Medieval (about 476AD-1600’s)

22

Jonah Vest

The Medieval University

Introduction

Commonly, during the Medieval Era, the European Continent is known for the generalization that is the Dark Ages. It is this time period between 476-1500 AD, or the fall of the Roman Empire to the Early Renaissance, that has been characterized for lacking scientific, scholastic, and societal achievement. However, contrary to popular belief, this time period was all but dark, and is greatly responsible for the ability for this chapter to be written. This time period, this Dark Age, is responsible for the formation of a revolutionary technology that, in modern times, has spread across the globe and led to the dispersion of scholastic knowledge all around the world, The Medieval University. With little resemblance, at its birth with no libraries, laboratories, museums, or buildings of its own, this objectively primitive idea of a Universitas (corporation) is now being renowned for the “great revival of learning” and being referred to by historians as “The renaissance of the twelfth century” (Hannam, 2007; Haskins, 1957, p. 2,4). The framework for this new technology, the university, was so groundbreaking and unorthodox that it shook loose the shackles holding the continent in the Dark Ages, bringing new people and ideas to different parts of the world for the sole purpose to learn and to teach (Haskins, 1957, p. 8). The idea of the University was destined for greatness from humble roots and is now widely recognized as an integral part of science, technology, and society.

Formation of the Medieval Universities

Originally, most of the prevalent universities started as Cathedral schools with higher education bound to those of the clergy or a select group of individuals. Additionally, palace schools were instituted to train young men in the areas of combat as well as theology and language (The Medieval University, 2007). This widespread idea sparked discussion about education and the effects were quickly recognized by national leaders who instituted expansions to the cathedral and palace school’s curriculum. The most notable aspects of this expanse fall under two terms: the Trivium and the Quadrivium. The Trivium refers to grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic, whereas The Quadrivium refers to music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy (The Medieval University, 2007). As knowledge expanded, so did the number of students. This meant that teachers were needed by the cathedral schools in order to attract fee-paying students. This ultimately resulted in the shift of power away from the Church and into the hands of the teachers. This led to the formation of the primitive university or academic guilds. “The vital concept was that a corporation had a distinct legal personality separate from its members that allowed them to show a single face to the outside world while independently being able to govern the workings of the corporation from within.” (Hannam, 2007). Two of the earliest “universities” were The University of Bologna and its sister institution The University of Salerno. The two are documented as two of the earliest educational establishments in history popping into view during the mid-twelfth century. It is important to note that many of the early universities did not have a fixed date and instead grew over time into relevance (The Medieval University, 2007). The University of Paris was next to appear on the map, and with it an established, chosen, date of origin, 1200. Oxford and Cambridge Universities appeared almost in tandem, both emerging during the late twelfth century. Of course, there are dozens of other universities that emerged during this time period, and this is not an exhaustive list of such. These four universities serve as the Founding Fathers of the Modern University.

Abelard

One of the forefathers of the Medieval University is known by one name, Abelard. Abelard was born in 1079 and died in 1142 after an exhaustingly long and triumphant career as an intellectual activist. Historians consider him to be the founder of The University of Paris (Compayre, 1893, p.3). His academic origins begin around 1100 at the, now, University of Notre Dame where he studied as a pupil in an episcopal school. (Note: An episcopal school is similar to a cathedral school in that it was created by the church to serve as a theology-first academic school) After obtaining his master’s degree, Abelard left the monastic structure of education and sought to create his own schools in which philosophical freedom was the center focus, assisting the goal of expanding intellectual conversation. Abelard was known to have a “rare” talent for instruction, a passion for controversy, and a great taste for intellectual study (Compayre, 1893, p. 4). It was this foundation that attracted such a following to Abelard and his lectures. He taught without censorship and conforming to the theological ideas of the church. This rebellious approach stimulated the minds of those pursuing academic careers and aroused the thoughts of philosophy in the public eye so much so that he attracted crowds to his lectures, of three thousand plus students (Compayre, 1893, p. 6-10). However, it was this popularity that ultimately resulted in rivals rising against him and causing his imprisonment by St. Medard for speaking out against theological norms. Upon being released from prison in 1120, he retreated in solitude to an oratory on field land given to him under King Louis the Fat to study and recuperate his intellectual foundation. Unfortunately for Abelard’s solitude, but very fortunately for the success of the modern university, ambitious students located him and flocked to his oratory. So many students came to him to learn from him and created a new school, Paraclete, that he taught at for 3 years (Compayre, 1893, p. 10-15). This goes to show that the foundation and method to which Abelard taught was revolutionary and broke the bounds on intellectual expansion during the Middle Ages. The provocation of the theological norms of education by Abelard, and the unfailing ambition to advocate for intellectual freedom are largely accountable for the separation of theology and philosophy, which ultimately led to the establishment of the modern university.

Shift in Philosophical Norms

During the Middle Ages, the education infrastructure of Europe was largely overseen by the church. This meant that the Church oversaw academic freedom and the boundaries to which subjects were taught. This only lasted for a short time in history; however, because Cathedral schools begun expanding beyond teaching only clergy members, it resulted in the power of education being held by the professors themselves. Cathedral schools needed well-ranked professors to attract students willing to pay the tuition fees (Hannam, 2007). This realization from the professors caused them to leave the Cathedral school, similar to Abelard, and create an instructional manifestation of their own, the Medieval University. It is this missing narrative that is essential to understand how the university came to be.

Conflicts in this manner soon arose between the university and the church centered around the subjects that were acceptable to be taught. The works of famous philosopher, Aristotle, were condemned and deemed heretical by Pierre Tempier at Paris in 1277 and were banned form study because it questioned the faith of Christianity. The battle between Aristotle’s works and the beliefs of Christianity took decades to work out and both sides worked to find common ground in where the beliefs lined up and using science to work out the discrepancies within both (Hannam, 2007). Examples include the finding that Aristotle’s geocentric model was inaccurate, and the biblical flat earth theory could be disproved. These two things opened the floodgates for intellectual expansion in all subjects in search of truth. This was the peak start of the intellectual revolution.

Subjects

During the time of the early university, there were four main areas of study: the Arts, Law, Medicine, and Theology.

The Arts was very different than the arts courses and fields we know today and the words literal meaning. During the Middle Ages, the arts was referred to as the study of logic and natural philosophy. More simply, this meant studying how the inner workings of the universe worked, specifically: the study of physics, motion, time, space, celestial bodies, theological theory, and biology (Daly, 1961, p. 78). Of course, this is not an exhaustive list, but serves as a basis of the field. Commonly studied in this field were the works of Aristotle, as a basis of understanding and to hold new discovery to.

Law was be separated into two categories: Civil Law, and Canon Law. In the Middle Ages civil law was more of a historical study of, not European law, but that of Rome. The basis of all instruction was the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian (Haskins, 1957, p.35-36). The subject was taught to mastery of the entire system of law developed by the romans, and to expand that system into the inner-workings of the European law system. Canon law was sought after more by the church during the Middle Ages. The focus of canonical law is to serve the church regarding law. It implemented the basic ideas of civil law and fabricated new ideas according to the church and ecclesiastical study. The medieval church needed lawyers to run it, and canonists had a good chance of rising to high dignity (Haskins, 1957, p. 36-37).

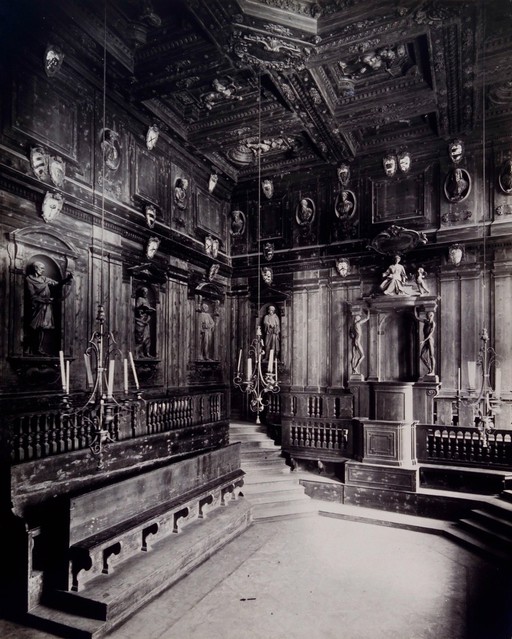

Medicine was a very underdeveloped subject in the medieval university. Aside from prevailing universities like Bologna, there were very few, if any at all, anatomical theaters in practice (Haskins, 1957, p.34-35). This was partially due to the control of human dissection by the church. Most medical knowledge was from books, those of Avicenna, and not on significant medicinal practice.

Picture: The Anatomy Theatre at Bologna University

Theology was, contrary to common thought, the smallest of the subjects pursued at the university. This is largely because admission requirements for theological studies were very high, the time to complete the degree was much longer, and the books needed were very costly.

Though these were the major subject taught in the medieval university, these subjects often spanned a multitude of years and branched into several different topics under the main subject. It is evident, however, that the main areas of study in the modern university took note from the medieval in shaping the way education is taught today.

Student Life

Student life in the medieval university was much different than the perception of the modern. The university itself was the professor and the lessons he taught rather than a place, however as the decades and centuries passed, the rise of the modern university layout can be largely attributed to the students. (Note: Notice the pronoun “he” is the previous statement. This is because under the canonical law of the time, women were prohibited from being admitted to universities.) As there were no dedicated university buildings at the time, life as a student was quite migratory. Students required housing and this meant the townspeople of the place of which the professor was in, were the obvious choice. The townspeople rented out their rooms and necessaries to students. Because the students put extra money in the pockets of the townspeople, as the price of these necessities rose, students threatened to migrate away from the town and to another with better cost of living; thus, it is better to rent one’s rooms for less than not at all (Haskins, 1957, p. 8-9). By the mid-eleventh century, hundreds of students were brought from far “beyond the alps” and wide of Italy to the universities, which now were concreting themselves in the streets of the town (Haskins, 1957, p. 8). Another interesting aspect of the modern university that has its roots in the Middle Ages is the college. Originally this was termed as merely a hall of residence. The goal of such was a place of guaranteed housing for students that didn’t rely on the townspeople (Haskins, 1957, p.18-19). Over time, the college involved itself in the university through major involvement in student life and eventually became a large part of it. The students did not just begin the collegiate rooming system, but also the format in which the lectures were taught.

Statutes began to be written that applied to professors. Some examples include: a professor may not be absent without leave or be fined, the lecture must begin with the bell and finish within one minute of the next bell, and he must cover every chapter in full or be fined (Haskins, 1957, p. 10). These statutes show a shift in power from the professor to the students because the professor only made as much money as the students attracted and sincerity of his teaching.

As for tuition, it wasn’t much different than the things the modern university students must spend money on, the major different is the relatively primitive forms of such expenses. Student tuition was divided into two major categories: living expenses and tuition. Living expenses included many things such as room and board, clothing, bedding, lighting, medical and travel. Tuition mainly included the cost of books, lecture fees, and other academic fees. Living expenses were the larger source of tuition in the medieval university. “The British scholar Alan Cobban assumed this to be the amount an ordinary self-supporting student in the fifteenth century would spend on basic food and drink. Thus, the annual expenses of ordinary self-supporting university student for food and drink would be approximately 1 pound, 1 shilling.”. This accounted for the bare minimum dietary need of the average student. The cost of rent could range, depending on the university, from 6 shillings all the way up to 20 shillings annually (Shanwei, 2017). Lecture fees made up the majority of academic tuition fees. These fees differed widely depending on the university. Lecture fees were generally higher for Italian universities and were comparatively lower at universities in other regions. On the lower end at Oxford University some students paid less than one gold florin per term. On the higher end, some students at University of Bologna were required over 10 gold florins per term. On average students paid between 48 and 250 gold florins (about 26-138 USD), depending on the region, for a four-year university education (Shanwei, 2017).

Impact On STS

Through a historical lens, the Middle Ages are portrayed as a dark age of little scientific, technological, and societal significance; however, the Middle Ages made great leaps in the realm of academia and set the foundation for the scientific expansion, modern university, and academic society existing today.

The expansion of scientific knowledge has important roots in the Middle Age. As shown earlier in the chapter, the existence of Abelard, shift of power away from the cathedral school, and advocacy by students significantly broadened the pathway for science to enter commonplace within the world and allow for the freedom of thought and discovery.

Most notably from this historical data, one of the most important technologies to ever be created by humans, is the fruit of this era, the technology that is The University. From its humble beginnings in the Middle Ages, the medieval university ambitiously developed from a system ruled and privatized by the church for the church, to a professor traveling in search of students to teach, students traveling far and wide to hear professors teach, the first buildings and theatres being built under a university name, full established communities under one name, The University. A technology that is now so advanced there are over 25,000 in existence across the globe, each founded on the principle of intellectual discovery and mastery, and each tracing its roots back to its seed, the Medieval University.

In the study of STS, one of the viewpoints of study is how science and technology impact society. The medieval university not only accelerated the expansion of scientific knowledge, but also enormously impacted the way in which society worked in the Middle Ages and today. One of the ways in which the medieval university affected society was slow but served as training wheels to get the European continent back on its feet from a “dark period” of economic slumber. As the university became more popular, there was an increase in need for rooms for the students. As mentioned earlier, the townspeople rented out rooms and received money in exchange. This got the economic gears of the continent turning. Another big way the university helped the economy was through the need of manuscripts and books being made. Historical evidence shows that manuscript production skyrocketed during the Middle Ages from less than 100,000 manuscripts per century to over 4 million (Cantoni & Yuchtman, 2012). The medieval universities also increased the amount of human capital in society. This was useful because it provided the framework for the Commercial revolution that took place at the same time as the creation of the university. A broad claim by Harold Berman, quoted in Medieval Universities, Legal Institutions, and the Commercial Revolution suggests, “The increasing application of Roman and canon law across all spheres of public life could have had a series of positive effects on economic development. … Harold Berman, who suggested that their discovery of Roman law, and the increasing development and sophistication of European legal systems (canon, Roman, and merchant law), brought a new approach to the solution of conflicts between secular and religious authorities which had plagued Europe during the better part of the Middle Ages.”. This claim is supported by the historical evidence that the need for commercial materials by the medieval universities, increased the economic wellbeing of the European continent, thus, improving the quality of life in society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Medieval University is a keystone piece of intellectual history stemming from the Middle Ages. As a technology, the university provided the necessary means for intellectual expansion and economic awakening in the European continent during this time and is the direct predecessor of the modern university that has spread across the world today.

References

Bologna, E. (2019). Archiginnasio, Bologna: the anatomy theatre. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://www.europeana.eu/en/item/9200579/tpe4dud3.

Cantoni, D., & Yuchtman, N. (2014). Medieval universities, legal institutions, and the commercial revolution. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(2), 823–887. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju007

Compayre, G. (1893). Abelard and the origin and early history of the Universities. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Daly, L. J. (1961). The medieval university, 1200-1400. Sheed and Ward.

Hannam, J. (2007). Medieval science and philosophy. Science and Church in the Middle Ages. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://jameshannam.com/medievalscience.htm.

Haskins, C. H. (1957). Rise of universities. Great Seals Books: A Division of Cornell University Press.

Shanwei, X. (2017). Study of the tuition and living expenses of medieval European university students. Clemson University libraries – login. Retrieved September 26, 2021, from https://web-a-ebscohost-com.libproxy.clemson.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=807473ca-6470-422e-8246-8c8d78adaa19%40sessionmgr4006&bdata=#AN=120631646&db=aph.

University of Delaware. (2007). The medieval University. British Literature Wiki. Retrieved September 26, 2021, fxfrom https://sites.udel.edu/britlitwiki/the-medieval-university/.