Chapter 6: Design Concepts of Seamless Learning

Rafidah Abd Karim and Gülsün Kurubacak

Introduction

Seamless learning in remote areas, collaborative learning in public spaces, and interactions with the environment and artefacts across time, context, and physical or virtual locations mediated by technology all take place in a seamless learning environment (Sharples, 2006, Chan et al., 2006). According to Hambrock et al. (2020), the concept of seamless learning are like describing an envisioned ‘continuous and (cross-) contextual’ learning and support process, distinguishing a design paradigm within the broader domain of learning and instructional design and exemplifying the organizational change of interweaving formal and non-formal learning, to describe a specific type of learning environment, to label specific and concrete learning scenarios, and to describe how mobile and ubiquitous technology can influence and change the way we learn. This chapter explores several aspects to be considered for designing a successful seamless learning experience. These aspects needed are application of knowledge, assessment, curriculum and design, feasibility, implementation and learning strategies which are deliberated as a design concept for seamless learning. Here, we discuss the aspects needed from the survey data analysis. The survey data is designed with both closed-ended and open-ended questions. There were eight respondents involved who mostly had extensive experience within educational technology from eight different countries; Canada, Egypt, USA, Spain, South Africa, Turkey, Malaysia and India correspondingly. This chapter aims to gain perceptions into technology educators’ at tertiary institutions that determine the seamless learning design concepts.

6.1 Application of Knowledge

Knowledge application is when available knowledge is used to make decisions and perform tasks through direction and routines. Both direction and procedures apply to both implicit and explicit knowledge (Becerra-Fernandez & Sabherwal, 2010). It is not necessary for the person implementing the knowledge to understand it. The application of knowledge is substantial for giving students the ability to search, analyse, and evaluate material can assist them in making their own connections. Connecting newly acquired knowledge with previously acquired background information aids in the development of greater meaning and enhanced engagement. For this aspect, students must be able to apply knowledge. Students can apply their knowledge to problems and situations outside the classroom. For example, students can do a role play and taking on “various roles” like a lawyer, prosecutor, judge, or compile a marketing plan. There is also the potential to integrate practice and work placement learning into the classroom. There are several activities that can help students to apply their knowledge such as maximizing the early learning experience for transfer, activate prior knowledge, deliberate practice, simulations, group learning and analogies and metaphors. Kuh (2008) suggested that teaching students how to use their knowledge and talents to help others or serve the public good is one extremely effective technique for developing these abilities across disciplines.

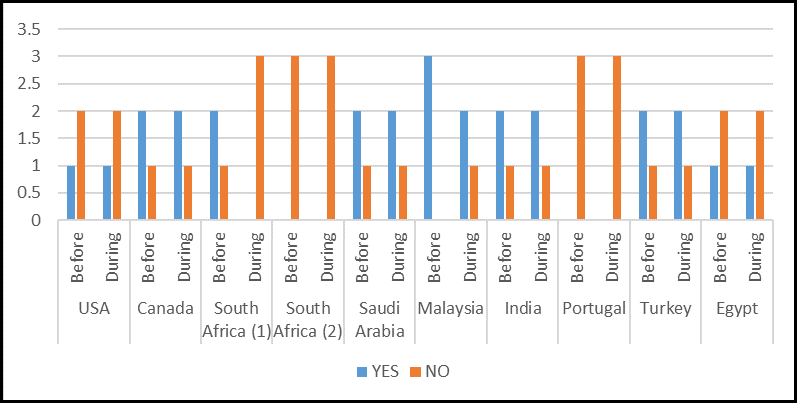

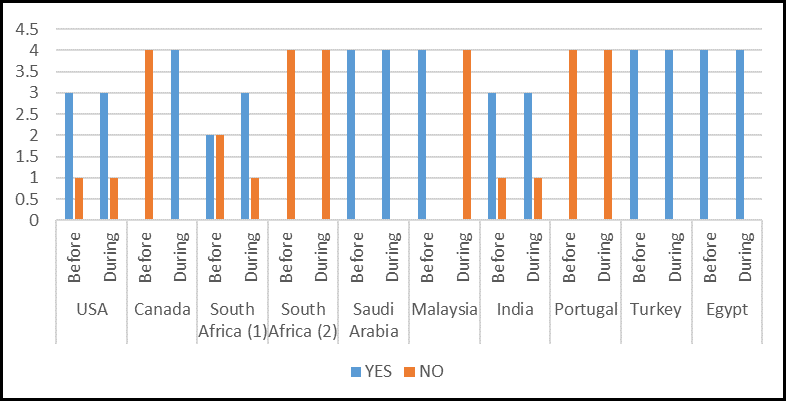

Figure 6.1 reveals the application of knowledge aspect practiced for seamless learning concepts on the campus per country. From the table, the Malaysian respondent answered (Yes= 3) which demonstrates that the institution dynamically practiced seamless learning design concept before the COVID-19 pandemic and decreased to (Yes=2) during the COVID-19 pandemic while both Portugal and South Africa (2) institutions answered the highest number (No=3) which showed both countries do not practice the application of knowledge in the teaching approach before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. India institution answered (Yes=1; No =1) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Egypt institution shows the lowest number of responses (Yes=1) for the application of knowledge before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, USA country showed the response (Yes=1) for this aspect before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey institutions had a parallel response (Yes =2; No=1) for the application of knowledge practice in the teaching approach before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.1

Application of knowledge aspect practiced for seamless learning on the campus per country

6.2 Assessment

Fenton (1996) described assessment as the collection of relevant information that may be relied on for making decisions. More recently, Conrad and Openo (2018) noted a simplified definition that assessment “provides evidence of the outcome in any outcomes-based approach to education” (p. 5). According to Davies (2000), assessment for learning is ongoing, and requires deep involvement on the part of the learner in clarifying outcomes, monitoring on-going learning, collecting evidence, and presenting evidence of learning to others. Brown (1990) said that assessment refers to a related series of measures used to determine a complex attribute of an individual or group of individuals. He further suggested that assessment includes four basic components: 1) Measuring improvement over time 2) Motivating students to study 3) Evaluating the teaching methods 4) Ranking the students’ capabilities in relation to the whole group evaluation.

Generally, there is a need for matching assessment strategy with learning outcomes. The strategies can be divided into two categories of assessment which are the indirect assessment and the direct assessment. Direct measurements such as written work, projects, performances or presentations, portfolios and assignments are most successful when they are also course-embedded, which implies that the student’s work counts towards the grade. According to Suskie (2009):

A portfolio is compelling evidence of what a student has learned. It assembles in one place evidence of many kinds of learning and skills. It encourages students, faculty, and staff to examine student learning holistically seeing how learning comes together rather than through compartmentalized skills and knowledge. It shows not only the outcome of a course or program but also how the student has grown as a learner. It is thus a richer record than test scores, rubrics, and grades alone (p. 204).

Most assessment data studies demonstrate that if the student work is also incorporated in the grading criteria, the student takes the activity more seriously. While indirect measurements like assignment of course grades, focus group, and interviews can be valuable, learning assessment must rely mostly on direct measures. Thus, assessment strategies include that “different types of assessment methods must be explored to complement different methods of learning. It is also suggested to have a more proactive use of technology and to use apps for measuring progress. The choice of assessment strategies is in favour of the instructors whether they want a continuous assessment and feedback or after relevant time pass, and compare it with a baseline.

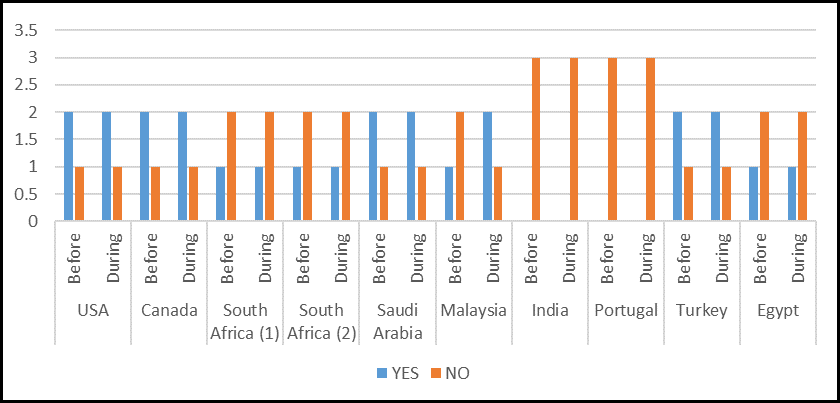

Regarding the assessment aspect, Figure 6.2 shows that the application of the assessment on the campus per country. Most of the countries reveals that they employ the assessment for seamless learning approach in both situations. Saudi Arabia, USA, Canada and Turkey institutions answered (Yes= 2; No 1) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic for the assessment aspect applied for seamless learning concept. South Africa (1) and South Africa ( 2) institutions also applied the concept (Yes= 1; No=2) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Malaysia institution illustrate an increase of number from (Yes=1) to (Yes=2) for the application of seamless learning in the assessment aspect before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Egypt institution showed an unchanged number of frequency (Yes=1) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the findings show India and Portugal institutions do not apply the assessment through seamless concept before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.2

Assessment aspect applied for seamless learning on the campus per country

6.3 Curriculum and Design

Curriculum design is one of several basic talents required for professional success for newcomers to the instructional design sector (Burning Glass, 2022). It is concerned with much more than learning materials. In one sense, curriculum design is creating a holistic plan for the environments where learning happens. This includes considering the physical, digital, social, and psychological variables that define the spaces and settings in which people learn. (American Educational Research Association, 2022). A Learning Module is a well-organized collection of content that is presented in a logical order. Donnelly and Fitzmaurice (2005) emphasized three fundamentals involved in the process of constructively aligning the module:

- Defining the learning outcomes

- Selecting the learning and teaching methods that can lead to achievement of outcomes

- Assessing student learning outcomes.

In this aspect, an instructional design approach also must be considered for implementing the seamless learning concepts. Branch and Kopcha (2014) say that “instructional design is intended to be an iterative process of planning outcomes, selecting effective strategies for teaching and learning, choosing relevant technologies, identifying educational media and measuring performance” (Branch & Kopcha, 2014, p. 77). The examples of instructional design models that can be applied in the learning design are like ADDIE, Assure, Kemp Design Model, TPACK, Robert Gagné’s Taxonomy of Learning, Bloom’s Taxonomy and Flipped Classroom. Furthermore, concerns were regarding more curriculum changes those different designers are needed and not all modules can implement seamless learning. Regarding the design, it was suggested to use “instructional design”, “effective and conscious design”, a “question-answer model” (6:23) and an initial steps-design phase”. For this, you need educational experts. Other recommendations were the use of AI tools, and that the module must be redesigned and not merely be uploaded to an online platform.

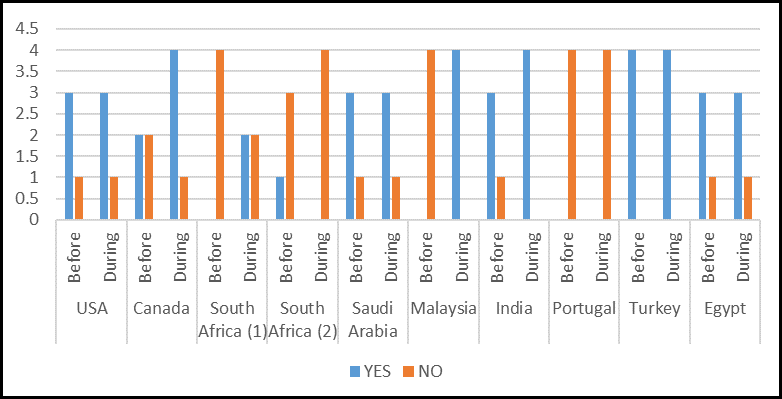

Figure 6.3 shows that the curriculum and design aspect included for seamless learning concept. The respondent from Turkey answered the highest number (Yes =4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic followed by Canada institution which showed an increased number from (Yes= 2) to (Yes=4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. USA and Saudi Arabia and Egypt institutions indicated the same results (Yes=3) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and the answer (No=1) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Malaysia respondent answered (No= 4) before the COVID-19 pandemic and (Yes=4) during COVID-19 pandemic for the curriculum and design implementation for seamless learning concept. India institution showed an increase from (Yes=3) to (Yes=4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For South Africa (1), the data shows the curriculum design included for seamless learning concept was improved considerably from (Yes=0) to ( Yes= 2) whereas South Africa (2) institution only indicates ( Yes=1) for this aspect included before the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the data shown that Portugal institution has not included the curriculum and design aspect included for seamless learning concept before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.3

Curriculum and design aspect included for seamless learning on the campus per country

6.4 Feasibility

The feasibility of assessments is concerned with practical issues such as ensuring that a location to hold the exam is available and allocating enough time for students to sit the exam. It is equally critical to keep your personal time in mind. If you have a large group of pupils submit essays, you must also allow enough time to mark them. To design a successful seamless learning, the possible questions asked were like: “Is this feasible, Do the benefits outweigh the barriers? Can the university’s servers handle the strain”, and Doesn’t all this deduce from the education itself?”. Besides, there needs to be a pilot program to resolve any mistakes and assure the project’s feasibility. A pilot study is a small feasibility study designed to test various aspects of the methods planned for a larger, more rigorous, or confirmatory investigation (Arain et al., 2010).

Gael and Ellen (2015) highlighted the main objectives of feasibility studies as listed below.

- evaluation of recruitment capability and resulting sample characteristics.

- evaluation and refinement of data collection procedures and outcome measures.

- evaluation of the acceptability and suitability of the intervention and study procedures.

- evaluation of the resources and ability to manage and implement the study and intervention.

- preliminary evaluation of participant responses to intervention.

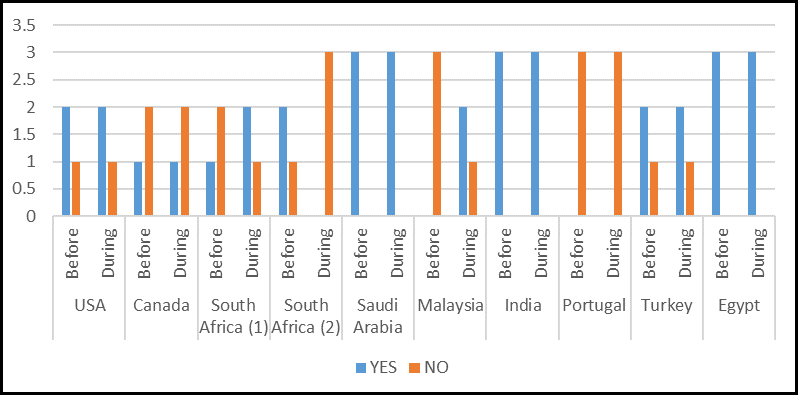

Based on Figure 5.4, the data shows the feasibility aspect available for seamless learning on the campus. The most significant results revealed that Saudi Arabia, India, and Egypt institutions responded (Yes=3) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. These results described that both countries have sufficient facilities in carrying out the seamless learning concept. Malaysia respondent answered that before the COVID-19 the feasibility available is low (No=3) but it was increased to (Yes=2) during the COVID-19 pandemic. USA and Turkey institutions was found to have similar results (Yes= 2) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and (No=1) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada respondent answered (Yes=1) and (No=2) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This reveals that the feasibility aspect for seamless learning concept was decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. For South Africa (1) institution, it shows the improvement in feasibility aspect from (Yes=1) to (Yes=2) before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the pandemic whereas South Africa (2) shows an increase for no feasibility aspect was available during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, Portugal country shows no feasibility aspect available before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.4

Feasibility aspect available for seamless learning on the campus per country

6.5 Implementation

Implementation refers to “a specific set of activities designed to put into practice an activity or program” (Fixsen et al., 2005, p. 5). Regardless of the characteristics of the target audience, the type of programme, or the exact programme goals, execution is critical. Evidence for the importance of implementation has been obtained in multiple areas including education, mental health, health care, community-based initiatives, technology, industry, and management (Durlak & Dupre, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2005). The point is that quality implementation is necessary to increase the chances of being successful. In other words, “when it comes to implementation, what is worth doing, is worth doing well. For this aspect, when we are looking at class sizes, it might be a problem to implement seamless learning. One needs a plan of action and coordination as well as good technical support. Decisions must be communicated to all staff and students. Careful consideration must be given to the time of implementation.

Figure 6.5 illustrates the implementation aspect designed and practiced for seamless learning on the campus. The data shows Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt institutions had a significant result (Yes= 4). The countries had included the implementation aspect for seamless learning concept before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For USA and India countries, the results show (Yes=3) that the implementation aspect was included before the COVID-19 pandemic whereas there was no (No= 1) implementation aspect before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For Canada country, the data shows (No=4) before the COVID-19 pandemic and (Yes=4) during the COVID-19 pandemic. South Africa (1) respondent answered (Yes=2) before the COVID-19 pandemic and increased to (Yes=4) during the COVID-19 pandemic. South Africa (2) has shown the results (No=4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Malaysia country displays (Yes=4) before the COVID-19 pandemic and no implementation aspect (No= 4) during the COVID-19 pandemic for the implementation aspect of seamless learning concept. Portugal respondent said that there was no implementation for both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (No=4).

Figure 6.5

Implementation aspect designed and practiced for seamless learning on the campus per country

6.6 Learning Strategies

Oxford and Nyikos (1989) define language learning strategies as “the often-conscious steps of behaviors used by language learners to enhance the acquisition, storage, retention, recall, and use of new information” (p. 4). Memory strategies, cognitive strategies, compensatory strategies, metacognitive strategies, affective strategies, and social strategies are all said to be learning techniques (Oxford, 1990). Learning techniques drew the attention of scholars interested in second language acquisition in the 1990s (Ellis, 1994; McDonough, 1999). A strategy is helpful if “(a) the strategy relates well to the L2 task at hand, (b) the strategy fits the particular student’s learning style preference to one degree or another, and (c) the student employs the strategy effectively and links it with other relevant strategies” (Oxford, 2003, p. 8). A learning strategy, in more technical terms, is an individual’s method of organizing and employing a certain set of skills to learn content or complete other tasks more effectively and efficiently in both academic and non-academic settings. (Schumaker & Deshler, 1992). To make a seamless learning successful, some factors like connectivity, creative and unique learning opportunities, advancement of engagement and accelerated curriculum need to be emphasized and managed during the conceptualization process. A learning strategy is just an individual’s method to completing a task.

The highlighted learning strategies for modern pedagogy are implemented in educational institutions at all levels. Through these, students can supplement their understanding of the fact that to improve their learning in terms of subjects and concepts, they must not only use technologies, the internet, books, articles, projects, reports, and other reading materials, but also supplement their understanding of learning strategies. Figure 6.6 shows ten learning strategies for modern pedagogy: crossover learning, embodied learning, science, content-based learning, analytics of emotions, adaptive teaching, argumentation, incidental learning, computational learning, and stealth assessment (TeachThought, 2022).

Figure 6.6

Ten learning strategies for modern pedagogy (TeachThought, 2022)

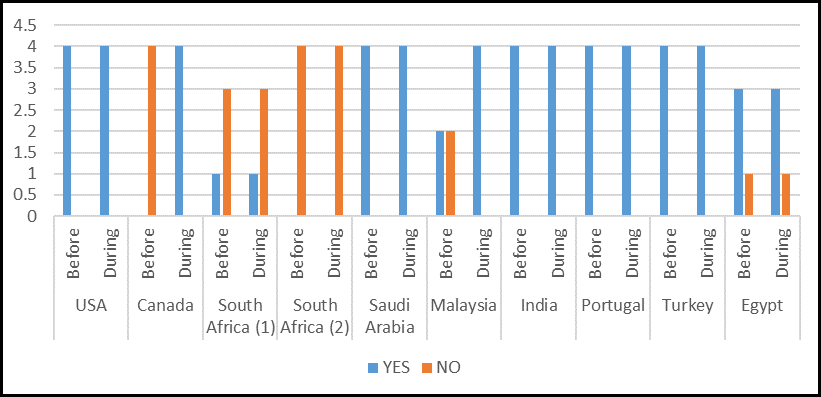

Figure 6.7 describes the learning strategies aspect implemented for seamless learning concept on the campus. USA, Saudi Arabia, India, Turkey, and Portugal countries showed the significant and similar results (Yes=4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic for learning strategies implemented in their campuses. This implies that that this country applied learning strategies before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada respondent answered (No=4) before the COVID-19 pandemic and (Yes=4) during the COVID-19 pandemic for this aspect of seamless learning concept. South Africa (2) country shows the high number for ‘No’ answer (No=4) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. South Africa (1) country revealed the answer (Yes=1; No=3) for this aspect before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Malaysia country showed an improvement in the learning strategies implementation aspect from (Yes=2) before the COVID-19 pandemic to (Yes=4) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, Egypt country showed that there were also the learning strategies implemented (Yes= 3) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6.7

Learning strategies aspect implemented for seamless learning on the campus per country

Conclusion

Today, researchers have become increasingly interested in seamless learning environments (SLE) that bridge formal and informal learning as mobile computing devices and network access become more widely available. Therefore, this chapter displays several factors to consider when designing a successful seamless learning experience such as application of knowledge, assessment, curriculum and design, feasibility, implementation and learning strategies. Based on these factors, it can be determined that several countries involved in this study appeared ready for the implementation of seamless learning concepts during the COVID-19, whereas a few countries needed more effective preparations. Several countries are also appearing to be ready with the seamless learning approach before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the seamless learning environment (SLE) can be realized if all the factors can be taken into account and all the problems and challenges for the implementation of this seamless learning concept can be overcome. Therefore, learning through both individual and collective efforts, as well as across multiple contexts (such as in-school vs after-school, formal vs informal, physical world vs. virtual reality or cyberspace) can be envisioned in future learning environments.

References

American Educational Research Association (2022). Learning Environments SIG 120. https://www.aera.net/SIG120/Learning-Environments-SIG-120

Arain, M., Campbell, M. J., Cooper, C. L., & Lancaster, G. A. (2010). What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(67), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-67

Becerra-Fernandez, I. & Sabherwal, R. (2010). Knowledge management: Systems and Processes. M.E. Sharpe.

Branch, R. M., & Kopcha, T. J. (2014). Instructional design models. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 77–87). Springer.

Brown, D. H. (1990). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. Longman.

Burning Glass (2022). Program insight. https://www.burning-glass.com/products/program-insight/

Chan, T., Roschelle, J., Hsi, S., Kinshuk, Sharples, M., Brown, T., Patton, C., Cherniavsky, J., Pea, R., Norris, C., Soloway, E., Balacheff, N., Scardamalia, M., Dillenbourg, P., Looi, C., Milrad, M., & Hoppe, U., (2006). One-to-one technology-enhanced learning: an opportunity for global research collaboration. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning Journal, 1(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793206806000032

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning: Engagement and authenticity. AU Press. https://www.aupress.ca/books/120279-assessment-strategies-for-online-learning/

Davies, A. (2000). Making Classroom Assessment Work. Connections Publishing

Donnelly, R., Fitzmaurice, M. (2005). Designing modules for learning. In G. O’Neill, S. Moore & B. McMullin (Eds.) Emerging issues in the practice of University Learning and Teaching (pp. 99-110). All Ireland Society for Higher Education (AISHE).

Durlak, J. A., & Dupre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350.

Ellis, R. (1994). A theory of instructed second language acquisition. In N. Ellis (Ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages. Academic Press.

Fenton, R. (1996). Performance assessment system development. Alaska Educational Research Journal, 2(1), 13–22.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida National Implementation Research Network.

Gael I. & Orsmond, E. S. C. (2015). The distinctive features of a feasibility study: Objectives and guiding questions. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 35(3), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1539449215578649

Hambrock, H., de Villiers, F., Rusman, E., MacCallum, K., & Arrieya, A. S. (2020). Seamless learning in higher education. Perspectives of international educators on its curriculum and implementation potential. Global research Project 2020, International Association for Mobile Learning. https://seamlesslearning.pressbooks.com

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. AAC&U.

McDonough, S. (1999). Learner strategies. Language Teaching, 32(1), 1-18. doi:10.1017/S0261444800013574

Oxford, R., & Nyikos, M. (1989). Variables affecting choice of language learning strategies by university students. Modern Language Journal, 73, 291–300.

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House Publishers.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. GALA, 1-25

Sharples, M. (2006). How can we address the conflicts between personal informal learning and traditional classroom education? In M. Sharples (Ed.), Big issues in mobile learning (pp. 21–24). LSRI, University of Nottingham.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing Student Learning: A common sense guide. Jossey-Bass.

Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (1992). Validation of learning strategy interventions for students with LD: Results of a programmatic research effort. In Y. L. Wong (Ed.), Contemporary intervention research in learning disabilities: An international perspective, (pp. 22-46). Springer-Verlag.

TeachThought (2022). What are the most innovative learning strategies for modern pedagogy? TeachThought University. https://www.teachthought.com/the-future-of-learning/innovative-strategies/