Chapter 3: Positive Concepts of Seamless Learning

Mohamed Osman El-Hussein and Helga Hambrock

Background and Introduction

The positive concepts of the study include the aspects that would have a positive effect and increased motivational experience for the students in terms of their learning environment, interaction with the content, workplace experience, and global interaction. These experiences are important to capture the interest and attention of the students with the aim of improving their knowledge retention. Each of the positive concept components that were identified in the initial study (Hambrock & De Villiers, 2022) are unpacked and explained in this chapter.

3.1 Student-Centered Approach

The first positive concept, student-centredness, is to foster the acquisition of knowledge and skills of students. This includes the development of character, of progressive views, and of scientific vision in order to support commitment to the upholding of national—and on some levels international —aspirations and culture heritage. Students who are being trained as competent professionals are expected to excel in their careers and to enhance the image of their profession. These are important goals for universities and other educational institutions.

The student-centred approach has come under criticism (Bayne et al., 2020; MacKenzie et al., 2022) for its implicit deprofessionalization of teaching, its devaluing of the non-human elements involved in education, and the overvaluing of the products of the educational process—of which the learner is one additional product to be consumed in the workforce. Although we acknowlege these important arguments, some aspects of student-centredness remain important in a practical sense: students at post-secondary institutions attend because they seek to acquire skills and knowledge that will position them better in their chosen occupations as well as other aspects of their lives including their social and political experiences and for their own personal enjoyment of learning.

The importance of a student-centered pedagogy with a life-long learning and task-centered approach is described by McDonald and West (2021) as

dealing with current and future developments in the job market requires that educational programs produce lifelong learners who are equipped with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to deal with familiar and unfamiliar complex tasks in their domain. The way these programs are designed must therefore match this goal of creating learners who are able to transfer their knowledge from the learning to the professional setting. Task‐centred instructional design models such as the 4C/ID model stimulate this process by prescribing learning methods that lead to a rich knowledge base allowing for creative applications of knowledge in new and innovative settings. (McDonald & West, 2021, p. 25)

Further motivation for a student-centered approach is supported by Alessi and Trollip (2001), proponents of the constructivism approach, who maintain that designers should be creating educational environments that facilitate the construction of knowledge by students. The following principles or suggestions are typically promoted as ways to accomplish that goal (Alessi & Trollip, 2001, p. 32):

- Emphasize learning rather than teaching.

- Emphasize the action and thinking of learners rather than of teachers.

- Emphasize active learning.

- Use discovery or guided discovery approaches.

- Encourage learner construction of information and projects.

- Have a foundation in situated cognition and its associated notion of anchored instruction.

- Use cooperative or collaborative learning activities.

- Use purposeful or authentic learning activities.

- Emphasize learner choice and negotiation of goals, strategies, and evaluation methods.

- Encourage personal autonomy on the part of learners.

- Support learner reflection.

- Support learner ownership of learning and activities.

- Encourage learners to accept and reflect on the complexity of the real world.

- Use authentic tasks and activities that are personally relevant to learners

Students are usually involved in learning in different ways in formal, informal, and non-formal environments. Yet, institutions do not always offer a variety of student-centered approaches; instead, they may rely upon the practices already established within their institutions or those most comfortable for the faculty. In the behaviorist learning theory, teaching and learning depend on the teachers’ roles in classrooms or pre-set lessons designed for memorization and practicing pre-determined behaviours. However, because of pedagogical and technological advances, students can take responsibility for their own learning with the assistance of technology. For example, in a recent study on artificial intelligence in education (AIE) by Lai (2021), ‘’the instructor taught the current state of technology-based learning and assigned students to design relevant technology-based learning activities. Therefore, students have gained certain concepts of technology integrated learning and teaching.’ (p. 4).

In our technologically rich era, students should learn how to conduct efficient internet searches for knowledge and skills that they need. Kohnen and Mertens (2019) explored commonalities and themes within three different expert information-seeking professions: academic librarians, journalists, and non-fiction children’s book authors. Distinct themes of doing, knowing, and being that expert information seekers employed when encountering information emerged from the semi-structured interviews. They believe that these practices could form the basis of an information-seeking curriculum that can help address the challenges of the current online information environment (Kohnen & Mertens, 2019).

Turner et al. (2019) propose a new framework of connected reading, a model of print and digital reading comprehension that conceptualizes readers’ interactions with digital texts through encountering (the ways in which readers seek or receive digital texts), evaluating (the ways in which readers make judgments about the usefulness of digital texts), and engaging (the ways in which readers interact with and share digital texts). In light of the findings, the authors argue that it is imperative to reframe discussions about how adolescents are taught to comprehend, interact with, and curate digital texts such as webpages, e-books, multimedia, social media.

Student-centred design might also be strengthened by students having access to a professional learning community of practice according to specialist’s area. Wenger-Trayner, Wenger-Trayner, Cameron, Eryigit-Madzwamuse, and Hart (2017) describe four value-creation cycles that emerge from communities of practice:

- engaging in social learning can create immediate value such as the company of like-minded people or doing something exciting;

- this engagement can create potential value such as insights, connections or resources;

- drawing on these insights, connections or resources to change one’s practice requires much creativity and learning, and thus is viewed as generating applied value;

- to the extent that changes in practice make a difference to what really matters, social learning produces realised value (Guldberga et al., 2021).

3.1.1 Student-Centered Design

According to Alessi and Trollip (2001), students should design their own knowledge and skills. They claim that “’instruction should be the creation and use of environments in which learning is facilitated’’ (p. 7). Jonassen (2009) also states:

cognitive tools require students to think mindfully in order to use the application to represent what they know. Just as electronics specialists cannot work effectively without a proper set of meters and tools to help them diagnose and repair electronic malfunctions, students cannot work effectively at thinking without access to a set of intellectual tools to help them assemble knowledge. Students should use technologies as tools, not as tutors or repositories of information (p. 7).

Accommodating Disabilities

In many countries, public institutions are bound by law to design learning approaches to accommodate learners with disabilities, with various scenarios. Accommodations do not change the content of instruction, give students an unfair advantage, or change the skills or knowledge that a test measures. Rather, accommodations make it possible for students with learning impairments to demonstrate their learning without being hindered by their disabilities. Appropriate accommodations need to be an integral part of the normal cycle of teaching and testing—never reserved only for periods of assessment.

Accommodate Learning Preferences

Learning styles have often been used in unhelpful ways by teachers, more as a way of classifying and labelling learners, rather than in a constructive way to enrich learning experiences (Papadatou-Pastou et al., 2020). Furthermore, the complexity of learning can become simplified and trivialized whilst scholarship and research literacy within education as a profession can be dangerously compromised (Sharples et al., 2009)—particularly if learners cannot cope when having to acquire knowledge and skills in unfamiliar environments or through less preferred modalities and styles. In other words, the ‘learning styles’ philosophy may lead teachers to teach to their pupils’ intellectual strengths, leaving little opportunity for students to work on their shortcomings and develop strategies to cope with the unfamiliar or uncomfortable. Nevertheless, instructors can expose learners to materials that address various learning style preferences such as:

- Visual learners

- Auditory learners

- Kinesthetic learners

- Reading/writing learners

Papadatou-Pastou et al. (2020) mention that although learning styles (LS) have been recognized as a neuromyth, they remain a virtual truism within education: learners have preferences but should still have exposure to different styles. Learning preferences go beyond learning styles. They include different learning environments. More and more universities offer online as well as face to face classes. In many universities students can select their preferred learning environment. However, such choices were no longer available during the COVID-19 pandemic for learners at some institutions.

Self-Regulated Learning

Instructors and educators can assist students by providing a learning plan for them. This plan should include more options for students to regulate their own learning. The importance of understanding learners’ perceptions before introducing new technologies or approaches environments is vital (Geertshuis, & Qian, 2020; Lai, 2021). The students input and feedback can help to ensure a successful switch from teacher-regulated learning to students making the decisions of when and what to study.

Performance

Instructors and educators have to check and mark assessments and set up exams to measure students’ learning. Large scale international evaluation studies such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) are adopted by developed countries because they provide high-quality data that support educational reform. They also provide data that identify student performance levels that can be compared to counterparts in countries with similar or different levels of development. These evaluation studies aim to assess the quality of an educational system intended to prepare students for the future by linking research, policy, and practice. They are based on the idea of “opportunity to learn,” and explore the links between the intended curriculum (what the policy requires), the implemented curriculum (what the school teaches), and the achieved curriculum (what the student learns) (Alharbi et al., 2020; Holmlunda & Sund, 2008). Although assessment practices such as PISA are available, in most educational institutions the performance of students is still measured by formative and summative assessments and might be highly unique to individual institutional, social, political, and economic contexts. The students are taught to take tests or examinations within their local institutions. The question remains if either the locally developed or internationally recognized tests accurately reflect the students’ knowledge and performance.

Reflections

Reflection on a past learning unit is not always a common practice in most universities and should become part of the course design process. Many tools are available in the market for this exercise. Faculty and administrators may lack training, knowledge, and/or experience in reflective practice. In such cases, learners are unlikely to observe reflective behaviour because of lack of modeling. Unfortunately, researchers have found that institutionally implemented learning technologies are seldom adopted or are underused by academic staff (Geertshuis & Qian, 2020).

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is included in challenge-based learning (CBL). CBL is an engaging multidisciplinary approach to teaching and learning that encourages students to leverage the technology they use in their daily lives to solve real-world problems. CBL is collaborative and hands-on, asking students to work with peers, teachers, and experts in their communities and around the world to ask good questions, develop deeper subject area knowledge, accept and solve challenges, take action, and share their experience (Nichols, 2016; Nichols & Cator, 2008; Leijon et al., 2021).

Reasoning

Many studies have identified the importance of learner perspectives and reasoning for enhancing and developing their learning performance (Deci, & Ryan, 2000; Tapingkae, et al., 2020). Researchers have attempted to infer and predict students’ learning performance by analyzing the students’ perspectives to enhance learner engagement and student motivation (Davies et al., 2013).

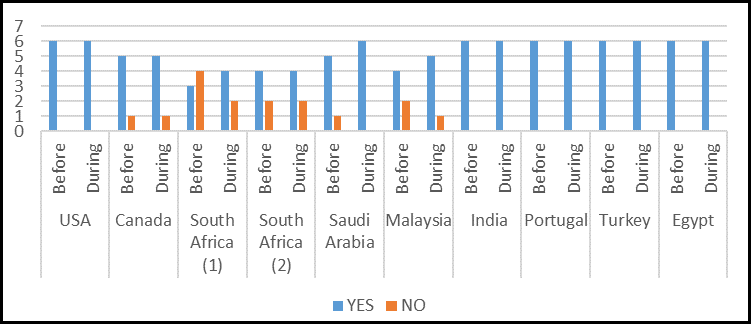

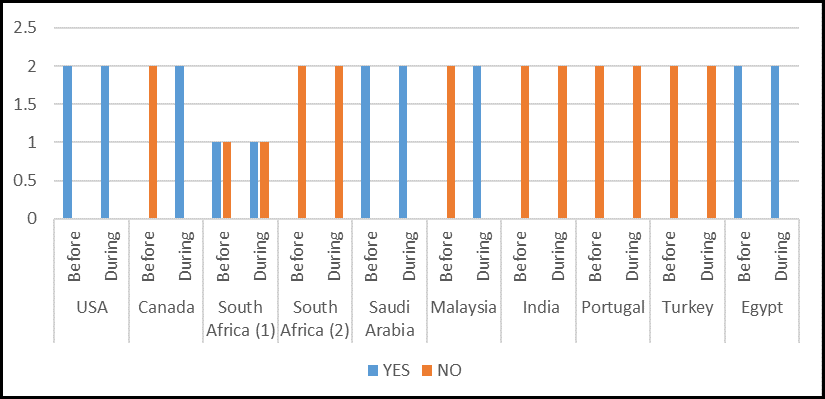

A combination of the feedback on practicing a student-centered approach from the participating countries is reflected in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1

Student-centred approach

Figure 3.1 contains information about the teaching approach in the participating countries. According to the data collected before and during the COVID-19 pandemic most countries were already focusing on a student-centered approach. However, there was a mentionable increase of student-centred learning in the institutions from South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia during the pandemic. The students in these countries had to become more reliant on their own capacity and on technology during the pandemic as classes moved from face-to-face to online learning.

3.2 Globalization

Due to a massive increase in trade and cultural exchange, the world is becoming increasingly interconnected as a result of globalization. Globalization has increased the production of goods and services and is characterized by the endless mobility of communities. Castles and Davidson (2001) refer to the increasing contact and exchange of information across cultures. This mobility of citizenship not only affects people’s perceptions of day-to-day life but also the way they interact with one other internationally. These shifting perceptions may have appealing impacts on teaching and learning. Contrastingly, Soysal (1994) describes globalization as a form of humanistic capitalism and a source of changes in views of political and ethnic issues.

When exponential growth in the analyses of globalization began to suggest that there was a global reconstruction of social, economic, and political relations, the discourse of globalization became popularized in academic and non-academic circles (Urry, 1990). Among all the changes in mobility, globalization is perhaps the most impactful. It has led to the adaptation of learning policies globally. Although change happens at different rates, its effects are global. Even though national indentures still exist, corporate capitalism now dominates economic activity world-wide. Jarvis, Holford, and Griffith (2003) define globalization as a social process in which limitations of geography on social and cultural arrangements recede and in which people become increasingly aware that they are receding. Thus, educational technology research should include theoretical, intellectual, and multidisciplinary global perspectives, given that technologies have a reciprocal relationship with mobility and globalization. However, seamless learning research is about more than technology; it is also about the dynamics of social and educational lifestyles.

For global education, it is necessary to include information about the relationship between countries and people. This information prepares individuals to understand and, potentially, interact with other people and their cultures (Altun, 2017). Anderson (1997) and Altun (2017) describe global education as a method to better prepare human and global citizenship and to make changes to the social content of education. Frequently repeated concepts in global education are:

- Attitude [attitudes towards what?]

- Information [cultural, political, geographic, demographic?]

- Talents [what kind? Why?]

3.2.1 Global Perspective

Global education is to have knowledge about problems and issues that are beyond borders. It refers to having a good knowledge of systems, ecology, culture, economic, politics and technology. Through the development of a global perspective, a learner gains an awareness and understanding of the issues and problems of the people in the world from a variety of perspectives. It also includes awareness of global events generally, experiencing different ways of thinking and knowing; thus, the learners is able to develop and articulate better informed opinions (Altun, 2017; Tye, 1990).

Another aspect of global education is the global citizenship education (GCED) which should become more integrated into the higher education curriculum. The aim of GCED is to be aware of global systems as mentioned in the previous paragraph and also cultivating respect and belonging to a common humanity. Helping learners to make responsible decisions and “to become proactive contributors to a more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive and secure world” (United Nations, 2020, p.1).

3.2.2 Virtual International Classroom

Communicating and working collaboratively with students via virtual classrooms is another approach which has evolved from globalization and technology. According to Lock (2015) “Students and educators are better positioned to work with other students and experts in new and meaningful ways at anytime and anywhere in the world. The challenge is how to design and facilitate authentic collaborative learning in the global classroom that engages students” (Lock, 2015, p.137).

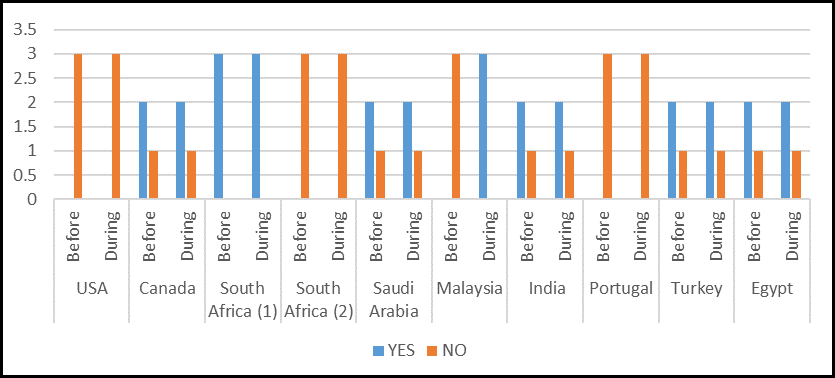

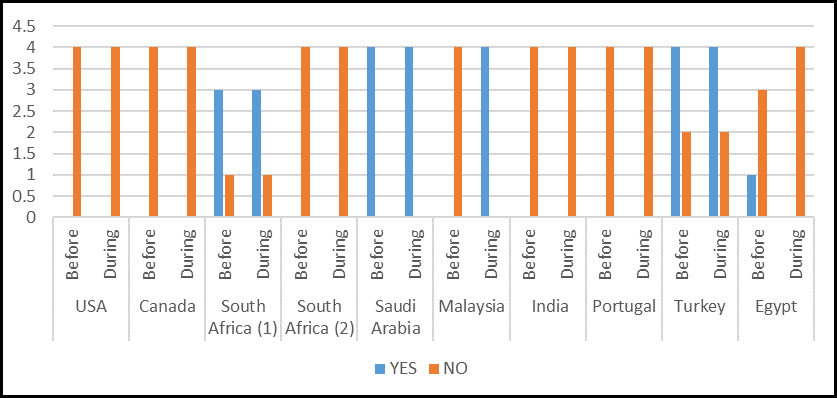

In Figure 3.2 the global or international connections before and during the pandemic mostly either continued or were never part of the actual student experiences. The three institutions that did not focus much on global connections before and during the pandemic were in the USA, South Africa (institution #2) and Portugal.

Figure 3.2

Globalization

South Africa, institution #1 maintained its global connections before and during COVID-19 is. The institututions from Canada, Saudi Arabia, India, Turkey and Egypt continued with their global approach before and during the pandemic in the sense that some courses included global interaction and some continued to not include global interaction.

3.3 Practical Experience

In a need to differentiate a temporary shift in teaching modality due to the COVID-19 pandemic from the typical online learning instruction, the term, ‘emergency remote teaching’, has emerged (Minsun & Kasey, 2021). Minsun and Kasey write that their findings:

highlighted that the participants’ experiences relating to the quality of learning, academic interest, and performance seemed to vary significantly depending on respective course instructors. This is a critical and pressing point for us to ponder. Previous research points out the quality of online learning and student success depend on proper instructor practice, instructor training and preparation to teach in an online environment, and carefully and effectively designed online courses. (p. 982)

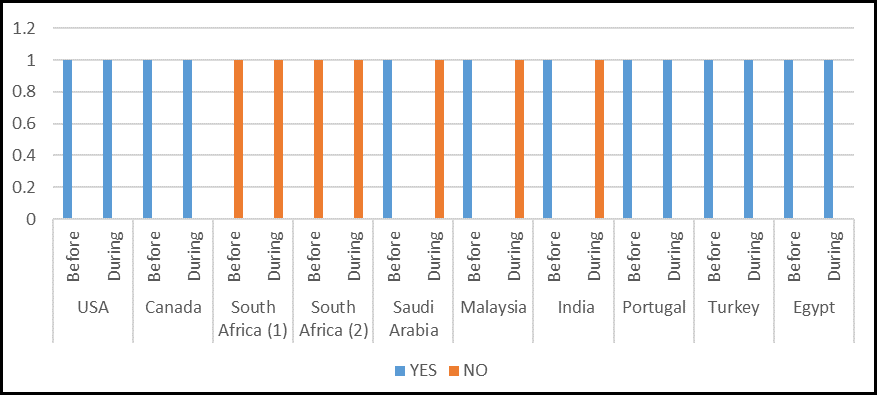

In Figure 3.3, practical experiences are included in the institutions’ curricula before and during COVID-19. The institutions in Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and India were unable to continue with practical experiences and both campuses in South Africa had omitted practical experiences in the courses.

Figure 3.3

Practical experience

3.4 Preparation for Future

A university education offers opportunities for personal growth, increased self-esteem, enhance literacy and numeracy skills, and advance problem-solving and critical thinking skills. Students gain exposure to new ideas, social and cultural diversity, and expanded worldviews. However, a significant aim of many universities is to prepare their students for the world of work (Carter et al., 2020; Abbott, 2014). The students need to be prepared for the future in a highly competitive world with challenges one could not have dreamed of even just a few years ago (Wagner & Dintersmith, 2015). This means that Universities need to adjust and transition more rapidly (Mpungose, 2020). Students need to know the world out there even before they leave the “safe walls” of higher education institutions (Box, 2005). Seamless learning can provide an opportunity to include real life experiences while the students are still studying (Looi et al., 2010).

3.5 Real-Time Interaction

The seamless approach offers students and instructors more opportunities to continue the conversation they started in class along with relevant and timely responses (Koile & Singer, 2006; Sharples et al., 2009). Immediate feedback needs to be provided to the student by the instructor or vice-versa (Van der Kleij, 2008). Students can be connected and work collaboratively in and outside the classroom. According to Palloff and Pratt (2010), Nokes-Malach et al. (2015), and Kong and Song (2014), interactive classes are possible in a seamless learning class since the pedagogy allows for activities that students can do on their own or can share with peers. In a study by Yakovleva and Yakovlev (2014), the negative experiences and challenges shared by their participants included the struggle to remain motivated, the disruption in learning, a lack of communication and feedback, a difficulty to foster creativity, and insufficient workload adjustment. In another study, participants asserted that the delayed internships and cancelled hands-on experiences, such as laboratory classes and service learning, negatively impacted students’ continued education or career advancement (Minsun & Kasey, 2021).

3.5.1 Connectedness in and Outside the Classroom

The results of a study by Boardman et al. (2021) showed that the feeling of connectedness from participants towards classmates had decreased after switching to emergency online learning. However, they felt more connected to their professors after the switch occurred. Also, the students felt that the availability of the professors had decreased after the switch.

3.5.2 Interactive Classes

Similar to the above category (3.5.1), utilizing webcam and microphone technology may help students to feel more connected to their peers and their professors. Participants from the institutions included in this study reported learners feeling more connected to their peers when these technologies were utilized to increase interaction. Students may also feel more connected to their professors when they reach out to talk to them outside of class. Limiting interactions to only lesson plans may result in students feeling disconnected and unimportant to their professors. This disconnect may be one of the reasons for lowered motivation and communication in students. More genuine interactions may persuade students to be more present in classes and give them the confidence to participate more openly (Boardman et al., 2021).

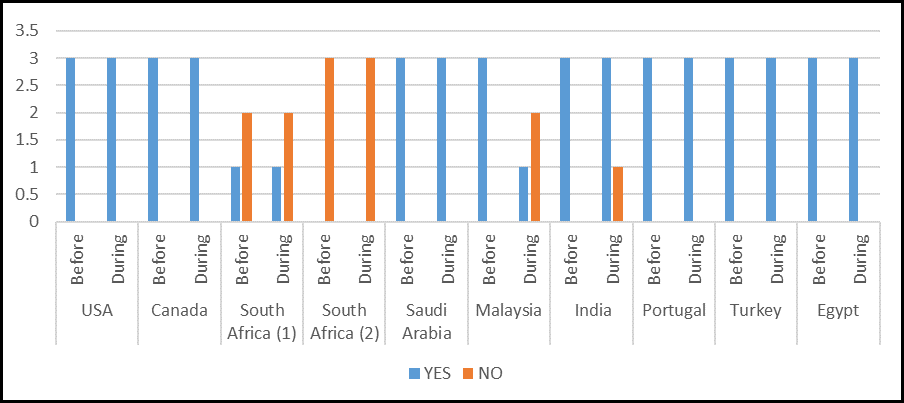

Figure 3.4

Real-time interaction

Whilst most of the participants from institutions included in this study continued indicated positive interaction between the students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Most participants indicated that their institutions continued as before. It does, however, seem that the institution in Malaysia and India had a steep decrease in real-time interaction. This may be due to the limited access to technology by the students.

3.6 Remote Access

For seamless learning to be implemented successfully, access to the learning content and contact with lecturers as well as other students is important. Remote access had not been considered a high priority prior to the COVID-19 pandemic because university classes of traditional universities were not focusing on teaching remotely. This changed dramatically when the pandemic hit and traditional face to face classes had to be taught remotely.

Many instructors attempted to offer same lectures and the same quality as in the pre-pandemic classroom and were most probably approximating their pedagogical goals in most cases; however, there were several challenges that complicated remote access to remote learning. Firstly, not all students had access to technology for remote learning. Secondly, the model of remote learning was not adequately taking the students’ needs and contexts into account. The remote learning model was flawed because the instructors were often not prepared for the “technology heavy” environment and often lost valuable time trying to figure out what to do. Furthermore, they lacked preparation for changing the format from a lecturer-centered class to a student-centered class. The advantage of remote access can, however, open new avenues for learning which became apparent during the pandemic.

3.6.1 No Time Barriers

As populations became locked down during the pandemic, less time was needed for travel resulting in more time for preparation and/or doing homework. Learning could continue before and after class time; one might say that learning could extend more easily across contexts that were, prior to the pandemic, more segmented. Instead of relying on face-to-face interaction for collaboration and cooperation, instructors and learners made use of an array of technologies. For example, several services provided by Google Workspace (formerly Google Suite) (Google, n.d., c) a package of integrated word processing, document collaboration, email, and online storage services, were employed throughout the CoP activities. Google Docs (Google, n.d., b), an online word processing application embedded in Google Drive (Google, n.d., a), has been described as a useful tool for collaborative work for university students with perceived potential for use by researcher populations. Google Docs allows for concurrent users to work on the same paper in real time and serves as an archive for previous versions stored online. For many people working and studying remotely, the use of Google Docs and other software suites allowed each member to contribute to meeting minutes, protocol development, ethics submissions, and the various phases of manuscript development (Embrett et al., 2021).

3.6.2 No Space Barriers

Throughout online collaborative activities, group meetings began to include dedicated time for routine check-ins. Meetings created space for members to clarify objectives, identify challenges or methodological tensions, and show-and-share expertise by peer mentors. As a result, both expertise and support became more fluid and interchangeable (Embrett et al., 2021). It became unnecessary for students to come to campus and sit in a physical class. All the while, classes could continue in spite of ravaging sicknesses around the world. Before the pandemic the seamless learning experience may have been contemplated by some professors, but during and after the pandemic many lessons were learned. Now, these lessons can contribute to the new seamless learning model.

Figure 3.5 indicates that within the institutions in the USA and Saudi Arabia, students already had remote access before COVID-19 and access continued during COVID-19. For the institutions in Canada, Malaysia, and Portugal, students had remote access during COVID-19, but not necessarily before COVID-19. For the institutions in countries such as South Africa (institution #1) and Egypt students had remote access before COVID-19, but during COVID-19 learners had difficulties accessing the internet particularly when their geographic location lacked satellite coverage. The institutions in India and Turkey indicated having limited remote access before COVID-19, but increased access during COVID-19. Similarly, South Africa (institution #2) had no remote access before COVID-19 and experienced increased access during COVID-19.

Figure 3.5

Remote access

3.7 Research Opportunities

3.7.1 Increased Research Output

Regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic, remote collaboration is helpful to equip research teams with tools and capacities for effectively and productively thinking together while working apart. International collaboration can be a significant source for expanding scientific inquiry and discovery. Remote collaboration provides an opportunity for researchers to create and maintain international collaborations. Refinement of best practices in international remote collaboration methods and outcomes is required to optimize participation and impact (Embrett et al., 2021).

3.7.2 Conference Sharing and Future Research Data Base

Future research may include recording a more detailed report of the best and the worst interactions that occurred during the switch to online learning during the COVID-19 emergency. Overall, participants in this study reported feeling higher levels of connectedness when face-to-face interactions occurred, even through webcams and virtual meetings. Extended office hours utilizing such technologies were used to allow students to seek out connections with professors in order to ask questions privately and collectively. Using online technologies students can still participate actively in their classes to better understand course content and succeed academically. Key learnings and recommendations based on this research suggest that instructors:

- have opportunities for students to work together in discussion and group projects;

- create a presence for your students by using tools such as Zoom that allow for an increased use of video and audio exchange;

- create opportunities for casual discussions between students, simulating conversations they would normally have at the beginning and end of an in-person class;

- reach out individually to students to check in; and

- extend office hours utilizing web-based technology such as Zoom to allow students to seek out connections with professors and ask questions privately. (Boardman et al., 2021)

3.7.3 Marketing of Institutions Innovative Approach

According to Korsakiene (2010), four basic steps of customer relation market (MRC) include:

- identification of company’s customers;

- differentiation of company’s customers;

- interaction with customers;

- customization of company’s behaviour.

Our research group suggests that these steps should be included in the overall course designs.

Figure 3.6

Research opportunities

Considering the data of all the positive concepts, those that were best prepared before and during COVID-19 were the institutions in USA, Canada, Saudi Arabia, India, Portugal, Turkey, Egypt and South Africa (institution #1). The institutions that struggled included the institutions from South Africa (#2) and Malaysia. This information is valuable and prompts more research into the reasons and causes for the ongoing challenges and how such challenges can have a negative impact on the positive concepts for seamless learning opportunities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

An interesting variety of elements that were identified as positive concepts for seamless learning were discussed in this chapter. The first focus is on student-centered and self-regulated learning. This means that students need to explore more and be “spoon-fed” less. The critical thinking and personal preferences as described in this chapter also need to be accommodated in the courses. Additionally, the students’ reasoning needs to be incorporated into the design of learning experiences at the course and programme levels. Another positive aspect deserving of careful consideration includes collaborative learning opportunities for the students. Additional positive elements that would support seamless learning include providing practical experience to help prepare students for the future employment and personal growth, offering remote access to learning, and finally increasing research opportunities. Examining pedagogical practices before and during the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light a number of these elements that can shape the learning experience in positive ways. These findings may not only be used to improve the seamless learning experiences of the participating institutions, but can also guide the practices of all students, faculty, course designers, and administrators in all countries, universities, faculties to improve courses for the future.

References

Abbott, M. (2014). Preparing our graduate students for a new world. Oceanography, 27(1), 7–7. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2014.28

Alessi, M. S., & Trollip S. T. (2001). Multimedia for learning: Methods and development. Allyn & Bacon.

Alharbi, M., Almatham, K., Alsalouli, M., & Hussein, H.. (2020). Mathematics teachers’ professional traits that affect mathematical achievement for fourth-grade students according to the TIMSS 2015 results: A comparative study among Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Educational Research, 104, 101671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101671

Altun, M. (2017). What global education should focus on. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 4(1), 82-86. https://doi.org/10.23918/ijsses.v4i1p82

Anderson, L. (1997). Schooling and citizenship in a global age: An exploration of the meaning and significance of global education. Indiana University Press.

Bayne, S., Evans, P., Ewins, R., Knox, J., & Lamb, J. (2020). The Manifesto for Teaching Online. The MIT Press. https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/manifestoteachingonline/

Boardman, K., Vargas, S., Cotler, J., Burshteyn, D., & College, S. (2021). Effects of emergency online learning during COVID-19 pandemic on student performance and connectedness. Information Systems Education Journal (ISEDJ), 19(4), 23-36. https://isedj.org/2021-19/n4/ISEDJv19n4p23.html

Box, L. (2005). The great transformation in higher education—Into something rich and strange? Mozaik 2, 22-25. http://www.koed.hu/mozaik16/louk.pdf

Carter, E. W., Schutz, M. A., McMillan, E. D., & Awsumb, J. J. (2020). Preparing youth for the world of work: Educator perspectives on pre-employment transition services. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44(3), 161-173. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143420938663

Castles, S. & Davidson, A. (2001). Citizenship and migration: Globalization and the politics of belonging. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 28(2), 191-193. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol28/iss2/18

Daggett, W. R. (2017). Preparing students for their technological future. [PDF file]. International Center for Leadership in Education. https://leadered.com/wp-content/uploads/PreparingStudentsforTheirTechnologicalFuture.pdf

Davies, R. S., Dean, D. L., & Ball, N. (2013). Flipping the classroom and instructional technology integration in a college-level information systems spreadsheet course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 563-580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9305-6

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01

Embrett, M., , Liu, R., Aubrecht, A., Koval, A., & Lai, J. (2021). Thinking together, working apart: Leveraging a community of practice to facilitate productive and meaningful remote collaboration. International Journal of Health Policy Management, 10(9), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.122

Geertshuis, S., & Qian, L. (2020). The challenges we face: A professional identity analysis of learning technology implementation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1832904

Google (n.d., a). Google Docs. https://www.google.ca/docs/about/

Google (n.d., b). Google Drive: Easy and secure access to all of your content. https://www.google.com/intl/en_ca/drive/

Google (n.d., c). Google Workspace: How teams of all sizes connect, create, and collaborate. https://workspace.google.com/intl/en_ca/

Guldberga, K., Achtypi, A., D’Alonzo, L., Laskaridou, K., Milton, D., Molteni, P & Wood, R. (2021). Using the value creation framework to capture knowledge co-creation and pathways to impact in a transnational community of practice in autism education. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 44(1), 96-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1706466

De Villiers, F & Hambrock, H. (2022) Designing a seamless learning experience design (SLED) framework in higher education based on global perspectives. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning (EJEL). (in press).

Hindin, A., Morocco, C. C., Mott, E. A., & Aguilar, C. M. (2007). More than just a group: Teacher collaboration and learning in the workplace. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 13(4), 349-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600701391911

Holmlunda, H. & Sund, K,. (2008). Is the gender gap in school performance affected by the sex of the teacher? Labour Economics, 15(1), 37-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2006.12.002

Jarvis, P., Holford, J., & Griffin, C. (2003). The theory and practice of learning (Vol. 2). Kogan Page Limited.

Jonassen, D. H. (2009). Technology as cognitive tools: Learners as designers. [PDF file]. ITForum Paper #1. http://tecfa.unige.ch/tecfa/maltt/cofor-1/textes/jonassen_2005_cognitive_tools.pdf

Kapczynski, M. (2008). The access to knowledge mobilization and the new politics of intellectual property. The Yale Law Journal, 117(5), 804-885. https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/642_y36bb3ab.pdf

Karasheva, Z., Amirova, A., Ageyeva, L., Jazdykbayeva , M., & Uaidullakyzy , E. (2021). Preparation of future specialists for the formation of educational communication skills for elementary school children. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 13(3), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v13i3.5954

Kohnen, A., M. & Mertens, G., E. ( 2019). “I’m always kind of double-checking”: Exploring the information-seeking identities of expert generalists. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(3), 273-437. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.245

Koile, K., & Singer, D. (2006, April). Development of a tablet-pc-based system to increase instructor-student classroom interactions and student learning. In Proc. of Workshop on the Impact of Pen-Based Technology on Education (WIPTE’06).

Kong, S. C., & Song, Y. (2014). The impact of a principle-based pedagogical design on inquiry-based learning in a seamless learning environment in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 17(2), 127-141 https://eric.ed.gov/?redir=http%3a%2f%2fwww.ifets.info%2f

Korsakiene, R. (2010). The innovative approach to relationships with customers. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 10(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.3846/1611-1699.2009.10.53-60

Lai, C.-L. (2021). Exploring University Students’ Preferences for AI-Assisted Learning Environment: A Drawing Analysis with Activity Theory Framework. Educational Technology & Society, 24(4), 1-15. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48629241

Leijon, M., Gudmundsson, P., Staaf, P., & Christersson, C. (2021). Challenge based learning in higher education– A systematic literature review. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1892503

Lock, J. V. (2015). Designing learning to engage students in the global classroom. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1892503

Looi, C. K., Seow, P., Zhang, B., So, H. J., Chen, W., & Wong, L. H. (2010). Leveraging mobile technology for sustainable seamless learning: a research agenda. British journal of educational technology, 41(2), 154-169.

MacKenzie, A., Bacalja, A., Annamali, D., Panaretou, A., Girme, P., Cutajar, M., Abegglen, S., Evens, M., Neuhaus, F., Wilson, K., Psarikidou, K., Koole, M., Hrastinski, S., Sturm, S., Adachi, C., Schnaider, K., Bozkurt, A., Rapanta, C., Themelis, C., … Gourlay, L. (2022). Dissolving the dichotomies between online and campus-based teaching: A collective response to the manifesto for teaching online. Postdigital Science and Education 4(2), 271–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00259-z

McDonald, J., K. & West, R., E. (2021). Design for learning: Principles, processes, and praxis (Vol. 1). EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/id

Minsun, H. & Kasey, H. (2021). Needs a little TLC: examining college students’ emergency remote teaching and learning experiences during COVID-19. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(7), 973-986. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1847261

Mpungose, C. B. (2020). Emergent transition from face-to-face to online learning in a South African University in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00603-x

Nichols, M. C. (2016). Challenge based learning (user guide). Digital Promise. https://www.challengebasedlearning.org/toolkit/

Nichols, M., & Cator, K. (2008). Challenge based learning white paper. Apple, Inc. https://www.challengebasedlearning.org/

Nokes-Malach, T. J., Richey, J. E., & Gadgil, S. (2015). When is it better to learn together? Insights from research on collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 27(4), 645-656. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s10648-015-9312-8

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2010). Collaborating online: Learning together in community (Vol. 32). John Wiley & Sons.

Papadatou-Pastou, M., Touloumakos, A., Koutouveli, C., & Barrable, A. (2020). The learning styles neuromyth: when the same term. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36, 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00485-2

Saura, J. R. (2021). Using data sciences in digital marketing: Framework, methods, and performance metrics. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 6(2), 92-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2020.08.001

Sharples, M., Arnedillo-Sánchez, I., Milrad, M., & Vavoula, G. (2009). Mobile learning. In Technology-enhanced learning (pp. 233-249). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9827-7_14

Siemens, G. & Tittenberger, P. (2009). Handbook of emerging technologies for learning. University of Manitoba. http://elearnspace.org/Articles/HETL.pdf

Soysal, Y. (1994). Limits of citizenship: Migrants and postnational membership in Europe. Chicago University Press.

Tapingkae, P., Panjaburee, P., Hwang, G. J., & Srisawasdi, N. (2020). Effects of a formative assessment-based contextual gaming approach on students’ digital citizenship behaviours, learning motivations, and perceptions. Computers & Education, 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103998

Turner, K., H. Hicks, T. & Zucker, L. (2019). Connected reading: A framework for understanding how adolescents encounter, evaluate, and engage with texts in the digital age. Reading Research Quartely, 55(2), 291-309. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.271

Tye, B. (1990). Schooling in America today: Potential for global studies. In K. Tye, Global education: From thought to action (pp. 36–48). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze. Sage Publications.

United Nations (2022). Global citizenship education. https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/page/global-citizenship-education

Van der Kleij, F. M., Feskens, R. C., & Eggen, T. J. (2015). Effects of feedback in a computer-based learning environment on students’ learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 475-511. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654314564881

Wagner, T., & Dintersmith, T. (2015). Most likely to succeed: Preparing our kids for the innovation era. Simon and Schuster.

Wenger-Trayner, B., E. Wenger-Trayner, J. Cameron, S. Eryigyit-Madzamuse, and A. Hart. (2017). Boundaries and boundary objects: An evaluation framework for mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1558689817732225

Yakovleva, N. O., & Yakovlev, E. V. (2014). Interactive teaching methods in contemporary higher education. Pacific Science Review, 16(2), 75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscr.2014.08.016