Technology Integration Models and Barriers

8

Nair Lacruz

Nair Lacruz (nairlacruz@yahoo.ca)

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Abstract

As technology integration in the classroom is becoming increasingly popular, it becomes increasingly important to have models or frameworks for educators to use to reflect on that integration. The SAMR model has four levels of integration (substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition) that provides a framework or template for educators to gauge their integration levels. The SAMR model is a useful tool to reflect on classroom and institutional technological integration.

Keywords: education, SAMR, technology.

Introduction

Integrating technology into curriculum can be a difficult task, as it requires the educator to align content and technology in a way that allows outcomes to be achieved in a meaningful way for students. As students are becoming more technology savvy, it is requiring educators to keep up with technological advancements and to have the skillset to integrate them into the classroom. According to Tapscott (2009), this ‘Net Generation’ expects and even demands innovation in all areas of their life and education will be no exception. For educators to evaluate their level of integration into the classroom they will need tools to do so as the number of technologies is not the measure that it is needed but the quality of integration that needs to be measured. The SAMR model is a tool that can be used by educators to measure not just the number of technologies being used but also at what level of integration they are being used at in the classroom activities.

Background Information

The section will provide an overview of the SAMR, created by Puentedura (Puentedura, 2003), some criticisms and potential uses for the SAMR model.

Model Overview

The SAMR model was created to help in planning and assessing the levels of technologies used in the classroom (Jacobs-Israel, & Moorefield-Lang, 2013). This model looks to aid teachers, administrators, and educators in examining the use of technology in the classroom (Jacobs-Isreal et al., 2013). Although technology in and of itself cannot be the only guiding principle for curriculum development the SAMR model allows the educator to evaluate the level at which the students are using technology and “…becoming creators of their own knowledge” (Green, 2014, p.18). The model is encouraging that curriculum be created in a way that allows students to also learn the technological skills needed in the 21st century (Hilton, 2016).

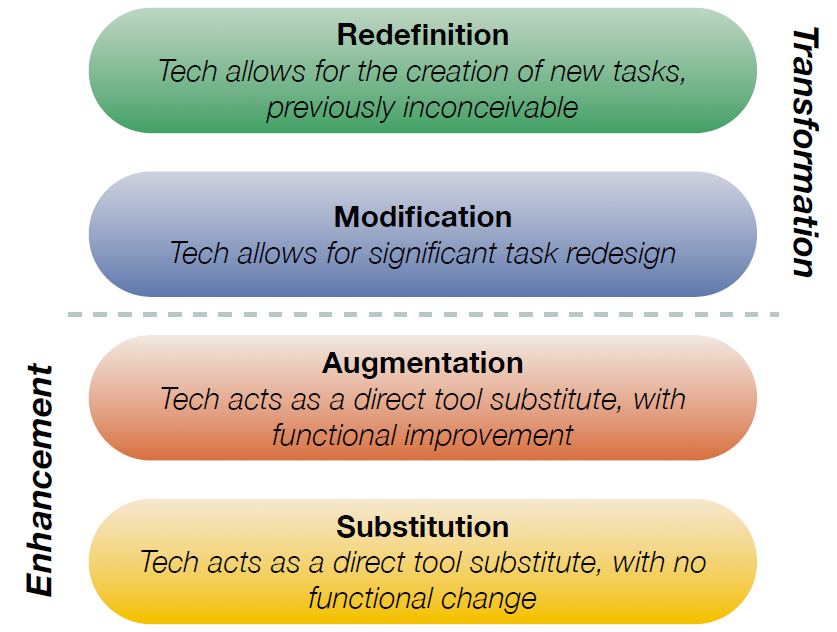

The SAMR model is a tool for “…assessing and evaluating technology practices and impacts in the classroom setting” and can be examined at both the student and teachers levels (Kihoza, Zlotnikova, Bada, & Kalegele, 2016, p.108). The hierarchical model is clear and simple to use, allowing the educator to interpret the levels. SAMR is an acronym for substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition. The levels substitution and augmentation are further defined as the category of enhancement, while modification and redefinition are further defined as the category of Transformation. Figure 1.0 shows the SAMR model as a hierarchical model that starts at substitution and ends at redefinition.

The enhancement category refers to the technological adoptions that does little to no changes to the task (Hilton, 2016). At the substitution level, the technology is replaced with one level of technology for another (Puentedura, 2013). A common example of this is to provide lecture notes online instead of photocopies, as there is no change to the content this is considered to be at the substitutional level. In the augmentation level, the technology replaces, with slight enhancements, the previous technology. Some examples of augmentation are to have first graders read and listen to digital stories individually rather than be read to as a class by the teacher (Hamilton, Rosenberg, & Akcaoglu, 2016, p. 434). Another example of augmentation is evident in a study that uses text messages to aid in nursing students learning medical information. One group of students were sent text messages twice a day containing specific medicines, while the other group did not. The study found that those who received the review text messages had retained more of the information than those who did not receive the text messages (Romrell et al., 2014).

The transformation category is when the learning activity is modified substantially due to the integration of the technology (Hilton, 2016). At the modification level, significant changes to the educational task are required. An example to illustrate is when a flood disaster simulator was redesigned for an applied geomorphology course. The simulated questions were adapted to use in text messages that the students would receive. The sequence of text messages depended on how each student responded to the text messages. This redesign allowed for an individual experience for each student via his or her mobile devices (Romrell et al., 2014). The redefinition stage is the highest level of the SAMR model and, therefore, the highest level of the transformation level. The redefinition stage is when technology is used to create a new educational task that would not be possible without technology (Hamilton). An example of the redefinition stage occurred in a research study that had two control groups in an architecture studies class. One group of students used augmented reality (AR) to view architecture plans on site (redefinition stage) while the control group used the current 2D and 3D methods. The study found that the students in the AR group outperformed those in the non-AR group (Romrell et al., 2014). Although the SAMR model is quite useful tool for the implementation of technology in curriculum, it is not without its criticisms.

Criticisms

Although SAMR is a popular model (Green, 2014) it is not without its criticisms. The first criticism is in regards to the creator of the model Dr. Ruben Puentedura. Although Puentedura has a 12-year teaching history at Harvard University and Bennington College it seems that his SAMR model is based on his personal experience and not on academic research (Green, 2014). Since Green’s article, some peer-reviewed articles have been written but none by Puntedura. According to Green (2014) there is no known academic research study or academic paper by Puentedura on the topic. Shortly after creating the model Puendetura left academia and started his own consulting firm (Green, 2014). The consulting firm Hippasus offers many educational training services and resources including many of Puentedura’s conference presentation slides as recent as May 2018.

The criticism extends past that of the inception of the model but to the model itself. Hamilton et al. (2016) argue that the model has three challenges: absence of context, rigid structure, and product over process. According to Hamilton et al., context is needed when examining technology in the classroom and this model does not allow for this context to be examined. Understanding context such as the social economics of the school/community, the teacher’s technological knowledge, administrative support etc. play a direct impact on the integration, or lack thereof, of technology in the classroom. The hierarchical structure of SAMR is argued by Hamilton et al. (2016) to be too rigid as the hierarchal structure of SAMR does not always reflect higher levels of learning/outcomes and this leads to their third criticism that technology improvement should not be the first focus of designing curricula. The main focus should be that of student outcomes and the SAMR model focuses entirely on technological adoption and not the learning outcome(s).

SAMR Model Potential

Despite some of its criticism, the SAMR model has potential uses. The critics of the model are correct that learning outcomes are the ultimate measurement; however, educators have many resources and academic theories to help create and evaluate curricula. The educational landscape is changing and technology is becoming part of the curricula and it is argued that it is required to learn, as technological literacy is quickly becoming a required 21st-century skill (Hilton, 2016). As such, educators need a model or framework to aid in their assessment of their level of technological integration in their classroom. Critics such as Green (2014) even acknowledge that the model is simple to use and that it can be “…easily adapted and interpreted in multiple ways. It implies a hierarchy behind tech tool use, giving us a “goal” to shoot for that is quickly explained to an administrator or to a grant evaluator.” (p.38). Hilton (2016) argues that the SAMR model is a useful reflective tool for educators to use to understand the use of the technology in reaching the particular outcomes rather than using it as a tool to use in designing curricula. Understanding the SAMR model cannot be used in isolation of pedagogical theory. The SAMR can be used as a model to assess the level of technological integration that is now a required 21st Century Skill.

Applications

The SAMR model can be utilized to reflect and assess on the integration of technology in education. There are two areas where the SAMR model can be utilized as a reflective exercise: at the classroom level or at the institutional level.

Reflective on a Classroom Level

Reflecting on your classroom experiences as an educator is a key element in improving student outcomes. The SAMR model is a tool that can be used to assess the integration of student’s use of technology in reaching the course/activity outcomes.

Hilton’s (2016) research was to have social sciences teachers reflect on their teaching and to codify their activities using the SAMR model. Hilton found that instead of the activities gradually going up the SAMR model throughout the year that they varied depending on the activity. Teachers reflected that there was a difference between technology for “…content acquisition…” and using technology for the “…practice of key social studies skills.” (Hilton, 2016, p. 71). Teachers realised that technology used for content acquisition fell into the substitution and augmentation levels of the SAMR model and the practice of social studies skills fell into modification or redefinition levels. During the reflective process of using the SAMR model, teachers recognized activities that could be changed to have the activity be at the modification or redefinition levels of the SAMR model (Hilton, 2016). According to Hilton (2016), the SAMR model allowed activities to be examined to reflect on the opportunity for technology to be embedded.

The SAMR model can also be used as a tool to reflect on if a specific technological modality is useful in the classroom. Romrell et al. (2014) argue that the SAMR model can be used as a template to categorize and evaluate mobile device use in learning (mLearning). For the substitution level examples of mLearning opportunities were examined, such as podcast lectures, using cellphone video cameras and using mobile devices for asynchronous online discussions. The results indicated that the students enjoyed using the mobile devices and that it allowed them to engage in the learning outside of traditional school hours and location. At the augmentation level, research was done comparing a marine biology course where one group used a printed field guide with species information and a second group used a portable DVD player that used video and audio to display the same species information. The research shows that the group using the portable DVD demonstrated higher learning in a post-test (Romrell et al., 2014). In the transformation category, mLearning can be used to enhance the students learning. In the modification and redefinition levels using mobile apps in education can create opportunities for group meetings, video, and presentations. One area of great interest is that of augmented and virtual reality. One example is that in new language acquisition. One research developed an augmented reality mobile app that used GPS and the location device on a cellphone. Using the student’s location the app would display English descriptions of the items in the area over the image in the student’s camera phone. Students were more engaged in their learning and the authors concluded that it may have increased the student’s language acquisition (Romrell et al., 2014).

The use of the SAMR model can be beneficial to reflect on an educator’s classroom to review where technology can be embedded and at what level of integration. In addition, the model can be used as a tool to reflect on a specific technological modality, such as mLearning, and use the model as a template to categorize and evaluate the effectiveness of the learning. These categorized and evaluated modalities can inform your classroom technology-enhanced activities.

Reflective on an Institutional Level

The SAMR model is an effective model for teachers or researchers to reflect on their specific classroom or research. However, the model also can be used to the gauge the technological activities, or lack thereof, at an institution. It is difficult for an institution to know the level of technological integration in the classrooms and the SAMR model can aid in getting a high-level understanding of adoption levels. In this particular case, an institution can refer to a cluster of classes, an entire school, or even multiple schools.

Institutions can create surveys using the SAMR model to ask educators to self-identify what technologies they use in the classroom and what technologies they require students to use in their activities (Kihoza et al., 2016). Once compiled together this would give administrators a sense of what is occurring at the institution and the teachers’ knowledge and willingness to use technology. Kihoza et al. (2016), research focused on teacher trainees in Tanzania where their findings indicate a low level of technology use and understanding of how to integrate it into the curriculum with only 25.6% of teacher trainees reported being well prepared and 39.1 % reported being poorly prepared to integrate technology into the classroom (Kihoza et al., 2016). Although many teacher trainees reported using technology in the classroom with 38.5% reporting sometimes and 28.2% reporting often, 50% of teacher trainees demonstrated that they were unprepared for classroom technology integration (Kihoza et al., 2016).

Another way that an institution can utilize the SAMR model to gauge technology adoption in their classroom is to investigate what technologies are being utilized by the educators in the classroom and what technologies those educators are asking the students to use as well. Jude et al., conducted research to understand the adoption of ICT at Makerere University. The study looked at the levels of the SAMR model to see what was occurring at each of these levels. The most common technological uses for substitution and augmentation were using an ICT for lectures, notes, assignment creation at 74.7%, the use of PowerPoint with 48.5%, and the use of a search engine with 77% stating as always. The least common was 86.4% never recorded lecture material and 95% never having used Skype to teach. (Lubega, Kajura, & Birevu, 2014, p. 110-111). This research found at the levels of modification and redefinition was that 83% never used electronic games while 78% never use MOOCs. (p.113). What the researchers were most surprised to find is the comparisons at the college/department level. The researchers discovered that the department that was to lead the ICT integration at the University had the second highest levels of never having using an internet search engine at 6.1% (p. 111). Using the SAMR model to create and codify the questionnaire the researchers were able to get a University level analysis of how technology was or was not being integrated into the classroom and curricula.

Although these research studies results are specific to their unique situation they illustrate the ability to apply the SAMR model beyond an individual classroom. Using this model research can be done to illustrate the level of technological integration that is occurring within an institution. The results of that research can assist in allocating resources to support the further integration of technology into the classroom.

Conclusions and Future Recommendations

The SAMR model is a popular model to categorize learning activities within the levels of technological integration of substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition. The model is a useful tool to reflect on an educators’ integration of technology within their own classroom but can also be used by institutions to gauge the level of integration across the institution. More research is needed on the model itself as well as more research is needed on the application of the model. This research can focus on when the model can and cannot be used and if any other theoretical frameworks need to be applied alongside of the application of the SAMR model.

References

Green, L.S. (2014). Through the looking glass: Examining technology integration in school librarianship. Knowledge Quest, 43(1), 36-43. Retrieved from http://link.galegroup.com.uproxy.library.dc-uoit.ca/apps/doc/A

Hamilton, E. R., Rosenberg, J. M., & Akcaoglu, M. (2016). The substitution augmentation modification redefinition (SAMR) model: A critical review and suggestions for its use. TechTrends, 60(5), 433-441. doi: 10.1007/s11528-016-0091-

Hilton, J. T. (2016). A case study of the application of SAMR and TPACK for reflection on technology integration into two social studies classrooms. Social Studies, 107(2), 68-73. doi:10.1080/00377996.2015.1124376

Jacobs-Israel, M., & Moorefield-Lang, H. (2013). Redefining technology in libraries and schools: AASL best apps, best websites, and the SAMR model. Teacher Librarian, 41(2), 16-18. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.uproxy.library.dc-uoit.ca/docview/1470785965?accountid=14694

Kihoza, P., Zlotnikova, I., Bada, J., & Kalegele, K. (2016). Classroom ICT integration in Tanzania: Opportunities and challenges from the perspectives of TPACK and SAMR models. International Journal of Education & Development Using Information & Communication Technology, 12(1), 107-128.

Lubega T.J., Kajura M.A, & Birevu, M.P. (2014). Adoption of the SAMR model to asses ICT pedagogical adoption: A case of Makerere University. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 4(2) 106-115. doi: 10.7763/IJEEEE.2014.V4.312

Puentedura, R. (2003). An Introduction. [Web page]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/000001.html

Romrell, D., Kidder, L.C, Wood, E. (2014 ). The SAMR model as a framework for evaluating mLearning.

Online Learning, 18(2), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v18i2.435

Tapscott, D. (2009). The eight net gen norms. In Grown up digital (pp.75-96). Toronto, Ontario: McGraw-Hill.