Andreu Arinyo i Prats

Andreu Arinyo i Prats

IFISC-CSIC

Abstract

The loss of cultural complexity and diversity is a common phenomenon throughout human and potentially non-human history, often in relation to major external shocks. Yet, there are few studies that analyse cultural loss as a topic of research. Difficult questions like the study of cultural resilience need to be answered by the use of a diverse set of tools and datasets that goes beyond the level of multidisciplinarity that currently exists on the cultural studies fields, what is needed is deep conversations and collaboration of multiple research fields and non-academic actors, providing statistical methods, data extraction and analysis, as well as a global understanding of the topic. CLUB-DECES homes in on the resilience of culture under demographic, climatic and environmental shocks –the occurrence of which is prognosed to become more frequent and severe in the future. By modelling and analysing drastic changes in population or in the environment brought about by shocks CLUB-DECES pursues to measure the cultural resilience of culture by adapting methodologies based on Bayesian inference commonly used in cosmological studies. Thus CLUB-DECES involves multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary studies, combining numerical and analytical modelling from a wide suite of fields, primarily using tools developed to model cosmological datasets, data science, archaeological and anthropological data extraction, together with the most susceptible communities, their representatives and involved the institutions. This ambitious endeavour shall study culture in the human and non-human realm, aiming –on the basis of past datasets– to forecast the requirements to achieve a general measure of the shock-induced tipping-points of culture. This is highly relevant now at a global and European scale. Globally climate change and environmental degradation bring to the tipping-point many vulnerable societies, human and non-human. In Europe, rural areas and whole member states, like Bulgaria, are losing large amounts of population due to migration. CLUB-DECES results will shed new light on our understanding of the past, and thanks to that help our present and have influence on the preservation of cultural diversity for future generations.

Keywords: Transdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, cultural loss, resilience, shocks, disasters, Bayesian statistics, policy-making, data-sets, agent modeling, mock data.

1. Transdisciplinarity

In research, especially in research concerning the human and cultural domain, there are many questions that due to their complexity need a multidisciplinary approach involving a wide diversity of academic areas. However, for cultural studies, this academic multidisciplinary research is not enough and it has to go beyond working with tools and methods from multiple fields. The study must also involve, to the degree that is possible, the communities that are the focus of the study, the policymakers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other organisms that represent and interact with them. This global framework will be referred to as transdisciplinarity through this text.

The work that is presented here: Cultural Loss Under Bottlenecks – DEmographic, Climatic and Environmental Socks (CLUB-DECES), is especially relevant in the advancement towards a transdisciplinary framework because its main goal is to establish cultural loss as an area of research, by involving not only many different academic fields, but also –by necessity– include the non-academic actors that have a saying on cultural resilience. The communication between all the spheres is essential in CLUB-DECESS because to be able to measure resilience one has to properly interpret the data in order to make extensive use of numerical methods. These conversations and methods are indispensable to estimate the cultural loss tipping-points triggered by demographic, climatic and environmental shock events among different past and present societies, as well as non-human animal cultures.

Cultural loss is a highly relevant topic for all humankind, as it is a common phenomenon that repeatedly occurs throughout history, to the degree that it is even in present in the collective conscience, exemplified by awareness of the disappearance of the Iberians as a distinct culture, the fall of the Roman Empire, or no longer using horses as the main means of transport and its repercussions, to name but a few. However, it is difficult to differentiate between a normal loss of culture brought about by cultural evolution, where cultures change gradually through time, as opposed to a loss of culture that results in the sudden disappearance of unique knowledge, producing a decrease of local and global diversity of culture.

In order to disentangle these two phenomena and focus only on the sudden loss of culture, it is necessary to study societies that have been hit by a sudden abrupt disaster, or shock. In them then measure which are the repercussions on the survival of the cultural expressions that were present into the community (Companion, 2015). This focus on shocks allows marginalizing over complex dynamics that drive cultural evolution in its many forms, enabling to capture the mechanisms that operate over cultural resilience and avoiding many of the more complex issues of cultural evolution. Moreover, this approach puts forward the need to study cultural systems against disasters and shocks, as shocks are a common occurrence in nature and, at present, there are no works that study numerically the effect that these have in cultural survival. This work strongly arises the need for transdisciplinarity, to involve the communities and actors that can identify and understand the susceptibility of cultural traditions against shocks.

This involvement has to contribute to have a more integrated development on each of the phases of the research in cultural loss, where an ad hoc methodology has to be developed to tackle this complex topic: a common vocabulary has to be created; which data will be the most relevant and why; this data then has to be interpreted, transformed in numerical values, be processed mathematically; and then the results be translated into meaningful units to be shared with the community. For each of the processes in the way, there must exist a profound conversation and understanding between the experts of each of the disciplines involved, as well as to involve those social sectors that will be affected. This shall allow them to have a crucial input in the key steps of the analysis, in order to produce a relevant practical output that should help conscience about cultural loss and provide further tools to increase resilience.

Moreover, it has to be noticed that this transdisciplinarity goes beyond current multidisciplinary research being done in cultural evolution, which tangentially deals with the loss of culture. Cultural evolution, by necessity, is already a highly multidisciplinary field involving research from archaeology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, paleoclimatology, complex systems and physics, among others (Mesoudi, 2016). However, as much as that field already works with a wide range of datasets and numerical modeling, it has not yet attempted to compute cultural resilience against abrupt shocks and disasters, nor has it delved into conversations with current stressed communities most susceptible to cultural loss.

2. Relevance of Resilience

CLUB-DECES focuses on cultural resilience or cultural heritage resilience –the capacity to preserve cultural traits long established in a community. This is currently a highly relevant topic in a world so exposed to shocks and abrupt change. The loss of traditional knowledge is already identified as a consequence of environmental change and degradation by The United Nations Environment Programme Convention on Biological Diversity, Article 8(j) (INTER-SESSIONAL, 2005). Moreover, in the last decades the UNESCO established the Intangible Cultural Heritage lists which recognizes the significance of non material cultural heritage as “a repository of cultural diversity and of creative expression” and the need to safeguard it (UNESCO, 2003).

Yet, targeted research has so far been very limited, especially there is a worrying lack of modelling of the processes that drive cultural loss in order to understand their underlying casualties. It is especially relevant at the present because we inhabit a rapidly changing world involving social, cultural, technological and environmental disruptions, climate change, mass migrations, and habitat degradation. At a global scale, climate change and environmental degradation is prognoced to be much more severe, and this will likely bring to the tipping-point of cultural loss for many susceptible societies. These are already producing an age of extinction, not only on the biological front but also in the cultural sphere, leaving an immense imprint on cultural preservation (Dryzek et al., 2011), especially in traditional knowledge and even in non-human animal cultures (Brakes et al., 2019).

Exploring this avenue of biological and cultural comparison, recently it has been observed that the global diversity of species is decreasing fast, despite the remaining ecosystems having similar numbers of species. This is because more generalist species take the ecological space that was occupied by local ones that get extinct or retrocede to smaller habitat range (Dornelas et al., 2018). By focusing on cultural loss, a similar assessment of this loss of culture at local and global level can be attempted. This would enable to produce a preliminary picture of similar trends that cultural diversity is experiencing when exposed to shocks in a globalized world.

Moreover, such an approach can contribute to thinking in terms of cultural ecosystems, that is, understanding the macro-evolutionary dynamics accounting for socio-ecological networks at different scales. These dynamics involve many cultural traits and social interactions that are key to maintain a rich and resilient ecosystem, which can better withstand shocks. Furthermore, by studying the resilience of different cultures and cultural traits, allows assigning a risk of disappearance that they experience, similar to the list of the most endangered species.

3. Instances of Cultural Loss Under Bottlenecks Induced by Shocks

From an academic point of view it is important to incorporate shocks because, even though the field of cultural evolution has seen a range of studies linking demography and culture, generating a vivid debate (Henrich, 2004; Shennan, 2001; Collard et al., 2016; Aoki, 2018), such studies tend to focus only on evolution over long time scales. They have so far neglected for the most part the study of the impact of short-term shocks on culture, with only a few exceptions (Rorabaugh, 2014; Premo & Kuhn, 2010; Fogarty et al., 2017). These, nevertheless, study the effect of the shocks many generations after and ignore the short-term impact. By studying the effect of shocks these would better describe pressures on the cultural evolution of the system, helping to disentangle the debate of demography and culture, plus the ability to describe historical and modern events of shock-induced loss and survival.

When dealing with cultural loss in short-term shock events and susceptible to be studied, the scope of cases is illustrated by a broad range of instances where communities have experienced or might experience them:

- Epidemic and plagues. For example, it was recorded that an Inuit community hit by a plague lost some technology when key members of the community died (Boyd et al., 2011). It also might affect current cultural practices, one can not help but wonder if cultural traits like kissing as a greeting gesture will not be extinguished in some parts by a health emergency like the current COVID-19 pandemic.

- Environmental degradation. It can be observed that in many communities of all socio-economical backgrounds cultural preservation is affected when the community is displaced or affected by a shift in their environment in the form of storms, volcanic eruptions (Riede, 2014), displacement and droughts (Companion, 2015). For example, it has been observed that the displacement after the Fukushima nuclear disaster and tsunami is threatening the cultural survival of its traditional residents.

- Persecution and cultural imposition of cultural characteristics, such as Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge, where traditional cultural expressions were prosecuted (De Walque, 2004). El Salvador during its dictatorship where they efficiently rooted out the use of indigenous languages because they were associated with ideology (Lemus, 2004), or China during the Cultural Revolution where traits such as traditional theatre and music were systematically eliminated (Mackerras, 1973).

- Rural exodus into the cities, resulting in an attendant loss of local knowledge, both in developed and developing societies, as is the case of many European rural areas, resulting in an attendant failure to keep of local knowledge, both in developed and developing societies, as is the case of many European rural areas such as Spain’s interior (Polo et al., 2009) and Italian alps (Ianni et al., 2015) where local botanical and environmental knowledge is being lost.

- Low natural growth and migration. This is the case in Europe for many ex-communist countries (e.g. Bulgaria, Moldova, and Latvia have experienced more than 20% of population decline in the last 30 years and expect further losses) (Pitheckoff, 2017).

- Acculturation of communities that are being more integrated within neighbouring communities by improved infrastructure, bringing access to resources and means of communication external to them. For example, in a multidecadal study it was observed that communities in the Amazon would lose more ethnobotanical knowledge the closer they were to roads and markets (Reyes-García et al., 2013).

- Non-human animal cultures shall also be considered. For example, just recently it has been observed the proximity of chimpanzee communities to human infrastructure correlates strongly with the lack of richness in cultural traits that can be observed in the communities (Kuhl et al.,2019).

In general, any society or group that is exposed to harsh economic shocks, wars, internal conflict, genocide, epidemics, natural disasters and famine may see the loss of cultural richness and complexity. Such factors were frequent in the past and likely will keep occurring in the present world (Dryzek et al., 2011).

4. Cultural Classification and Use of Cultural Proxies

When talking about cultural loss one can consider knowledge, diversity and culture as a whole, even though culture and knowledge are difficult to distinguish, define and measure in an exhaustive way (Stump et al., 2013; Whyte, 2013; Haidle et al., 2016). For example, the United Nations Environment Programme defines traditional knowledge as:

’[T]raditional knowledge’ refers to the knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities, developed and shared through experience gained over time and adapted to the local social structure, culture and environment. Such Knowledge tends to be collective in nature.

However, other schools of thought defend the concept of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) (McGregor, 2008):

TEK is viewed as the process of participating fully and responsibly in such relationships [between knowledge, people, all of Creation (the natural world as well as the spiritual)], rather than specifically as the knowledge gained from such experiences. … This means that, at its most fundamental level, one cannot ever really acquire or learn TEK without having undergone the experiences originally involved in doing so.

Therefore, different understandings of culture, and even more, the need to consider the practice of a cultural trait as an intangible knowledge, as TEK illustrates, make, impossible to consider the complete cultural content of a society for this study. For simplicity, culture will be defined to mean all the information of a society that can be transmitted through different generations by any learning mechanism (Borgerhoff et al., 2006). It has to be highlighted that this is a practical definition; at this point, it is impossible to consider the complete cultural content of a society for this study.

It is already difficult to classify a cultural trait in a given culture, therefore it is extremely challenging to do so in a way that it can be compared across cultures, but a first attempt will be made to identify proxies for the communities being studied, this is already done in other studies where for example pattern of dots in decoration of ceramics is used as a proxy of cultural traditions (Crema et al., 2016b).

To make the proxies as general as possible, with the help of experts and the communities, cultural traditions could be classified in the temporal, spatial, energetic, and social scales in which the trait is expressed. For temporal scales this means the periodicity of usage, be it daily, weekly, monthly, yearly and so on. For spatial scales this concerns the distances involved in obtaining the required resources for a society, i.e. what is the geographical extension needed to make use of the trait, e.g. resources for tool making. Energetic scales would relate to the energetic cost of the trait to be expressed. Social scales would account for the dimension of the social network needed to put in practice a trait.

Later on, this classification would be carried out for as many and as diverse systems as possible, extracted from sources data-banks such as Seshat (Turchin et al., 2015), Human Resource Area Files (Biesele et al., 2013) and D-PLACE (Kirby et al., 2016), as well as a set of individual works and cases. From these works a meta-analysis has to be conducted to obtain results from the trans-study comparison of all the collected data. Finally, from the experience of the pilot projects and the conversations with experts and communities, guidelines will be created to structure and compile future datasets in a way that the methodology is standardized and the data can be used in a homogenous way across many different studies.

5. Numerical Approach

Research already exists that focuses on cultural survival (Day, 2016) and preservation of cultural heritage in rural communities (Ruritage, 2019). Yet, this research usually focuses on present day issues, usually ignoring historical events that would greatly inform on shock-induced processes that current communities are facing or might experience in the future. Unfortunately, historical events are difficult to fully reconstruct, that is why there is the need for a numerical approach that will reinforce, broaden and validate the perspective that is already being researched. Moreover, numerical analysis has the unique property of being able to conduct a more abstract approach, describing mathematically highly complex aspects of a system. This allows identifying broader aspects and patterns of the systems studied that might seem at first unrelated from other perspectives, and that a humanistic approach might not be suited to explore.

Crucially for attempting this numerical approach, the last decades have seen a dramatic advance in the amount and availability of relevant data; new analytical and interpretive methods; more computational power and open access platforms all of which have fostered new research questions. These have enabled the creation of the multidisciplinary platforms necessary to ask new questions or to deploy statistical and quantitative data in new and innovative ways (Kandler & Powell, 2018; Crema et al., 2016; Lane & Gantley, 2018). Most importantly, the data currently available is of a quantitatively and qualitatively higher order than anything available before (Gantley et al., 2018; Cobo et al., 2019), facilitating a closer relationship between the physical and social sciences. Yet, substantial issues of interpretation and method have remained unaddressed, as it is the case for cultural loss where, although the impact of demographic, climate, and environmental shocks on human social organization has been debated for many decades. These issues and their impact have hardly been added in modeling and addressed from a data perspective (Turchin et al., 2018). Essentially, oversimplification of the causal connections between cultural change and environment (Ahedo et al., 2019) make it necessary to rethink how Social and Natural sciences can build transdisciplinary research, this without ignoring the principles of research and analysis upon which both are founded.

The aim of most researchers is to gather data of enough accuracy to test the models and narratives proposed. Accordingly, CLUB-DECES will estimate which are the best strategies to focus on when improvement for the data is required, i.e. identifying the minimum requirements in terms of noise (measurement uncertainty), systematic errors (hyper–parameters), imperfect knowledge of the system (nuisance parameters), modelling uncertainty (model comparison and model averaging), completeness and gaps (missing parts of the dataset), resolution (data-points per time and space), sample size, outliers and others. These levels of accuracy have to be achieved in order to test the models (Font-Ribera et al., 2012; Font-Ribera & Miralda-Escudé, 2012; Anders et al., 2016). This will be done for both individuals as well as a combination of datasets. To achieve that, one has to merge crucial expertise from multiple fields, using state-of-the-art tools and skills binged from expertise in model fitting methods from cosmology (Arinyo-i-Prats et al., 2015), ‘big data’ analysis (Arinyo-i-Prats et al., 2018) and observational thresholds estimation (Lee et al., 2014) plus complex and dynamical systems. Combining these approaches would result in an entirely novel investigation that pushes the methodological and empirical envelope.

6. Phases of the Research

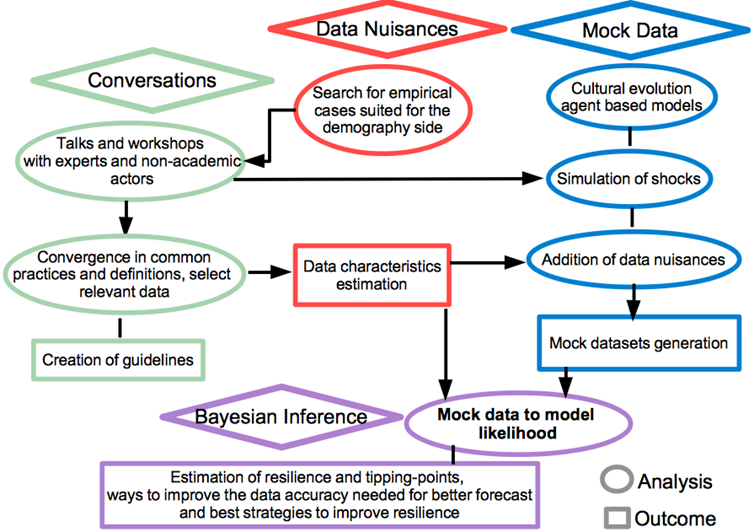

The main objective of this research is to establish cultural loss as a field of research and concern for the academic world and the wider society. In order to achieve this, the work shall be conducted in four interrelated phases (see Figure 1 for a summary of the methodology):

- Communication with experts and affected communities to gather or generate datasets that are meaningful for the proposed research in cultural loss affected by shocks, both from historical and current data. In this endeavour, the focus must be on the identification of nuisances, errors, problems of interpretation, different data gathering practices, biases and other effects that could potentially have a detrimental effect on the findings of the study.

- Selection, creation and elaboration of mock datasets by the application of agent based models that allow introducing shocks, and the data characteristics of the data sets studied in the previous phase. The generation of artificial datasets is necessary for the accurate analysis of the data, as mock data both to be used in the next step, as an integral part of the Bayesian inference, and allows one to have a more nuanced understanding of which are the errors in the data that have the biggest effect on the accuracy of the research outcomes.

- Estimation of the resilience of cultural traits and the tipping-points that trigger it for cultural communities by the application of Bayesian statistical methods already developed for other fields, specially cosmological studies. This approach allows one to compare models and datasets, providing a confidence level of how well the models are able to reproduce the available data, and constraining power of the datasets used. Moreover, by the use of mock datasets, it allows to forecast which are the best practices to improve both modelling and data gathering practices.

- Sharing with the wider scientific community and social sphere to interpret and integrate the results of the study into decision-making involving cultural heritage resilience. This will be achieved by conducting regular meetings and creating guidelines together with all the concerned agents to guide our data gathering routines, participate in the decision-making with informed numerical estimates and communicate with the wider public the importance of cultural heritage resilience and which strategies are best suited for that endeavour.

7. Conclusions

This work highlights the need to focus on the study of cultural loss driven by shocks, and how transdisciplinary approach is needed to tackle it. I have shown the relevance of cultural loss, a significant topic recognized internationally and collectively, which shapes our world but which has been until now grossly overlooked. Moreover, I motivated why resilience has to be studied against shocks to disentangle it from other evolutionary processes and to better have an idea of the resilience of current susceptible communities. Finally, I have illustrated a structured approach to numerically estimate the community’s tipping-points that might trigger cultural loss, and how to interpret and communicate the whole process and outcomes.

To address the numerical challenge, I take advantage of the unprecedented progress of data compilation, computational capacities and numerical techniques developed in the last decades to propose a feasible approach to the tipping points that trigger cultural loss in different communities. Through the text I have divided in steps the process needed for assessing one specific objective: to understand the resilience of culture against shocks. Each of the steps illustrates the need to engage the expertise in different disciplines, and a profound conversation to settle into topics and concepts shared by all the experts and non-academic actors involved. Once a common agreement and understanding can be established, universal or general guidelines can be created in order to use basic concepts as interchangeable proxies to be fed into a data processing machinery, machinery that has been already developed and optimized for another field of study, cosmology. Using the methodology routinely applied there, significant questions and progress can be achieved in the necessary disciplines involved.

The main goal of the research is to place the cultural loss debate into the general agenda, endeavours like these do not only have the duty to create bridges between the researchers of multiple disciplines and communities affected, but also have regular outreach with the wider society through the contact with journalists, social media, policymakers, NGOs and organizations and the general public to raise awareness about the problematic being addressed. This communication and awareness has to be effectively achieved thanks to the unitary mental framework created in a deeply transdisciplinary project, where the academic experts as well as the affected communities, associations and governmental agents, have the capacity to understand each other. This would facilitate the endeavour of transmitting the relevance of this topic to the wider society. It is of utmost importance to improve the resilience of culture against future shocks. We are currently experiencing heavy shocks, but others, similar to historical ones, might yet arise. This work will provide a way of understanding the past to have an influence in the future.

References

Ahedo, V., Caro, J., Bortolini, E., Zurro, D., Madella, M., and Galán, J. M. (2019). Quantifying the relationship between food sharing practices and socio-ecological variables in small-scale societies: A cross-cultural multi-methodological approach.PloS one, 14(5).

Anders, F., Chiappini, C., Rodrigues, T., Piffl, T., Mosser, B., Miglio, A., Montalba ́n, J., Girardi, L., Minchev, I., Valentini, M., et al. (2016). Galactic archaeology with corot and apogee: Creating mock observations from a chemodynamical model. Astronomische Nachrichten, 337(8-9), 926–930.

Aoki, K. (2018). On the absence of a correlation between population size and ‘toolkit size in ethnographic hunter–gatherers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1743), 20170061.

Arinyo-i Prats, A., Mas-Ribas, L., Miralda-Escudé, J., Pérez-Rafols, I., and Noterdaeme, P. (2018). A metal-line strength indicator for damped lyman alpha (dla) systems at low signal-to-noise. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 481(3), 3921– 3934.

Arinyo-i Prats, A., Miralda-Escudé, J., Viel, M., and Cen, R. (2015). The non-linear power spectrum of the lyman alpha forest. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2015(12), 017.

Biesele, M., Bleek, D. F., Jones, N. B., Cashdan, E. A., Denbow, J. R., Draper,P., Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I., Fourie, L., Guenther, M., Harpending, H., et al. (2013). Electronic human relations area files.Human Relations Area Files, New Haven. http://hraf. yale. edu

Borgerhoff Mulder, M., Nunn, C. L., and Towner, M. C. (2006). Cultural macroevolution and the transmission of traits. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 15(2), 52–64.

Boyd, R., Richerson, P. J., and Henrich, J. (2011). The cultural niche: Why social learning is essential for human adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 2), 10918–10925.

Brakes, P., Dall, S. R., Aplin, L. M., Bearhop, S., Carroll, E. L., Ciucci, P., Fishlock, V., Ford, J. K., Garland, E. C., Keith, S. A., et al. (2019). Animal cultures matter for conservation. Science, 363(6431), 1032–1034.

Cobo, J. M., Fort, J., and Isern, N. (2019). The spread of domesticated rice ineastern and southeastern asia was mainly demic. Journal of Archaeological Science, 101, 123–130.

Collard, M., Vaesen, K., Cosgrove, R., and Roebroeks, W. (2016). The empirical case against the ‘demographic turn in palaeolithic archaeology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150242.

Companion, M. (2015). Disaster’s Impact on Livelihood and Cultural Survival: Losses, Opportunities, and Mitigation. CRC Press.

Crema, E. R., Kandler, A., and Shennan, S. (2016b). Revealing patterns of cultural transmission from frequency data: Equilibrium and non-equilibrium assumptions. Scientific reports, 6, 39122.

Day, P. A. (2016). Indigenous peoples and cultural survival. In Encyclopedia of SocialWork.

De Walque, D. (2004). The long-term legacy of the Khmer Rouge period in Cambodia. The World Bank.

Dornelas, M., Antao, L. H., Moyes, F., Bates, A. E., Magurran, A. E., Adam,D., Akhmetzhanova, A. A., Appeltans, W., Arcos, J. M., Arnold, H., et al. (2018). Biotime: A database of biodiversity time series for the anthropocene. Global Ecology and Biogeography,27(7), 760–786.

Dryzek, J. S., Norgaard, R. B., and Schlosberg, D. (2011). The Oxford handbook of climate change and society. Oxford University Press.

Fogarty, L., Wakano, J. Y., Feldman, M. W., and Aoki, K. (2017). The driving forces of cultural complexity. Human Nature, 28(1), 39–52.

Font-Ribera, A., McDonald, P., and Miralda-Escude ́, J. (2012). Generating mock data sets for large-scale lyman-α forest correlation measurements. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2012(01), 001.

Font-Ribera, A. and Miralda-Escude ́, J. (2012). The effect of high column density systems on the measurement of the lyman-α forest correlation function. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2012(07), 028.

Gantley, M., Whitehouse, H., and Bogaard, A. (2018). Material correlates analysis (mca): An innovative way of examining questions in archaeology using ethnographic data. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 6(4), 328–341.

Haidle, M. N., Conard, N. J., and Bolus, M. (2016). The Nature of Culture: Basedonan Interdisciplinary Symposium‘The Nature of Culture’,Tu ̈bingen, Germany. Springer.

Henrich, J. (2004). Demography and cultural evolution: How adaptive cultural processes can produce maladaptive losses: The tasmanian case. American Antiquity, 69(2), 197– 214.

Ianni, E., Geneletti, D., and Ciolli, M. (2015). Revitalizing traditional ecological knowledge: A study in an alpine rural community. Environmental management, 56(1), 144–15.

INTER-SESSIONAL, A. H. O.-E. (2005). Convention on biological diversity.

Kandler, A. and Powell, A. (2018). Generative inference for cultural evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1743), 20170056.

Kirby, K. R., Gray, R. D., Greenhill, S. J., Jordan, F. M., Gomes-Ng, S., Bibiko, H.-J., Blasi, D. E., Botero, C. A., Bowern, C., Ember, C. R., et al. (2016). D-place: A global database of cultural, linguistic and environmental diversity. PLoS One, 11(7), e0158391.

Kuhl,H.S., Boesch,C., Kulik,L., Haas,F., Arandjelovic,M., Dieguez,P., Bocksberger, G., McElreath, M. B., Agbor, A., Angedakin, S., et al. (2019). Human impact erodes chimpanzee behavioral diversity. Science, 363(6434), 1453–1455.

Lane, J.E .and Gantley, M.J. (2018). Utilizing complex systems statistics for historical and archaeological data. Journal of Cognitive Historiography, 3(1-2), 68–92.

Lee, K.-G., Hennawi, J. F., Stark, C., Prochaska, J. X., White, M., Schlegel, D. J., Eilers, A.-C., Arinyo-i Prats, A., Suzuki, N., Croft, R. A., et al. (2014). Lyα forest tomography from background galaxies: The first megaparsec-resolution large-scale structure map at z¿ 2. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 795(1), L12.

Lemus, J. E. (2004). El pueblo pipil y su lengua.Científica, 5, 7–28.

Mackerras, C. (1973). Chinese opera after the cultural revolution (1970–72). The China Quarterly, 55, 478–510.

McGregor, D. (2008). Linking traditional ecological knowledge and westernscience: Aboriginal perspectives from the 2000 state of the lakes ecosystem of the lakes. Ecosystem conference. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 28(1), 139–158.

Mesoudi, A. (2016). Cultural evolution: a review of theory, findings and contro-versies. Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), 481–497.

Pitheckoff, N. (2017). Aging in the republic of Bulgaria. The Gerontologist,57(5), 809–815.

Polo, S., Tardío, J., Vélez-del Burgo, A., Molina, M., and Pardo-de Santayana,M. (2009). Knowledge, use and ecology of golden thistle (scolymus hispanicus l.) in central spain. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 5(1), 42.

Premo, L. S. and Kuhn, S. L. (2010). Modeling effects of local extinctions on culture change and diversity in the paleolithic. PLoS One, 5(12), e15582.

Reyes-García, V., Gue`ze, M., Luz, A. C., Paneque-Ga ́lvez, J., Macía, M. J., Orta-Mart ́ınez, M., Pino, J., and Rubio-Campillo, X. (2013). Evidence of traditional knowledge loss among a contemporary indigenous society. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(4), 249–257.

Riede, F. (2014). Towards a science of past disasters. Natural hazards, 71(1), 335–362.

Riede, F. (2017). Past-forwarding ancient calamities. pathways for making archaeology relevant in disaster risk reduction research. Humanities, 6(4), 79.

Rorabaugh, A. N. (2014). Impacts of drift and population bottlenecks on the cultural transmission of a neutral continuous trait: an agent based model. Journal of Archaeological Science, 49, 255–264.

“Ruritage: Rural Regeneration through Systemic Heritage-led Strategies.” Accessed 25 March 2019. https://www.ruritage.eu

Shennan, S. (2001). Demography and cultural innovation: a model and its implications for the emergence of modern human culture. Cambridge archaeological journal, 11(1), 5– 16.

Stump, D., Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C., Doolittle, W. E., Gnecco, C., Herrera, A., Pikirayi, I., Sillar, B., Spriggs, M., and Stump, D. (2013). On applied archaeology, indigenous knowledge, and the usable past. Current Anthropology, 54(3), 000–000.

Trotta, R. (2008). Bayes in the sky: Bayesian inference and model selection in cosmology. Contemporary Physics, 49(2), 71–104.

Turchin, P., Brennan, R., Currie, T. E., Feeney, K. C., Francois, P., Hoyer, D., Manning, J. G., Marciniak, A., Mullins, D. A., Palmisano, A., et al. (2015). Seshat: The global history databank. Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution.

Turchin, P., Witoszek, N., Thurner, S., Garcia, D., Griffin, R., Hoyer, D., Midt-tun, A., Bennett, J., Myrum Næss, K., and Gavrilets, S. (2018). A history of possible futures: Multipath forecasting of social breakdown, recovery, and resilience. Cliodynamics, 9(2).

United Nations Educational, S. and (UNESCO), C. O. (2003). Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage.

Whyte, K. P. (2013). On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: a philosophical study. Ecological processes, 2(1), 7.