Finding the Silver Lining in a Pandemic: A Virtual International Interprofessional Education Course in Partnership with Older Adults Living in Baltimore, MD

Daniel Z. Mansour; Suvi Hakoinen ; Niina Mononen; Merton Lee; Diane B. Martin; Marja Airaksinen; and Nicole J. Brandt

Daniel Z. Mansour, Interprofessional Clinical Coordinator, The Peter Lamy Center on Drug Therapy and Aging, University of Maryland, Baltimore | dmansour@rx.umaryland.edu

Suvi Hakoinen, PhD candidate, Pharmacy, and Medication Safety Planner, Keusote/University of Helsinki, Finland | suvi.hakoinen@keusote.fi

Niina Mononen, Postdoctoral Researcher, Division of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Helsinki, Finland | niina.mononen@helsinki.fi

Merton Lee, Lamy Center Geriatric Pharmacotherapy Fellow, The Peter Lamy Center on Drug Therapy and Aging, University of Maryland, Baltimore | merton.lee@rx.umaryland.edu

Diane B. Martin, Director, Geriatrics and Gerontology Education and Research Program (GGEAR) and Associate Professor, Graduate School, University of Maryland, Baltimore | diane.martin@umaryland.edu

Marja Airaksinen, Professor, Head of Clinical Pharmacy Group, Division of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Helsinki, Finland | marja.airaksinen@helsinki.fi

Nicole J. Brandt, Executive Director, The Peter Lamy Center on Drug Therapy and Aging and Professor, Pharmacy Practice and Science, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, Baltimore | nbrandt@rx.umaryland.edu

Every day in the United States, 10,000 baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) celebrate their 65th birthday. By 2030, adults aged 65 and older will represent more than 20% of the American population. Moreover, by 2034, for the first time in history, there will be more people over the age of 65 than under the age of 18. This is not unique to the United States–the percentage of older adults worldwide is projected to grow from 8.5% (in 2016) to 17% by 2050 (NIH, 2016).

Healthcare systems around the world are working to identify ways to cope with the rising costs associated with the significant increase of older adults requiring complex medical care. Healthcare delivered in teams is the cornerstone of providing quality, person-centered care to older adults. It is cost effective and has been demonstrated to improve health outcomes (McCutcheon et al., 2020).

Interprofessional education (IPE) is paramount to the success of team-delivered healthcare. Throughout the country, IPE is typically delivered as a one-day activity in healthcare professional schools and programs. University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) is no different; we have a long history of delivering single intermittent interprofessional programs in which students and faculty from various disciplines come together for case-based learning. However, we now also offer a full semester IPE course, titled Interprofessional Care in Geriatrics Aging in Place. The first cohort of students representing three disciplines enrolled in the inaugural offering in 2015.

In the pre-pandemic years, the course brought together students from the seven diverse professional schools at UMB for weekly engagement with our older adult neighbors living in West Baltimore. Students are challenged to execute the goals of an age-friendly institution as they engage in a clinically focused, hands-on experience. To facilitate learning in weekly clinical huddles, students work with our neighbors in IPE teams to conduct screenings (e.g., blood pressure, fall risk, high risk medications) following the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit format.[1] Additionally, students lead the neighbors in a light exercise program, conduct home visits when necessary, and provide education and resources to assist them in navigating the psychosocial challenges affecting their ability to age in place. The overarching goal of the course is to help our older neighbors age in the community, reduce their rate of (often not needed) check-in to the local emergency departments, and decrease the rate of admissions to the hospital.

In January 2020, this program was expanded to facilitate virtual inclusion of students from University of Helsinki, Finland using Zoom technology. The pivoting to a completely virtual program due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 enabled us to fully incorporate an international interprofessional approach to care as students continued to engage with our West Baltimore neighbors via Zoom technology. As the virtual format continued into Fall 2021 and beyond, professional students from the University of Maryland, College Park also enrolled to learn and work in interprofessional partnership with the UMB and University of Helsinki, Finland students along with the participating older adults. These weekly interactions became the silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Making the Pivot

In the pre-pandemic version of the course, students facilitated health-related conversations and games and activities (such as a “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire”-style question game) each week with our neighbors. Students also conducted ad hoc health screenings and follow-ups with neighbors who would present their health concerns in sessions voluntarily. With the onset of the pandemic, this ad hoc community structure was no longer feasible. To maintain health education and outreach to our neighbors, we welcomed older adults from several communities around the Baltimore metro area who had access to the technology to join the course remotely in online “all teach, all learn” presentations. These presentations featured experts from the UMB community speaking on high-interest topics for a mixed audience and encouraged our neighbors to share experiences related to the presentation topics. That mix of students, older adults, and faculty was meant to continue to foster the communal, dialogic approach of our in-person gatherings in a new virtual setting.

To replace our individualized health screenings, we created telehealth consultations with older adult volunteers and community members in which students were able to conduct screenings based on the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit and other screening tools. These sessions occurred in virtual breakout rooms to enable student teams to maintain care and team dynamics. After these breakout sessions, students rejoined a general session in which individual groups presented patient cases and the larger team could discuss care issues and interventions.

An additional benefit to our virtual platform was the ability to increase the scope and number of collaborators in the screenings, including students from University of Helsinki (Finland). Our strategic approach to maximizing the virtual platform appears to have continued to enable students to access the rich, interactive experiences that are necessary to developing the team-based skills for adaptive, complex task coordination, as is required in interprofessional approaches to healthcare. Our efficacy in continuing to provide students with high quality learning experiences is shown in our pre/post-course survey data.

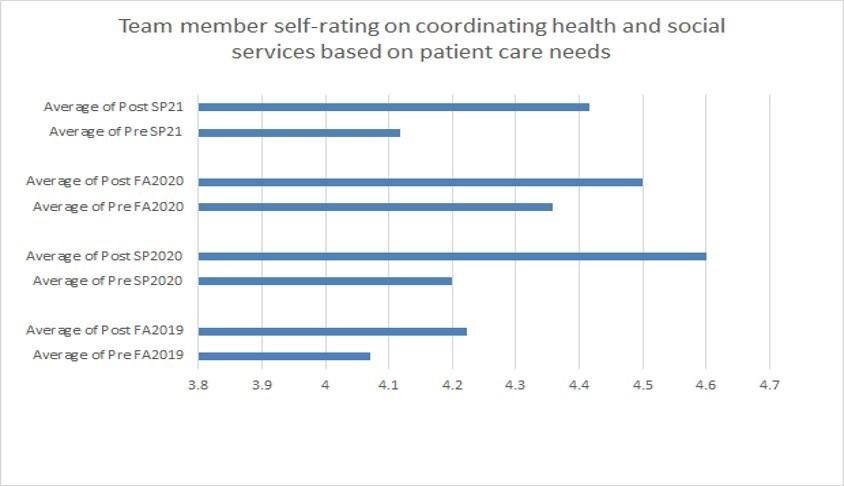

As shown in Figure 1, students enrolled in the course in Fall 2019 (the semester prior to the pandemic) rated their ability to coordinate care for older adults on average at 4.07/5 at the start of the course and 4.22/5 at the end of the semester. In Spring 2020, which began in the usual class model of interactive in-person sessions but abruptly became virtual in March 2020, students recorded a large leap in self-rated ability to collaborate to meet care needs, from 4.20/5 to 4.60/5, a difference of 0.40. The self-reported gains in skills related to collaborating to meet resident/neighbor care needs were evident in both of the next two semesters in which the course remained virtual (Fall 2020 and Spring 2021). Though our sample size is small, these results illustrate that the virtual course delivery did not negatively impact student learning.

Figure 1. Student self-rating on coordinating interprofessional services to meet patient-centered care goals, comparing pre-pandemic (Fall 2019) and concurrent-with-pandemic (Spring 2020, Fall 2020, Spring 2021) semesters.

No student was left behind in learning from, about, and with each other (IPEC, 2016). We witnessed members of the team communicate with each other in a responsive and responsible manner that supported a team approach. At the end of the experience, students were able to explain common geriatric syndromes that impacted older adults, such as falls, urinary incontinence, and frailty. As part of their course experience, students were required to complete reflective journaling exercises throughout the semester. Our internal analysis revealed that the value of this interprofessional learning experience, and comments illustrated the importance of relationship-building when working as a team member in geriatrics care. Students often shared how the course helped shape their relationship with older adults and with each other. Comments such as “It takes some time to develop the relationships” and “I truly learned a lot about myself as well as about other disciplines” were not uncommon. One social work student said, “I never knew that Pharmacists knew so much” on the heels of listening to a PharmD student present about hepatitis C in older adults.

Overcoming Obstacles

The success of our virtual format was not without its challenges.

From an international perspective: Students and faculty from Finland are used to working and studying remotely with their cameras off, resulting in a lonely, faceless learning environment that lacks a sense of community. Because everyone had cameras on in the IPE course, these participants were able to see everyone’s faces, expressions, and gestures and feel almost the same togetherness that can be felt when participating in a traditional learning environment.

From a community engagement perspective: Although many of our usual older adult neighbor participants could not participate because of a lack of equipment (computer/internet access), resulting in isolation, many others with the ability to participate experienced problems while using computers and smartphones resulting from age-related and/or disease-related changes in their mobility, dexterity, hearing, and vision.

From a teaching perspective: As course instructors, we saw an increase in the number of student participants and a decrease in the number of our West Baltimore neighbors. Lack of access to technology meant only one or sometimes two neighbors participated each week. Since we had 15 students participating in the course, interprofessional teams were often larger than what is ideal for the learning format.

From a student perspective: Working and learning as a team of interprofessional students meant that we all learned about and performed different health screenings with the neighbors. For example, it was not always the pharmacy student who checked the neighbors’ medications; it could also be the nursing student or the audiology student. This took the students outside of their comfort zones and moved them toward really learning from and about the other professionals. In addition, working with the neighbors as members of a team meant that students learned not to prejudge older adults’ concerns. They talked with the neighbors and found the root concerns underlying a particular reason for a visit, not just what the students assumed the neighbor would be concerned about.

From an interprofessional perspective: While we still experienced the usual problems with coordinating multiple faculty members with regard to scheduling, objectives, etc., we experienced new challenges while interacting with neighbors. Our course centers on their medication, safety, and social well-being; however, these were all impacted by the pandemic. For example, through our screenings we learned that some neighbors could not afford the copay of their maintenance medications; they would rather pay for food versus medication. We turned this challenge into an opportunity when students voluntarily started a food pantry initiative with five of the buildings in which our neighbors live. Furthermore, we initiated a vaccination facilitation program on the heels of many experiencing vaccine hesitancy. We also expanded a referral service for dental needs and hearing loss.

Moving Forward

While the rationale for interprofessional learning–such as greater patient complexity, the need for including patients in their care decisions, and better cost and health outcomes–becomes increasingly well-established in the literature, education and training for effective interprofessional collaboration remains a challenge. Faculty from our course have published findings that showed high-quality student learning and teamwork in geriatric care, but similar to other interprofessional courses noted in the literature, our course had been designed on complex, hands-on collaboration between faculty, students, and community members. Because our course depended on in-person interactions, converting the course to a virtual platform raised significant questions about whether high-quality learning around interprofessional and collaborative competencies would still be possible. The results of our conversion are promising though more data is needed.

Some of this data may come from our international partner, University of Helsinki, Finland. Finland is a European Union country located in Northern Europe between Sweden and Russia. It has a population of about 5.5 million people. With nearly 10% of the population over age 75, it is one of the ‘oldest’ countries in the world. The working-age population in Finland is concentrated in the big cities and surrounding areas, while a large proportion of the older adult population lives in sparsely populated areas. This brings large economic and logistical challenges because of the great distance between people and services. They face the same health challenges as in the United States, including a high risk for medication-related problems resulting from multiple, excessive, or unnecessary medications.

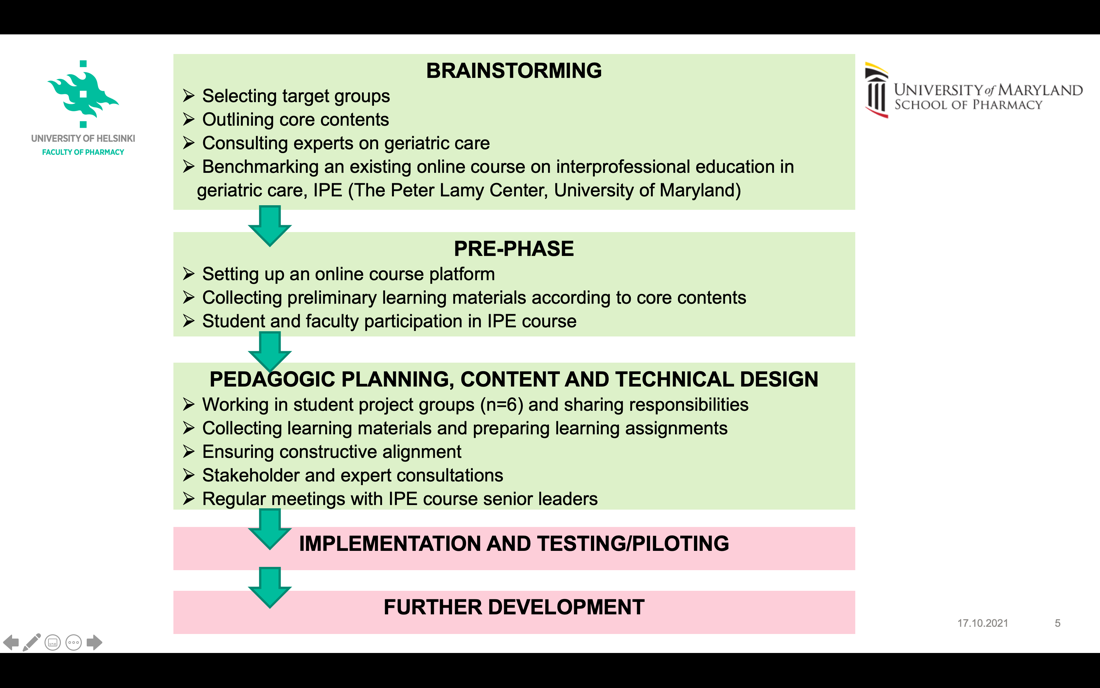

As a result of participating in this IPE course, our Finnish colleagues desire to tackle the growing need of geriatric care expertise in health care, aiming to promote an interprofessional mindset and lifelong learning by offering a comprehensive online course with a special reference to applied geriatric pharmacotherapy. The course is being designed following the principles of constructive alignment, first introduced by John Biggs (1996) (Figure 2). Constructively aligned teaching allows the student to construct meaning in the learning activities and to build new knowledge upon what they already know. Aligned teaching is based on well-defined learning outcomes, and all teaching activities and assessment criteria are designed to support the student in achieving those objectives. In line with the teaching model employed at University of Helsinki, our Finnish colleagues are using the principle of “all teach, all learn”–meaning that all course participants, including students, contribute to teaching, that is, they teach each other and learn from each other. According to the principle of “all teach, all learn,” students play an integral part in developing the teaching and the delivery methods that support learning from each other, as highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Phases of the development process of an interprofessional online course.

Development of this interprofessional online course during the brainstorming phase included collaboration with experts on geriatric care, including faculty at UMB, and benchmarking the international IPE course. During the pre-phase, course developers collaborated with pharmacy students participating from Finland and other European universities, as well as senior leaders of the IPE course, in order to receive practical information on good practice in the content and implementation of this type of online course. During the pedagogical planning phase, the course developers ensured that the principles of constructive alignment were followed and that implementation is student-oriented. To do this, a group of 20 fourth-year pharmacy students assisted with course creation and they held regular meetings with IPE course senior leaders.

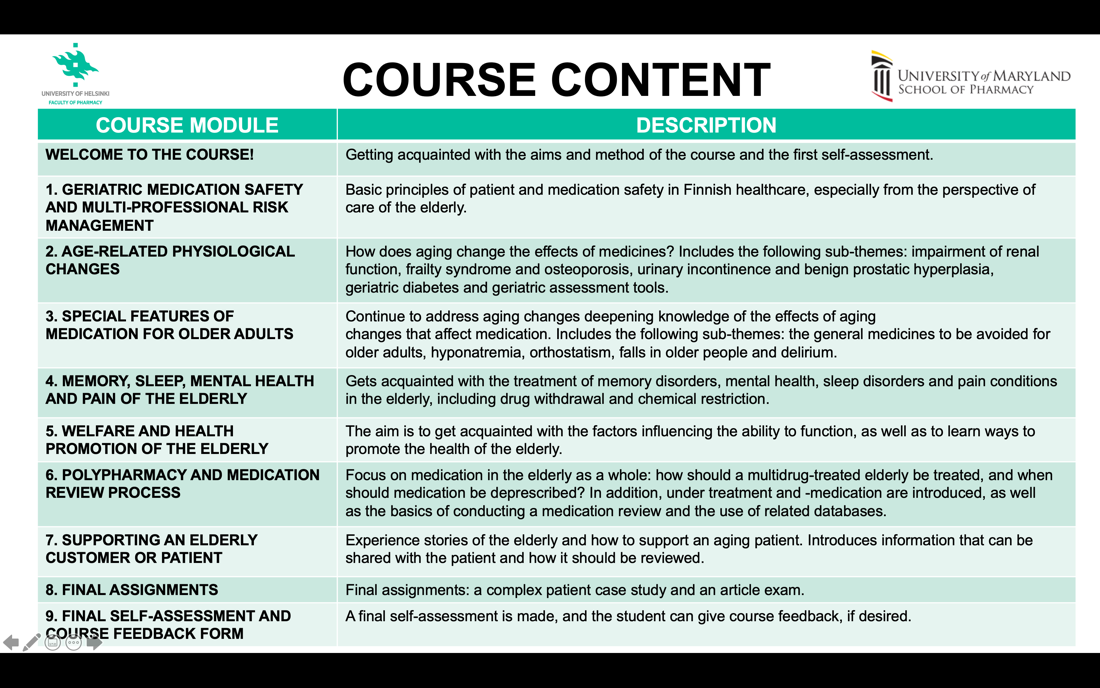

Through the principle of cooperation and learning by doing, course topics and content have been divided into modules, as shown in Figure 3. At this point, the topics and the content have been created following the most important themes within geriatric pharmacotherapy that pharmacists need in their work. Later, the content will be expanded to include areas of expertise necessary for physicians, nurses, and practical nurses.

Figure 3. Planned content of the online course.

Conclusion

Out of the challenges that COVID-19 pandemic introduced, opportunities were born. Lessons learned included those about our neighbors and their ability to participate, including problems using computers and smartphones due to changes in mobility, dexterity, and vision. “Faceless” learning environments that lack a sense of community can be mitigated by asking everyone to turn on their cameras so that participants can feel almost the same togetherness as a face-to-face learning environment. In the end, we appreciate the opportunity to participate in the Silver Linings faculty showcase and hope our story offers inspiration to others seeking to construct powerful IPE experiences for students .

References

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347–364.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC). (2016). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Retrieved April 8, 2022 from https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf

McCutcheon, L. R., Haines, S. T., Valaitis, R., Sturpe, D. A., Russell, G., Saleh, A. A., … & Lee, J. K. (2020). Impact of interprofessional primary care practice on patient outcomes: A scoping review. SAGE Open, 10(2), doi: 2158244020935899.

NIH. (2016). World’s older population grows dramatically [News release]. Retrieved June 7, 2022 from https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/worlds-older-population-grows-dramatically