“To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.” – Aristotle, The Metaphysics

All arguments begin with questions. “Is this right or wrong?” “Are we getting anywhere?” “Do you think that…?” Sometimes, the questions are subtle, implied in media we’re consuming, the work we’re completing, or the activity in which we’re participating. “Built Ford tough,” a commercial claims — but what is “Ford tough”? Is it good? Should we care?

Sometimes, the questions — and arguments — are the opposite of subtle, as we often see during contentious elections or public controversies.

In academics, we set aside time and space to learn about and practice argument because we value the ability of a writer, reader, and thinker to ethically prove their point. Whether it is piping up with an opinion during class discussion or writing a heart-felt personal essay about the reasons for attending school, argument motivates much of the work you’ll do in college. It is also behind nearly every piece of media — written, spoken, musical, video, or other — that you’ll encounter both within and beyond your college’s walls.

Therefore, before we can craft arguments, we need to understand how to define argument. We also need to understand more about what makes an argument believable. Why do we trust certain sources and not others? Why do we (or should we) listen more to some voices or value some viewpoints over their counterparts?

Part of understanding how to write in and for college involves learning what sources — what type of material, from what locations, published through what media channels, by which authors — will be considered most reliable by your peers and professors. However, college should also be a time when you figure out what sources you find reliable personally, and investigate whether your trust is well placed or not. This first section dives into the definitions that we use, both as academic writers and as regular, everyday media consumers, for fact and opinion, and then it tries to unwind what we consider to be believable resources in academia — definitions that are ever-changing and, as you’ll see, open to argument.

So let’s start with the big questions. What is a fact?

It seems simple, doesn’t it? Dictionaries (like the American Heritage Dictionary.Com entry) provide us with boring descriptions:

- something that actually exists; reality; truth

- something known to exist or to have happened

- a truth known by actual experience or observation; something known to be true

- something said to be true or supposed to have happened

Let’s consider these definitions in turn as they seem to provide some wiggle room.

The first definition, “Something that actually exists,” might seem obvious when we’re thinking about a house or a pink elephant, but what about when we’re talking about concepts? Does fear actually exist? What about panic? Is it a fact that a child is afraid of the dark, or is it just the child’s opinion that the dark is scary?

Maybe the second definition is more helpful: if something is “known to exist or to have happened,” then it’s a fact. However, experience differs. If I’ve never been afraid of the dark, do I believe that fear of the dark is possible, that it’s true? Who decides what is “known to exist”? If it’s left to each person to decide, then we’re looking at a world where every fact could be true for one person and false for the next.

The third definition says facts are “truth known by actual experience or observation,” which reminds us of the old “seeing is believing” idea. Anyone with access to a digital camera and an image editor knows, however, that even photographic evidence can be deceiving, and the line of children waiting to see Santa Claus at the mall every December might be good proof that sometimes (spoilers!), we see things that later aren’t what they seem.

What about actual experiences, though? Those would certainly seem to prove something. Here, again, we rely on perception: think of court cases that rely on witness testimony. Two people can often see the same series of events and believe that different things happened. Does this change what was a fact?

So what about the fourth definition, then? Is a fact something that we’re told will be true? If so, who do we trust to tell us? I’ve been told Salem is the capital of Oregon by many sources, but I’ve never tried to prove it myself. Do I take a teacher’s word? The encyclopedia? Google Maps? The Internet? Do I need to see the actual original bill signed into law 150 years ago?

This might seem like a silly debate. Many of us generally think we know facts when we see them, without bothering with a dictionary definition. However, in argument, what you can prove is what you can use, and proof relies on what you believe to be true (and what your audience will also trust). Remember: much of what you’ll be asked to write about in college will rely on your interpretation of the material in front of you. That’s true when we’re looking at literature (is it a fact that The Old Man and the Sea is a classic, or is it opinion?) and when we’re talking about science (does a patient’s report of his own symptoms reflect a fact or an opinion? Does the nurse’s report count as fact?).

The difficulty of defining what is fact can pose a particular challenge in our daily, Internet-connected, social-media-immersed life. Articles that look like news — like fact — can often end up containing substantial amounts of opinion or reflecting personal bias. In fact, an article from one publication may seem like fact to one reader and opinion to another. So how do we know what is fact and what is opinion? How do we know what sources to trust and what sources to question? The short answer is that we don’t know without investigating.

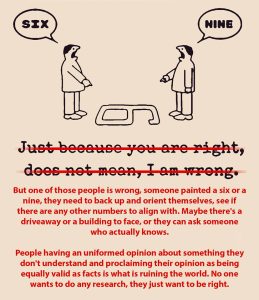

Consider the comic at the right, which circulated the Internet at the end of 2016 and start of 2017. “Just because you are right does not mean I am wrong,” it says, and many viewers and commenters found this to be comforting and true. However, as the edited version points out, sometimes there are right answers; sometimes, it takes investigation to find those answers, instead of just settling into an “agree to disagree” relationship. Investigation requires an open mind — and this is what academic argument wants most from its writers. We want you to explore for answers with curiosity instead of bias.

Most of what you’ll be asked to write in college is based in argument. To succeed academically, one must be able to write a clear, smart argument based on evidence. When we talk about argument, what we’re really talking about is this process: the process of starting with a question and then exploring and investigating to find answers that are believable for our audience (and ourselves). Before we can write a clear argument, however, we need to know some argument terms, and we need to know how to identify good (and not-so-good) arguments made by others. The next section of this book will introduce you to those concepts.