark, (n.d), Double Diamond design thinking process, Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=94113884

D.School. (2004). An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE. Institute of Design at Stanford.

D.school Public Library. (n.d.). Stanford d.School. Retrieved 9 January 2023, from https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/public-library

Foster, M. K. (2021). Design Thinking: A Creative Approach to Problem Solving. Management Teaching Review, 6(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298119871468

Günther, J., & Ehrlenspiel, K. (1999). Comparing designers from practice and designers with systematic design education , 20, 439-451. Design Studies, 20, 439–451.

Henriksen, D., & Richardson, C. (2017). Teachers are designers: Addressing problems of practice in education. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(2), 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717734192

Irbīte, A., & Strode, A. (2016). DESIGN THINKING MODELS IN DESIGN RESEARCH AND EDUCATION. SOCIETY. INTEGRATION. EDUCATION. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, 4, 488. https://doi.org/10.17770/sie2016vol4.1584

Li, T., & Zhan, Z. (2022). A Systematic Review on Design Thinking Integrated Learning in K-12 Education. Applied Sciences, 12(16), 8077. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168077

Luka, I. (2020). Design Thinking in Pedagogy. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 5(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20142.63.74

Razzouk, R., & Shute, V. (2012). What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important? Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 330–348. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312457429

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Rowe, P. G. (1987). Design Thinking. Caambridge MA: MIT press.

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

Sprouts, (2017). The Design Thinking Process, YouTube. Accessed from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r0VX-aU_T8&t=5s

Waidelich, L., Richter, A., Kolmel, B., & Bulander, R. (2018). Design Thinking Process Model Review. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICE.2018.8436281

Waloszek, G. (2012, September 12). Introduction to Design Thinking | SAP Blogs. https://blogs.sap.com/2012/09/12/introduction-to-design-thinking/

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57c6b79629687fde090a0fdd/t/58ac88a429687fbaf4a81d09/1487702181436/FoilChallenge.pdf ↵

a problem-solving strategy based on solutions.

" Design process is the way in which methods come together through a series of actions, events or steps" (Waloszek, 2012).

Empathy is the skill gained by designers via research to completely understand people' issues, requirements, and goals in order to build the best solutions for them.

a first or experimental version of a device or a product from which subsequent versions are produced.

The different approaches that some design focussed agencies has provided as the Design Thinking process: such D.School, IDEO, AC3D model...etc.