3

Karen MacDonald

Mohawk College

Abstract

This chapter aims to deepen an educator’s understanding of the value of technology in kindergarten classrooms and offers practical ways in which technology can be integrated into kindergarten programs. Although reference is made to Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, information will be beneficial to readers outside of Ontario who have similar education priorities. The integration of technology is discussed with specific support from the Ontario Ministry of Education’s (OME) (2016) Kindergarten Program publication. This establishes the basis for the exploration of how technology can support enhancements in pedagogy, curriculum and assessment. Pedagogical approaches that are explored include: educators as co-learner, learning through exploration, play and inquiry, pedagogical documentation and collaborative inquiry (OME, 2016). Contributing factors to a kindergarten educator’s reluctance to infuse technology into their classrooms are also reviewed. Specific examples of applications are shared to assist educators in exploring ways in which they can enhance their pedagogy, curriculum and assessment through the use of technology. The importance of providing opportunities for children to engage in technology-enhanced learning experiences to help develop skills that will prepare them for the future is reinforced. Further research is required in order to assist us, as educators and administrators, to reflect upon and re-evaluate the quality of support we are offering to our kindergarten teachers, our beliefs about the pedagogy of play and what we value as substantiation of a child’s learning.

Keywords: digital play, early childhood education, inquiry-based learning, kindergarten curriculum, kindergarten pedagogy, play-based learning, technology

Introduction

Children are our youngest digital natives, born into a world infused with technology. It is a familiar and natural occurrence in their everyday lives. The pedagogy that drives kindergarten programs in Ontario supports the integration of technology into classrooms as an authentic extension of young students’ learning (OME, 2016). Despite numerous studies supporting the prevalence of technology in a child’s life, as well as it being the chosen means for many children to express themselves and share their thinking, many kindergarten educators are hesitant to embrace the addition of technology into their teaching practice (Palaiologou, 2016). Early Childhood Educators (ECEs) and Kindergarten teachers have a responsibility to gain a deeper understanding of the importance of incorporating technology into the pedagogy and curriculum that supports our earliest learners.

Background Information

Within Ontario’s kindergarten classrooms, pedagogy and curriculum are driven by the OME (2016) document The Kindergarten Program. This document outlines the changes in pedagogical approaches from traditional educator-lead pedagogy to one that is learner centred (OME, 2016). It stresses the importance of developing a curriculum that supports each child as competent, curious and capable of complex thinking and the need to provide learning opportunities that prepare students for an ever-changing world (OME, 2016). It is imperative for educators to be mindful that our role is to prepare students for the future. There has been a pedagogical shift from teacher-lead classrooms with theme-based curriculum to one that supports play and inquiry-based learning driven by the interests and abilities of students. Edwards (2013) argues that we need to bridge the gap between how children naturally engage with technology outside of the classroom and our understanding of the pedagogy of play as the foundation of our Kindergarten programs.

Students in our kindergarten classrooms will need to work in a world where technology will advance at a rate we cannot yet comprehend (Prensky, 2010). It is argued that educators need to take a closer look at opportunities to make digital play an integral piece of early years pedagogy (Nolan & McBride, 2014) and that educators’ current beliefs about play-based learning impedes the practice of embracing technology as a fundamental component of an early learning environment (Palaiologou, 2016). Educators argue that the hesitancy is due to accessibility, where every child may not have equal means to access technology. Other factors influencing the lack of willingness to embrace technology in the early years are the beliefs that it causes social isolation and promotes a sedentary lifestyle in children (Palaiologou, 2016). Some educators believe that a child’s authentic hands-on experiences within their natural environment are impeded when technology is introduced and that they become more isolated learners (Palaiologou, 2016). Teachers’ efficacy, values and beliefs about technology and the lack of professional development and support (Edwards, 2013; Palaiologou, 2016) are additional barriers. The pedagogical freedom for educators to make decisions about when and where to use technology to support their students’ learning have also been found to impede the willingness for educators to embrace technology as an integral component of their pedagogy (Edwards, 2013).

Influencing Pedagogy

Pedagogical approaches that guide the kindergarten curriculum include: educators as co-learner, learning through exploration, play and inquiry, pedagogical documentation and collaborative inquiry (OME, 2016). The first two approaches will be further explored with the focus on how technology can support and enhance these initiatives within the kindergarten classroom. The latter two will be explored under the heading of Assessment.

Educators as Co-learners

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the interests, skills and abilities of their learners, educators are moving from the role as the keeper of all knowledge to the role of head learner in kindergarten classrooms (OME, 2016). Educators must focus on questioning, guiding, coaching and providing context (Prensky, 2010). Students today want an educational leader who will respect their ability to learn beyond limitations and to provide opportunities to engage with technological tools to build knowledge and relationships (Prensky, 2010). This is most successfully accomplished by kindergarten educators through the facilitation, intentional planning of and engagement in children’s play experiences. Digital applications can be used to share consistent feedback between student and educator, offer tools to collect documentation of students’ learning, and to respectfully share resources to increase students’ self-efficacy and motivation.

Learning Through Exploration, Play and Inquiry

Inquiry based learning occurs when educators embrace the natural curiosity of their learners. In kindergarten classrooms, children should be encouraged to ask questions and wonder about topics that they are interested in to uncover curriculum expectations. Through consistent play, inquiry and free exploration, children gain 21st century skills such as critical, creative and complex thinking, innovative design, problem solving and collaboration (OME, 2016). Prensky (2010) also supports this necessity stating that our pedagogy should reflect a strong support of such skills as finding information, manipulating that information to make sense of it, creating new ideas and solving problems in unique ways. Similarly, Fullan (2013) states that “the interest in and ability to create new knowledge and solve new problems is the single most important skill that all students should master today” (Fullan, p. 24).

The incorporation of technology is most successful when it is paired with a pedagogy that supports the intentions of its use (Prensky, 2010). Many times, the pedagogy of play is seen as a separate entity from the use of technology, which instead, is viewed as a tool to support the skills of learners (Edwards, 2013). Digital Play should be a naturally occurring, integral part of a classroom setting, not a separate learning area. When given the opportunity, children can merge digital technology into their play in ways that “expand the range of identities they explore and the tools and practices with which to explore them” (McGlynn-Stewart, 2019, p. 52). Through inquiry, based on naturally occurring interests of children in the classroom, students are able to solve problems to gain a greater understanding of their world. When educators stand aside and let the learning happen, children achieve greater skills because they have been given the opportunity to seek answers on their own or through collaboration with their peers, rather than being taught the solution first (Brown, P.C. Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M. A., 2014). Palaiologou (2016) argues that we need to provide digital means for children to extend possibilities within their play in order to accomplish this task.

Application.

Apps such as Khan Academy Kids (Khan Academy, n.d.), National Geographic Kids (National Geographic, n.d.) and Explain Everything (Explain Everything, n.d.) provide interactive online environments supporting students’ inquiry.

Influencing Curriculum

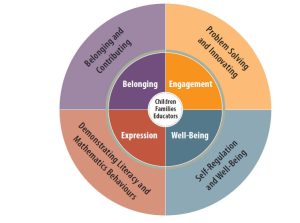

The Kindergarten Program (OME, 2016) uses the following four frames to help organize how we think about children’s thinking and the assessment of their learning: Belonging and Contributing, Self-Regulation and Well-Being, Demonstrating Literacy and Math Skills and Problem Solving and Innovating (OME, 2016). Technology positively influences all frames, but the latter frame will be focused on in this section.

Problem-solving and Innovating

In this frame, children demonstrate their unique ways of solving problems or relating to ideas by exploring things they are naturally curious about (OME, 2016). Students may ask questions, test theories and engage in analytical thinking while educators design a learning area that includes various tools that allow children a choice in what methods would best support the development of these skills. Educators offer opportunities for collaborative learning and should create spaces where children can express their thinking and learning. This is supported through the technology-related expectations that are stated with the Kindergarten Program (OME, 2016) including: using technology to solve problems independently or with others, plan, question, construct new knowledge and analyze and communicate thinking (OME, 2016).

The integration of technology may support a child’s understanding of concepts in literacy and math through practical application, problem-solving and collaboration (Palaiologou, 2016). Researchers have also found that engaging in digital game-based programs promotes collaboration, problem-solving, communication and experimentation among kindergarten students and suggest that allowing students to behave more autonomously in game play, leads to higher engagement and motivation (Nolan & McBride, 2014). Practical examples of applications that support the enhancement of problem-solving and innovation are listed below.

Application.

An open-ended app such as 30 Hands (30 Hands Learning n.d.) enables children to document their thinking by way of drawing pictures and recording voice to write their own stories. This app provides students a means to share their thoughts beyond the limitations they would have displayed without the use of digital technology (McGlynn-Stewart, Brathwaite, Hobman, Maguire & Mogyorodi, 2018). The 30 Hands app also allows children to save and revisit their work allowing reflection on their learning and the deeper complexity of their thinking (McGlynn-Stewart et al., 2018). Similarly, apps such as Thinglink (Thinglink, n.d.) and Shadow Puppet Edu (Seesaw Learning Inc. (n.d.) allow students to capture, organize and communicate their thinking in unique and interesting ways. An app such as Gamestar Mechanic (Gamestar Mechanic, n.d.) allows early learners to begin developing skills in coding and game creation and an app such as Blokify (Blokify, n.d.) can help students as young as 4 or 5 years to design, create, problem-solve and collaborate within a Makerspace environment.

Influencing Assessment

Learners today think, communicate and use different means to share what they know in ways that are different from students in past decades. Donovan, Bransford and Pellegrino (2002) state that, with our newest learners, we must move beyond traditional testing to incorporate understanding through frequent formative assessments that make learning visible (Donovan et al., 2002). It is imperative that we enhance our traditional methods of assessment with technology-based assessment in order to provide more enriched feedback to our learners.

Pedagogical Documentation

Pedagogical documentation is defined as the gathering of and analysis of evidence of a student’s thinking (OME, 2016). Educators aim to make a student’s learning visible to both the child and family, and use knowledge gained from observations to drive further programming. Within kindergarten classrooms, pedagogical documentation provides the means to which assessment for, as and of learning is made (OME, 2016). In a play-based environment, educators should gather frequent and meaningful observations of children that incorporate the child’s voice so that reflections can be made about how a child interprets, understands and interacts with their world (OME, 2016). Pedagogical documentation, which technology has the capability to enhance, provides a means of formative assessment of a child’s learning and, in turn, should drive future curriculum planning (Rintakorpi, 2016).

Application.

Apps that allow students to organize and record their process of learning (as described above) captures visible documentation that can be saved, shared, revisited and revised which allows children to develop an in-depth understanding of curriculum. These applications provide a diary of the progression of a child’s journey in reaching outcomes; a story of each child’s learning.

Reflective Practice and Collaborative Inquiry

In early learning environments, the relationship between parent, child and educator helps build an important foundation for a child’s learning. Educators both independently reflect on and collaborate with peers, families and children about the pedagogical documentation they have collected OME, 2016) in order to learn from the experiences of each student. By including parents in these conversations, an educator gains insight into a child’s previous knowledge and experiences at home. Research has shown that using documentation empowers educators and nurtures their relationship with children and parents by providing an important tool for communicating and understanding a child’s perspective (Rintakorpi, 2016).

Application.

Apps such as Brightwheel (Brightwheel, n.d.) and Storypark (Storypark, n.d.) provide a platform to capture a child’s learning through pedagogical documentation that can be shared and securely accessed by children and their families.

Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Although it is supported through expectations laid out by our Ministry of Education (2016) in The Kindergarten Program publication, many kindergarten educators remain reluctant to embrace technology as an integral part of their pedagogy and curriculum. One of the most prevalent factors contributing to this is an educator’s belief about the pedagogy of play and what they value as evidence of a child’s learning. Palaiologou (2016) believes there is a need to challenge the current ideology of what we believe about a child’s play and that only then can educators embrace technology within their kindergarten classrooms. The addition of technology-based pedagogy into pre-teaching programs as well as increased professional development for current educators could close the gap between what educators believe about how a child learns and understanding how technology does not hinder but enriches the quality of this learning. Further research is needed to examine the relationship between traditional and digital play as well as the influence that digital technology has on a child’s learning experiences within play and inquiry-based environments.

References

Blokify. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from http://blokify.com

Brightwheel. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://brightwheel.com

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Learning is misunderstood in Make it stick (pp. 1-22). Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Donovan, M.S, Bransford, J. D., & Pellegrino, J.W. (2002). Key findings in How people learn: Bridging research & practice (pp. 10-24). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Edwards, S. (2013). Digital play in the early years: a contextual response to the problem of integrating technologies and play-based pedagogies in the early childhood curriculum. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(2), 199-212. doi:10.1080/1350293x.2013.789190

Explain Everything. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://explaineverything.com

Fullan, M. (2013). Pedagogy and change: Essence as easy. In Stratosphere (pp.17-32). Toronto, Ontario: Pearson

Gamestar Mechanic. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://gamestarmechanic.com/

30 Hands Learning. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from http://30hands.com/

Khan Academy. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/kids

McGlynn-Stewart, M., Brathwaite, L., Hobman, L., Maguire, N., & Mogyorodi, E. (2019). Open-Ended Apps in Kindergarten: Identity Exploration Through Digital Role-Play. Language and Literacy, 20(4), 40-54. doi:10.20360/langandlit29439

Muis, K. R., Ranellucci, J., Trevors, G., & Duffy, M. C. (2015). The effects of technology-mediated immediate feedback on kindergarten students’ attitudes, emotions, engagement and learning outcomes during literacy skills development. Learning and Instruction, 38, 1-13. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.02.001

National Geographic. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2016). The kindergarten program. [Web page]. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/kinderprogram.html

Palaiologou, I. (2016). Teachers’ dispositions towards the role of digital devices in play-based pedagogy in early childhood education. Early Years, 36(3), 305-321. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1174816

Prensky, M. (2010). Partnering. Teaching digital natives. Partnering for real learning (pp. 9-29). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Rintakorpi, K. (2016). Documenting with early childhood education teachers: pedagogical documentation as a tool for developing early childhood pedagogy and practises. Early Years, 36(4), 399-412. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1145628

Seesaw Learning Inc. (2014, June 26). ‘Shadow Puppet Edu. [Software application]. Retrieved from https://apps.apple.com/us/app/shadow-puppet-edu/id888504640

Storypark. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.storypark.com/ca/

ThingLink. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.thinglink.com/