Chapter 9: Conclusion

Helga Hambrock

9.1 Introduction

To conduct an international study with 13 researchers from 10 countries in four continents with six different time zones and only two being English first language speakers, can be rather daunting. However, with a team of researchers who share the same vision to improve education globally for the greater good, this research study became a reality.

The timeline had to be adjusted regularly as many challenges came our way due to the pandemic in which some researchers became sick, some landed in hospital, and others worked through the loss of loved ones. Additional challenges included changes in lifestyle because of lockdowns. One researcher mentioned having to move their whole family from one part of the country to another. Despite all these challenging experiences, the research has arrived at the final stage of combining all the findings in this chapter.

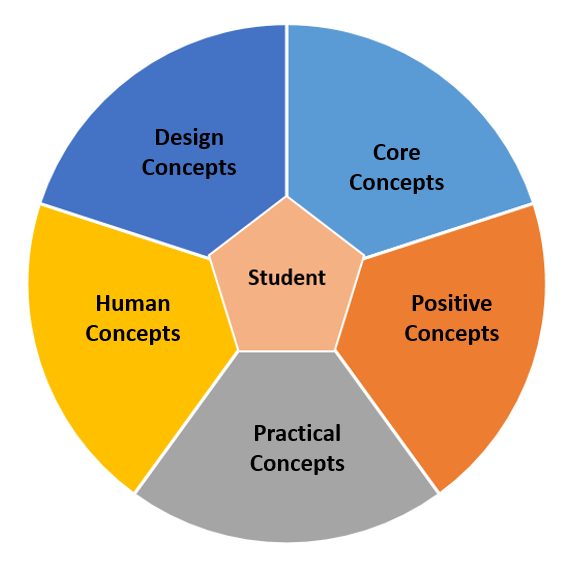

The main research question of this study is “How prepared are higher education institutions for seamless learning internationally?” In order to come to a conclusion and to establish an answer to this question, the participants of the study completed a survey with questions based on the five concepts of the seamless learning experience design (SLED) model (Hambrock & De Villiers, 2022) portrayed in Figure 9.1.

Each concept is an umbrella for a number of sub-concepts, which in turn include a number of sub-criteria in the survey. The data collected from the survey were then combined and analyzed methodically, concept by concept. The meanings of the concepts are discussed in detail in the relevant chapters. They are distributed as follows in this book: the seamless learning concept (Chapter 2), the positive concept (Chapter 3), the practical concepts (Chapter 4), the human concepts (Chapter 5) and the design concepts (Chapter 6).

Figure 9.1

Seamless learning experience design (SLED) model (Hambrock & De Villiers, 2022)

The criteria are used to analyze courses at each of the respective universities in the respective countries by a respective researcher. The next step for the researchers was to work collaboratively; two or three researchers worked together on each chapter. Each researcher selected several sub-concepts in their respective chapter and explained them based on extant literature and their relevance to this study. As indicated in the table below (Table 9.1), each concept included six to nine sub-concepts as well as 117 criteria. The total number of criteria adds up to 153.

Table 9.1

Seamless learning concepts

| Concepts | Core Learning Concepts | Positive | Practical | Human | Design | (n=) |

| Sub-concepts | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 36 |

| Criteria | 57 | 22 | 23 | 19 | 22 | 117 |

| Total | 77 | 29 | 32 | 26 | 28 | 153 |

The sub-concepts and the criteria (as explained above) are counted per identified course to establish if the courses are seamless learning ready or need attention. A description of these concepts is presented in section 9.2.

9.2 Summary of Concepts

A short summary of the concepts and the sub-concepts is included below:

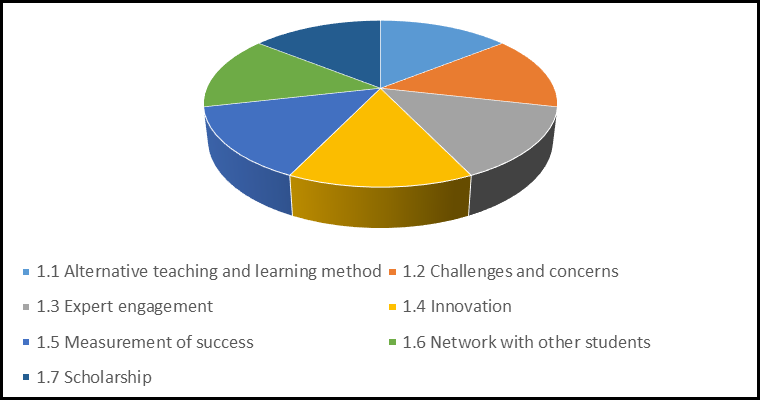

Figure 9.2

Seamless learning concepts

9.2.1 Core Concepts of Seamless Learning

The sub-concepts that are included under the core seamless learning concepts refer to various aspects that can take learning from a mediocre, uninspiring learning experience to a quality learning experience available at any time without major interruptions.

9.2.1.1 Alternative Teaching and Learning Methods

The main idea of a seamless learning pedagogy is that the students are encouraged to take responsibility for their learning. The aim would be to achieve “a process by which individuals take the initiative, with or without the assistance of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, and evaluating learning outcomes” (Knowles, 1975, p.18)

9.2.1.2 Challenges and Concerns

Challenges include access to and affordability of technical resources as well as training on how to use these tools, and having limited access to peer engagement. Markowitz (2020) notes that engagement with peers is vital because “students learn more effectively through interaction, collaboration, and discussion with other students than they do through individual study.”

9.2.1.3 Expert Engagement

Learning from experts and experiential learning needs to be available so the students can learn from those most knowledgeable and skilled and so the students can be exposed to the world of work.

9.2.1.4. Innovation

Innovative teaching and learning offers students an opportunity to think out of the box and to introduce authentic learning practices through techniques and technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality, and game based learning.

9.2.1.5 Measurement of Success

Another important aspect is the measurement and assessment of success. Authentic application of the knowledge in a real-world scenario seems to be a highly efficient and relevant mode of assessment. In addition, it may be argued that it also combats cheating by requiring the student to actively demonstrate their knowledge and skills in vivo. No less important is the provision of summative feedback to students which can also be directed towards improving the quality of their learning.

9.2.1.6 Network with Other Students

Networking with other students can be found in social learning, collaborative learning, and learning through social constructivism. Mateev and Milter (2010) suggest that group-based learning (where students interact and network with one another) is advantageous to learners in the sense that it develops analytical skills and enhances “ownership of learning and reflective practice.” It may also increase student satisfaction, higher-order thinking, and long-term retention (Pombo et al., 2010).

9.2.1.7 Scholarship

Scholarship refers to issues regarding the culture and ethics around teaching and learning in the classroom. It also includes commitment to research beyond the classroom.

Figure 9.3

Positive concepts

9.2.2 Positive Concepts

The positive concepts category supports the quest to improve access for students to quality learning at anytime and anywhere—including fostering global awareness and global interaction, with the student as the center of the learning experience.

9.2.2.1 Student-Centered Design

This sub concept is also mentioned as part of the first, seamless learning concept, whilst here, it refers to the student taking part in the positive concepts of the learning process from a psychological perspective. According to Alessi and Trollip, (2001), students should have opportunities to design their own knowledge and skills. This exercise would not only improve the students research and knowledge curation skills but can also have positive effects upon students’ feeling of accomplishment and self-confidence. This sub-concept also includes student-specific needs such as disabilities, learning preferences, self-regulation, critical thinking, reflections, reasoning as well as achievement of performance goals.

9.2.2.2 Globalization

Among all the advances in mobility, globalization is perhaps the most important. Globalization has led to the adaptation of learning policies globally. Anderson (1997) and Altun (2017) describe global education as a means to improve human and global citizenship while having a significant impact on the social citizenship content of education. As stated by the United Nations; “The primary aim of Global Citizenship Education (GCED) is nurturing respect for all, building a sense of belonging to a common humanity and helping learners become responsible and active global citizens” (United Nations, 2022a).

Thus, including a global citizen education approach contributes to the positive concepts for a seamless learning experience as it opens the thinking of the students beyond their own limited world view by partaking in a learning experience beyond regional and political boundaries. This globalized learning experience can be offered in the form of global collaboration projects to address similar problems like global warning and education.

9.2.2.3 Practical Experience

Practical experience is also mentioned as part of the seamless learning concept. Whilst it focused on the pedagogical approach of learning by doing (a constructivist learning approach), practical experience in this context can facilitate the ability to work online and learn in the field simultaneously. This means that the student is learning how to use the technology, and, at the same time, the student can observe how theory is applied in practice. Hands-on experience can provide insights and be a motivational experience for the student.

9.2.2.4 Preparation for the Future

This preparation for the future concept is used in both the seamless learning category and the positive concepts category. Students can learn from books but can learn more in practice as preparation for the world of work as well as preparation for social, political, domestic, and cultural life more generally. Students need to know about the world around them even before they leave the “safe walls” of higher education institutions (Box, 2005).

9.2.2.5 Real-Time Interaction

Positive interaction between students, instructors, and peers can be continued beyond the face-to-face. Immediate feedback needs to be provided to the student by the instructor or vice versa (Van der Kleij, 2008). Feedback from the instructor helps the student understand their level of performance and/or knowledge. Feedback from the student helps an instructor better understand the needs of the student. In a seamless learning environment, feedback can be pursued before, after, and during class with the aid of mobile/online.

9.2.2.6 Remote Access

The positive concept, remote learning, suggests that students can have access to learning even if they are not on campus. Even if there are no time or space barriers, the learning needs to be planned well to overcome access and affordability challenges.

9.2.2.7 Research Opportunities

Seamless learning also opens the opportunity for students to increase and improve their research output. Increased output can be achieved by ensuring access to resources, increased contacts, and growth of networks via social media. It also offers more opportunities in terms of conferences being more affordable as they can move online.

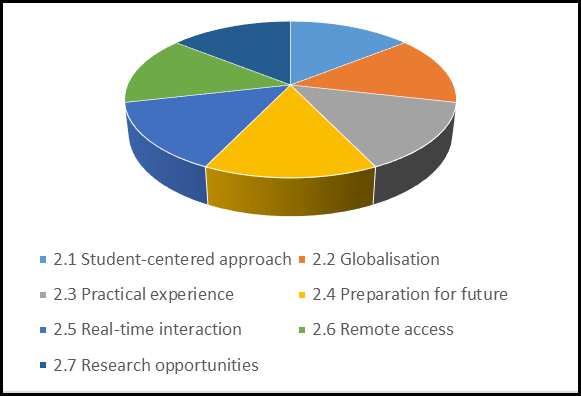

Figure 9.4

Practical concepts

9.2.3 Practical Concepts

The sub-concepts include tools, devices, and services that are important to achieve a seamless learning experience. If any of these are unavailable or inaccessible, the level of quality of an educational experience will likely decrease.

9.2.3.1 Data

Data is needed for students who lack access to WiFi connections. Remote campuses sometimes lack adequate connections to the Internet and data is often necessary for the students to access their learning material.

9.2.3.2 Devices

Devices and hardware refer to mobile and stationary devices such as laptops, smartphones and PC computers. For students who lack the financial means to acquire devices, it can be a significant challenge to access any information available only online. Every student needs, at least, access to a computer lab or access to a rental device.

9.2.3.3 Funding and Cost

Funding and cost need to be considered in student, instructor, institutional budgets to cover technology acquisition and maintenance costs. Technology evolves at a very high pace, and tertiary educational institutions must keep pace. If institutions neglect planning and budgeting for license renewals and hardware evergreening, another important avenue of access to knowledge will be impacted negatively.

9.2.3.4 Infrastructure

Infrastructure includes electricity, internet, servers, classrooms, and computer rooms as well as libraries and workspaces on campus. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became even clearer than before that Universities need to be prepared for both on campus and off campus teaching. The infrastructure on campus must be in place even if students can work off campus. Consistent and robust technological infrastructure to enable collaborative work and direct-contact classes. Practical application classes such as art, music, theatre, engineering and medical courses are particularly impacted by the quality of infrastructure on campus.

9.2.3.5 WiFi

WiFi is a type of radio signal that is transmitted between a device and an internet router to provide connectivity for computers, tablets, smartphones, and other devices. It provides internet connections via a university or corporately-controlled internet-service provider (ISP) allowing students to access their online content and to do research.

9.2.3.6 Policies

Policies to address practical concepts need to be in place for institutions so instructors, administrators, and students know the expectations and follow guidelines. These policies need to be carefully considered by management and stakeholders through collegial processes so they can capture and address their respective needs.

9.2.3.7 Software

Software includes the programs that need to be uploaded on the devices to be used by the students, instructors, administrators, and the university-wide community. These can be acquired by purchasing licenses or they can be bought as new programmes. In education, there is a great variety of software systems and platforms that are required including but not limited to: learning management systems, relationship management systems, student information systems, project management software, office management software programs, and financial management systems.

9.2.3.8 Support

Support needs to be available in the form of a helpdesk that offers assistance to students, instructors, and all workers at the university in case of power failures, systems and device failures, technical challenges to name but a few. A 24-hour service is important—particularly for remote or blended learning—as the most unexpected challenges can occur at the most unexpected times and can create major concerns and anxiety.

9.2.3.9 Technology

Technology should be available and should be maintained or replaced regularly. Besides devices as discussed in 9.2.3.2, technology also includes servers on campus and VPN connections for working off campus. Updating and replacing deprecated systems is central for virus protection and cyber-security. Instructors in tertiary education environments require ongoing technical training and upskilling as well as technical support to keep track of system changes and to be prepared in case of emergencies.

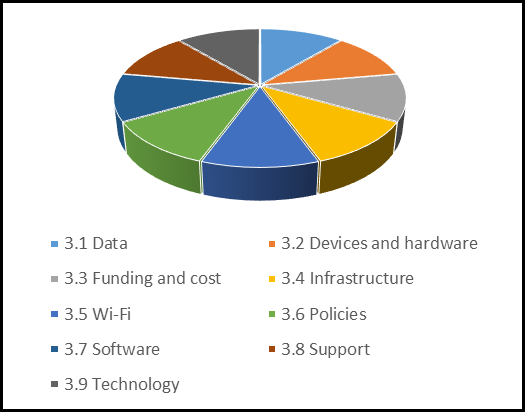

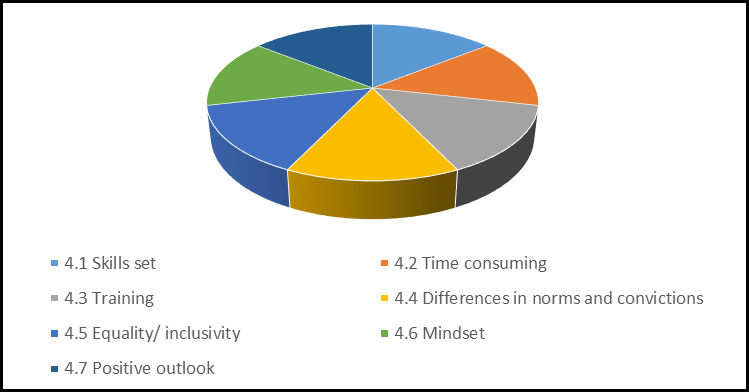

Figure 9.5

Human Concepts

9.2.4 Human Concepts

These concepts focus on the ability and approach of the human factor (i.e., people) when it comes to seamless learning.

9.2.4.1 Skills Set

All who use a seamless learning approach need to understand the skills needed. Skill set include knowledge on how to use technology and how to apply it for research, writing, and creating assignments, and class interaction.

9.2.4.2 Time

The phrase, time consuming, refers to the time needed to learn concepts and technology for seamless learning. Many instructors, who are constantly balancing research, teaching, and service to their institutions, feel that they lack the time to learn additional skills and technologies. This is an enormous barrier for many and asking them to adopt the seamless learning approach is yet another complication to their responsibilities.

9.2.4.3 Training

Training is where the secret of improvement of skills and attitude lies. During training sessions, whether one-on-one or in groups, the instructors and students come to know shortcuts and paths to achieve a successful seamless learning approach more quickly and efficiently.

9.2.4.4 Differences in Norms and Convictions

Differences in norms and convictions touch upon the sense of ethics of the students. Encouraging learners to be honest and to live a responsible life is a valuable endeavour. With a solid understanding of academic integrity, students, will hopefully, strive for excellence and complete assignments without plagiarizing work from others. Appreciating the authenticity of their own work, students feel be proud of their achievements.

9.2.4.5 Equality/Inclusivity

Equality and inclusivity suggests that all students should have equal access to education. Measures need to be in place to ensure that anyone who wishes to study can do so regardless of their financial standing, whether they belong to a particular age, racial, or social class, or whether they are differently abled. This needs to be a non-negotiable part of any university and represents a basic human right.

9.2.4.6 Mindset

Mindset can be located anywhere along a continuum of negative or positive. Students can come to a university with a positive mindset wanting to learn and grow, or they can arrive with insecurities, deficit thinking, and a sense of self-entitlement. Students’ attitudes can also change during their learning journey; they can be influenced by fellow students to become negative and develop detrimental attitudes and behaviours that interfere with their learning. Although the learners are in control of their behaviours, it is important to consider how the culture at a university can affect the mindset of a student.

9.2.4.7 Positive Outlook

Positive outlooks is intertwined with a positive mindset (as above in 4.6). If a student is negative towards studying, they can be assured that their result will be similarly affected. An outlook can change if the student can see the relevance of the topic, is stimulated by interaction with those around them, and receives timely feedback from the instructor—to name a few factors.

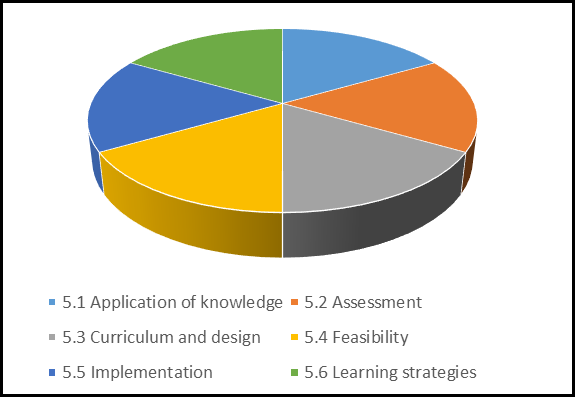

Figure 9.6

Design Concepts

9.2.5 Design Concepts

Another important concept under the seamless learning umbrella is design. Effective design is predicated upon a good understanding of the tasks/knowledge to be learned, an understanding of the needs and characteristics of the learners, how and in what sequence information is presented, how learning strategies are selected, and how the learner is assessed.

9.2.5.1 Application of Knowledge

Within the content and design of a seamless learning experience the student needs to be able and confident to apply the knowledge following instruction. Assignments need to be designed so students can apply their newly acquired knowledge.

9.2.5.2 Assessment

Testing and checking student knowledge is an important part of all education systems. Within the seamless learning approach assessments need to be presented appropriately with consideration given to the topic, the learners’ levels and characteristics, the context, and the available resources. Decisions need to be made regarding whether to use a continuous or segmented approach during the term, whether to use reflection and application papers, whether the use of case studies or real-world scenarios. If the case studies include highly contextualized and authentic assignments, students will be less able to copy others’ assignments.

9.2.5.3 Curriculum and Design

Curriculum and design are the backbone of a seamless learning experience. The curriculum focuses on the content and the design on how the content is presented and researched by the student. For example, using a problem-based learning approach, the students can identify a problem of interest to them. Then, they can brainstorm collaboratively to explore possible approaches, and/or do research and experiments to find the best solution. The learning activity and approach needs to be carefully considered and appropriately support the tasks and knowledge to be learned.

9.2.5.4 Feasibility

A design must be feasible. The tasks and outcomes must be achievable. The necessary resources must be available. The formatting and presentation should be professional and content accurate. Instructors should be available and knowledgeable enough to lead the course. The course needs to be quality checked by the leadership before students are enrolled in the course.

9.2.5.5 Implementation

The successful implementation of a course relies 1) all feasibility checks being completed, and 2) on the feedback of the students following piloting. The suggestions of the students can be implemented to improve the quality of the course, method, and content.

9.2.5.6 Learning Strategies

Learning strategies include presenting the content to the student via a selected learning methodology and modality. If possible, it is helpful to first assess the knowledge of the learners and then match the content (appropriate level), methodology (direct instruction, self-directed learning, etc.), and design of the course (linear, branching, conditional release, etc.) to address learner needs. The learning strategies can improve and personalize the learning of the student and can be adjusted as the course proceeds.

From the discussion in 9.2 the overall research question: “How prepared are higher education institutions for seamless learning?” is answered. What has become evident is that higher education institutions have different needs and situations, and the seamless learning experience design needs to be customized to fit into their context.

9.3 Results per Concept

This section aims at answering the sub- research questions of this study. They identify and address the specific needs to achieve a seamless learning environment in the higher education institutions respectively.

The sub-research questions are:

- What needs to change to improve the seamless learning approach at academic institutions?

- How can seamless learning be customized for a specific environment?

- How did seamless learning change from before to during COVID-19?

The questions are answered by a comparative analysis of the specific concepts in each country. The results of the “NO” answers in each graph indicate the gaps that are identified in each country and are the specific needs that need to be addressed for a customized seamless learning experience for each country. These findings answer the second sub-research question. The answers to sub-research question 3, are found in the comparison between the “YES” and “NO” answers as indicated in each country.

9.3.1 Comparative Analysis per Concept -Between Countries

For the comparative data analysis, the “YES” and “NO” answers from the questions based on the concepts, were counted and combined as a value. The total number of “YES’ and “NO” answers of each sub-concept are visually presented in the form of comparative graphs per sub-concept and are discussed in each chapter respectively. The total numbers are useful to indicate the existence or non-existence of concepts to establish whether or not a seamless learning experience could be followed for that specific course/class/program. The missing components (“NO” answers) can be considered as gaps to improve the future designs of the specific courses or as areas to conduct further investigation. The overall comparison per concept is portrayed in the following findings:

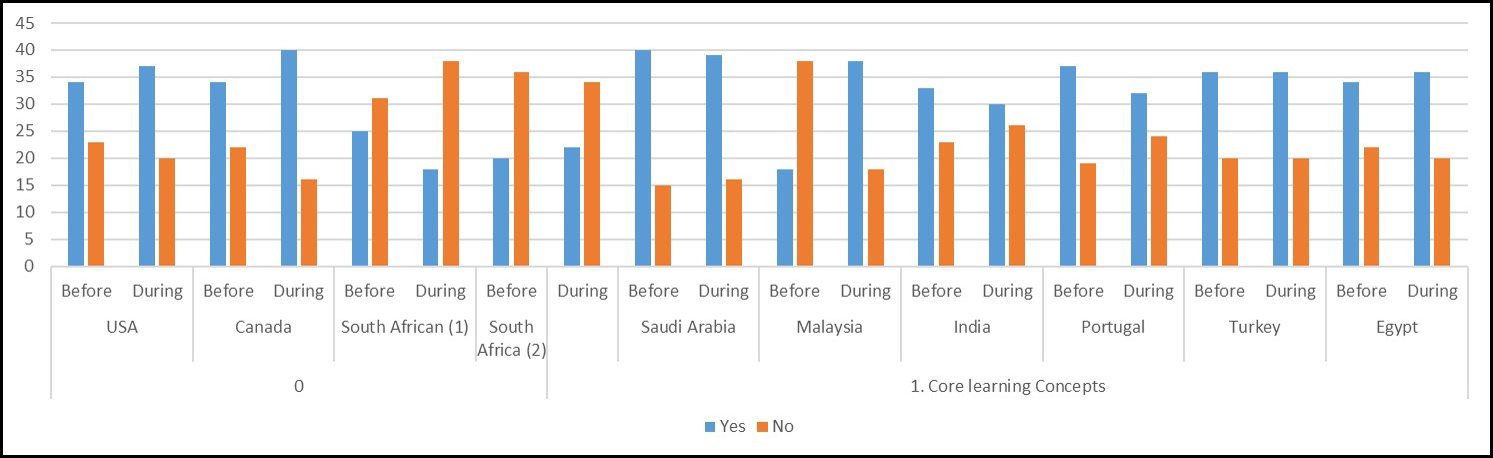

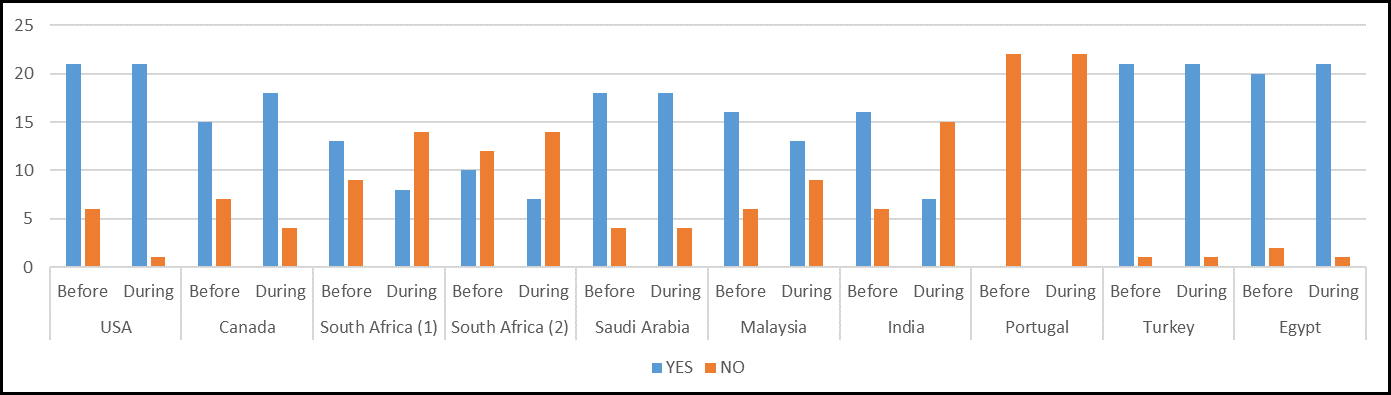

9.3.1.1 The Core Concepts of Seamless Learning Combined Results

As explained in 9.2.1 the core concepts of seamless learning focuses on pedagogical approaches and modalities for learning that were applied before and during COVID-19.

Figure 9.7

Core concepts of seamless learning – combined results

The combined comparison of the seamless learning concepts between the countries, indicates that the countries with most improvement during COVID-19 include the USA, Canada, South Africa 2, and Malaysia. The institutions where seamless learning decreased during COVID- 19 include those located in South Africa (institutions #1 and #2), Saudi Arabia, and Portugal. The institutions where no change was indicated are located in Turkey and Egypt.

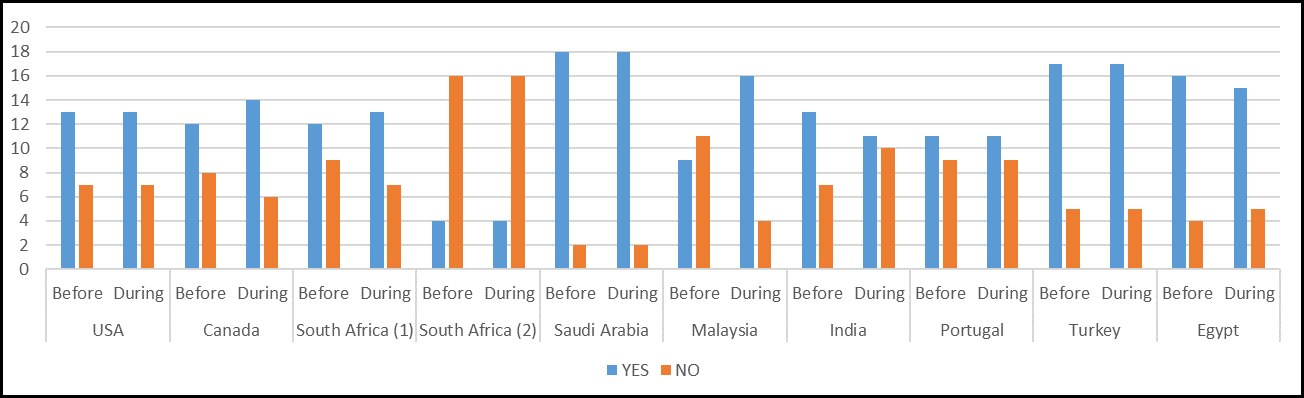

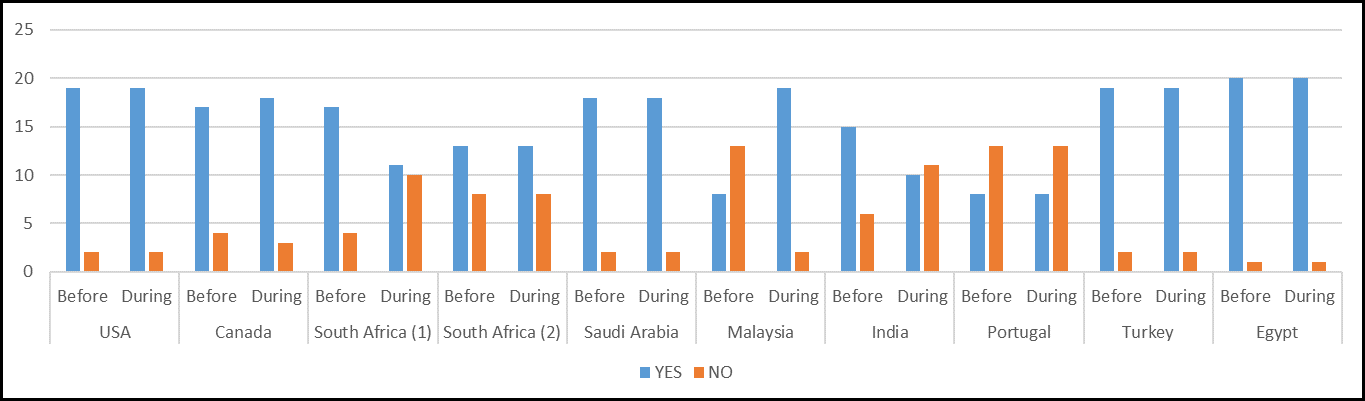

9.3.1.1 Positive Concept Combined Results

During the pandemic students showed that they had the capacity to become more reliant on their own ability and on technology than on the instructor’s instructions when their classes had to move from face to face to remote learning. This illustrates one of the positive concepts described in this study. More sub-concepts are presented in 9.2.2.

Figure 9.8

Positive concepts – combined results

The institutions that indicated improvement of positive concepts include those in Canada, South Africa, and Malaysia. The institutions that indicated no change are in the USA, Saudi Arabia, Portugal, Turkey, and South Africa (institution #2). The institutions where a decrease of positive concepts are indicated are located in India and Egypt.

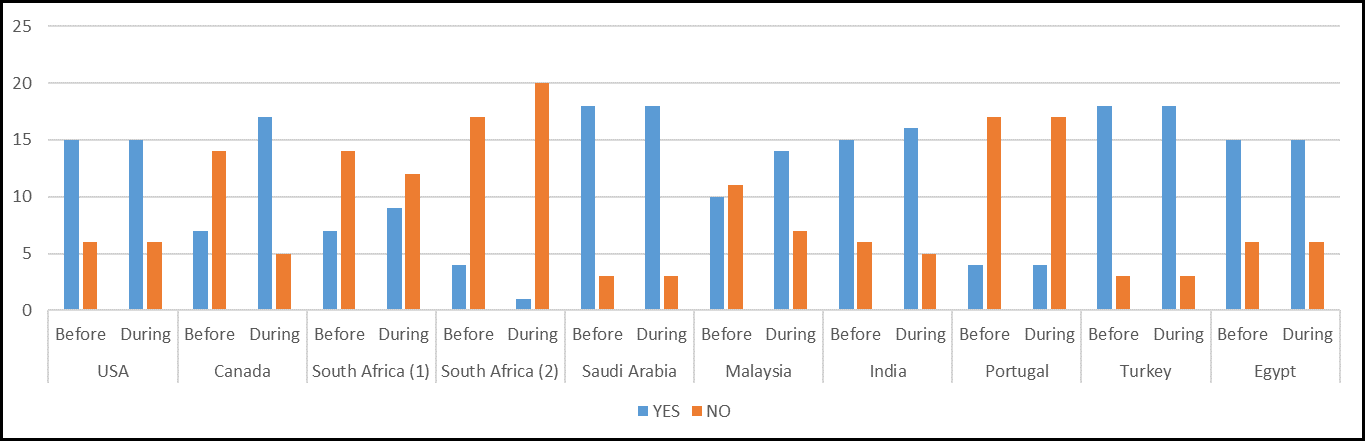

9.3.1.2 Practical Concepts Combined Results

Practical concepts as mentioned include access to hardware, software, support, and training. The specific sub-concepts are explained under 9.2.3. Without practical concepts, seamless learning would be impossible as they comprise the actual capacity, resources, and supports that facilitate the connections across physical, digital, social, formal educational, and workplace environments.

Figure 9.9

Practical concepts – combined results

Access to technology is a significant concern in terms of expanding the digital divide. The results in the graph indicate that practical concepts in institutions such as those in the USA, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey remained consistent and unchanged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas practical concepts were showed increase in the Canadian and Egyptian institutions but fell dramatically in South Africa (institutions #1 and #2), Malaysia and India. The institution located in Portugal indicated no positive concepts before or during COVID-19 is Portugal.

9.3.1.3 Human Concepts Combined Results

Detailed human sub-concepts are explained in section 9.2.4. Without understanding the needs of the students and how they learn, the other concepts are hollow. The success of the student is the center of this study, and the human concepts need to be included for seamless learning.

Figure 9.10

Human concepts – combined results

The increase of human concepts during the pandemic are found in the Canadian and Malaysian institutions, whilst they stayed the same in the institutions located in the USA, South Africa (institution #2), Saudi Arabia, Portugal, Turkey, and Egypt and decreased in South Africa (institution #1) and India.

9.3.1.4 Design Concepts Combined Results

The necessary sub-concepts for design are available in the 8.2.5 section where they are described in more detail. If a course is designed well and many of the aspects mentioned in the SLED model are added, a successful outcome and experience for the student is more likely. If the design is ill-conceived, the learning experience will likely be less favorable.

Figure 9.11

Design concepts – combined results

According to the combined data, the course design considered by the participants from institutions in the following countries remained consistent during COVID-19. These institutions are those in the USA, Saudi Arabia, Portugal, Turkey, and Egypt. Institutions that indicated changed or improved design include the Canadian, South African (institution #1), Malaysian, and Indian institutions. The design criteria decreased (more “No” answers) in South Africa, institution #2.

Even if only a small number of the seamless learning concepts were incorporated into teaching and learning practices during the pandemic, the institutions appear to have already incorporated some seamless learning practices of some sort. Innovative approaches were certainly implemented—including interactions through virtual classes and WhatsApp (2022), and messenger. The students appear to have become much more self-reliant—whether voluntarily or compelled by the crisis situation. The results of this study are further discussed per country in the next section (9.4).

9.4 Results per Country

For the comparisons of the concepts per country, the total numbers are calculated as a percentage. The percentage is calculated from the number of responses in relation to the total number of criteria. Since not all concepts have the same total number of criteria, converting the numbers to a percentage of the total offers a consistent guideline for the specific concepts.

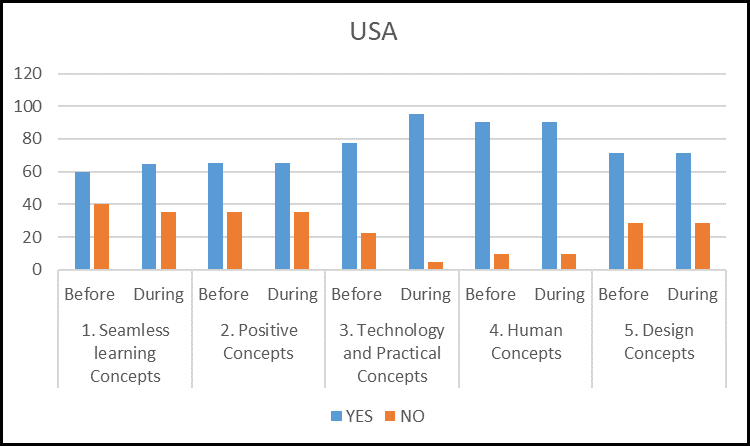

Figure 9.12

USA overall results

9.4.1 USA Overall Results

In the American institution, most of the seamless learning concepts were included in the identified course before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (from 60% to 90%). An area where seamless learning practices can be improved is in terms of the seamless learning/pedagogical concepts and the positive concepts. The design concepts remained constant at that time as most of the necessary components were already in place; therefore, it would be interesting to examine the course designs more closely. The technology and practical concepts changed the most during COVID-19 as the students either had to work from home or could attend classes. This American institution offered a hyflex mode in which students could choose to stay home or attend classes face to face as both modes were offered.

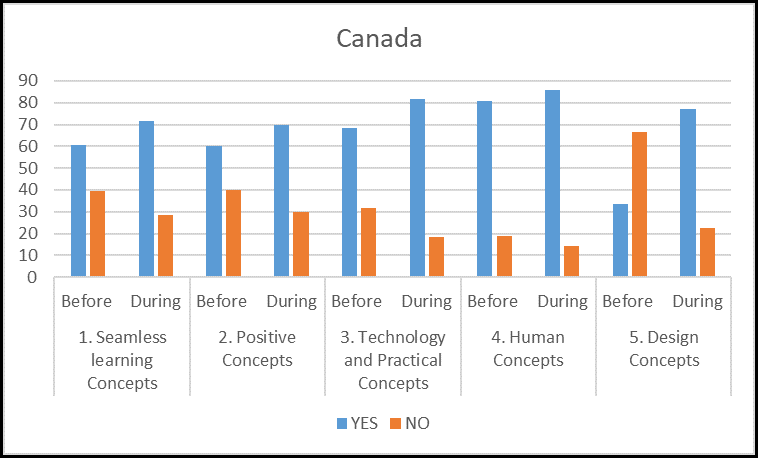

Figure 9.13

Canada overall results

9.4.2 Canada Overall Results

In the Canadian institutions, all seamless learning concepts increased (more “Yes” responses) during COVID (from 60 -86%). The design concept shifted dramatically to in an effort to adapt to the new situation in which learning had to take place remotely. As with the institution from the USA, more work can be done to integrate all concepts to achieve a more seamless approach to learning in the future. Greater attention can be added to their positive concepts.

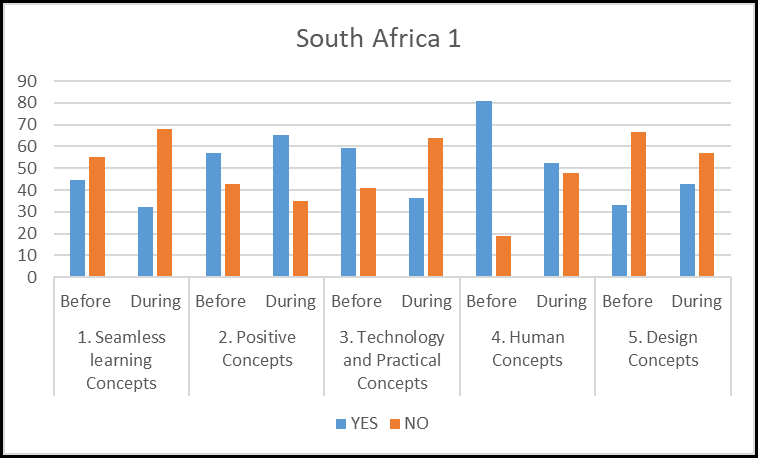

Figure 9.14

South Africa (1) overall results

9.4.3 South Africa (1) Overall Results

The recognition of the SLED concepts in institution #1 in South Africa clearly varied but can be explained. Whilst the positive and the design concepts improved from before the pandemic to during the pandemic, the seamless learning concepts appeared more difficult to implement during COVID-19 most likely due to lack of accessible technology and the lack of practical concepts in place. Furthermore, human concepts where training and skills were needed for adaptation, were less developed (i.e., skill sets, training, time for training, and mindset). Nevertheless, faculty, staff, and students adjusted as they were able and some aspects of seamless learning were evident even if not all concepts were optimally included.

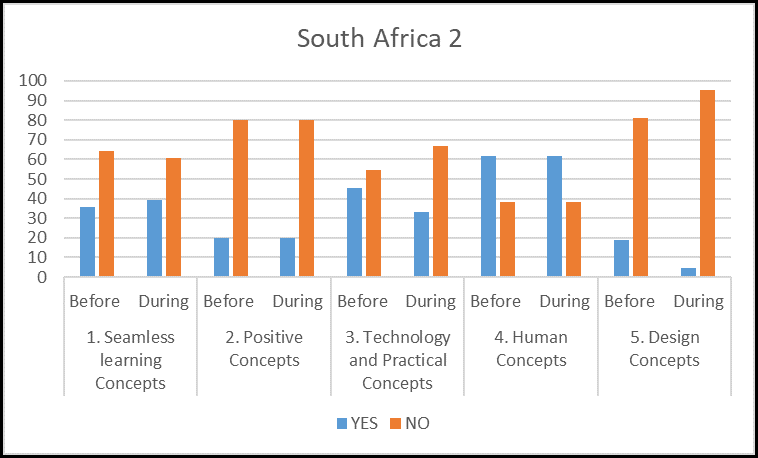

Figure 9.15

South Africa (2) overall results

9.4.4 South Africa (2) Overall Results

The Figure 9.15 of South Africa institution #2 indicates that all concepts had more “NO” than “YES” answers except for the human concepts. There was a slight increase in terms of the seamless learning pedagogical practices as instructors adjusted their teaching approach since students had to engage online. No change in terms of positive and human concepts are indicated before and during the COVID-19 lockdowns. The technology and design concepts were less evident during COVID-19. Overall, the institutional environment has much room for integration of seamless learning at most levels; nevertheless, there was some evidence of seamless learning practices even during COVID-19.

Findings Regarding South Africa (1) and South Africa (2) Analysis

The inclusion of two distinct institutions from one country provided an interesting window of observation. Compared to the South Africa institution #1 analysis, the South Africa institution #2 environment will need to make more adjustments to support and optimize the seamless learning approach. Reasons for greater challenges in the South Africa institution #2 environment include the remote situation of the campus that lies in the Drakensberg mountains on the border between South Africa and Lesotho. Furthermore, access to internet and technology at South Africa institution #2 has received less attention than necessary to ensure sufficient access to online learning. In order to achieve better results the design concepts will need further consideration so that the other concepts can develop and mature.

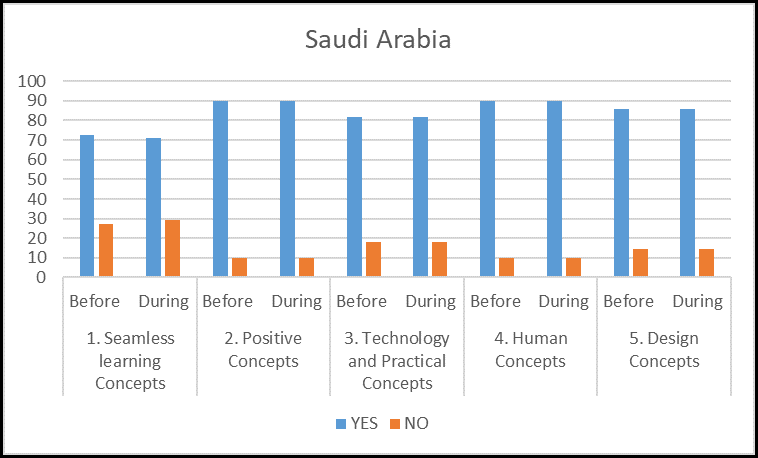

Figure 9.16

Saudi Arabia overall results

9.4.5 Saudi Arabia Overall Results

The graph depicting the responses from the participant from the Saudi Arabian institution indicates that all concepts are well established and continued to be well represented during the COVID-19 pandemic. The highest-ranking concepts (i.e., most “Yes” responses) include positive and human concepts, and the design concepts with technology concepts not far behind. Even though the Saudi institution has included between 70- to 90% of the criteria for an optimal seamless learning experience, some aspects need to be included to optimize the seamless learning experience of the students in the future. The two concepts that could be better developed are the design concept and seamless pedagogical concepts.

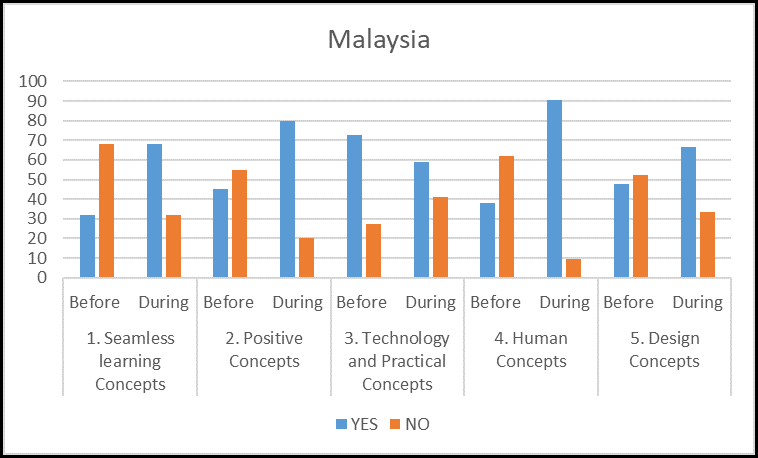

Figure 9.17

Malaysia overall results

9.4.6 Malaysia Overall Results

Whilst most of the seamless learning concepts improved during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Malaysian institution, the technology and practical concept decreased (i.e., fewer “Yes” responses). The main reason for the decrease can be explained by the geographic location of the students. Most of the students attending this institution lived far away from the campus and lacked consistent connectivity and sufficient bandwidth. Therefore, the students had limited access to the learning material. The positive, human, design, and seamless learning concepts reflected these challenges. Despite such challenges was difficult, the Malaysian instructors and students were still able to achieve a relatively high level of seamless learning (between 60 and 90%).

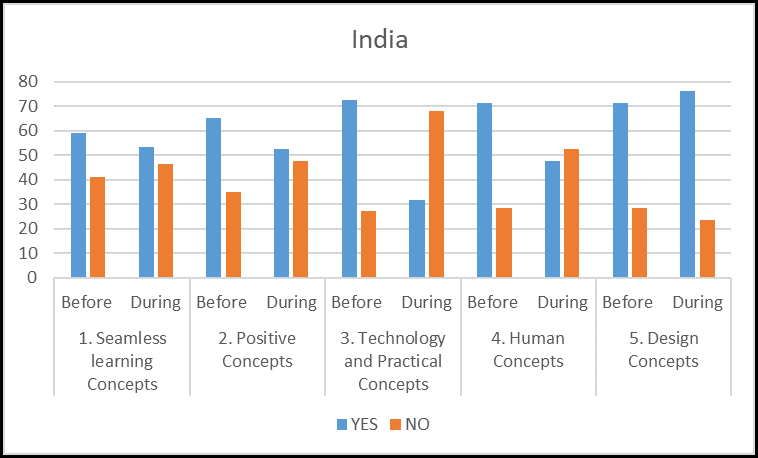

Figure 9.18

India overall results

9.4.7 India Overall Results

Even though most concepts decreased (i.e., fewer “Yes” responses) during the COVID-19 pandemic, the design concepts increased. The challenges of instructing students who were no longer on campus are clearly visible in the Indian institution, but in keeping with the other countries in this study, the responses suggest a relatively high seamless learning experience for the students (between 50 and 75%). The greatest challenges appear to be the technical and practical concepts both before and during COVID-19.

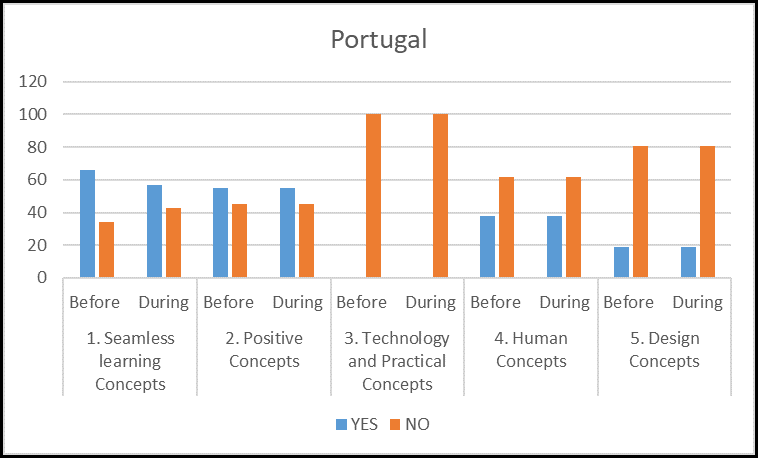

Figure 9.19

Portugal overall results

9.4.8 Portugal Overall Results

The results from the institution in Portugal indicate that hardly any changes took place between the time before and during COVID-19 for most of the concepts including the positive concepts, human concepts, and design concepts. The seamless learning core concepts (i.e. pedagogical concepts) decreased, and the technology and practical concepts appeared rather challenging. These results indicate that the Portuguese institution has much room to expand its implementation of teaching and learning practices and infrastructure across all the SLED concepts to achieve a more effective seamless learning experience for the students.

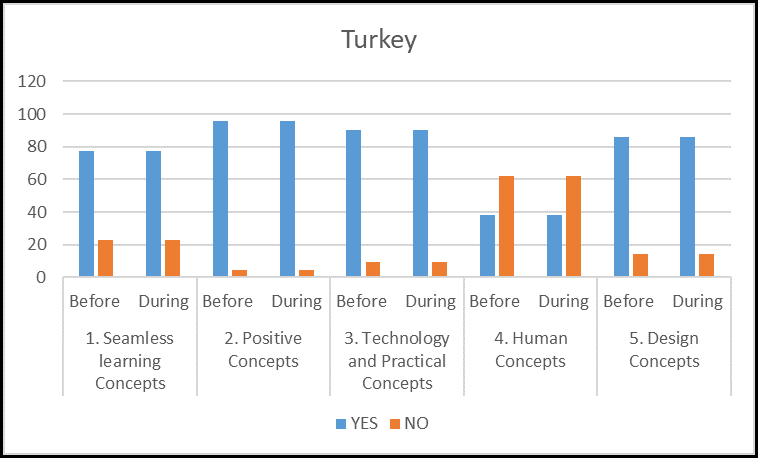

Figure 9.20

Turkey overall results

9.4.9 Turkey Overall Results

According to the responses from the participant from the Turkish institution, all concepts stayed the same before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The positive concepts are the highest (83%), and the human concepts the lowest (38%). The human concepts result suggests that specific attention must be paid because the “NO” answers are much higher than the “YES” answers. Despite these challenges, a seamless learning experience for the students appears relatively well maintained before and during COVID-19, with high percentages between 77 and 95%.

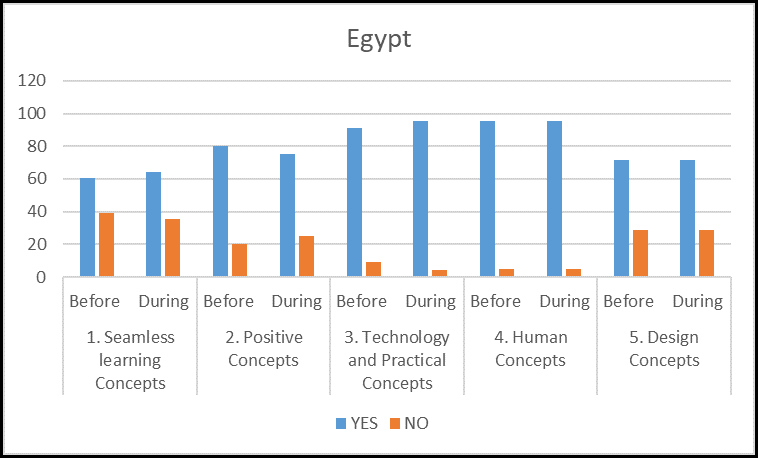

Figure 9.21

Egypt overall results

9.4.10 Egypt Overall Results

According to the findings for the institution in Egypt, the graph indicates that most of the concepts of seamless learning either remained the same or increased (i.e., more “Yes” responses) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The greatest improvements were identified in the seamless learning pedagogical approach and the technology and practical approach, whilst the human concepts and design concepts stayed the same and the positive concepts decreased. The differences between the concepts both before and during COVID-19 are relatively low. These findings indicate that the seamless learning experience could continue at a higher intensity during COVID-19 (between 60%-90%). However, most of the concepts could still be implemented at a greater rate in the future.

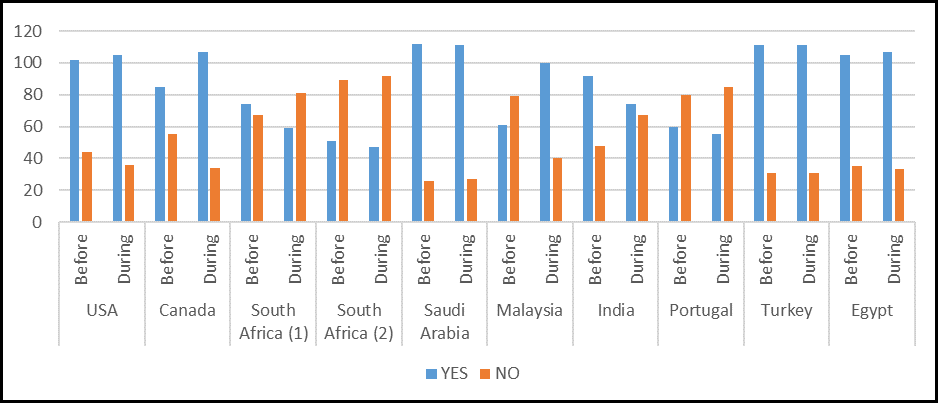

Figure 9.22

Combined overall results per country

9.5 Combined Overall Total Results per Concepts per Country

The combined data from all the criteria of the nine countries (including South Africa institution #1 and South Africa institution #2) are represented in Figure 9.22. The overall picture is quite astonishing. Most of the participating countries either continued with the approaches they had applied before the COVID-19 pandemic or showed a slight increase in the “YES” and a slight decrease in the “NO” answers. These observations are made in particular in the institutions such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey where most of the “YES” and “NO” answers stayed the same before and during the pandemic. In the institutions in USA and Egypt, a slight increase in the “YES” and a slight decrease in the “NO” answers is observable. This may be an indication that these countries already included many of the aspects that would support a seamless learning approach and were able to continue working with minimal adjustments during the COVID-19 pandemic, when on-campus classes moved to remote teaching. The institutions with an increase of “YES” answers during COVID-19 include those located in Canada and Malaysia. The institutions that indicate a decrease of “YES” answers include those in South Africa institution #1, India, and Portugal. Interestingly, South Africa institution #1 (urban campus) and South Africa institution #2 (rural campus) do not indicate the same number of “YES” and “NO” answers. It is thus assumed that the South Africa institution #1 campus was better prepared (perhaps better funded) for seamless learning before COVID-19 than the South Africa institution #2 campus. Although the majority of answers, lie in the “YES” area, the many “NO” answers indicate that there are still avenues for increasing seamless learning practices and infrastructure in all mentioned countries.

9.6 Conclusion

The main research question of this study is “How prepared are higher education institutions for seamless learning?”. The findings indicate challenges and successes that are not identical from one institution to another. Even though the criteria used for the survey to establish an answer (or several answers) to the research question are the same for all courses and institutions, they offer the opportunity for thoroughly examining specific institutional contexts and determining specific needs. The findings also indicate that “being prepared” for a seamless learning environment is possible on several levels. For example, a university may fulfill all criteria in terms of technology and access but may lack a seamless learning pedagogical strategy. Or an environment may have very little access to technology but uses its human concepts optimally.

This finding also answers the sub-questions.

1.1 What needs to change to improve the seamless learning approach at academic institutions?

The criteria under each concept and sub-concepts are clear indicators to identify the areas that need improvement. For example, the “No” answers indicate the gaps that may need to be considered. With this information a useful analysis can be made, and a specific strategy can be planned and implemented.

1.2 How can a seamless learning be customized for a specific environment?

Since the specified seamless learning criteria can be utilized to analyze a specific course in a specific environment, a very specific solution can be designed to address the specific needs of that course. These answers also highlight the usefulness of the survey/checklist to establish whether a course or university is “seamless learning ready”. The detailed questions may take time to answer but are extremely helpful to identify the strengths and weaknesses in a course. For this study the additional value lies in the descriptions—across the same criteria—of countries and environments of the various international universities included in this study.

The most important finding of the combined analysis is that all countries persevered, adapted, and succeeded in teaching during COVID-19. Even through the varied challenges, they could all apply some levels of seamless learning. Sustaining the core work and responsibilities of their institutions through the pandemic suggests that seamless learning is possible even though a course does not fulfill all criteria. Yet, the seamless learning criteria provides an excellent guide to establish where the approach can be improved to achieve an even better seamless learning experience. For example, in environments where there is less access to technology and networks, the pedagogical approach could be changed to accommodate and foster enrich the learning experience.

Developing countries and less privileged areas around the world may be under the impression that seamless learning cannot be effective in their environment when their institutions lack state of the art technology. This study has shown that success is less dependent upon state-of-the-art technology to achieve a seamless learning experience for the students; rather, that simpler technology can be used along with, for example, pedagogical, positive, practical, human and design concepts. It is also important to remember that all the concepts in the SLED model contribute to and co-create a better and richer seamless learning experience. Even if cellphone signal is only available by standing in the middle of a road or climbing a tree, which can be the case in areas of low internet coverage such as many rural areas, learning does not have to stop there.

Besides analyzing a course by using the proposed checklist, the instructional designer needs to work hand in hand with the content experts, keeping the access level, the background, and the environment of the student in mind to achieve an ultimate customized seamless learning experience for the students. By following these guidelines, the learning experience will prepare the student for a rich intellectual world as well as the world of work regardless of pandemics or other challenges.

9.7 Recommendations

In conclusion the following recommendations are proposed from this study.

- To use this study as a reference book for better understanding of the SLED terminology and concepts as discussed per chapter.

- To re-think curricula and assessments when applying the SLED approach.

- To use the specific criteria under each concept as a rubric and/or guideline for institutions around the world to improve and adjust their current practices.

- To apply lessons learned from this study in follow-up research studies.

- To add the SLED concepts to courses, curricula, strategies and policies.

- To improve quality and relevance by continuous updates based on the SLED concepts

- To incorporate learnings from dealing with technology infrastructures and support geared to a pre-pandemic era into an organizational framework.

- To identify employees (both faculty and staff) who can contribute to strengthening the organizational framework supporting teaching and learning in a setting of formalized and focused effort i.e. design a strategy and implement it with sufficient resources.

- To bridge the gap between the organizational knowledge of the users’ needs and the users’ knowledge of available technology, facilities, or support – for instance through mapping and analyzing the available technology and facilities, user learning patterns (Learning Analytics) and learning spaces in the individual HEI by using BI-reports that can work as a dialogue tool to find these gaps.

- To find sustainable business funding models for HE – engaging in UNs 4th goal: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”.

- To optimize current available technology at respective HEI for optimal results. Example using WhatsApp for lectures.

- To connect the learning process to real world needs, market knowledge, business practices and models, problem-solving and analytical skills are required.

Seamless learning has evolved over the years from inside and outside classroom experiences as suggested by Seymour Papert (1993) to the opportunity of including mobile technology as part of a continuous and ubiquitous learning. Greater mobilities have given students opportunities to pursue their interests further and has expanded seamless learning experience opportunities for all. This approach can become not only a part of the classroom but a part of life more generally.

How to apply the seamless learning approach for pedagogical environments can seem rather daunting as complexity and contextual change necessitates careful consideration for appropriate strategies, resources, and policies, and supports for each specific learning environment. This study demonstrates the application of how the SLED model can be implemented by firstly understanding what is already in place by using the SLED criteria as a matrix and by analyzing the data and envisioning what can be modified and improved upon. The next step of this longitudinal study is the inclusion of more countries to participate in this study to establish a better baseline and the application of the findings in specific courses to better understand each criterion within specific course contexts. In addition, subsequent studies will seek feedback from students and their perceptions and experiences.

The goal of implementing the SLED model is to improve the level and quality of learning and to offer an experiential and relevant education to students in higher education around the world with specific focus. As mentioned, the success of a seamless learning experience lies in the design, which is the responsibility of a team that works with the instructional designer but also in the implementation, which lies with management of higher education institutions and finally in the including the concept into the policies of the respective institutions and also in the education ministries.

Seamless learning is thus opening the opportunities for personal and individualized learning where each student is responsible for his own progress and where he or she can take their learning beyond traditional expectations. Thereby achieving a learning experience that will equip the student to achieve the highest level of learning as supported by the Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom’s et al.; 2000) and to be prepared for a world that expects more from graduates than theoretical knowledge.

References

Alessi, M. S., & Trollip S. T. (2001). Multimedia for learning: Methods and development. Allyn & Bacon.

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. David McKay Company

De Villiers, F & Hambrock, H. (2022) Designing a seamless learning experience design (SLED) framework in higher education based on global perspectives. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning (EJEL). (in press).

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Association Press.

Markowitz. T. (2020, July 9). The power of peers in higher education. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/troymarkowitz/2020/07/09/the-power-of-peers-in-higher-education/?sh=596282dd313c

Mateev, A. & Milter, R. (2010). An implementation of active learning: Assessing the effectiveness of the team. Infomercial assignment. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 47(2), pp. 201–213.

Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. Basic Books.

Pombo, L., Loureiro, M. & Moreira, A. (2010). Assessing collaborative work in a higher education blended learning context: Strategies and students’ perceptions. Educational Media International, 47(3), pp. 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2010.518814

United Nations (2022a). Global citizenship education. https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/page/global-citizenship-education

United Nations (2022b). Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

WhatsApp LLC (2022). WhatsApp: Simple. Secure. Reliable messaging. https://www.whatsapp.com/