Marco Madella

Marco Madellaabc

a CaSEs Research Group (Complexity and Socio-Ecological Dynamics), Department of Humanities – Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

b ICREA Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain.

c School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

The development of such a blue sky, innovative and long-term project is not without challenges that can arise from external and internal causes.

External challenges:

- CSIC “financial crisis”

- High bureaucracy for project management

Internal difficulties/problems:

- Coordination of research objectives

The external challenges were fundamentally related to dynamics and occurrences that happened outside the actual project but they have influenced it and are mostly related to the general management of the project. A general non-foreseeable factor that played an important role during the development of the project was that the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) entered a deep financial crisis at the end of 2012 and, due to serious budgetary problems, the Central Services blocked any expenditure for most part of the year 2013. This meant that the project was not able to carried out hiring or manage the normal expenditures related to such a major undertaking as a CONSOLIDER project. In this sense the project has not been “shielded” from the host institution problems and for such reason suffered delays in its development.

Another factor that created in many instances a certain overburden in terms of administrative work was the extreme bureaucratic approach in the day to day running of the project. An example of such administrative burden that was felt by most PIs as well as the coordinator was the necessity to communicate and receive the approval from the concerned Ministry for each personnel profile that was going to be enrolled in the project (both as participating researcher or as a researcher directly paid with CONSOLIDER funds). This process was creating much extra paperwork for the PIs, the coordinator as well as for the administrative personnel, and it was slowing down the active participation of the different researchers involved in the project.

Part of the high bureaucratic burden was also originated directly by the project coordinating Institution, the CSIC (Spanish National Research Council), specifically in the area of hiring the CONSOLIDER personnel. The CSIC hiring system follows the rules of a state institution with preset hiring channels for contracting within or without the National Agreement Contract (convenio) as well as internal procedures with several steps of control (institute administration –gerencia- as well as the “bolsa de trabajo” with its own committees countersigning the validity of the candidates documents, the Human Resources department centralised in the administration in Madrid, etc). The hiring, therefore, and especially the hiring through the National Agreement Contract (convenio), meant an incredibly long time from the moment it was taken the decision of hiring a researcher/technician due to a specific need of the project and the moment the selected person could have actually started her/his contract. Sometime, this delay between the need of hiring and the actual hiring amounted to up to five months. This delay meant that there was not sufficient flexibility to adapt the hiring strategy to the research needs, which are often developing and changing quickly in such a complex project. All hiring therefore needed to be organized well in advance to be sure personnel and research were effectively coordinated but it was difficult to cover arising necessities.

The internal challenges arose mostly from research problems experienced during the development of the project’s research lines and the creation of synergies between different groups. A difficulty encountered by the project coordinator (as well as the Scientific Committee) was to be able to maintain the focus of each group participating in the CONSOLIDER project on the project’s aims and goals, beyond the focus that the PIs had in relation to each case study and their specific research questions. Fundamentally, the difficulty was in deepening the crosscutting collaboration and overcoming disciplinary and knowledge boundaries. This is why the coordinator activated several and repetitive meetings with the PIs for each research group as well as working meetings, seminars, etc. with all PIs. This strategy partially helped in continuously cantering the attention onto the project’s goals (often more theoretical and methodological) than the single case study goals (often more practical and related to interests connected to the specific research line developed within each group). When the project was about half way (end of 2013) it became clear that to be able to maintain the synergies between the groups the project should move from being based on case studies to major, agglutinating research themes.

With this in mind, the case studies were integrated into thematic clusters: Cooperation, Resilience and Cultural Transmission. Each one of these themes brought together different research groups, methodologies and specific problems to be solved. Thus, it was hoped not only to continue the research established in each case study but also to better define common research areas that crossed methodologies and disciplines. Following this new road map, the aim was to transcend any kind of historical particularism (so often affecting historical research), establishing a different scale of analysis and delving into anthropological, sociological or historical questions of a more general («mid-range») type, whose approach represented a real methodological advance for the Sciences Social, and being also of greater interest for the wider scientific community.

Although the foundations for the development of thematic clusters were set in place from the end of 2013, the development of such clusters has proved more complex than expected (both at research and staff coordination levels) due to:

1) The uneven level of advance of the different groups, which was related to:

- Personnel moving to different positions as part of the usual dynamics of the academic world. In some groups a number of the contracted researchers opted for semi-permanent or permanent positions in other institutions.

- The transdisciplinary character of the project and the need to enrol hybrid profiles has often made it difficult to find the right personnel. The training of hybrid profiles has also proved difficult. In more than one occasion we have faced the impossibility of co-supervise theses from different departments in different universities due to the current regulation system.

2) The difficulty inherent to certain cases of study, which in some occasions required an intense preliminary work for the elaboration of the database.

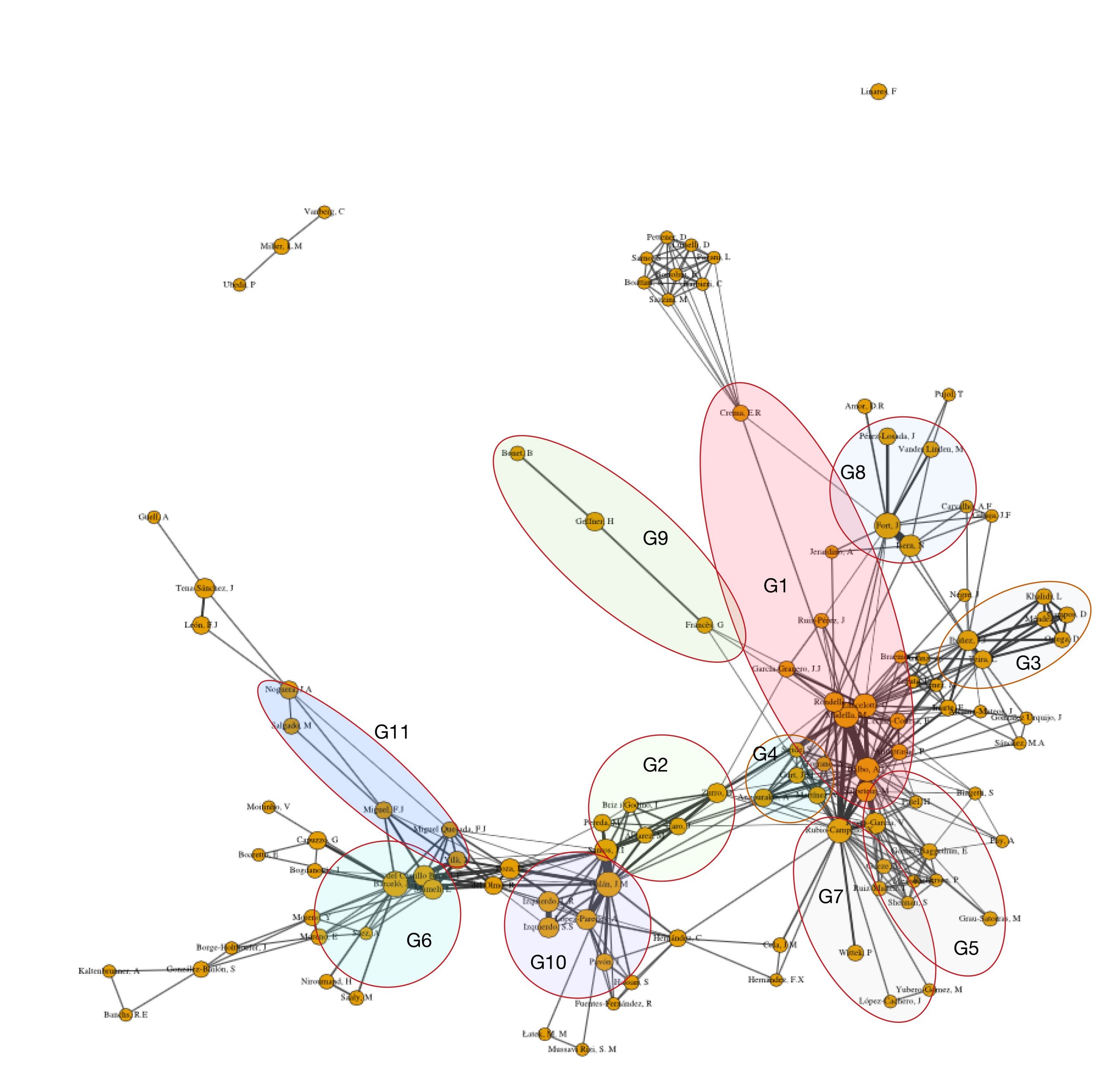

From the perspective related to the transdisciplinary development pursued by SimulPast, several researchers were involved during the lifetime of the project. Indeed, almost one hundred personnel, between researchers, technical staff and PhD students took part in SimulPast. Some of the participants have been part of the project for the whole lifetime while others only for a shorter period of time. This meant a continuous interchange between disciplines and the creation of a common area of work. To illustrate the level of interconnectivity and to highlight areas of development, we carried out a network analysis of the collaborative publications arising from SimulPast (Figure 1). These should be taken as representative of the intensity and frequency of collaborative efforts generated by the project. The coloured areas show the concentration of authors according to group, the intensity (thickness) of the connecting lines depends on the number of common publications. It is clear from this analysis that the collaborative dynamics did not develop equally in all groups participating in the project and that a “common ground” for developing a transdisciplinary approach was embraced in different ways by the different PIs.

The “take home message” from the personal experience of coordinating a CONSOLIDER project, and from analysing its dynamics and outcomes, can be articulated on the administrative and scientific levels. From an administrative point of view, projects of such as those of the CONSOLIDER programme, which somehow mirrored the cooperation projects of the EU R+D programme, are an important part of an effective state run R+D strategy but they should be allowed higher flexibility in management during their development. The hiring system should be less cumbersome and acquire a level of agility matching the need of research developments and new challenges arising during the project lifetime. A very relevant example is the current pandemic of COVID19 and the research arising from such a situation. A CONSOLIDER project focusing on research on viruses that already running would have had difficulties in its ability to respond and adapt quickly to the new environment and the need of new experiments, setting up new sub-groups and, of course, hiring new personnel. From a scientific level, the coordination of a CONSOLIDER project implied often the reassessment of the single groups dynamics to avoid the groups “spinning off” in directions not specifically covering the project’s goals. A more centralised management of the resources might facilitate maintaining the focus.