The Struggle is Real: Assessing Reading Assignments

Ming C. Tomayko

Professor, Department of Mathematics, Towson University | mtomayko@towson.edu

How do I hold students accountable for reading assignments? I have been grappling with this question for years in my elementary mathematics methods course. In fact, I tried three different approaches, yet none were successful.

First, I used the discussion board feature on Blackboard, our learning management system. I placed students into small groups and asked them to: a) respond to a prompt about the assigned chapter and b) respond to a peer’s post. Unfortunately, this format was frustrating for both me and my students. While some students took the time to carefully read the chapter and respond to the prompt thoughtfully, most students wrote very brief, superficial responses. Another issue was that some students did not post responses to the prompt in a timely manner. They may have procrastinated, or they may have struggled with crafting a response. Either way, it meant that their group members had no posts to respond to.

Next, I used reading quizzes given at the beginning of our class meetings. These were meant to be quick assessments covering the big ideas from the reading assignment. However, the anxiety was palpable as soon as my students entered the classroom. “From the entire chapter, what might the question be?” they wondered. To reduce their stress, I allowed them to answer just one of three possible questions. This format made it obvious who had read the chapter and who had not, though it was harder to distinguish if students had read the entire chapter or just a portion of it. I intended for the quizzes to take about 10 minutes, but I also did not want to rush students who were still writing. The result was that the quizzes took up much more class time than I would have liked, and students were mentally drained before we even started the class activities.

Then, I used written reflections where students responded to a set of prompts about the assigned reading. The entire reflection paper was expected to be 1-2 pages in length and demonstrate that the student had read the chapter. Since written reflections did not have the same issues that discussion boards and quizzes had, I used this method for several years. However, it seemed that students found the written reflections tedious and insignificant. For example, there were often fewer reflections submitted on days when big assignments were due.

In Fall 2020, my typically face-to-face elementary mathematics methods course changed to fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Class sessions were synchronous Zoom meetings twice a week. This shift in modality caused me to rethink class activities and assignments. One significant change was the use of Google Slides for class notes. Keeping students engaged during online courses was crucial, so I switched from PowerPoint to Google Slides so that students could interact with and edit the class notes. I found Theresa Wills’ website (https://www.theresawills.com) particularly helpful because it contained a variety of Google Slide templates for me to use and modify.

I also changed how I handled reading assignments. I decided that students would discuss the readings in breakout groups during class. I hoped this format would give all students an opportunity to participate in the discussion without taking up an inordinate amount of class time. On the first day of class, students created a slide about themselves so that I could gauge their comfort and familiarity with editing Google Slides. They practiced making text boxes, uploading images, inserting shapes, and adding comments or notes. During class, I previewed the upcoming reading assignment by highlighting key topics and providing a list of guided reading questions (Figure 1).

![Screenshot showing example questions. It reads: "Previewing Chapter 11: Developing Strategies for Addition and Subtraction Computation. [Bullet] What are inverted strategies? Why are they beneficial? How do we encourage inverted strategies? [Bullet] What is computational estimation? Why is it useful? How do we teach it? Which computational estimation strategies do you use? [Bullet] Which common challenges or misconceptions were new to you? Which of the 'how to help' suggestions seemed most useful? [Bullet] How does the Graham Fletcher video help you make sense of the ideas in Chapter 11?"](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/731/2022/07/tomayko_fig1-2.png)

Figure 1. Example of guided reading questions.

At the next class meeting, I created breakout rooms in Zoom and used the automatic assignment option to evenly distribute the students. In the slide deck, I included a slide for each breakout room (Figure 2). The slide had spaces for students to list their names and record their discussion of selected reading prompts. I expected all group members to discuss the reading prompts, record ideas on the team slide, and share items from their slide when we reconvened. After class, I reviewed the team slides and determined a score based on the scope and quality of the content.

After numerous attempts at getting my students to read the course text, I finally found a method that worked. The students appreciated the guided reading questions and their reading comprehension improved. In previous semesters, students were hesitant to speak up during whole class discussions and typically, the same couple of students would volunteer to respond. In the new format, students got their ideas validated in the breakout rooms and felt more comfortable sharing those ideas with the whole class. Students seemed more motivated to stay on top of the reading assignments so they could contribute to the breakout room discussions. Completing the reading assignment and understanding the key concepts also meant that students could engage more meaningfully in the class activities.

Figure 2. Example of completed breakout room slide.

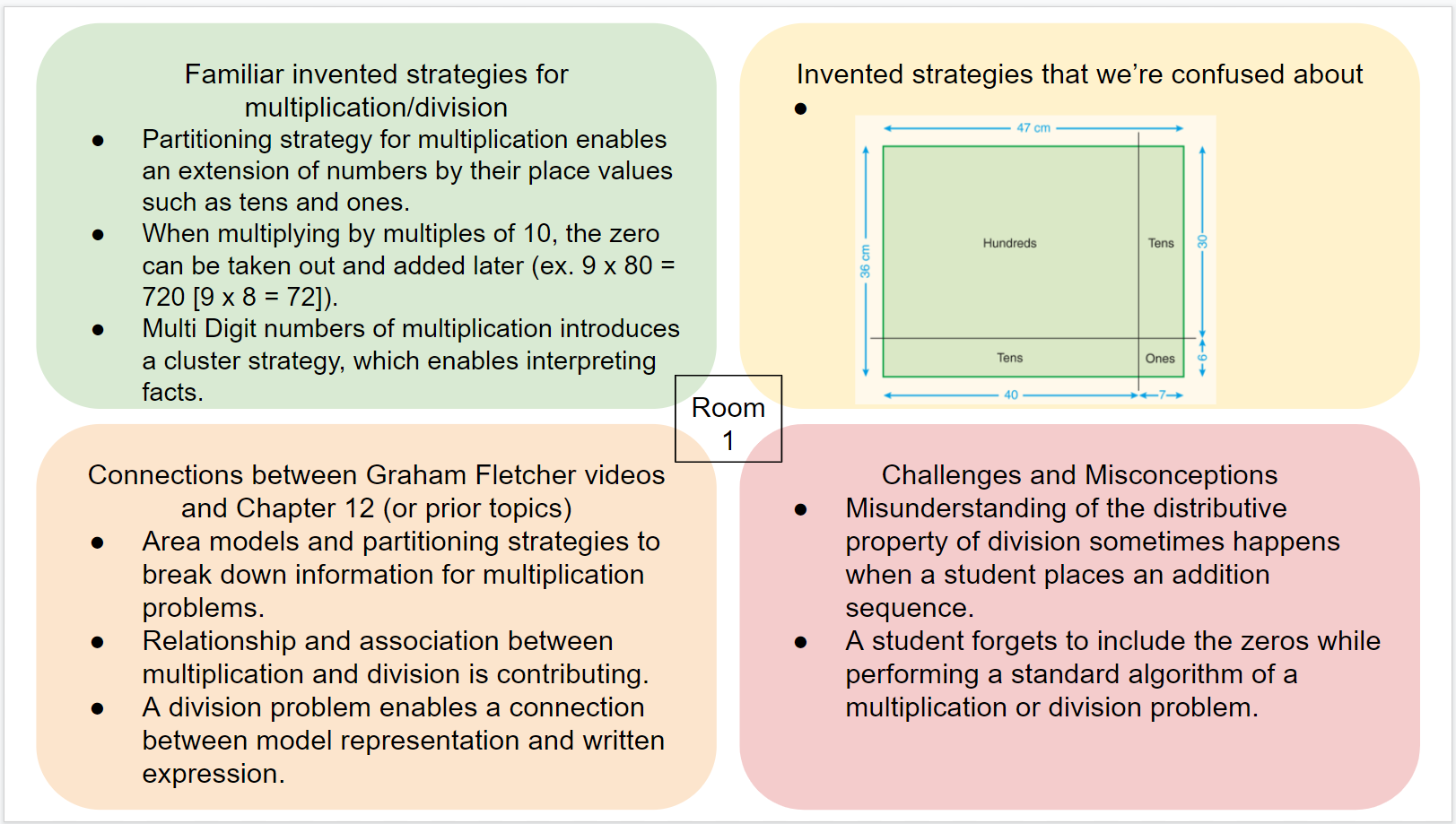

There were other benefits as well. When students had submitted written reflections, I did not know what they wrote until after class was over. If they misinterpreted a section of the text, I was unaware and unable to address it promptly. Students were usually too embarrassed to ask questions, often assuming that they were the only one who did not understand something. With the use of breakout rooms and Google Slides, I knew immediately which topics students were comfortable with and which they were unsure about (Figure 3). Students realized that their peers had similar areas of confusion and I could then adjust my planned activities to respond to these issues. Also, I could easily monitor group productivity by watching text fill up on the slides. If necessary, I could pop into a breakout room to provide support. This was a vast improvement to face-to-face settings, where I had difficulty knowing what was going on in every small group discussion. Even if I walked around and observed each group, I only caught bits and pieces.

Figure 3. Example of breakout room slide with topics of confusion.

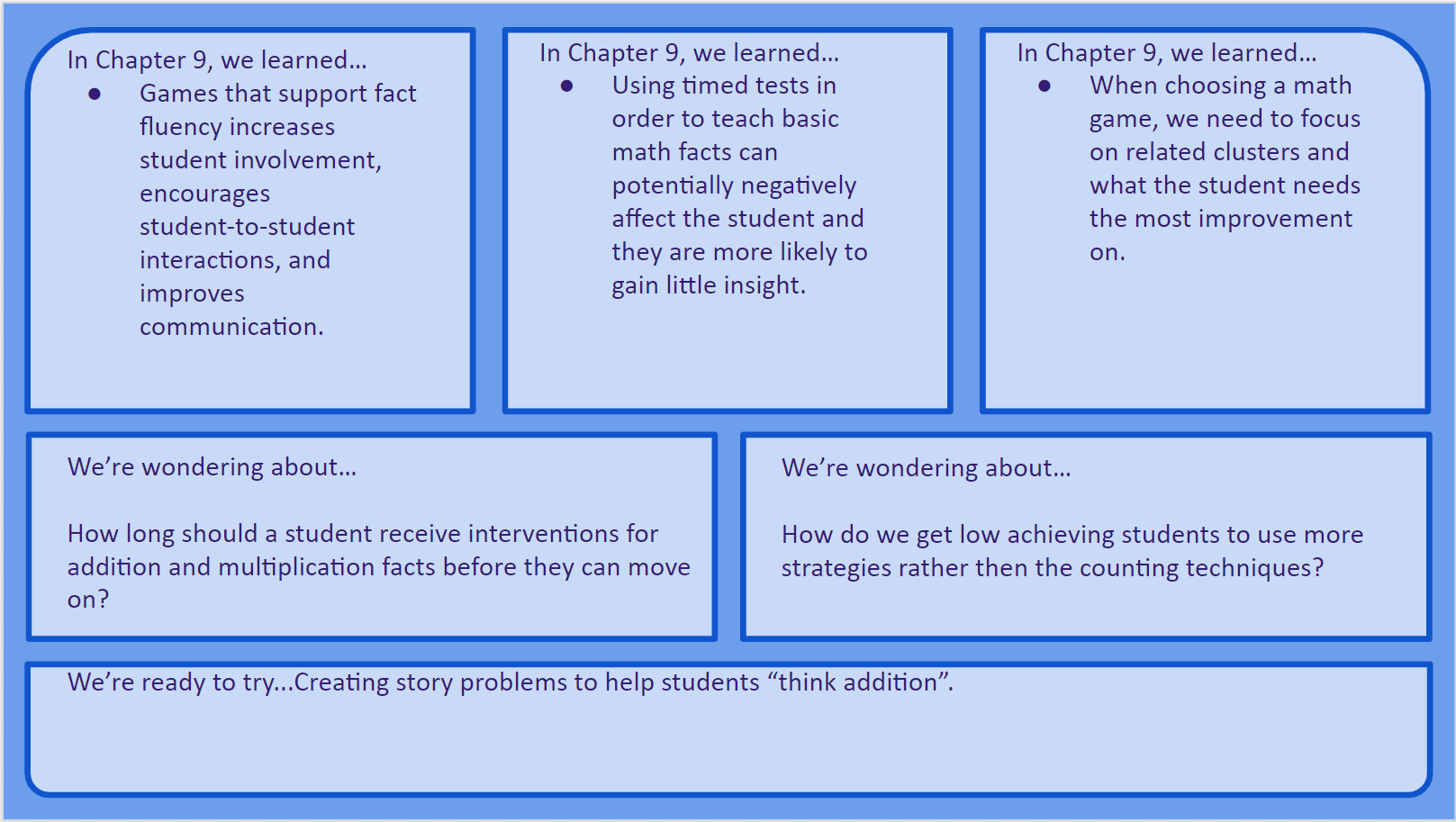

I made sure to vary the slide templates and the structure of the discussion questions from week to week to maintain a high level of student interest. Sometimes the discussion questions stemmed from the reading itself. Other times I got inspiration from Mathematics Formative Assessment: 75 Practical Strategies for Linking Assessment, Instruction, and Learning (Keeley & Tobey, 2011). I found the 3-2-1 technique (p. 194), the “I used to think…but now I know” strategy (p. 109), the point of most significance (p. 155), and the muddiest point (p. 132) to be particularly well-suited for my purposes. In the slide shown in Figure 4, I asked students to identify three things they learned, two things they were wondering about, and one thing they were ready to try. As students worked in their breakout rooms, I kept track of their progress and made notes about which groups I would ask to share when we came back together as a whole class. It was important to me that students had an opportunity to see and hear what their peers in other breakout rooms wrote. The process of working in small groups and sharing out with the whole class seemed more effective and engaging than having me review the main ideas from the reading.

Figure 4. Example of a 3-2-1 slide.

Overall, the use of guided reading questions, breakout rooms, and Google Slides worked well as a means of holding my students accountable for reading assignments. There was one minor problem that arose. In the beginning of the semester, I told students that once they got in their breakout rooms, they should grab a slide and start typing. However, sometimes students from different breakout rooms started typing on the same slide. Luckily, this was an easy fix. From then on, I labeled the slides with room numbers and there were no more mix-ups.

In Fall 2021, we returned to campus and resumed face-to-face instruction. Nevertheless, I continued using Google Slides so that my students could interact with the class notes. I still provided guided reading questions even though our small group discussions were no longer in Zoom breakout rooms. Whenever students worked in groups, I included slides in the slide deck for them to use. This method of documentation not only allowed me to see what they had accomplished, but it also provided a lasting record for students.

I extended the use of Google Slides to my math content courses as well. While this may seem like a minor change, I feel that it has given students more control over their learning. In the past, students asked me to post the PowerPoint slides before instead after class. I hesitated because I worried that students would preview the slides and not come to class. When I began using Google Slides, I posted the link in Blackboard the day before class. I was pleasantly surprised that students did not use this as a reason to skip class. In fact, I feel that students came to class more prepared when they knew what I had planned. My classroom had computers that students could use but most preferred to bring their own laptop or tablet. If students were taking notes and I had moved on before they were ready, they could easily go back to the slide they needed. When we did practice problems, students could enter their solutions directly into the class slides. I also noticed that students returned to the slides after class more frequently than when I used PowerPoint. For example, when students worked on homework or studied for a quiz, they knew exactly which slide to pull up. Of course, there were downsides to giving all students edit rights. There were a few instances where slides were accidentally deleted. Fortunately, Google Slides has a “recover” feature that resolved the issue. After each class, I also switched the slide setting from edit to view to preserve what we had done in class.

We often get set in our ways and find it difficult to change what we do or how we do it. I had always made tweaks to my PowerPoint slides, class activities, and course assignments, but I dreaded making drastic changes. The COVID-19 pandemic forced me out of my comfort zone and as a result, helped me improve my instructional methods. I know nothing is ever perfect so I am confident I will continue to fine-tune my reading prompts, Google slides, and other aspects of my courses. For now, I am pleased that I could not only continue to teach, but also facilitate community-building in a virtual classroom during a challenging and stressful time in our lives.

Reference

Keeley, P. & Tobey, C. R. (2011). Mathematics formative assessment: 75 practical strategies for linking assessment, instruction, and learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Mathematics.