Learning Theories and Models

1

Ilana Zigelman

Ilana Zigelman (thezigette@gmail.com)

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Abstract

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (1978) which states that learning is social is the basis of constructivism. Students learn through collaboration which is easily accomplished in distance education with advances in educational technology. The Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, 2007) outlines three presences; social, cognitive, and teacher. This framework has been critiqued and further research is necessary. Trello (n.d) is a user-friendly collaboration tool for higher education that supports the constructivist learning theory, which allows students to be self-directed and take ownership of their learning. The notice board layout is clear, concise and accessible to all group members. It is just one of many education technology tools for collaboration available for group tasks in distance learning and is an excellent example of a tool conducive to the constructivist framework.

Keywords: Community of Inquiry, Constructivism, Collaboration, Curriculum, Trello

Introduction

Constructivism “encourages the construction of a social context in which collaboration creates a sense of community, and that teachers and students are active participants in the learning process” (Tam, 2000, p.51). Students learn through interacting with peers and sharing their knowledge. Social Constructivism is a variety of cognitive constructivism that emphasizes the collaborative nature of much learning. Social Constructivism was developed by post-revolutionary Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotzky. His work has become the foundation of much research and theory in cognitive development over the past several decades. Vygotsky argued that all cognitive functions originate in, and must therefore be explained as products of social interactions and that learning was not simply the assimilation and accommodation of new knowledge by learners; it was the process by which learners were integrated into a knowledge community. According to Vygotsky (1978, p. 57):

Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice; first, on the social level and later on, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological). This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals.

According to Vygotsky, language and culture play essential roles both in human intellectual development and in how humans perceive the world. Vygotsky believed that social learning through interaction precedes development; consciousness and cognition is the end product of socialization and social behaviour (Vygotsky, 1978). Social constructivism focuses on how people achieve their goals/purposes within the development or the process of certain technological devices (Winner, 1993).

Background Information

Role of the Teacher

According to Copley (1992), “constructivism requires a teacher who acts as a facilitator ‘whose main function is to help students become active participants in their learning and make meaningful connections between prior knowledge, new knowledge, and the processes involved in learning’” (Tam, 2000, p.52). It is the teacher’s role to guide the students, question them, and facilitate discussions, and create collaborative opportunities for the students to be able to learn from each other. According to Garrison (2007) teacher presence plays a large role in the success of online learning based on student satisfaction, perceived learning, and sense of community. Teachers must create well designed tasks in order to see evidence of the community of inquiry.

Brooks & Brooks (1993) believe a constructivist teacher should be able to: encourage students to take initiative, questions students’ understanding of concepts before providing their own, encourage discussions with peers and with the teacher, encourage inquiry by asking open-ended questions, challenge the students, and assess their understanding. The ultimate responsibility for the teacher is to provide the students with a collaborative environment, opportunities to solve problems where students construct their own knowledge, while acting as a facilitator.

Another important element to consider in distance education is transactional distance. Moore’s (1973) theory of transactional distance “defines distance as a psychological and communications gap that is a function of the interplay among structure, dialogue, and autonomy” (Stein, Wanstreet, Calvin, Overtoom & Wheaton, 2005, p. 106). The role of the teacher is to lessen this distance so the students feel a deeper connection to their peers and to their instructor, and this will enhance the learning process as a result of a greater connection.

Community of Inquiry

The community of inquiry framework revolves around three presences; social, cognitive, and teaching. “The community of inquiry framework (CoI) focuses on the intentional development of an online learning community with an emphasis on the processes of instructional conversations that are likely to lead to epistemic engagement” (Shea & Bidjerano, 2009, p. 544). The COI is meant to develop an online learning group which will have engaging discussions where learning will be constructed. According to Arbaugh, Cleveland-Innes, Garrison & Ice (2008) the community of Inquiry promotes a constructivist-collaborative approach to online learning. Through collaboration, students will learn from their peers and build further knowledge.

Social presence is defined as “the ability of participants in the Community of Inquiry to project their personal characteristics into the community, thereby presenting themselves to the other participants as real people” (Garrison, Andrews & Archer, 1999, p.89). It is necessary to build connections and trust in an online community. It helps build a community of learners and it fosters sharing and collaboration through discourse, but it does not create cognitive presence.

Cognitive presence is defined as “the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse in a critical community of inquiry” (Aykol & Garrison, 2009, p.235). It is vital for critical thinking, which is the ultimate skill in higher education. Garrison’s model divides cognitive presence into the four phases of the practical inquiry model; triggering event, exploration, integration and resolution. The triggering event starts the inquiry process through an activity to promote full participation from the students. The exploration phase focuses on the actual problem and searching for information and an explanation. The integration phase is more focused and structured on constructing meaning. The resolution phase resolves the problem by finding a specific solution or by constructing a framework (Akyol & Garrison, 2009).

Teaching presence is defined as “the design, facilitation and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes” (Garrison, Cleaveland-Innes & Fung, 2009, p.32). It is necessary for satisfaction and success in an educational community of inquiry. According to Garrison (2009) higher level thinking occurs when a community of learners are engaged in discussions and reflections. It is the teacher’s responsibility to design learning activities and the presentation of course content, as well as facilitating the discussion and supporting the social and cognitive presence. A study conducted by Shea and Bidjerano (2009) surveyed 2000 online learners and found that teaching presence established and maintained cognitive and social presence.

Critiques

According to Annand (2011) social presence is of questionable value in the online higher education learning experience because its effect on cognitive presence is unproven. Rourke & Kanuka (2009) argued that the most important element in an online learning experience is for it to result in deep and meaningful learning, which they found did not occur but rather students only achieved surface learning through completion of assignments.

Aykol et al. (2009) responded by stating that the COI framework was based on the constructivist model and not “outcomes based” and therefore deep and meaningful learning is not a variable in reporting on the teaching and learning process. Rourke & Kanka (2009) believe that the influence social presence in online learning is overstated. Shea and Bidjerano (2009b) argued that asynchronous group communication is not sufficient for a COI. Shea et al. (2010) conducted a study of 1000 online interactions between 2 identical courses taught by different instructors. The purpose was to measure the extent of the three presences.

…several specific indicators of social presence are very difficult to interpret reliably. All of these issues indicate that the social presence construct is somewhat problematic and requires further articulation and clarification if it is to be of use to future researchers seeking to inform our understanding of online teaching and learning. (Shea et al., 2010, p. 17)

Their findings indicated a possible lack of correlation between learning and social presence. Annand (2011) strongly believes that the CoI framework’s concept of online learning as a process supported by collaborative, constructivist activity requiring two-way communication is questionable. More research is necessary.

Applications

Constructivism from a Curriculum Perspective

“Students have greater opportunities with electronic collaboration tools to solicit and share knowledge while developing common ground or intersubjectivity with their peers and teachers” (Hara, Bonk & Angeli, 2000, p.140). There are many choices of online collaboration tools which are necessary in distance education, as peers are generally from different places. According to Brooks & Brooks (1993) constructivists ask learners to solve meaningful and realistic problems which help students to take ownership of their learning, which is conducive to Inquiry or Problem based learning. There are two prevalent characteristics which seem to be central to constructivist descriptions of the learning process: Good Problems and Collaboration. Good problems stimulate exploration and reflection necessary to construct knowledge. Characteristics of a good problem require making and testing a prediction, solvable using inexpensive equipment, realistically complex, benefits from a group effort, and must be seen as relevant and interesting by students. The constructivist perspective believes learners learn best through interaction with others and collaborating to find a solution to the problem. The conversations that occur through this process allow students to refine their knowledge.

Problem Based Learning and the Role of Technology

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an instructional model where students learn through solving problems while the teacher facilitates and guides. “PBL is well suited to helping students become active learners because it situates learning in real-world problems and makes students responsible for their learning” (Hmelo-Silver, 2004, p. 236). Students take ownership by working together towards a shared goal to solve problems which are relevant and authentic. PBL fully supports the constructivist framework as the purpose is to collaborate with peers and learn from each other. This is much easier to accomplish with so many technology tools to support the collaborative process.

Technology has made information accessible from any part of the globe and brought a mode of collaboration which promotes a sense of community through education. According to Brown-Pobee & Adomza (2016) technology is allowing for the students learning to be autonomous and allow for self regulated learning.

Trello

Trello (n.d) is a web-based collaboration and project management tool that organizes your projects into boards. It lets you know what is being worked on and by whom. It is an excellent tool for academics as it is great for managing projects. Trello is best used for Secondary and Post secondary education as it is rather advanced for the elementary panel. Trello can be used on various devices and has a very simplistic interface that makes it user friendly. It has 3 versions; free, business-class, and enterprise.

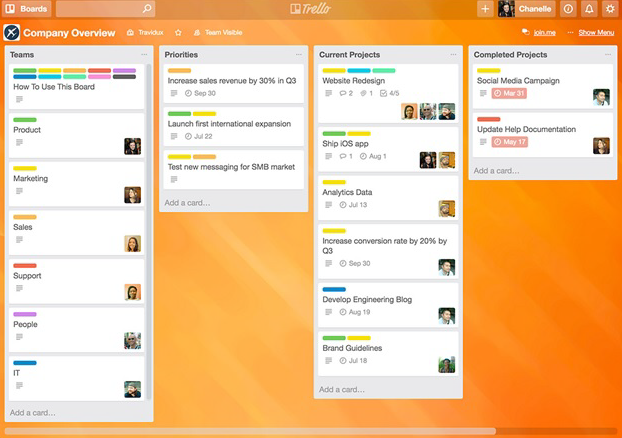

Kaur (2018) reviewed the app and acknowledged that the business-class and enterprise versions had more features, however focussed on the free version for the review. Trello is based on the Kanban system, which in Japanese means ‘card’ or ‘sign’ and is the name used to describe an inventory control card (Arbulu, Ballard & Harper, 2003). It is organized as a notice board where one can post notes, such as to-do lists or timelines. It can be used for brainstorming and organizing collaborative projects. These can be updated and managed as the projects progress. Figure 1 is a sample of a collaboration board taken directly from www.trello.com. It clearly shows what needs to be done and the progress of each element. Every item in the list is referred to as ‘a card’.

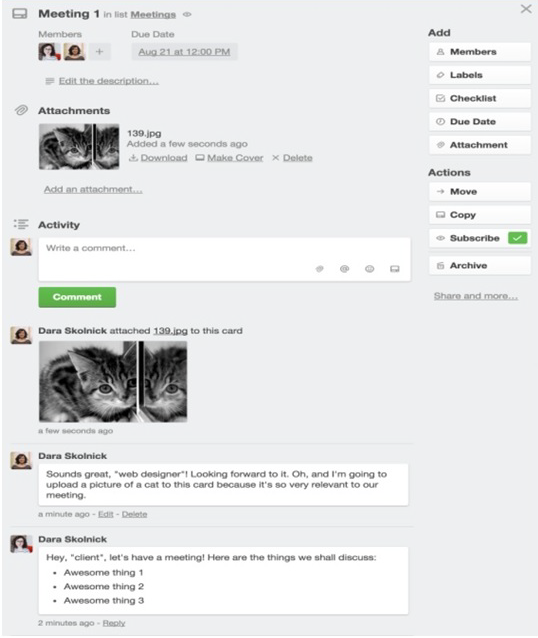

Due dates, checklists, images, links and YouTube videos can be added to the comments section within the cards. Everyone has control over organization which is another element of Trello’s flexibility. It should be discussed within the group how it will be updated and how often.

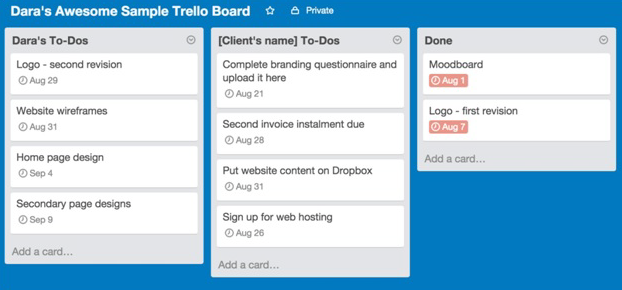

Figure 2 is a sample client board that is clearly organized. It shows the to-do list with due dates and keeps track of completed tasks.

Figure 3 shows what occurs when you click on an item in the list, otherwise known as ‘a card’, which will show details such as due dates, file uploads and messages.

Motivation is tied to self efficacy; believing one can accomplish a task. Trello allows for students to set goals and check them off once completed (Ray, 2016). Trello “encourage adaptable attitudes of those working in higher education towards new methods and techniques of organization and planning” (Prtljaga, Nedimovic & Đordev, 2015, p.303). Trello will simplify the collaboration process while keeping individuals accountable and recording progress.

Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Distance education is continuing to gain popularity due to its flexibility. Through continuing advances in technology, students are finding it to be a more viable option. The Community of Inquiry framework has demonstrated that teacher, social and cognitive presence are strong in online learning and fully support constructivism, and this reduces transactional distance. Collaboration tools make it easy for PBL and Inquiry models to be implemented successfully. Future research should explore new technologies that will further support constructivism and the Community of Inquiry.

References

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12, 3-22.

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2009). Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: Assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning_1029 233… 250. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(2), 233-250.

Annand, D. (2011). Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(5), 40-56.

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., & Ice, P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the Community of Inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. Internet and Higher Education, 11, 133-136.

Arbulu, R., Ballard, G., & Harper, N. (2003). Kanban in construction. Proceedings of IGLC-11, Virginia Tech, Blacksburgh, Virginia, USA, 16-17.

Brooks, J. G. and Brooks, M. G. (1993). In search of understanding: the case for constructivist classrooms, Alexandria, VA: American Society for Curriculum Development.

Brown-Pobee, J. P. Y., & Adomza, G. K. (2016). Digital Tools to Improve International Collaboration and Distant Education.

Garrison, D. R. (2003). Cognitive presence for effective asynchronous online learning: The role of reflective inquiry, self-direction and metacognition. Elements of quality online education: Practice and direction, 4(1), 47-58.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105. Doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 5-9.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating Cognitive Presence in Online Learning: Interaction Is Not Enough. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133-148.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. The internet and higher education, 13(1-2), 31-36.

Hara, N., Bonk, C. and Angeli, C. 2000. Content analyses of on-line discussion in an applied educational psychology course. Instructional Science, 28(2): 115–152

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn?Educational psychology review, 16(3), 235-266.

How to use Trello for project management with your clients. (2016, January 27). Retrieved June 5, 2018, from https://daraskolnick.com/using-trello-for-awesome-client-facing-project-management/

Jonassen, D., Davidson, M., Collins, M., Campbell, J., & Haag, B. B. (1995). Constructivism and computer‐mediated communication in distance education. American journal of distance education, 9(2), 7-26.

Kaur, A. (2018). App review: Trello. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 18(1), 95. doi:10.1080/15323269.2018.1400840

Prtliaga, P., Nedimovic, T., & Đordev, I. (2015). Improving Organization and skills of planning in Higher Education Using New Informational Communicative Technology, under the auspices of the President of the Republic of Croatia, 303-312.

Ray, N. (2016). Prioritize, Plan, and Maintain Motivation with Trello. The Agricultural Education Magazine, 88(6), 16.

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2009). Community of inquiry as a theoretical framework to foster ‘‘epistemic engagement” and ‘‘cognitive presence” in online education. Computers & Education, 52, 543-553.

Shea, P., Hayes, S., Vickers, J., Gozza-Cohen, M., Uzuner, S., Mehta, R., Valchova, A., & Rangan, P. (2010). A re-examination of the community of inquiry framework: Social network and content analysis. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1– 2), 10–21.

Stein, D. S., Wanstreet, C. E., Calvin, J., Overtoom, C., & Wheaton, J. E. (2005). Bridging the transactional distance gap in online learning environments. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19(2), 105-118.

Tam, M. (2000). Constructivism, instructional design, and technology: Implications for transforming distance learning. Educational Technology & Society, 3(2), 50-60.

Trello. (n.d.). Retrieved June 5, 2018, from https://trello.com/

Vygotsky, Lev (1978). Mind in Society. London: Harvard University Press.

Winner, L. (1993). Upon opening the black box and finding it empty: Social constructivism and the philosophy of technology. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 18(3), 362-378.