6

Dr. Amy Calvert; British Museum; Dr. Naraelle Hohensee; Dr. Beth Harris; Dr. Steven Zucker; Lumen Learning; and Dr. Elizabeth Cummins

In this chapter

Ancient Egypt (Introduction)

Pre-Dynastic & Early Dynastic Periods

Old Kingdom

- Great Pyramids of Giza

- Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Sphinx

- King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and Queen

- Seated Scribe

Middle Kingdom

New Kingdom

- Temple of Amun-Re and the hypostyle hall at Karnak

- Valley of the Kings

- Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

- Paintings from the tomb chapel of Nebamun

Amarna

- House altar depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and three of their daughters

- Portrait head of Queen Tiye

- Model bust of Nefertiti: a conversation

New Kingdom, resumed

Ancient Egypt, an introduction

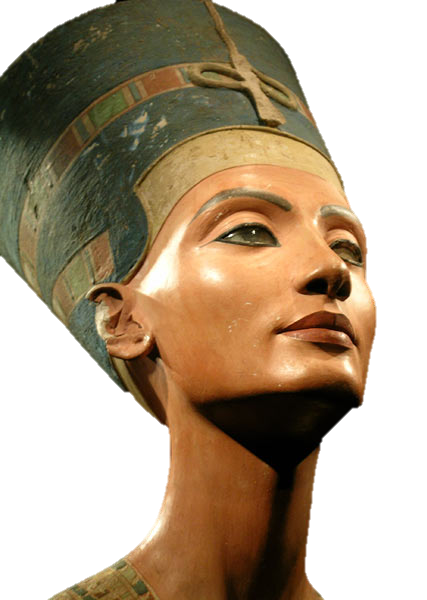

Egypt’s impact on later cultures was immense. You could say that Egypt provided the building blocks for Greek and Roman culture, and, through them, influenced all of the Western tradition. Today, Egyptian imagery, concepts, and perspectives are found everywhere; you will find them in architectural forms, on money, and in our day to day lives. Many cosmetic surgeons, for example, use the silhouette of Queen Nefertiti (whose name means “the beautiful one has come”) in their advertisements.

Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for more than 3000 years and showed an incredible amount of continuity. That is more than 15 times the age of the United States, and consider how often our culture shifts; less than 10 years ago, there was no Facebook, Twitter, or Youtube.

While today we consider the Greco-Roman period to be in the distant past, it should be noted that Cleopatra VII’s reign (which ended in 30 B.C.E.) is closer to our own time than it was to that of the construction of the pyramids of Giza. It took humans nearly 4000 years to build something–anything–taller than the Great Pyramids. Contrast that span to the modern era; we get excited when a record lasts longer than a decade.

Consistency and stability

Egypt’s stability is in stark contrast to the Ancient Near East of the same period, which endured an overlapping series of cultures and upheavals with amazing regularity. The earliest royal monuments, such as the Narmer Palette carved around 3100 B.C.E., display identical royal costumes and poses as those seen on later rulers, even Ptolemaic kings on their temples 3000 years later.

A vast amount of Egyptian imagery, especially royal imagery that was governed by decorum (a sense of what was ‘appropriate’), remained stupefyingly consistent throughout its history. This is why, especially to the untrained eye, their art appears extremely static—and in terms of symbols, gestures, and the way the body is rendered, it was. It was intentional. The Egyptians were aware of their consistency, which they viewed as stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of the correctness of their culture.

This consistency was closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself—tomb scenes of the deceased receiving food, or temple scenes of the king performing perfect rituals for the gods—were functionally causing those things to occur in the divine realm. If the image of the bread loaf was omitted from the deceased’s table, they had no bread in the Afterlife; if the king was depicted with the incorrect ritual implement, the ritual was incorrect and this could have dire consequences. This belief led to an active resistance to change in codified depictions.

The earliest recorded tourist graffiti on the planet came from a visitor from the time of Ramses II who left their appreciative mark at the already 1300-year-old site of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the earliest of the massive royal stone monuments. They were understandably impressed by the works of their ancestors and endeavored to continue that ancient legacy.

Geography

Egypt is a land of duality and cycles, both in topography and culture. The geography is almost entirely rugged, barren desert, except for an explosion of green that straddles either side of the Nile as it flows the length of the country. The river emerges from far to the south, deep in Africa, and empties into the Mediterranean sea in the north after spreading from a single channel into a fan-shaped system, known as a delta, at its northernmost section.

The influence of this river on Egyptian culture and development cannot be overstated—without its presence, the civilization would have been entirely different. The Nile provided not only a constant source of life-giving water, but created the fertile lands that fed the growth of this unique (and uniquely resilient) culture.

Each year, fed by melting snows in the far-off headlands, the river overflowed its banks in an annual flood that covered the ground with a rich, black silt and produced incredibly fertile fields. The Egyptians referred to this as Kemet, the “black lands,” and contrasted this dense, dark soil against the Deshret, the “red lands” of the sterile desert; the line between these zones was (and in most cases still is) a literal line. The visual effect is stark, appearing almost artificial in its precision.

Time – cyclical and linear

The annual inundation of the Nile was also a reliable, and measurable, cycle that helped form their concept of the passage of time. In fact, the calendar we use today is derived from one developed by the ancient Egyptians. They divided the year into 3 seasons: akhet “inundation,” peret “growing/emergence.” and shemw “harvest.” Each season was, in turn, divided into four 30-day months. Although this annual cycle, paired with the daily solar cycle that is so evident in the desert, led to a powerful drive to see the universe in cyclical time, this idea existed simultaneously with the reality of linear time.

These two concepts—the cyclical and the linear—came to be associated with two of their primary deities: Osiris, the eternal lord of the dead, and Re, the sun god who was reborn with each dawn.

Early development: The Predynastic period

The civilization of Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation. “Dynastic” Egypt—sometimes referred to as “Pharaonic” (after “pharaoh,” the Greek title of the Egyptian kings derived from the Egyptian title per aA, “Great House”) which was the time when the country was largely unified under a single ruler, begins around 3100 B.C.E.

The period before this, lasting from about 5000 B.C.E. until unification, is referred to as Predynastic by modern scholars. Prior to this were thriving Paleolithic and Neolithic groups, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years, descended from northward migrating homo erectus who settled along the Nile Valley. During the Predynastic period, ceramics, figurines, mace heads, and other artifacts such as slate palettes used for grinding pigments, begin to appear, as does imagery that will become iconic during the Pharaonic era—we can see the first hints of what is to come.

Dynasties

It is important to recognize that the dynastic divisions modern scholars use were not used by the ancients themselves. These divisions were created in the first Western-style history of Egypt, written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the 3rd century B.C.E. Each of the 33 dynasties included a series of rulers usually related by kinship or the location of their seat of power. Egyptian history is also divided into larger chunks, known as “kingdoms” and “periods,” to distinguish times of strength and unity from those of change, foreign rule, or disunity.

| Period | Dates |

|---|---|

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) | c. 2649-2150 BCE |

| First Intermediate Period | c. 2150-2030 BCE |

| Middle Kingdom | c. 2030-1640 BCE |

| Second Intermediate Period (Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) | c. 1640-1540 BCE |

| New Kingdom | c. 1550-1070 BCE |

| Third Intermediate Period | c. 1070-713 BCE |

| Late Period (a series from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan and Persian rulers) | c. 712-332 BCE |

| Ptolemaic Period (ruled by Greco-Romans) | c. 332-30 BCE |

The Egyptians themselves referred to their history in relation to the ruler of the time. Years were generally recorded as the regnal dates (from the Latin regnum, meaning kingdom or rule) of the ruling king, so that with each new reign, the numbers began anew. Later kings recorded the names of their predecessors in vast “king-lists” on the walls of their temples and depicted themselves offering to the rulers who came before them—one of the best known examples is in the temple of Seti I at Abydos.

These lists were often condensed, with some rulers (such as the contentious and disruptive Akhenaten) and even entire dynasties omitted from the record; they are not truly history, rather they are a form of ancestor worship, a celebration of the consistency of kingship of which the current ruler was a part.

The pharaoh—not just a king

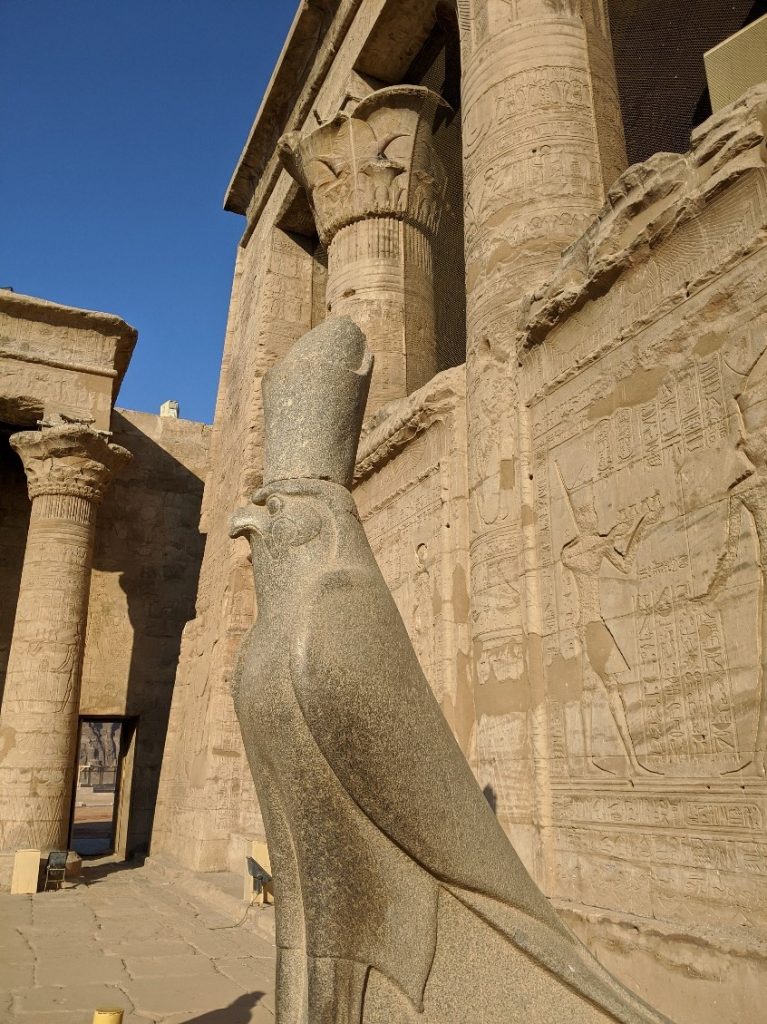

Kings in Egypt were complex intermediaries that straddled the terrestrial and divine realms. They were, obviously, living humans, but upon accession to the throne, they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler. This divine aspect of the office of kingship was what gave authority to the human ruler. The living king was associated with the god Horus, the powerful, virile falcon-headed god who was believed to bestow the throne to the first human king.

Horus’s immensely important father, Osiris, was the lord of the underworld. One of the original divine rulers of Egypt, this deity embodied the promise of regeneration. Cruelly murdered by his brother Seth, the god of the chaotic desert, Osiris was revived through the potent magic of his wife Isis. Through her knowledge and skill, Osiris was able to sire the miraculous Horus, who avenged his father and threw his criminal uncle off the throne to take his rightful place.

Osiris became ruler of the realm of the dead, the eternal source of regeneration in the Afterlife. Deceased kings were identified with this god, creating a cycle where the dead king fused with the divine king of the dead and his successor “defeated” death to take his place on the throne as Horus.

Ancient Egyptian art

Appreciating and understanding ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art must be viewed from the standpoint of the ancient Egyptians to understand it. The somewhat static, usually formal, strangely abstract, and often blocky nature of much Egyptian imagery has, at times, led to unfavorable comparisons with later, and much more ‘naturalistic,’ Greek or Renaissance art. However, the art of the Egyptians served a vastly different purpose than that of these later cultures.

Art not meant to be seen

While today we marvel at the glittering treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun, the sublime reliefs in New Kingdom tombs, and the serene beauty of Old Kingdom statuary, it is imperative to remember that the majority of these works were never intended to be seen—that was simply not their purpose.

The function of Egyptian art

These images, whether statues or relief, were designed to benefit a divine or deceased recipient. Statuary provided a place for the recipient to manifest and receive the benefit of ritual action. Most statues show a formal frontality, meaning they are arranged straight ahead, because they were designed to face the ritual being performed before them. Many statues were also originally placed in recessed niches or other architectural settings—contexts that would make frontality their expected and natural mode.

Statuary, whether divine, royal, or elite, provided a kind of conduit for the spirit (or ka) of that being to interact with the terrestrial realm. Divine cult statues (few of which survive) were the subject of daily rituals of clothing, anointing, and perfuming with incense and were carried in processions for special festivals so that the people could “see” them (they were almost all entirely shrouded from view, but their ‘presence’ was felt).

Royal and elite statuary served as intermediaries between the people and the gods. Family chapels with the statuary of a deceased forefather could serve as a sort of ‘family temple.’ There were festivals in honor of the dead, where the family would come and eat in the chapel, offering food for the Afterlife, flowers (symbols of rebirth), and incense (the scent of which was considered divine). Preserved letters let us know that the deceased was actively petitioned for their assistance, both in this world and the next.

What we see in museums

Generally, the works we see on display in museums were products of royal or elite workshops; these pieces fit best with our modern aesthetic and ideas of beauty. Most museum basements, however, are packed with hundreds (even thousands!) of other objects made for people of lower status—small statuary, amulets, coffins, and stelae (similar to modern tombstones) that are completely recognizable, but rarely displayed. These pieces generally show less quality in the workmanship; being oddly proportioned or poorly executed; they are less often considered ‘art’ in the modern sense. However, these objects served the exact same function of providing benefit to their owners (and to the same degree of effectiveness), as those made for the elite.

Modes of representation for three-dimensional art

Three-dimensional representations, while being quite formal, also aimed to reproduce the real-world—statuary of gods, royalty, and the elite was designed to convey an idealized version of that individual. Some aspects of ‘naturalism’ were dictated by the material. Stone statuary, for example, was quite closed—with arms held close to the sides, limited positions, a strong back pillar that provided support, and with the fill spaces left between limbs.

Wood and metal statuary, in contrast, was more expressive—arms could be extended and hold separate objects, spaces between the limbs were opened to create a more realistic appearance, and more positions were possible. Stone, wood, and metal statuary of elite figures, however, all served the same functions and retained the same type of formalization and frontality. Only statuettes of lower status people displayed a wide range of possible actions, and these pieces were focused on the actions, which benefited the elite owner, not the people involved.

Modes of representation for two-dimensional art

Two-dimensional art represented the world quite differently. Egyptian artists embraced the two-dimensional surface and attempted to provide the most representative aspects of each element in the scenes rather than attempting to create vistas that replicated the real world.

Each object or element in a scene was rendered from its most recognizable angle and these were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but eye and shoulders frontally. These scenes are complex composite images that provide complete information about the various elements, rather than ones designed from a single viewpoint, which would not be as comprehensive in the data they conveyed.

Registers

Scenes were ordered in parallel lines, known as registers. These registers separate the scene as well as provide ground lines for the figures. Scenes without registers are unusual and were generally only used to specifically evoke chaos; battle and hunting scenes will often show the prey or foreign armies without groundlines. Registers were also used to convey information about the scenes—the higher up in the scene, the higher the status; overlapping figures imply that the ones underneath are further away, as are those elements that are higher within the register.

Hierarchy of scale

Difference in scale was the most commonly used method for conveying hierarchy—the larger the scale of the figures, the more important they were. Kings were often shown at the same scale as deities, but both are shown larger than the elite and far larger than the average Egyptian.

Text and image

Text accompanied almost all images. In statuary, identifying text will appear on the back pillar or base, and relief usually has captions or longer texts that complete and elaborate on the scenes. Hieroglyphs were often rendered as tiny works of art in themselves, even though these small pictures do not always stand for what they depict; many are instead phonetic sounds. Some, however, are logographic, meaning they stand for an object or concept.

The lines blur between text and image in many cases. For instance, the name of a figure in the text on a statue will regularly omit the determinative (an unspoken sign at the end of a word that aids identification–for example, verbs of motion are followed by a pair of walking legs, names of men end with the image of a man, names of gods with the image of a seated god, etc.) at the end of the name. In these instances, the representation itself serves this function.

The Rosetta Stone

The key to translating hieroglyphics

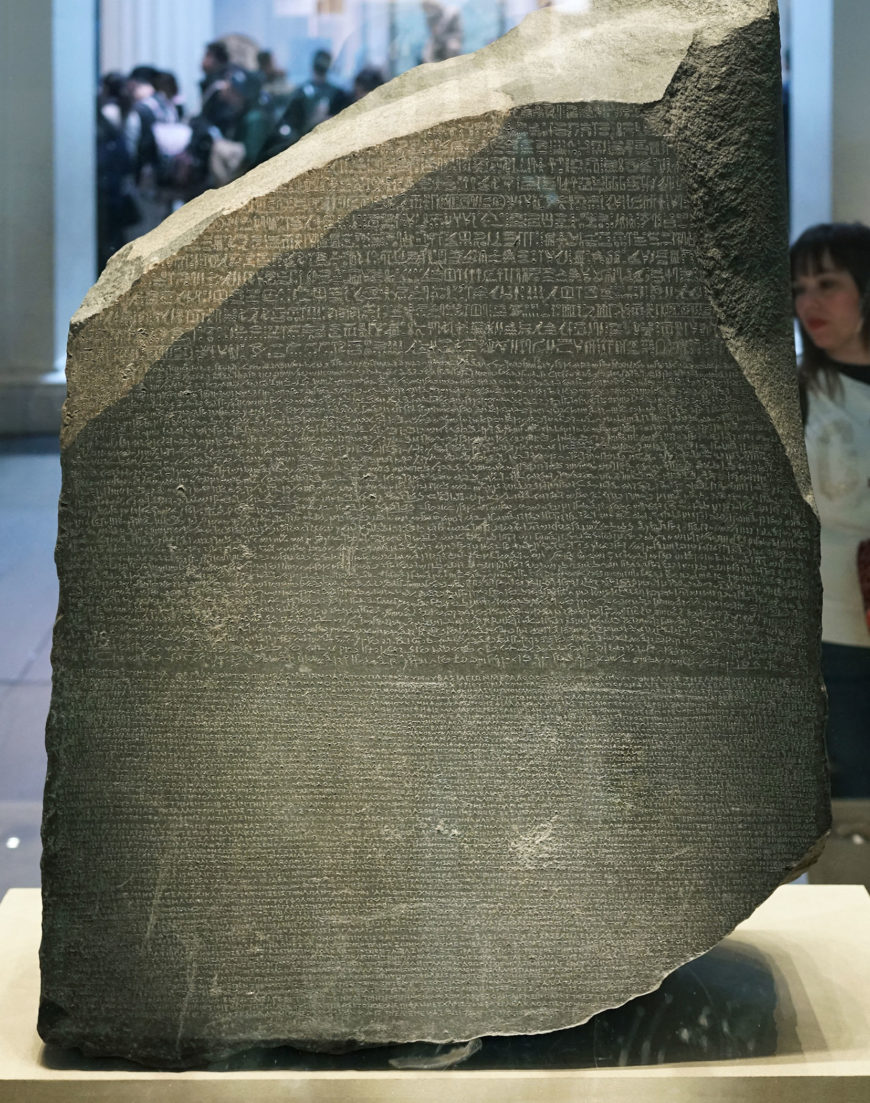

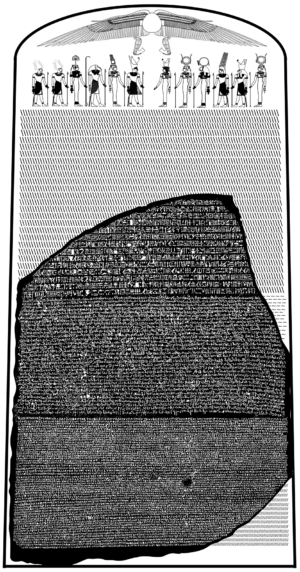

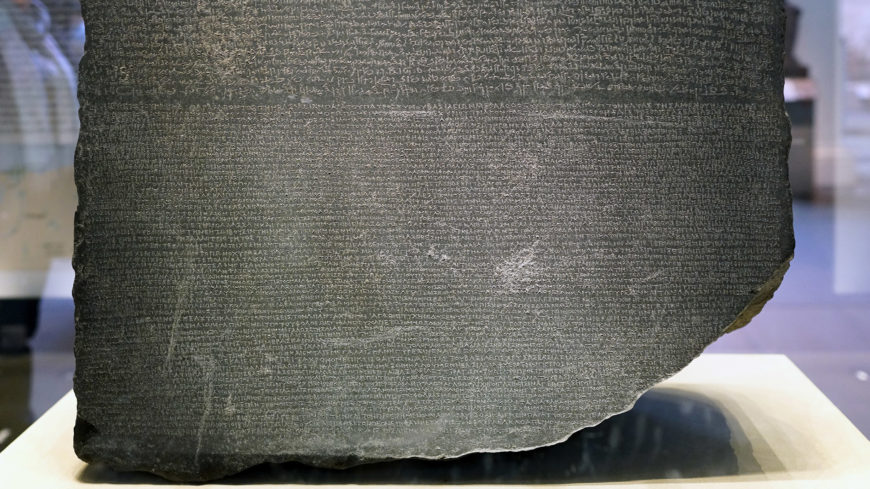

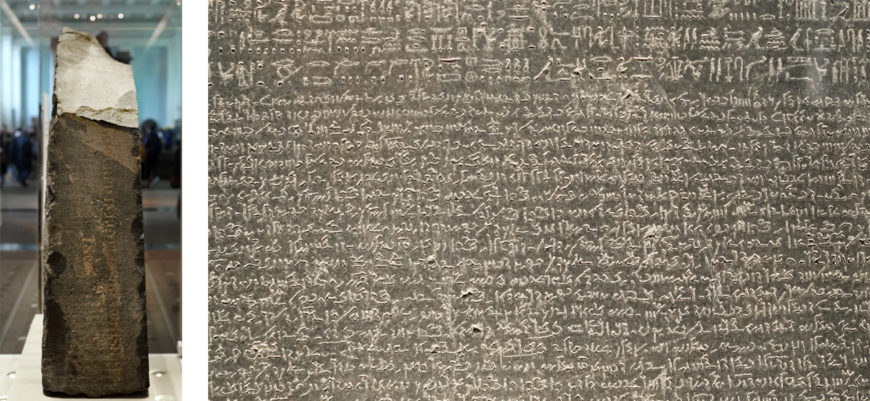

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most important objects in the British Museum as it holds the key to understanding Egyptian hieroglyphs—a script made up of small pictures that was used originally in ancient Egypt for religious texts. Hieroglyphic writing died out in Egypt in the fourth century C.E.. Over time the knowledge of how to read hieroglyphs was lost, until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 and its subsequent decipherment.

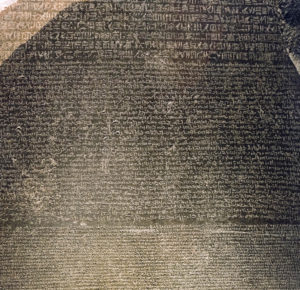

The Stone is a tablet of black rock called granodiorite. It is part of a larger inscribed stone that would have stood some 2 meters high. The top part of the stone has broken off at an angle—in line with a band of pink granite whose crystalline structure glints a little in the light. The back of the Rosetta stone is rough, where it has been hewn into shape, but the front face is smooth and crammed with text, inscribed in three different scripts. These form three distinct bands of writing.

Three translations of the same decree

The inscriptions are three translations of the same decree, passed by a council of priests, that affirms the royal cult of the thirteen-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation. The decree is inscribed on the stone three times, in hieroglyphic (suitable for a priestly decree), demotic (the native script used for daily purposes), and Greek (the language of the administration). The importance of this to Egyptology is immense. In the early years of the nineteenth century, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to deciphering the others.

Opposition to the Ptolemies

In previous years the family of the Ptolemies had lost control of certain parts of the country. It had taken their armies some time to put down opposition in the Delta, and parts of southern Upper Egypt, particularly Thebes, were not yet back under the government’s control.

Before the Ptolemaic era (that is before about 332 B.C.E.), decrees in hieroglyphs such as this were usually set up by the king. It shows how much things had changed from Pharaonic times that the priests, the only people who had kept the knowledge of writing hieroglyphs, were now issuing such decrees. The list of good deeds done by the king for the temples hints at the way in which the support of the priests was ensured.

The end of hieroglyphics

Soon after the end of the fourth century C.E., when hieroglyphs had gone out of use, the knowledge of how to read and write them disappeared. In the early years of the nineteenth century, some 1400 years later, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to decipher them.

The discovery

Thomas Young, an English physicist, was the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, that of Ptolemy. The French scholar Jean-François Champollion then realized that hieroglyphs recorded the sound of the Egyptian language and laid the foundations of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language and culture.

Soldiers in Napoleon’s army discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799 while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of el-Rashid (Rosetta). On Napoleon’s defeat, the stone became the property of the British under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria (1801) along with other antiquities that the French had found.

The Rosetta Stone has been exhibited in the British Museum since 1802, with only one break. Towards the end of the First World War, in 1917, when the Museum was concerned about heavy bombing in London, they moved it to safety along with other, portable, ‘important’ objects. The Rosetta Stone spent the next two years in a station on the Postal Tube Railway 50 feet below the ground at Holborn.

Analyzing the Rosetta Stone

When the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799, the carved characters that covered its surface were quickly copied. Printer’s ink was applied to the Stone and white paper was laid over it. When the paper was removed, it revealed an exact copy of the text—but in reverse. Since then, many copies or “facsimiles” have been made using a variety of materials. Inevitably, the surface of the Stone accumulated many layers of material left over from these activities, despite attempts to remove any residue. Once on display, the grease from many thousands of human hands eager to touch the Stone added to the problem.

An opportunity for investigation and cleaning the Rosetta Stone arose when this famous object was made the centerpiece of the Cracking Codes exhibition at The British Museum in 1999. When work commenced to remove all but the original, ancient material, the stone was black with white lettering. As treatment progressed, the different substances uncovered were analyzed. Grease from human handling, a coating of carnauba wax from the early 1800s and printer’s ink from 1799 were cleaned away using cotton wool swabs and liniment of soap, white spirit, acetone and purified water. Finally, white paint in the text, applied in 1981, which had been left in place until now as a protective coating, was removed with cotton swabs and purified water. A small square at the bottom left corner of the face of the Stone was left untouched to show the darkened wax and the white infill.

The Stone has a dark grey-pinkish tone with a pink streak running through it. Today you can see traces of a reddish brown in the text. This material was analyzed and found to be a clear mineral known as hydroxyapatite; the color may be due to iron traces. The mineral may have been applied deliberately, but there is no proof of this. This substance is not known by experts to have been used as a pigment, nor to have been used as a base for painting (a ground) in ancient Egypt.

Translation of the demotic text

[Year 9, Xandikos day 4], which is equivalent to the Egyptian month, second month of Peret, day 18, of the King “The Youth who has appeared as King in the place of his Father,” the Lord of the Uraei “Whose might is great, who has established Egypt, causing it to prosper, whose heart is beneficial before the gods…” Read the rest of the Rosetta Stone translation here

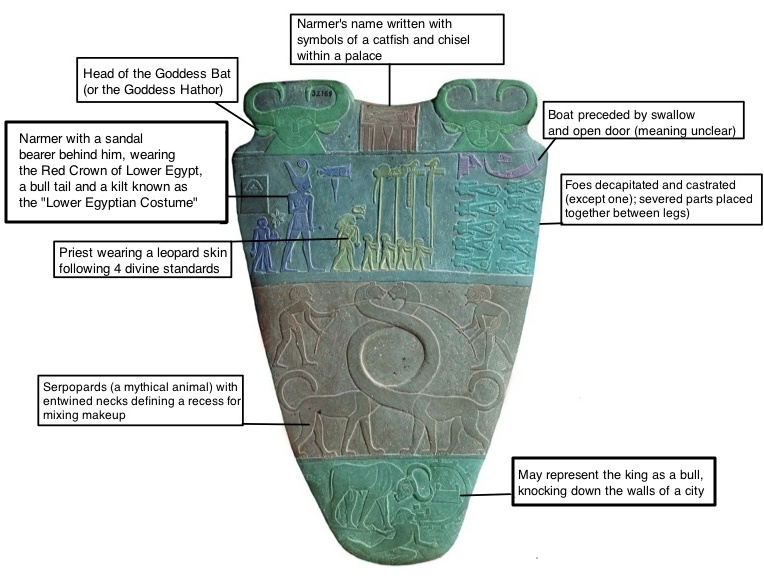

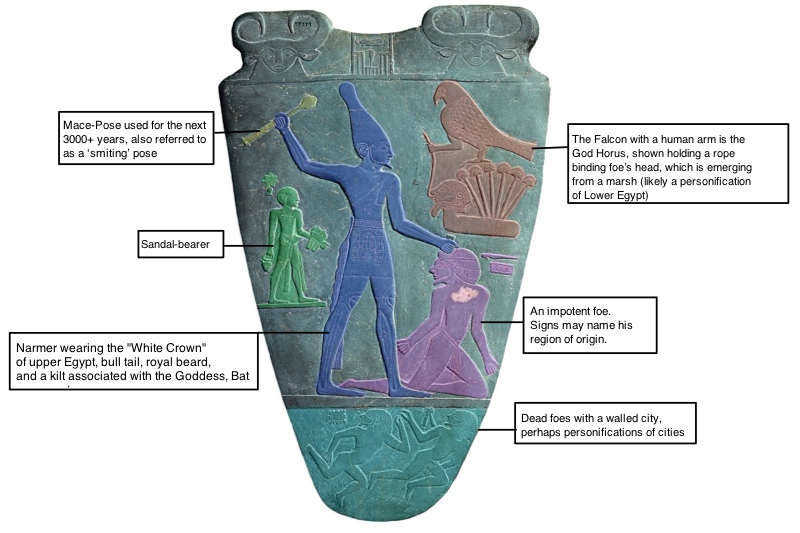

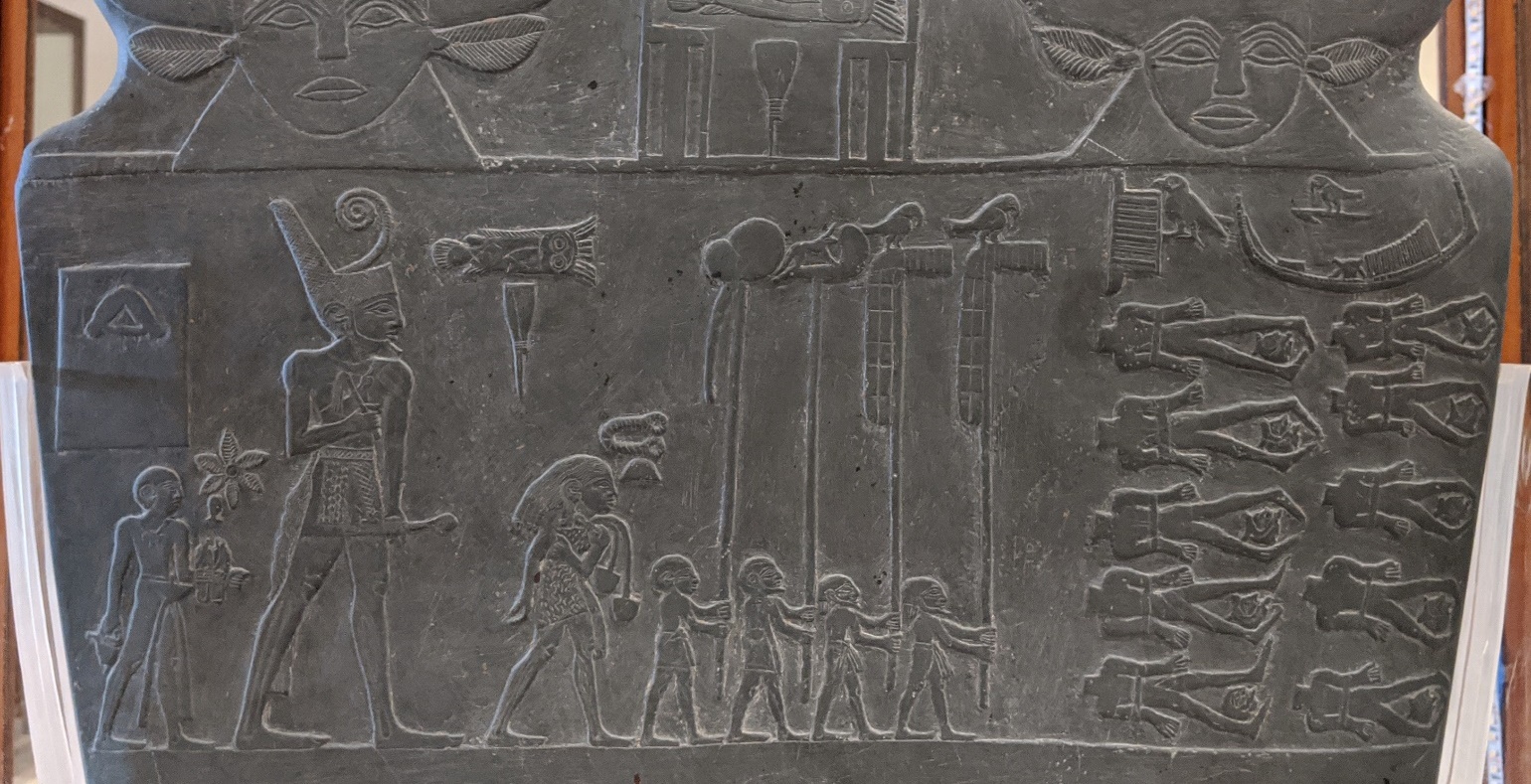

Palette of King Narmer

Vitally important, but difficult to interpret

Some artifacts are of such vital importance to our understanding of ancient cultures that they are truly unique and utterly irreplaceable. The gold mask of Tutankhamun was allowed to leave Egypt for display overseas; the Narmer Palette, on the other hand, is so valuable that it has never been permitted to leave the country.

Discovered among a group of sacred implements ritually buried in a deposit within an early temple of the falcon god Horus at the site of Hierakonpolis (the capital of Egypt during the pre-dynastic period), this large ceremonial object is one of the most important artifacts from the dawn of Egyptian civilization. The beautifully carved palette, 63.5 cm (more than 2 feet) in height and made of smooth grayish-green siltstone, is decorated on both faces with detailed low relief. These scenes show a king, identified by name as Narmer, and a series of ambiguous scenes that have been difficult to interpret and have resulted in a number of theories regarding their meaning.

The high quality of the workmanship, its original function as a ritual object dedicated to a god, and the complexity of the imagery clearly indicate that this was a significant object, but a satisfactory interpretation of the scenes has been elusive.

What was the palette used for?

The object itself is a monumental version of a type of daily use item commonly found in the Predynastic period—palettes were generally flat, minimally decorated stone objects used for grinding and mixing minerals for cosmetics. Dark eyeliner was an essential aspect of life in the sun-drenched region; like the dark streaks placed under the eyes of modern athletes, black cosmetic around the eyes served to reduce glare. Basic cosmetic palettes were among the typical grave goods found during this early era.

In addition to these simple, purely functional, palettes however, there were also a number of larger, far more elaborate palettes created in this period. These objects still served the function of being a ground for grinding and mixing cosmetics, but they were also carefully carved with relief sculpture. Many of the earlier palettes display animals —some real, some fantastic—while later examples, like the Narmer palette, focus on human actions. Research suggests that these decorated palettes were used in temple ceremonies, perhaps to grind or mix makeup to be ritually applied to the image of the god. Later temple ritual included elaborate daily ceremonies involving the anointing and dressing of divine images; these palettes likely indicate an early incarnation of this process.

A ceremonial object, ritually buried

The Palette of Narmer was discovered in 1898 by James Quibell and Frederick Green. It was found with a collection of other objects that had been used for ceremonial purposes and then ritually buried within the temple at Hierakonpolis.

Temple caches of this type are not uncommon. There was a great deal of focus on ritual and votive objects (offerings to the God) in temples. Every ruler, elite individual, and anyone else who could afford it, donated items to the temple to show their piety and increase their connection to the deity. After a period of time, the temple would be full of these objects and space would need to be cleared for new votive donations. However, since they had been dedicated to a temple and sanctified, the old items that needed to be cleared out could not simply be thrown away or sold. Instead, the general practice was to bury them in a pit under the temple floor. Often, these caches include objects from a range of dates and a mix of types, from royal statuary to furniture.

The “Main Deposit” at Hierakonpolis, where the Narmer Palette was discovered, contained many hundreds of objects, including a number of large relief-covered ceremonial mace-heads, ivory statuettes, carved knife handles, figurines of scorpions and other animals, stone vessels, and a second elaborately decorated palette (now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford) known as the Two Dogs Palette.

Conventions that remain the same for thousands of years

There are several reasons the Narmer Palette is considered to be of such importance. First, it is one of very few such palettes discovered in a controlled excavation. Second, there are a number of formal and iconographic characteristics appearing on the Narmer palette that remain conventional in Egyptian two-dimensional art for the following three millennia. These include the way the figures are represented, the scenes being organized in regular horizontal zones known as registers, and the use of hierarchical scale to indicate relative importance of the individuals. In addition, much of the regalia worn by the king, such as the crowns, kilts, royal beard, and bull tail, as well as other visual elements, such as the pose Narmer takes on one of the faces where he grasps an enemy by the hair and prepares to smash his skull with a mace, continue to be utilized from this time all the way through the Roman era.

What we see on the palette

The king is represented twice in human form, once on each face, followed by his sandal-bearer. He may also be represented as a powerful bull, destroying a walled city with his massive horns, in a mode that again becomes conventional—pharaoh is regularly referred to as “Strong Bull.”

The king is represented twice in human form, once on each face, followed by his sandal-bearer. He may also be represented as a powerful bull, destroying a walled city with his massive horns, in a mode that again becomes conventional—pharaoh is regularly referred to as “Strong Bull.”

In addition to the primary scenes, the palette includes a pair of fantastic creatures, known as serpopards—leopards with long, snaky necks—who are collared and controlled by a pair of attendants. Their necks entwine and define the recess where the makeup preparation took place. The lowest register on both sides include images of dead foes, while both uppermost registers display hybrid human-bull heads and the name of the king. The frontal bull heads are likely connected to a sky goddess known as Bat and are related to heaven and the horizon. The name of the king, written hieroglyphically as a catfish and a chisel, is contained within a squared element that represents a palace façade.

Possible interpretation: unification of Upper and Lower Egypt

As mentioned above, there have been a number of theories related to the scenes carved on this palette. Some have interpreted the battle scenes as a historical narrative record of the initial unification of Egypt under one ruler, supported by the general timing (as this is the period of the unification) and the fact that Narmer sports the crown connected to Upper Egypt on one face of the palette and the crown of Lower Egypt on the other—this is the first preserved example where both crowns are used by the same ruler. Other theories suggest that, rather than an actual historical representation, these scenes were purely ceremonial and related to the concept of unification in general.

Another interpretation: the sun and the king

More recent research on the decorative program has connected the imagery to the careful balance of order and chaos (known as ma’at and isfet) that was a fundamental element of the Egyptian idea of the cosmos. It may also be related to the daily journey of the sun god that becomes a central aspect in the Egyptian religion in the subsequent centuries.

The scene, showing Narmer wearing the Lower Egyptian Red Crown1 (with its distinctive curl), depicts him processing towards the decapitated bodies of his foes. The two rows of prone bodies are placed below an image of a high-prowed boat preparing to pass through an open gate. This may be an early reference to the journey of the sun god in his boat. In later texts, the Red Crown is connected with bloody battles fought by the sun god just before the rosy-fingered dawn on his daily journey and this scene may well be related to this. It is interesting to note that the foes are shown as not only executed, but rendered completely impotent—their castrated penises have been placed atop their severed heads.

On the other face, Narmer wears the Upper Egyptian White Crown* (which looks rather like a bowling pin) as he grasps an inert foe by the hair and prepares to crush his skull. The White Crown is related to the dazzling brilliance of the full midday sun at its zenith as well as the luminous nocturnal light of the stars and moon. By wearing both crowns, Narmer may not only be ceremonially expressing his dominance over the unified Egypt, but also the early importance of the solar cycle and the king’s role in this daily process.

This fascinating object is an incredible example of early Egyptian art. The imagery preserved on this palette provides a peek ahead to the richness of both the visual aspects and religious concepts that develop in the ensuing periods. It is a vitally important artifact of extreme significance for our understanding of the development of Egyptian culture on multiple levels.

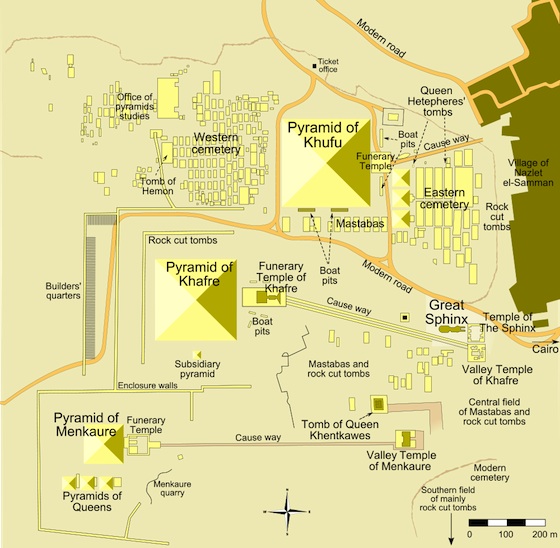

Old Kingdom: The Great Pyramids of Giza

One of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world

The last remaining of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, the great pyramids of Giza are perhaps the most famous and discussed structures in history. These massive monuments were unsurpassed in height for thousands of years after their construction and continue to amaze and enthrall us with their overwhelming mass and seemingly impossible perfection. Their exacting orientation and mind-boggling construction has elicited many theories about their origins, including unsupported suggestions that they had extra-terrestrial impetus. However, by examining the several hundred years prior to their emergence on the Giza plateau, it becomes clear that these incredible structures were the result of many experiments, some more successful than others, and represent an apogee in the development of the royal mortuary complex.

Three pyramids, three rulers

The three primary pyramids on the Giza plateau were built over the span of three generations by the rulers Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. Each pyramid was part of a royal mortuary complex that also included a temple at its base and a long stone causeway (some nearly 1 kilometer in length) leading east from the plateau to a valley temple on the edge of the floodplain.

Other (smaller) pyramids, and small tombs

In addition to these major structures, several smaller pyramids belonging to queens are arranged as satellites. A major cemetery of smaller tombs, known as mastabas (Arabic for ‘bench’ in reference to their shape—flat-roofed, rectangular, with sloping sides), fills the area to the east and west of the pyramid of Khufu and were constructed in a grid-like pattern for prominent members of the court. Being buried near the pharaoh was a great honor and helped ensure a prized place in the afterlife.

A reference to the sun

The shape of the pyramid was a solar reference, perhaps intended as a solidified version of the rays of the sun. Texts talk about the sun’s rays as a ramp the pharaoh mounts to climb to the sky—the earliest pyramids, such as the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara—were actually designed as a staircase. The pyramid was also clearly connected to the sacred ben-ben stone, an icon of the primeval mound that was considered the place of initial creation. The pyramid was considered a place of regeneration for the deceased ruler.

Construction

Many questions remain about the construction of these massive monuments, and theories abound as to the actual methods used. The workforce needed to build these structures is also still much discussed. Discovery of a town for workers to the south of the plateau has offered some answers. It is likely that there was a permanent group of skilled craftsmen and builders who were supplemented by seasonal crews of approximately 2,000 conscripted peasants. These crews were divided into gangs of 200 men, with each group further divided into teams of 20. Experiments indicate that these groups of 20 men could haul the 2.5 ton blocks from quarry to pyramid in about 20 minutes, their path eased by a lubricated surface of wet silt. An estimated 340 stones could be moved daily from quarry to construction site, particularly when one considers that many of the blocks (such as those in the upper courses) were considerably smaller.

Backstory (Dr. Naraelle Hohensee)

We are used to seeing the pyramids at Giza in alluring photographs, where they appear as massive and remote monuments rising up from an open, barren desert. Visitors might be surprised to find, then, that there is a golf course and resort only a few hundred feet from the Great Pyramid, and that the burgeoning suburbs of Giza (part of the greater metropolitan area of Cairo) have expanded right up to the foot of the Sphinx. This urban encroachment and the problems that come with it—such as pollution, waste, illegal activities, and auto traffic—are now the biggest threats to these invaluable examples of global cultural heritage.

The pyramids were inscribed into the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979, and since 1990, the organization has sponsored over a dozen missions to evaluate their status. It has supported the restoration of the Sphinx, as well as measures to curb the impact of tourism and manage the growth of the neighboring village. Still, threats to the site continue: air pollution from waste incineration contributes to the degradation of the stones, and the massive illegal quarrying of sand on the neighboring plateau has created holes large enough to be seen on Google Earth. Egypt’s 2011 uprisings and their chaotic political and economic aftermath also negatively impacted tourism, one of the country’s most important industries, and the number of visitors is only now beginning to rise once more.

UNESCO has continually monitored these issues, but its biggest task with regard to Giza has been to advocate for the rerouting of a highway that was originally slated to cut through the desert between the pyramids and the necropolis of Saqqara to the south. The government eventually agreed to build the highway north of the pyramids. However, as the Cairo metropolitan area (the largest in Africa, with a population of over 20 million) continues to expand, planners are now proposing a multilane tunnel to be constructed underneath the Giza Plateau. UNESCO and ICOMOS are calling for in-depth studies of the project’s potential impact, as well as an overall site management plan for the Giza pyramids that would include ways to halt the continued impact of illegal dumping and quarrying.

As massive as they are, the pyramids at Giza are not immutable. With the rapid growth of Cairo, they will need sufficient attention and protection if they are to remain intact as key touchstones of ancient history.

Video: The Mummification Process

The Getty Museum, “The Mummification Process.” https://youtu.be/-MQ5dL9cQX0

Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Sphinx

Size and appearance

The second great pyramid of Giza, that was built by Khufu’s second son Khafre, has a section of outer casing that still survives at the very top (and which would have entirely covered all three of the great pyramids at Giza). Although this monument appears larger than that of his father, it is actually slightly smaller but was constructed 10 m (33 feet) higher on the plateau.

Interior

The interior is much simpler than that of Khufu’s pyramid, with a single burial chamber, one small subsidiary chamber, and two passageways. The mortuary temple at the pyramid base was more complex than that of Khufu and was filled with statuary of the king–over 52 life-size or larger images originally filled the structure.

Valley temple

Khafre’s valley temple, located at the east end of the causeway leading from the pyramid base, is beautifully preserved. It was constructed of megalithic blocks sheathed with granite and floors of polished white calcite. Statue bases indicate that an additional 24 images of the pharaoh were originally located in this temple.

The Great Sphinx

Right next to the causeway leading from Khafre’s valley temple to the mortuary temple sits the first truly colossal sculpture in Egyptian history: the Great Sphinx. This close association indicates that this massive depiction of a recumbent lion with the head of a king was carved for Khafre.

The Sphinx is carved from the bedrock of the Giza plateau, and it appears that the core blocks used to construct the king’s valley temple were quarried from the layers of stone that run along the upper sides of this massive image.

Khafre

The lion was a royal symbol as well as being connected with the sun as a symbol of the horizon; the fusion of this powerful animal with the head of the pharaoh was an icon that survived and was often used throughout Egyptian history. The king’s head is on a smaller scale than the body. This appears to have been due to a defect in the stone; a weakness recognized by the sculptors who compensated by elongating the body.

Directly in front of the Sphinx is a separate temple dedicated to the worship of its cult, but very little is known about it since there are no Old Kingdom texts that refer to the Sphinx or its temple. The temple is similar to Khafre’s mortuary temple and has granite pillars forming a colonnade around a central courtyard. However, it is unique in that it has two sanctuaries—one on the east and one on the west—likely connected to the rising and setting sun.

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen

Serene ethereal beauty, raw royal power, and evidence of artistic virtuosity have rarely been simultaneously captured as well as in this breathtaking, nearly life-size statue of the pharaoh Menkaure and a queen. Smooth as silk, the meticulously finished surface of the dark stone captures the physical ideals of the time and creates a sense of eternity and immortality even today.

Undoubtedly, the most iconic structures from Ancient Egypt are the massive and enigmatic Great Pyramids that stand on a natural stone shelf, now known as the Giza plateau, on the south-western edge of modern Cairo. The three primary pyramids at Giza were constructed during the height of a period known as the Old Kingdom and served as burial places, memorials, and places of worship for a series of deceased rulers–the largest belonging to King Khufu, the middle to his son Khafre, and the smallest of the three to his son Menkaure.

Pyramids are not stand-alone structures. Those at Giza formed only a part of a much larger complex that included a temple at the base of the pyramid itself, long causeways and corridors, small subsidiary pyramids, and a second temple (known as a valley temple) some distance from the pyramid. These Valley Temples were used to perpetuate the cult of the deceased king and were active places of worship for hundreds of years (sometimes much longer) after the king’s death. Images of the king were placed in these temples to serve as a focus for worship—several such images have been found in these contexts, including the magnificent seated statue of Khafre, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

On January 10, 1910, excavators under the direction of George Reisner, head of the joint Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Expedition to Egypt, uncovered an astonishing collection of statuary in the Valley Temple connected to the Pyramid of Menkaure. Menkaure’s pyramid had been explored in the 1830s (using dynamite, no less). His carved granite sarcophagus was removed (and subsequently lost at sea), and while the Pyramid Temple at the base was in only mediocre condition; the Valley Temple, was—happily—basically ignored.

Reisner had been excavating on the Giza plateau for several years at this point; his team had already explored the elite cemetery to the west of the Great Pyramid of Khufu before turning their attention to the Menkaure complex, most particularly the barely-touched Valley Temple.

In the southwest corner of the structure, the team discovered a magnificent cache of statuary carved in a smooth-grained dark stone called greywacke or schist. There were a number of triad statues—each showing 3 figures—the king, the fundamentally important goddess Hathor, and the personification of a nome (a geographic designation, similar to the modern idea of a region, district, or county) (compare to Menkaure between Hathor and the personification of the nome of Thebes).

Hathor was worshiped in the pyramid temple complexes along with the supreme sun god Re and the god Horus, who was represented by the living king. The goddess’s name is actually ‘Hwt-hor’, which means “The House of Horus,” and she was connected to the wife of the living king and the mother of the future king. Hathor was also a fierce protector who guarded her father Re; as an “Eye of Re” (the title assigned to a group of dangerous goddesses), she could embody the intense heat of the sun and use that blazing fire to destroy his enemies

There were four complete triads, one incomplete, and at least one other in a fragmentary condition. The precise meaning of these triads is uncertain. Reisner believed that there was one for each ancient Egyptian nome, meaning there would have originally been more than thirty of them. More recent scholarship, however, suggests that there were originally 8 triads, each connected with a major site associated with the cult of Hathor. Hathor’s prominence in the triads (she actually takes the central position in one of the sculptures) and her singular importance to kingship lends weight to this theory.

In addition to the triads, Reisner’s team also revealed the extraordinary dyad statue of Menkaure and a queen that is breathtakingly singular.

The two figures stand side-by-side on a simple, squared base and are supported by a shared back pillar. They both face to the front, although Menkaure’s head is noticeably turned to his right—this image was likely originally positioned within an architectural niche, making it appear as though they were emerging from the structure. The broad-shouldered, youthful body of the king is covered only with a traditional short pleated kilt, known as a shendjet, and his head sports the primary pharaonic insignia of the iconic striped nemes headdress (so well known from the mask of Tutankhamun) and an artificial royal beard. In his clenched fists, held straight down at his sides, Menkaure grasps ritual cloth rolls. His body is straight, strong, and eternally youthful with no signs of age. His facial features are remarkably individualized with prominent eyes, a fleshy nose, rounded cheeks, and full mouth with protruding lower lip.

Menkaure’s queen provides the perfect female counterpart to his youthful masculine virility. Sensuously modeled with a beautifully proportioned body emphasized by a clinging garment, she articulates ideal mature feminine beauty. There is a sense of the individual in both faces. Neither Menkaure nor his queen are depicted in the purely idealized manner that was the norm for royal images. Instead, through the overlay of royal formality we see the depiction of a living person filling the role of pharaoh and the personal features of a particular individual in the representation of his queen.

Menkaure and his queen stride forward with their left feet—this is entirely expected for the king, as males in Egyptian sculpture almost always do so, but it is unusual for the female since they are generally depicted with feet together. They both look beyond the present and into timeless eternity, their otherworldly visage displaying no human emotion whatsoever.

The dyad was never finished—the area around the lower legs has not received a final polish, and there is no inscription. However, despite this incomplete state, the image was erected in the temple and was brightly painted—there are traces of red around the king’s ears and mouth and yellow on the queen’s face. The presence of paint atop the smooth, dark greywacke on a statue of the deceased king that was originally erected in his memorial temple courtyard brings an interesting suggestion—that the paint may have been intended to wear away through exposure and, over time, reveal the immortal, black-fleshed “Osiris” Menkaure.

Unusual for a pharaoh’s image, the king has no protective cobra (known as a uraeus) perched on his brow. This notable absence has led to the suggestion that both the king’s nemes and the queen’s wig were originally covered in precious metal and that the cobra would have been part of that addition.

Based on comparison with other images, there is no doubt that this sculpture shows Menkaure, but the identity of the queen is a different matter. She is clearly a royal female. She stands at nearly equal height with the king and, of the two of them, she is the one who is entirely frontal. In fact, it may be that this dyad is focused on the queen as its central figure rather than Menkaure. The prominence of the royal female—at equal height and frontal—in addition to the protective gesture she extends has suggested that, rather than one of Mekaure’s wives, this is actually his queen-mother. The function of the sculpture in any case was to ensure rebirth for the king in the Afterlife.

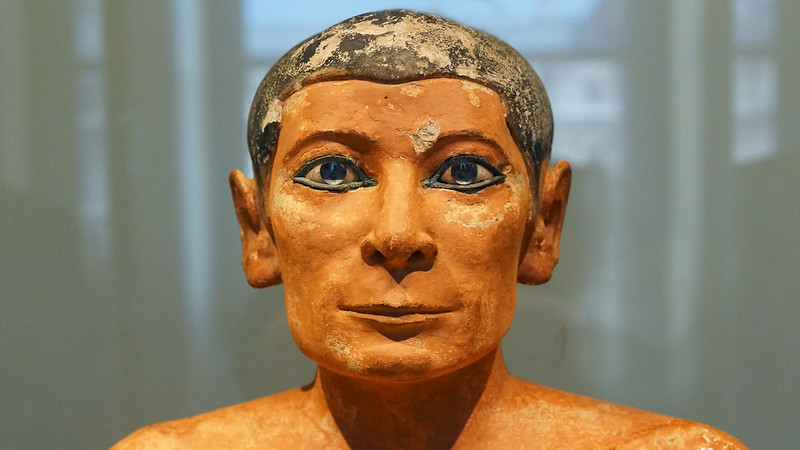

Seated Scribe from Saqqara: A CONVERSATION

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Musee du Louvre, Paris. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/IKkcop-dlUY

Steven: We’re in the Egyptian Collection in the Louvre, in Paris, and we’re looking at the Seated Scribe. uis goes back to the Old Kingdom.

Beth: So this is more than 4,000, almost 5,000 years old, and what draws people to this relatively small sculpture is how lifelike it is, given how old it is.

Steven: It’s painted, which adds to its lifelike quality.

Beth: And that was not unusual for ancient Egyptian sculpture, although the amount of pigment and coloration that survives here is rather unique.

Steven: With a few exceptions, the sculpture is painted limestone. The exceptions are the nipples, which are wooden dowels, and the eyes.

Beth: The eyes are incredibly lifelike.

Steven: And that’s because they’re made of two different types of stone: crystal, which is polished on the front, and then an organic material is added to the back that functions both as an adhesive but also to color the iris. And there’s also an indentation carved to represent the pupil. All of this comes together to create a sense of alertness, a sense of awareness, a sense of intelligence, that is quite present. It collapses the 4,500 years between when the sculpture was made and today.

Beth: He’s not idealized the way that we would see a figure of a pharaoh—the Egyptians considered pharaohs to be gods and would never have represented the pharaoh in this relaxed, cross-legged position and with the rolls of fat that help make him more human.

Steven: He looks so relaxed, almost like he’s just exhaled.

Beth: That’s true, but there is also a real formality here. He’s very frontal. He’s meant to be seen—pretty much exclusively—from the front and there’s almost a complete symmetry to his body.

Steven: The exception being his hands. His right would have originally held a brush or a pen and his left holds a rolled piece of papyrus that he’s writing on, which is interesting because it suggests the momentary even though the Egyptians are so concerned with the eternal. You said a moment ago that he’s intended to be seen from the front, but that raises an interesting question: Was this sculpture meant to be seen at all?

Beth: Well, he was found in a necropolis southwest of Cairo in a place called Saqqara, an important Old Kingdom necropolis, and we don’t know his exact findspot, so we don’t know as much about him as we would have if we did. But you’re right, this is a funerary sculpture meant for a tomb.

Steven: We would know more about him if the base on which he sits was not cut. It probably would have originally included his name and his titles.

Beth: What’s interesting is that the hieroglyph for “scribe” is quite pictographic and shows a writing instrument—a pen, a pot of water, and cakes of pigment. Scribes were very highly regarded in Egyptian culture. They were one of the very few people who could read and write. It’s impossible to know how much of a portrait this is because we don’t have this man in front of us, we don’t know the degree to which this sculpture resembles him.

Steven: The sculpture’s been carved with real delicacy. The fingers are long and elegant, the fingernails are carefully inscribed.

Beth: And he has very pronounced high cheekbones.

Steven: The only clothing he wears is a kilt, which has been painted white. His skin is a pretty rich red-brown, and the hair and the rims of his eyes are accentuated with black.

Beth: It is wonderful to have this sculpture reaching out to us from more than 4,000 years ago.

Middle Kingdom Egypt: Senusret III & Block Statues

By Lumen Learning, Boundless Art History

During the Middle Kingdom, relief and portrait sculpture captured subtle, individual details that reached new heights of technical perfection. Some of the finest examples of sculpture during this time was at the height of the empire under Pharaoh Senusret III.

Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or Sesostris III) ruled from 1878–1839 BCE and was the fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. His military campaigns gave rise to an era of peace and economic prosperity that not only reduced the power of regional rulers, but also led to a revival in craftwork, trade, and urban development in the Egyptian kingdom. One of the few kings who were deified and honored with a cult during their own lifetime, he is considered to be perhaps the most powerful Egyptian ruler of the dynasty.

Aside from his accomplishments in architecture and war, Senusret III is known for his strikingly somber sculptures in which he appears careworn and grave. Deviating from the standard way of representing kings, Senusret III and his successor Amenemhat III had themselves portrayed as mature, aging men. This is often interpreted as a portrayal of the burden of power and kingship. The change in representation as ideological, and not something to be interpreted as the portrayal of an aging king, is shown by the fact that in one single relief, Senusret III was represented as a vigorous young man, following the centuries old tradition, and as a mature aging king.

Block Statues and Women Patrons

Another important innovation in sculpture that occurred during the Middle Kingdom was the block statue, which would continue to be popular through to the Ptolemaic age almost 2,000 years later. Block statues consist of a man squatting with his knees drawn up to his chest and his arms folded on top of his knees. Often, these men are wearing a wide cloak that reduces the body of the figure to a simple block-like shape. In some cases the cloak covers the feet completely, and in others the feet are left uncovered. The head of the sculpture contains the most detail.

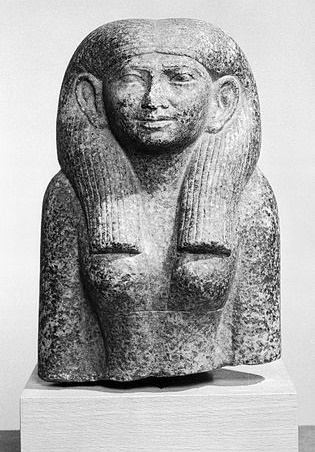

The sculpture pictured below—the fact that a private woman could have a sculpture made for herself—speaks volumes for the equality of gender in ancient Egypt. The heavy tripartite wig frames the broad face and passes behind the ears, thus giving the impression of forcing them forward. They are large in keeping with the ancient Egyptian ideal of beauty; the same ideal required small breasts, and in this respect, the sculpture is no exception. Whereas the natural curve of the eyebrows dips towards the root of the nose, the artificial eyebrows in low relief are absolutely straight above the inner corners of the eyes, a feature which places the bust early in the early Twelfth Dynasty. Around 1900 BCE, these artificial eyebrows, too, began to follow the natural curve and dipped toward the nose.

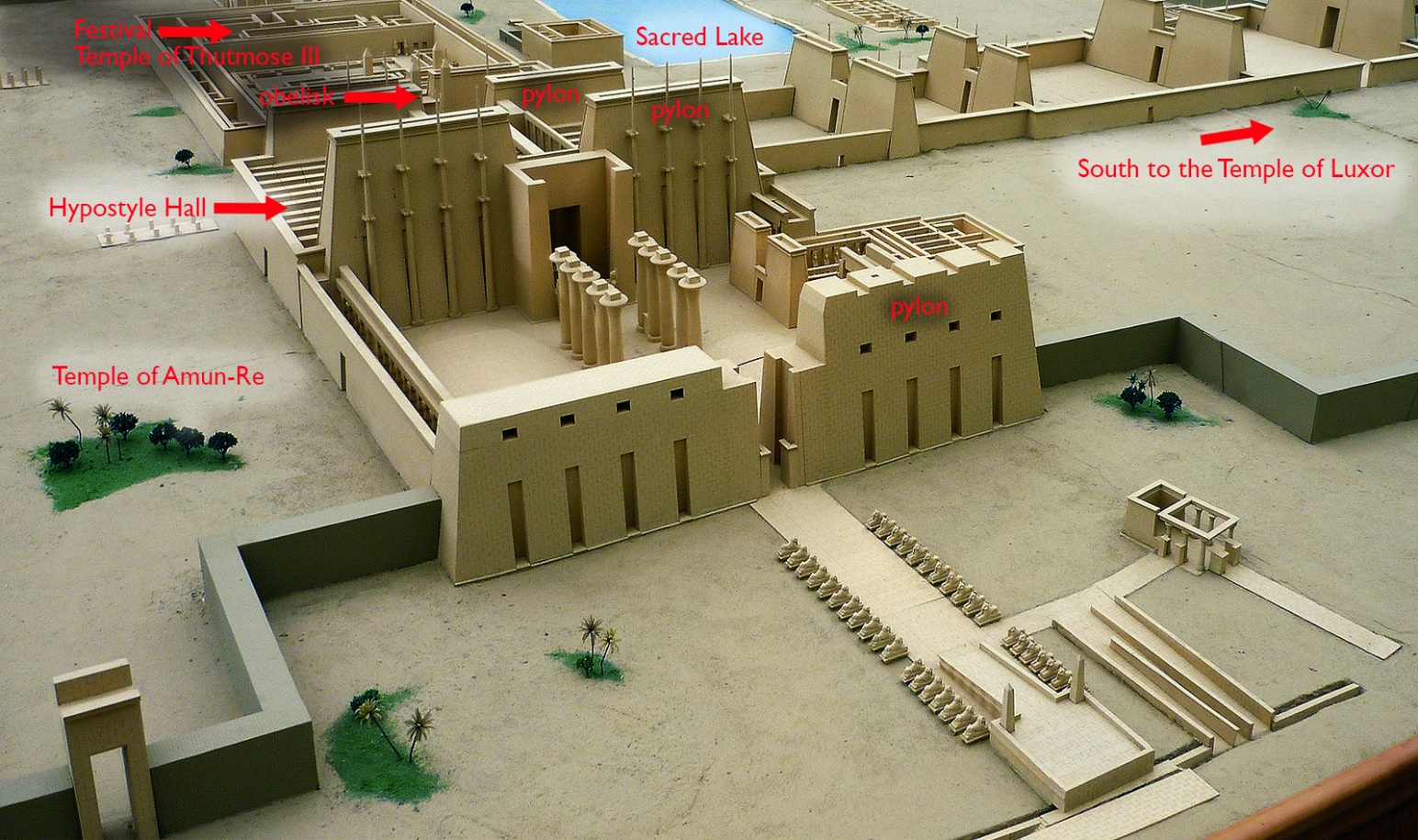

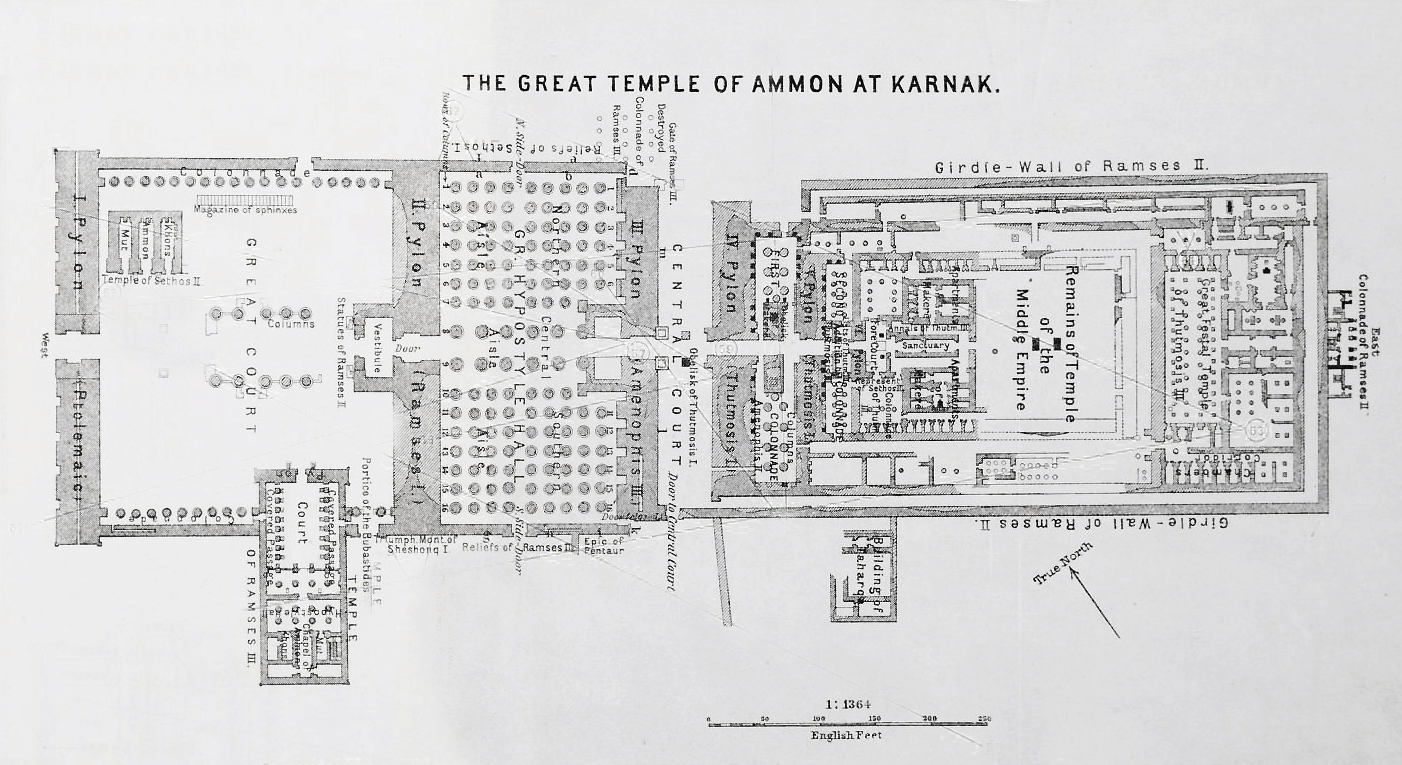

New Kingdom: Temple of Amun-Re and the Hypostyle Hall, Karnak

The massive temple complex of Karnak was the principal religious center of the god Amun-Re in Thebes during the New Kingdom (which lasted from 1550 until 1070 B.C.E.). The complex remains one of the largest religious complexes in the world. However, Karnak was not just one temple dedicated to one god—it held not only the main precinct to the god Amun-Re—but also the precincts of the gods Mut and Montu. Compared to other temple compounds that survive from ancient Egypt, Karnak is in a poor state of preservation but it still gives scholars a wealth of information about Egyptian religion and art.

“The Most Select of Places”

The site was first developed during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 B.C.E.) and was initially modest in scale but as new importance was placed on the city of Thebes, subsequent pharaohs began to place their own mark on Karnak. The main precinct alone would eventually have as many as twenty temples and chapels.1 Karnak was known in ancient times as “The Most Select of Places” (Ipet-isut) and was not only the location of the cult image of Amun and a place for the god to dwell on earth but also a working estate for the priestly community who lived on site. Additional buildings included a sacred lake, kitchens, and workshops for the production of religious accoutrements.

The main temple of Amun-Re had two axes—one that went north/south and the other that extended east/west. The southern axis continued towards the temple of Luxor and was connected by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes.

While the sanctuary was plundered for stone in ancient times, there are still a number of unique architectural features within this vast complex. For example, the tallest obelisk in Egypt stood at Karnak and was dedicated by the female pharaoh Hatshepsut who ruled Egypt during the New Kingdom. Made of one piece of red granite, it originally had a matching obelisk that was removed by the Roman emperor Constantine and re-erected in Rome. Another unusual feature was the Festival Temple of Thutmose III, which had columns that represented tent poles, a feature this pharaoh was no doubt familiar with from his many war campaigns.

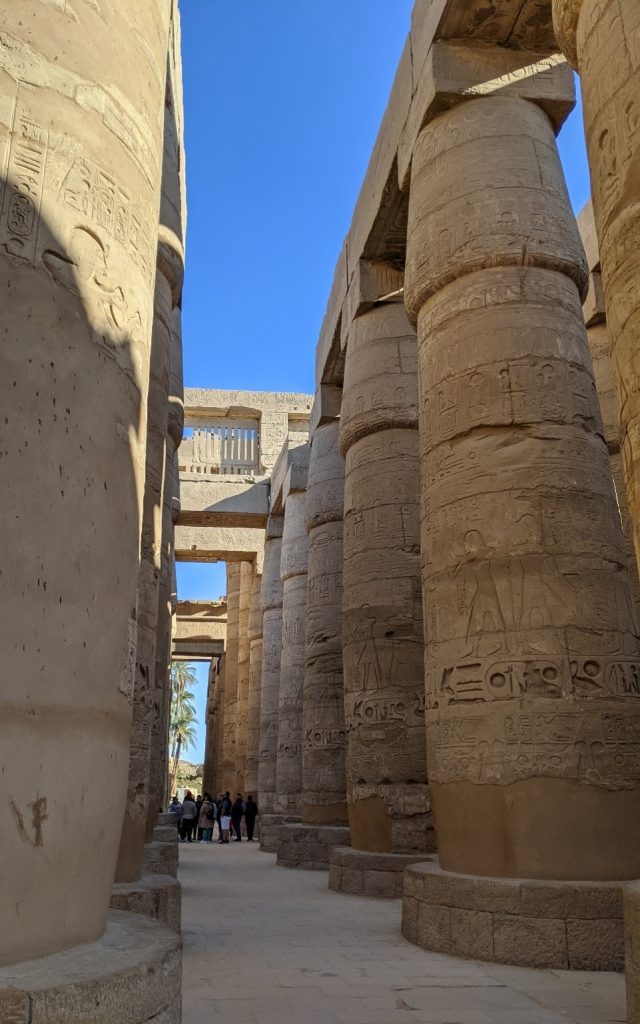

Hypostyle hall

One of the greatest architectural marvels of Karnak is the hypostyle hall built during the Ramesside period (a hypostyle hall is a space with a roof supported by columns). The hall has 134 massive sandstone columns with the center twelve columns standing at 69 feet. Like most of the temple decoration, the hall would have been brightly painted and some of this paint still exists on the upper portions of the columns and ceiling today. With the center of the hall taller than the spaces on either side, the Egyptians allowed for clerestory lighting (a section of wall that allowed light and air into the otherwise dark space below). In fact, the earliest evidence for clerestory

lighting comes from Egypt. Not many ancient Egyptians would have had access to this hall, since the further one went into the temple, the more restricted access became.

Temple as cosmos

Conceptually, temples in Egypt were connected to the idea of zep tepi, or “the first time,” the beginnings of the creation of the world. The temple was a reflection of this time, when the mound of creation emerged from the primeval waters. The pylons, or gateways in the temple represent the horizon, and as one moves further into the temple, the floor rises until it reaches the sanctuary of the god, giving the impression of a rising mound, like that during creation. The temple roof represented the sky and was often decorated with stars and birds. The columns were designed with lotus, papyrus, and palm plants in order to reflect the marsh-like environment of creation. The outer areas of Karnak, which was located near the Nile River, would flood during the annual inundation—an intentional effect by the ancient designers no doubt, in order to enhance the temple’s symbolism.2

The Valley of the Kings

By Lumen Learning, Boundless Art History

By this time, pyramids were no longer built by kings, but they continued to build magnificent tombs. This renowned valley in Egypt is where, for a period of nearly 500 years, tombs were constructed for the Pharaohs and powerful nobles of the New Kingdom. The valley is known to contain 63 tombs and chambers, the most well known of which is the tomb of Tutankhamun (commonly known as King Tut). Despite its small size, it is the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. In 1979, the Valley became a World Heritage Site, along with the rest of the Theban Necropolis .

Hatshepsut

The Temple of Hatshepsut was Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple and was the first to be built in the area. The focal point of the tomb was the Djeser-Djeseru, a colonnaded structure of perfect harmony that predates the Parthenon by nearly one thousand years. Built into a cliff face, Djeser-Djeseru, or “the Sublime of Sublimes,” sits atop a series of terraces that once were graced with lush gardens. Funerary goods belonging to Hatshepsut include a lioness “throne,” a game board with carved lioness head, red-jasper game pieces bearing her title as pharaoh, a signet ring, and a partial shabti figurine bearing her name.

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut: A CONVERSATION

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/pZOUV_rTyj0.

Steven: We’re in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in the section devoted to the art of Ancient Egypt. And we’re looking at an enormous, granite sculpture.

Beth: This is a sculpture of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut.

Steven: We think of pharaohs, that is, ancient Egyptian kings, as male. And of course, the vast majority were. There had been a long tradition in ancient Egypt of women assuming enormous authority in the position of regent, that is as a mother or a member of the royal family who would reign until a male ruler reached the age where they could actually assume power.

Beth: Those women were very powerful but Hatshepsut is unusual. She assumes the authority of king, of pharaoh. She created a whole mythology around her kingship that described her divine birth, the way that an oracle had predicted that she would become king. She ruled Egypt for more than two decades. She commissioned a remarkable number of temples, of sculptures. She was interested in the power of art to convey royal authority.

Steven: And no building speaks to the authority of the king more than the mortuary temple.

Beth: The sculpture that we’re looking at was actually made for this mortuary temple. There anywhere from six or eight or ten of these kneeling figures. There were also representations of Hatshepsut as a sphinx which lined the center of the lower courtyard of her mortuary temple.

Steven: And that temple is an extraordinary place. It is built directly against this vast cliff face.

Beth: I can’t think of a more dramatic environment for architecture. Those cliff are towering and their organic qualities are in such contrast to the regular order and structure of the built environment.

Steven: This is hewn right from the living rock.

Beth: And that sense of permanence, that sense of stability that is expressed by that wall of living rock is a perfect expression of the very sense of stability that we think Hatshepsut and her dynasty were trying to reassert after a period of instability. This was the beginning of the New Kingdom.

Steven: In ancient Egyptian history, we talk about three major periods: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom, and these periods are separated by periods we call Intermediate Periods.

Beth: These were periods of relative chaos, often when Egypt was divided in its rule or was ruled by external rulers.

Steven: The representations of kingship in ancient Egyptian art are almost two millennia old by the time we get to Hatshepsut and so what she can do is adopt those forms to show herself as king. These forms were easily recognizable. That is symmetry, its embeddedness in the stone, we see that there is no space between her arms and her torso or between her legs. There is a real sense of timelessness but there are also more specific symbols.

Beth: The headcloth that she wears is a symbol of the king that would have originally been a cobra.

Steven: We have the beard that we associate with kingship.

Beth: We’re talking about a visual language here. And this visual language of kingship was male. In fact, there is no word for queen in the Egyptian language. The term is king’s wife, or king’s mother.

Steven: Her body is represented in a relatively masculine way. Her breasts are deemphasized, for example. She has broad shoulders.

Beth: The inscriptions that were on many of these sculptures use a feminine form and so the representation itself is masculine but the identifying words, the hieroglyphs identify her as female. About 20 years after Hatshepsut died, the pharaoh she had been co-ruler with systematically destroyed all images of Hatshepsut.

Steven: That would not have been an easy matter. You wouldn’t have simply toppled the sculpture. It would have shattered into so many pieces. This made of granite, incredibly hard stone. It would have been very difficult to produce and it would have been very difficult to destroy.

Beth: Well, and not only that but Hatshepsut had commissioned hundreds of images of herself. So it would have taken a long time to destroy these sculptures. This was an intentional act, but we’re not really sure why this happened.

Steven: We do know that the fragments were discovered in the early twentieth-century thanks to an excavation undertaken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art which is why they are here. And what we’re seeing is a series of monumental sculptures that have been put back together but some of this is guesswork. We don’t know if one particular fragment goes with one sculpture versus another.

Beth: So when we look at those sculptures, we see her in a range of positions. In some, she is kneeling. In some, she is standing. In some, she is seated. In some, she is represented as a sphinx. A king only would kneel of course to a god. That really helps us place this sculpture along the processional path.

Steven: So once a year, there was a ritual involving a sculpture of a god. Now we have to remember that for Egyptians, the sculpture of the god was the embodiment of the god and temples were houses for a god. So once a year the sculpture of the primary god, Amun-Re, was taken from the temple in Thebes on the eastern side of the Nile.

Beth: And carried across the river on a ceremonial barque, on a shrine that was shaped like a boat.

Steven: As though he were traveling literally across the Nile from the eastern side, the land of the living, toward the land of the dead, and he would be carried up this causeway toward the temple and his primary shrine in the mortuary temple at the very top center.

Beth: And that sculpture would have been spent one night in that shrine before it would have been returned across the river.

Steven: And so it makes sense then that you would have this representation of Hatshepsut on her knees making an offering, these two bowls or jars that she holds are an offering to the god because the god passed in front of these sculptures who are not just sculptures but embodiments of Hatshepsut.

Beth: It’s interesting how the scholarship that surrounds this ruler has changed. Early in the twentieth century, for example, the destruction of the images of this ruler was associated with the idea that she was out of place, that she was a usurper, and she was seen very much in a negative light. She is seen much more sympathetically now, in the early twenty-first century.

Steven: And there were women before Hatshepsut who asserted themselves as kings, and there were a few women after her, but Hatshepsut had enormous power, enormous influence, the sculptures, the architecture that she commissioned set an important standard and inspiration for all the later work of the New Kingdom. Imagine walking past these enormous sculptures of Hatshepsut.

Beth: This is all about the procession. This is all about pageantry. This is all about expressing power as the king.

Steven: Kneeling like this is not something you can do for more than a minute or two. It’s hard on the toes. It’s hard on the knees. So this is a position that someone would only take very temporarily and yet there is something very eternal about the sculpture, something very permanent. This is not a figure who engages us, who is in the world, but who lives in the eternal. This is an image of a king who is also a god.

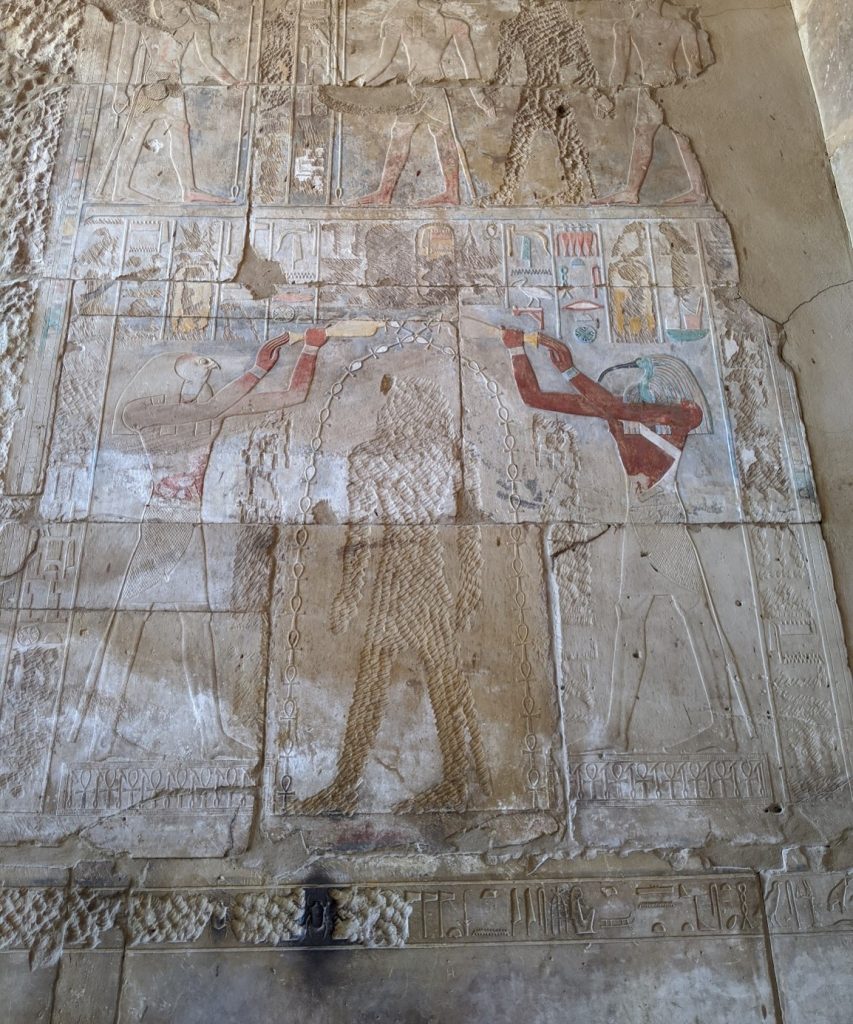

Paintings from the Tomb-chapel of Nebamun

The fragments from the wall painting in the tomb-chapel of Nebamun are keenly observed vignettes of Nebamun and his family enjoying both work and play. Some concern the provision of the funerary cult that was celebrated in the tomb-chapel, some show scenes of Nebamun’s life as an elite official, and others show him and his family enjoying life for all eternity, as in the famous scene of the family hunting in the marshes. Together they decorated the small tomb-chapel with vibrant and engaging images of an elite lifestyle that Nebamun hoped would continue in the afterlife.

Hunting in the marshes

Nebamun is shown hunting birds from a small boat in the marshes of the Nile with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter. Such scenes had already been traditional parts of tomb-chapel decoration for hundreds of years and show the dead tomb-owner “enjoying himself and seeing beauty,” as the hieroglyphic caption here says.

This is more than a simple image of recreation. Fertile marshes were seen as a place of rebirth and eroticism. Hunting animals could represent Nebamun’s triumph over the forces of nature as he was reborn. The huge striding figure of Nebamun dominates the scene, forever happy and forever young, surrounded by the rich and varied life of the marsh.

There was originally another half of the scene which showed Nebamun spearing fish. This half of the wall is lost, apart from two old photographs of small fragments of Nebamun and his young son. The painters have captured the scaly and shiny quality of the fish.

A tawny cat catches birds among the papyrus stems. Cats were family pets, but in artistic depictions like this they could also represent the Sun-god hunting the enemies of light and order. His unusual gilded eye hints at the religious meanings of this scene.

The artists have filled every space with lively details. The marsh is full of lotus flowers and Plain Tiger butterflies. They are freely and delicately painted, suggesting the pattern and texture of their wings.

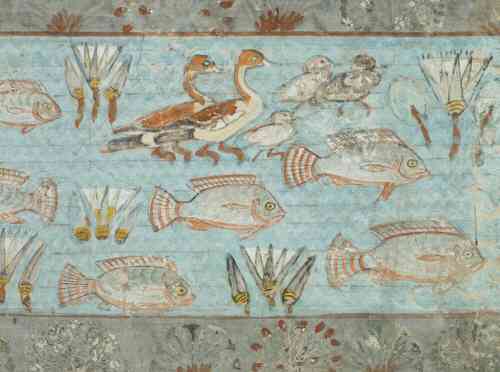

Nebamun’s Garden

Nebamun’s garden in the afterlife is not unlike the earthly gardens of wealthy Egyptians. The pool is full of birds and fish, and surrounded by borders of flowers and shady rows of trees. The fruit trees include sycamore-figs, date-palms and dom-palms—the dates are shown with different degrees of ripeness.

On the right side of the pool a goddess leans out of a tree and offers fruit and drinks to Nebamun (now lost). The artists accidentally painted her skin red at first but then repainted it yellow, the correct color for a goddess’ skin. On the left, a sycamore-fig tree speaks and greets Nebamun as the owner of the garden; its words are recorded in the hieroglyphs.Here the pool is shown from above, with three rows of trees arranged around its edges. The waves of the pool were painted with a darker blue pigment; much of this has been lost, like the green on the trees and bushes.

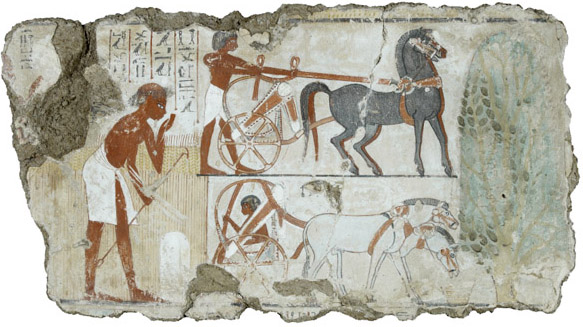

Surveying the fields

Nebamun was the accountant in charge of grain at the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. This scene from his tomb-chapel shows officials inspecting fields. A farmer checks the boundary marker of the field.

Nearby, two chariots for the party of officials wait under the shade of a sycamore-fig tree. Other smaller fragments from this wall are now in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, Germany and show the grain being harvested and processed.

The old farmer is shown balding, badly shaven, poorly dressed, and with a protruding navel. He is taking an oath saying: “As the Great God who is in the sky endures, the boundary-stone is exact!”

“The Chief of the Measurers of the Granary,” (mostly lost) holds a rope decorated with the head of Amun’s sacred ram for measuring the god’s fields. After Nebamun died, the rope’s head was hacked out, but later, perhaps in Tutankhamun’s reign, someone clumsily restored it with mud-plaster and redrew it.

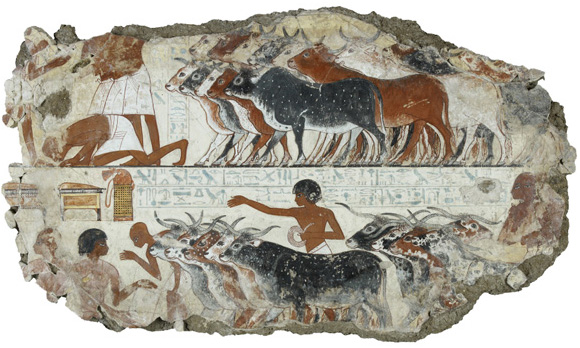

Nebamun’s cattle

This fragment is part of a wall showing Nebamun inspecting flocks of geese and herds of cattle. Hieroglyphs describe the scene and record what the farmers say as they squabble in the queue. The alternating colors and patterns of cattle create a superb sense of animal movement.

The herdsman is telling the farmer in front of him in the queue:

Come on! Get away! Don’t speak in the presence of the praised one! He detests people talking …. Pass on in quiet and in order … He knows all affairs, does the scribe and counter of grain of [Amun], Neb[amun].

The name of the god Amun has been hacked out in this caption where it appears in Nebamun’s name and title. Shortly after Nebamun died, King Akhenaten (1352–1336 B.C.E.) had Amun’s name erased from monuments as part of his religious reforms.

Nebamun’s geese

This scene is part of a wall showing Nebamun inspecting flocks of geese and herds of cattle. He watches as farmers drive the animals towards him; his scribes (secretaries) write down the number of animals for his records. Hieroglyphs describe the scene and record what the farmers say as they squabble in the queue.

This scribe holds a palette (pen-box) under his arm and presents a roll of papyrus to Nebamun. He is well dressed and has small rolls of fat on his stomach, indicating his superior position in life. Beside him are chests for his records and a bag containing his writing equipment.

Farmers bow down and make gestures of respect towards Nebamun. The man behind them holds a stick and tells them: “Sit down and don’t speak!” The farmers’ geese are painted as a huge and lively gaggle, some pecking the ground and some flapping their wings.

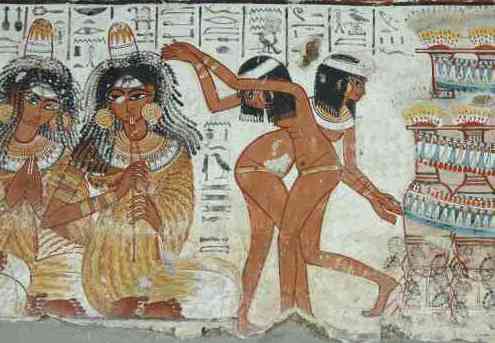

A feast for Nebamun (top half)

An entire wall of the tomb-chapel showed a feast in honor of Nebamun. Naked serving-girls and servants wait on his friends and relatives. Married guests sit in pairs on fine chairs, while the young women turn and talk to each other. This erotic scene of relaxation and wealth is something for Nebamun to enjoy for all eternity. The richly-dressed guests are entertained by dancers and musicians, who sit on the ground playing and clapping. The words of their song in honor of Nebamun are written above them:

The earth-god has caused

his beauty to grow in every body…

the channels are filled with water anew,

and the land is flooded with love of him.

Some of the musicians look out of the paintings, showing their faces frontally. This is very unusual in Egyptian art, and gives a sense of liveliness to these lower-class women, who are less formally drawn than the wealthy guests. The young dancers are sinuously drawn and are naked apart from their jewelry.

A rack of large wine jars is decorated with grapes, vines and garlands of flowers. Many of the guests also wear garlands and smell lotus flowers. All the guests wear elaborate linen clothes. The artists have painted the cloth as if it were transparent, to show that it is very fine. These elegant sensual dresses fall in loose folds around the guests’ bodies.

Men and women’s skins are painted in different colors: the men are tanned and the women are paler. In one place the artists altered the drawing of these wooden stools and corrected their first sketch with white paint.

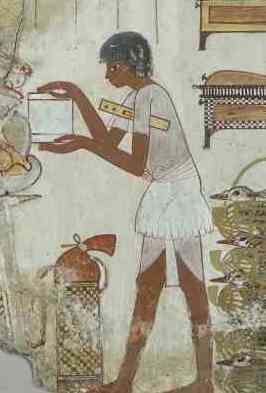

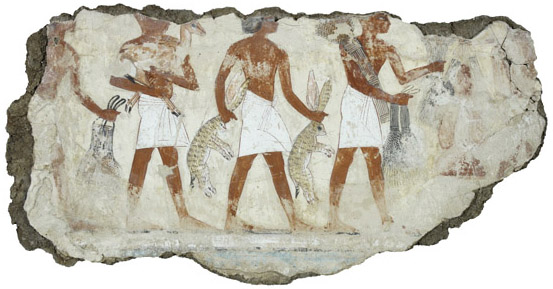

Servants bringing offerings

A procession of simply-dressed servants bring offerings of food to Nebamun, including sheaves of grain and animals from the desert. Tomb-chapels were built so that people could come and make offerings in memory of the dead, and this a common scene on their walls. The border at the bottom shows that this scene was the lowest one on this wall.

One servant holds two desert hares by their ears. The animals have wonderfully textured fur and long whiskers. The superb draughtsmanship and composition make this standard scene very fresh and lively.

The artists have even varied the servants’ simple clothes. The folds of each kilt are different. With one of these kilts, the artist changed his mind and painted a different set of folds over his first version, which is visible through the white paint.

Amarna Period: Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters (a conversation)

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/ryycDVWXDvc.

Steven: So around 1350 B.C.E., everything changed in Egyptian art.

Beth: When we think about Egyptian art, we don’t think of change.

Steven: That’s true. The Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, and the transitional periods between—art is consistent for almost 3,000 years. But there is this radical break right around 1350. And it’s because the ruler, Akhenaten, changes the state religion.

Beth: He changes it from the worship of the god Amun to a new god, a sun god, called Aten. So he actually changes his own name to Akhenaten, which means Aten is pleased. The key is he makes him and his wife the only representatives of Aten on earth. And so he upsets the entire priesthood of Egypt by making him and his wife the only ones with access to this new god, Aten.

Steven: And in fact, after Akhenaten dies, Egypt will return to its traditional religion. So this period is a very brief episode in Egyptian history, but it also marks a real shift in style. And this small stone plaque that we’re looking at, this sunken relief carving—which would have been placed in a private domestic environment—is a perfect example of those stylistic changes.

Beth: Right. It would have been an altar in someone’s home, where they would have seen Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti and their relationship to the god Aten. This has always been one of my favorite sculptures. It’s so informal, compared to most Egyptian art. We really have a sense of a couple and their relationship with one another and their relationship with their children. And love and domesticity.

Steven: So let’s take a close look. On the left, you have Akhenaten himself. This is the pharaoh of Egypt, the supreme ruler. You can see that he’s holding his eldest daughter, and he’s actually getting ready to kiss her. He seems to be holding her very tenderly, supporting her head, holding her under the thighs. She seems to be, perhaps, pointing back to her mother at the same moment.