Online and Blended Learning Planning Matrices

Mary L. Slade and Patricia Westerman

Mary L. Slade, Professor of Early Childhood Education,Towson University | mslade@towson.edu

Patricia Westerman, Assistant Provost for FACET, Towson University | pwesterman@towson.edu

Due to the unprecedented and unexpected impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic on higher education teaching and learning, higher education faculty were thrust into remote teaching with very little if any preparation. In fact, most faculty barely had time to adapt their traditional courses to remote learning, much less transform them into effective remote platforms supported by best practices in instructional design and technology (Dill, Fisher, McMurtie & Supiano, 2020). The consequence was most faculty who were already in the middle of an academic semester began to translate existing face-to-face courses to remote learning without expertise or experience.

The continuation of remote course delivery in the subsequent academic year gave rise to rapid development and delivery of professional learning initiatives across university campuses to support faculty in their continued efforts. Foremost, universities needed to provide faculty access to new knowledge and skills necessary for technology-driven platforms. Specifically, the remote course development process includes awareness of online and blended course delivery formats, platforms, models, pedagogies, and best practices (Lederman, 2020).

To support faculty’s development of online and blended coursework at Towson University, professional learning workshops promoting best practices were provided to more than 550 faculty. Full- and part-time graduate and undergraduate faculty participated in one of five one-week synchronous or two-week asynchronous workshops on online and blended course development. In addition to providing best practices in instructional design, pedagogies, assessment, and course development, the workshop content emphasized the use of a series of unique matrices designed to assist faculty in course planning. Further, faculty peer-mentors offered guided practice in using the matrices to participants and exemplary planning was spotlighted across academic departments and colleges. Lastly, instructional designers facilitated discussion board participation to address individual and common questions that arose.

What?

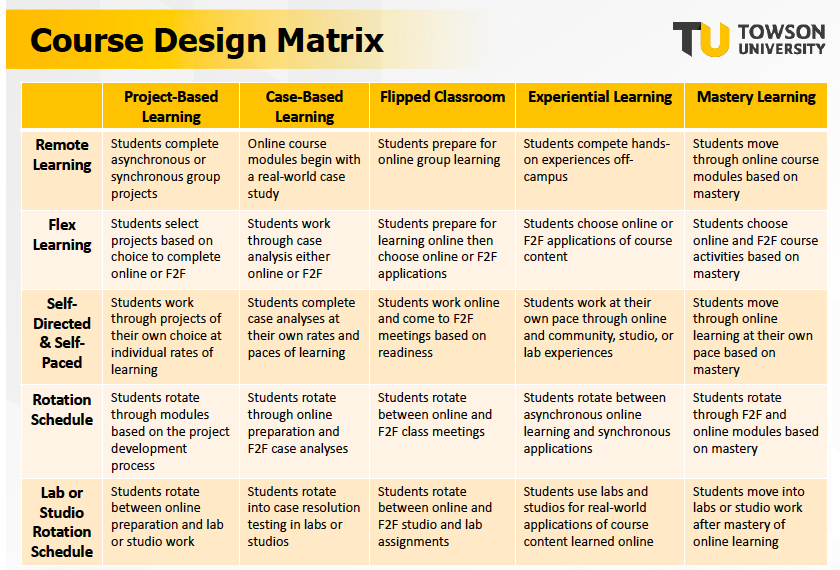

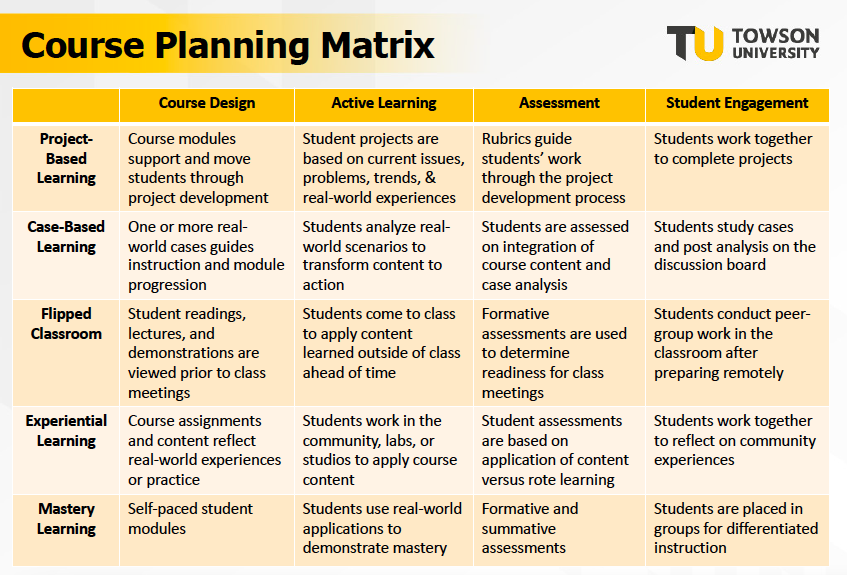

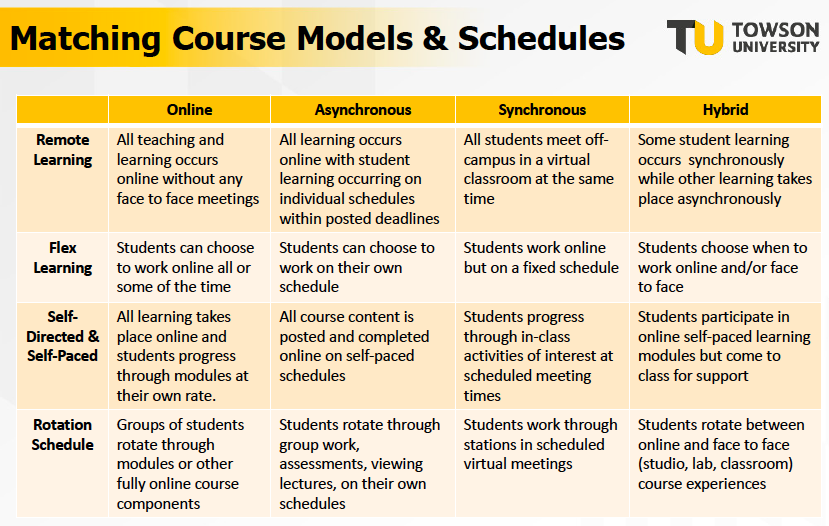

A five-step course development process was modeled for faculty. Several steps of the process included the use of the planning matrices developed by a faculty member and teaching fellow. The course development process included the following processes: (1) Determine course platform [e.g., synchronous versus asynchronous]; (2) Determine technology models [e.g., remote learning, rotation schedule, flex learning]; (3) Align models and platforms (matrix 1); (4) Determine course pedagogy that aligns with best practices in instructional design (matrix 2); and (5) Plan course instruction based on technology models and pedagogy (matrix 3). The matrices can be found in the Appendix.

So What?

Whether intentional or due to extenuating circumstances, the transformation of traditional face-to-face university course delivery to online or blended formats is an arduous task for most university faculty who do not possess the expertise in instructional technology or design to support this process. A blended solution is not realized simply by translating the curriculum to a technology platform. Similarly, requiring students to read online text or view a video does not result in a hybrid course of study. In fact, to do so will only serve to create a “technical hodgepodge” (Tipton, 2020).

The quality of all teaching and learning is the cornerstone of higher education efficacy. Student recruitment, retention, and matriculation is correlated with the quality of the academic programs and the performance of the faculty who deliver them. Further, consistency of teaching and learning across coursework is critical to institutional success in the provision of quality academic experiences. Although the needs of current and future students indicate a trend toward virtual learning, the expectation remains for high-quality academic programming. Thus, faculty must be well versed in the most effectual means for developing and implementing online and blended courses to deliver coursework that meets the academic standards of the institution, the discipline, and profession.

An expanding body of professional literature regarding instructional design in online and blended courses offers guidance on the work of individual faculty, programs, and colleges in higher education. For example, McGee & Reis (2012) conducted a review of the literature to produce a synthesis of best practices in blended courses in higher education. A qualitative meta-analysis resulted in a common set of principles and best practices in design, pedagogy, technology utilization, student assessment, and course delivery. The authors build a case for the application of best practices to increase the likelihood of successful utilization of consistent practices and processes that support course effectiveness.

While neither the format of course design nor mode of instructional delivery alone guarantees the quality of teaching and learning, both knowledge of best practice and innovative applications can increase the prospect of effectiveness of online and blended courses. With thorough contemplation, planning, and execution, course transformation makes use of new technologies, pedagogies, and design components consistent with online and blended modalities. The course development process includes awareness and appropriate application of online and blended course delivery formats, platforms, models, pedagogies, and best practices.

The rationale for the provision of faculty workshops at Towson University was the need to support faculty in their rapid shift to remote teaching, as decreed by the university administration. Thus, it was determined that teaching during the pandemic would be enhanced with the establishment of intensive summer workshops. As the staff and affiliated faculty of the Faculty Academic Center for Excellence at Towson (FACET) prepared the professional learning for faculty, several principles guided the workshop development and implementation. Foremost, we recognized the need to begin at the point where most faculty found themselves in terms of knowledge and skill acquisition in teaching online and blended courses. Similarly, we needed to know what it was the faculty already knew about the course transformation process. Of equal concern was determining what faculty needed to know to be successful and to emulate best practices. Two final principles guided the development of professional learning workshops: the best way to deliver new information effectively, and how best to reach faculty to teach them without overwhelming them.

Now What?

Although most higher education campuses are returning to face-to-face teaching and learning, it behooves faculty to ask themselves what worked when teaching remotely and how do they carry forward the best aspects of the experience. Faculty expanded their awareness of pedagogies such as case-based or mastery learning, for example. They are now poised to explore how to use the effective approaches to learning in face-to-face platforms. Further, faculty learned technology models that may be useful in a blended course, such as flex learning which allows students to choose the schedule for learning (McGee & Reis, 2012). In fact, flex learning may address the needs of adult learners in graduate degree programs. These and other questions should be asked and answered by individual or collective groups of faculty in various disciplines.

Those tasked with faculty professional learning and instructional support wonder what continued training faculty need to maintain proficiency in blended course development and implementation. Planning of faculty development approaches, including workshops, communities of practice, and consultation activities, will reflect this objective.

As faculty continue to develop blended coursework, what new considerations exist as lessons learned from their recent experiences? The matrices developed for the summer 2020 online and blended teaching workshops will continue to form the foundation of all faculty development activities related to teaching. There will be an intentional focus on the importance of pedagogy as a scientific and evidence-based endeavor.

Informing Teacher Education Preparation

In addition to higher education coursework, the pandemic caused Pre-K-12 classrooms everywhere to move to virtual meetings. As universities prepare future educators, we must consider how to provide prospective teachers the knowledge and skills necessary to develop and deliver blended instruction. Additionally, research should focus on how blended instruction impacts and meets the unique needs of young learners. Finally, we should determine how blended instruction allows highly capable young learners to access post-secondary coursework while attending secondary schools.

References

Dill, E., Fischer, K., McMurtrie, B., & Supiano, B. (2020, March 6). As Coronavirus spreads, the decision to move classes online is the first step. What comes next? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from https://www.chronicle.com/article/As-Coronavirus-Spreads-the/248200

Lederman, D. (2020, March 18). Will shift to remote teaching be boon or bane for online

learning? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/18/most-teaching-going-remote-will-help-or-hurt-online-learning

McGee, P. & Reis, A. (2012). Blended course design: A synthesis of best practices.

Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(4), 1-22.

Tipton, S. (2020). 5 steps to a successful blended learning strategy. Learning Rebels Fighting the Good Fight. Retrieved March 15, 2022 from https://learningrebels.com/2020/05/06/5-steps-to-a-successful-blended-learning-strategy/

Appendix

Planning Matrices

Matrix One.

Matrix Two.

Matrix Three.