38

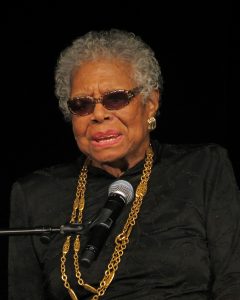

Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

Maya Angelou was an American poet, memoirist, actress and an important figure in the American Civil Rights Movement. Angelou is known for her series of six autobiographies, starting with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, (1969) which was nominated for a National Book Award and called her magnum opus. Her volume of poetry, Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water ‘Fore I Diiie (1971) was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

Angelou recited her poem, “On the Pulse of Morning” at President Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993, the first poet to make an inaugural recitation since Robert Frost at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961. She was highly honored for her body of work, including being awarded over 30 honorary degrees.

Angelou’s first book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sing, describes her early life and her experience of confronting racism, a central feature of her work. She used the caged bird as a metaphor for the imprisoning nature of racial bigotry on her life.

At the time of her death, tributes to Angelou and condolences were paid by artists, entertainers, and world leaders, including President Barack Obama, whose sister had been named after Angelou, and former President Bill Clinton. Harold Augenbraum, from the National Book Foundation, said that Angelou’s “legacy is one that all writers and readers across the world can admire and aspire to.”

Interview with Oprah Winfrey “Caged Bird”:

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings“

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Film:

“Phenomenal Woman“

Listen to Maya Angelou recite “Phenomenal Woman”:

Attributions:

- “Maya Angelou” from New World Encyclopedia licensed CC BY SA.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a poet who inspired devotion. In the present day, it is worth remembering that some poets were celebrities on the level of modern day actors and musicians, with fan followings, fan letters, and requests for autographs. The public admired her politics as well as her artistry; she wrote abolitionist poems, and works such as “The Cry of the Children” (1842) are believed to have created popular support for child labor laws passed in 1844.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a poet who inspired devotion. In the present day, it is worth remembering that some poets were celebrities on the level of modern day actors and musicians, with fan followings, fan letters, and requests for autographs. The public admired her politics as well as her artistry; she wrote abolitionist poems, and works such as “The Cry of the Children” (1842) are believed to have created popular support for child labor laws passed in 1844.

One of her admirers was the poet Robert Browning: six years younger than she was and not yet famous. In his first letter to her in January 1845 (over five hundred of their letters survive), he declares his love not only of her poems, but of her. At that point, Elizabeth had been an invalid for years, for some time confined in her room by a controlling father who refused to allow any of his twelve children to marry. Twenty months later, Robert and Elizabeth eloped (her father disowned her), traveling to Italy, where Elizabeth recovered some of her health and gave birth to their son in 1849.

During those early years, the love poems that she wrote to Robert became Sonnets from the Portuguese; unlike her other poetry, Elizabeth was hesitant at first to admit that she wrote the passionate poems, originally claiming that she had simply translated them from a Portuguese collection. She continued to write on a full range of topics, including the most popular work in her lifetime, the verse-novel Aurora Leigh. She died after another bout of illness in Florence, Italy, in the arms of her husband.

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

Sonnets From the Portuguese

Robert’s nickname for Elizabeth was “my little Portuguese,” making this collection all the sweeter. Sonnet 33 and 43 and the most famous of this collection of sonnets. Click here to read the rest of them.

XXXIII

Yes, call me by my pet-name! let me hear

The name I used to run at, when a child,

From innocent play, and leave the cowslips plied,

To glance up in some face that proved me dear

With the look of its eyes. I miss the clear

Fond voices which, being drawn and reconciled

Into the music of Heaven’s undefiled,

Call me no longer. Silence on the bier,

While I call God—call God!—so let thy mouth

Be heir to those who are now exanimate.

Gather the north flowers to complete the south,

And catch the early love up in the late.

Yes, call me by that name,—and I, in truth,

With the same heart, will answer and not wait.

XLIII

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Attributions

- Poems licensed under Public Domain.

- “Elizabeth Barrett Browning” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II: Volume 5 and licensed under CC BY SA.

Robert Browning (1812-1889)

Robert Browning was an unknown poet when he fell in love with one of the most famous poets of his time, Elizabeth Barrett. Their relationship was the stuff of love poems; he fell in love with her, although he had never met her, by reading her poetry. At the time, she was an invalid who was kept pretty much a prisoner by her tyrannical father, who had decided never to allow any of his twelve children to marry. After a secret correspondence over twenty months, they eloped to Italy. She recovered enough of her health that she was able to give birth to a son, and they lived in Italy until her death in 1861.

It was really only after her death that Robert Browning started to acquire fame as a poet, eventually becoming one of the most respected poets of the Victorian era. Although he wrote poems and plays on a range of topics (including his romance with Elizabeth Barrett), some of his most famous poems are his dramatic monologues, often with narrators who have extreme or even psychotic personalities. At first, audiences were startled by the dark humor and occasionally grotesque situations in many of the monologues, unaccustomed to reading about the human psyche in this way. In “My Last Duchess,” the Duke addresses a silent representative of a Count whose daughter he wants to marry. The Duke is the epitome of an entitled snob, but his monologue slowly reveals that these qualities led him to become an unrepentant murderer, with a terrifying possessiveness that continues long after his first wife’s death. “Porphyria’s Lover” contains one of the best twists (the pun will become clear after reading it) in the monologues; it is again a study in psychotic self-absorption, as well as a technical triumph (try reading it without stopping at the end of the lines, but instead by stopping only at punctuation marks). The third monologue presented here is “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” a nightmarish quest with an ambiguous ending. The poem inspired many other writers, including Stephen King, who based his Dark Tower series (1978-2012) on the poem.

MEETING AT NIGHT

PARTING AT MORNING

PORPHYRIA’S LOVER

The rain set early in to-night,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

>When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneeled and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soiled gloves by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me—she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavor,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me forever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could to-night’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I looked up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last I knew

Porphyria worshipped me; surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string I wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily oped her lids: again

Laughed the blue eyes without a stain.

And I untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propped her head up as before,

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorned at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirred,

And yet God has not said a word!

MY LAST DUCHESS

“CHILDE ROLAND TO THE DARK TOWER CAME”

My first thought was, he lied in every word,

Now patches where some leanness of the soil’s

Attributions

- Poems licensed under Public Domain.

- “Robert Browning” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II and licensed under CC BY SA.

Stephen Crane (1871-1900)

Stephen Crane was an American novelist, poet, and journalist who is now considered to be one of the most important writers in the vein of American realism. In fiction, Crane pioneered a naturalistic and unsentimental style of writing that was strongly influenced by Crane’s experiences as a journalist. Crane’s most well-known work, The Red Badge of Courage, is almost universally considered to be the first great novel of the American Civil War, due in part to its ability to describe the experience of warfare in vivid, psychological detail. Crane’s other major novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, was less popular in its time, but it too is now esteemed as one of the most vivid portrayals of lower-class life in nineteenth century Manhattan in all of American literature. Crane’s focus on realistic stories, which often ended tragically and without a clear sense of resolution, were contrary to the Romantic tastes of his times, and it would not be until the next generation of American realists, such as Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris, that Crane’s immense influence on the development of American literature would become fully apparent.

“War is Kind”

Do not weep, maiden, for war is kind.

Because your lover threw wild hands toward the sky

And the affrighted steed ran on alone,

Do not weep.

War is kind.

Hoarse, booming drums of the

regiment,

Little souls who thirst for fight,

These men were born to drill and die.

The unexplained glory files above

them,

Great is the battle-god, great, and his

kingdom—;

A field where a thousand corpses lie.

Do not weep, babe, for war is kind.

Because your father tumbled in the yellow

trenches,

Raged at his breast, gulped and died,

Do not weep.

War is kind.

Swift blazing flag of the regiment,

Eagle with crest of red and gold,

These men were born to drill and die.

Point for them the virtue of the slaughter,

Make plain to them the excellence of killing

And a field where a thousand corpses

lie.

Mother whose heart hung humble as a button

On the bright splendid shroud of your son,

Do not weep.

War is kind.

Attributions

- Poem in the Public Domain.

- “Stephen Crane” from New World Encyclopedia, licensed under CC-by-sa 3.0 License.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Now one of the best-known American poets, Emily Dickinson was not known during her lifetime; ten poems were published anonymously, and the rest were published after her death. Dickinson’s poetry resists easy categorization within literary movements. Traditionally Romantic themes such as nature and passion are presented in the startlingly direct—or even blunt—manner of Realism; while not truly Transcendentalist, the poems concern themselves with finding meaning in one’s self, rather than in material possessions or earthly concerns; her unconventional use of language, punctuation, and approximate rhyme (or “slant rhyme’) rejects traditional styles in the way that later Modernists would embrace. In fact, it was only with the advent of Modernism that Dickinson’s poems received the kind of widespread acclaim for their innovation and daring that would mark her as one of the most significant poets of the 19th century.

Now one of the best-known American poets, Emily Dickinson was not known during her lifetime; ten poems were published anonymously, and the rest were published after her death. Dickinson’s poetry resists easy categorization within literary movements. Traditionally Romantic themes such as nature and passion are presented in the startlingly direct—or even blunt—manner of Realism; while not truly Transcendentalist, the poems concern themselves with finding meaning in one’s self, rather than in material possessions or earthly concerns; her unconventional use of language, punctuation, and approximate rhyme (or “slant rhyme’) rejects traditional styles in the way that later Modernists would embrace. In fact, it was only with the advent of Modernism that Dickinson’s poems received the kind of widespread acclaim for their innovation and daring that would mark her as one of the most significant poets of the 19th century.

Although she spent most of her adult life in seclusion in her family’s home in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson maintained contact with the outside world through her letters, over a thousand of which have survived. After her death, Dickinson’s family published the almost 1800 poems that she had written; most of the poems were not titled, and editors have had to choose how to organize the poems.

The poems often use common meter as a starting point (a pattern of an eight syllable line followed by a six syllable line, sometimes referred to as hymn meter), but develop other patterns—or lack of pattern—from there.

Dickinson’s poems often surprise the reader: the poem “A Bird came down the Walk” begins with a Romantic subject—nature—but switches quickly to a slightly gross realism. Poems such as “Because I could not stop for Death” approach serious subjects with unexpected humor. Her unusual approaches to common themes such as love, death, nature, and identity remain engaging to readers to the present day.

Poems

Just a few of her 1500+ poems are included here. Visit here to read the rest.

SUCCESS.

[Published in “A Masque of Poets”

at the request of “H.H.,” the author’s

fellow-townswoman and friend.]

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne’er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple host

Who took the flag to-day

Can tell the definition,

So clear, of victory,

As he, defeated, dying,

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Break, agonized and clear!

IN A LIBRARY.

A precious, mouldering pleasure ‘t is

To meet an antique book,

In just the dress his century wore;

A privilege, I think,

His venerable hand to take,

And warming in our own,

A passage back, or two, to make

To times when he was young.

His quaint opinions to inspect,

His knowledge to unfold

On what concerns our mutual mind,

The literature of old;

What interested scholars most,

What competitions ran

When Plato was a certainty.

And Sophocles a man;

When Sappho was a living girl,

And Beatrice wore

The gown that Dante deified.

Facts, centuries before,

He traverses familiar,

As one should come to town

And tell you all your dreams were true;

He lived where dreams were sown.

His presence is enchantment,

You beg him not to go;

Old volumes shake their vellum heads

And tantalize, just so.

THE WIFE.

She rose to his requirement, dropped

The playthings of her life

To take the honorable work

Of woman and of wife.

If aught she missed in her new day

Of amplitude, or awe,

Or first prospective, or the gold

In using wore away,

It lay unmentioned, as the sea

Develops pearl and weed,

But only to himself is known

The fathoms they abide.

XV.

I’ve seen a dying eye

Run round and round a room

In search of something, as it seemed,

Then cloudier become;

And then, obscure with fog,

And then be soldered down,

Without disclosing what it be,

‘T were blessed to have seen.

THE CHARIOT.

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me;

The carriage held but just ourselves

And Immortality.

We slowly drove, he knew no haste,

And I had put away

My labor, and my leisure too,

For his civility.

We passed the school where children played,

Their lessons scarcely done;

We passed the fields of gazing grain,

We passed the setting sun.

We paused before a house that seemed

A swelling of the ground;

The roof was scarcely visible,

The cornice but a mound.

Since then ‘t is centuries; but each

Feels shorter than the day

I first surmised the horses’ heads

Were toward eternity.

A SERVICE OF SONG.

Some keep the Sabbath going to church;

I keep it staying at home,

With a bobolink for a chorister,

And an orchard for a dome.

Some keep the Sabbath in surplice;

I just wear my wings,

And instead of tolling the bell for church,

Our little sexton sings.

God preaches, — a noted clergyman, —

And the sermon is never long;

So instead of getting to heaven at last,

I’m going all along!

VII.

The bee is not afraid of me,

I know the butterfly;

The pretty people in the woods

Receive me cordially.

The brooks laugh louder when I come,

The breezes madder play.

Wherefore, mine eyes, thy silver mists?

Wherefore, O summer’s day?

Attributions

- Poems is licensed under Public Domain.

- “Emily Dickinson” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II: Volume 5 and licensed under CC BY SA.

T. S. Eliot (1888-1965)

Eliot was born in St. Louis, the youngest of seven children. He attended Smith Academy in St. Louis, and went on to study at Harvard. After finishing his bachelor’s degree, he began his graduate studies. During this time, he focused on Symbolist poetry. He tried to study abroad in Germany in 1914, but left the country early due to the threat of war.

Instead, he went to England, where he met Ezra Pound, who would have a profound influence on Eliot’s work. While Eliot did occasionally return to the United States, he settled in England and eventually became a citizen of the country. It was Pound who helped Eliot publish “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915) in Poetry. The poem established Eliot’s reputation as an experimental, intellectual writer.

Eliot possessed an amazing versatility. By the time he was 40, he had published over 20 books, which included volumes of poetry, criticism, and plays. His most notable work is The Waste Land (1922), which explores the disenfranchisement and ennui felt by the post- World War I, Lost Generation. The work is experimental in its fracture perspectives, play with tone and language, and disrupted narrative. His criticism, most specifically works from The Sacred Wood, such as “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1920), constructs a comprehensive literary theory, where the poet is not merely repeating popular ideas, but is interacting with an entire body of literary history, starting with Homer. By the time he won the Nobel Prize in 1948, he was considered one of the most influential writers in the English language.

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

S'io credesse che mia risposta fosse

A persona che mai tornasse al mondo,

Questa fiamma staria senza piu scosse.

Ma perciocche giammai di questo fondo

Non torno vivo alcun, s'i'odo il vero,

Senza tema d'infamia ti rispondo.

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question….

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair—

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin—

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?

And I have known the eyes already, known them all—

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

And I have known the arms already, known them all—

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

(But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!)

Is it perfume from a dress

That makes me so digress?

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl.

And should I then presume? And how should I begin? . . . . . . . . .

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets

And watched the smoke that rises from the pipes

Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows?

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas. . . . . . . . . .

And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully!

Smoothed by long fingers,

Asleep… tired… or it malingers.

Stretched on the floor, here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet—and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal

Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it toward some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head,

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all; That is not it, at all.”

And would it have been worth it, after all,

Would it have been worth while,

After the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets,

After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor— And this, and so much more?—

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all, That is not what I meant, at all.” . . . . . . . . .

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

I grow old… I grow old…

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind?

Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black.

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

The Hollow Men

Attributions

- Poem in the public domain.

- “T.S. Eliot” from Compact Anthology of World Literature II and licensed under CC BY SA.

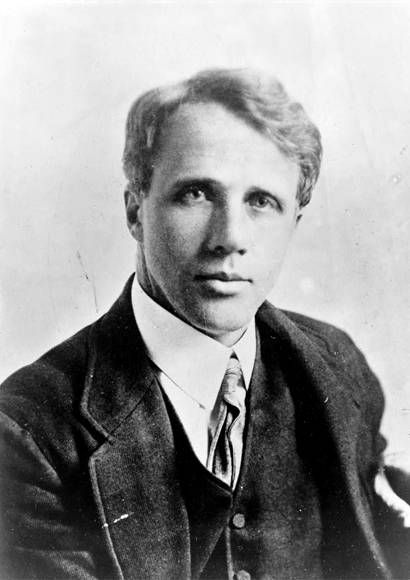

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Robert Lee Frost was an American poet, arguably the most recognized American poet of the twentieth century. Frost came of age during a time when modernism was the dominant movement in American and European literature. Yet, distinct from his contemporaries, Frost was a staunchly un-modern poet. He relied on the same poetic tropes that had been in use in English since poetry’s inception: Rhyme, meter, and formalized stanzas, wryly dismissing free verse by claiming, “I’d just as soon play tennis with the net down.”

Modernist poetry largely abandoned conventional poetic forms as obsolete. Frost powerfully demonstrated that they were not by composing verse that combined a clearly modern sensibility with traditional poetic structures. Accordingly, Frost has had as much or even more influence on present-day poetry—which has seen a resurgence in formalism—than many poets in his own time.

Frost endured much personal hardship, and his verse drama, “A Masque of Mercy” (1947), based on the story of Jonah, presents a deeply felt, largely orthodox, religious perspective, suggesting that man with his limited outlook must always bear with events and act mercifully, for action that complies with God’s will can entail salvation. “Nothing can make injustice just but mercy,” he wrote. Frost’s enduring legacy goes beyond his strictly literary contribution. He gave voice to American, and particularly New England virtues.

THE ROAD NOT TAKEN

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveller, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

FIRE AND ICE

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To know that for destruction ice

Is also great,

And would suffice.

Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Attributions

- “Robert Frost” from New World Encyclopedia licensed CC BY SA.

- Poems in the Public Domain.

Joy Harjo (1951-)

Joy Harjo (born in Tulsa, Oklahoma) is a critically acclaimed poet and musician, drawing on American Indian history and storytelling tradition. She is a member of the Mvskoke (aka. Muscogee, or Creek) nation; her father was a member of the Mvskoke tribe, and her mother was Cherokee, French, and Irish. In her work, she incorporates the history, myths, and beliefs of Native America (Creek in particular) as well as ideas that concern feminism, imperialism and colonization, contemporary America, and the contemporary world. Related to Native American storytelling is a sense of all things being connected, which often shapes her work. Inspired by the evolving nature of oral storytelling and ceremonial tradition, she integrates various forms of music, performance, and dance into her poetry, and has released award-winning CDs of original music. Her first volume of poetry was The Last Song (1975), and her other books of poetry include How We Became Human—New and Selected Poems (2004), The Woman Who Fell From the Sky (1994), and She Had Some Horses (1983). Her CD releases include Red Dreams, A Trail Beyond Tears (2010) and Winding Through the Milky Way (2008).

Perhaps the World Ends Here

Attributions:

- “Joy Harjo” from Compact Anthology of World Literature II and licensed under CC BY SA.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

A leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance in the United States, Langston Hughes developed an international reputation for his poetry. Hughes spent his childhood in the Midwest; he was born in Joplin, Missouri, but he also lived in Lincoln, Illinois and Cleveland, Ohio. As a young man, he began a college education at Columbia University, but withdrew to travel as a merchant seaman. He eventually completed his education at Lincoln University.

Hughes is particularly known for his perceptive portrayals of black life in America from the twenties through the sixties. He wrote prolifically and in a variety of genres–poems, plays, short stories, and novels. A significant feature of his work is the influence of jazz on his poetry, particularly in Montage of a Dream Deferred (Holt, 1951). Hughes also mentored other young poets and writers like Ralph Ellison. In 1926, he articulated the purpose of young black writers and poets in “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”: “The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful . . . If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves.”

Donald B. Gibson noted in the introduction to Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays (Prentice Hall, 1973) that Hughes “differed from most of his predecessors among black poets … in that he addressed his poetry to the people, specifically to black people.” Hughes considered himself to be, indeed, a “people’s poet” who elevated the black aesthetic while confronting racism and stereotypes in his work.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

“Mother to Son “

- Listen to Hughes reciting “Mother to Son”:https://youtu.be/NX9tHuI7zVo

- “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” licensed in the Public Domain.

- “Langston Hughes” adapted from Compact Anthology of World Literature II and licensed under CC BY SA.

Marge Piercy (1936-)

Marge Piercy was born in Detroit, Michigan, to Bert (Bunnin) Piercy and Robert Piercy. While her father was presbyterian, she was raised Jewish by her mother and maternal grandmother who gave Piercy the Hebrew name of Marah.

On her childhood and Jewish identity, Piercy said: “Jews and blacks were always lumped together when I grew up. I didn’t grow up ‘white.’ Jews weren’t white. My first boyfriend was black. I didn’t find out I was white until we spent time in Baltimore and I went to a segregated high school. I can’t express how weird it was. Then I just figured they didn’t know I was Jewish.”

Piercy was involved in the civil rights movement, New Left, and Students for a Democratic Society. She is a feminist, environmentalist, marxist, social, and anti-war activist. In 1977, Piercy became an associate of the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP), an American nonprofit publishing organization that works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Piercy is the author of more than seventeen volumes of poems, among them The Moon Is Always Female (1980, considered a feminist classic) and The Art of Blessing the Day (1999). She has published fifteen novels, one play (The Last White Class, co-authored with her current (and third) husband Ira Wood), one collection of essays (Parti-colored Blocks for a Quilt), one non-fiction book, and one memoir.

Piercy’s poetry tends to be highly personal free verse and often centered on feminist and social issues. Her work shows commitment to social change—what she might call, in Judaic terms, tikkun olam, or the repair of the world). It is rooted in story, the wheel of the Jewish year, and a range of landscapes and settings.

“Connections“

“To Be of Use“

Piercy reading “To Be of Use”

“Barbie Doll“

“What are Big Girls Made of“

- Biography adapted from “Marge Piercy” and licensed under CC BY SA 3.0.

Sylvia Plath (1932-1963)

Sylvia Plath was an American poet, novelist, short story writer, and essayist. She is most famous for her semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar and her advancements in confessional poetry building on the work of Robert Lowell and W.D. Snodgrass. Plath has been widely researched and followed since her controversial suicide. She has gained fame as one of the greatest poets of her generation. Widely read throughout the world, Sylvia Plath has risen to iconic status because of her emotional poetry dealing with loss and depression, and has thus touched many people struggling with the same feelings. In 1982, Plath became the first poet to win a Pulitzer Prize posthumously for The Collected Poems.

An interview with Sylvia Plath:

Daddy

Attributions:

“Sylvia Plath” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

Alberto Rios (1952-)

“Alberto Ríos, Arizona’s inaugural poet laureate and a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, is the author of eleven books and chapbooks of poetry, including The Theater of Night—winner of the 2007 PEN/Beyond Margins Award—three collections of short stories, and a memoir about growing up on the border, Capirotada. His book The Smallest Muscle in the Human Body was a finalist for the National Book Award. Ríos is the recipient of numerous accolades and his work is included in more than 300 national and international literary anthologies. He is also the host of the PBS program Books & Co. His work is regularly taught and translated, and has been adapted to dance and both classical and popular music. Ríos is a University Professor of Letters, Regents’ Professor, and the Katharine C. Turner Chair in English at Arizona State University. In 2017, he was named director of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing. His most recent book is A Small Story About the Sky.”

Nani

A House Called Tomorrow

Don’t Go Into the Library

Attributions

- “Alberto Rios” biography excerpted from Yavapai College Literary Southwest introduction.

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950)

Edna St. Vincent Millay was a lyrical poet and playwright and the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. During her own time, Millay was almost as famous for her unusual, Bohemian lifestyle and opinions on social matters as she was for her actual poetry. During much of her career she lived the life of a minor celebrity. In time, however, critical estimation of her poetry has caught up with her celebrity, and in recent decades it has become increasingly clear just how important Millay is for the history of early twentieth-century American literature.

Millay lived and wrote during the early decades of the twentieth-century, a period in which the literary Modernism of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound dominated American poetry. Millay, however, was a distinctly un-Modern poet whose works have much more in common with those of Robert Frost or Thomas Hardy; her poetry is always formal, masterfully written to the strictures of rhyme and meter. During her times a number of poets and critics argued fiercely over the form poetry should take in the rapidly changing times of the twentieth-century; Millay, for her part, was not particularly vocal in these debates, because her works speak for themselves.

Millay proved that the old forms could retain their validity in a changing world. Her sonnets are often considered to be the finest written in the twentieth-century, and her short, lyrical poems are unrivaled for their elegance and musicality. Millay’s influence extends to a number of poets of the latter twentieth-century, Elizabeth Bishop notably among them. Millay’s poetry provides a glimpse at another form of poetry, full of sweetness and light, that remained stable and clear throughout the turmoil of Modernism.

Eight Sonnets

I

When you, that at this moment are to me

Dearer than words on paper, shall depart,

And be no more the warder of my heart,

Whereof again myself shall hold the key;

And be no more, what now you seem to be,

The sun, from which all excellencies start

In a round nimbus, nor a broken dart

Of moonlight, even, splintered on the sea;

I shall remember only of this hour—

And weep somewhat, as now you see me weep—

The pathos of your love, that, like a flower,

Fearful of death yet amorous of sleep,

Droops for a moment and beholds, dismayed,

The wind whereon its petals shall be laid.

II

What’s this of death, from you who never will die?

Think you the wrist that fashioned you in clay,

The thumb that set the hollow just that way

In your full throat and lidded the long eye

So roundly from the forehead, will let lie

Broken, forgotten, under foot some day

Your unimpeachable body, and so slay

The work he most had been remembered by?

I tell you this: whatever of dust to dust

Goes down, whatever of ashes may return

To its essential self in its own season,

Loveliness such as yours will not be lost,

But, cast in bronze upon his very urn,

Make known him Master, and for what good reason.

III

I know I am but summer to your heart,

And not the full four seasons of the year;

And you must welcome from another part

Such noble moods as are not mine, my dear.

No gracious weight of golden fruits to sell

Have I, nor any wise and wintry thing;

And I have loved you all too long and well

To carry still the high sweet breast of spring.

Wherefore I say: O love, as summer goes,

I must be gone, steal forth with silent drums,

That you may hail anew the bird and rose

When I come back to you, as summer comes.

Else will you seek, at some not distant time,

Even your summer in another clime.

IV

Here is a wound that never will heal, I know,

Being wrought not of a dearness and a death

But of a love turned ashes and the breath

Gone out of beauty; never again will grow

The grass on that scarred acre, though I sow

Young seed there yearly and the sky bequeath

Its friendly weathers down, far underneath

Shall be such bitterness of an old woe.

That April should be shattered by a gust,

That August should be leveled by a rain,

I can endure, and that the lifted dust

Of man should settle to the earth again;

But that a dream can die, will be a thrust

Between my ribs forever of hot pain.

V

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts to-night, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply;

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain,

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone;

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

VI

Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare.

Let all who prate of Beauty hold their peace,

And lay them prone upon the earth and cease

To ponder on themselves, the while they stare

At nothing, intricately drawn nowhere

In shapes of shifting lineage; let geese

Gabble and hiss, but heroes seek release

From dusty bondage into luminous air.

O blinding hour, O holy, terrible day,

When first the shaft into his vision shone

Of light anatomized! Euclid alone

Has looked on Beauty bare. Fortunate they

Who, though once only and then but far away,

Have heard her massive sandal set on stone.

VII

Oh, oh, you will be sorry for that word!

Give back my book and take my kiss instead.

Was it my enemy or my friend I heard?—

“What a big book for such a little head!”

Come, I will show you now my newest hat,

And you may watch me purse my mouth and prink.

Oh, I shall love you still and all of that.

I never again shall tell you what I think.

I shall be sweet and crafty, soft and sly;

You will not catch me reading any more;

I shall be called a wife to pattern by;

And some day when you knock and push the door,

Some sane day, not too bright and not too stormy,

I shall be gone, and you may whistle for me.

VIII

Say what you will, and scratch my heart to find

The roots of last year’s roses in my breast;

I am as surely riper in my mind

As if the fruit stood in the stalls confessed.

Laugh at the unshed leaf, say what you will,

Call me in all things what I was before,

A flutterer in the wind, a woman still;

I tell you I am what I was and more.

My branches weigh me down, frost cleans the air,

My sky is black with small birds bearing south;

Say what you will, confuse me with fine care,

Put by my word as but an April truth,—

Autumn is no less on me that a rose

Hugs the brown bough and sighs before it goes.

Love is Not All

Ballad of the Harpweaver

Attributions

- “Edna St. Vincent Millay“ from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

- Poems in the Public Domain.

May Swenson (1913-1989)

Anna Thilda May “May” Swenson was an American poet and playwright. Harold Bloom considered her one of the most important and original poets of the 20th century.

The first child of Margaret and Dan Arthur Swenson, she grew up as the eldest of 10 children in a Mormon household where Swedish was spoken regularly and English was a second language. Although her conservative family struggled to accept the fact that she was a lesbian, they remained close throughout her life. Much of her later poetry works were devoted to children (e.g. the collection Iconographs, 1970). She also translated the work of contemporary Swedish poets, including the selected poems of Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer.

“Pigeon Woman “

Still Turning

Attributions:

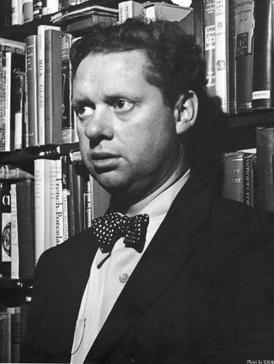

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953)

Dylan Marlais Thomas was an Anglo-Welsh poet who is widely considered one of the most influential English-language poets of the twentieth-century. Although Thomas wrote during the heyday of Modernism, his poetry was radically different from anything produced by the Modernists. Writing deeply personal works fueled by his own troubled emotional life, Thomas produced verse in a highly idiosyncratic style, choosing words often for sound rather than sense and using innovative meters and rhyme schemes similar to those found in the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, whom Thomas greatly admired. Along with Yeats, Thomas’ sonorous and personal style of poetry tinged with his own knowledge of Welsh language and folklore helped to precipitate the Celtic Revival in British literature. Often considered to be one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century in terms of the sheer beauty of his language, Thomas’ influence extends to the present among poets like Seamus Heaney, who attempts to capture the music of ancient poetry in the vocabulary of the present-day.

“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night“

Listen to Thomas reciting his poem:

Attributions:

- “Dylan Thomas” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Walt Whitman is considered to be one of the most influential and significant 19th century American authors. He was born on Long Island in 1819 and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, receiving a limited education. His family was poor and he had to stop going to school when he was eleven to help earn money for his large family of nine children of which he was the second oldest. Because of this, Walt was largely self taught. One of Whitman’s first jobs was working as an apprentice for a Long Island newspaper called the Patriot. This is where he was introduced to the printing press and typesetting. From there, he worked various jobs such as a printer, school teacher, reporter, and editor across the country.

Eventually he settled into writing poetry and self-published his work Leaves of Grass, which was inspired by his travels across America and his admiration for Ralph Waldo Emerson and his writing. While there were countless poets before him, and possibly even more after, Whitman stands alone in his own category when it comes to establishing a place in American literature. His unique ideals and way of commanding the words of his poems has a certain rough elegance that is rare among poets, let alone other poets of his time. His fearlessness when it came to expressing certain more “taboo” themes (such as sex) gives his writing an unmistakable and unmatchable edge, pushing him through the decades to persevere as one of America’s most talented and unique poets.

O Captain! My Captain!

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills,

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding,

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning;

Here Captain! dear father!

This arm beneath your head!

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will,

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done,

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

I Hear American Singing

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear;

Those of mechanics – each one singing his, as it should be, blithe and strong;

The carpenter singing his, as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his, as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work;

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat – the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck;

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench – the hatter singing as he stands;

The wood-cutter’s song – the ploughboy’s, on his way in the morning, or at the noon intermission, or at sundown;

The delicious singing of the mother – or of the young wife at work – or of the girl sewing or washing – Each singing what belongs to her, and to none else;

The day what belongs to the day – At night, the party of young fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing, with open mouths, their strong melodious songs.

A Noiseless Patient Spider

A noiseless, patient spider,

I mark’d, where, on a little promontory, it stood, isolated;

Mark’d how, to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself;

Ever unreeling them–ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you, O my Soul, where you stand,

Surrounded, surrounded, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing,–seeking the spheres, to

connect them;

Till the bridge you will need, be form’d–till the ductile anchor

hold;

Till the gossamer thread you fling, catch somewhere, O my Soul.

Attributions:

- Poetry in the Public Domain

- “Walt Whitman” in Open Anthology of Early American Literature” licensed CC BY 4.0.