4

Dr. Beth Harris; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Bryan Zygmont; Dr. Senta German; and Mary Beth Looney

In this chapter

Paleolithic Art

Neolithic Art

Paleolithic art, an introduction

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

The oldest art: ornamentation

Humans make art. We do this for many reasons and with whatever technologies are available to us. Extremely old, non-representational ornamentation has been found across Africa. The oldest firmly-dated example is a collection of 82,000 year old Nassarius snail shells found in Morocco that are pierced and covered with red ochre. Wear patterns suggest that they may have been strung beads. Nassarius shell beads found in Israel may be more than 100,000 years old and in the

Blombos cave in South Africa, pierced shells and small pieces of ochre (red Haematite) etched with simple geometric patterns have been found in a 75,000-year-old layer of sediment.

The oldest representational art

The oldest known representational imagery comes from the Aurignacian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period (Paleolithic means old stone age). Archaeological discoveries across a broad swath of Europe (especially Southern France, Northern Spain, and Swabia, in Germany) include over two hundred caves with spectacular Aurignacian paintings, drawings and sculpture that are among the earliest undisputed examples of representational image-making. The oldest of these is a 2.4-inch tall female figure carved out of mammoth ivory that was found in six fragments in the Hohle Fels cave near Schelklingen in southern Germany. It dates to 35,000 B.C.E.

The caves

The caves at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, Lascaux, Pech Merle, and Altamira contain the best known examples of pre-historic painting and drawing. Here are remarkably evocative renderings of animals and some humans that employ a complex mix of naturalism and abstraction. Archaeologists that study Paleolithic era humans, believe that the paintings discovered in 1994, in the cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc in the Ardéche valley in France, are more than 30,000 years old. The images found at Lascaux and Altamira are more recent, dating to approximately 15,000 B.C.E. The paintings at Pech Merle date to both 25,000 and 15,000 B.C.E.

Questions

What can we really know about the creators of these paintings and what the images originally meant? These are questions that are difficult enough when we study art made only 500 years ago. It is much more perilous to assert meaning for the art of people who shared our anatomy but had not yet developed the cultures or linguistic structures that shaped who we have become. Do the tools of art history even apply? Here is evidence of a visual language that collapses the more than 1,000 generations that separate us, but we must be cautious. This is especially so if we want to understand the people that made this art as a way to understand ourselves. The desire to speculate based on what we see and the physical evidence of the caves is wildly seductive.

Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc

The cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc is over 1,000 feet in length with two large chambers. Carbon samples date the charcoal used to depict the two head-to-head Rhinoceroses (see the image above, bottom right) to between 30,340 and 32,410 years before 1995 when the samples were taken. The cave’s drawings depict other large animals including horses, mammoths, musk ox, ibex, reindeer, aurochs, megaceros deer, panther, and owl (scholars note that these animals were not then a normal part of people’s diet). Photographs show that the drawing shown above is very carefully rendered but may be misleading. We see a group of horses, rhinos and bison and we see them as a group, overlapping and skewed in scale. But the photograph distorts the way these animal figures would have been originally seen. The bright electric lights used by the photographer create a broad flat scope of vision; how different to see each animal emerge from the dark under the flickering light cast by a flame.

A word of caution

In a 2009 presentation at University of California San Diego, Dr. Randell White, Professor of Anthropology at New York University, suggested that the overlapping horses pictured above might represent the same horse over time, running, eating, sleeping, etc. Perhaps these are far more sophisticated representations than we have imagined. There is another drawing at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc that cautions us against ready assumptions. It has been interpreted as depicting the thighs and genitals of a woman but there is also a drawing of a bison and a lion, and the images are nearly intertwined. In addition to the drawings, the cave is littered with the skulls and bones of cave bear and the track of a wolf. There is also a footprint thought to have been made by an eight-year-old boy.

Woman of Willendorf

The name of this prehistoric sculpture refers to a Roman goddess—but what did she originally represent?

Can a 25,000-year-old object be a work of art?

The artifact known as the Venus of Willendorf dates to between 24,000-22,000 B.C.E., making it one of the oldest and most famous surviving works of art. But what does it mean to be a work of art?

The Oxford English Dictionary, perhaps the authority on the English language, defines the word “art” as

the application of skill to the arts of imitation and design, painting, engraving, sculpture, architecture; the cultivation of these in its principles, practice, and results; the skillful production of the beautiful in visible forms.

Some of the words and phrases that stand out within this definition include “application of skill,” “imitation,” and “beautiful.” By this definition, the concept of “art” involves the use of skill to create an object that contains some appreciation of aesthetics. The object is not only made, it is made with an attempt of creating something that contains elements of beauty.

In contrast, the same Oxford English Dictionary defines the word “artifact” as, “anything made by human art and workmanship; an artificial product. In Archaeol[ogy] applied to the rude products of aboriginal workmanship as distinguished from natural remains.” Again, some key words and phrases are important: “anything made by human art,” and “rude products.” Clearly, an artifact is any object created by humankind regardless of the “skill” of its creator or the absence of “beauty.”

Artifact, then, is anything created by humankind, and art is a particular kind of artifact, a group of objects under the broad umbrella of artifact, in which beauty has been achieved through the application of skills. Think of the average plastic spoon: a uniform white color, mass produced, and unremarkable in just about every way. While it serves a function—say, for example, to stir your hot chocolate—the person who designed it likely did so without any real dedication or commitment to making this utilitarian object beautiful. You have likely never lovingly gazed at a plastic spoon and remarked, “Wow! Now that’s a beautiful spoon!” This is in contrast to a silver spoon you might purchase at Tiffany & Co. While their spoon could just as well stir cream into your morning coffee, it was skillfully designed by a person who attempted to make it aesthetically pleasing; note the elegant bend of the handle, the gentle luster of the metal, the graceful slope of the bowl.

These terms are important to bear in mind when analyzing prehistoric art. While it is unlikely people from the Upper Paleolithic period cared to conceptualize what it meant to make art or to be an artist, it cannot be denied that the objects they created were made with skill, were often made as a way of imitating the world around them, and were made with a particular care to create something beautiful. They likely represent, for the Paleolithic peoples who created them, objects made with great competence and with a particular interest in aesthetics.

Caves and pockets

Two main types of Upper Paleolithic art have survived. The first we can classify as permanently located works found on the walls within caves. Mostly unknown prior to the final decades of the nineteenth century, many such sites have now been discovered throughout much of southern Europe and have provided historians and archaeologists new insights into humankind millennia prior to the creation of writing. The subjects of these works vary: we may observe a variety of geometric motifs, many types of flora and fauna, and the occasional human figure. They also fluctuate in size; ranging from several inches to large-scale compositions that span many feet in length.

The second category of Paleolithic art may be called portable since these works are generally of a small-scale—a logical size given the nomadic nature of Paleolithic peoples. Despite their often diminutive size, the creation of these portable objects signifies a remarkable allocation of time and effort. As such, these figurines were significant enough to take along during the nomadic wanderings of their Paleolithic creators. The Venus of Willendorf is a perfect example of this. Josef Szombathy, an Austro-Hungarian archaeologist, discovered this work in 1908 outside the small Austrian village of Willendorf. Although generally projected in art history classrooms to be several feet tall, this limestone figurine is petite in size. She measures just under 4½” high, and could fit comfortably in the palm of your hand. This small scale was very deliberate and allowed whoever carved (or, perhaps owned) this figurine to carry it during their nearly daily nomadic travels in search of food.

Naming and dating

Clearly, the Paleolithic sculptor who made this small figurine would never have named it the Venus of Willendorf. Venus was the name of the Roman goddess of love and ideal beauty. When discovered outside the Austrian village of Willendorf, scholars mistakenly assumed that this figure was likewise a goddess of love and beauty. There is absolutely no evidence though that the Venus of Willendorf shared a function similar to its classically inspired namesake. However incorrect the name may be, it has endured, and tells us more about those who found her than those who made her.

Dating too can be a problem, especially since Prehistoric art, by definition, has no written record. In fact, the definition of the word prehistoric is that written language did not yet exist, so the creator of the Venus of Willendorf could not have incised “Bob made this in the year 24,000 B.C.E.” on the back. In addition, stone artifacts present a special problem since we are interested in the date that the stone was carved, not the date of the material itself. Despite these hurdles, art historians and archaeologist attempt to establish dates for prehistoric finds through two processes. The first is called relative dating and the second involves an examination of the stratification of an object’s discovery.

Relative dating is an easily understood process that involves stylistically comparing an object whose date is uncertain to other objects whose dates have been firmly established. By correctly fitting the unknown object into this stylistic chronology, scholars can find a very general chronological date for an object. A simple example can illustrate this method. The first Chevrolet Corvette was sold during the 1953 model year, and this particular car has gone through numerous iterations up to its most recent version. If presented with pictures of the Corvette’s development from every five years to establish the stylistic development from its earliest model to the most recent (for example, images from the 1953, 1958, 1963, and all the way to the current model), you would have a general idea of the changes the car underwent over time. If then given a picture of a Corvette from an unknown year, you could, on the basis of stylistic analysis, generally place it within the visual chronology of this car with some accuracy. The Corvette is a convenient example, but the same exercise could be applied to iPods, Coca-Cola bottles, suits, or any other object that changes over time.

The second way scholars date the Venus of Willendorf is through an analysis of where it was found. Generally, the deeper an object is recovered from the earth, the longer that object has been buried. Imagine a penny jar that has had coins added to it for hundreds of years. It is a good bet that the coins at the bottom of that jar are the oldest whereas those at the top are the newest. The same applies to Paleolithic objects. Because of the depth at which these objects are found, we can infer that they are very old indeed.

What did it mean?

In the absence of writing, art historians rely on the objects themselves to learn about ancient peoples. The form of the Venus of Willendorf—that is, what it looks like—may very well inform what it originally meant. The most conspicuous elements of her anatomy are those that deal with the process of reproduction and child rearing. The artist took particular care to emphasize her breasts, which some scholars suggest indicates that she is able to nurse a child. The artist also brought deliberate attention to her pubic region. Traces of a pigment—red ochre—can still be seen on parts of the figurine.

In contrast, the sculptor placed scant attention on the non-reproductive parts of her body. This is particularly noticeable in the figure’s limbs, where there is little emphasis placed on musculature or anatomical accuracy. We may infer from the small size of her feet that she was not meant to be free standing, and was either meant to be carried or placed lying down. The artist carved the figure’s upper arms along her upper torso, and her lower arms are only barely visible resting upon the top of her breasts. As enigmatic as the lack of attention to her limbs is, the absence of attention to the face is even more striking. No eyes, nose, ears, or mouth remain visible. Instead, our attention is drawn to seven horizontal bands that wrap in concentric circles from the crown of her head. Some scholars have suggested her head is obscured by a knit cap pulled downward, others suggest that these forms may represent braided or beaded hair and that her face, perhaps once painted, is angled downward.

If the face was purposefully obscured, the Paleolithic sculptor may have created, not a portrait of a particular person, but rather a representation of the reproductive and child rearing aspects of a woman. In combination with the emphasis on the breasts and pubic area, it seems likely that the Venus of Willendorf had a function that related to fertility.

Without doubt, we can learn much more from the Venus of Willendorf than its diminutive size might at first suggest. We learn about relative dating and stratification. We learn that these nomadic people living almost 25,000 years ago cared about making objects beautiful. And we can learn that these Paleolithic people had an awareness of the importance of the women.

The Venus of Willendorf is only one example dozens of paleolithic figures we believe may have been associated with fertility. Nevertheless, it retains a place of prominence within the history of human art.

Hall of Bulls, Lascaux

We are as likely to communicate using easily interpretable pictures as we are text. Portable handheld devices enable us to tell others via social media what we are doing and thinking. Approximately 15,000 years ago, we also communicated in pictures—but with no written language.

The cave of Lascaux, France is one of almost 350 similar sites that are known to exist—most are isolated to a region of southern France and northern Spain. Both Neanderthals (named after the site in which their bones were first discovered—the Neander Valley in Germany) and Modern Humans (early Homo Sapiens Sapiens) coexisted in this region 30,000 years ago. Life was short and very difficult; resources were scarce and the climate was very cold.

Location, location, location!

Approximately 15,000 years later in the valley of Vèzére, in southwestern France, modern humans lived and witnessed the migratory patterns of a vast range of wildlife. They discovered a cave in a tall hill overlooking the valley. Inside, an unknown number of these people drew and painted images that, once discovered in 1940, have excited the imaginations of both researchers and the general public.

After struggling through small openings and narrow passages to access the larger rooms beyond, prehistoric people discovered that the cave wall surfaces functioned as the perfect, blank “canvas” upon which to draw and paint. White calcite, roofed by nonporous rock, provides a uniquely dry place to feature art. To paint, these early artists used charcoal and ochre (a kind of pigmented, earthen material, that is soft and can be mixed with liquids, and comes in a range of colors like brown, red, yellow, and white). We find images of horses, deer, bison, elk, a few lions, a rhinoceros, and a bear—almost as an encyclopedia of the area’s large prehistoric wildlife. Among these images are abstract marks—dots and lines in a variety of configurations. In one image, a humanoid figure plays a mysterious role.

How did they do it?

The animals are rendered in what has come to be called “twisted perspective,” in which their bodies are depicted in profile while we see the horns from a more frontal viewpoint. The images are sometimes entirely linear—line drawn to define the animal’s contour. In many other cases, the animals are described in solid and blended colors blown by mouth onto the wall. In other portions of the Lascaux cave, artists carved lines into the soft calcite surface. Some of these are infilled with color—others are not.

The cave spaces range widely in size and ease of access. The famous Hall of Bulls (below) is large enough to hold some fifty people. Other “rooms” and “halls” are extraordinarily narrow and tall.

Archaeologists have found hundreds of stone tools. They have also identified holes in some walls that may have supported tree-limb scaffolding that would have elevated an artist high enough to reach the upper surfaces. Fossilized pollen has been found; these grains were inadvertently brought into the cave by early visitors and are helping scientists understand the world outside.

Hall of Bulls

Given the large scale of many of the animal images, we can presume that the artists worked deliberately—carefully plotting out a particular form before completing outlines and adding color. Some researchers believe that “master” artists enlisted the help of assistants who mixed pigments and held animal fat lamps to illuminate the space. Alternatively, in the case of the “rooms” containing mostly engraved and overlapping forms, it seems that the pure process of drawing and repetitive re-drawing held serious (perhaps ritual) significance for the makers.

Why did they do it?

Many scholars have speculated about why prehistoric people painted and engraved the walls at Lascaux and other caves like it. Perhaps the most famous theory was put forth by a priest named Henri Breuil. Breuil spent considerable time in many of the caves, meticulously recording the images in drawings when the paintings were too challenging to photograph. Relying primarily on a field of study known as ethnography, Breuil believed that the images played a role in “hunting magic.” The theory suggests that the prehistoric people who used the cave may have believed that a way to overpower their prey involved creating images of it during rituals designed to ensure a successful hunt. This seems plausible when we remember that survival was entirely dependent on successful foraging and hunting, though it is also important to remember how little we actually know about these people.

Another theory suggests that the images communicate narratives (stories). While a number of the depictions can be seen to do this, one particular image in Lascaux more directly supports this theory. A bison, drawn in strong, black lines, bristles with energy, as the fur on the back of its neck stands up and the head is radically turned to face us (below).

A form drawn under the bison’s abdomen is interpreted as internal organs, spilling out from a wound. A more crudely drawn form positioned below and to the left of the bison may represent a humanoid figure with the head of a bird. Nearby, a thin line is topped with another bird and there is also an arrow with barbs. Further below and to the far left the partial outline of a rhinoceros can be identified.

Interpreters of this image tend to agree that some sort of interaction has taken place among these animals and the bird-headed human figure—in which the bison has sustained injury either from a weapon or from the horn of the rhinoceros. Why the person in the image has the rudimentary head of a bird, and why a bird form sits atop a stick very close to him is a mystery. Some suggest that the person is a shaman—a kind of priest or healer with powers involving the ability to communicate with spirits of other worlds. Regardless, this riveting image appears to depict action and reaction, although many aspects of it are difficult to piece together.

Preservation for future study

The Caves of Lascaux are the most famous of all of the known caves in the region. In fact, their popularity has permanently endangered them. From 1940 to 1963, the numbers of visitors and their impact on the delicately balanced environment of the cave—which supported the preservation of the cave images for so long—necessitated the cave’s closure to the public. A replica called Lascaux II was created about 200 yards away from the site. The original Lascaux cave is now a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. Lascaux will require constant vigilance and upkeep to preserve it for future generations.

Many mysteries continue to surround Lascaux, but there is one certainty. The very human need to communicate in the form of pictures—for whatever purpose—has persisted since our earliest beginnings.

The Neolithic revolution

A settled life

When people think of the Neolithic era, they often think of Stonehenge, the iconic image of this early time. Dating to approximately 3000 B.C.E. and set on Salisbury Plain in England, it is a structure larger and more complex than anything built before it in Europe. Stonehenge is an example of the cultural advances brought about by the Neolithic revolution—the most important development in human history. The way we live today, settled in homes, close to other people in towns and cities, protected by laws, eating food grown on farms, and with leisure time to learn, explore and invent is all a result of the Neolithic revolution, which occurred approximately 11,500-5,000 years ago. The revolution which led to our way of life was the development of the technology needed to plant and harvest crops and to domesticate animals.

Before the Neolithic revolution, it’s likely you would have lived with your extended family as a nomad, never staying anywhere for more than a few months, always living in temporary shelters, always searching for food and never owning anything you couldn’t easily pack in a pocket or a sack. The change to the Neolithic way of life was huge and led to many of the pleasures (lots of food, friends and a comfortable home) that we still enjoy today.

Editor’s Note: Each of the trilithons that form Stonehenge is comprised of three megaliths: two uprights and one balanced across the top. Post-and-lintel is a construction technique used in the Neolithic period and well beyond. It was used for both above-ground structures and underground burial chambers. Another building technique developed in the Neolithic period is the corbeled dome, as can be seen at the passage tomb at Newgrange.

Neolithic art

The massive changes in the way people lived also changed the types of art they made. Neolithic sculpture became bigger, in part, because people didn’t have to carry it around anymore; pottery became more widespread and was used to store food harvested from farms. Alcohol was first produced during this period and architecture, as well as its interior and exterior decoration, first appears. In short, people settled down and began to live in one place, year after year.

It seems very unlikely that Stonehenge could have been made by earlier, Paleolithic, nomads. It would have been a waste to invest so much time and energy building a monument in a place to which they might never return or might only return infrequently. After all, the effort to build it was extraordinary. Stonehenge is approximately 320 feet in circumference and the stones which compose the outer ring weigh as much as 50 tons; the small stones, weighing as much as 6 tons, were quarried from as far away as 450 miles. The use or meaning of Stonehenge is not clear, but the design, planning and execution could have only been carried out by a culture in which authority was unquestioned. Here is a culture that was able to rally hundreds of people to perform very hard work for extended periods of time. This is another characteristic of the Neolithic era.

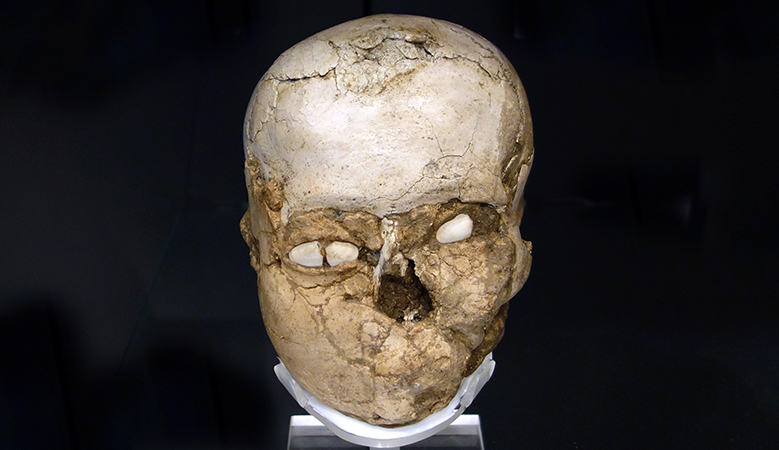

Plastered skulls

The Neolithic period is also important because it is when we first find good evidence for religious practice, a perpetual inspiration for the fine arts. Perhaps most fascinating are the plaster skulls found around the area of the Levant, at six sites, including Jericho. At this time in the Neolithic, c. 7000-6,000 B.C.E., people were often buried under the floors of homes, and in some cases their skulls were removed and covered with plaster in order to create very life-like faces, complete with shells inset for eyes and paint to imitate hair and mustaches.

The traditional interpretation of these the skulls has been that they offered a means of preserving and worshiping male ancestors. However, recent research has shown that among the sixty-one plastered skulls that have been found, there is a generous number that come from the bodies of women and children. Perhaps the skulls are not so much religious objects but rather powerful images made to aid in mourning lost loved ones.

Neolithic peoples didn’t have written language, so we may never know what their creators intended. (The earliest example of writing develops in Sumer in Mesopotamia in the late 4th millennium B.C.E. However, there are scholars that believe that earlier proto-writing developed during the Neolithic period).

Jericho

A natural oasis

The site of Jericho, just north of the Dead Sea and due west of the Jordan River, is one of the oldest continuously lived-in cities in the world. The reason for this may be found in its Arabic name, Ārīḥā, which means fragrant; Jericho is a natural oasis in the desert where countless fresh water springs can be found. This resource, which drew its first visitors between 10,000 and 9000 B.C.E., still has descendants that live there today.

Biblical reference

The site of Jericho is best known for its identity in the Bible and this has drawn pilgrims and explorers to it as early as the 4th century C.E.; serious archaeological exploration didn’t begin until the latter half of the 19th century. What continues to draw archaeologists to Jericho today is the hope of finding some evidence of the warrior Joshua, who led the Israelites to an unlikely victory against the Canaanites (“the walls of the city fell when Joshua and his men marched around them blowing horns” Joshua 6:1-27). Although unequivocal evidence of Joshua himself has yet to be found, what has been uncovered are some 12,000 years of human activity.

The most spectacular finds at Jericho, however, do not date to the time of Joshua, roughly the Bronze Age (3300-1200 B.C.E.), but rather to the earliest part of the Neolithic era, before even the technology to make pottery had been discovered.

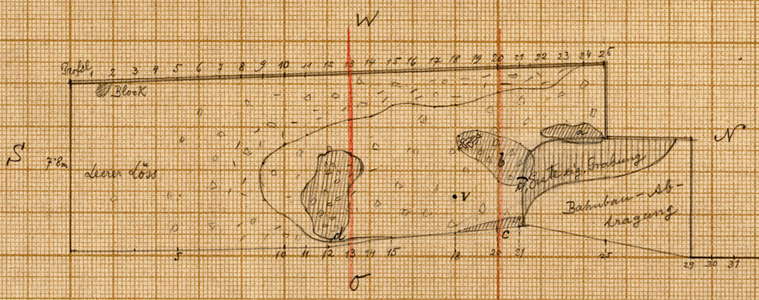

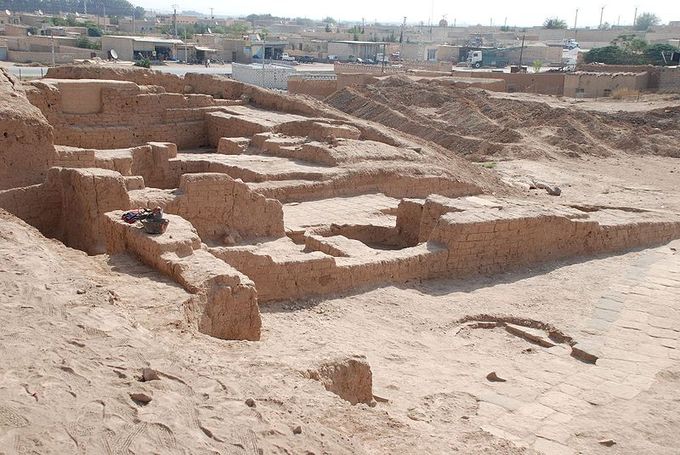

Old walls

The site of Jericho rises above the wide plain of the Jordan Valley, its height the result of layer upon layer of human habitation, a formation called a Tell. The earliest visitors to the site who left remains (stone tools) came in the Mesolithic period (around 9000 B.C.E.) but the first settlement at the site, around the Ein as-Sultan spring, dates to the early Neolithic era, and these people, who built homes, grew plants, and kept animals, were among the earliest to do such anywhere in the world. Specifically, in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A levels at Jericho (8500-7000 B.C.E.) archaeologists found remains of a very large settlement of circular homes made with mud brick and topped with domed roofs.

As the name of this era implies, these early people at Jericho had not yet figured out how to make pottery, but they made vessels out of stone, wove cloth and for tools were trading for a particularly useful kind of stone, obsidian, from as far away as Çiftlik, in eastern Turkey. The settlement grew quickly and, for reasons unknown, the inhabitants soon constructed a substantial stone wall and exterior ditch around their town, complete with a stone tower almost eight meters high, set against the inner side of the wall. Theories as to the function of this wall range from military defense to keeping out animal predators to even combating the natural rising of the level of the ground surrounding the settlement. However, regardless of its original use, here we have the first version of the walls Joshua so ably conquered some six thousand years later.

Plastered human skulls

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period is followed by the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7000-5200 BCE), which was different from its predecessor in important ways. Houses in this era were uniformly rectangular and constructed with a new kind of rectangular mud bricks which were decorated with herringbone thumb impressions, and always laid lengthwise in thick mud mortar. This mortar, like a plaster, was also used to create a smooth surface on the interior walls, extending down across the floors as well. In this period there is some strong evidence for cult or religious belief at Jericho. Archaeologists discovered one uniquely large building dating to the period with unique series of plastered interior pits and basins as well as domed adjoining structures and it is thought this was for ceremonial use.

Other possible evidence of cult practice was discovered in several homes of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic town, in the form of plastered human skulls which were molded over to resemble living heads. Shells were used for eyes and traces of paint revealed that skin and hair were also included in the representations. The largest group found together were nine examples, buried in the fill below the plastered floor of one house.

Jericho isn’t the only site at which plastered skulls have been found in Pre-Pottery Neolithic B levels; they have also been found at Tell Ramad, Beisamoun, Kfar Hahoresh, ‘Ain Ghazal and Nahal Hemar. Among the some sixty-two skulls discovered among these sites, we know that older and younger men as well as women and children are represented, which poses interesting questions as to their meaning. Were they focal points in ancestor worship, as was originally thought, or did they function as images by which deceased family members could be remembered? As we are without any written record of the belief system practiced in the Neolithic period in the area, we will never know.

Online Resources: The Jericho Skull

The British Museum, “The oldest portrait in the British Museum (probably) | Curator’s Corner S2 Ep 1” (https://youtu.be/bMZWsM687MY)

Also check out The Jericho Skull by The British Museum on Sketchfab

Phases of Neolithic Art

By Lumen Learning, Boundless Art History

Art in the Neolithic Near East owes its existence to developments in agriculture, architecture, and other areas…. Neolithic culture in the Near East is separated into three phases: Neolithic 1 (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A), Neolithic 2 (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B), and Neolithic 3 (Pottery Neolithic).

Neolithic 1 (PPNA)

The Neolithic 1 phase likely began with a temple in southeastern Turkey at Gobekli Tepe circa 10,000 BCE. The structure is as the oldest known human-made place of worship. It features seven stone circles covering 25 acres that contain limestone pillars carved with animals, insects, and birds, believed to serve as roof supports. The complexity of the temple and the effort involved in its construction imply it was built by long-term settlers. The major advances of the Neolithic 1 phase revolve around developments in farming practices, such as harvesting, seed selection, and the domestication of plants and animals.

At the oldest layer of Gobekli Tepe, T-shaped mud brick pillars are decorated with abstract , enigmatic pictograms and carved animal reliefs. The pictograms may represent commonly understood sacred symbols known from Neolithic cave paintings elsewhere. The reliefs depict mammals such as lions, bulls, boars, foxes, gazelles, and donkeys; snakes and other reptiles; arthropods, such as insects and arachnids; and birds, particularly vultures. The deceased were likely exposed for consumption by vultures and other carrion birds.

When the edifice was constructed, the surrounding country was likely forested and capable of sustaining this variety of wildlife, before millennia of settlement and cultivation led to the near-Dust Bowl conditions prevalent today.

Neolithic 2 (PPNB)

The Neolithic 2 began around 8800 BCE and is characterized by settlements built with rectangular mud-brick houses with single or multiple rooms, the greater use of domesticated animals, and advancements in tools. These developments in architecture point to settlement in permanent locations. While mud brick is perishable, the investment of time and effort in the construction of houses indicates the desire to remain in a single location for the long term. Burial findings and the preservation of skulls of the dead, often plastered with mud to create facial features, suggest an ancestor cult.

A settlement of 3,000 inhabitants was found in the outskirts of Amman, Jordan. Considered to be one of the largest prehistoric settlements in the Near East, ‘Ain Ghazal was continuously inhabited from approximately 7,250 – 5,000 BCE. This settlement produced what are believed to be the earliest large-scale human figures. Modeled from plaster, these consist of full statues and busts, some of which are two-headed. Great effort was put into modeling the heads, with wide-open eyes and bitumen-outlined irises. The statues represent men, women, and children. Women are recognizable by features resembling breasts and slightly enlarged bellies, but neither male nor female sexual characteristics are emphasized, and none of the statues have genitals. Only the faces have detail.

Although they were produced to be free-standing, they were likely intended to be viewed only from the front, hence their disproportionate flatness. The manufacture of the statues would not have permitted them to last long. Since they were buried in pristine condition, they may have been produced for the purpose of intentional burial and never been displayed.

Neolithic 3 (PN)

Beginning around 6400 BCE, this period is characterized by the emergence of distinctive cultures throughout the Fertile Crescent , such as the Halafian (Turkey, Syria, Northern Mesopotamia) and Ubaid (Southern Mesopotamia).

Pottery was first produced and used in this era, a direct effect of agriculture and the permanent settlements that arose as a result. No longer nomadic , individuals used ceramic vessels to store the food they grew or raised and water collected from local sources. Additionally, the need arose for plates, cups, and additional objects used in the consumption of food and beverages.

Halafian Period

Tell Halaf is an archaeological site in northeastern Syria near the Turkish border, that flourished from about 6100 to 5400 BCE. It was the first site of Neolithic culture, subsequently dubbed Halafian culture, characterized by glazed pottery painted with geometric and animal designs.

The best known, most characteristic pottery of Tell Halaf, called Halaf ware, was produced by specialist potters. It was sometimes painted with one or two colors (the latter called polychrome) with geometric and animal motifs . Other types of Halaf pottery include unpainted cookware and ware with burnished surfaces.

There are many theories about the development of this distinctive pottery style . The polychromatic painted Halaf pottery has been proposed to be a “trade pottery”—pottery produced for export—however, the predominance of locally produced painted pottery in all areas of Halaf sites calls that theory into question. That said, Halaf pottery has been found in other parts of northern Mesopotamia and at many sites in Anatolia (Turkey) suggesting that it was widely used in the region.

Halafian pottery

These pieces were produced by specialist potters. Some were painted with geometric and animal motifs.

In addition to ceramics, the Halafian culture produced female figurines of partially baked clay and stone. Because of the prominence of their breasts and abdomens and subordination of their facial features, they are likely fertility figures. As the bands on the figure below suggest, these figurines were painted to some extent.

Ubaid Period

The Ubaid culture flourished from about 6500 to 3800 BCE in Mesopotamia and is characterized by large village settlements that employed multi-room rectangular mud-brick houses. The appearance of the first temples in Mesopotamia, as well as greenish pottery decorated with geometric designs in brown or black paint, are important developments of this period. Tell-al-Ubaid is a low, relatively small mound site that extends about two meters above ground level. The lower level was a site where large amounts of Ubaid pottery, kilns, and a cemetery were discovered.

Çatalhöyük

Çatalhöyük or Çatal Höyük (pronounced “cha-tal hay OOK”) is not the oldest site of the Neolithic era or the largest, but it is extremely important to the beginning of art. Located near the modern city of Konya in south central Turkey, it was inhabited 9000 years ago by up to 8000 people who lived together in a large town. Çatalhöyük, across its history, witnesses the transition from exclusively hunting and gathering subsistence to increasing skill in plant and animal domestication. We might see Çatalhöyük as a site whose history is about one of man’s most important transformations: from nomad to settler. It is also a site at which we see art, both painting and sculpture, appear to play a newly important role in the lives of settled people.

Çatalhöyük had no streets or foot paths; the houses were built right up against each other and the people who lived in them traveled over the town’s rooftops and entered their homes through holes in the roofs, climbing down a ladder. Communal ovens were built above the homes of Çatalhöyük and we can assume group activities were performed in this elevated space as well.

Like at Jericho, the deceased were placed under the floors or platforms in houses and sometimes the skulls were removed and plastered to resemble live faces. The burials at Çatalhöyük show no significant variations, either based on wealth or gender; the only bodies which were treated differently, decorated with beads and covered with ochre, were those of children. The excavator of

Çatalhöyük believes that this special concern for youths at the site may be a reflection of the society becoming more sedentary and required larger numbers of children because of increased labor, exchange and inheritance needs.

Art is everywhere among the remains of Çatalhöyük, geometric designs as well as representations of animals and people. Repeated lozenges and zigzags dance across smooth plaster walls, people are sculpted in clay, pairs of leopards are formed in relief facing one another at the sides of rooms, hunting parties are painted baiting a wild bull. The volume and variety of art at Çatalhöyük is immense and must be understood as a vital, functional part of the everyday lives of its ancient inhabitants.

Many figurines have been found at the site, the most famous of which illustrates a large woman seated on or between two large felines. The figurines, which illustrate both humans and animals, are made from a variety of materials but the largest proportion are quite small and made of barely fired clay. These casual figurines are found most frequently in garbage pits, but also in oven walls, house walls, floors and left in abandoned structures. The figurines often show evidence of having been poked, scratched or broken, and it is generally believed that they functioned as wish tokens or to ward off bad spirits.

Nearly every house excavated at Çatalhöyük was found to contain decorations on its walls and platforms, most often in the main room of the house. Moreover, this work was constantly being renewed; the plaster of the main room of a house seems to have been redone as frequently as every month or season. Both geometric and figural images were popular in two-dimensional wall

painting and the excavator of the site believes that geometric wall painting was particularly associated with adjacent buried youths. Figural paintings show the animal world alone, such as, for instance, two cranes facing each other standing behind a fox, or in interaction with people, such as a vulture pecking at a human corpse or hunting scenes. Wall reliefs are found at Çatalhöyük with some frequency, most often representing animals, such as pairs of animals facing each other and human-like creatures. These latter reliefs, alternatively thought to be bears, goddesses or regular humans, are always represented splayed, with their heads, hands and feet removed, presumably at the time the house was abandoned.

The most remarkable art found at Çatalhöyük, however, are the installations of animal remains and among these the most striking are the bull bucrania. In many houses the main room was decorated with several plastered skulls of bulls set into the walls (most common on East or West walls) or platforms, the pointed horns thrust out into the communal space. Often the bucrania would be painted ochre red. In addition to these, the remains of other animals’ skulls, teeth, beaks, tusks or horns were set into the walls and platforms, plastered and painted. It would appear that the ancient residents of Çatalhöyük were only interested in taking the pointy parts of the animals back to their homes!

How can we possibly understand this practice of interior decoration with the remains of animals? A clue might be in the types of creatures found and represented. Most of the animals represented in the art of Çatalhöyük were not domesticated; wild animals dominate the art at the site. Interestingly, examination of bone refuse shows that the majority of the meat which was consumed was of wild animals, especially bulls. The excavator believes this selection in art and cuisine had to do with the contemporary era of increased domestication of animals and what is being celebrated are the animals which are part of the memory of the recent cultural past, when hunting was much more important for survival.

Articles in this chapter:

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Paleolithic art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, June 8, 2018

- Dr. Bryan Zygmont, “Venus of Willendorf,” in Smarthistory, November 21, 2015

- Mary Beth Looney, “Hall of Bulls, Lascaux,” in Smarthistory, November 19, 2015

- Dr. Senta German, “The Neolithic revolution,” in Smarthistory, June 8, 2018

- Dr. Senta German, “Jericho,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015

- Lumen Learning, “The Neolithic Period“

- Dr. Senta German, “Çatalhöyük,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015

the material(s) from which a work of art is made

a style of representation that seeks to recreate the visible world or nature

a style of representation that veers from naturalism, often flattening recognizable natural forms into shapes which may or may not be recognizably figurative

a sculpture that can be observed from all sides, unlike a relief sculpture that doesn't fully detach from its background

unlike sculptures in the round, reliefs don't detach entirely from their background. A sculpture may be in high relief, with greater projection from the background, or in low (bas) relief, where there is little projection. In ancient Egypt, we see sunken relief, where instead of projecting from the surface, the figures are delineated by carved-in contour lines.

Upper Paleolithic refers to the period between approximately 40,000 and 10,000 years ago.

"Upper" is the most recent of three sub-divisions of the Paleolithic period (Lower, Middle and Upper). The word itself is made of two parts. "Paleo" which means old and "lithic" which means stone. Stone Age is a reference to the chronology of material technology of a given time. The Stone Age comes before the Bronze Age for example.

Paleolithic is the oldest of three stone-age periods (Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic). Thus "Upper Paleolithic" refers to the most recent period of the old stone age.

a material, often in powdered form, that is applied directly to a surface or mixed with liquid, such as oil or water, to create paint

a style of representation in which figures are depicted with combination frontal and profile views. Also known as composite view.

a grouping of three massive stones, from the Latin tri- (three) + Greek: litho- (stone)

a massive rock, from the Greek mega (big) and lith (stone)

a simple architectural technique of enclosing space using upright supports (posts) topped by a crosspiece (lintel)

a naturally-occurring tar used as an adhesive and decorative material

consisting of more than one colors, from the Greek poly (many) + chroma (color)