Chapter 5: Human Concepts

Ramesh Sharma and Mohamed A. Ahmed

Background and Introduction

Human concepts constitute a significant part of human cognition and learning. Mareschal et al. (2010) in their book, The Making of Human Concepts, pondered over the uniqueness of human concepts in the background of evolutionary history and how the convergence of personal and social traits by mixing with biological abilities played its role in the emergence of human concepts. This chapter deals with different facets like skills, training, norms and convictions, equality, inclusivity, mindset, and outlook (positive or negative) of teachers and students before and during COVID-19. Teachers’ and students’ cognitive concepts have a significant impact on their abilities in dealing with world issues. Postmodernism in conjunction with the power of the Internet has contributed to the scale, speed, and skills of seamless education. The dynamics of the current global and interconnected society are posing new opportunities and challenges to the teaching and learning ecosystem. For effective engagement in educational transactions, three kinds of interactions are prominent: teacher-learner interaction, learner-learner interaction, and learner-content interaction (Moore, 1989). In terms of technology deployment and integration to teaching, learning, and assessment, we find that the interaction between humans and computers (i.e., hardware, software, and infrastructure) has penetrated nearly all aspects of teaching and learning. In addition to the technology aspect, human computer interaction has a human side as well. It has an impact upon social relationships, organizational development and individual human performance and intelligence (Sarmento, 2004).

Seamless education calls for application of digital tools for enhancement of human performance in a diverse range of educational contexts. There are significant implications of seamless learning for instructional technology, curricula, and other support systems. Over the past century, we have witnessed the adoption of radio, television, computers, satellites, and mobile technology in education. Modern digital technologies have made it simple and impactful to use digital text, audio, video, animations, graphics, and simulations on the desktop machines and over the Internet. Such human-computer interaction facilitates various forms of communication (verbal and non-verbal), human perception (visual, tactile, and/or auditory) and to the modern web 3.0 technologies that include immersive learning experiences. Human and technology integration has become quite pervasive and thus behooves educators to pay greater attention to not only to user interface design, but also to user experience and other dimensions of human psychology, behaviour, and information systems development. In terms of human concepts and technology, a variety of issues emerge such as learner characteristics and needs, computing environment design, and the kinds of tasks to be performed. A challenge here to examine and reduce the gap between organizational needs and support for teachers and learners (Zhang et al., 2005). Human concepts in seamless education is an emerging area of interest which aims at understanding, designing, and implementing different interfaces between humans and computers so that the educational systems become not only useful but also usable, engaging, and accessible (Zhao et al., 2016). The complexity or simplicity of a system depends upon three basic variables: time, accuracy, and volume of information (Sosnin, 2018). One of the approaches to reduce complexity is to coordinate effective, ubiquitous technology integration across human activities and focus on experiential learning. This chapter presents the findings on such human concepts and acquisition of skills and abilities.

5.1 Skills Set

The quality of a learning intervention relies on the knowledge and skills of the stakeholders. Some of the most important skills that are needed in this context are discussed below.

5.1.1 Computer Literacy of Students and Instructors is Problematic

In the context of seamless learning, the application of knowledge and computer literacy of instructors and learners represent a significant underpinning. Literacy skills can be classified into various groups such as academic literacy, numeric literacy, or digital literacy. Academic literacy pertains to performance in school-based activities and the achievement of a learner in a subject area. Computer or digital literacy refers to the skills of a person in their ability to use digital devices and internet-based services. Digital literacy is a “set of skills required by 21st Century individuals to use digital tools to support the achievement of goals in their life situations” (Fu, 2013 as cited in Reddy et al., 2020, p. 66).

Different agencies like OECD, Partnership for 21st (P21) Century Skills, the World Economic Forum and others have identified various skills (Schleicher, n.d.). Some of them pertain to new technologies and how such technologies can be used effectively. The P21’s Framework for 21st Century Learning (2019) identified three skills: Life and Career Skills, Learning and Innovation Skills (including critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity), and Information, media, and technology skills. In the context of seamless education, the learners and teachers are expected to exemplify literacy, life skills, and learning skills. Diversity plays a great role here on how learning ecosystems integrate seamless technology for building content knowledge, communication, and problem solving (Lawrence et al., 2021). Globally, attaining digital literacy is a serious concern (Biezā, 2020) although the access to Internet has gradually increased, more than half of the world population is connected to the Internet (International Telecommunication Union, 2021). The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) also reported that stronger ICT skills are required for connecting people (International Telecommunication Union, 2018). One of the reasons for not taking good advantage of access to the Internet is the lack of or inadequate ICT Skills (International Telecommunication Union, 2018). Digital literacy involves more than simply using a computing device or making online searches (Buckingham, 2015); learners should also be competent to evaluate and make critical use of information.

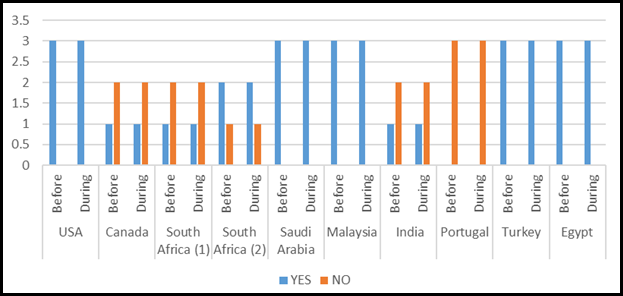

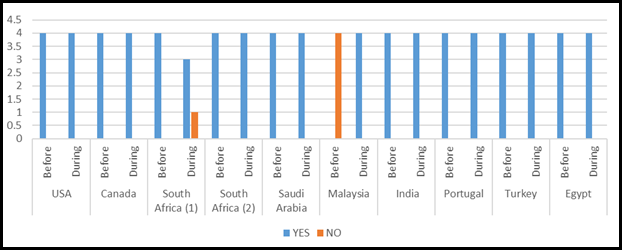

Figure 5.1

Skills Set

5.1.2 Application of Knowledge

Computer literacy skills of students and instructors are crucial for seamless learning. How the students and instructors use technology and to what learners employ critical thinking skills forms the basis of an effective skills set.

Figure 5.1 reveals interesting data in terms of computer literacy of students and instructors and their application of knowledge. Data from participating institutions in the USA, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Turkey, and Egypt (YES=3) indicate that seamless learning concepts were applied in teaching approaches both before and during COVID-19. The participant from the institution in Portugal was a unique case (NO=3) having indicated that it did not observe digital literacy skills before or during COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of the Canada and Indian participants (YES = 1, NO = 2), before COVID-19 the teachers and learners used these skills but diminished during pandemic (the negative response is higher). Portugal reportedly observed no usage of skills either before or during the COVID pandemic. In the case of South Africa, the situation was different for (institution #1) and (institution #2) campuses. While South Africa (#1) did not report usage of computer literacy skills before and during COVID, the rural campus for institution #2 indicated a YES for both periods.

5.2 Time Consuming

Activities to improve and change any educational approach requires focus and planning because such processes are both time consuming and are discussed in more detail below.

5.2.1 Creation of Digital Activities for Instructors

A teaching-learning process involves a triad of technology, pedagogy, and content. Creating digital content and activities is a serious, challenging, and time-consuming process. Teachers as a subject matter experts need to devote a lot of time. In light of the challenges created by time-consuming activities and copyright issues, use of open educational resources has gained momentum (Thakran & Sharma, 2016). Thorne and Reinhardt (2008) created a bridging-activities framework used to augment technology-mediated language learning. Adopting this framework, Yeh and Mitric (2020) examined the usage of social media (Instagram) on a pedagogically focused project. With the advancements in technology such as artificial intelligence, natural language processing, virtual reality, and other technologies, creation of digital activities by the teachers have impacted their time, resources, and performance (Bongarzoni, 2020). The digitalization of education puts new demands not only on the teachers, but also requires the leadership to adopt a digital mindset (Hensellek, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic phase, educational activities were carried out in a type of emergency remote teaching modality (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020). This situation required leanring designers and teachers to plan and devise teaching and learning activities for synchronous and asynchronous settings. Seamless learning activities call for various types of interactions, i.e., learner-learner, learner-teacher and learner-content (Hamutoglu, et al., 2022; Moore, 1989). The educational activities need proper planning in terms of quality, accessibility, alignment with curriculum, promoting authentic learning and being learner centric (Nuninger, 2019).

5.2.2 Extra Work for Students

The learner-centric pedagogical digital learning experiences and activities must be designed to drive the desired behavioural change in the learners. The underlying principle for reflective and reflexive activities should lead to new pedagogical culture and encourage learner autonomy when appropriate. Different institutions use different digital learning management systems (Al Amoush & Sandhu, 2020) and digital tools for streamlining teaching and learning tasks. Effective implementation of digital technologies involves a great deal of time investment on the part of teacher to work on creating course materials in the form of lectures, multimedia, and assessment activities.

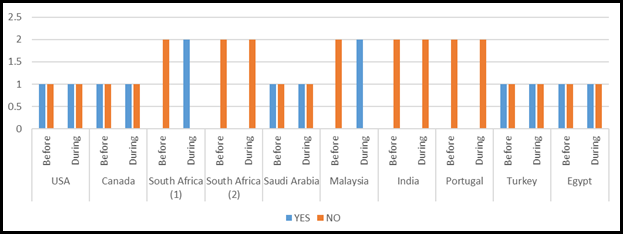

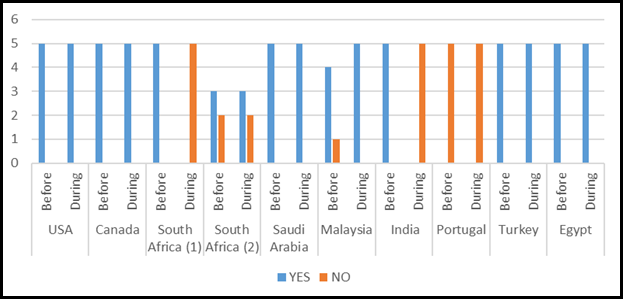

Figure 5.2

Time Consuming

Creation of digital activities and resources by the instructors, and also different approaches to evaluation of students’ assignments, are time consuming activities. Innovative assessment requires additional time dedication and management on the part of instructors—particularly when they lack prior experience. The institutions under study from the United States of America, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt indicated (Figure 5.2) that while it was a time-consuming process before COVID (YES=1 in each case), it was less so for them during the COVID-19. One of the reasons for this may be the closure of educational institutions and a complete shift to online methodologies rather than blended approaches. The participants from Indian, Portuguese, and South African (institution #2) reported (NO=2) no time consumptions for creation of digital activities for instructors. For students, they reported extra-work at both before and during COVID-19. For the institutions from Malaysia and South Africa (institution #1) is similar, both reported no time consuming before COVID-19, but during COVID, they reported additional time consumption for creating digital activities. These results suggest that some institutions may not have established seamless learning practices, and thus had not spent time on designing their courses differently.

5.3 Training

Adopting new and unfamiliar learning approaches requires good training for all stakeholders. In the context of higher education institutions, the training needs of both students and instructors are included and explained in more detail below.

5.3.1 Student and Instructor Training

The COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated the move of teaching from the traditional face-to-face mode to at least a blended mode of teaching—if not the adoption of an exclusive, full-blown online mode of teaching. A number of factors will influence approaches to the mode of teaching and learning in the post-COVID-19 era for institutions around the world. One determining factor will be, once the impact of this pandemic subsides, is the decision to go back to doing what was done in the past? Can HEIs ignore all the progress they made for online learning, or is online or blended learning is the way forward? It is likely that education will not be the same again post-COVID-19. In some cases, faculty and staff lacked the preparedness and training to embrace technology in their teaching practice, and this affected teaching adversely as many struggled with a ‘trial and error’ approach. The reality is that peoples’ approaches to life and social interaction before the COVID-19 outbreak have been altered and continue to be altered in response to COVID-19. Hence, instructional and learning designers were to continue thinking in terms of re-planning curriculum for blended modes of teaching since the era of exclusive face-to-face teaching remains in a fluid state. In fact, a new dispensation can be foreseen whereby, hypothetically, a course that has no online components would no longer be approved by accrediting bodies for tertiary institutions.

Another change caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was that online curriculum and teaching material had to be made available within developing countries. This is something that, prior to the pandemic, many developing countries had never considered necessary nor had the resources to dedicate to such practices. In tandem, serious thought must be given to training the faculty and students for seamless integration of technology in education so that they can create, use, distribute, and interact with online tools and materials. Indeed, “creating a digital teacher with the qualifications and technical skills has become necessary” (Fayda-Kinik, 2022, p.32).

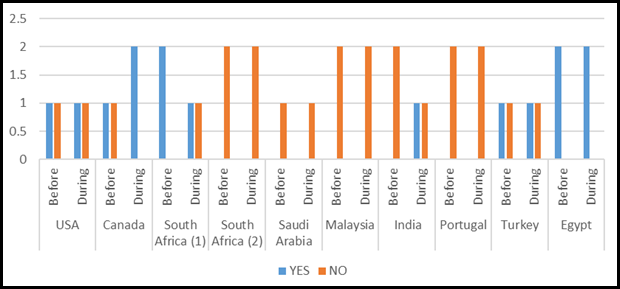

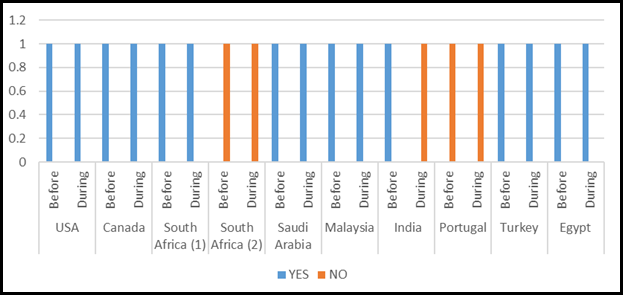

Figure 5.3

Training

Training is one of the most significant and crucial activities in any institution. Organizations provide training to their staff for upgrading the skills, increasing efficiency and productivity and to introduce the personnel to new work domains. It can be noted from Figure 5.3 that the institution participating in this study, particularly South Africa (institution #2), Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Portugal, reported no student training sessions and instructor training sessions either before or during COVID. In the Egyptian institution, there were training sessions to assist faculty and staff engage in seamless learning both before and during the COVID. In case of India, there were no student training sessions or instructors training sessions before COVID (perhaps because the teaching and learning methodologies were face-to-face primarily, although ICT tools were being used) nor during COVID, but the instructors could access training. It is possible that during the pandemic, the normal face-to-face teaching was suspended and, thus, all teachers had to shift to online. Many instructors in the Indian institution lacked trained in online teaching methodology. Increased training activities were noted for the Canadian institution during COVID and for South Africa (institution #1) before COVID phase. For the American and Turkish institutions, a similar situation can be noted where the training sessions were held before and during the pandemic.

5.4 Differences in Norms and Convictions, Cultures and Values

The technology applications have helped preserve, spread, and advance knowledge of teaching and learning and can help serve the differentiated learning needs of multicultural society (Sharma & Mishra, 2008). As technology integration into education opens new doors to global education, it brings to the fore the critical element of ethics, too. Trust and respect are the foundations of moral principles (Demiray & Sharma, 2009). The teacher takes on roles as a friend, a philosopher, and a guide to the learner, shaping their character to keep them on the right path. However, it is not only the learner, but the open-and-distance learning practitioners also face the ethical challenge of choosing appropriate pedagogy to serve broader social aims (Russell, 2009).

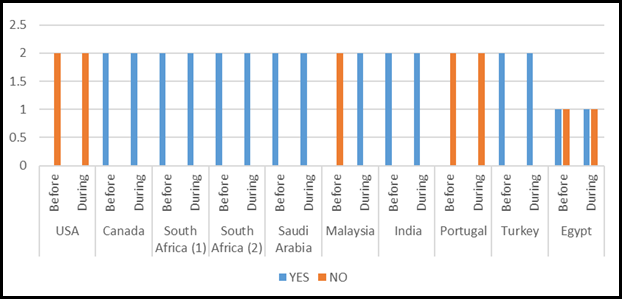

Figure 5.4

Differences in norms and convictions

Norms and convictions in any system are reflected in its organizational culture. This may include cultural differences among its personnel and the ethical norms and values the staff and organization adopt and exhibit. The institutions in Canada, South Africa (institution #1) and South Africa (institution #2), Saudi Arabia, India, and Turkey (Figure 5.4) reported a difference in norms and convictions both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The participant from India reported a high value placed upon inclusive learning in which students from different regions were encouraged to share their experiences and observation about their lives and worldviews. To this end, learning differences were acknowledged, and all policies and guidelines of the university and followed generally agreed upon ethical standards. For the Canadian institution, students in the Bachelor of Education Program generally come from a variety of cultural backgrounds and prepare to teach in cross-cultural environments. In the Canadian context, learners normally collaborate with peers from multiple cultural backgrounds and learn how to leverage technology to promote success in their own cross-cultural classrooms. For the Saudi Arabian institution, staff with different cultures are available and the institutions employ instructors from a variety of different cultures. Furthermore, the institutions must obtain ethical clearance directly from the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia has created a National Centre for e-Learning and Distance Learning, which determines all policy for technology in education. The participants from the USA and Portugal reported no difference in the norms and convictions either before or during the COVID phase. For the Malaysian institution, there was no difference in norms and convictions before COVID, but there were differences noted during COVID phase.

5.5 Equality and Inclusivity

Equality and inclusivity inside the educational system are very important because educational systems play an important role in the socialization and transfer of information to new generations. So many worldwide movements have worked ensuring access to quality learning, and from this, UNESCO’s (n.d.) education for all (EFA) framework outlines six goals:

- access to and improvement of early childhood care and education;

- access to and completion of free and compulsory primary education of good quality for all, especially girls, children in difficult circumstances and those belonging to ethnic minorities;

- appropriate and life-skills programmers for all young people and adults;

- improvements in levels of adult literacy;

- elimination of gender disparities and

- improving all aspects of the quality of education.

If we fail to achieve these goals inside our educational systems, education systems will fail our societies. Lynch, Baker, and Cantillon (2000) recommend that core social contexts are considered: inequality, economic relations, power relations, socio-cultural relations, and affective relations. In this chapter we focus on the following areas of equality as mentioned by instructors in the study by Hambrock et al. 2020. These include political equality, gender equality, racial equality, and disability accommodations.

5.5.1 Political Equality

It is important to consider the sociological characteristics of education because education plays an important role for anyone inside a community to learn and know his/her political rights and duties. This becomes evident where high voting activity of citizens correlates with a high level of education (Anduiza et al., 2019). Bobo and Licari (1989) are only two of many researchers who have explained the relationship of political equality and education, which improves group tolerance scales (Bobo & Licari, 1989).

5.5.2 Gender Equality

Gender equality is an important aim in education. Gender equality became more evident during the 70’s and became significant in educational policies in countries such as Finland, known for their extensive efforts and numbers of projects to achieve gender equality (Anduiza et al., 2019). Some studies indicate that gender inequalities declined in recent years in low-income countries especially with primary school qualifications while gender inequalities have not declined in higher education (Psaki et al., 2018). In Figure 5.5, the responses from participants in this study suggest improvements across all institutions in terms of gender equality.

5.5.3 Racial Equality

Racial equality is another important element inside our communities—especially to keep marginalized and racialized citizens safe and to provide access to education regardless of background. Policies affect such citizens’ development in every aspect of their lives. Jong (2013 writes of the struggle for racial equality in many countries such as the USA into the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the USA, the situation began to change because of the 1988 Education Reform Act on racial equality regarding opportunities in further education (Reeves, 1993); however, more work remains in the USA and other countries around the world. Figure 5.5 the participants from in South Africa and Malaysia indicate their perceptions that some inequalities linger.

5.5.4 Disability Equality

The number of students who joined the educational systems with already diagnosed disabilities is increasing because of of laws which legislate their inclusion in educational systems and support and normalize their integration into society. Many educational institutions around the world are, for example, required to provide facilities and make arrangements differently-abled students and accommodate their needs (Chan, 2016; Lindsay et al., 2018).

Figure 5.5

Equity and inclusivity

Equality and inclusivity of students and instructors are a fundamental value for seamless learning: ethically, education systems and curricula should promote equality and inclusivity. Figure 5.5 portrays the equality/ inclusivity of students and instructors and their application of knowledge before and during COVID-19. Data from the participants from the USA, Canada, South Africa (institution #2), Saudi Arabia, India, Portugal, Turkey, and Egypt (YES=4) indicate that seamless learning concepts were applied to achieve equality and inclusivity of students and instructors before and during COVID-19. Meanwhile while in the the South African (institution #1) situation shows that before the pandemic the equality and inclusivity was observed to be high (Yes= 4) but during the pandemic there was a change (YES=3, NO =1). It is possible that some students had continuing access to education during the COVID-19 pandemic while others did not. The situation for the Malaysian institution, on the other hand, offered a different profile than South Africa (#1); the data suggested limited or no equality and inclusivity before the pandemic (No=4), but improvements during the pandemic (YES=4). Thus, these research results show that equality and inclusivity were observed during the pandemic in most countries.

5.6 Mindset

Mindset has a significant impact on student and on instructor attitudes. Where the mindset is positive, mountains can move; where there is a negative mindset, very little progress is made and nothing happens. As part of mindset, the following aspects are included: intellectually stimulated students and staff, inspired students and staff, motivated students and staff, responsible students and staff, and good attitudes in class. Each of these aspects point to the intrinsic approach of the students and the instructors towards the learning experience. If any of these aspects are negative, a correspondingly negative situation can be expected. To improve the approaches and attitudes, regular communication between the stakeholders is recommended.

Rowntree (1987) in his classical work on assessment wrote, “Feedback is a lifeblood of learning” (p.24). Feedback is a crucial component in online courses which impacts engagement of the learners as well as the interaction between teachers and learners. For some participants, it can make the difference between finishing a course or dropping out. It is a motivating factor that many participants in a course may come to look forward to, seek affirmation, and gain a sense of social presence. Lack of meaningful feedback happens to be one of the biggest challenges that online learners face (Sharma, 2021). Teachers need to focus on how to create a conducive learning environment in online classrooms and prevent students from feeling isolated. Constructive feedback can encourage learners to reflect, handle criticism, learn more effectively, and stay motivated. However, providing feedback in an online course is not as straightforward. In fact, the lack of meaningful feedback happens to be one of the biggest challenges for online instructors and learners (Jones et al., 2022). It helps the learner to know whether they are within expected standards and criteria. Without feedback, learners may not know if they are reaching expected outcomes.

Part of the significance of feedback is to confirm if participants are on the right track or not. Without it, they can easily get discouraged and participation being affected negatively. The role of the facilitator is to provide direction and support to the participants helping them to progress from one level of learning to another. The critical aspect we should always consider in our online space is how to convey feedback to the students in timely and clear manners, so they recognize it, understand it, and act upon it appropriately. In the case of open and distance education learners, comments from the instructors on the assignments of students is crucial (Sharma & Rajesh, 2007). Properly structured, flexible, and repeated training for the teachers can play a great role in reducing or eliminating negative comments on course evaluations. In traditional, face-to-face teaching contexts, the facilitator’s gestures and other facial expressions could serve as feedback to learners. Such visual cues are, however, absent in online facilitation. As such, prompt and clearly articulated feedback is very important in online facilitation.

Figure 5.6

Mindset

A positive mindset in education plays an important role in improving the educational process by stimulating and inspiring students. The goal is to improve the educational environment by fostering and supporting motivated and responsible students. Figure 5.6 depicts the mindset ratings of the participants in this study. Data from institutions in the USA, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt (YES=5) indicate that the positive mindset aspects of seamless learning concepts were observed before and during COVID-19. While the responses from the participants from South Africa (institution #1) and India clearly show that before the pandemic, there was a positive mindset (YES=5); however, during the pandemic, there was a shift, and the positive mindset slipped (NO=5) during the COVID-19 pandemic in these countries. In contrast, South Africa’s (institution #2) situation shows that the mindset changed from (YES=3) before and to (NO=2) during the pandemic. Responses from the participant from Malaysia, suggest that the mindset improved from (Yes=4) and (No=1) before the pandemic to (Yes=5) during the pandemic. The participant from the Portuguese institution indicated no difference before and during the pandemic (No=5). These results may simply be a reflection of the diversity uniqueness of contexts and institutions.

5.7 Positive Outlook

The positive outlook criterion links the mindset of the students to that of the instructors. Challenges may change the positive outlook of a student such as feeling lost in an online course, which is very common. Some students may feel lost because they cannot find the instructions for the activity they are supposed to complete. They may not want to ask the lecturer or their peers. Students may not ask for assistance if the feel it might make them look incompetent or deficient. However, a situation such as this may be the result of poor course design in which the diverse experiences, needs, and characteristics of the learners was ill-considered? Another factor may be the diverse personality of students; for example, some may be submissive and some dominant. Learners’ personalities and proclivities becomes important in online discussion forums. How can shy or reluctant students participate? Instructor can address such issues by ensuring a comfortable and encouraging environment for everyone and by ensuring that everyone—not only the loudest—has a voice; ‘lurkers’ also add value to the learning environment. The instructor needs to notice the quiet participants and find strategies to gently encourage them to contribute. There should be rules and regulations (“netiquette”). Patience and open-minded approaches are crucial for the student.

Instructors should also facilitate and monitor class health. Respect, professionalism, and a positive attitude should be modelled for learners. (Adam et al., 2021). In addition, instructors need to carefully consider how to introduce learners to online so they can develop technological self-efficacy (Bai, 2022). Chen et al. (2021) in their study on psychological capital examined the effect of teaching beliefs on classroom management effectiveness. They reported that a positive and optimistic attitude of the teachers lead to significant improvements in learners’ abilities of word recognition, reading, and schoolwork (Kao & Chang, 2011a, 2011b). A positive mindset improves emotional well-being, results in better performance, and greater dedication to work commitments (Chen et al., 2014; Huang & Hwang, 2012; Jeng & Wu, 2012; Lee, 2009). Teachers with a positive attitude display altruistic behaviour (Huang & Hwang, 2012).

Figure 5.7

Positive Outlook

A positive outlook by the student and the teacher is a key to the success in learning. Figure 5.7 depicts the responses to the positive outlook question. Data from the institutions in the USA, Canada, South Africa (institution #1), Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Turkey, and Egypt indicate that seamless learning concepts were applied to achieve a positive outlook for students and instructors before and during COVID-19. The responses of the participant from India show that there was a positive outlook before the pandemic time, but that the attitude changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data from South Africa (institution #2) and Portugal indicate no difference in outlook before and during the pandemic. Institutions from most countries indicated improvements from before to during the pandemic while in other institutions experienced no improvements either before and during the pandemic are indicated. The reasons may be related to how the faculty/instructors and students reacted emotionally to the shift online during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Human concepts have a significant impact on the seamless learning. There are various dimensions of human concepts, including knowledge skills, digital literacy skills, creation of digital activities, training of teachers and students to use technology, and other pedagogical strategies. Other more important aspects such as equality, inclusivity, accessibility, ethics and norms, motivation, and a positive mindset are also important. To implement seamless education, new and innovative theoretical-practical knowledge is required. Teachers and administrators in these constantly changing times, need to adapt balance costs with quality. Human concepts encompass explicit and implicit factors for example communication, knowledge management, performance appraisal, and security of data. The energies and synergies of human capital need to be oriented towards bigger aims of education.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report (Whiting, 2020), 50 per cent of the labour force would need reskilling by 2025. This is happening in part due to an increase in technology adoption. The World Economic Forum notes that self-management skills such as resilience, stress tolerance, and active learning should be prominent. The findings of the study have shown that the institutions in the USA, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Turkey, and Egypt reported seamless learning concepts were applied in teaching approaches before and during COVID-19. The participant from Portugal did not observe human concepts before or during COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of the Canadian and Indian institutions, the teachers and learners used these skills before the pandemic, but the negative response was higher during the pandemic. While the participant from South Africa (institution #1) did not report usage of computer literacy skills either before or during COVID; on the other hand, the rural campus in South Africa (institution #2) indicated use of computer literacy skills. The creation of digital activities in the American, Canadian, Saudi Arabian, Turkish, and Egyptian institutions was reported to be a time-consuming process before COVID-19 but less so during the COVID. One of the reasons for this may be that they were already prepared for online teaching and learning before COVID-19.

The participants from India, Portugal, Malaysia, South Africa (institution #1) and South Africa (institution #2) reported little or no additional time consumption for the creation of digital activities for instructors; however, they noted extra-work for students both before and during COVID-19. Because of the haste in which universities had to transition, they may not have been able to spend time on designing online courses—let alone seamless learning experiences. No training was offered to students and teachers in the institutions from South Africa (#2), Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and Portugal either before or during COVID-19. In the case of Egypt, there were training sessions for methodologies for seamless learning at both before and during COVID-19. In the case of India, where there were no student training sessions or instructors training sessions before COVID-19, the instructors received training during the pandemic.

The computer literacy skills of the teachers and learners pose a challenge to meet the goals of seamless learning and, thus, there is an urgent need for more training programmes. Certain countries have implemented some measures in this direction; for example, in India the government launched a scheme called ‘Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya National Mission on Teachers and Teaching’ with the purpose of preparing faculty for academic leadership positions and for training them in using innovative pedagogy for effective learning outcomes with ICT as major focus area. Creating digital resources is a time-consuming activity. Yet, one of the major global achievements in this direction has been the promotion of open-educational resources (OER). The motto of OER is ‘there is no need to reinvent the wheel’ using the content which is already available under open license and studies have proved that they are equally effective as well as cost effective solutions.

The data regarding the Canadian, South African (#1 and #2), Saudi Arabian, Indian, and Turkish institutions had differences in norms and convictions both before and during the pandemic. The Indian participant reported inclusivity as essential for learning environments. For Canada, Students in Bachelor or Education program came from a variety of cultural backgrounds and were preparing to teach in cross-cultural environments. The Saudi Arabian institution had staff representing different cultures. Equality/inclusivity of students and instructors at the American, Canadian, South African (institution #2), Saudi Arabian, Indian, Portuguese, Turkish, and Egyptian institutions applied the seamless learning strategies for human concepts before and during COVID-19. Specifically, the USA, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt participants reported a positive mindset for seamless learning concepts before and during COVID-19.

These findings indicate that the implications of human concepts before and during the pandemic vary in impact and provide a significant rationale for planning and strategizing for seamless education in the higher education institutions. Additional research and encouragments for the governments and stakeholders to work more on these concepts would move seamless learning forward in all education levels.

References

Adam, M., Gameraddin, M., Alelyani, M., Zaman, G.S., Musa, A., Ahmad, I., Alshahrani M.Y., Alsultan, K., & Gareeballah, A. (2021). Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice concerning COVID-19 among undergraduate students of Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences at King Khalid University, Abha, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional surveyed study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 12, 789-797. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S314163

Al Amoush, A. B., & Sandhu, K. (2020). Digital transformation of learning management systems at universities: Case analysis for instructor perspective. In S. Johnson (Ed.), Examining social change and social responsibility in higher education (pp. 161-178). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-2177-9.ch012

Anduiza, E., Guinjoan, M., & Rico, G. (2019). Populism, participation, and political equality. European Political Science Review, 11(1), 109-124. http://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000243

Bai, X. (2022). Preservice teachers’ evolving view of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 17(04),212–224. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i04.25923

Biezā, K. E. (2020). Digital Literacy: Concept and definition. International Journal of Smart Education and Urban Society (IJSEUS), 11(2), 1-15. http://doi.org/10.4018/IJSEUS.2020040101

Bobo, L., & Licari, F. C. (1989). Education and political tolerance: Testing the effects of cognitive sophistication and target group affect. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(3), 285-308. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1086/269154

Bongarzoni, P. (2020). A new digital approach to strategic activities: Technologies and tools available with the consulting support. International Journal of Business Strategy and Automation (IJBSA), 1(2), 12-24. http://doi.org/10.4018/IJBSA.2020040102

Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to Corona Virus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3778083

Buckingham, D. (2015). Defining digital literacy – What do young people need to know about digital media? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10, 21-35, https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2015-Jubileumsnummer-03

Chen, P., Shen, M. & Hsu, Y. (2021). Psychological capital as a mediator: Effect of the teaching beliefs of classical reading program teachers on classroom management effectiveness, Journal of research in education sciences, 66(2), 207-239. https://doi.org/10.6209/JORIES.202106_66(2).0007

Chan, V. (2016). Special needs: Scholastic disability accommodations from K-12 and transitions to higher education. Current psychiatry reports, 18(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0645-2

Chen, P.-L., Hung, C.-H., & Yu, M.-N. (2014). Emotional well-being as a mediator between the relationship of psychological capital and depression in Taiwan college students. Journal of Educational Research and Development, 10(4), 23-45. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00332941221077026

Demiray, U., & Sharma, R. C. (2009). Ethical practices and implications in distance education: An introduction. In U. Demiray, & R. Sharma (Ed.), Ethical practices and implications in distance learning (pp. 1-9). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59904-867-3.ch001

Fayda-Kinik, F. S. (2022). The digital teacher: The TPACK framework for teacher training. In A. Afonso, L. Morgado, & L. Roque (Eds.), Impact of digital transformation in teacher training models (pp. 31-53). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9538-1.ch002

Hambrock, H., De Villiers, F., Rusman, E., MacCallum, K., & Arrifin, S. A. (2020). Seamless learning in higher education: Perspectives of international educators on its curriculum and implementation potential: Global Research Project 2020. International Association for Mobile Learning.

Hamutoglu, N. B., Özdamar, N., Gedik, N., & Kapkın, E. (2022). Designing and managing synchronous and asynchronous activities: The online training case for Faculty of Aeronautics and Astronautics staff. In G. Durak, & S. Çankaya (Eds.), Handbook of research on managing and designing online courses in synchronous and asynchronous environments (pp. 51-76). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8701-0.ch003

Hensellek, S. (2020). Digital leadership: A framework for successful leadership in the digital age. Journal of Media Management and Entrepreneurship (JMME), 2(1), 55-69. http://doi.org/10.4018/JMME.2020010104

Huang, L.-H., & Hwang, F.-M. (2012). The study on the relationships among psychological capital, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior. αβγ of the Journal for Quantitative Research, 4(1), 29-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14141

International Telecommunication Union (2018). Access to and use of ICTs keep growing but stronger ICT skills needed to connect people everywhere. [Press release]. https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/2018-PR41.aspx

International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2021). Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2021. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2021.pdf

Jeng, B.-J., & Wu, Y.-L. (2012). The psychology capital of special education teachers at the elementary school: The scale developing and relationship with job performance. Kaohsiung Normal University Journal: Education and Social Sciences, 33, 1-22.

Jong, G. d. (2013). The Scholarship, Education and Defense Fund for Racial Equality and the African American Organizing Tradition in the Era of Black Power. Journal of Contemporary History, 48(3), 597-616. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23488424

Jones, B.D., Fenerci-Soysal, H., & Wilkins, J.L.M. (2022). Measuring the motivational climate in an online course: A case study using an online survey tool to promote data-driven decisions, Project Leadership and Society, 3, 100046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100046.

Kao, W.-Q., & Chang, S.-L. (2011a). Analysis of submitted theses and dissertations from 1986-2010 that review the education of classics recitation in Taiwan and China (I). Legein Monthly, 437, 36-46.

Kao, W.-Q., & Chang, S.-L. (2011b). Analysis of submitted theses and dissertations from 1986-2010 that review the education of classics recitation in Taiwan and China (II). Legein Monthly, 438, 30-49.

Lawrence, S. A., Labissiere, T., & Stone, M. C. (2021). The 4Cs of academic language and literacy: Facilitating structured discussions in remote classrooms. In M. Niess, & H. Gillow-Wiles (Ed.), Handbook of research on transforming teachers’ online pedagogical reasoning for engaging K-12 students in virtual learning (pp. 297-316). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7222-1.ch015

Lee, H.-M. (2009). Preschool teachers’ psychological capital and its potential association between job performance. Journal of Child Care, 7, 1-23. http://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2017.050521

Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., & Carafa, G. (2018). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators of disability disclosure and accommodations for youth in post-secondary education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(5), 526-556. https://hdl.handle.net/1807/110497

Lynch, K. (2001). Equality in education. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 90(360), 395-411. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30095506

Lynch, K., Baker, J., & Cantillon, S. (2000). The relationship between poverty and inequality. [Draft paper]. https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/rest/bitstreams/4716/retrieve

Mareschal, D., Quinn, P.C., & Lea, S.E.G (2010). The making of human concepts, Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199549221.001.0001

Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

Nuninger, W. (2019). Common scenario for an efficient use of online learning: Some guidelines for pedagogical digital device development. In Pre-service and in-service teacher education: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (Management Association Eds.) (pp. 891-925). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7305-0.ch043

Partnership for 21st Century Skills [P21]. (2019). P21 framework definitions. http://www.battelleforkids.org/networks/p21.

Psaki, S. R., McCarthy, K. J., & Mensch, B. S. (2018). Measuring gender equality in education: Lessons from trends in 43 countries. Population and Development Review, 44(1), 117-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12121

Reeves, F. (1993). Effects of the 1988 Education Reform Act on racial equality of opportunity in further education colleges. British Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 259-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192930190304

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., & Chaudhary, K. (2020). Digital literacy: A review of literature. International Journal of Technoethics (IJT), 11(2), 65-94. http://doi.org/10.4018/IJT.20200701.oa1

Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing students: How shall we know them? (2nd edition), London: Kogan Page.

Russell, G. (2009). Ethical concerns with open and distance learning. In U. Demiray, & R. Sharma (Eds.), Ethical practices and implications in distance learning (pp. 64-78). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59904-867-3.ch006

Sarmento, A. (Ed.). (2004). Issues of human computer interaction. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-191-9

Schleicher, A. (n.d.). The case for 21st-century learning. OECD: Better Policies for Better Lives. Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/general/thecasefor21st-centurylearning.htm

Sharma, R. C. (2021). Opportunities and challenges of connections, trust, diversity, and conflict for motivation, volition, and engagement in online learning. In H. Ucar, & A. Kumtepe (Eds.), Motivation, volition, and engagement in online distance learning (pp. 49-67). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7681-6.ch002

Sharma, R. C., & Mishra, S. (2008). Technology and culture: Indian experiences. In T. Kidd, & I. Chen (Ed.), Social information technology: Connecting society and cultural issues (pp. 181-189). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59904-774-4.ch013

Sharma, R. C., & Rajesh, M. K. (2007). Tutor-marked assignments: Evaluation of monitoring in India. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 5(3), 10 – 27. http://asianjde.org/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/103

Siewert, C. (2001). Plato’s division of reason and appetite. History of Philosophy Quarterly, 18(4), 329–352. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27744897

Sosnin. P. (2018). “Introduction.” in Experience-Based Human-Computer Interactions: Emerging Research and Opportunities, IGI Global, pp.1-8. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2987-3.ch001

Thakran, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2016). Meeting the challenges of higher education in India through Open Educational Resources: Policies, practices, and implications. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24, 37. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.1816

Thorne, S., & Reinhardt, J. (2008). ‘Bridging activities,’ new media literacies and advanced foreign language proficiency. CALICO Journal, 25(3), 558–572. http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/11592

UNESCO (Bureau international d’éducation). (n.d.). Education for all. http://dmz-ibe2-vm.unesco.org/es/node/9704

Whiting, K. (2020, October 21). These are the top 10 job skills of tomorrow – and how long it takes to learn them. [Web log post]. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/top-10-work-skills-of-tomorrow-how-long-it-takes-to-learn-them/

Yeh, E., & Mitric, S. (2020). Bridging activities: Social media for connecting language learners’ in-school and out-of-school literacy practices. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT), 10(3), 48-66. http://doi.org/10.4018/IJCALLT.2020070104

Zhang, P., Carey, J., Te’eni, D., & Tremaine, M. (2005). Integrating human-computer interaction development into the systems development life cycle: A methodology. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 15(1), 29. http://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01529

Zhao, Y., Zhang, X., & Crabtree, J. (2016). Human-computer interaction and user experience in smart home research: A critical analysis. Issues in Information Systems, 17(3). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/HUMAN-COMPUTER-INTERACTION-AND-USER-EXPERIENCE-IN-%3A-Zhao-Zhang/575e6e71292e76f2bf06c4fd941b5fae5355cbbb#citing-papers