5

Dr. Senta German; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Beth Harris; British Museum; Iselin Claire and André-Salvini Béatrice; and Dr. Jeffrey Becker

In this chapter

Sumerian

- Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization

- Sumer, an introduction

- White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk

- Warka Vase

- Standing Male Worshipper (Tell Asmar)

- Cylinder Seals

- Standard of Ur and other objects from the royal graves

Akkadian

Neo-Sumerian

Babylonian & Neo-Babylonian

- Babylonia, an introduction

- Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi

- The Ishtar Gate and Neo-Babylonian art and architecture

Assyria

Persia

Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization

Home to some of the earliest and greatest empires, the Near East is often referred to as the cradle of civilization.

The cradle of civilization

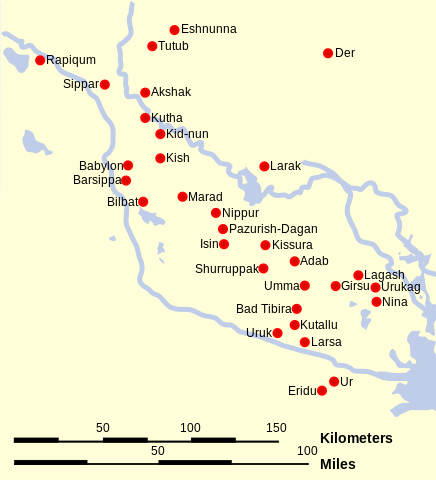

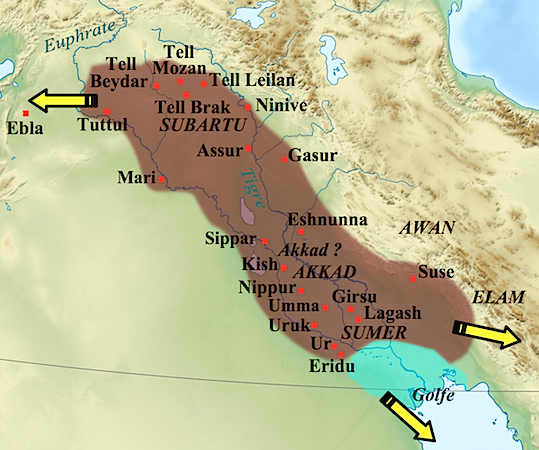

Some of the earliest complex urban centers can be found in Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (early cities also arose in the Indus Valley and ancient China). The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

What’s in a name?

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed “the near east.” Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn’t have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West’s interests in the Biblical “Holy Land” that ancient Near Eastern materials have been be regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art. An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French 19th century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were discovered and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The excavations inspired The Nineveh Court at the 1851 World’s Fair in London and a style of decorative art and architecture called Assyrian Revival. Ancient Near Eastern art remains popular today; in 2007 a 2.25 inch high, early 3rd millennium limestone sculpture, the Guennol Lioness, was sold for 57.2 million dollars, the second most expensive piece of sculpture sold at that time.

A complex history

The history of the Ancient Near East is complex and the names of rulers and locations are often difficult to read, pronounce and spell. Moreover, this is a part of the world which today remains remote from the West culturally while political tensions have impeded mutual understanding. However, once you get a handle on the general geography of the area and its history, the art reveals itself as uniquely beautiful, intimate and fascinating in its complexity.

Geography and the growth of cities

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

The region lacks stone (for building), precious metals and timber. Historically, it has relied on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture. Here, for the first time, thanks to ample food and a strong administrative class, the West develops a very high level of craft specialization and artistic production.

Sumer, an introduction

Sumer was home to some of the oldest known cities, supported by a focus on agriculture.

The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is in Sumer that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk.

Uruk

Prehistory ends with Uruk, where we find some of the earliest written records. This large city-state (and its environs) was largely dedicated to agriculture and eventually dominated southern Mesopotamia. Uruk perfected Mesopotamian irrigation and administration systems.

An agricultural theocracy

Within the city of Uruk, there was a large temple complex dedicated to Innana, the patron goddess of the city. The City-State’s agricultural production would be “given” to her and stored at her temple. Harvested crops would then be processed (grain ground into flour, barley fermented into beer) and given back to the citizens of Uruk in equal share at regular intervals. The head of the temple administration, the chief priest of Innana, also served as political leader, making Uruk the first known theocracy. We know many details about this theocratic administration because the Sumerians left numerous documents in the form of tablets written in cuneiform script.

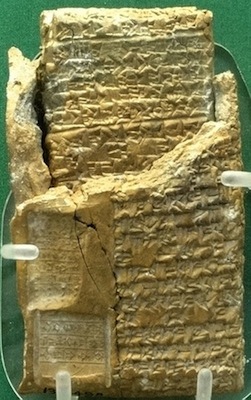

It is almost impossible to imagine a time before writing. However, you might be disappointed to learn that writing was not invented to record stories, poetry, or prayers to a god. The first fully developed written script, cuneiform, was invented to account for something unglamorous, but very important—surplus commodities: bushels of barley, head of cattle, and jars of oil!

The origin of written language (c. 3200 B.C.E.) was born out of economic necessity and was a tool of the theocratic (priestly) ruling elite who needed to keep track of the agricultural wealth of the city-states. The last known document written in the cuneiform script dates to the first century C.E. Only the hieroglyphic script of the Ancient Egyptians lasted longer.

A reed and clay tablet

A single reed, cleanly cut from the banks of the Euphrates or Tigris river, when pressed cut-edge down into a soft clay tablet, will make a wedge shape. The arrangement of multiple wedge shapes (as few as two and as many as ten) created cuneiform characters. Characters could be written either horizontally or vertically, although a horizontal arrangement was more widely used.

Very few cuneiform signs have only one meaning; most have as many as four. Cuneiform signs could represent a whole word or an idea or a number. Most frequently though, they represented a syllable. A cuneiform syllable could be a vowel alone, a consonant plus a vowel, a vowel plus a consonant and even a consonant plus a vowel plus a consonant. There isn’t a sound that a human mouth can make that this script can’t record.

Probably because of this extraordinary flexibility, the range of languages that were written with cuneiform across history of the Ancient Near East is vast and includes Sumerian, Akkadian, Amorite, Hurrian, Urartian, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hatian and Elamite.

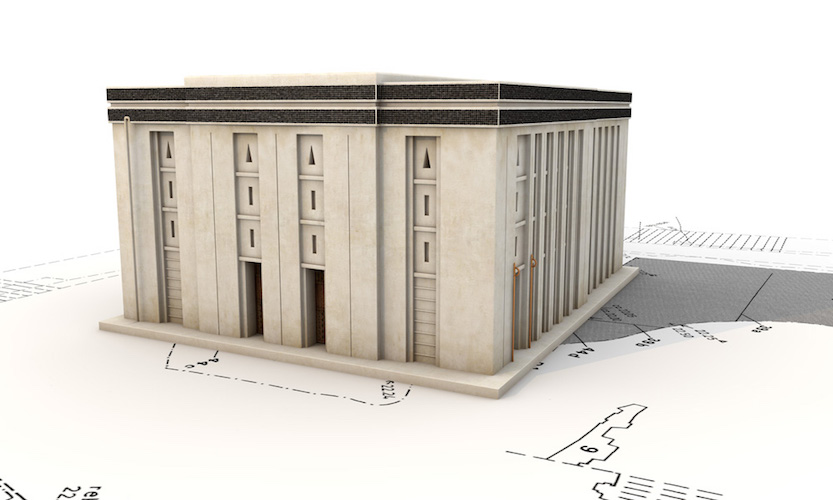

White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk

A gleaming temple built atop a mud-brick platform, it towered above the flat plain of Uruk.

Visible from a great distance

Uruk (modern Warka in Iraq)—where city life began more than five thousand years ago and where the first writing emerged—was clearly one of the most important places in southern Mesopotamia. Within Uruk, the greatest monument was the Anu Ziggurat on which the White Temple was built. Dating to the late 4th millennium B.C.E. (the Late Uruk Period, or Uruk III) and dedicated to the sky god Anu, this temple would have towered well above (approximately 40 feet) the flat plain of Uruk, and been visible from a great distance—even over the defensive walls of the city. ZigguratsA ziggurat is a built raised platform with four sloping sides—like a chopped-off pyramid. Ziggurats are made of mud-bricks—the building material of choice in the Near East, as stone is rare. Ziggurats were not only a visual focal point of the city, they were a symbolic one, as well—they were at the heart of the theocratic political system (a theocracy is a type of government where a god is recognized as the ruler, and the state officials operate on the god’s behalf). So, seeing the ziggurat towering above the city, one made a visual connection to the god or goddess honored there, but also recognized that deity’s political authority.

Excavators of the White Temple estimate that it would have taken 1500 laborers working on average ten hours per day for about five years to build the last major revetment (stone facing) of its massive underlying terrace (the open areas surrounding the White Temple at the top of the ziggurat). Although religious belief may have inspired participation in such a project, no doubt some sort of force (corvée labor—unpaid labor coerced by the state/slavery) was involved as well.

The sides of the ziggurat were very broad and sloping but broken up by recessed stripes or bands from top to bottom (see digital reconstruction, above), which would have made a stunning pattern in morning or afternoon sunlight. The only way up to the top of the ziggurat was via a steep stairway that led to a ramp that wrapped around the north end of the Ziggurat and brought one to the temple entrance. The flat top of the ziggurat was coated with bitumen (asphalt—a tar or pitch-like material similar to what is used for road paving) and overlaid with brick, for a firm and waterproof foundation for the White temple. The temple gets its name for the fact that it was entirely white washed inside and out, which would have given it a dazzling brightness in strong sunlight.

The White Temple

The White temple was rectangular, measuring 17.5 x 22.3 meters and, at its corners, oriented to the cardinal points. It is a typical Uruk “high temple (Hochtempel)” type with a tri-partite plan: a long rectangular central hall with rooms on either side (plan). The White Temple had three entrances, none of which faced the ziggurat ramp directly. Visitors would have needed to walk around the temple, appreciating its bright façade and the powerful view, and likely gained access to the interior in a “bent axis” approach (where one would have to turn 90 degrees to face the altar), a typical arrangement for Ancient Near Eastern temples.

The north west and east corner chambers of the building contained staircases (unfinished in the case of the one at the north end). Chambers in the middle of the northeast room suite appear to have been equipped with wooden shelves in the walls and displayed cavities for setting in pivot stones which might imply a solid door was fitted in these spaces. The north end of the central hall had a podium accessible by means of a small staircase and an altar with a fire-stained surface. Very few objects were found inside the White Temple, although what has been found is very interesting. Archaeologists uncovered some 19 tablets of gypsum on the floor of the temple—all of which had cylinder seal impressions and reflected temple accounting. Also, archaeologists uncovered a foundation deposit of the bones of a leopard and a lion in the eastern corner of the Temple (foundation deposits, ritually buried objects and bones, are not uncommon in ancient architecture).

To the north of the White Temple there was a broad flat terrace, at the center of which archaeologists found a huge pit with traces of fire (2.2 x 2.7m) and a loop cut from a massive boulder. Most interestingly, a system of shallow bitumen-coated conduits were discovered. These ran from the southeast and southwest of the terrace edges and entered the temple through the southeast and southwest doors. Archaeologists conjecture that liquids would have flowed from the terrace to collect in a pit in the center hall of the temple.

Warka Vase

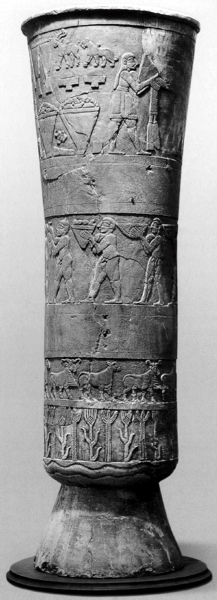

One of the most precious artifacts from Sumer, the Warka Vase was looted and almost lost forever.

Picturing the ruler

So many important innovations and inventions emerged in the Ancient Near East during the Uruk period (c. 4000 to 3000 B.C.E. and named after the Sumerian city of Uruk). One of these was the use of art to illustrate the role of the ruler and his place in society. The Warka Vase, c. 3000 B.C.E., was discovered at Uruk (Warka is the modern name, Uruk the ancient name), and is probably the most famous example of this innovation. In its decoration we find an example of the cosmology of ancient Mesopotamia.

The vase, made of alabaster and standing over three feet high (just about a meter) and weighing some 600 pounds (about 270 kg), was discovered in 1934 by German excavators working at Uruk in a ritual deposit (a burial undertaken as part of a ritual) in the temple of Inanna, the goddess of love, fertility, and war and the main patron of the city of Uruk. It was one of a pair of vases found in the Inanna temple complex (but the only one on which the image was still legible) together with other valuable objects.

Given the significant size of the Warka Vase, where it was found, the precious material from which it is carved and the complexity of its relief decoration, it was clearly of monumental importance, something to be admired and valued. Though known since its excavation as the Warka “Vase,” that term does little to express the sacredness of this object for the people who lived in Uruk five thousand years ago.

The relief carvings on the exterior of the vase run around its circumference in four parallel bands (or registers, as art historians like to call them) and develop in complexity from the bottom to the top.

Beginning at the bottom, we see a pair of wavy lines from which grow neatly alternating plants that appear to be grain (probably barley) and reeds, the two most important agricultural harvests of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia. There is a satisfying rhythm to this alternation, and one that is echoed in the rhythm of the rams and ewes (male and female sheep) that alternate in the band above this. The sheep march to the right in tight formation, as if being herded—the method of tending this important livestock in the agrarian economy of the Uruk period.

The band above the sheep is a blank and might have featured painted decoration that has since faded away. Above this blank band, a group of nine identical men march to the left. Each holds a vessel in front of his face, and which appear to contain the products of the Mesopotamian agricultural system: fruits, grains, wine, and mead. The men are all naked and muscular and, like the sheep beneath them, are closely and evenly grouped, creating a sense of rhythmic activity. Nude figures in Ancient Near Eastern art are meant to be understood as humble and low status, so we can assume that these men are servants or slaves (the band above displays the slave owners).

The top band of the vase is the largest, most complex, and least straightforward. It has suffered some damage but enough remains that the scene can be read. The center of the scene appears to depict a man and a woman who face each other. A smaller naked male stands between them holding a container of what looks like agricultural produce which he offers to the woman. The woman, identified as such by her robe and long hair, at one point had an elaborate crown on her head (this piece was broken off and repaired in antiquity).

Behind her are two reed bundles, symbols of the goddess Inanna, whom, it is assumed, the woman represents. The man she faces is nearly entirely broken off, and we are left with only the bottom of his long garment. However, men with similar robes are often found in contemporary seal stone engraving and based upon these, we can reconstruct him as a king with a long skirt, a beard and a head band. The tassels of his skirt are held by another smaller scaled man behind him, a steward or attendant to the king, who wears a short skirt.

The rest of the scene is found behind the reed bundles at the back of Inanna. There we find two horned and bearded rams (one directly behind the other, so the fact that there are two can only be seen by looking at the hooves) carrying platforms on their backs on which statues stand. The statue on the left carries the cuneiform sign for EN, the Sumerian word for chief priest. The statue on the right stands before yet another Inanna reed bundle. Behind the rams is an array of tribute gifts including two large vases which look quite a lot like the Warka Vase itself.

What could this busy scene mean? The simplest way to interpret it is that a king (presumably of Uruk) is celebrating Inanna, the city’s most important divine patron. A more detailed reading of the scene suggests a sacred marriage between the king, acting as the chief priest of the temple, and the goddess—each represented in person as well as in statues. Their union would guarantee for Uruk the agricultural abundance we see depicted behind the rams. The worship of Inanna by the king of Uruk dominates the decoration of the vase. The top illustrates how the cultic duties of the Mesopotamian king as chief priest of the goddess, put him in a position to be responsible for and proprietor of, the agricultural wealth of the city state.

Backstory

The Warka Vase, one of the most important objects in the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, was stolen in April 2003 with thousands of other priceless ancient artifacts when the museum was looted in the immediate aftermath of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Warka Vase was returned in June of that same year after an amnesty program was created to encourage the return of looted items. The Guardian reported that “The United States army ignored warnings from its own civilian advisers that could have stopped the looting of priceless artifacts in Baghdad….”

Even before the invasion, looting was a growing problem, due to economic uncertainty and widespread unemployment in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War. According to Dr. Neil Brodie, Senior Research Fellow on the Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa project at the University of Oxford, “In the aftermath of that war…as the country descended into chaos, between 1991 and 1994 eleven regional museums were broken into and approximately 3,000 artifacts and 484 manuscripts were stolen….” The vast majority of these have not been returned. And, as Dr. Brodie notes, the most important question may be why no concerted international action was taken to block the sale of objects looted from archaeological sites and cultural institutions during wartime.

Read more about endangered cultural heritage in the Near East in Smarthistory’s ARCHES (At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series) section.

Standing Male Worshipper (Tell Asmar)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

One of a group buried in a temple almost 5,000 years ago, this statue’s job was to worship Abu—forever. This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Watch the video at https://youtu.be/DKMWS9qJ_1U.

Steven: Almost 5,000 years ago somebody carefully buried a small group of alabaster figure in the floor of a temple.

Beth: And we’re looking at one of those figures now. The Metropolitan Museum of Art calls this a standing male worshipper. He was buried along with 11 other figures for a total of 12, most of them male. Steven: We’re looking at one of the smaller figures. They range from just under a foot to almost three feet. Beth: The temple where these were buried was in a city called Eshnunna in the northern part of ancient Mesopotamia.Steven: What is now called Tell Asmar. The figures from Tell Asmar are widely considered to be the great expression of early dynastic Sumerian art. And we think the temple was dedicated to the god Abu.

Beth: At this time, the third millennium B.C.E., in this area around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, some of the earliest cities in the world emerged and writing emerged. This is a watershed in human history. The cities had administrative buildings, temples, palaces, many of which have been unearthed by archeologists.

Steven: This is the transitional period right after the Bronze Age, the tail end of the Neolithic, when civilizations are founded in the great river valleys around the world. And he’s adorable.

Beth: He is adorable. His wide eyes and his sense of attentiveness are very appealing I think but of course, he wasn’t meant to be looking at us. He was meant to be attentive to a statue, a sculpture of a god who was believed to be embodied in the sculpture.

Steven: In fact, we believe that the person for whom this was a kind of stand-in was also embodied in this figurine.

Beth: So an elite member of ancient Sumerian culture paid to have this sculpture made and placed before the god to be a kind of stand-in to perhaps continually owner prayers, to be continually attentive to the god.

Steven: His hands are clasped together, he stands erect, his shoulders are broad so there is a sense of frontality.

Beth: Even though he is carved on both sides he was meant to be seen from the front. Although that term “meant to be seen” is a funny one.

Steven: Well he was meant to be seen by a God. You can see that the hair is parted at the center of the scalp and comes down in wavelets or perhaps braids that spiral down and then frame the central beard which is quite formal and cascades down in a series of regular waves. His hands are clasped just below the beard. His shoulders are really broad, his upper arms very broad and then there’s very fine incising at the bottom of his skirt.

Beth: But it’s odd to me how cylindrical the bottom part of his body is and how flattened out the torso is.

Steven: If you look at the face carefully, you can see that the very large eyes are in fact inlaid shell and in the center, the pupils are black limestone. And you can also see that there is an incising of the eyebrows that might have originally been inlaid as well.

Beth: This is really different from Egyptian culture which emerges at the same time. In Egyptian culture, the sculptures primarily represent the pharaoh—the king—and indicate his divinity, but in the ancient Near East, we have these votive images of worshippers but not so much of the kings, at least during this early dynastic period. The figures at Tell Asmar that were unearthed are very similar. They’re not meant to be portraits of a specific person but a symbol of that person.

Steven: But he does look very humble, his mouth is closed, his lips are sealed together and of course he is wonderfully attentive. Beth: And the fact that his hands are clasped I think makes him seem more humble as well.

Steven: There are some interesting subtle choices that whoever carved this made. Look at the way that the skirt extends out and attaches itself to the forearms a bit wider than we would expect.

Beth: And the torso, it’s just this almost V-shape. There is a sense of geometric patterning here and not the naturalistic forms of the body.

Steven: If you look at the back of the figure you can see that there is a little cleft that’s been carved in horizontally. And there’s also what seems to be the indication perhaps of a tied belt that hangs down.

Beth: You understand, I think, the artist’s decision not to make a naturalistic figure because a naturalistic figure before the god might give a sense of someone just visiting, just passing through, but this idea of a static, symmetrical, frontal, wide-eyed figure gives a sense of timelessness of a figure that is forever offering prayers to the god.

Cylinder seals

Cuneiform was used for official accounting, governmental and theological pronouncements and a wide range of correspondence. Nearly all of these documents required a formal “signature,” the impression of a cylinder seal.

Signed with a cylinder seal

A cylinder seal is a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse (intaglio) and hung on strings of fiber or leather. These often beautiful objects were ubiquitous in the Ancient Near East and remain a unique record of individuals from this era. Each seal was owned by one person and was used and held by them in particularly intimate ways, such as strung on a necklace or bracelet.

When a signature was required, the seal was taken out and rolled on the pliable clay document, leaving behind the positive impression of the reverse images carved into it. However, some seals were valued not for the impression they made, but instead, for the magic they were thought to possess or for their beauty.

The first use of cylinder seals in the Ancient Near East dates to earlier than the invention of cuneiform, to the Late Neolithic period (7600–6000 B.C.E.) in Syria. However, what is most remarkable about cylinder seals is their scale and the beauty of the semi-precious stones from which they were carved. The images and inscriptions on these stones can be measured in millimeters and feature incredible detail.

The stones from which the cylinder seals were carved include agate, chalcedony, lapis lazuli, steatite, limestone, marble, quartz, serpentine, hematite and jasper; for the most distinguished there were seals of gold and silver. To study Ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals is to enter a uniquely beautiful, personal and detailed miniature universe of the remote past, but one which was directly connected to a vast array of individual actions, both mundane and momentous.

Why cylinder seals are interesting

Art historians are particularly interested in cylinder seals for at least two reasons. First, it is believed that the images carved on seals accurately reflect the pervading artistic styles of the day and the particular region of their use. In other words, each seal is a small time capsule of what sorts of motifs and styles were popular during the lifetime of the owner. These seals, which survive in great numbers, offer important information to understand the developing artistic styles of the Ancient Near East.

The second reason why art historians are interested in cylinder seals is because of the iconography (the study of the content of a work of art). Each character, gesture and decorative element can be “read” and reflected back on the owner of the seal, revealing his or her social rank and even sometimes the name of the owner. Although the same iconography found on seals can be found on carved stelae, terra cotta plaques, wall reliefs and paintings, its most complete compendium exists on the thousands of seals which have survived from antiquity.

Standard of Ur and other objects from the Royal Graves

At the center of Ur, a rubbish dump grew over the centuries—it evolved into a cemetery for the elite.

The city of Ur

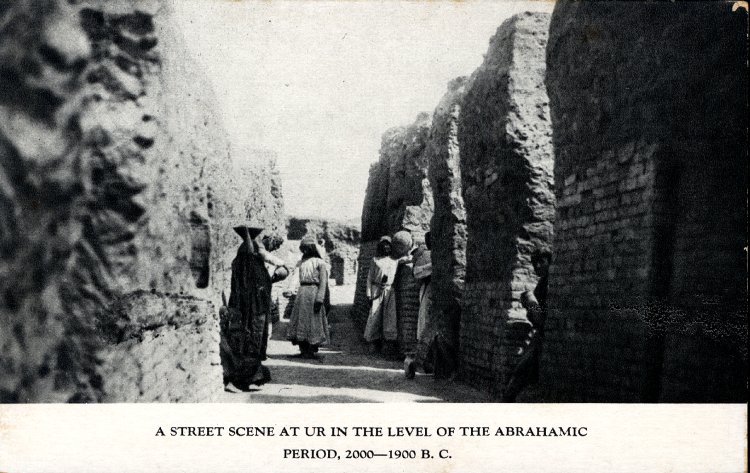

Known today as Tell el-Muqayyar, the “Mound of Pitch,” the site was occupied from around 5000 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E. Although Ur is famous as the home of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham (Genesis 11:29-32), there is no actual proof that Tell el-Muqayyar was identical with “Ur of the Chaldees.” In antiquity the city was known as Urim.

The main excavations at Ur were undertaken from 1922-34 by a joint expedition of The British Museum and the University Museum, Pennsylvania, led by Leonard Woolley. At the center of the settlement were mud brick temples dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.E. At the edge of the sacred area a cemetery grew up which included burials known today as the Royal Graves. An area of ordinary people’s houses was excavated in which a number of street corners have small shrines. But the largest surviving religious buildings, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, also include one of the best preserved ziggurats, and were founded in the period 2100-1800 B.C.E. For some of this time Ur was the capital of an empire stretching across southern Mesopotamia. Rulers of the later Kassite and Neo-Babylonian empires continued to build and rebuild at Ur. Changes in both the flow of the River Euphrates (now some ten miles to the east) and trade routes led to the eventual abandonment of the site.

The royal graves of Ur

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, sat a rubbish dump built up over centuries. Unable to use the area for building, the people of Ur started to bury their dead there. The cemetery was used between about 2600-2000 B.C.E. and hundreds of burials were made in pits. Many of these contained very rich materials.

In one area of the cemetery a group of sixteen graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The most complete tomb discovered belonged to a lady identified as Pu-abi from the name carved on a cylinder seal found with the burial.

The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to seventy-four such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

The Standard of Ur

This object was found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above the right shoulder of a man. Its original function is not yet understood.

Leonard Woolley, the excavator at Ur, imagined that it was carried on a pole as a standard, hence its common name. Another theory suggests that it formed the soundbox of a musical instrument.

When found, the original wooden frame for the mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli had decayed, and the two main panels had been crushed together by the weight of the soil. The bitumen acting as glue had disintegrated and the end panels were broken. As a result, the present restoration is only a best guess as to how it originally appeared.

The main panels are known as “War” and “Peace.” “War” shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army. Chariots, each pulled by four donkeys, trample enemies; infantry with cloaks carry spears; enemy soldiers are killed with axes, others are paraded naked and presented to the king who holds a spear.

The “Peace” panel depicts animals, fish and other goods brought in procession to a banquet. Seated figures, wearing woolen fleeces or fringed skirts, drink to the accompaniment of a musician playing a lyre. Banquet scenes such as this are common on cylinder seals of the period, such as on the seal of the “Queen” Pu-abi, also in the British Museum (see image above).

Queen’s Lyre

Leonard Woolley discovered several lyres in the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. This was one of two that he found in the grave of “Queen” Pu-abi. Along with the lyre, which stood against the pit wall, were the bodies of ten women with fine jewelry, presumed to be sacrificial victims, and numerous stone and metal vessels. One woman lay right against the lyre and, according to Woolley, the bones of her hands were placed where the strings would have been.

The wooden parts of the lyre had decayed in the soil, but Woolley poured plaster of Paris into the depression left by the vanished wood and so preserved the decoration in place. The front panels are made of lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone originally set in bitumen. The gold mask of the bull decorating the front of the sounding box had been crushed and had to be restored. While the horns are modern, the beard, hair and eyes are original and made of lapis lazuli.

This musical instrument was originally reconstructed as part of a unique “harp-lyre,” together with a harp from the burial, now also in The British Museum. Later research showed that this was a mistake. A new reconstruction, based on excavation photographs, was made in 1971-72.

Akkad, an introduction

Founded by the famed Sargon the Great, Akkad was a powerful military empire.

Akkad

Competition between Akkad in the north and Ur in the south created two centralized regional powers at the end of the third millennium (c. 2334–2193 B.C.E.).

This centralization was military in nature and the art of this period generally became more martial. The Akkadian Empire was begun by Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad (Akkad has not yet been located, though one theory puts it under modern Baghdad).

Head of an Akkadian Ruler

This image of an unidentified Akkadian ruler (some say it is Sargon, but no one knows) is one of the most beautiful and terrifying images in all of Ancient Near Eastern art. The life-sized bronze head shows in sharp geometric clarity, locks of hair, curled lips and a wrinkled brow. Perhaps more awesome than the powerful and somber face of this ruler is the violent attack that mutilated it in antiquity.

Ur

The kingdom of Akkad ends with internal strife and invasion by the Gutians from the Zagros mountains to the northeast. The Gutians were ousted in turn and the city of Ur, south of Uruk, became dominant. King Ur-Nammu established the third dynasty of Ur, also referred to as the Ur III period.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Naram-Sin leads his victorious army up a mountain, as vanquished Lullubi people fall before him.

Watch the video of Dr. Harris and Dr. Zucker’s conversation: https://youtu.be/OY79AuGZDNI

This monument depicts the Akkadian victory over the Lullubi Mountain people. In the 12th century B.C.E., a thousand years after it was originally made, the Elamite king, Shutruk-Nahhunte, attacked Babylon and, according to his later inscription, the stele was taken to Susa in what is now Iran. A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or relief carving.

Headless statue of Gudea, prince of Lagash

By Iselin Claire and André-Salvini Béatrice, Louvre Museum

Gudea commissioned a large number of statues made of hard diorite showing himself standing or sitting in front of the gods of Lagash, whose temples he built or restored. This statue, known as “The architect with a plan,” is consecrated to Ningirsu, the great god of the pantheon of the state of Lagash. It is remarkable in several respects and personifies the prince as the architect of his temple, Eninnu, which probably figures on the plan laid on his knees.

An extremely interesting monument

Gudea is shown life-sized, conventionally seated on a stool with splayed legs joined by two struts supporting the seat. The prince is barefooted, with his hands clasped together as a sign of deference to the god. He is dressed in a long princely cloak with fringed edges, draped over the left arm and tucked under the right, and ending in folds at the neck. Of the many statues dedicated by Gudea, this one is particularly interesting for the quality of the stone and the carving, as well as for the tablet engraved with architect’s drawings laid on the prince’s knees. The tablet also has a stylet and a graduated ruler. An inscription, unique in both length and content, covers almost the entire surface.

The temple-building prince

This statue shows the prince as the architect of the temple dedicated to the supreme god of the pantheon of the state of Lagash. Such personification recalls Ur-Nanshe, the prince of Lagash, who had already been portrayed carrying a hod of bricks on a perforated low relief, now in the Louvre, which dates from the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. The construction of Eninnu temple, consecrated to Ningirsu, was the main enterprise and concern of Gudea’s reign. The plan on the tablet is shown in orthogonal projection and probably depicts the wall around Ningirsu’s shrine. It follows the conventions of Mesopotamian clay and brick architecture: a thick wall reinforced with outer buttresses, pierced by gates fortified with redans, and flanked by towers. The walls surround an elongated, irregular space, devoid of buildings. On the short sides and the outer wall, small structures are placed in recesses.

The graduated ruler is damaged, but we can make out 16 sections, each with gradations from one to six separated by empty spaces.

A royal votive inscription

Gudea has left us the longest known inscriptions in Sumerian, exalting his piety towards the gods according to an ideal that is very different from the Akkadian militarism that had preceded him. The inscription is here divided into 368 compartments arranged in nine columns. It begins on the back and then extends round the sides, covering the entire seat and lower part of Gudea’s robe. The text begins with a list of regular offerings made to the statue of Gudea, as for a cult figure. In fact, it is a “living statue,” intended to replace the prince before his god for eternity and to transmit his messages, in particular the fact that the Eninnu was built according to divine rules and social laws. Gudea’s titles, given after the list of offerings, reveal that all the gods of the pantheon of Lagash have conferred the principality on him, together with the qualities needed to shoulder this responsibility. The account of the construction of the Eninnu lists the foreign countries that supplied the materials, thus revealing the power of Lagash: cedars from Amanus, stones from northern Syria, and booty captured in Elam. Carved according to the rites, the statue is made of diorite, a stone regarded as a noble material, more durable than others, because it is harder to destroy. The statue is given a name and the right to speak, as well as a place on the esplanade of the temple of Ningirsu, under the god’s eye. The inscription ends with a long curse on anyone who might try to desecrate it. Later princes took heed of these words, since the kings of the empire of Ur III honored the memory of Gudea with libations and offerings, as instructed on the statue.

https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/headless-statue-gudea-prince-lagash

Babylonia, an introduction

On the River Euphrates

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi (about 1790-1750 B.C.E.). He established control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria. The British Museum holds one of the iconic artworks of this period, the so-called “Queen of the Night.”From around 1500 B.C.E. a dynasty of Kassite kings took control in Babylon and unified southern Iraq into the kingdom of Babylonia. The Babylonian cities were the centers of great scribal learning and produced writings on divination, astrology, medicine and mathematics. The Kassite kings corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaohs as revealed by cuneiform letters found at Amarna in Egypt, now in the British Museum.

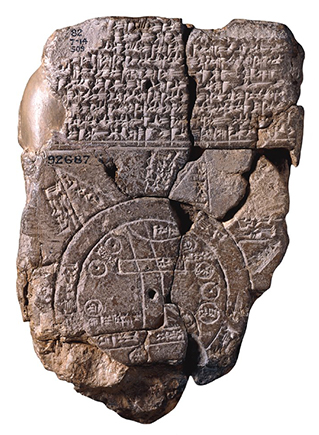

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. Other Babylonian cities also flourished; scribes in the city of Sippar probably produced the famous “Map of the World” (see image below).

Babylonian kings

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. There were two sets of fortified walls and massive palaces and religious buildings, including the central ziggurat tower. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the famous “Hanging Gardens.” However, the last Babylonian king Nabonidus (555-539 B.C.E.) was defeated by Cyrus II of Persia and the country was incorporated into the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire.

New Threats

Babylon remained an important center until the third century B.C.E., when Seleucia-on-the-Tigris was founded about ninety kilometers to the north-east. Under Antiochus I (281-261 B.C.E.) the new settlement became the official Royal City and the civilian population was ordered to move there. Nonetheless a village existed on the old city site until the eleventh century AD. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Since 1958 the Iraq Directorate-General of Antiquities has carried out further investigations. Unfortunately, the earlier levels are inaccessible beneath the high water table. Since 2003, our attention has been drawn to new threats to the archaeology of Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

For two thousand years the myth of Babylon has haunted the European imagination. The Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens, Belshazzar’s Feast and the Fall of Babylon have inspired artists, writers, poets, philosophers and film makers.

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi

Law is at the heart of modern civilization, and is often based on principles listed here nearly 4,000 years ago.

Hammurabi of the city state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets (a stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving). We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi: A CONVERSATION

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Musee du Louvre, Paris. Watch the video: https://youtu.be/JO9YxZYd0qY

Steven: We’re in the Louvre, in Paris, looking at one of their most famous objects. This is the Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi.

Beth: Its interesting to me that this is one of the most popular objects to look at here (it was made in the Babylonian Kingdom which is now in Iraq) and I think its because of our modern interest and reliance on law as the founding principles of a civilization. And this is such an ancient object, this is nearly 4,000 years old.

Steven: A stele is a tall carved object. This one is carved in relief at the top, and then below that, and on all sides, we have inscribed cuneiform (script that is used on the stele). It’s written in the language of Akkadian (which is the court language of the Babylonians).

Beth: Which was used for official government decrees.

Steven: But that’s the language. The script is cuneiform. It’s divided into three parts. There’s a prologue, which talks about the scene that’s being represented at the top, the Investiture of Hammurabi. What we see is the king on the left, he’s smaller, and he’s facing the god, Shamash. This is the sun god, the god of justice.

Beth: And we can tell he’s a god because of the special horned crown that he wears and the flames or light that emanate from his shoulders.

Steven: We can think of this as a kind of divine light, the way that in so much Christian imagery, we see a halo.

Beth: And we have that composite view that we often see in Ancient Egyptian and Ancient Near-Eastern art, where the shoulders are frontal but the face is represented in profile.

Steven: Shamash sits on a throne, and if you look closely you can see under his feet the representation of mountains that he rises from each day. He’s giving to the king a scepter and a ring, these are signs of power. Hammurabi is demonstrating here that these are divine laws. That his authority comes from Shamash.

Beth: So we have more than 300 laws here.

Steven: And they’re very particular. Scholars believe that they weren’t so much written by the king as listed from judgments that have already been meted out.

Beth: They’re legal precedents, and they take the form of announcing an action and its consequences. So if you do X, Y is the consequence.

Steven: So, for example, if a man builds a house and the house falls on the owner, the builder is put to death. So there’s a kind of equivalence, and this might remind us of the Biblical law of, “An eye for an eye” or a tooth for a tooth.” Which is also found on the stele, and it’s important and interesting to note that the stele predates that Biblical text. The last part of the text, what is often referred to as the epilogue, speaks to the posterity of the king, of the importance of his rule and the idea that he will be remembered for all time.

Beth: This is certainly not a unique stele in terms of recording laws, but it does survive largely intact. When it was discovered, it was broken only into three parts, which you can still see today.

Steven: These laws, almost 4,000 years old, tell us a tremendous amount about Babylonian culture, about what was important to them. So many of these laws deal with agricultural issues, issues of irrigation, and are clearly expressing points of tension in society.

Beth: A lot of them have to do with family life, too, and the king is, after all, responsible for the peace and prosperity and feeding of his people. And the stele is such a wonderful reminder that Mesopotamia was such an advanced culture. Here, almost 4,000 years ago, we have cities that are dependent on good crop yields, that require laws to maintain civil society. And a reminder of the debt that the world owes to the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and the area that is seeing so much conflict now.

The Ishtar Gate and Neo-Babylonian art and architecture

“I, Nebuchadnezzar … magnificently adorned them with luxurious splendor for all mankind to behold in awe.”

The chronology of Mesopotamia is complicated. Scholars refer to places (Sumer, for example) and peoples (the Babylonians), but also empires (Babylonia) and unfortunately for students of the Ancient Near East these organizing principles do not always agree. The result is that we might, for example, speak of the very ancient Babylonians starting in the 1800s B.C.E. and then also the Neo-Babylonians more than a thousand years later. What came in between you ask? Well, quite a lot, but mostly the Kassites and the Assyrians.

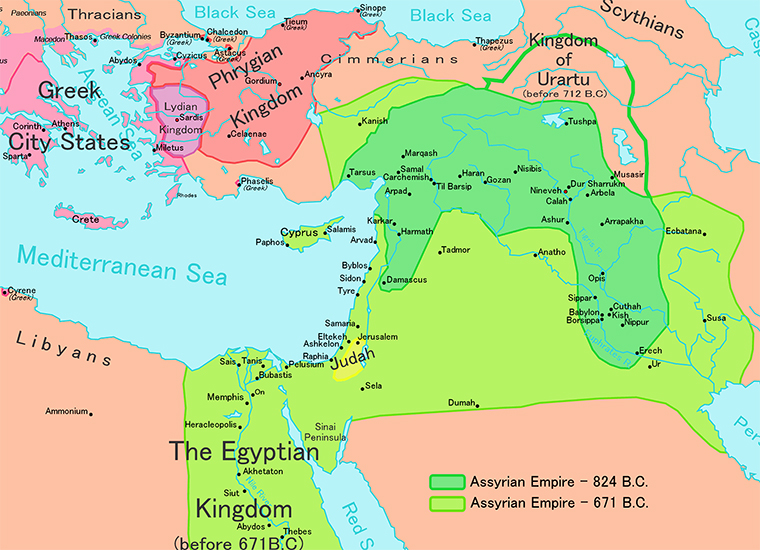

The Assyrian Empire which had dominated the Near East came to an end at around 600 B.C.E. due to a number of factors including military pressure by the Medes (a pastoral mountain people, again from the Zagros mountain range), the Babylonians, and possibly also civil war.

A Neo-Babylonian dynasty

The Babylonians rose to power in the late 7th century and were heirs to the urban traditions which had long existed in southern Mesopotamia. They eventually ruled an empire as dominant in the Near East as that held by the Assyrians before them.

This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia) because Babylon had also risen to power earlier and became an independent city-state, most famously during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.).

In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

Architecture

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar (604-561 B.C.E.) largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar purportedly built the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran). Though mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman writers, the “Hanging Gardens” may, in fact, be legendary.

The Ishtar Gate (today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. The whole gate was covered in lapis lazuli glazed bricks which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

Watch the conversation between Dr. Beth Harris & Dr. Steven Zucker: https://youtu.be/U2iZ83oIZH0

Assyria, an introduction

Led by aggressive warrior kings, Assyria dominated the fertile crescent for half a millennia, amassing vast wealth.

A military culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium B.C.E., led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

Luxurious palaces

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Feats of bravery

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

The destruction of Susa

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa. In the relief at left, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Military victories & exploits

In the Central Palace at Nimrud, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III illustrates his military victories and exploits, including the siege of a city in great detail.

In this scene we see one soldier holding a large screen to protect two archers who are taking aim. The topography includes three different trees and a roaring river, most likely setting the scene in and around the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II: A Conversation

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in the Musee du Louvre, Paris. Watch the video here: https://youtu.be/2GrvBLKaRSI

Steven: Ancient Mesopotamia is often credited as the cradle of civilization, that is, the place where farming and cities began. It makes it seem so peaceful, but this was anything but the case. In fact, it was really a series of civilizations that conquered each other.

Beth: We’re in a room in the Louvre filled with sculpture from the Assyrians, who controlled the ancient Near East from about 1000 B.C.E. to around 500 B.C.E.

Steven: And these sculptures, in particular, come from the palace of Sargon II, and were carved at the height of Assyrian civilization in the eighth century B.C.E.

Beth: So this is modern-day Khorsabad.

Steven: In Iraq.

Beth: And various Assyrian kings established palaces at different cities. So there were palaces at Nimrid and Assur before this, and after, there will be a palace at Nineveh, but these sculptures come from an excavation from modern-day Khorsabad.

Steven: The most impressive sculptures that survive are the guardian figures that protected the city’s gates, and protected the gates of the citadel itself. That is the area within which were both the temple and the royal palace.

Beth: So at each of these various gates, there were guardian figures that were winged bulls with the heads of men.

Steven: We think they were called lamassu.

Beth: As figures that stood at gateways, they make sense. They’re fearsome, they look powerful. They could also be an expression of the power of the Assyrian king.

Steven: They are enormous, but even they would have been dwarfed by the architecture. They would have stood between huge arches. In fact, they had some structural purpose. It’s interesting to note that each of these lamassu is actually carved out of monolithic stone, that is, there are no cuts here. These are single pieces of stone, and in the ancient world, it was no small task to get these stones in place.

Beth: Well, and apparently, there were relief carvings in the palace that depicted moving these massive lamassu into place. So it’s important to remember that the lamassu were the gateway figures, but the walls of the palace were decorated with relief sculpture showing hunting scenes and other scenes indicating royal power.

Steven: This is a lamassu that was actually a guardian for the exterior gate of the city. It’s in awfully good condition.

Beth: Well my favorite part is the crown. It’s decorated with rosettes, and then double horns that come around toward the top center, and then on top of that, a ring of feathers.

Steven: It’s really delicate for such a massive and powerful creature. The faces are extraordinary. First of all, just at the top of the forehead, you can see kind of incised wavy hair that comes just below the crown, and then you have a connected eyebrow.

Beth: And then the ears are the ears of a bull that wear earrings.

Steven: Actually quite elaborate earrings.

Beth: The whole form is so decorative.

Steven: And then there’s that marvelous, complex representation of the beard. You see little ringlets on the cheeks of the face, but then as the beard comes down, you see these spirals that turn downward and then are interrupted by a series of horizontal bands.

Beth: Then the wings, too, form this lovely decorative pattern up the side of the animal, and then across its back.

Steven: In fact, across the body itself there are ringlets as well, so we get a sense of the fur of the beast. And then under the creature, and around the legs, you can see inscriptions in cuneiform.

Beth: Some of which declares the power of the king…

Steven: …and damnation for those that would threaten the king’s work, that is, the citadel.

Beth: What’s interesting too is that these were meant to be seen both from a frontal view and a profile view.

Steven: Well if you count up the number of legs, there’s one too many. There are five.

Beth: Right, two from the front, and four from the side, but of course, one of the front legs overlaps, and so there are five legs.

Steven: What’s interesting is that when you look at the creature from the side, you actually see that it’s moving forward, but when you look at it from the front, those two legs are static so the beast is stationary. And think about what this means for a guardian figure at a gate. As we approach, we see it still, watching us as we move, but if we belong, if we’re friendly, and were allowed to pass this gate, as we move through it, we see the animal itself move.

Beth: And then we have this combination of these decorative forms that we’ve been talking about with a sensitivity to the anatomy of this composite animal. His abdomen swells, and his hindquarters move back, and then we can see the veins, and muscles, and bones in his leg.

Steven: So there really is this funny relationship between the naturalistic and the imagination of this culture.

Beth: And the decorative, but all speaking to the power, the authority of the king and the fortifications of this palace, and this city.

Steven: They are incredibly impressive. It would be impossible to broach the citadel without being awestruck by the power of this civilization.

Ancient Persia, an introduction

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century B.C.E., the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

A tolerant empire

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, the Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century B.C.E.

The Apadana

Persepolis included a massive columned hall used for receptions by the Kings, called the Apadana. This hall contained 72 columns and two monumental stairways.

The walls of the spaces and stairs leading up to the reception hall were carved with hundreds of figures, several of which illustrated subject peoples of various ethnicities, bringing tribute to the Persian king.

Conquered by Alexander the Great

The Persian Empire was, famously, conquered by Alexander the Great. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying the last Persian emperor, Darius III, in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

By the early fifth century B.C.E. the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth. Through regional administrators the Persian kings controlled a vast territory which they constantly sought to expand. Famous for monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous monumental centers, among those is Persepolis (today, in Iran). The great audience hall of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes presents a visual microcosm of the Achaemenid empire—making clear, through sculptural decoration, that the Persian king ruled over all of the subjugated ambassadors and vassals (who are shown bringing tribute in an endless eternal procession).

Overview of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) was an imperial state of Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great and flourishing from c. 550-330 B.C.E. The empire’s territory was vast, stretching from the Balkan peninsula in the west to the Indus River valley in the east. The Achaemenid Empire is notable for its strong, centralized bureaucracy that had, at its head, a king and relied upon regional satraps (regional governors).

A number of formerly independent states were made subject to the Persian Empire. These states covered a vast territory from central Asia and Afghanistan in the east to Asia Minor, Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west. The Persians famously attempted to expand their empire further to include mainland Greece but they were ultimately defeated in this attempt. The Persian kings are noted for their penchant for monumental art and architecture. In creating monumental centers, including Persepolis, the Persian kings employed art and architecture to craft messages that helped to reinforce their claims to power and depict, iconographically, Persian rule.

Overview of Persepolis

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Persian empire (c. 550-330 B.C.E.), lies some 60 km northeast of Shiraz, Iran. The earliest archaeological remains of the city date to c. 515 B.C.E. Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians”, was known to the Persians as Pārsa and was an important city of the ancient world, renowned for its monumental art and architecture. The site was excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter, and Erich Schmidt between 1931 and 1939. Its remains are striking even today, leading UNESCO to register the site as a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Persepolis was intentionally founded in the Marvdašt Plain during the later part of the sixth century B.C.E. It was marked as a special site by Darius the Great (reigned 522-486 B.C.E.) in 518 B.C.E. when he indicated the location of a “Royal Hill” that would serve as a ceremonial center and citadel for the city. This was an action on Darius’ part that was similar to the earlier king Cyrus the Great who had founded the city of Pasargadae. Darius the Great directed a massive building program at Persepolis that would continue under his successors Xerxes (r. 486-466 B.C.E.) and Artaxerxes I (r. 466-424 B.C.E.). Persepolis would remain an important site until it was sacked, looted, and burned under Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 B.C.E.

Darius’ program at Persepolis including the building of a massive terraced platform covering 125,000 square meters of the promontory. This platform supported four groups of structures: residential quarters, a treasury, ceremonial palaces, and fortifications. Scholars continue to debate the purpose and nature of the site. Primary sources indicate that Darius saw himself building an important stronghold. Some scholars suggest that the site has a sacred connection to the god Mithra (Mehr), as well as links to the Nowruz, the Persian New Year’s festival. More general readings see Persepolis as an important administrative and economic center of the Persian empire.

Apādana

The Apādana palace is a large ceremonial building, likely an audience hall with an associated portico. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan, meaning that the roof of the structure is supported by columns. Apādana is the Persian term equivalent to the Greek hypostyle (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστυλος hypóstȳlos). The footprint of the Apādana is c. 1,000 square meters; originally 72 columns, each standing to a height of 24 meters, supported the roof (only 14 columns remain standing today). The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls (as seen above), eagles or lions, all animals represented royal authority and kingship.

The king of the Achaemenid Persian empire is presumed to have received guests and tribute in this soaring, imposing space. To that end a sculptural program decorates monumental stairways on the north and east. The theme of that program is one that pays tribute to the Persian king himself as it depicts representatives of 23 subject nations bearing gifts to the king.

The Apādana stairs and sculptural program

The monumental stairways that approach the Apādana from the north and the east were adorned with registers of relief sculpture that depicted representatives of the twenty-three subject nations of the Persian empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king. The sculptures form a processional scene, leading some scholars to conclude that the reliefs capture the scene of actual, annual tribute processions—perhaps on the occasion of the Persian New Year–that took place at Persepolis. The relief program of the northern stairway was perhaps completed c. 500-490 B.C.E. The two sets of stairway reliefs mirror and complement each other. Each program has a central scene of the enthroned king flanked by his attendants and guards.

Noblemen wearing elite outfits and military apparel are also present. The representatives of the twenty-three nations, each led by an attendant, bring tribute while dressed in costumes suggestive of their land of origin. Margaret Root interprets the central scenes of the enthroned king as the focal point of the overall composition, perhaps even reflecting events that took place within the Apādana itself.

The relief program of the Apādana serves to reinforce and underscore the power of the Persian king and the breadth of his dominion. The motif of subjugated peoples contributing their wealth to the empire’s central authority serves to visually cement this political dominance. These processional scenes may have exerted influence beyond the Persian sphere, as some scholars have discussed the possibility that Persian relief sculpture from Persepolis may have influenced Athenian sculptors of the fifth century B.C.E. who were tasked with creating the Ionic frieze of the Parthenon in Athens. In any case, the Apādana, both as a building and as an ideological tableau, make clear and strong statements about the authority of the Persian king and present a visually unified idea of the immense Achaemenid empire.

writing system developed in ancient Sumer from the Latin for wedge (cuneus) + form (shaped)

unpaid labor coerced by the state/slavery

beliefs about the order and structure of the universe

in sculpture, the quality of having a clear front designed to face the viewer

a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse (intaglio) and hung on strings of fiber or leather

from the Latin, tagliare (to cut). May refer to carving stone or other hard material to produce a positive image when impressed upon soft material, like clay. May also refer to a printing process in which lines are cut or etched into a metal plate and then, when inked, transfer that inked mark to paper.

[From Greek eikon meaning "image" + glúphō meaning "to carve" or "to write"] The visual images and symbols used in a work of art or the study or interpretation of these [Art History Glossary]

a sculpture technique in which a clay mold is coated in wax, covered in plaster, and then heated, causing the wax to run out. Molten metal is then poured into the resulting channels, allowed to cool, and the mold broken so that the sculpture can be removed and polished.

a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or relief carving

a very hard igneous rock, similar to granite though generally darker in color

from the Greek pan- (all) plus theos (gods). The collected deities of a particular group or region.

a drink, generally one poured out as an offering to a deity

human-headed winged lion figures, often carved in stone as guardian figures of Assyrian palace entrances

characterized by a forest of columns supporting the roof