2

Learning Objectives

- Identify the key geographic features of Europe

- Explain how the industrial revolution has shaped the geographic landscape of Europe

- Summarize how migration has impacted Europe’s population

- Describe the current controversies regarding migration to Europe

2.1 European Physical Geography and Boundaries

Europe? Where’s that? It might seem like a relatively easy question to answer, but looking at the map, the boundaries of Europe are harder to define than it might seem. Traditionally, the continent of “Europe” referred to the western extremity of the landmass known as Eurasia (see Figure 2.1). Eurasia is a massive tectonic plate, so determining where exactly Europe ends and Asia begins is difficult. Europe is bordered by the Arctic Ocean in the North, the Atlantic Ocean and its seas to the west, and the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea to the south. Europe’s eastern boundary is typically given as the Ural Mountains, which run north to south from the Arctic Ocean down through Russia to Kazakhstan. The western portion of Russia, containing the cities of St. Petersburg and Moscow, is thus considered part of Europe while the eastern portion is considered part of Asia. Culturally and physiographically, Western Russia is strikingly similar to Eastern Europe. These two regions share a common history as well with Russian influence extending throughout this transition zone.

In addition to the Ural Mountains, Europe has several other mountain ranges, most of which are in the southern portion of the continent. The Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Carpathians divide Europe’s southern Alpine region from the hilly central uplands. Northern Europe is characterized by lowlands and is relatively flat. Europe’s western highlands include the Scandinavian Mountains of Norway and Sweden as well as the Scottish Highlands.

Europe has a large number of navigable waterways, and most places in Europe are relatively short distances from the sea. This has contributed to numerous historical trading links across the region and allowed for Europe to dominate maritime travel. The Danube, sometimes referred to as the “Blue Danube” after a famous Austrian waltz of the same name, is the European region’s largest river and winds its way along 2,860 km (1,780 mi) and 10 countries from Germany to Ukraine.

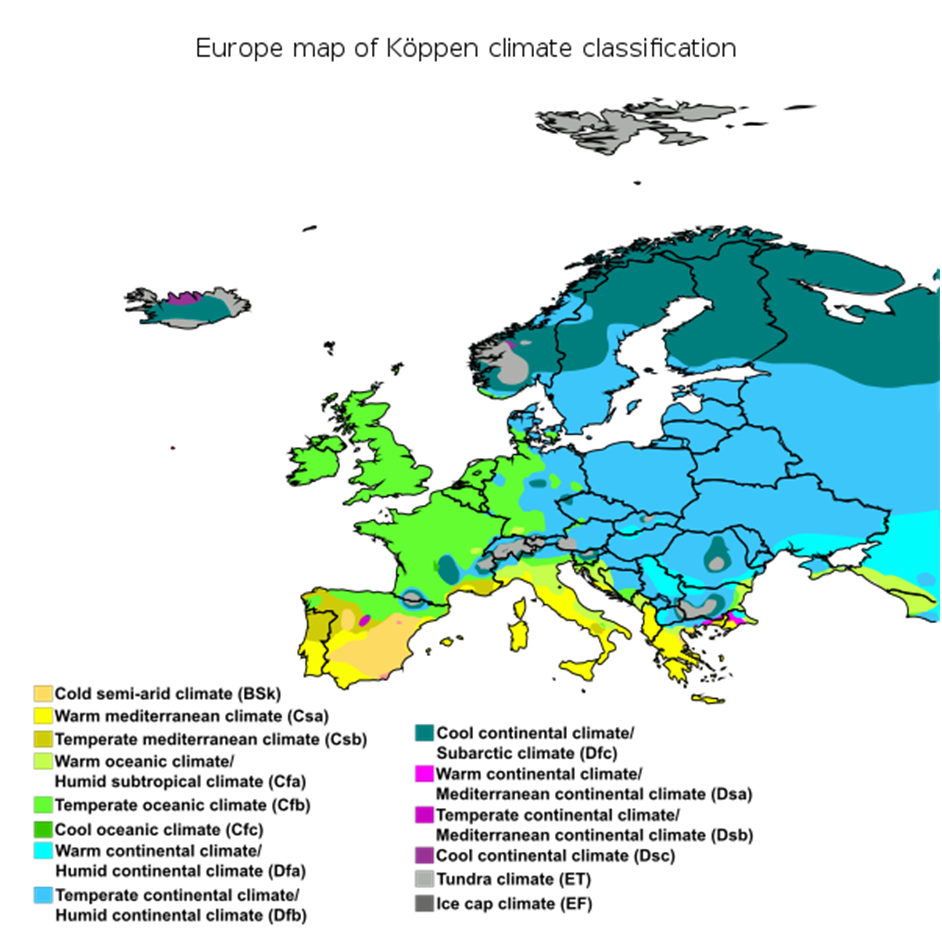

This proximity to water also affects Europe’s climate (see Figure 2.2). While you might imagine much of Europe to be quite cold given its high latitudinal position, the region is surprisingly temperate. The Gulf Stream brings warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean to Europe’s coastal region and warms the winds that blow across the continent. Amsterdam, for example, lies just above the 52°N line of latitude, around the same latitudinal position as Saskatoon, in Canada’s central Saskatchewan province. Yet Amsterdam’s average low in January, its coldest month, is around 0.8°C (33.4°F) while Saskatoon’s average low in January is -20.7°C (-5.3°F)!

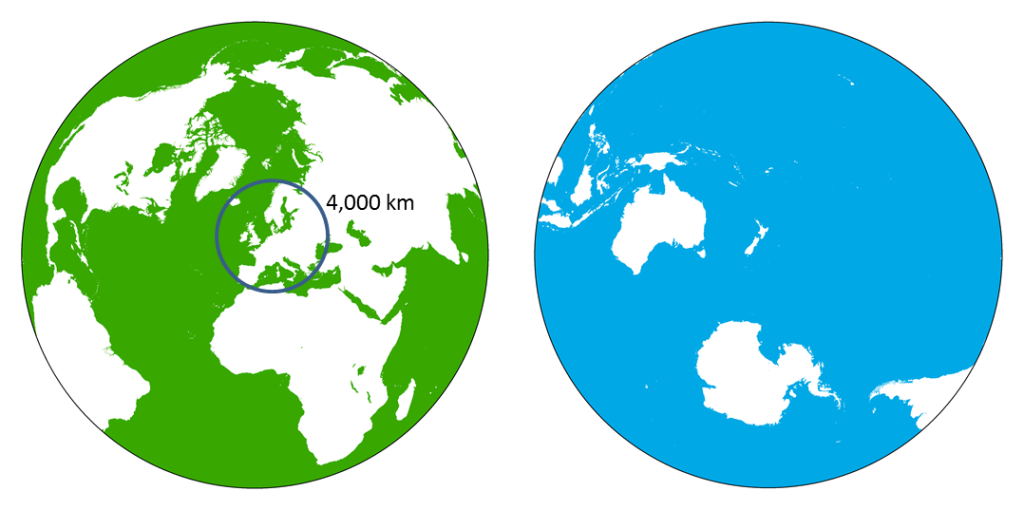

While geographers can discuss Europe’s absolute location and the specific features of its physical environment, we can also consider Europe’s relative location. That is, its location relative to other parts of the world. Europe lies at the heart of what’s known as the land hemisphere. If you tipped a globe on its side and split it so that half of the world had most of the land and half had most of the water, Europe would be at the center of this land hemisphere (see Figure 2.3). This, combined with the presence of numerous navigable waterways, allowed for maximum contact between Europe and the rest of the world. Furthermore, distances between countries in Europe are relatively small. Paris, France, for example, is just over a two-hour high speed rail trip from London, England.

This relative location provided efficient travel times between Europe and the rest of the world, which contributed to Europe’s historical dominance. When we consider globalization, the scale of the world is shrinking as the world’s people are becoming more interconnected. For Europe, however, the region’s peoples have long been interconnected with overlapping histories, physical features, and resources.

2.2 Cooperation and Control in Europe

Europe’s physical landforms, climate, and underlying resources have shaped the distribution of people across the region.When early humans began settling this region, they likely migrated through the Caucasus Mountains of Southwest Asia and across the Bosporus Strait from what is now Turkey into Greece. The Greeks provided much of the cultural and political foundations for modern European society. Greek ideals of democracy, humanism, and rationalism reemerged in Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. The Roman Empire followed the Greek Empire, pushing further into Europe and leaving its own marks on European society (see Figure 2.4). Modern European architecture, governance, and even language can be traced back to the Roman Empire’s influence.

The Roman’s vast European and Southwest Asian empire united the region under Christianity and created new networks of roads and trading ports. With the fall of the Roman Empire, however, tribal and ethnic allegiances reemerged and a number of invasions and migrations occurred. England, for example, was settled by the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, from which the name “England” or “Angeln” is derived, then by the Normans from present-day France.

Europe today is comprised of 40 countries, but historically, this was a region dominated by kingdoms and empires – even fairly recently. A map of Europe from just 200 years ago looks strikingly different from today’s political boundaries (see Figure 2.5) . At that time, Greece and Turkey were still controlled by the Ottoman Empire and Italy was a conglomerate of various city-states and independent kingdoms. Many of the countries and political boundaries of Europe we know today were not formed until after World War II.

Europe’s population has shifted and changed over time as well. Whereas Europe was once largely feudal and agrarian, today around 75 percent of its people live in cities. Europe’s largest city is London, with a population of around 8.5 million within its city limits. Although the United Kingdom was the dominant force in Europe during industrialization, Germany now dominates the region in terms of population, gross domestic product, and size.

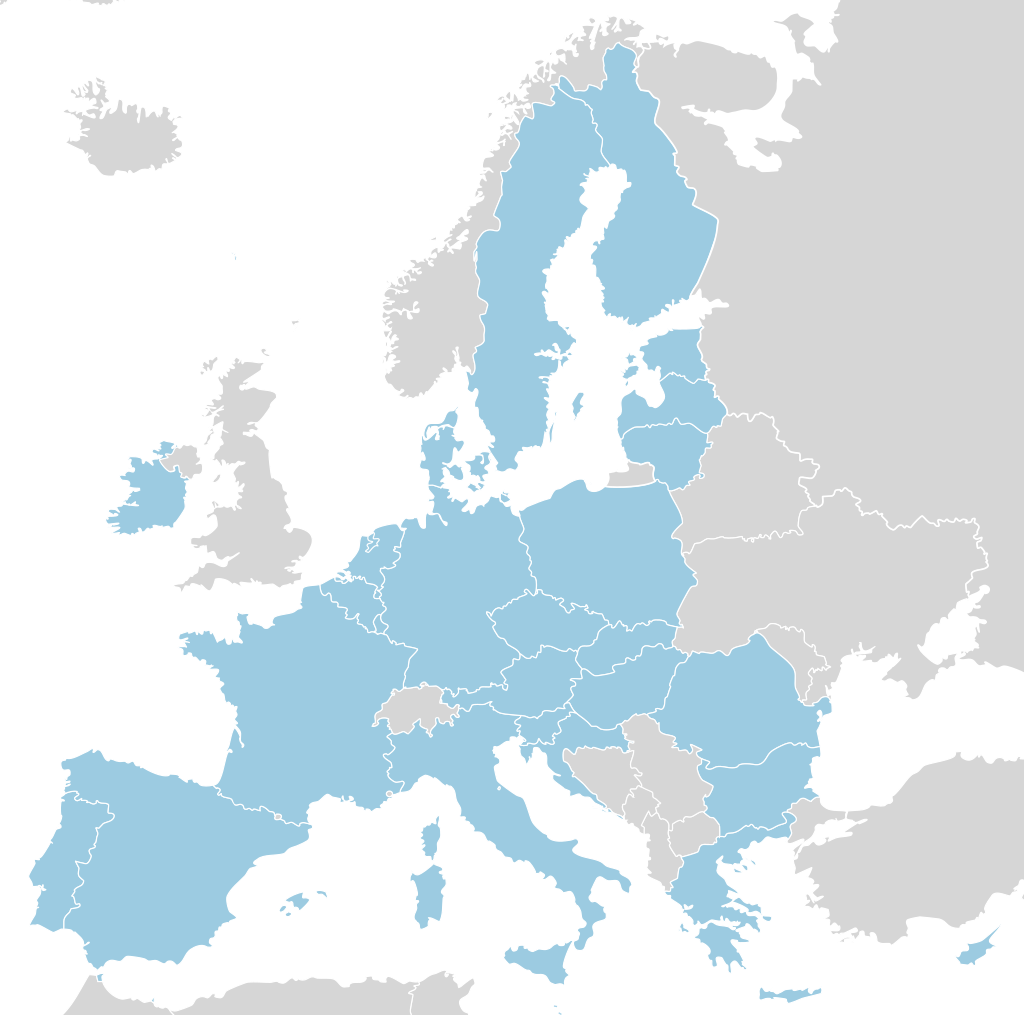

The political map of Europe continues to change, with shifting alliances, competing goals, and new pushes for independence. In general, Western Europe has moved toward cooperation. The European Union developed out of the Benelux Economic Union signed in 1944 between Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. France, Italy, and West Germany signed an economic agreement with the Benelux states in 1957, and from there, the economic cooperation continued to expand. The European Union (EU) itself was created in 1993 and today, the organization has 27 member countries (see Figure 2.6). Not all members of the EU use the euro, its official currency; the 19 member states who do are known as the eurozone. The United Kingdom is the only state to have left the EU. Its withdrawal is known as “Brexit” (meaning “British exit”) and was finalized in January 2020.

Today, it is relatively easy to travel across Europe, in part because of economic and monetary cooperation, but also because internal border checks have largely been abolished. The Schengen Agreement, signed in the 1990s allows member states to essentially function as a single territory in terms of entry. These states share a common visa system and residents and vehicles can travel freely throughout states participating in the agreement.

Although the European Union has provided member states with a number of advantages, the system has had some structural concerns. Greece, for example, admitted to the EU in 1981, adopted the euro in 2001. It has had continued issues with debt, however, and has required massive bailouts from other member states. The United Kingdom held a referendum in June 2016 and decided to leave the EU, the first time a country has made the decision to leave the organization. When analyzing the EU and its advantages and disadvantages, you might consider why a country would join a supranational organization. To join an organization like the EU, a country gives up some of its sovereignty, its independence in making economic, political, or legal decisions. Ideally, a country would gain more than it loses. Countries united economically can more easily facilitate trade, for example, or could share a common military rather than each supporting their own. Those who favored the United Kingdom withdrawing from the EU, however, argued that membership in the EU did not offer enough advantages and preferred the United Kingdom to control its own trade deals and immigration restrictions.

Devolution, which occurs when regions within a state seek greater autonomy, has continued in Europe, representing a tension between nationalistic ideals and ethnic ties. In the United Kingdom, a 2014 Scottish independence referendum was narrowly defeated but led to greater autonomy for Scotland. In general, policies offering increased autonomy have kept the map of Western Europe fairly intact. Ethnic groups seeking sovereignty often want political autonomy but economic integration, and thus devolution generally allows them more decision-making power.

In the Balkan region, however, strong ethnic identities has contributed to continued political instability and the formation of new states. In fact, the devolutionary forces found in this region led to the creation of the term Balkanization, referring to the tendency of territories to break up into smaller, often hostile units. The Balkans came under the control of the Ottoman Empire, and once the empire collapsed following World War I, several territories in this region were joined together as the country of Yugoslavia (see Figure 2.7). Following World War II, Yugoslavia was led by Josip Broz Tito who attempted to unify the region by suppressing ethnic allegiances in favor of national unity. After his death, however, those ethnic tensions reemerged. In the 1990s, Yugoslavia was led by the dictator Slobodan Miloševi´c, a Serbian who supported a genocidal campaign against the region’s Croats, Bosnians, and Albanians. In Bosnia alone, over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were killed. Most recently, Kosovo, comprised mostly of Albanian Muslims, declared independence from Serbia in 2008, though its status as a sovereign state is still contested by some, including Serbia, Bosnia, and Greece.

The map of Europe continues to evolve. In February 2019, for instance, the country formerly known as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia officially changed its name to the Republic of North Macedonia, or just North Macedonia, resolving a long dispute with Greece.

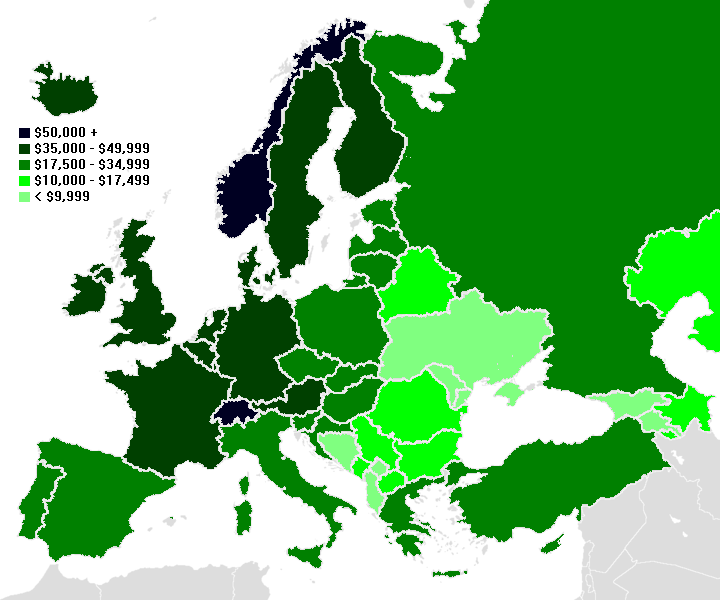

While some countries in the region have decidedly benefitted from globalization, others remain fairly limited in terms of global trade and global economic integration. Figure 2.8, a map of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita reveals a marked difference between the states of Western Europe and the eastern region. Germany’s GDP per capita as of 2017, for example, was $44,470 (in US dollars), according to the World Bank. In Moldova, a former Soviet republic bordering Romania, that figure was $2,290.

2.3 The Industrial Revolution

The differences in levels of development across Europe today have largely been shaped by the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution refers to the changes in manufacturing that occurred in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These changes had profound effects on society, economics, and agriculture, not just in Europe, but globally.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most goods in Europe were produced in the home. These so-called “cottage” industries consisted of individual workers making unique goods in their homes, usually on a part-time basis. These products, such as clothing, candles, or small housewares, could be sold by a farming family to supplement their income.

The Industrial Revolution began in the United Kingdom, and while it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact point at which the revolution began, a key invention was James Watt’s steam engine, which entered production in 1775. This steam-driven engine was adopted by industries to allow for factory production. Machines could now be used instead of human or animal labor. Interestingly, a side effect of the steam engine was that it enabled better iron production, since iron required an even and steady stream of heat. This improved iron was then used to build more efficient steam engines, which in turn produced increasingly better iron. These improvements and new technologies gradually spread across Europe, eventually diffusing to the United States and Japan.

During this time, there were also significant changes in agricultural production. The Agrarian Revolution began in the mid-1750s and was based upon a number of agricultural innovations. This was the Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific reasoning championed during this era was applied to the growing of crops. Farmers began using mechanized equipment, rather than relying solely on human or animal labor. Fertilizers improved soil conditions, and crop rotation and complementary planting further increased crop yields. During this time period, there was a shift to commercial agriculture, where excess crops are sold for a profit, rather than subsistence agriculture, where farmers primarily grow food for their own family’s consumption.

Around the same time improvements in rail transportation changed both the way goods were distributed across Europe and the movement of people across the region. The use of steam engines and improved iron also transformed the shipping industry, with steamships beginning to set sail across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Agrarian Revolution coupled with the Industrial Revolution profoundly changed European geography. With the improvements of the Agrarian Revolution, farmers could produce more with less work. This provided an agricultural surplus, enabling a sustained population increase. Port cities and capital cities became centers of trade and expanded. Critically, the Agrarian Revolution freed workers from having to farm, since fewer farmers were needed to produce the same amount of crops, enabling people to find work in the factories. These factories were primarily located in cities, and thus it was the combination of these two revolutions that dramatically increased urbanization in Europe. At the start of the 19th century, around 17 percent of England’s population lived in cities; by the end of the 19th century, that figure had risen to 54 percent.

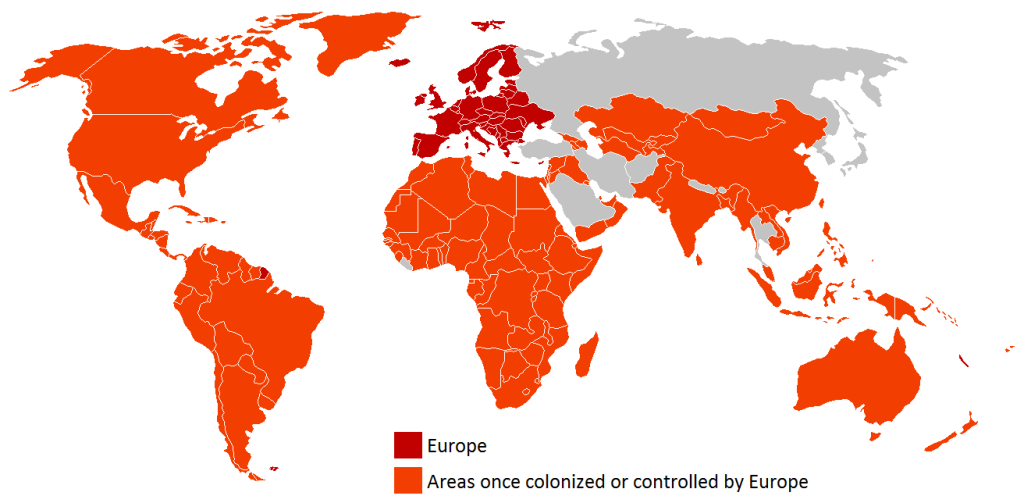

Overall, the Industrial Revolution considerably improved European power by boosting their economies, improving their military technology, and increasing their transportation efficiency. Even before the Industrial Revolution, Europe exerted a considerable amount of control over the rest of the world. European colonialism began in the 1400s, led by Portugal and Spain. In the 1500s, England, France, and the Dutch began their own colonial campaigns. By the start of WorldWar I, the British Empire, boosted by the improvements of the Industrial Revolution, had the largest empire in history, covering 20 percent of the world’s population at the time (see Figure 2.9).

Coinciding with the Industrial and Agrarian Revolutions were a number of political revolutions in Europe. The most influential political change came as the result of the French Revolution, which occurred between 1789 and 1799 CE. This revolution ended France’s monarchy, establishing a republic, and provided the foundation for numerous political revolutions that followed. It also weakened the power of the Roman Catholic Church in France, inspiring the modern-day separation between church and state that is typical of many Western countries, including the United States.

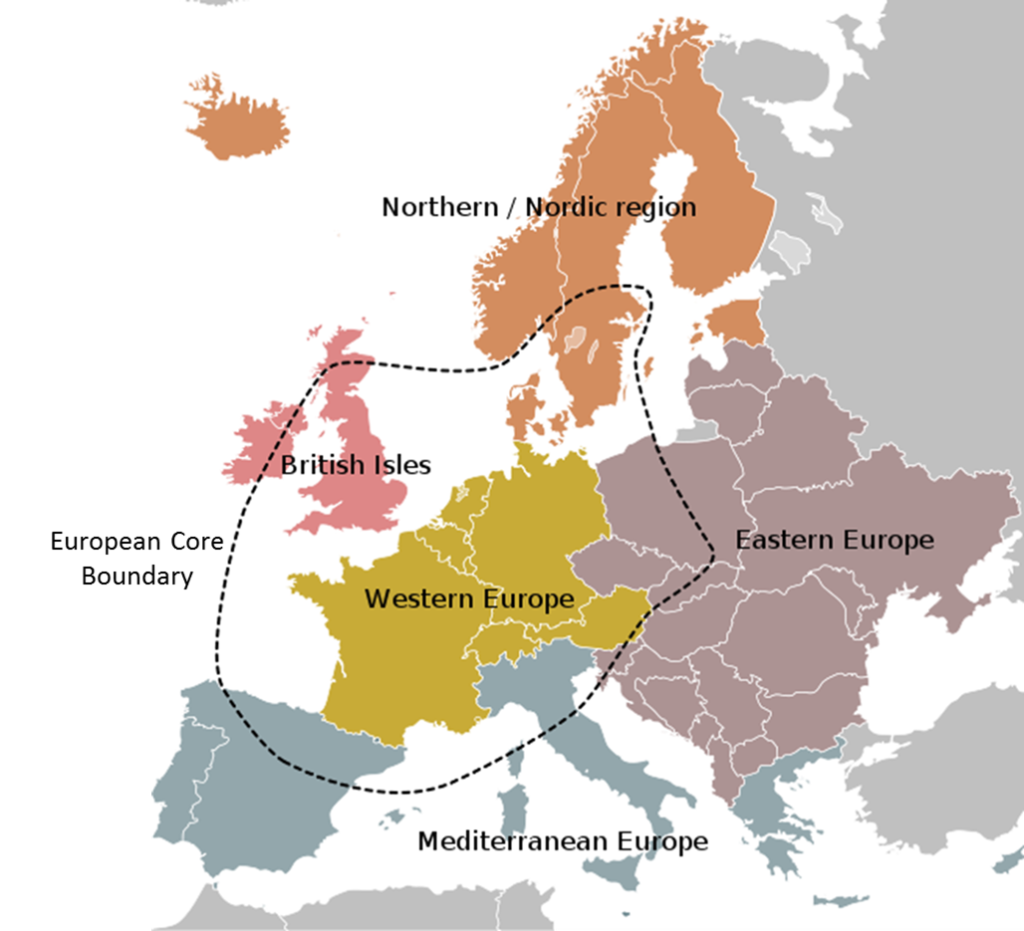

Today, the map of Europe reflects the changes brought about by the Industrial and Agrarian Revolutions as well as the political changes that took place throughout the time period. Europe’s core area, where economic output is highest, is largely centered around the manufacturing areas that arose during the Industrial Revolution (see Figure 2.10). These manufacturing areas in turn were originally located near the raw materials, such as coal, that could sustain industrial growth.

The shift in labor that occurred during the Industrial Revolution, as people left rural farms to find work in factories, led to the specialization of labor that is found in Europe today. Areas within Europe tended to specialize in the production of particular goods. Northern Italy for example, has maintained a specialty in the production of textiles. Germany continues to specialize in automotive manufacturing. The Benz Patent-Motorwagen, the world’s first gasoline powered automobile, was first built in Germany in 1886 and would later develop into the Mercedes-Benz corporation. As regions focused on the manufacture of particular goods, they benefited from economies of scale, the savings in cost per unit that results from increasing production. If you wanted to build a chair, for example, you’d have to buy the wood, glue, and screws as well as the tools needed to construct it, such as a drill, sander, and saw. That single chair would be quite costly to produce. If you wanted to make ten chairs, however, those same tools could be used for every chair, driving the cost of each chair down. Many areas in Europe have shifted from more traditional to high-tech manufacturing and industrial output in the region remains high.

2.4 European Migration

The Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions shaped both migration patterns within Europe and immigration to the region. Migration refers to a move from one place to another intended to be permanent. When considering migration, geographers look at both intraregional migration, movement within a particular region, and interregional migration, such as migration from Europe to North America. Geographers who study migration also investigate push and pull factors that influence people to move. Push factors are those that compel you to move from your current location. A lack of job opportunities, environmental dangers, or political turmoil would all be considered push factors. Pull factors, on the other hand, are those that entice you to move to a new place, and might include ample jobs, freedom from political or religious persecution, or simply the availability of desirable amenities. Historically, most intraregional migration in Europe was rural to urban, as people moved from farms to cities to find work. Cities grew rapidly in the region as centers of trade and industry.

Before the industrial revolution, migration to the region was usually in the form of invasions, such as with the Roman Empire, the Islamic Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. One notable, historical migration that did not represent an invading empire was the Jewish diaspora following the conquest of Judea, the region now known as Israel and Palestine, by a number of groups including the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Romans. A diaspora refers to a group of people living outside of their ancestral homeland and many Jewish people moved to Europe to escape violence and persecution, particularly after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Jews migrating to Europe were often met with anti-Semitism, however. During the Middle Ages, European Jews were routinely attacked and were expelled from several countries including England and France. Jewish communities were destroyed during the mid-14th century as the Black Death swept across Europe and thousands of Jews were murdered, accused of poisoning the water and orchestrating the epidemic. In actuality, the disease was likely spread by rats, and worsened by the superstitious killing of cats in the same time period.

European Jews were often forced to live in distinct neighborhoods, also known as ghettos. In fact, this requirement to live in specific areas was required in Italy under areas ruled by the Pope until 1870. These distinctive communities were often met with suspicion by European Christians, many of whom continued to foster the same anti-Semitic sentiment that had been prevalent during the Middle Ages.

This anti-Semitic fervor and persecution of Jews reached its height at the time of the Nazi Party’s rule in Germany. Prior to World War II, close to 9 million Jews lived in Europe; 6 million of them were killed in the Holocaust, the European genocide that targeted Jews, Poles, Soviets, communists, homosexuals, the disabled, and numerous other groups viewed as undesirable by the Nazi regime. Following the war, many surviving Jews emigrated back to the newly created state of Israel. Around 2.4 million Jews live in Europe today.

There was another shift in population after the signing of the Schengen Agreement in 1995, with large numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe migrating to the western European countries in the core. Citizens of European Union countries are permitted to live and work in any country in the EU, and countries like the Germany, Italy, and Spain contain large numbers of Eastern European immigrants. Around half of all European migrants are from other countries within Europe.

Economic and political inequalities have driven much of the interregional migration to Europe since the 1980s. Immigrants from North Africa and Southwest Asia, for example, driven by limited employment opportunities and political conflict, have migrated to Europe in large numbers and now represent approximately 12 percent of all European migrants.

2.5 Shifting National Identities

What does it mean to be European? Perhaps simply it means someone who’s from Europe. But what does it mean to be French or German or Spanish or British? These countries have long been comprised of a number of different ethnic and linguistic groups (see Figure 2.11). Spain, for example, not only contains groups speaking Spanish, the language of the historic Castilian people of the region, but also the Basque-speaking region in the north, the Catalan-speaking region centered around Barcelona, and numerous other distinct language groups. The United Kingdom, while comprised primarily of people who identify as “English,” also includes the areas of Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, each with a distinct linguistic and cultural identity. The Welsh are actually believed to be the oldest ethnic group within the United Kingdom, so perhaps they could argue that they represent the original national identity.

Before the creation of states as we understand them today, Europe, as with the rest of the world, was divided largely by ethnicity or tribe. Empires often took control of multiple ethnic areas. Familial allegiances were of fundamental importance. That’s not to say that geography or territory didn’t matter, but simply that who you were mattered more than where you were.

The creation of sovereign political states changed this notion. Multiple ethnicities were often lumped together under single political entities, sometimes due to peaceful alliances and sometimes due to armed conquest. In cases where a state was dominated by a single, homogeneous ethnic and linguistic cultural identity, we would refer to it as a nation-state, from the term state, meaning a sovereign political area, and nation, meaning a group with a distinct ethnic and cultural identity. Several European countries today are considered nation-states, including Poland, where 93 percent of the population is ethnically Polish, and Iceland, which is 92 percent Icelandic. Historically, countries like France and Germany were also considered nation-states, though immigration has changed their cultural landscape.

The concept of nation-state is distinct from the idea of nationalism, which refers the feeling of political unity within a territory. National flags, anthems, symbols, and pledges all inspire a sense of belonging amongst people within a geographic area that is distinct from their ethnic identity.

What happens when feelings of nationalism and national identity are linked with a particular ethnic group? In cases where a particular ethnic group represents the majority, nationalist ideals might be representative of that group’s language or religion. But what if there are other, minority ethnic groups that are excluded from what people think it means to be part of a particular state’s nationalist identity?

Migration has continually changed the cultural landscape of Europe and as immigrant groups have challenged or been challenged by ideas of nationalism. In 1290 CE, King Edward I expelled all Jews from England, essentially establishing Christianity as being at the core of English national identity. This expulsion lasted until 1657 CE. In France after the French Revolution, ideas of nationalism included “liberty, equality, and fraternity,” and extended into areas they conquered. In Germany, what it meant to be “German” under the Nazi Party excluded those who were considered to be “undesirable” and “enemies of the state,” such as Jews, Roma (sometimes referred to as Gypsies), persons labeled as “homosexuals,” communists, and others. Under Benito Mussolini, Italian nationalism excluded Slavs, Jews, and non-white groups.

Nationalism, taken to this extreme, is known as fascism. Fascists believe that national unity, to include a strong, authoritarian leader and a one-party state, provides a state with the most effective military and economy. Fascist governments might thus blame economic difficulty or military losses on groups that threaten national unity, even if those groups include their own citizens.

Within every country, ideas of nationalism grow, weaken, and change over time. Centrifugal forces are those that threaten national unity by dividing a state. These might include differing religious beliefs, linguistic differences, or even physical barriers within a state. Centripetal forces, on the other hand, tend to unify people within a country. A charismatic leader, a common religion or language, and a strong national infrastructure can all work as centripetal forces. Governments could also promote centripetal forces by unifying citizens against a common enemy, such as during the Cold War. Although the countries of Europe always had a significant amount of ethnic and linguistic variety, they typically maintained a strong sense of national identity. Religion in particular often worked as a centripetal force, uniting varying cultural groups under a common theological banner.

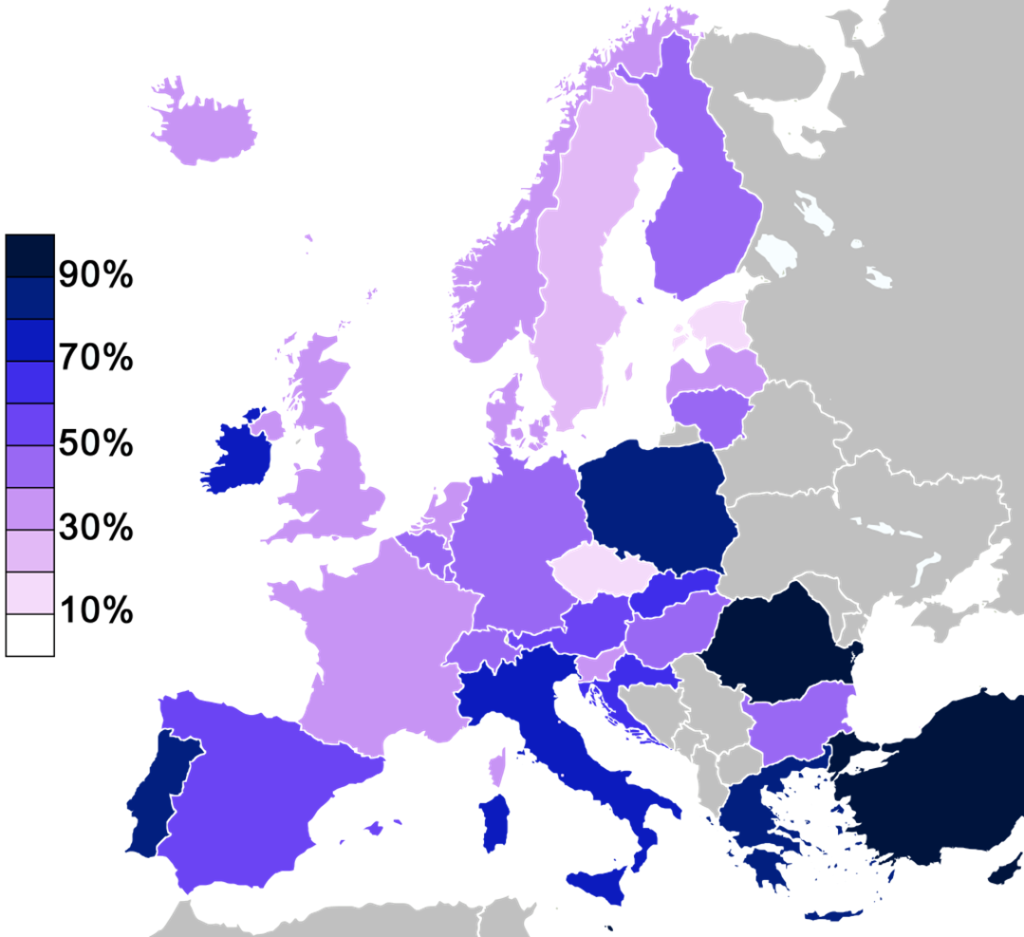

Religious adherence in Europe is shifting, however. In Sweden, for example, over 80 percent of the population belonged to the Church of Sweden, a Lutheran denomination, in 2000. By 2014, only 64.6 percent claimed membership in the church and just 18 percent of the population stated that they believed in a personal God (see Figure 2.12). This is indicative of a broad shift in Europe from traditional, organized religion toward humanism or secularism. Humanism is a philosophy emphasizing the value of human beings and the use of reason in solving problems. Modern humanism was founded during the French Revolution, though early forms of humanism were integrated with religious beliefs. Secular humanism, a form of humanism that rejects religious beliefs, developed later. Secularism refers broadly to the exclusion of religious ideologies from government or public activities.

Geographers can examine how secularization has occurred in Europe; that is, how Europe has been transformed from countries with strong religious values to a more nonreligious society. In general, areas within the core of Europe tend to be more secular and thus some researchers link secularization with rising economic prosperity. Most Western European countries have strong social welfare programs, where citizens pay a higher percentage of taxes to support universal healthcare, higher education, child care, and retirement programs. These social welfare programs often serve as centripetal forces, unifying a country by providing government support and preventing citizens from falling into extreme poverty.

2.6 Current Migration Patterns and Debates

The increasing secularization of Western Europe has magnified the conflict over immigration to the region. Whereas Western Europeans have become less religious over time, immigrants to the region are generally more religious. Increasing numbers of Muslim immigrants from North Africa and Southwest Asia have settled in Europe, lured by the hope of economic prosperity and political freedom. In 2010, around 6 percent of Europe identified as Muslim. That number is expected to grow to 10 percent by 2050. Muslims have the highest fertility rate among the major religious groups, so coupled with increasing immigration, this population is growing. In contrast, just under three-quarters of Europeans identified as Christian in 2010. This is expected to drop to 65 percent in 2050.

Europeans are divided about how open the region should be to immigrants, and how asylum seekers, refugees seeking sanctuary from oppression, should be treated. Even before the 2015 wave of Syrian migrants to Europe, a 2012-2014 survey showed that most Europeans (52 percent) wanted immigration levels to decrease. Opinions vary within the region, however. In the United Kingdom, 69 percent of people support decreased immigration. In Greece, a gateway country for migrants attempting to enter Europe, 84 percent of people desire decreased immigration. A majority of adults in Northern European countries, however, want immigration to stay the same or increase.

In 2014 and 2015, migration to Europe intensified as a result of an ongoing civil war in Syria. There were more refugees in 2014 than in any other year since World War II. 2015 shattered that record, however, as 65.3 million people were displaced. Germany has received the most applications for people seeking refugee status.

The journey for migrants is difficult and dangerous. Many attempt to cross by sea into Greece. Boats are often overcrowded and capsizing is common. Around 34 percent of refugees are children, many of them unaccompanied. Although the entire influx of refugees represents around 0.5 percent of Europe’s population, it is not necessarily the sheer number of refugees that poses a problem, but rather, the idea of how immigrant populations might change the identity of a nation-state.

Many small towns in Europe have experienced shifting demographics as people move away to work in cities and immigrants move in to work in the available jobs. As Western Europe moved through industrialization, it has increasingly shifted away from heavy manufacturing and increased employment in service and high-tech industries, a process known as deindustrialization. The higher-skilled and higher-educated workers from small towns moved to the cities to find work, while lower-skilled immigrants worked the often dangerous or labor intensive jobs that remained. In the United Kingdom in particular, many of the people who oppose immigration and supported Britain leaving the EU are located in these small towns where immigration has quite visibly changed the cultural landscape that had already shifted as a result of deindustrialization.

For some, the debate over immigration and asylum are less questions of national identity and more issues of social justice. Do countries that have political freedom and economic prosperity have a moral obligation to assist those in need? Historically, the answer has often been “no.” In 1938, on the brink of World War II, representatives from Western European countries voted not to accept Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria. Numerous countries in Europe have similarly voted not to accept Syrian migrants. Countries like Germany, which has accepted a relatively large number of asylum seekers, have been critical of other countries that have not been as welcoming. Sweden has specifically argued that if every country in Europe accepted a proportional amount of refugees, they would easily be able to accommodate the influx. Refugee populations typically have lower unemployment rates than native-born populations and though they require social services like housing and employment, can provide a long-term economic boost by increasing the labor force, especially in countries with otherwise declining populations.

Europe’s population will continue to shift in terms of demographics and cultural identity. Recent economic changes and migration patterns have highlighted deep divides about ideas of national identity and the role of the region in global affairs. Europe continues to be an influential and economically important region and will likely continue to attract migrants from surrounding areas.

the changes in manufacturing that began in the United Kingdom in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

the savings in cost per unit that results from increasing production

a move from one place to another intended to be permanent

a sovereign political area that has a homogenous ethnic and cultural identity

the feeling of political unity within a territory

forces that threaten national unity by dividing a state

forces that tend to unify people within a country

a philosophy emphasizing the value of human beings and the use of reason in solving problems

the exclusion of religious ideologies from government or public activities

a government policy where citizens pay a higher percentage of taxes to support universal healthcare, higher education, child care, and retirement programs