A Curriculum-Wide Defense against Zoom Fatigue

Andrew Coop; Lisa Lebovitz; Shannon Tucker; and Cherokee Layson-Wolf

Andrew Coop, Professor and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore | acoop@rx.umaryland.edu

Lisa Lebovitz, Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore | llebovitz@rx.umaryland.edu

Shannon Tucker, Assistant Dean for Instructional Design and Technology, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore | stucker@rx.umaryland.edu

Cherokee Layson-Wolf, Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Student Affairs, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore | cwolf@rx.umaryland.edu

What?

A team that has responsibility for academic affairs, student affairs, assessment, and technology delivery at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy came together during the COVID-19 pandemic to blend the best practices of student-centered online learning environments with the competency-based needs of our Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum. Specifically, our major focus was minimizing “zoom-fatigue” and ensuring wellness at a curriculum level, rather than course or class level.

The PharmD degree is a professional doctorate, with three years of mostly didactic courses and skills labs followed by a year of advanced experiential rotations. The didactic portion was traditionally offered as a full-time, in-person program, with course activities and assessments spanning 8:30 am-5:00 pm, Monday-Friday. During the initial emergency pivot to virtual delivery in Spring 2020, we transitioned academic and assessment activities to synchronous and online following our existing schedule. Student, faculty, and staff feedback showed negative effects on well-being, and our Fall 2020-Spring 2021 solution was a student-centered, coordinated approach to scheduling that limited synchronous time across the entire curriculum.

We worked with course managers to create a blended delivery model that balanced the use of asynchronous and synchronous delivery methods in a predictable schedule that supported students across different time zones, as many students chose to move home to shelter in place. It also created a model where synchronous activities were at consistent times, providing a structure for the students.

So What?

Virtual delivery of didactic education is the future, but “Zoom fatigue” severely limits student learning (Sharp, Norman, Spagnoletti, & Miller, 2021, p. 13). Zoom fatigue has been defined as “exhaustion with overuse of virtual platforms” (Wiederhold, p. 437). Being in a web conference uses a great deal of cognitive energy because it violates so many social norms and because academic classes are scheduled all day (Amenabar, 2020; Rutledge, 2020; Sharp, Norman, Spagnoletti, & Miller, 2021; Supiano, 2020). Over the summer it became clear we would not return to in-person in the fall, so we reviewed a range of suggestions for limiting Zoom fatigue, which focused on the delivery of individual sessions (breaking into modules with breaks), or from the point of view of the recipient, such as allowing time away from the screen (Sharp, Norman, Spagnoletti, & Miller, 2021; Rutledge, 2020; Supiano, 2020). Our observations of the emergency pivot showed us that it was far less than ideal to have back-to-back classes, even if faculty did end their classes at 10 minutes to the hour, which did not always happen. The sheer number of classes in a day led to students reporting they could not stay engaged after about 2-3 hours.

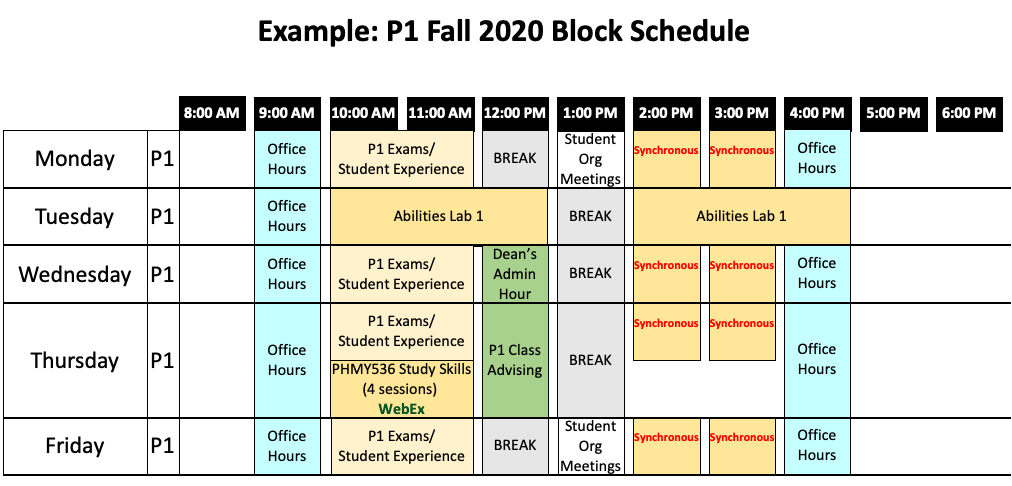

As such, we proposed to the faculty a complete restructure of the academic schedule at a curriculum level, starting from a maximum of 2-3 hour blocks of synchronous activities, together with designated breaks. Due to students being widely located, we also limited the work-day to between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm EST, to allow for different time zones within the US. Exams were offered virtually, and all took place at the same time of 10:00 am EST. We specifically scheduled office hours to aid faculty and students with their structure and time management. An example of a “block schedule” is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example: P1 Fall 2020 Block Schedule.

After the development of the “block schedule” came the difficult step of gaining faculty buy-in for redesigning all academic courses to be consistent with the block schedule, in time for Fall 2020 implementation. The three academic departments within the school each have a Vice Chair of Academic Affairs (VCs). Together with the authors, the VCs developed a philosophy for delivery and assessments and guidance documents based on the core value of “minimizing Zoom-fatigue and ensuring wellness at a curriculum level.” It was key that faculty have the opportunity to review and provide feedback on the guidance documents, which were then also approved by the faculty governance body.

After approval in the early summer, we assigned Instructional Design and Academic Affairs staff to each course to aid the faculty leader of the course, the course manager (CM), to help guide the transition from in-person to distance learning. We conducted frequent CM meetings by class year to ensure progress, collaboratively solve problems, and optimize the plan based on collective experience throughout the summer. We scheduled one CM meeting to decide collectively how to balance instructional preferences for synchronous learning and the best-practice rationale for limiting total synchronous time to help students optimize their learning. This resulted in negotiating the number of course contact hours delivered synchronously down to less than 50% of pre-COVID-19 course contact hours. The remaining contact time was shifted to asynchronous delivery including pre-recorded lectures and out of class assignments. To support this change, we worked with faculty to develop new approaches for asynchronous delivery, and new assessment techniques beyond our traditional exam format. We also arranged numerous town halls with both students and faculty to describe the approach and philosophy, and took all feedback into the planning process.

Now What?

Achieving the Goal

Our approach described above involved significant effort in terms of communication with all parties, and to no surprise there were a range of contrasting opinions among all stakeholders. The need for clear leadership while embracing faculty governance is often a difficult path. We therefore encourage all who follow a similar approach to ensure the involvement of all stakeholders, and clear communication about the process for decisions, and being active participants in the process.

Measuring Student Workload

We found that the incorporation of asynchronous activities (such as readings, video watching, or assignments) led to perceptions of increased workload and effort by students; the common phrase being “You’ve just added more stuff!”. As such, whether real or perceived, this was an important aspect for us to address. We reinforced the use of Carnegie Units as a measure of total student effort to align with the traditional 15 hours of lectures equaling one credit. We adopted the Enhanced Course Workload Estimator from the Wake Forest University Center for the Advancement of Teaching (n.d.); we asked all faculty to utilize it in their planning and to include this calculation on course syllabi for transparency. Importantly, we communicated to students that this estimator was being utilized to plan their overall course workload, to help inform their perceptions about effort.

Assessment

A survey was generated to ask both faculty and students of their perception of quantity, length, and placement of synchronous sessions, with the majority agreeing the length (2-3 hours daily), the number of sessions, and the placement (between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm) were all appropriate.

Instructional Designers

Our assignment of instructional designers was critical, as they provided guidance to the faculty and ensured timelines were met. One added benefit we found was holding frequent meetings of the instructional designers themselves as a group to share experiences, and ask questions from each other.

A Guide Is Needed

The regular, limited synchronous sessions allowed a regular schedule so both students and faculty could plan around those sessions. We received feedback that the flexibility of the asynchronous activities was welcomed by many students, but also heard from a significant number that a lack of structure for the asynchronous activities was a new experience. To address this, as we moved to the spring, we incorporated additional guides for the students in terms of proposed times to complete asynchronous activities. This was an important finding, as many students have only experienced traditionally structured educational models, and require mentorship in developing skills to manage asynchronous activities.

Future

As the fall 2021 semester began, we transitioned to return to campus but retained the model of a blend of limited synchronous activities, now in person, supplemented by asynchronous activities. We retained the approach to allow students the flexibility they seek through optimizing physical presence on campus to allow for increased engagement with faculty, staff and importantly, each other. It also allowed them to plan academics around other commitments. This flexibility is critical for future students who are diverse in their backgrounds and personal situations.

Conclusion

This past year was an exercise that none of us ever envisioned having to complete. It did provide us insights with the workload necessary to make it happen, and further understand the needs of all stakeholders (faculty, administrators, staff and students) to ensure a continued effective learning process. This experience helps us to prepare logistics when future pivots are needed again, and demonstrates the success of taking a different approach and perspective to effectively deliver classroom material to our students.

References

Amenabar, T. (2020, Sept. 6). How college students can make the most of remote learning. The Washington Post. Retrieved March 10, 2022 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2020/09/06/remote-learning-college-zoom

Rutledge, P. B. (2020, Nov. 19). Suffering from Zoom fatigue? Here’s why. Psychology Today, Accessed January 28, 2021 from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/positively-media/202011/suffering-zoom-fatigue-here-s-why-0

Sharp, E. A., Norman, M. K., Spagnoletti, C. L., & Miller, B. G. (2021). Optimizing synchronous online teaching sessions: A guide to the “new normal” in medical education. Academic Pediatrics, 21, 11-15.

Supiano B. (2020, Oct. 15). Teaching: How to give students a break from their screens–in an online course. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved January 28, 2021 from https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2020-10-15

Wake Forest University Center for the Advancement of Teaching. (n.d.). Workload Estimator 2.0. Retrieved March 10, 2022 from https://cat.wfu.edu/resources/tools/estimator2/

Wiederhold, B. (2020). Connecting through technology during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom fatigue”. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(7), 437-438.