3

Learning Objectives

- Identify the key geographic features of Russia

- Analyze how the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union approached the issue of ethnic identity

- Describe the current areas of ethnic conflict within Russia

- Explain how Russian history impacted its modern-day geographic landscape

3.1 Russia’s Physical Geography and Climate

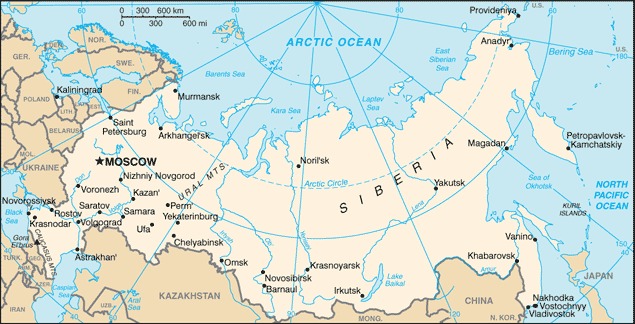

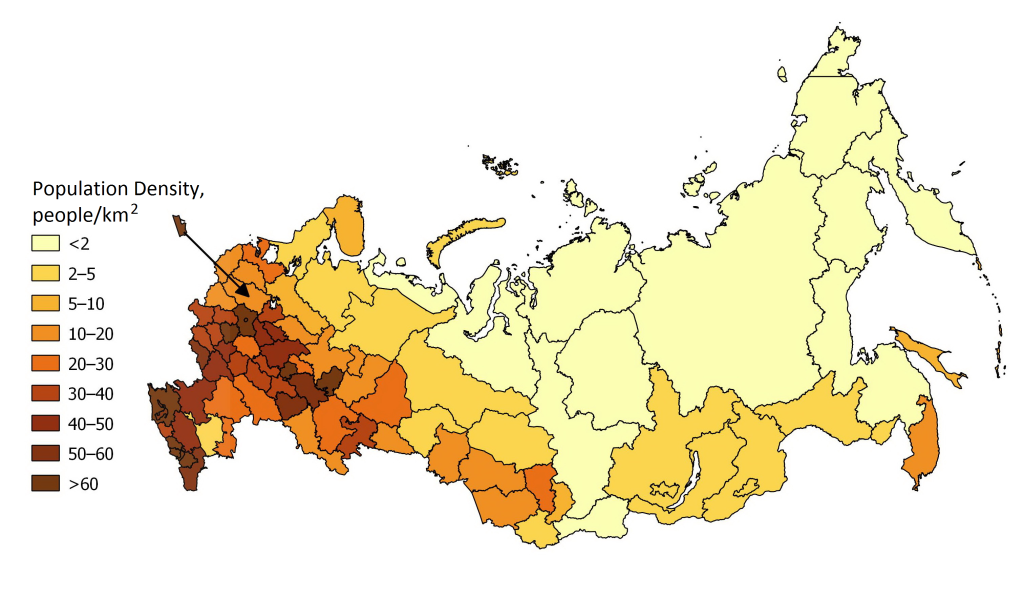

Russia is the largest country in the world, containing 1/8 of the entire world’s land area (see Figure 3.1). Russia is also the northernmost large and populous country in the world, with much of the country lying above the Arctic Circle. Its population, however, is comparatively small with around 143 million people, the majority of whom live south of the 60 degree latitude line and in the western portions of Russia near Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Russia stretches across eleven time zones, spanning 6,000 miles from Saint Petersburg on the Baltic Sea to Vladivostok on the Pacific Coast. The country also includes the exclave, or discontinuous piece of territory, of Kaliningrad situated between Poland and Lithuania.

Because of its large size, Russia has a wide variety of natural features and resources. The country is located on the northeastern portion of the Eurasian landmass. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Pacific Ocean, and to the south, by the Black and Caspian Seas. The Ural Mountains, running north to south, traditionally form the boundary between Europe and Asia and presented a formidable historical barrier to development. Culturally and physiographically, Western Russia, beyond the Ural Mountains, is quite similar to that of Eastern Europe. The region of Russia east of the Ural Mountains is known as Siberia.

In addition to the Ural Mountains, Russia contains several other areas of high relief (see Figure 3.2). Most notably, the Caucasus Mountains, forming the border between Russia and Southwest Asia, and the volcanic highlands of Russia’s far east Kamchatka Peninsula. The western half of Russia is generally more mountainous than the eastern half, which is mostly low-elevation plains.

Russia’s Volga River, running through central Russia into the Caspian Sea, is the longest river on the European continent and drains most of western Russia. The river is also an important source of irrigation and hydroelectric power. Lake Baikal, located in southern Siberia, is the world’s deepest lake and also the world’s largest freshwater lake. It contains around one-fifth of the entire world’s unfrozen surface water. Like the deep lakes of Africa’s rift valley, Lake Baikal was formed from a divergent tectonic plate boundary.

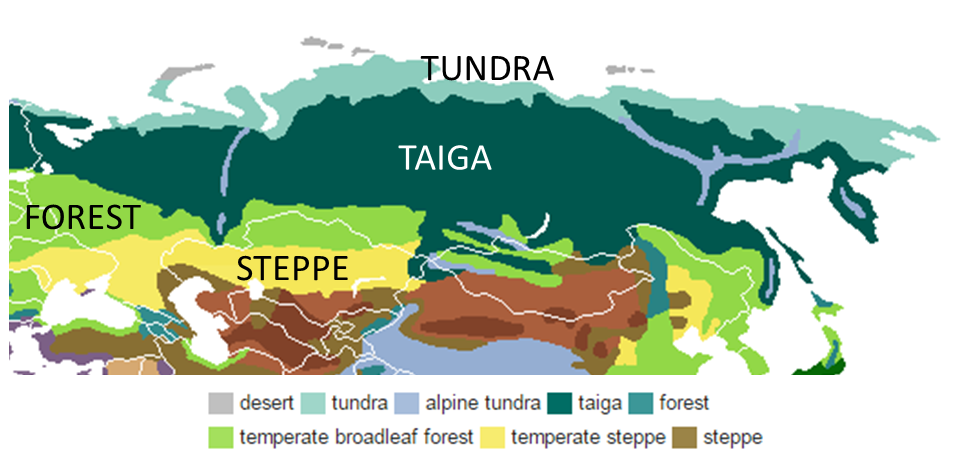

Although Russia’s land area is quite large, much of the region is too cold for agriculture. As shown in Figure 3.3, the northernmost portion of Russia is dominated by tundra, a biome characterized by very cold temperatures and limited tree growth. Here, temperatures can drop below -50°C (-58°F) and much of the soil is permafrost, soil that is consistently below the freezing point of water (0°C or 32°F). South of the tundra is the taiga region, where coniferous, snow-capped forests dominate. This area of Russia contains the world’s largest wood resources, though logging in the region has diminished the supply. South of the taiga region are areas of temperate broadleaf forests and steppe, an area of treeless, grassland plains.

Although looking at a map, you might assume that Russia has extensive port facilities owing to its vast eastern coastline, it actually has relatively few ice-free ports. Vladivostok, located in the extreme southeastern tip of Russia, is its largest port on the Pacific Ocean (see Figure 3.4). Much of the rest of Russia’s Far East region is ice-covered throughout the year, making maritime and automotive transport difficult. In fact, this region was only connected to the rest of Russia by highway for the first time in 2010.

Russia’s climate more broadly is affected by a number of key factors. In terms of its latitudinal position, meaning its position relative to the equator, Russia is located very far north. In general, as you increase in latitude away from the equator, the climate gets colder. The strong east-west alignment of Russia’s major biomes reflects this latitudinal influence. Russia’s climate is also affected by its continental position. In general, areas that exhibit a continental climate are located near the center of a continent away from water bodies and experience more extremes in temperature due to drier air. Water helps regulate air temperature and can absorb temperature changes better than land. In the winter, areas away from water can be very cold, while in the summer, temperatures are quite hot and there is little precipitation. The third key driver of climate in Russia is its altitudinal position. As you increase in elevation, temperatures decrease. You might have experienced this when hiking in mountains or flying on an aircraft and feeling the cold window. Russia’s Ural Mountains, for example, are clearly visible on a map of its biomes as the alpine tundra region owing to its high altitude.

3.2 Settlement and Development Challenges

Russia’s size and varied physiographic regions have presented some challenges for its population. Much of Russia is simply too cold for widespread human settlement. Thus, even though Russia is the largest country, the area that is suitable for agriculture and intensive development is much smaller. In Russia’s northern regions, agricultural development is restricted by short growing seasons and frequent droughts. As snow melts, it takes topsoil with it, and thus erosion is a serious issue in these areas as well.

Still, some have carved out settlements in this frigid environment. Oymyakon, located in northeastern Russia, is considered to be the coldest permanently inhabited places in the world (see Figure 3.5). It has a population of around 500 and temperatures here once dropped to -71.2°C (-96°F)! It takes 20 hours to reach Oymyakon from the nearest city of Yakutsk.

Industry, too, is hampered by Russia’s cold climate in the Siberian region. Although Siberia accounts for over three-quarters of Russia’s land area, it contains only one-quarter of its population. In a region so sparsely populated, how do you build roads, factories, and large settlements? Even if there are resources present, as there are, how do you get them to nearby industrial areas? The industrial developments and human settlements that do exist in this region require high energy consumption and highly specialized facilities needed to cope with cold temperatures and permanently frozen soil.

However, global changes in climate have had some dramatic effects on Russian geography. Areas that were previously permafrost have begun to thaw, leading to erosion and mud, which both present challenges for development. In Siberia, giant holes in the ground began to appear around 2014 and initially baffled scientists. These massive holes were later found to be pockets of methane gas trapped in previously frozen soil that had thawed due to the warming climate. If global temperatures continue to climb, the area of permafrost will shrink, increasing the potential for agriculture in northern Russia. New oil and gas reserves that were previously trapped under frozen soil could likewise become available. Previous shipping routes along Russia’s eastern and northern coasts that were covered in ice could become passable.

While warming temperatures might seem beneficial for Russia’s frigid northern region, they are accompanied by more troublesome long-term concerns. It is estimated that a huge amount of carbon, around 1600 gigatons (or 1.6 trillion tons), is stored in the world’s permafrost. The methane and carbon released from these permafrost stores could exacerbate global warming. Changing temperatures have also been associated with the increased risk of wildfires. In Russia, peatlands, areas of partially decayed vegetation, are particularly at risk. There has been an increase in droughts and flooding throughout Russia and many scientists believe that Russia’s close proximity to the Arctic Circle makes it even more vulnerable to changes in temperature.

Climate factors have also shaped the distribution of Russia’s population. Most of Russia’s population lives west of the Ural Mountains where the climate is more temperate and there are more connections with Eastern Europe (see Figure 3.6). Russia is highly urbanized, with almost three-quarters of the population living in cities. Its largest city and capital, Moscow, is home to around 12 million people.

Russia’s population has experienced some interesting changes over the past few decades. Its population peaked at over 148 million in the early 1990s before experiencing a rapid decline. When geographers explore a country’s population, they don’t just ask “Where is it changing?” but also “Why is it changing?” For Russia, the economic declines coinciding with the dissolution of the Soviet Union contributed to low birth rates. Generally, when a country experiences economic decline or uncertainty, people tend to delay having children. Today, due to higher birth rates and a government push to encourage immigration, Russia’s population growth has stabilized and could grow from 143.5 million in 2013 to 146 million by 2050. Russia’s death rate remains quite high, however, at 13.1 per 1000 people compared to the European Union average of 9.7 per 1000. Alcoholism rates are high, particularly among men in Russia, and cardiovascular disease accounts for over half of all deaths. In addition, although Russia is highly urbanized, more people are now moving from Russia’s crowded cities to more sparsely populated rural areas, in contrast to the more common rural to urban migration seen elsewhere in the world.

3.3 Russian History and Expansion

Russia’s current geographic landscape has been shaped by physical features, such as climate and topography, as well as historical events. Why is the capital of Russia Moscow, and why is its population so clustered in the west? In the 13th century, Moscow was actually an important principality, or city-state ruled by a monarch. The Grand Duchy of Moscow, or Muscovy as it was known in English, became a powerful state, defeating and surrounding its neighbors and claiming control over a large portion of Rus’ territory, an ancient region occupied by a number of East Slavic tribes. The Slavs represent the largest Indo-European ethno-linguistic group in Europe and include Poles, Ukrainians, Serbs, as well as Russians.

From the mid-1400s onward, the Muscovite territory expanded at an impressive rate (see Figure 3.7). In 1300 CE, the territory occupied an area of around 20,000 square kilometers; by 1462 CE, that number increased to 430,000 square kilometers. By 1584 CE, the territory had swelled to 5.4 million square kilometers.

During this time, Russia’s government shifted as well. In 1547 CE, Grand Duke Ivan IV, better known as “Ivan the Terrible,” crowned himself the first Tsar. The term tsar, also spelled czar, stems from the Roman title “Caesar” and was used to designate a ruler, much like the term “king” or “emperor.” Ivan IV nearly doubled the territory of Russia during his reign, conquering numerous surrounding ethnic groups and tribes.

Russia’s status as an “empire” dates back to the 1700s under the rule of Peter the Great. Peter was able to conquer Russia’s northwestern regions, establishing eastern seaports and founding the forward capital of Saint Petersburg along the Baltic Sea. A forward capital is a capital that has been intentionally relocated, generally because of economic or strategic reasons, and is often positioned on the edge of contested territory. Overall, the reforms of Peter the Great transformed the country and made it more similar to Western Europe.

The conclusion of World War I coincided with the end of the Russian Empire. The Russian Army fared poorly in the war, with approximately 1.7 million casualties. Russia’s people felt that the ruling class had become detached from the problems of everyday people and there were widespread rumors of corruption. Russia went through a rapid period of industrialization, which left many traditional farmers out of work. As people moved to the cities, there was inadequate housing and insufficient jobs. The economic and human cost of World War I, coupled with the plight of workers who felt exploited during the Industrial Revolution, ultimately led to the overthrow of Nicholas II who, along with his family, was imprisoned and later executed.

Eventually, the Bolsheviks, a Marxist political party led by Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the interim government and created the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, abbreviated as the USSR and sometimes simply called the Soviet Union. The capital was also moved back to Moscow from Saint Petersburg. After Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin took control and instituted both a socialist economy and collective agriculture. Ideally, the changes the Bolsheviks supported were intended to address the failures of Nicholas II providing more stable wages and food supplies. Rather than have individual peasant farms that had limited interconnections and poor systems of distribution, the state would collectivize farming with several farming families collectively owning the land. Under a command economy, the production, prices of goods, and wages received by workers is set by the government. In the Soviet Union, the government took control of all industries and invested heavily in the production of capital goods, those that are used to produce other goods, such as machinery and tools. Though this system was intended to address concerns and inequalities that had developed under the tsars, the Soviet government under Stalin was fraught with its own economic and social problems.

3.4 Russian Multiculturalism and Tension

During the period of Russia’s expansion and development as an empire, and later during the time of the Soviet Union, Russia’s territory included not only ethnic Russians but other surrounding groups as well. Ethnicity is a key feature of cultural identity and refers to the identification of a group of people with a common language, ancestry, or cultural history. Many of these minority ethnic groups harbored resentment over being controlled by an imperial power.

Prior to the Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian Empire’s response to the non-Russian communities they controlled was known as Russification, where non-Russian groups give up their ethnic and linguistic identity and adopt the Russian culture and language. This type of policy is known as cultural assimilation, where one cultural group adopts the language and customs of another group. The Russian language was taught in schools and minority languages were banned in public places. Catholic schools were banned and instead, Russian Orthodoxy, part of the Eastern Orthodox Church, was taught at state-run schools. The Russian Empire essentially sought to make everyone in the territory Russian. This policy was only marginally successful, however, and was especially difficult to implement in the outer regions.

Under the Soviet Union, the policy of cultural assimilation had less to do with becoming Russian and more to do with being part of the Soviet Union, what could be thought of as Sovietization. The Soviet government organized the country as a federation, where territories within the country had varying degrees of autonomy (see Figure 3.8). The larger ethnic groups formed the Soviet Socialist Republics, or SSRs. The Uzbek SSR, for example, largely contained members of the Uzbek ethnic group. The Kazakh SSR similarly consisted mostly of people who were ethnically Kazakh. These SSRs did not represent all of the ethnic diversity present in Russia nor did they provide these territories with autonomy. You might recognize the names of these republics as they gradually became independent states after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Turkmen SSR became Turkmenistan, for example. Many of these areas, particularly in Central Asia, are majority Muslim and thus adopted the Persian suffix “-stan” meaning “place of” or “country” after independence.

Under Soviet Rule, some policies of Russification expanded. In Muslim areas of Central Asia and the Caucasus, the use of the Arabic alphabet, the language of the Qur’an, was abolished. The government also sent many Russians into majority non-Russian areas to further unify the country. Other ethnic groups, particularly those perceived as troublemakers by the government, were deported from their ancestral homelands and resettled elsewhere. The ethnic map of the former Soviet Union today, in part, reflects this multicultural history and the legacy of resettlement policies (see Figure 3.9). Over 3 million people were deported to Siberia between 1941 and 1949, a large portion of whom died from disease or malnutrition. Others were deported from the Baltic area or from the area near the Black Sea. Overall, around 6 million people were internally displaced as a result of the Soviet Union’s resettlement policies and between 1 and 1.5 million of them died as a result.

Although Russia today is comprised mostly of people who speak Russian and identify with the Russian ethnicity, it contains 185 different ethnic groups speaking over 100 different languages. The largest minority groups in Russia are the Tatars, representing around 4 percent of the population with over 5 million people, and Ukrainians at around 1.4 percent or almost 2 million people. Other ethnic groups, like the Votes near Saint Petersburg, have only a few dozen members remaining. Because of the Soviet resettlement policies, the former Soviet republics have sizable Russian minorities. Kazakhstan and Latvia, for example, are almost one-quarter Russian. This has often led to tension within Russia as minority groups have sought independence and outside of Russia as ethnic groups have clashed over leadership.

In Ukraine in particular, tension between the Ukrainian population and Russian minority has remained high and represents a broader tension between the Eastern European regions that are more closely aligned with Russia and those that seek greater connectivity and trade with Western Europe. Eastern Ukraine is largely comprised of Russian speakers, whileWestern Ukraine predominantly speaks the state language of Ukrainian (see Figure 3.10). Overall, around three-quarters of people in Ukraine identify with the Ukrainian ethnicity.

In 2014, the tension between the two groups escalated as then-president Victor Yanukovych backed away from a deal to increase connections with the European Union and instead sought closer ties with Russia. In Western Ukraine, people engaged in widespread protests prompting the government to sign a set of anti-protest laws, while in Eastern Ukraine, most supported the government. Ultimately, Yanukovych was removed from office prompting military intervention from Russia.

Specifically, Russia sought control of Crimea, an area that had been annexed by the Russian Empire and was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic until the 1950s when it was transferred to Ukraine. After the 2014 protests, a majority of the people of Crimea supported joining Russia and it was formally annexed by Russian forces. The region is now controlled by Russia (see Figure 3.11). The international community, however, has largely not recognized Crimea’s sovereignty or Russia’s annexation. This conflict again escalated in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine, leading to the largest European refugee crisis since World War II.

Commons)

Several other ethnic groups that remain in Russia desire independence, particularly in the outskirts of the country in the Caucasus region along Russia’s border with Georgia and Armenia (see Figure 3.12). Chechnya is largely comprised of Chechens, a distinct Sunni Muslim nation. The territory opposed Russian conquest of the region in the 19th century but was forcefully incorporated into the Soviet Union in the early 20th century. 400,000 Chechens were deported by Stalin in the 1940s and more than 100,000 died. Although Chechnya sought independence from Russia, sometimes through violent opposition, it has remained under Russian control following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Dagestan has been the site of several Islamic insurgencies seeking separation from Russia. Ossetia remains divided between a northern portion controlled by Russia and a southern region controlled by Georgia.

In an area as large and as ethnically diverse as Russia, controlling the territory in a way that is acceptable to all of its residents has proven difficult. In many large countries, the farther away you get from the capital area and large cities, the more cultural differences you find. Some governments have embraced this cultural difference, creating autonomous regions that function largely independently though remain part of the larger state. Stalin and Russia’s tsars before him tried to unify the country through the suppression of ethnic difference, but ethnic and linguistic identities are difficult to obliterate.

3.5 Economics and Development in the Soviet Union

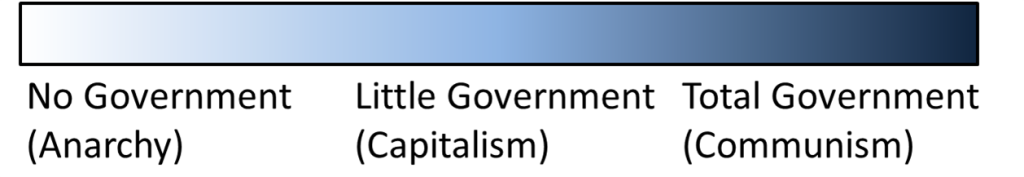

The Soviet Government, led by Lenin and later by Stalin, advocated a communist system. In a capitalist system, market forces dictate prices according to supply and demand. Those who control the means of production, known as the bourgeoisie in the Marxist philosophy, are much wealthier than the workers, known as the proletariat. In a communist system, however, the means of production are communally owned, and the intended result is that there are no classes of rich and poor and no groups of landowners and landless workers.

In reality, no government practices pure capitalism or pure communism, but rather, governments are situated along a continuum (see Figure 3.13). Anarchy, the absence of government control, exists only in temporary situations, such as when a previous government is overthrown and political groups are vying for power. In most Western countries, a mix of capitalism and socialism, where economic and social systems are communally owned, is practiced to varying degrees. Denmark, for example, which has been consistently ranked as one of the happiest countries in the world, has a market economy with few business regulations but government funded universal healthcare, unemployment compensation, and maternity leave, and most higher education is free. The United States is largely capitalist, but the government provides retirement benefits through the social security system, funds the military, and supports the building and maintenance of the interstate highway system. Although China’s government is communist, it has also embraced elements of the market economy and allows some private enterprise as well as foreign trade and investment. All governments must address three basic questions of economics: what to produce, how to produce, and for whom to produce. The answers to these questions vary depending on the state and the situation.

In the Soviet system, the government dictated economic policy, rather than relying on free market mechanisms and the law of supply and demand. This required the government to intervene at all levels of the economy. The prices of goods needed to be set by the central government, the production levels of goods needed to be determined, the coordination of manufacturers and distributors was needed – everything that is traditionally accomplished through private individuals and companies in a capitalist model was the responsibility of the Soviet government.

To coordinate such a wide array of goods and services, long-term planning was needed. The Soviet government instituted a series of five-year plans which established long-term goals and emphasized quotas for the production of goods. This system lacked flexibility, however, and was often inefficient in its production and distribution of goods.

The Soviet government had two principle objectives: first, to accelerate industrialization, and secondly, to collectivize agriculture. The collectivization of agriculture, though intended to increase crop yields and make distribution of food more efficient, was ultimately a failure. By the early 1930s, 90 percent of agricultural land in the Soviet Union had become collectivized, meaning owned by a collection of people rather than individuals. Every element of the production of agriculture, from the tractors to the livestock, was collectivized rather than individually owned. A family could not even have its own vegetable garden. Ideally, under such a system, all farmers would work equally and would share the benefits equally.

Unfortunately, the earnings of collective farmers was typically less than private farmers. This led to a reduction in agricultural output as well as a reduction in the number of livestock. Coupled with a poor harvest in the early 1930s, the country experienced widespread famine and food insecurity. It is estimated that 12 million people died as a result of the collectivization of agriculture.

Soviet industrial development, too, was plagued with inefficiencies. In a typical market economy, particular places specialize in the production of certain goods and the system works out the most efficient method of production and distribution. A furniture maker might locate near a supply of hardwood, for example, to minimize transportation costs. A large factory might locate near a hydroelectric plant to ensure an inexpensive power source. Certain places, due to luck or physical geography, have more resources than others and this can lead to regional imbalances. The Soviet government, however, wanted everything and everyone to be equal. If one region had all of the industrial development, then the people in that region would be disproportionately wealthy and the region would be more vulnerable to attack by an outside force. The government also hoped that the dispersal of industry would force the country to be interconnected. If one area had a steel plant and another had a factory that used steel to produce machines, the two would have to rely on one another and neither would have an advantage. Thus, they aimed to disperse industrial development across the country.

If you were a geographer tasked with finding the best location for a new industry, you’d likely take into account underlying resources, such as the raw materials needed for manufacturing and the energy needed to power the factory. You might think about labor supplies and try to locate the industry near a large labor pool. You might also think about how to get the good to consumers efficiently, and locate near a shipping port or rail line. Rather than take these geographic factors into account, however, the Soviet government sought to disperse industry as much as possible. Industries were located with little regard for the location of labor or raw materials. This meant that inefficiencies were built into the system, and unnecessary transportation costs

mounted.

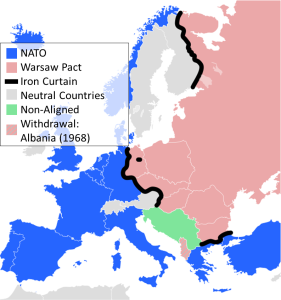

The substantial costs of supporting an inefficient system of industrial development were magnified by the costs needed to fund the Cold War. The Cold War occurred following World War II and was a time of political and military tension primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union. Western Europe, which was largely capitalist, was divided from the communist Soviet Union by the so-called Iron Curtain, a dividing line between the Soviet Union and its satellite states who aligned with the Warsaw Pact, a collective defense treaty, and Western European countries allied through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (see Figure 3.14). The Cold War was so named because it was different from a traditional “hot” war in that it did not involve direct military conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. It did, however, result in armed conflicts in other parts of the world as well as a massive stockpile of military weaponry.

During the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev supported restructuring the Soviet economy with a series of some market-like reforms, known as Perestroika. He also supported glasnost, an increase in government transparency and openness. Unfortunately, these reforms could not change the system quickly enough and loosened government controls only worsened the condition and inefficiencies of the Soviet economy.

The Soviet government, already stretched thin financially from a system of development that largely ignored geography, could not support the unprofitable state-supported enterprises and mounting military expenses. Ultimately, the country went bankrupt. In a system where every aspect of the economy is linked, it only takes one link to break the chain and far-from Gorbachev’s policies strengthening the chain, Perestroika only weakened it further. The Soviet Union formally dissolved in 1991. Some have argued that the Soviet Union collapsed economically. Others maintain that it was primarily a political collapse, led by an ineffective government and increasing territorial resistance. Geography largely played a role as well, with the government ignoring fundamental principles of spatial location and interaction.

3.6 The Modern Russian Landscape

The collapse of the Soviet Union had far-reaching effects on the Russian landscape and even today, Russia is affected by the legacy of the Soviet Union. The remnants of Soviet bureaucracy, for example, affect everything from the cost of road building to the forms needed to get clothes dry cleaned. After the immediate collapse of the Soviet Union, the government transitioned to a market economy. In many cases, those who had positions of power within the Soviet government gained control over previously state-owned industries creating a wealthy class often called a Russian oligarchy. Despite some setbacks and global economic downturns, Russia’s economy has improved significantly since the end of the Soviet Union and Russia now has the sixth-largest economy in the world. Poverty and unemployment rates have also fallen sharply in recent decades. Although Russia’s population fell sharply following the Soviet Union’s collapse, it has rebounded somewhat in recent years.

Abandoned industrial towns and work settlements built by the Soviet Union dot the landscape, evidence of the Soviet government’s ill-fated attempt to decentralize its population and development (see Figure 3.15). The Trans-Siberian Railway, completed in 1916 to connect Moscow with Russia’s eastern reaches in Vladivostok, continues to be the most important transportation link in Russia, but Russia’s highway system remains largely centralized in the west. In the east, the decentralization of settlements and difficult physical conditions has made building and maintaining road networks difficult. The Lena Highway, for example, nicknamed the “Highway from Hell,” is a federal highway running 1,235 km (767 mi) north to south in eastern Siberia. It was just a dirt road until 2014, often turning into an impassible, muddy swamp in summer.

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia’s 2nd and 4th president, Russia’s economy has grown consistently, aided by high oil prices and global oil demand. Putin also instituted police and military reforms, and persecuted some of the wealthy oligarchs who had taken control of private enterprises. Critics also note that Putin has enacted a number of laws seeking to quiet political dissent and personal freedoms. There have been numerous documented cases of the torture of prisoners and members of the armed forces as well as a number of suspicious killings of journalists and lawmakers.

Although the Cold War officially ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union, tension between Russia and the West remains high. Military conflict in the former Soviet states, like Ukraine, has often reignited simmering hostilities. Still, there is some evidence of cooperation. In 2015, Putin told fellow world leaders that climate change was “one of the gravest challenges humanity is facing” and backed the United Nation’s climate change agreement. Previously, Putin had stated that for a country as cold as Russia, global warming would simply mean that Russians would have to buy fewer fur coats. The U.S. and Russian space agencies also continue to work together, announcing plans to cooperatively build a new space station.

a biome characterized by very cold temperatures and limited tree growth

soil that is consistently below the freezing point of water (0°C or 32°F)

a biome characterized by cold temperatures and coniferous forests

a biome characterized by treeless, grassland plains

areas near the center of a continent that experience more extremes in temperature due to their location away from bodies of water

an ethno-linguistic group located in Central and Eastern Europe that includes West Slavs (such as Poles, Czechs, and Slovaks), East Slavs (including Russians and Ukrainians), and South Slavs (namely Serbs, Croats, and others)

a capital that has been intentionally relocated, generally because of economic or strategic regions, and is often positioned on the edge of contested territory

a Marxist political party led by Vladimir Lenin that overthrew the interim government following the Russian Revolution and created the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

an economic system where the production, prices of goods, and wages received by workers is set by the government

the identification of a group of people with a common language, ancestry, or cultural history

a system of cultural assimilation in Russia where non-Russian groups give up their ethnic and linguistic identity and adopt the Russian culture and language

when one cultural group adopts the language and customs of another group

a branch of Christianity that split from Roman Catholicism in 1054 CE and includes a number of different denominations such as the Russian Orthodox and Greek Orthodox churches

a time of political and military tension primarily between the United States and the Soviet Union following World War II and lasting until the early 1990s with the fall of the Soviet Union

an imaginary dividing line between the Soviet Union and its satellite states who aligned with the Warsaw Pact, a collective defense treaty, and Western European countries allied through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

an east-west rail line completed in 1919 that stretches across Russia, connecting Moscow in the west with Vladivosktok in the east