5

Learning Objectives

- Identify the key geographic features of Middle and South America

- Describe the primary patterns of colonial development found in Middle America

- Analyze the patterns of urban development in South America

- Explain how globalization has shaped current issues of inequality across Middle and South America

5.1 The Geographic Features of Middle and South America

Middle and South America (see Figure 5.1) cover an area of the world that is fragmented both in terms of its physical connectivity and its history. Generally, the continents of North American and South America are divided at the Isthmus of Panama, the narrow strip of land that connects the two large landmasses. Culturally, though, Middle America, including the Caribbean, is quite similar to South America and this region shares a distinct pattern of colonial development.

“Middle America” is typically defined as the area between North and South America, with Mexico sometimes categorized as North America and sometimes as Middle or Central America. Since Mexico shares strong cultural and historical similarities with the countries of Central America, they are grouped together in this text. This region also includes the islands of the Caribbean. South of Middle America is the continent of South America, extending from the the tropical sand beaches of Colombia to the frigid islands of southern Chile and Argentina.

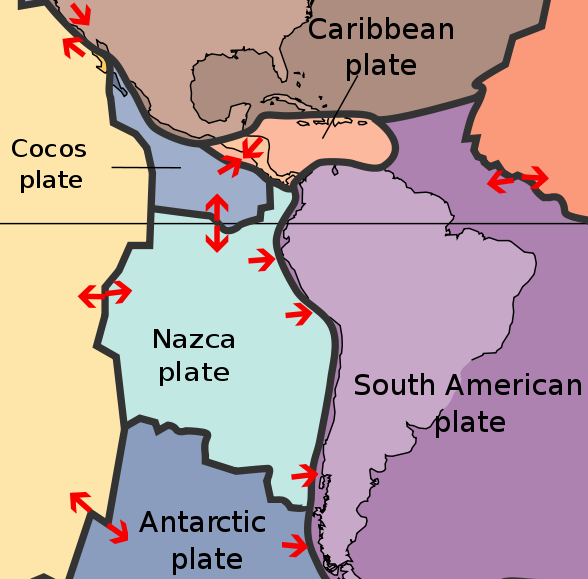

The region lies at the intersection of a number of tectonic plates making the region vulnerable to earthquakes and volcanoes (see Figure 5.2). Haiti, for example, located on the eastern half of the island of Hispaniola, is situated on the edge of the Caribbean plate along a transform plate boundary. A magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck here in 2010 killing over 100,000 people.

These tectonic collisions have created a landscape of relatively high relief, particularly in Middle America and western South America. Mexico is home to a number of impressive mountain ranges, including the Sierra Madre Occidental in the west, Sierra Madre Oriental in the east, and Sierra Madre del Sur in the south (see Figure 5.3).

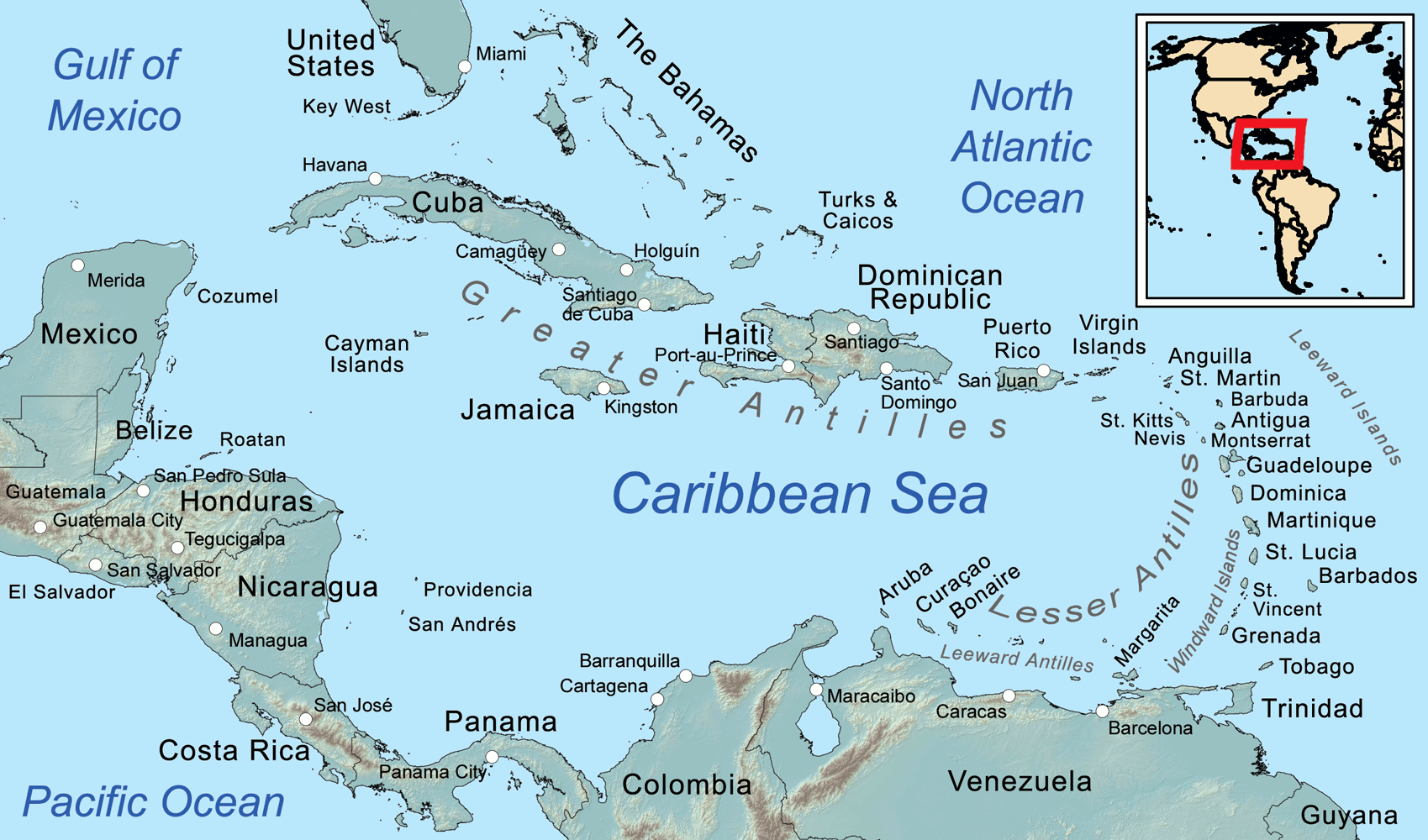

Further east, the tectonic collision of the Caribbean plate and the North American plate formed the Caribbean archipelago, or island chain. Many of these islands are the tops of underwater mountains. The islands of the Caribbean are divided into the Greater Antilles and the Lesser Antilles (see Figure 5.4). The Greater Antilles include the larger islands of Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and the Cayman Islands. The Lesser Antilles are much smaller and include the Leeward and Windward Islands, the Leeward Antilles, and the Bahamas.

In addition to earthquakes and volcanoes, the region is prone to tropical cyclones, also known as hurricanes. The areas along the Gulf of Mexico, in particular, lie in the path of frequent hurricanes. El Niño, the warming phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, also contributes to severe weather in the region. In North America, El Niño results in warmer than average temperatures, but it can also increase the number of tropical cyclones in the Americas and excessive rain across South America.

The high relief of Central America has created distinct agricultural and livestock zones, known as altitudinal zonation. As altitude increases, temperature decreases, and thus each altitudinal zone can support different crops and animals (see Figure 5.5). The hot, coastal area known as the tierra caliente, for example, can support tropical crops like bananas and rice. Past the tree line in the higher elevation of the tierra helada, animals like llamas can graze on cool grasses. In this way, even countries with a relatively small land area can support a wide variety of agricultural activities.

South America’s Andes Mountains, which stretch from Venezuela down to Chile and Argentina, were formed from the subduction of the Nazca and Antarctic plates below the South American plate. They are the highest mountains outside of Asia. Situated in the Andes is the Altiplano, a series of high elevation plains. These wide basins were central to early human settlement of the continent.

The rest of South America is relatively flat. The Amazon basin is the other key geographic feature of the continent (see Figure 5.6). The Amazon River is South America’s longest river and is the largest river in the world in terms of discharge. The river discharges 209,000 cubic meters (7.4 million cubic feet) every second – more than the discharge of the next seven largest rivers combined! Its drainage basin covers an area of over 7 million square kilometers (2.7 million square miles).

Numerous rivers snake across Central America, but the most prominent water feature is Lake Nicaragua. This large, freshwater lake is home to numerous species of fish and provides both economic and recreational benefits to the people of Nicaragua. Plans were approved to build a canal through Nicaragua to connect the Caribbean Sea to Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific Ocean though many worry about the ecological impacts of such a large-scale project.

Currently, the only connection between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean is through the Panama Canal. The canal was started in 1881 by the French, in what was then territory owned by Colombia, but the project was a failure. French construction workers were unprepared for the torrential Central American rainy season, dense jungle, and difficult geology. 22,000 workers were killed due to disease and accidents.

The United States helped Panama achieve independence from Colombia and in exchange, Panama granted the US rights to build and control the canal. In 1904, the US continued where the French had left off and in just ten years, the project was completed. Over 5,600 workers died during the US construction project. Panama regained control of the canal in 1999.

When the canal was completed, it accommodated around 1,000 ships per year. Today, around 15,000 ships pass through the canal each year. One key issue is that the Panama Canal’s waterways are almost entirely man-made and pass through areas of changing elevation. A series of locks take ships from lower-elevation waterways and raise or lower them depending on the direction the ships are headed. It takes around 8 to 10 hours for a ship to pass through. These locks were not built with modern ships in mind, however, and construction was undertaken to widen the locks to accommodate today’s massive container ships. The expansion project was completed in 2016.

5.2 Colonization and Conquest in Middle America

Middle America was settled by a number of indigenous groups who originally migrated to the region from North America. Some continued on through the Isthmus of Panama to South America. Here, they founded the Mesoamerican cultural hearth, considered one of the earliest civilizations in the world. Two groups in the region had a particularly strong impact on the cultural landscape of Middle America: the Maya and the Aztec.

The Maya Civilization began around 2000 BCE and stretched across present-day Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and the Yucatan peninsula. The civilization had a theocratic structure, with their king viewed as a divine ruler. They developed a system of hieroglyphic script, a calendar, a system of mathematics, and astronomy. The civilization had a number of city-states linked by a complex trading system. They also had monumental architecture, and a number of their buildings, like the pyramidal Chichen Itza, are still visible on the landscape today (see Figure 5.7). At its height, the Maya Empire encompassed over one million people.

So what happened to the Maya? The short answer is: we’re not really sure. It takes a carefully managed infrastructure to care for one million people. Some researchers think the civilization simply got too big too fast and any number of calamities, perhaps ecological damage or a disease epidemic, related to this rapid population growth could have had a devastating effect. Others think that infighting broke out within the society. Still others maintain that historical climate data shows a decrease in rainfall in the region around the time of the Maya’s decline, perhaps indicating a widespread famine. In any case, in such a large society, it would only take a small problem to send the system into turmoil and by the 9th century CE, the Maya had abandoned its cities and its empire collapsed.

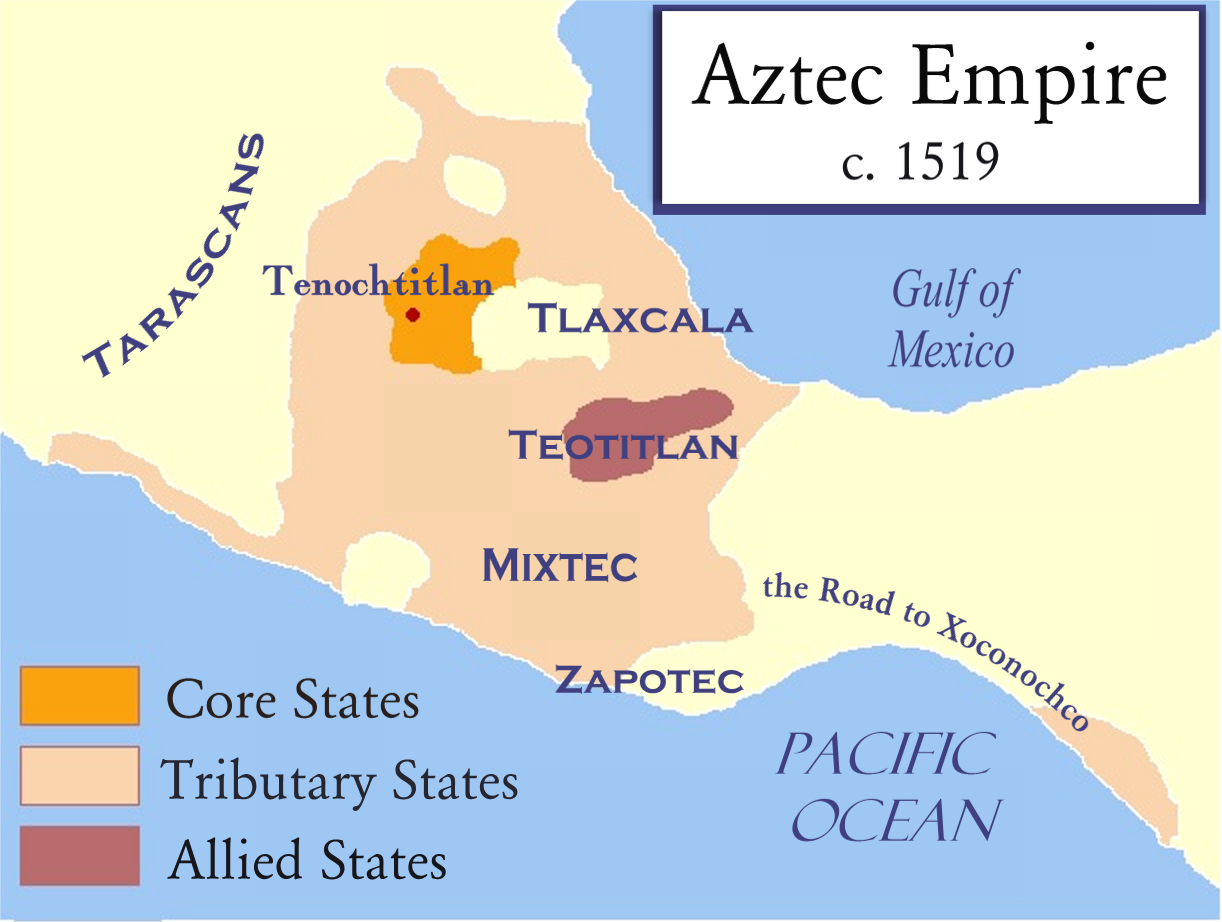

The Aztec Empire developed much later in history, during the 15th century CE (see Figure 5.8). This civilization was centered around Tenochtitlan which became its capital and one of the greatest cities in the Americas, with a population between 100,000 and 200,000 people. Today, the ruins of Tenochtitlan are located under present-day Mexico City. Aztec architecture, art, and trading systems were truly extraordinary for their time.

This empire was relatively short-lived, however, and the reason for its decline is much easier to pinpoint than the Maya. The Spanish, led by the conquistador Hernán Cortés, aligned themselves with a rival group and arrived in Tenochtitlan, as very unwelcome visitors, in 1520. Violence erupted and the Aztec leader Montezuma was killed, marking the beginning of the end of the civilization. By 1521, the Spanish and their allies had destroyed the city of Tenochtitlan and the Aztecs were subsequently ruled by a series of leaders who were chosen by the Spanish.

Colonization completely reshaped the Middle American landscape, from architecture to politics to land-holding patterns. Middle America can be divided into two different spheres, the mainland and the rimland, each with a distinct colonial history and experience (see Figure 5.9). The rimland, though a fragmented realm of islands, was more accessible for European colonists than the mainland and were among the first places explorers landed when they reached the Americas. Christopher Columbus first reached the rimland in 1492 CE and would reach South America on a third voyage in 1498 CE. The first Spanish cities in the Americas were established in the region during this time period. By the 1600s, England, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands were shipping Africans to the Americas to work on farms. Of the more than 11 million Africans who were sold as slaves and shipped overseas, over 90 percent were sent to the Caribbean and South America.

The rimland’s sprawling plantations where the slaves worked were focused on growing crops, most often sugar, for export. Prior to the commercial agriculture practiced on plantations, most in the region practiced subsistence farming, where farmers grow enough food to feed themselves and their families. Since subsistence farmers eat what they grow, they typically grow a variety of crops. You can only eat so much corn before you need a bit more variety. Plantation farms, however, were generally monocultures, meaning only a single crop was grown. This, combined with the free slave labor, allowed for maximum efficiency and profit. Labor was seasonal, coinciding with the seasonality of the cultivated crop. Today, the rimland is still home to a number of plantations and the blending of European and African cultures is prominent on the landscape.

In the mainland, there is a blending of both indigenous and Spanish cultures. There is an ethnic blending as well. Mestizo refers to someone of mixed European and Amerindian, or indigenous American, descent and a number of Middle and South American countries have a sizable mestizo population. The Spanish conquest of mainland Middle America not only toppled the Aztec civilization but also led to the deaths of millions of indigenous people due to war and disease.

In contrast with the plantations of the rimland, the mainland was more commonly home to haciendas, Spanish estates where a variety of crops were grown both for local and international markets. Because of this variety, workers lived on the land, unlike the seasonal laborers needed to work plantations. Furthermore, although haciendas were less efficient than plantations, they were also less vulnerable economically. If you’re only growing one crop and the price of that crop declines, you have no backup. Similarly, disease or a bad harvest could dramatically decrease profits. The increased diversity in crops grown on a hacienda decreased risk. Haciendas also had an element of social prestige. The size of the hacienda increased the social standing of the landowner, and hacienda farmers were often given their own plots of land to cultivate.

Broadly, the colonization of Middle America led to land alienation, where land is taken from one group and claimed by another. Where indigenous groups might have previously controlled their own subsistence farms, wealthy European settlers took over the land and built haciendas – often then employing those whose land they claimed. Today, poverty continues to be a significant issue among the indigenous people of Middle and South America and the current system of land ownership found in the region directly connects to European colonization.

5.3 The South American Colonial Landscape

A variety of ancient cultures were found in South America prior to colonization. These indigenous groups settled in a variety of environments, some in the coastal plains and others in the Amazon basin. One group, the Inca, primarily settled in the altiplano of Peru beginning in the 13th century. The Inca Empire was the largest of the pre-Colombian, referring to before Columbus’ arrival, civilizations. Initially, the Inca founded the city-state Kingdom of Cusco, but over time, expanded to encompass four territories stretching 2,500 miles and included over 4 million people.

In 1494 CE, Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing up territory in the New World between the two colonial empires (see Figure 5.10). The Spanish would control territory to the west of the line while Portugal would control territory to the east. Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro reached the Inca by 1526 CE. The empire, already weakened by smallpox and infighting, was conquered by the Spanish soon after. Portugal meanwhile conquered much of eastern South America in present-day Brazil.

In coastal South America, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom established colonies (see Figure 5.11). These colonial possessions were largely extensions of the Central American rimland with large plantations and slave labor. Portugal, too, established plantations along coastal Brazil. As colonialism expanded, the colonial empires prospered. Lima, for example, in present-day Peru, became one of the wealthiest cities in the world due to its silver deposits.

Colonization dramatically changed the urban landscape of the Americas as well as rural development patterns. Development broadly refers to economic, social, and institutional advancements and levels of development vary widely across the region. In the rural areas of South America, land was taken from indigenous groups, as it had been in Middle America, and transformed to the benefit of colonial interests. The main interest of the conquering group was to extract riches with little thought given to fostering local development and regional connectivity. Even today, many of the rural areas of South America remain highly isolated and the indigenous descendants of conquered Amerindian groups among the poorest in the region.

In cities that were conquered, European colonizers typically razed existing structures and built new ones. In general, there was little regard for local development and cultural values. The Spanish colonies, for example, were governed according to the Laws of the Indies. These laws regulated social, economic, and political life in territories that were controlled by Spain. They also prescribed a very specific set of urban planning guidelines, including building towns around a Plaza Mayor (main square) and creating a road network on a grid system. Even today, the cities of the Americas often look quite European. In Mexico City, for example, the Spanish destroyed the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and built the Mexico City Cathedral over the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor complex (see Figure 5.12).

In the early 19th century, most of the colonies of Middle and South America gained their independence, often led by the Europeans who had settled in the region. Larger colonial possessions often separated into smaller independent states. For a short time, the states of Central America formed a federal republic, but this experiment devolved into civil war. Today, most of the mainland of Middle and South America is independent, with the exception of French Guiana which is maintained as a French territory and is home to a launch site for the European Space Agency. Many of the island nations are still controlled by other countries. France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands all still have territories in the Caribbean.

5.4 Urban Development in South America

South America is a highly urbanized region, with over 80 percent of people living in cities. Central America and the Caribbean are slightly less urbanized at around 70 percent. Development and human settlement are not spread evenly across the region, however. Several countries in Middle and South America have a primate city. Primate cities are those which are the largest city in a country, are more than twice as large as the next largest city, and are representative of the national culture. For example, of Uruguay’s 3.4 million people, over half live in its capital and primate city of Montevideo. Not all countries of the world have a primate city. Germany’s largest city is Berlin, which is roughly twice as large as Hamburg and Munich and was once the country’s primate city. In recent years, however, Munich has increasingly become Germany’s cultural center.

The region is also home to several megacities. A megacity is a metropolitan area with over 10 million people. Mexico City, the capital and primate city of Mexico, has a population of 22 million people. São Paulo, Brazil has 21.5 million. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Buenos Aires, Argentina are also megacities. Megacities often face distinct challenges. With over 10 million people comes a significant need for affordable housing and employment. Megacities often have large populations of homeless people and, particularly in Middle and South America, sprawling slums. This immense population also needs a carefully managed infrastructure, everything from sanitation to transportation, and the developing countries of this region have historically had difficulty meeting the demand.

Despite the challenges faced by large urban populations, rural to urban migration continues in the region. As in many parts of the world, poor rural farmers migrated to the cities where industrial development was clustered in search of work.

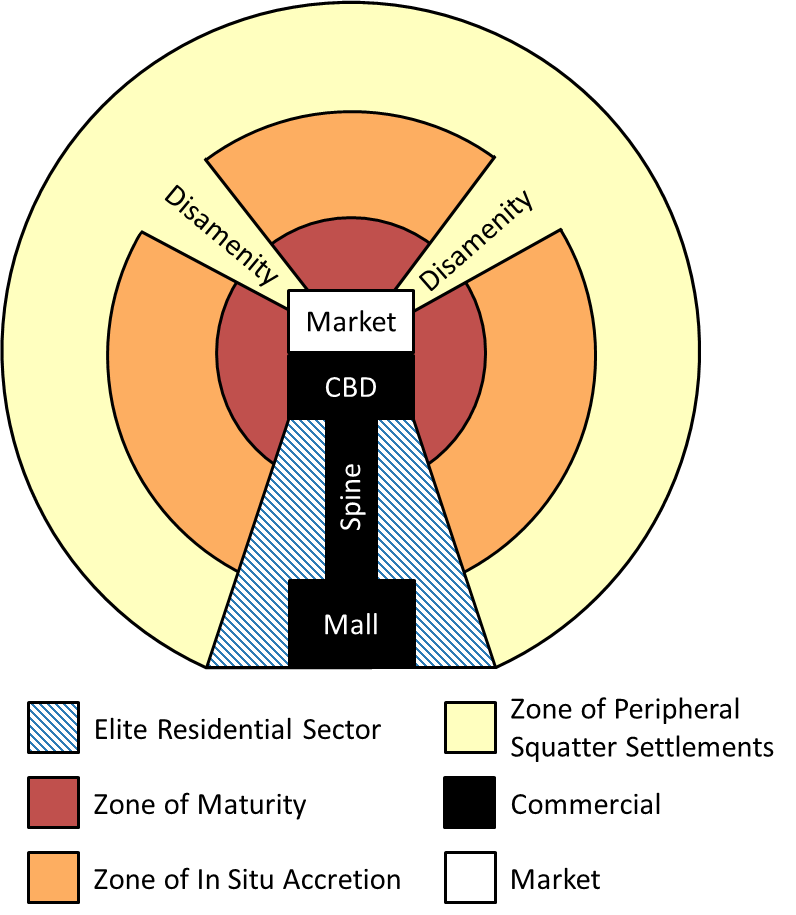

In general, the cities of Middle and South America follow a similar model of urban development (see Figure 5.13). The central business district, or CBD, is located in the center of the city often alongside a central market. While some colonial buildings were demolished following independence, cities in this region still typically have a large plaza area in the CBD. As industrialization occurred, additional industrial and commercial development extended along the spine, which might be a major boulevard. The spine is often connected to major retail area or mall.

Surrounding the commercial area of the spine is the elite residential sector consisting of housing for the wealthiest residents of the city often in high-rise condominiums. Around the CBD is the zone of maturity, an area of middle class housing. The zone of in situ accretion is a transitional area from the modest middle class housing of the zone of maturity to the slums of the city’s poorest residents.

The outermost ring in a typical Latin American city is the zone of peripheral squatter settlements. In this zone, residents do not own or pay rent and instead occupy otherwise unused land, known as “squatting.” In some cases, residents in this zone earn money by participating in the informal sector where goods and services are bought and sold without being taxed or monitored by the government. Disamenity sectors arise along highways, rail lines, or other small tracts of unoccupied land where the city’s poor often live out in the open. Residents often build housing out of whatever materials they can find such as cardboard or tin. What is perhaps most striking about the Latin American city is that in some areas, the city’s poorest residents live in an area adjacent to the wealthiest residents magnifying the income inequality that is present in the region.

Globally, around one-third of people in developing countries live in slums, characterized by locations with substandard housing and infrastructure. Estimates vary regarding the total number of people who live in slums but it is likely just below 1 billion people and continues to climb. In Brazil, these sprawling slums are known as favelas and over 11 million people in this country alone live in favelas. Rocinha, located in Rio de Janeiro, is Brazil’s largest favela and is home to almost 70,000 people (see Figure 5.14). It has transitioned from a squatter area with temporary housing to more permanent structures with basic sanitation, electricity, and plumbing.

In some cases, those who live in the slums of Middle and South America are not unemployed but simply cannot find affordable housing in the cities. Rural to urban migration here, as in other parts of the world, has outpaced housing construction. Even some lower and middle managers are unable to find housing and thus end up living in the slums.

5.5 Income Inequality in Middle and South America

Although income inequality in Middle and South America has fallen in recent years, this region remains by some measures the most unequal region in the world. Overall, the top 10 percent of people in Latin America control around 71 percent of the region’s wealth. If current trends continue, the top 1 percent will have amassed more wealth than the bottom 99 percent. In Mexico, around half of the population lives in poverty and while the rich in Mexico have seen their wealth climb dramatically in recent years, poverty rates remain relatively unchanged. In Brazil, the wealthiest 10 percent of the population own almost three-quarters of the country’s wealth, around the same as in the United States. This inequality has been a product of geography but has also impacted the landscape, as well.

Farmers in Middle and South America have struggled with land ownership after their alienation from the land during colonization. While countries like Spain and Portugal no longer control land in Middle and South America, many of these countries’ governments took over colonial landholdings during independence rather than turning it back over to private farmers. Often, small farmers in the region simply can’t compete with the large-scale agricultural producers. This either worsens rural poverty or contributes to rural to urban migration as farmers leave to find work elsewhere.

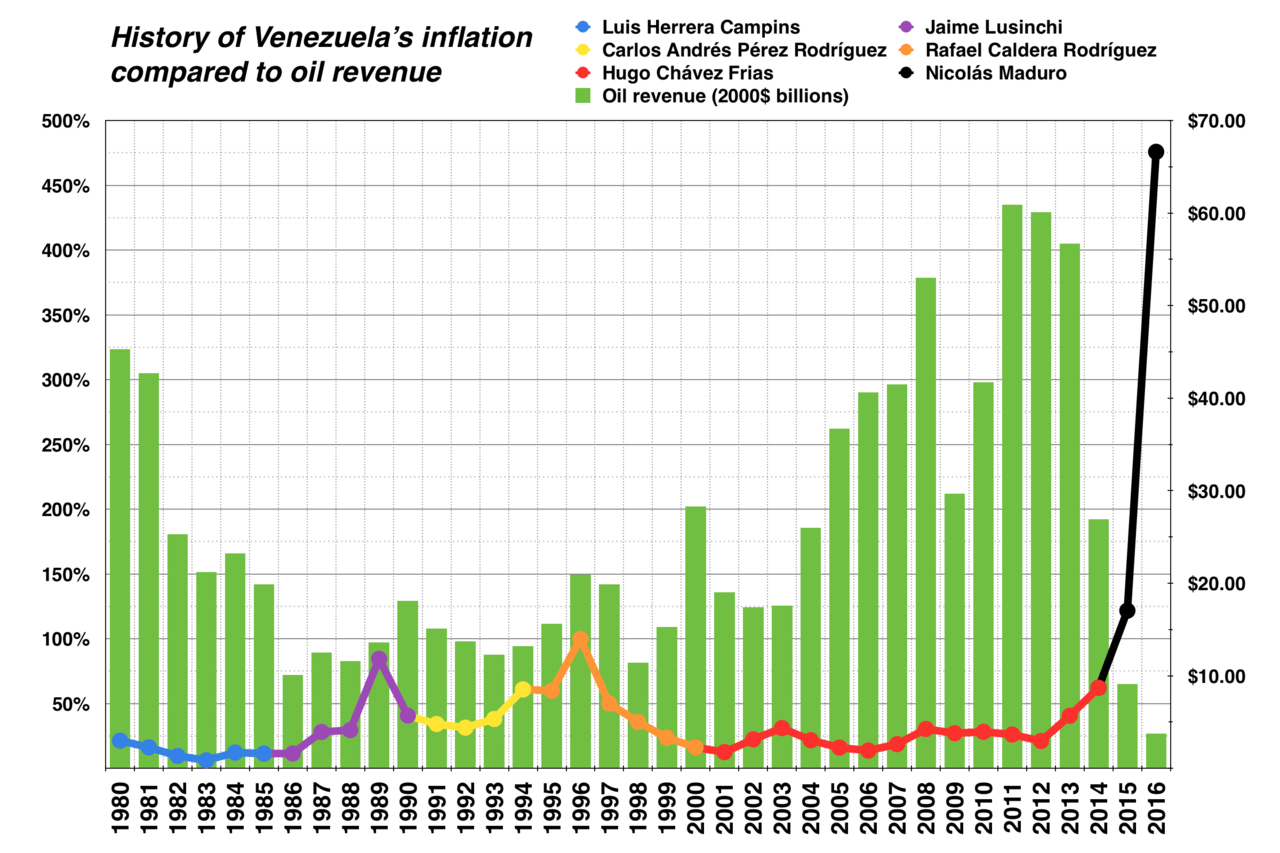

Government responses to income inequality vary. Some countries of Latin America and the Caribbean turned to socialism in the hope that government-controlled development would be able to more fairly distribute wealth. Often these socialist endeavors were financed with the exports of natural resources, such as oil or coffee, but this created a vulnerable dependency on foreign trade. In Venezuela, for example, where Hugo Chavez ushered in a socialist revolution at the turn of the 21st century, falling oil prices in 2016 threw the economy into steep decline leading to massive inflation and a shortage of domestic products (see Figure 5.15). Governments like Venezuela often relied too heavily on income from exports and invested little in developing their own infrastructure, instead simply relying on importing the goods they needed. In general, spending on social services remains relatively low across the region.

Taxation systems have had a relatively minimal effect on bettering the lives of the region’s poor or assisting the region in infrastructure development. The wealthiest people in many of these countries hold their money offshore in order to avoid taxation, but this also prevents governments from being able to use this tax revenue. Many governments have also given tax breaks to large, multinational corporations who seek to do business in the region providing a short-term economic increase at the expense of long-term development planning.

Inequality is not just an issue of poverty, however. It can also relate to unequal access to education and political power. 62 percent of the population of Bolivia is indigenous, for example, but the country did not have a president from indigenous descent until Evo Morales was elected in 1998. Among the indigenous population of Bolivia, most work in agriculture and around 42 percent of indigenous students do not finish school compared to just 17 percent of non-indigenous students. There is a distinct cycle between education and poverty with educational advancement directly linked to economic advancement. In some areas, access to adequate education, particularly among indigenous populations, remains low, limiting the opportunity to narrow the income gap.

For some, liberation theology has provided a sense of hope. Liberation theology is a form of Christianity that is blended with political activism. There is a strong emphasis on social justice, poverty, and human rights. This approach also stresses the importance of alleviating poverty through action and followers believe that, like Jesus, they should align themselves with society’s marginalized groups.

Others in the region have decided to look elsewhere for economic advancement. Most countries in Middle and South America have net out-migration, meaning more people are leaving than coming into the country. Around 15 percent of all international migrants are from Latin America and the United States continues to be top destination. Some from Central America, however, are choosing to stay in Mexico rather than continue the journey north to the United States.

5.6 Patterns of Globalization in Middle and South America

The ongoing migration from Middle and South America points to a larger issue of global economic connectivity. Many of the region’s migrants are well-educated and leave in search of better economic opportunities. This contributes to brain drain, referring to the emigration of highly skilled workers “draining” their home country of their knowledge and skills. Around 84 percent of Haiti’s college graduates live outside of their home country, for example, the greatest percentage of any country in the world.

When workers leave the region in search of work elsewhere, they often send home remittances, or transfers of money back to their home country. In 2014, global remittances totaled $583 billion, and in some countries, remittances represent a significant portion of the country’s GDP, in some cases exceeding the amount the country earns from its largest export. Mexico’s remittances alone totaled over $25 billion in 2015, or around 2 percent of its total GDP. Most remittances in Middle and South America originate in the United States.

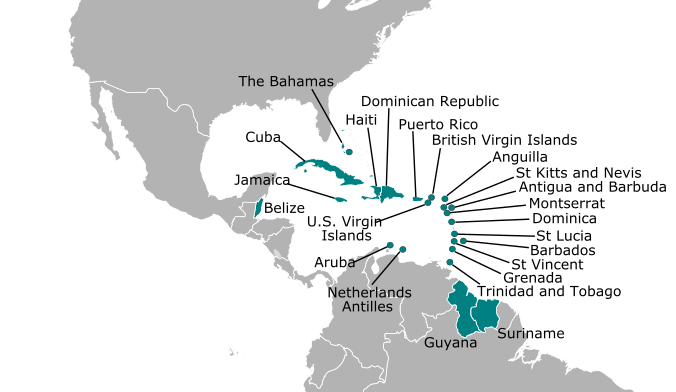

As countries in this region have sought to increase development, they have faced several challenges. Exports continue to flow from Latin America and the Caribbean to the rest of the world, though often coming at the cost of economic diversification. The island nations of the Caribbean have had particular challenges to sustainable development due to their small size and populations and limited natural resource base. These countries are referred to as Small Island Developing States, or SIDS (see Figure 5.16). These countries have struggled with high technology, communication, energy, and transportation costs and have had difficulty developing in a way that doesn’t harm their fragile ecosystems. In the Caribbean, the SIDS have formed the Caribbean Community, or CARICOM, aimed at promoting economic integration and cooperation among its member countries.

Some countries, particularly those in the Caribbean, have advanced their economies through offshore banking. Offshore banks are located outside a depositor’s country of residence and offer increased privacy and little or no taxation. When the wealthy utilize offshore banks, they can thus avoid paying taxes on income that would be otherwise taxable in their home country. Belize, Panama, the Bahamas, the Virgin Islands, and many other countries in the region have become popular locations for offshore banks. The Cayman Islands, though, is one of the world’s leading offshore banking locations. Around $1.5 trillion in wealth is held in the Cayman Islands and the British territory has branches for 40 of the 50 largest banks in the world. As a result, it has a GDP per capita of over $49,000 compared to just $8,800 for its much larger neighbor, Jamaica. Some countries have tried to strengthen their tax laws to prevent tax evasion through offshore banking.

Others in the region have turned to the production and trade of illicit drugs as a way to generate income, particularly cocaine and marijuana. Coca, the plant used to make cocaine, is grown and harvested in the Andes Mountain region, particularly in Bolivia, Columbia, and Peru. In 2013, Peru overtook Columbia as the global leader in cocaine production. The drug trade in Middle and South America has led to the rise of cartels, criminal drug trafficking organizations, and widespread violence in the region. Cartels often fight each other for territory, with civilians in the crossfire, and in many areas, drug organizations have infiltrated police, military, and government institutions. In Mexico alone, the ongoing Mexican Drug War between the government and drug traffickers shipping cocaine from Central America to global buyers has killed more than 100,000 people. The United States continues to be the largest market for illegal drugs. Americans purchase around $60 billion in illegal drugs annually, funding drug violence and drug trade in Middle and South America.

As countries throughout Middle and South America have increased their development, there have been some significant environmental concerns, particularly deforestation. When urban areas expand, forests are often cleared to make room for new housing and industry. Similarly, as agricultural lands expand and commercialize to feed growing populations and produce crops for export, it often leads to deforestation. Furthermore, nutrients in soil decline over time without careful land management, and thus after lands are intensively farmed for some time, soil fertility declines and new agricultural lands are cleared. Around 75 percent of Nicaragua’s forests have been cut down and converted to pasture land. The Amazon rainforest, which amazingly holds around 10 percent of the entire world’s known biodiversity, is down to around 80 percent of its size in 1970. The majority of the deforestation in the Amazon has occurred as a result of the growth of Brazil’s cattle industry and its global export of beef and leather.

Despite slowing rates of deforestation and strides to address income inequality, this region remains largely in the global periphery. Some argue that it is to the advantage of countries like the United States to keep this region in the periphery, as it allows them to import cheap products. This idea is known as dependency theory, and it essentially states that resources flow from the periphery to the core, and thus globalization and inequality are linked in the current world system. While some have critiqued the specifics of the theory, others still see it as a useful way to understand the relationship between the core and the periphery. As Middle and South America continue to develop, they will face new challenges of how to do so in a way that is both ecologically and socially sustainable.

a narrow strip of land that connects the two large landmasses

a chain of islands

the warming phase of a climate pattern found across the tropical Pacific Ocean region

distinct agricultural and livestock zones resulting from changes in elevation

a series of high elevation plains found in western South America

an agricultural system designed to produce one or two crops primarily for export

where farmers grows food primarily to feed themselves and their families

a term referring to someone of mixed European and Ameridian descent

a Spanish estate where a variety of crops are grown both for local and international markets

when land is taken from one group and claimed by another

economic, social, and institutional advancements

a city that is the largest city in a country, is more than twice as large as the next largest city, and is representative of the national culture

a metropolitan area with over 10 million people

a housing area where residents do not own or pay rent and instead occupy otherwise unused land

refers to the part of the economy where goods and services are bought and sold without being taxed or monitored by the government

a form of Christianity that is blended with political activism and places a strong emphasis on social justice, poverty, and human rights

refers to the emigration of highly skilled workers “draining" their home country of their knowledge and skills

small, coastal states with that face challenges related to sustainable development and have limited populations and natural resource bases, also known as SIDS

financial services located outside a depositor’s country of residence and offer increased privacy and little or no taxation