Chapter 7: Technology as a Tool for Learning: Relevance During the Pandemic

Uwe Wollin and Helga Hambrock

Introduction

Educational Technology

The use of technology in the field of education has come a long way and can be traced back to the time when tools such as abacuses were used for counting large numbers since the ancient times. For many years papyrus was used for documentation and teaching and replaced by paper made from pulp. In the pre-industrial age, enough slate was mined so slates could be used in schools all over the world (1801). Teachers would use blackboards (1890) and chalk for teaching.

As soon as the printing press (1450) AD was developed, books and posters became popular in schools and with mimeographs (1940) (for example Gestetner and Roneo machines) copies were made of exercises and notes. These were replaced by the photocopier (1959).

The first technology for multiple-choice assessment was the Army Alpha that was used to assess the IQ of military recruits for World War II.

Other technologies that were used for military training as well as in schools and universities included overhead projectors, slide projectors (1950s), radio (1925), film (1925), video (1940), ballpoint pen (1940) video tape (1951) and more recently digital cameras, video cameras, interactive whiteboard tools, document cameras, and LCD projectors. The original duplication machines were replaced by 2000 with scanners and laser printers.

Basic Computers were first introduced to education with experiments in the 1960s for learning math and spelling by Patrick Suppes and Richard Atkinson at Stanford University [i]. Personal Computers were available for education since 1980 and in 1993 the World Wide web was introduced to education (CERN, n.d.). In 1999 the Interactive whiteboard and the first laptop with Wifi was introduced. The first smartphones were available in the late 1990s and the tablet in 2010.

Learner management systems became accessible and affordable and open-source LMS platforms like Moodle (n.d.) have offered education systems for students all over the world.

Video conferencing and virtual and augmented reality have been evolving over the past ten years. These tools have become most useful during the pandemic when classes had to go online.

The actual devices and tools that can be used in education may be helpful to give students more access to knowledge but the approach on how these processes or teaching strategies will take place is important.

7.1 Teaching Strategies

Several teaching strategies have been tested over the years and the main strategies that have been found to be successful include the behaviorist pedagogical approach, the cognitivist approach, and the constructivist approach.

7.1.1 Behaviorism

During the early 20th century, behavioral experiments were conducted with animals by psychology researchers such as Pavlov, Thorndike, and Skinner. They believed that the same repetitive approach with rewards and punishments would be successful for students as well.

This approach was not accepted as sufficient after further studies were conducted in the field of the human brain and memory.

7.1.2 Cognitivism (1960s and 1970s)

The cognitivist approach considers how the human memory promotes learning. Two schools of cognitivism developed over this time and included the cognitive processes of an individual and the influence of society on the learning processes. They agree that learning is not a behavioral process but rather a mental process of the learner.

7.1.3 Constructivism and Constructionism (1980s and Further)

Constructivism is an approach that has been viewed from two perspectives that include individual constructivism (Piaget, 1957) and social-constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978).

Both share the understanding that learning is acquired by constructing their own meaning from newly acquired information. The learning can be acquired on their own from readings and experiences or from peers and society. They build the new knowledge on prior learning.

The role of the teacher changes for this approach as he or she no longer prescribes and dictates to the student but guides and facilitates the students as he/she constructs his/her knowledge.

Papert (1980) further elaborated on the constructivist perspective adding that people build knowledge most effectively when actively engaged in constructing things in the world. He early realized the potential of the computer as a tool for learning, developing the first programming tool for children (LOGO) based upon Piaget’s work. In the book Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas, Papert (1980) argues against the idea of the computer programming the child and advocates that the child should program the computer and use it as a tool for theory building.

7.1.4 Teaching Environments

Face-to-face classes, Online, Blended, Flipped, Hybrid, Hyflex, Synchronous and Asynchronous are the different types of teaching environments that can be offered to students when using educational technology.

7.2 Background

7.2.1 Pandemic and its Influence on Higher Education

During the pandemic, face-to-face classes were no longer allowed, and students had to work online with their teachers. The approach was often the same as in the traditional classroom where the teacher would talk to the students, and they would listen. This meant that a behaviorist approach was the underlying pedagogical approach and created frustration and low levels of learning as students would get screen fatigue and had no interest in the classes.

The teachers needed to re-plan their classes but did not know what to do due to very limited training on using video conferencing effectively.

This study focuses on the gaps and the challenges that the involved higher education institutions from seven countries (Canada, Malaysia, India, Portugal, Saudi-Arabia, South-Africa, and the USA) from around the globe experienced and aims at finding suggestions on how seamless learning can be implemented based on availability of technology and understanding of pedagogical approaches or methodologies.

Surveys were sent to researchers in each country and the data was collected and analyzed. The data collection and analysis process are discussed in the next section.

7.3 Data Collection

7.3.1 Open-Ended Survey Questions, Interview for More Information

Survey Design

The data collection for this technology chapter (the technology specific questions in the survey) is based upon a combination of closed-ended and open-ended survey questions. We wanted both to collect data for statistical use that could be used in a comparative analysis and get a deeper insight into additional information that the closed-ended questions might not provide us with. Thus, the data we have collected is both quantitative and qualitative data. For more on the pros and cons see Eyisy (2016). Our approach was chosen based upon the following reasoning:

- By thematizing technologies (that can comprise of many in the educational settings over four continents) under an Organizational Framework using closed-ended questions we could provide a recognizable landscape of options for the respondent to choose from. By doing so we hoped to trigger the respondent’s tacit knowledge and memory/experience with the various technologies that could be expressed in the following open-ended questions.

- The open text format in the open-ended questions would be making the respondents capable of delivering answers based upon their own knowledge, feelings and understanding. Thus, the use of first closed-ended questions followed by open-ended questions could be a tool for reflection regarding how technology, teaching culture, and theories and methodologies blend and interact – and make differences stand out.

- Using open-ended questions allows the researcher to probe deep into the respondents’ answers contrary to only using closed-ended survey questions that might limit and narrow the respondents’ answers and therefore might leave out important information about the teaching and learning environments at the respondents’ institution.

Choosing between quantitative and qualitative research methodology is not really a choice. In most disciplines in the social sciences, it is recognized that both types of research are important to a good research study. The most important are reliable and valid research results. Sutrisna (2009) argues in his complete “continuum philosophy” that the paradigms of quantitative and qualitative are in fact extremes within which research takes place (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1

Quantitative – Qualitative “continuum” in research methodology (Sutrisna, 2009, p. 9)

It is the types of data, the mode of data collection and the research direction, and goal that is the determinant for where specific research can be placed inside the continuum (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2

Research position along the quantitative –qualitative “continuum” in research methodology (Adapted from Sutrisna, 2009, p. 9)

The data collected for the technology part of the survey, both consisting of various degrees of data within the two extremes, hopefully will provide some indications of what further steps could be contributing to apply in future research.

Challenges in Data Collection

The survey was originally sent as a Microsoft Word (2022) document to the respondents by mail. Due to problems with different mail systems and different text formats we decided to place the survey in a Google Drive (n.d., a) folder for the respondents to fill out. We had several iterations as this was a fairly new environment for many respondents and we suspect that the original survey questions sheet with answers was overwritten several times with new answers as the respondents seemingly failed to save the document with a new name. After using Google Forms (n.d., b), we succeeded.

This example shows some of the challenges in data collection: users/respondents are working from different technical platforms, and new environments unfamiliar to the respondents require very clear instructions. There can also be flaws regarding the understanding of the structure and understanding of the survey.

In a future data collection, we will consider using a dedicated survey tool combined with interviews to obtain further information. The form of the interviews is still to be determined, but could be in the range of structured, semi-structured or unstructured interviews combined with group interviews.

Sample Size and Characteristics

The survey was sent out to eight respondents from six countries on four continents, and received nine completed surveys. Most of the respondents have significant experience within educational technology and only one is relatively new to this area. See chapter 7 for an elaborate description of the distribution. The initial question is:

- How can seamless learning be implemented based on availability of technology and understanding of pedagogical approaches or methodologies?

7.3.2 Data Analysis

Figures – Comparative Analysis

The technology part of the survey consists of 11 questions divided into two themes:

- Technology specific questions (1a – 4b)

- Teaching Culture (1, 1a, 1b, 1c)

As for the technology specific questions (except for question two), the first question (labeled ‘a’) is a closed-ended question offering a range of options the respondent can choose from regarding the organizational framework at the institution supporting the use of technology. The second question (labeled ‘b’) is an open-ended question offering the respondent an opportunity to elaborate further on the answers to the options in the question labeled ‘a’. The theme about teaching culture is divided into four questions of which the three first are closed-ended questions and the last open-ended.

In the following, we present the results of both the closed-ended and open-ended questions divided in the three themes (Technology Specific Questions, Teaching Culture, Theories and Methodologies). For each question the first figure shows the percentage for the total of countries, the second figure shows the distribution between each of the countries (except for Figure 7.13.), followed by the open-ended question.

For South Africa, we have answers from two campuses at the same HEI. South Africa 1 is situated in an urban area, while South Africa 2 is situated in a rural area.

7.3.4 Technology Specific Questions

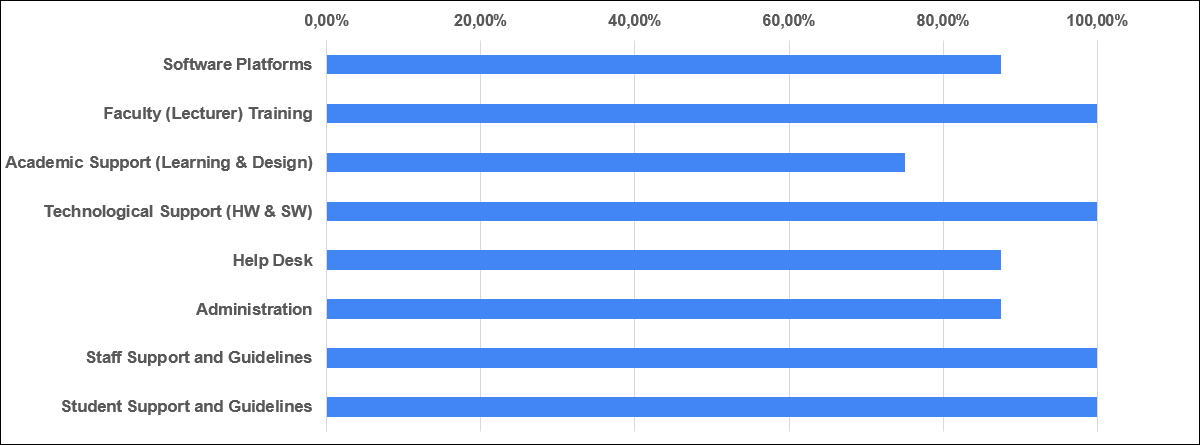

Technology-specific question 1a. Which of the following aspects are relevant and existing at your institution? Please elaborate on each of these elements in your own environment in 1b. (8 responses).

Figure 7.3

Technology specific questions 1a – organizational framework for support of technology use for the total of the countries

The answers were very similar with very few variations when it came to the organizational framework supporting the respondents’ use of technology in their institution (Figure 7.4).

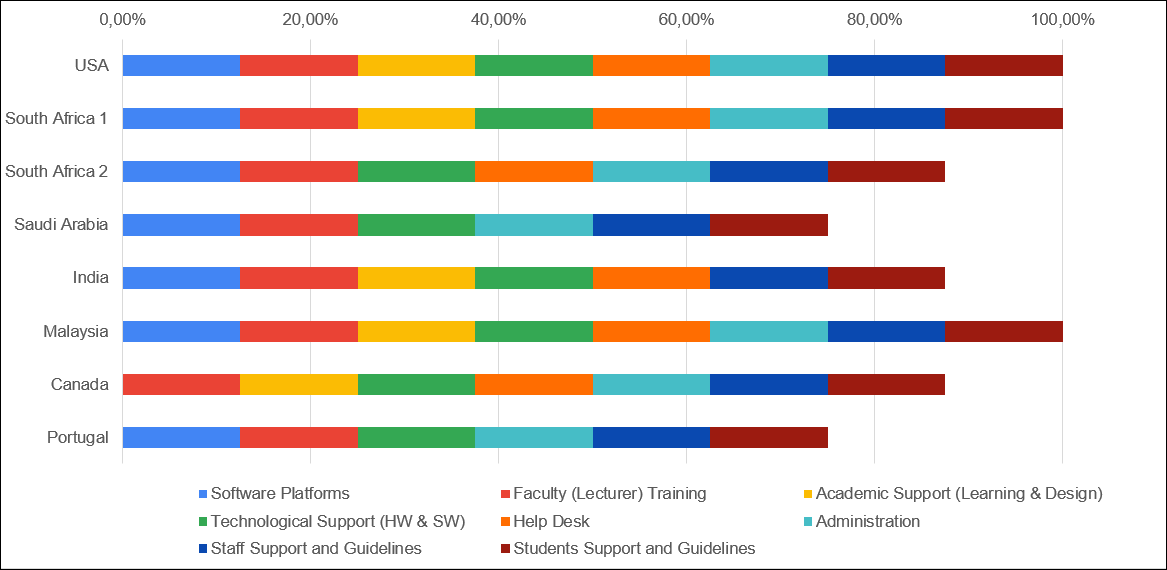

Figure 7.4

Technology specific questions 1a – organizational framework for support of technology use per country

One third (37.5%) of the respondents confirm all options are relevant and existing in their institution.

Two of the respondents answered that Help desk and Academic Support were either not relevant or existing in their institution. One respondent answered that Administration was either not relevant or existing, and one answered Software Platforms were either not relevant or existing at the institution. A follow-up on the questions revealed that at the HEI in Saudi Arabia, there is no physical Help Desk. When need for support arises the lecturer calls the technicians who then come to the classroom to fix the problem. For South Africa 2 the lack of Help Desk is because there is a physical Help Desk at the urban campus (South Africa 1), but there is still virtual help desk support for the campus situated in the rural area (South Africa 2).

The following open-ended questions provide some further information.

Technology specific question 1b: Elaborate in your own words what and how you are using the selected options in Question 1a. (7 responses).

The comments further indicate that the institutional support is well known, accessible, and being used:

“At the university there is a lot of help and support from the university side regarding Teaching and Learning.”

“Our university offers training in the form of workshops, brown bags (training session), support on FAQ, technical and LMS support.”

“We have a designated teaching and learning administrative officer in each faculty that may help the lecturers. We also have a Teaching & Learning Office that assists in all matters related. There is a designated division for creating online content but that will cost you money.”

“There is an abundance of training opportunities provided by the Center for Teaching and Learning.”

“When you have a laptop provided by the university, all the hardware is uploaded upfront. You are not supposed to add anything else if it is not approved by the ICT services. You may receive benefits for hardware every three years. We also have an entity system where lecturers receive money for academic outputs. You may use this entity money to buy computers, printers or cartridges.”

One respondent also refers directly to the COVID-19 situation:

“The [university name] offers a very wide range of supportive services to its faculty and students – it had to during the COVID 19 pandemic. It might not be perfect at this stage, but great strides have been made in this regard. I use all of the above elements, to a more or lesser extent as needed.”

Further answers indicate that there is an awareness from the university that the support does not only serve the purpose of providing help in the traditional setting of the teaching and learning situation, but also can serve a purpose of moving strategically into establishing a more consolidated online (virtual) learning and teaching environment:

“The support of the University is real because they want to create an online branch, and we are creating the conditions to implement it – since the Administration to the teachers the interest is very high.”

One respondent suggests what could be done to further promote the development of organizational support:

“Need Analysis approach would bring out what gaps exist and how these can be filled in.”

This last quoted respondent has left out the Administration option indicating that it is either not existing or relevant in the institution. As administration must exist in an educational institution the answer either indicates that the administration is not relevant to this respondent, but maybe more correct given the nature of the answer, that the lack of relevance is due to some gaps where a Need Analysis could help to improve the existing administration.

One respondent explains why not all options are selected due to “a strong technical background” indicating that the opt-out is not because of the non-existence of the options in the institution, but because they are not relevant to the respondent. The respondent furthermore advocates that – in part sparked by the pandemic – a strong and fully elaborated organizational framework for educational technology support is very important to avoid teachers less technically strong will “slide back into doing things the old way”:

“I am not personally using all of the elements indicated in the previous question, as I have a strong technical background. However, the vast majority of teaching faculty here do not have strong backgrounds leveraging technology to create seamless learning experiences. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been heavy reliance upon technical support teams, as well as on knowledgeable peers and dedicated teaching and learning support staff to provide training and guidance. I think that it is essential that you have administrative buy-in and explicit support for such initiatives, otherwise many faculty will simply let the efforts slide, and will slide back into old ways of doing things. It is also essential that both students and staff are provided with resources and guidelines that will help them “find their way” and successfully navigate using technology as part of the teaching and learning experience.”

Furthermore, one respondent answers that the campus for the staff provides the aforementioned options.

The fact that some universities are now adding a virtual dimension to their presence in society in the aftermath of the pandemic is both due to new insights, but also for competitive reasons. I will address this in the suggestions and conclusions section.

The following closed-ended technology specific question aims at determining how “the landscape” of technology infra-structures looks like in the respondents’ institutions as it has a great importance to the possibilities of scaling technology supported education, teaching, and learning, and of course is also important to how the framework for support is or can be organized.

Where suggested options are not selected, either it could indicate an actual lack of the technology or that the respondent is not aware, whether the technology is present on campus (Figure 7.5).

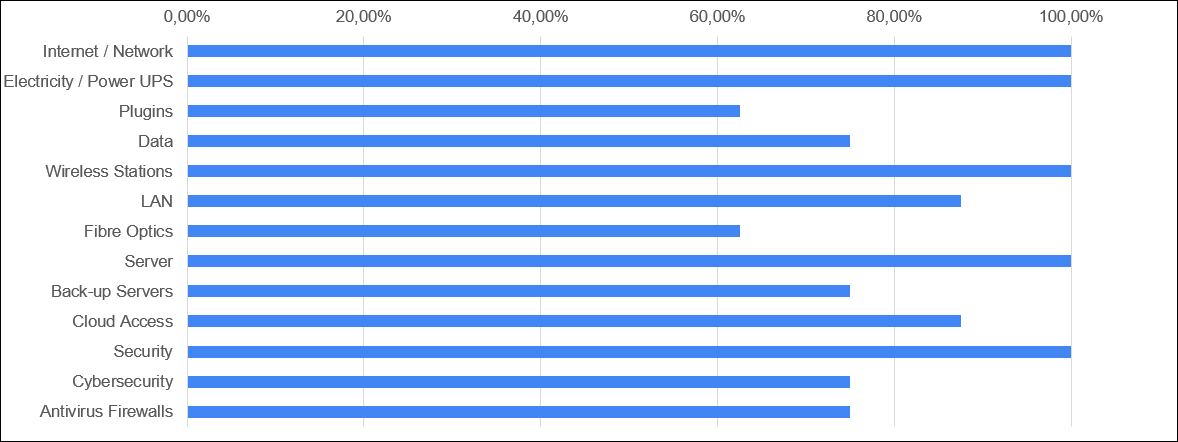

Technology specific questions: 2. What technological infra-structure is available to your students and lecturers on the campus. (8 responses).

Figure 7.5

The technological infrastructure available to students and lecturers on campus for the total of the countries

The answers are interesting as they indicate that some technologies are not present on campus; technologies that are quite important either to security or usability.

For instance, only 62.5% indicate that plugins are part of the technological infrastructure on campus (Figure 7.5). This can be due to a conscious choice from the IT-department – for instance if there are no Language labs present, there will be no need for plugins supporting different alphabets, audio software or the like. It can also be that there is no support for plugins on BYOD.

All institutions have servers available to students and lecturers, however only 75% of them offer back-up servers (Figure 7.5).

When it comes to cybersecurity 75% offer this service to students and lecturers and the same number applies for Antivirus firewalls (Figure 7.5). One respondent has added a comment to the options in question 2:

“It differs between students and lecturers. The students do not have access to everything the lecturers have.”

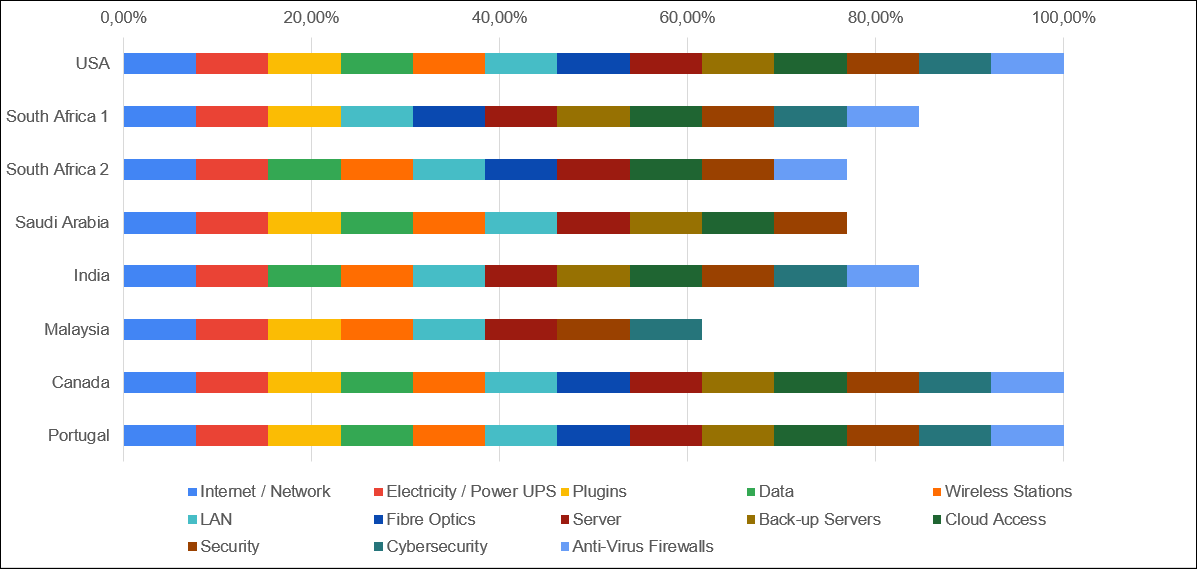

Figure 7.6

The technological infra-structure available to students and lecturers on campus per country

The original answers from the respondents from University of the Free State in Figure 7.6 were interesting as they were different from each other. One respondent indicated that LANs are not available, the other that LANs are available. This could either be due to that the respondent is not familiar with the technical term, it could also be that the respondents are working in different departments with different policies or available technology. It could also be because of security issues, which is supported by the fact that Cybersecurity is neither available to the respondent reporting LANs were not available. However, a follow-up on this issue revealed that in South Africa 1 there are stations with LAN connection to students and lecturers, so Figure 7.5 and 7.6 was updated with the new information. The overall finding here is that there is an economic divide between richer countries and poorer countries, which is reflected in available technology.

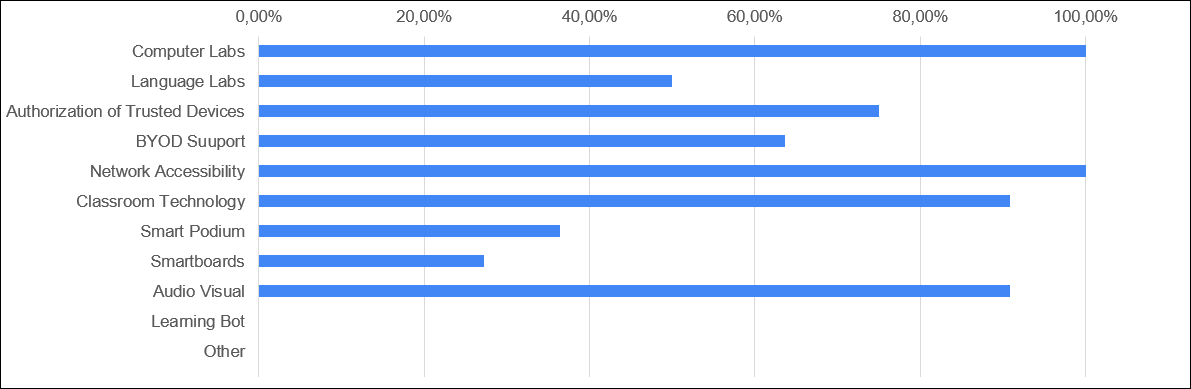

Technology specific questions: 3a. What technological facilities are available to your students and lecturers on the campus. (8 responses).

Figure 7.7

Technological facilities available to students and lecturer on the campus for the total of the countries

The answers in Figure 7.7. show most common facilities are supported on campus (Computer labs, Network accessibility, Classroom technology, Audio Visual, and Authorization of trusted devices) whereas Language labs (50%), Smart Podium (37.5%) and Smartboards (25%) are not that widespread. Smart Podium and Smart Boards are an addition to other relevant classroom technology like Projectors, which is not specifically mentioned as options in the survey but could be part of the “Audio Visual ” or the option “Other”. However, one respondent specifically mentions the projectors as part of classroom technology.

In none of the campuses learning bots or other technologies seem to be available to students and lecturers.

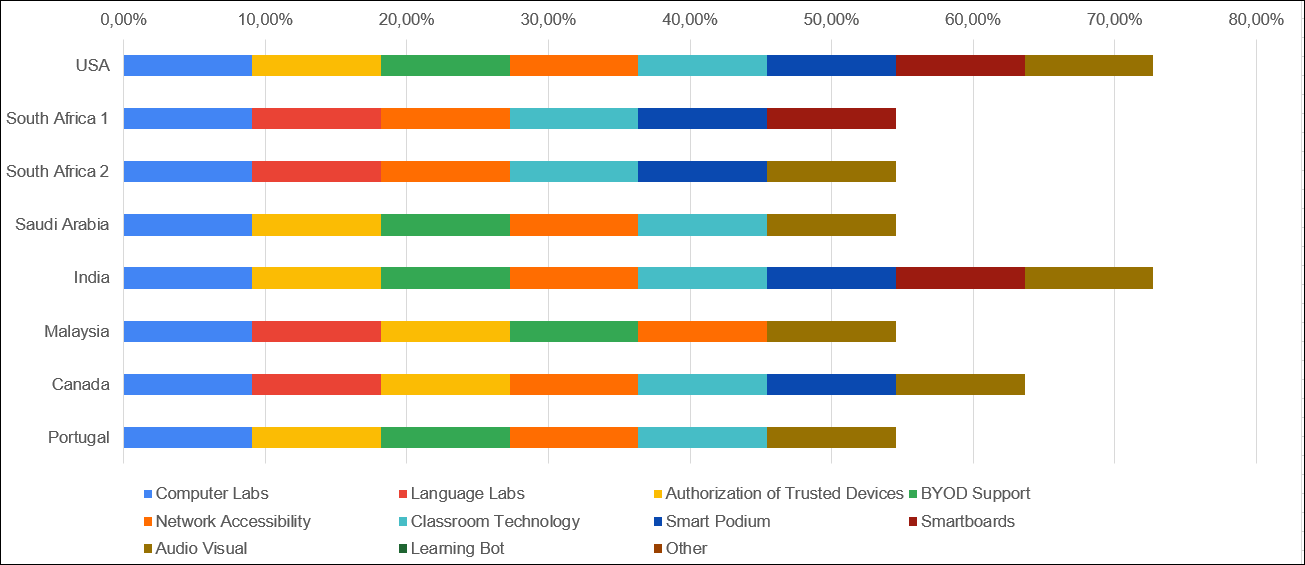

Figure 7.8

Technological facilities available to students and lecturers on the campus per country

In the more granulated Figure 7.8 we see that Authorization of trusted Devices and BYOD support (Bring Your Own Device) are not available to both respondents at University of the Free State, but while Smartboards are available to one of them this resource is not available to the other, maybe indicating they work in different departments? There also seems to be a lack of Language labs. An explanation could be that language labs have been replaced by other technologies. Online resources for example. However, language labs can be relevant in multi-language countries where some kind of English or other language ability is necessary to participate in a specific course and/or to support students’ retention rates.

Technology-specific question 3b: Elaborate in your own words what and how you are using the selected options in Question 3a.

From the answers we can see that the facilities offered, and the use varies from campus to campus with examples mentioned (but probably not limited to) below:

- Some of the technological facilities are only provided by campus for lecturers

- That multi-platform technologies are available/supported (Apple Mac, PCs, and Dell laptops). A mobile cart is offered to students without or limited access to relevant technology. 1:1 in terms of smartphones, but not all students have laptops. There is technology in Hy-flex classes.

- In at least one university the facilities are managed centrally (computer labs).

- Students have both on-campus and off-campus access to library resources, information services, exam results and research resources (not further specified).

- That some of the technologies might be available, but only the ones the respondent is being exposed to are mentioned and there might be more/other technologies the respondent is not aware of.

- The technologies are also used to support the creation and delivery of the online courses.

To obtain more information, interviews or a general questionnaire follow-up could be applied in a next round of research.

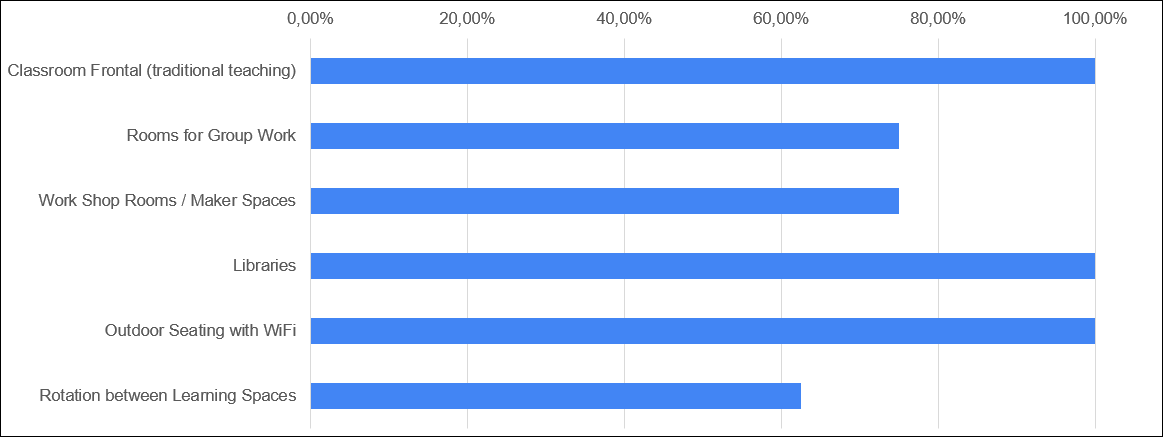

Technology-specific questions: 4a. Learning Spaces – Please elaborate on each of these elements in your own environment. (8 responses)

Figure 7.9

The appliance or existence of learning spaces for the total of the countries

Most of the mentioned learning spaces are either available or utilized in the respondents’ own environment (Figure 7.9). However, there are some differences, which can stem from differences in education offered on campus. For instance, Workshop rooms/Maker spaces (75%) are usually more relevant/necessary when offering education, which requires manual skills/training of some kind. It could be music or gym in the teachers’ education, labs/tools in the engineering education, labs for the bioanalysts’ education, the nursing education, etc.

Not all environments seem to use rooms for Group Work (75%), and rotation between learning spaces (62.5%) are also limited, while Outdoor seating with WiFi (100%). However, one respondent specifically mentions “two large rooms” used for both group work and workshops.

The lesser extent of these learning spaces can either be due to the education offered as mentioned above, but also stem from insufficient funding. One answer that sticks out is one where Classroom Frontal traditional teaching is not applied. Unfortunately, this option is not elaborated upon by the respondent in the following open-ended question 4b. It could be that it is in a specific educational setting.

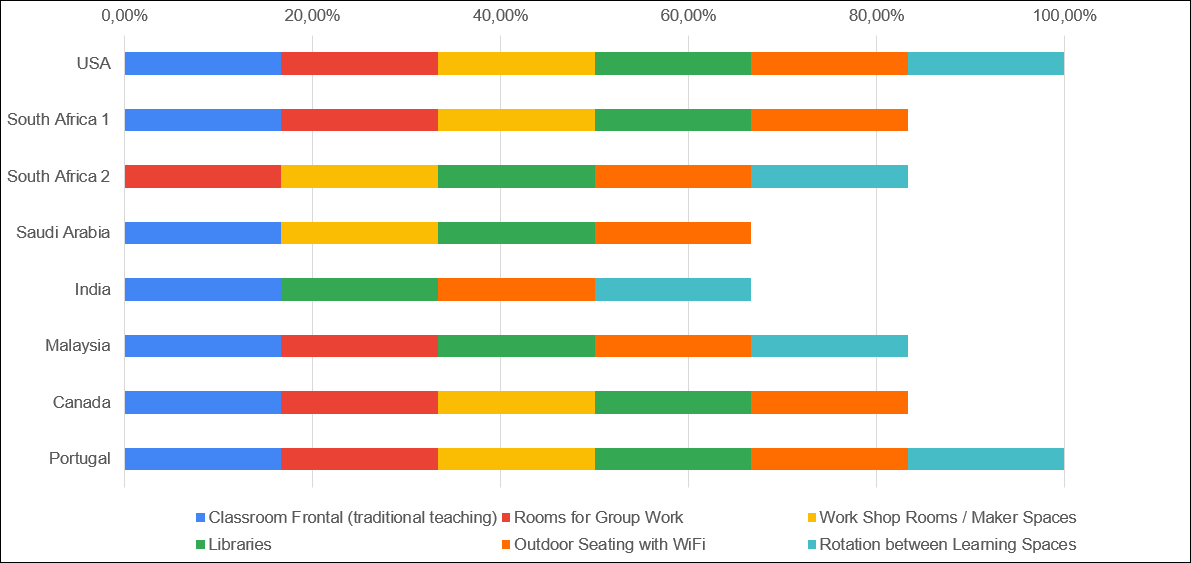

Figure 7.10

The appliance or existence of learning spaces per country

Figure 7.10 shows that two institutions cover/offer all the listed learning spaces, while the remaining is more spread. Lower percentages on rooms for Group Work and Workshop rooms/Maker Spaces. This finding could both be because of under-funding, differences in education offered or other reasons, and should be part of an in-depth approach.

Technology specific questions: 4b. Elaborate in your own words what and how you are using the selected options in Question 4a.

This open-ended question provides some additional information to the options chosen in question 4a.

- All areas are available for students

- Ours [environment] is an interdisciplinary higher education system, and thus the pedagogy involves different modalities, some includes lab work, visit to outdoor locations, guest lectures etc.

- Most classes do take place in the traditional lecturing style, but students are allowed to work outside in groups – with WiFi if needed. Libraries are available on all campuses.

- Practice during the classroom teaching in campus

- The students and the Professors have access to several spaces with learning facilities.

We will discuss this further after the presentation of the outcome of the Teaching Culture, and Theories and Methodologies questions.

7.3.5 Teaching Culture, and Theories and Methodologies

The questions covering the teaching culture consist of three (3) closed-ended questions:

- Question 1: What is the learning culture at your institution in terms of student-lecturer relationships?

- Question 1a: Which pedagogical and methodological approaches are you following?

- Question 1b: Which levels of learning are included in your classroom’s (Bloom’s taxonomy)?

Following the three closed-ended questions is an open-ended question providing the respondents the opportunity to elaborate on the previous chosen options. We used these specific topics because we wanted to look at management of learning spaces and learning culture.

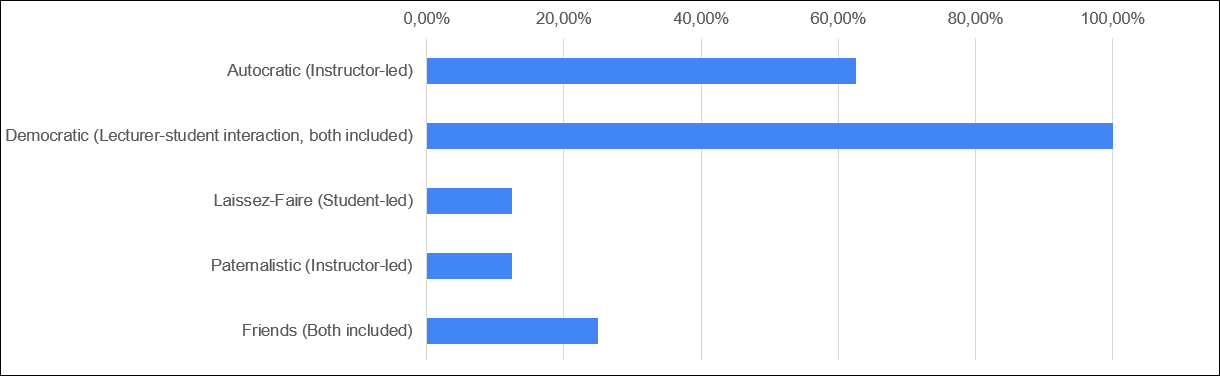

Teaching Culture: 1. What is the learning culture at your institution in terms of student-lecturer relationships? (8 responses).

Figure 7.11

Percentage of learning culture applied in terms of student-lecturer relationships for the total of countries

The dominant learning culture (Figure 7.11) turns out to be Democratic (100%), followed by Autocratic (62.5%). It is not too surprising in a traditional setting of teaching culture in the countries the respondents come from. However, it is interesting considering the use of technology during the pandemic; does the pandemic support already existing patterns of teaching culture leaving out the more self-organized or “free” teaching alternatives? Is it that lockdowns rule out a physical presence thus only leaving the traditional teaching culture characterized by very structured teaching? Another possibility is that some of the questions have been misinterpreted.

The reason could also be that most institutions already have worked with an elaborate and conscious teaching strategy within technology-supported teaching and learning and the pandemic has not yet lasted long enough to have a significant impact on the culture so far. These are certainly questions that should be part of future research.

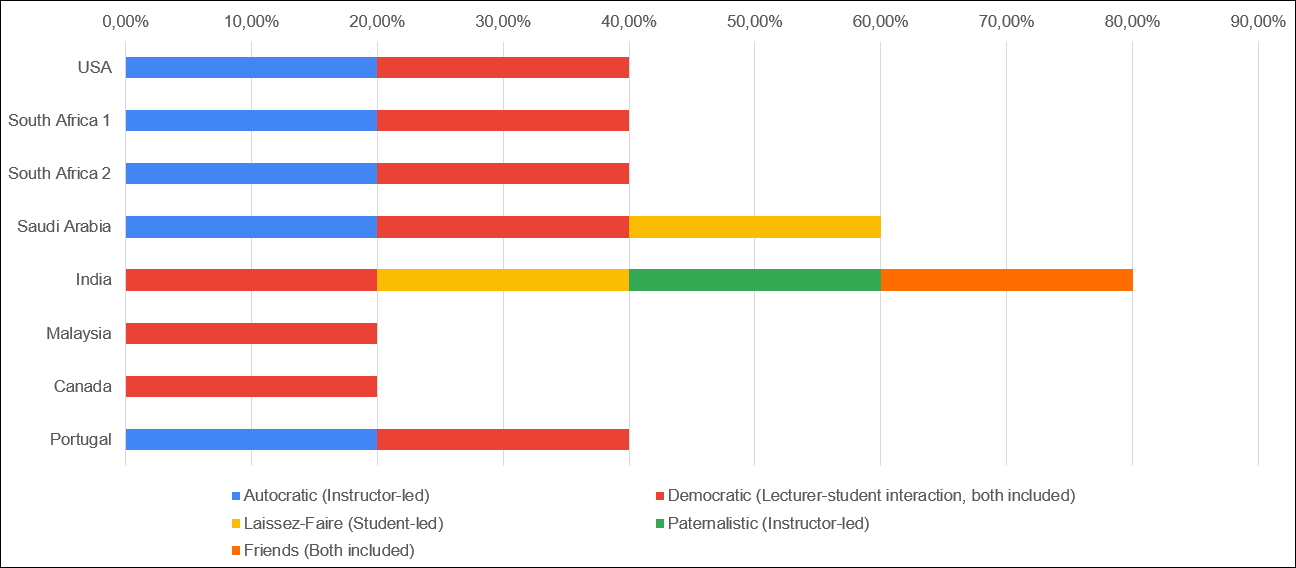

Figure 7.12

Distribution of learning culture applied in terms of students-lecturer relationships per country

Figure 7.12 reveals that except one HEI the existence of Laissez-faire and Paternalistic learning culture is non-existing – at least to the knowledge of the respondents. There seems to be a very uniform learning culture at most institutions. Five of the institutions are dominated by the Autocratic and Democratic learning culture in terms of the student-lecturer relationship, two institutions only have the democratic learning culture, while one country (India) sticks out having four learning cultures in terms of the student-lecturer relationship only leaving out the Autocratic learning culture. A follow up question would be how the four learning approaches have been applied. Again, the differences in learning approaches could also be due to the subject taught.

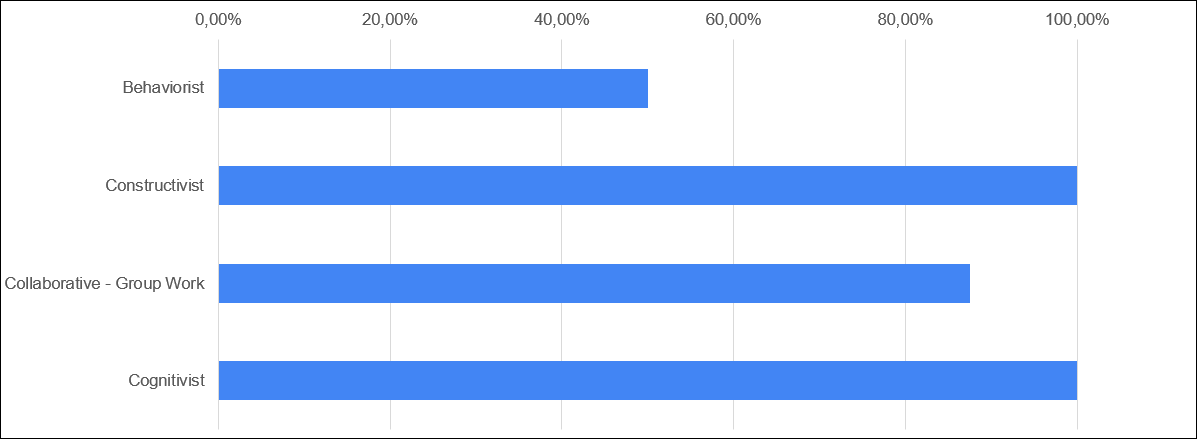

Theories and Methodologies: 1a. Which pedagogical and methodological approaches are you following? (8 responses).

Figure 7.13

Percentage of pedagogical and methodological approaches for the total of the countries

The percentages (Figure 7.13) might give some answers: the Constructivist and Cognitivist pedagogy and methodology dominate the approach followed (100%), and Collaborative – group work is ranging high (87,5%). The Behaviorist approach is less represented (50%).

This is in part a bit puzzling: collaborative – group work should be more difficult to carry out in a pandemic where lock-down and physical presence is limited compared to in a pre-pandemic setting. However, the percentage is high. One should also think that in an undergoing pandemic the behaviorist approach could be an advantage as measuring learning would be a “fallback” method to assessing progress in a non-physical learning setting and providing motivational feed-back.

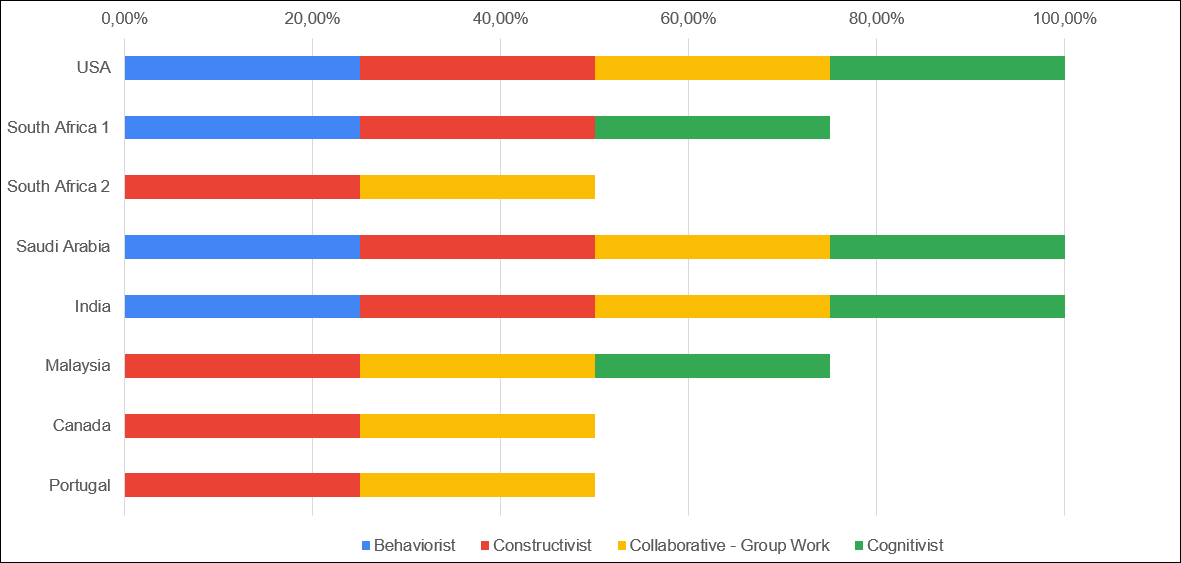

Figure 7.14

Distribution of pedagogical and methodological approaches per country

In Figure 7.14 we see that different pedagogical and methodological approaches are being used in the same institution (University of the Free State). It is possible that it is related with the subject taught as the learning culture in terms of student-lecturer relationships is the same (Figure 7.12), which also have been confirmed in a later conversation with the respondent explaining that the subject is a preparatory course on second year, which is being followed by a much more practical hands-on course.

Is the behaviorist and cognitivist approach missing in some HEIs because traditional teaching has not been affected by the pandemic due to good organizational support of the technology supported education? One answer might lie in the comment made by one of the respondents earlier (Technology Specific Questions: 1b.):

“I am not personally using all of the elements indicated in the previous question, as I have a strong technical background. However, the vast majority of teaching faculty here do not have strong backgrounds leveraging technology to create seamless learning experiences. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been heavy reliance upon technical support teams, as well as on knowledgeable peers and dedicated teaching and learning support staff to provide training and guidance. I think that it is essential that you have administrative buy-in and explicit support for such initiatives, otherwise many faculty will simply let the efforts slide, and will slide back into old ways of doing things. It is also essential that both students and staff are provided with resources and guidelines that will help them “find their way” and successfully navigate using technology as part of the teaching and learning experience.”

Another answer to the high percentage of Collaborative – Group work and the Constructivist approach might be found in the pandemic boosting the necessary use of technologies supporting synchronous communication and collaborative work, this phenomenon could be continued during or after the pandemic. For instance, the video meeting tool Zoom saw an increase of 3.3% from January 2020 to October 2020 (Dean, 2022).

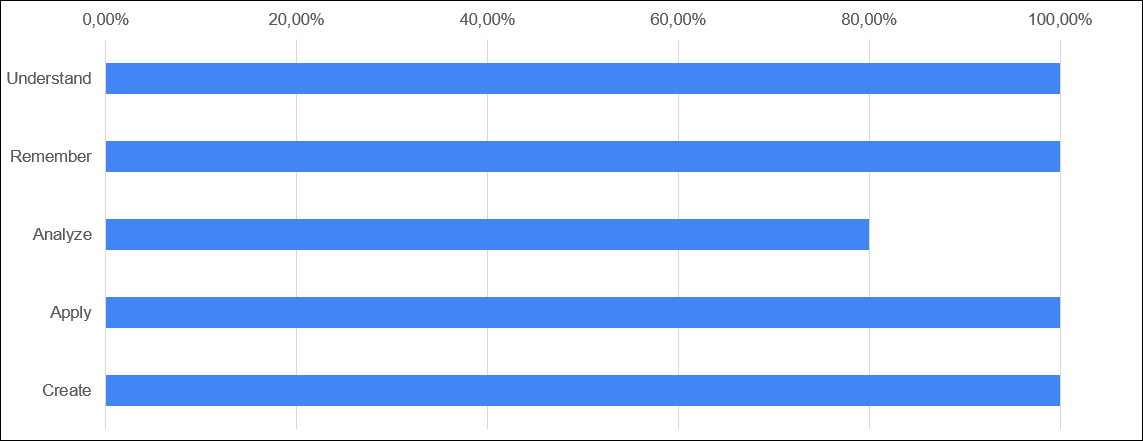

Theories and Methodologies 1b. Which levels of learning are included in your classroom’s (Bloom’s taxonomy). (8 responses).

Figure 7.15

Levels of learning included in the classrooms

The answers show that most levels of learning are applied in the teaching situation. The only one that sticks out is “Analyze”, but the respondent explains in the comments that this level is not meaningfully applicable in the specific course taught. However, in PBL Analysis is important. The students do not analyze, but they apply. This is an indication that the understanding of Blooms’ taxonomy needs more attention.

Theories and methodologies 1c. Elaborate in your own words what and how you are using the selected options in question 1a and 1b. (6 responses).

This open-ended question is the last of the Technology part of the survey. The answers below:

“We incorporate the selected learning theories into the designs. Undergraduate classes emphasize behaviorist and lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Graduate designs are more focused on the higher levels and expect students to own and manage their learning more.”

“Understanding and remembering are basic levels for any kind of information assimilation, with that our teaching and learning practices include relevant experiences where students take control of their learning through interactions with the community at large too.”

“My subject covers social entrepreneurship as a “new” approach to the viability of civil society organizations. Over and above the traditional theory, legal formats and business approaches are taught and students need to be able to apply some of the practical knowledge – and “create” in theory at least, their own social entrepreneurial business plans.”

“Practice the teaching approaches when in the classroom. For 1(b) practice when teaching and create an assessment.”

“I teach research methods and the students need to understand the concepts of knowledge, research questions, methods, data collection and analysis and others. They also need to remember them, as they need to do several presentations. Moreover, they need to apply the knowledge acquired in creating data collection instruments, to analyze the data collected, and in the case of a research project, they need to implement it, and to create solutions based on the knowledge developed during the course.”

The answers reveal a great deal of conscious use when designing the courses. One respondent even uses the theories and methodologies when teaching, which also probably would lead to reflection regarding one’s own teaching practice. This would be the ultimate aim of a continuous improvement in ones’ teaching practice.

7.4 Discussion

How can seamless learning be implemented based on availability of technology and understanding of pedagogical approaches or methodologies?

From the findings seamless learning is not quite seamless when it comes to the technological support be it infrastructure, facilities, or support. The users have faced various problem-solving issues during the pandemic. The student access to the internet when not being able to study on campus have led to different supportive actions. Also lecturers have faced a transformation from on premise to online teaching. An interesting perspective that has not been a direct part of this research is how the administrative and supporting staff have experienced the transformation to online education. What practical issues did they have to deal with? How did they come about them? And have these – for many parts – ad hoc interventions resulted in permanent organizational changes and policies?

The seeming gap between the organizational knowledge of the users’ needs and the users’ knowledge of available technology or support is an obstacle til seamless learning when technological barriers appear.

Some questions:

- What learning took place during the pandemic? Where / How did the role of technology change (from support to necessity).

- Impact of learning without access to technology? The gap between the first and third world.

- What can a Post-pandemic learning environment look like?

- Are there technological ways of bridging possible gaps between the end user and the centralized IT-department?

It is quite clear that the transition from on premise to online teaching has brought all kinds of practical challenges that needed to be solved in order to create some kind of space for teaching and learning. These efforts have succeeded to some degree and have probably led to some both individual and organizational learning regarding practicing online teaching. What is important now is to collect these learnings and bring them into play in a new mode of learning spaces and environments.

From the findings, the differences between the HEIs participating in this survey have shown that it is possible to transform education from on premise to online driven by bitter necessity. However, the access to technology varied from country to country, and from institution to institution.

The numbers in the tables clearly indicate that HEIs in the richer parts of the world have access to a more broadly founded technological infrastructure than HEIs in the more poor parts of the world meaning that some HEIs have a shorter technological path to supporting seamless learning.

- The different conditions for the HEIs around the world when it comes to funding obviously plays a significant role. Can the pandemic lead to changes in funding for the HEIs?

The extent to which the organizations, lecturers, and students have been interacting in this testbed of transformation, indicate that the different ways each country is funding their HE, have probably impacted on the possibilities of carrying out teaching, supporting the teaching efforts and ultimately also the learning outcomes and the student retention rates. Also, different national funding policies seem to affect the financial sustainability of the HE systems and HEIs in the different countries from the same impact of COVID-19 (Crawford et al., 2020).

Some HEIs in this research have been funding students’ Mobile WiFi access in order to establish a possibility for them to attend the classes online. Others have extended their outside WiFi capabilities, so students could go outside of the campus to get network access and participate in online classes.

From digital twins of existing on-premises courses over the implementation of HyFlex courses and to temporary or permanent changing student/teacher support and accessibility the efforts have been multiple, and both in HE and in the general work market there is a “before” and an “after” the pandemic but with a divide between the richer countries and the poorer countries. In rich countries virtual meetings have been taking over physical meetings, not all kinds of meetings, but some. Some companies have cut down on their physical office spaces allowing their employees to work from home several days a week, or maybe even 100% online.

In Malaysia language tests have been run previous to the pandemic, but this was changed to online tests during COVID-19 and might have replaced the existing language labs. In the USA digital twins of existing on-premises courses have been developed as well as HyFlex courses. In Canada multi-modal courses have been developed

Within HE some courses are more likely to go virtual than others that require physical training, so we will probably experience a higher degree of technology implemented or embedded in courses taught.

Some indications of different funding policies are emerging. The strategies in online HE the Nordic countries are for example not similar despite the close cultural ties and similarities regarding the Nordic HE systems focus on tuition-free higher education and government funding of teaching and research. Whereas the government in Norway has worked on defining the approach to digital education through a state-led approach, the situation is different in Denmark and Sweden with a more bottom-up approach, leaving each single institution to find its own way. Regarding the impact from the pandemic onto the economic basis for HEIs in the Nordic region the public funding af HE seems to have had a stabilizing factor compared with the budget cuts that have been announced in countries like the USA and the UK (Laterza et al., 2020).

There could be some technological solutions to bridging the knowledge gap between the organization (HEI) and the users (students, faculty, and staff) through utilizing Learning Analytics and BI in a combination to establish a more 3-dimensional model of the educational landscape a HEI consists of, and a transparency that would also benefit to all the involved actors in this landscape.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Technology did not solve all the practical challenges with the necessary transition from on premise to online teaching and learning. However, there can be no doubt that a global situation where countless students, lecturers and HEI have been forced to work online, have brought very valuable knowledge to the world of HE. The crucial point is to which extent it will be formalized and supported in the future post-pandemic era. Will the actors in HE slide back into the former patterns of conduct or will these learnings be implemented as new ways of supporting learning and teaching?

One of the respondents put it this way:

There has been heavy reliance upon technical support teams, as well as on knowledgeable peers and dedicated teaching and learning support staff to provide training and guidance. I think that it is essential that you have administrative buy-in and explicit support for such initiatives, otherwise many faculty will simply let the efforts slide, and will slide back into old ways of doing things.

Some of the answers from the survey have revealed that some respondents have been “lone riders” and have had to deal with some involvement in practical issues which really is an organizational responsibility. Overall, there seems to be a great deal of organizational support for the lecturers, and the experience from the time during the pandemic will probably contribute to strengthening this support by identifying weak spots.

There also seems to be a gap between what the HEI organization knows about the users’ needs, and the users’ knowledge of the available technologies, facilities, and support in the organization. This gap leads to a lack of consistent strategy regarding the sufficient technology supporting the teaching and learning in the HEI further leading to inefficient budget spendings and uncoordinated efforts from various departments, sometimes leaving the users to invent their own infrastructure or the organization to make ad hoc decisions.

The various systems and business models of funding HEI have shown financially vulnerable to a pandemic, which have led to budget cuts, either directly or due to economic impacts on the funding parts. This shows the vulnerability of HEI in times of extremes like a pandemic is, where tradition and usual patterns of physical movement suddenly becomes a hazard. This vulnerability should be addressed. Even though technology played an important role in HEI – and in the work markets as well, the pandemic also made the divide between rich countries and poorer countries very clear.

When a large proportion of the world’s workforce is made up of day laborers, surviving the pandemic becomes of a higher importance than paying for an education.

Numbers from the UN show that COVID-19 has wiped out 20 years of education gains, and an additional 101 million or 9% of children in grades 1 through 8 fell below minimum reading proficiency levels in 2020 (United Nations, 2022). When these younger generations grow up they may miss an opportunity to take part of the HE in the countries most heavily affected by the pandemic. This might affect or lead to shortages of various professions like nurses and other essential workers. Access to technology is very unevenly distributed, and the different funding systems also impact the HEIs in their ability to provide the same amount of candidates to society. This is also discussed in Chapter 4 in this book.

Recommendations for the Post-Pandemic Era

- Incorporate the learnings from dealing with technology infrastructures and support geared to a pre-pandemic era into an organizational framework.

- Identify employees (both faculty and staff) who can contribute to strengthening the organizational framework supporting teaching and learning in a setting of formalized and focused effort i.e. make a strategy and carry it out with sufficient resources.

- Bridge the gap between the organizational knowledge of the users’ needs and the users’ knowledge of available technology, facilities, or support – for instance through mapping and analyzing the available technology and facilities, user learning patterns (Learning Analytics) and learning spaces in the individual HEI by using BI-reports that can work as a dialogue tool to find these gaps.

- Discuss sustainable business models of the funding for HE – engaging in UNs 4th goal: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. Many universities support the 17 goals, and there might already be alliances focusing on this.

References

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Magni, P., & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), pp.1–20. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Dean, B. (2022, January 6). Zoom User Stats: How Many People Use Zoom in 2022? Backlinko. https://backlinko.com/zoom-users#zoom-stats

Eyisy, D. (2016). The Usefulness of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Researching Problem-Solving Ability in Science Education Curriculum. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(15), pp. 91-100.

Gibbons, L. (2017). Exploring Social Complexity: Continuum Theory and a Research Design Model for Archival Research. In A. Gilliland, S. McKemmish & A. Lau (Eds.), Research in the archival multiverse (pp. 762-788). Monash University Publishing.

Google (n.d., a). Google Drive: Easy and secure access to all of your content. https://www.google.com/intl/en_ca/drive/

Google (n.d., b). Google Forms: Get insights quickly, with Google Forms. https://www.google.ca/forms/about/

Laterza, V., Tømte, C. E., Pinheiro, R. M. (2020). Digital transformations with “Nordic characteristics”? Latest trends in the digitalisation of teaching and learning in Nordic higher education. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 15(4), pp. 225–233.

Microsoft (2022). Word. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/word

Moodle (n.d.). https://moodle.org

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books. https://dl.acm.org/doi/book/10.5555/1095592

Piaget, J. (1957). Construction of reality in the child. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Sutrisna M, (2009, May 12). Research Methodology in Doctoral Research: Understanding the Meaning of Conducting Qualitative Research. ARCOM Doctoral Workshop [Workshop], 2009, Liverpool John Moores University, Merseyside, United Kingdom.

United Nations (2022). Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.