Modern (1940’s-present)

42

Oliva Dubro

introduction

Imagine your local Starbucks – bustling with the sounds of aggressive Macbook typing, professional business phone calls, and the calling of customers’ names as they grab their daily dose of caffeine to help power through another task on their ever-growing to-do list. Now imagine that the Americanos being handed from barista to customer aren’t Americanos at all. Imagine employees passing little orange and blue pills across the counter. No need to worry about reusable straws or extra-strength cup lids; patrons just pop a capsule into their mouths and hustle back to their charger-strewn stakeout. So maybe that’s a reach, but we’ve all heard the stories (or maybe told the story) of the anxious student cramming for an exam in the library for hours, thanks to the help of a Starbucks latte or two (or four.) Recently, though, the story may take a different twist, as espresso shots and 5-Hour Energy’s just aren’t cutting it for many young adults try to rise above the pack of their peers. It may not be all that uncommon to hear about another study aid used – Adderall. “Well, our generation never needed it. Why does your generation always have to take it to the next level?” the Gen Xer asks (rather passive aggressively.)

The black hole of cell phone apps and distractions has left the developing brain in a constant state of fluctuation when it comes to cognitive abilities. In turn, many young adults suffer from symptoms similar to those seen in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), causing them to seek the help of prescription stimulants to treat the inattention and misdirection of motivation caused by a cell-phone-centric life.

The Life & Times of (Legal) Amphetamine

Amphetamine, a popular stimulant prescription treatment for ADHD, isn’t a new discovery compared to iPhones, tablets, Synthesized by Dr. Gordon A. Alles in 1927, amphetamine was introduced to the public in 1937 as a ‘miracle cure’ for children who suffered from “severe behavioral problems” (Heal, et. al, 2013). Dr. Charles Bradley was the first to report the benefits of Benzedrine (the former brand name for the amphetamine currently known as Adderall) on these children, noting “These therapeutic benefits unequivocally derived from the drug because they were apparent from the first day of Benzedrine treatment and disappeared as soon as it was discontinued” (Bradley, 1937).

A Dance with Dopamine and Subsequent Inattention

You may have the urge to whip out your phone to take a quick little ‘study break,’ even if only to check your notifications; (There’s that inattention we mentioned earlier.) Don’t worry – you aren’t alone. Notifications are small but powerful sources for dopamine, a neurotransmitter “the average smartphone user checks their device 80-110 times a day.” in the brain that is responsible for pleasure. Dopamine is the same chemical released when we smoke, drink, gamble, and even eat. Coincidence that all of the aforementioned activities have addictive qualities? Not at all. It’s no wonder the average smartphone user checks their device 80-110 times a day (Elola, 2017)!

“The new technological landscape is leading us to what neuropsychologist Dr. Alvaro Bilbao calls the monkey mind attention style – a mind that jumps from one thing to another, back and forth.” (Elola, 2017) According to Bilbao, this “monkey mind” philosophy is the effect of notification-induced dopamine firing and our desire for more. Essentially, he postulates that attention is constantly “jumping” between the task at hand and our devices as a result of the addictive nature of digital media.

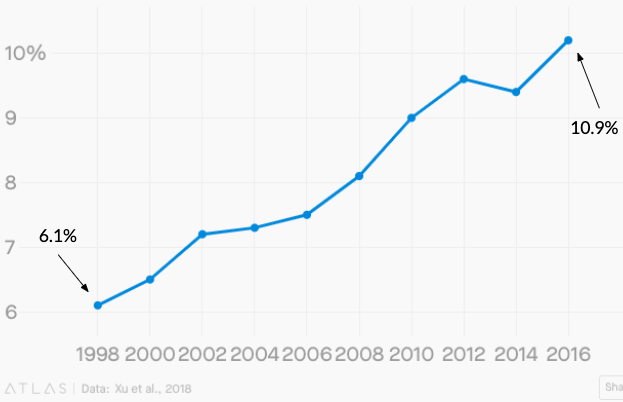

A study conducted in 2018 concluded “a statistically significant association was found between higher frequency of digital media use and subsequent symptoms of ADHD” (Ra, et. al, 2018), which may be a plausible catalyst for the increased prevalence in ADHD disorders over the past decade. This statement isn’t to suggest that your iPhone is giving you ADHD, but digital media usage may perpetuate symptoms seen in ADHD cases.

Stimulant Support in the Quest To Improved Focus

How can we be the nation’s next great innovators if we can’t even make it through a full episode of Game of Thrones, let alone a boring work assignment, without getting distracted by digital notifications?

“During the last few years, the number of requests for ADD evaluations has hugely increased,” Paula Stoessel, Ph.D., director of mental health services for physicians in training at the University of California, Los Angeles (Lakhan & Kirchgessner, 2012).

Since there is no test to definitively rule a patient as suffering from ADHD, physicians typically rely on self and peer reports to diagnose the disorder. The more people that report troubling inattention, the more diagnoses made – and the more prescriptions written.

Medication & Motivation

But ADHD isn’t just a lack of attention; it’s a multifaceted disorder that involves deficits in the brain’s executive functioning. If amphetamine act solely as a supplement for these deficiencies, than someone without ADHD technically shouldn’t be affected by the drug.

Despite this, Adderall is known as a “smart drug” and is the second most misused drug by undergraduate-aged young adults (Lakhan & Kirchgessner, 2012). So what is it about Adderall and other stimulants that makes a deficit-free brain feel like the Incredible Hulk?

Neuroscience researchers Irena Ilevia and Martha Farah proposed the theory that amphetamines and other prescription stimulants affect more than just cognitive ability:

“Psychostimulants like Adderall and Ritalin are widely used for cognitive enhancement by people without ADHD, although the empirical literature has shown little conclusive evidence for effectiveness in this population. [We explored] one potential explanation of this discrepancy: the possibility that the benefit from enhancement stimulants is at least in part motivational, rather than purely cognitive” (Ilieva & Farah, 2013).

Prescription amphetamines target the regulation of dopamine (that’s right – the same dopamine your phone targets.) MPH and d-AMP, generic versions of widely prescribed stimulants in the treatment of ADHD, both enhance dopamine signaling in the brain (Lakhan & Kirchgessner, 2012). …the possibility that the benefit from enhancement stimulants is at least in part motivational, rather than purely cognitive”These drugs significantly increased dopamine in the prefrontal and temporal regions of the brain, areas that are associated with attention, as to be expected. The kicker? The drugs also increase dopamine in what’s known as the ventral striatum, a brain region highly involved in motivation and reward systems (Lakhan & Kirchgessner, 2012).

Learn More About Brain Regions & Their Functions Here!

Basically, prescription stimulants activate dopamine in the brain’s “Get ‘er done” region. Have you ever heard a friend say Adderall/Ritalin/Vyvanse “makes learning fun”? The National Center for Biotechnology Information details the use of Benzedrine as an “energy pill” during World War II, with around 150 million tablets distributed to American and British personnel during their service (Heal et al., 2013).

These prescription stimulants boost motivation to perform the task, and to perform it well. They also boost the amount of pleasure we experience while completing the task.

Digital media affects brain areas involved with motivation, too, but notifications just don’t satisfy the dopamine fiend within each of us quite like a pill absorbed right to the bloodstream.

From Amphetamines to Excellence

If this is all true, why shouldn’t we all just take adderall?

At least it’s making us more productive, unlike drugs like marijuana or even prescription painkillers, right?

Shouldn’t we use our resources to be as productive as we can?

These questions illustrate the infamous “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger” mentality Americans are known for (and often teased about.) There has always been an intense societal pressure for young adults of the generation to contribute to “American Exceptionalism”,but young adults today must also prove to their senior coworkers that they are more than just “lazy millennials”.

In a study on the media portrayal of neuroenhancement sources, researchers found that 95% of the articles in question mentioned at least one potential benefit of using prescription psychostimulants, while only 58% mentioned a single risk or side effect (Partridge et al., 2011). Instead of finding ways to minimize stress, Americans are taught to find more ways to endure stress and psychostimulants fit the bill. 95% of the articles in question mentioned at least one potential benefit of using prescription psychostimulants, while only 58% mentioned a single risk or side effect.The Millennial Generation and Generation Z are the first generations to be exposed to such intense digital media distractions, yet it’s unacceptable (by law) to overcome these obstacles with the help of psychostimulants.

So what’s the solution?

It’s important to promote educational materials explaining:

-

Appropriate and healthy device usage

-

How to set attainable and specific goals

-

Self-awareness techniques and other mental health maintenance strategies (including recognizing both accomplishments and shortcomings)

-

The full scope of effects that come with illicit drug usage

in order to keep young adults healthy, motivated, attentive, and productive.

Digital media has a diminishing effect on our attention, leading many to seek out prescription drugs. Cell phones and digital media applications present us with a wide range of opportunities for innovation and entertainment, but they illustrate the hard truth that not all technological developments are societal advancements.

Chapter Questions

- Multiple Choice: Which brain region is responsible for motivation?

a) Prefrontal cortex

b) Ventral striatum

c) Temporal region

d) Cerebellum

- True or False: Digital media notifications incite the same neurotransmitters in the brain as nicotine, alcohol, and gambling.

- Short Response: Why might people without ADHD feel the effects of prescription stimulants?

references

Bradley, C. (1937). The Behavior Of Children Receiving Benzedrine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 94(3), 577–585. doi: 10.1176/ajp.94.3.577

Elola, J., & Franck, M. (2017, June 25). Smartphone, uma arma de distração em massa. El Pais. Retrieved from https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/06/23/tecnologia/1498217993_075316.html.

Heal, D. J., Smith, S. L., Gosden, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2013). Amphetamine, past and present–a pharmacological and clinical perspective. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 27(6), 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532

Ilieva, I. P., Farah, M. J., & Frontiers Media SA. (2013). Enhancement stimulants: perceived motivational and cognitive advantages. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00198

Lakhan, S. E., & Kirchgessner, A. (2012). Prescription stimulants in individuals with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: misuse, cognitive impact, and adverse effects. Brain and Behavior, 2(5), 661–677. doi: 10.1002/brb3.78

Partridge, B. J., Bell, S. K., Lucke, J. C., Yeates, S., & Hall, W. D. (2011). Smart Drugs “As Common As Coffee”: Media Hype about Neuroenhancement. PLoS ONE, 6(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028416

Ra, C. K., Cho, J., Stone, M. D., Cerda, J. D. L., Goldenson, N. I., Moroney, E., … Leventhal, A. M. (2018). Association of Digital Media Use With Subsequent Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among Adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 320(3), 255. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8931

Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA Network Open, 1(4). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471

images & Media

“Prevalence of Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016” by Wei Bao, MD, PhD, University of Iowa is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Jennings, B. (2013, October 1). Cell Phones, Dopamine, and Development. Retrieved October 8, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kGZvNbfrNag.