10

Lumen Learning; Dr. Jaclyn Neel; Dr. Jessica Leay Ambler; Dr. Jeffrey Becker; Julia Fischer; and British Museum

In this chapter

Introduction

Republic

Early Empire

High Empire

Late Empire

The Romans

Foundation Myths

The Romans relied on two sets of myths to explain their origins: the first story tells the tale of Romulus and Remus, while the second tells the story of Aeneas and the Trojans, who survived the sack of Troy by the Greeks. Oddly, both stories relate the founding of Rome and the origins of its people to brutal murders.

Romulus killed his twin brother, Remus, in a fit of rage, and Aeneas slaughtered his rival Turnus in combat. Roman historians used these mythical episodes as the reason for Rome’s own bloody history and periods of civil war. While foundation myths are the most common vehicle through which we learn about the origins of Rome and the Roman people, the actual history is often overlooked.

The Historical Record

Archaeological evidence shows that the area that eventually became Rome has been inhabited continuously for the past 14,000 years. The historical record provides evidence of habitation on and fortification of the Palatine Hill during the eighth century BCE, which supports the date of April 21, 753 BCE, as the date that ancient historians applied to the founding of Rome in association with a festival to Pales, the goddess of shepherds. Given the importance of agriculture to pre-Roman tribes, as well as most ancestors of civilization , it is logical that the Romans would link the celebration of their founding as a city to an agrarian goddess.

Romulus, whose name is believed to be the namesake of Rome, is credited for Rome’s founding. He is also credited with establishing the period of monarchical rule. Six kings ruled after him until 509 BCE, when the people rebelled against the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, and established the Republic. Throughout its history, the people—including plebeians, patricians, and senators—were wary of giving one person too much power and feared the tyranny of a king.

Pre-Roman Tribes

The villages that would eventually merge to become Rome were descended from the Italic tribes. The Italic tribes spread throughout the present-day countries of Italy and Sicily. Archaeological evidence and ancient writings provide very little information on how—or whether—pre-Roman tribes across the Italian peninsula interacted.

What is known is that they all belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family, which gave rise to the Romance (Latin-derived) and Germanic languages. What follows is a brief history of two of the eight main tribes that contributed to the founding of Rome: the Latins and the Sabines. Information about a third culture, the Etruscans, is found in Chapter 7.

The Latins

The Latins inhabited the Alban Hills since the second millennium BCE. According to archaeological remains, the Latins were primarily farmers and pastoralists . Approximately at the end of the first millennium BCE, they moved into the valleys and along the Tiber River, which provided better land for agriculture.

Although divided from an early stage into communities that mutated into several independent, and often warring, city-states , the Latins and their neighbors maintained close culturo-religious relations until they were definitively united politically under Rome. These included common festivals and religious sanctuaries.

The Latins appear to have become culturally differentiated from the surrounding Italic tribes from about 1000 BCE onward. From this time, the Latins’ material culture shares more in common with the Iron Age Villanovan culture found in Etruria and the Po valley than with their former Osco-Umbrian neighbors.

The Latins thus shared a similar material culture as the Etruscans. However, archaeologists have discerned among the Latins a variant of Villanovan, dubbed the Latial culture.

The most distinctive feature of Latial culture were cinerary urns in the shape of huts . They represent the typical, single-room abodes of the area’s peasants, which were made from simple, readily available materials: wattle-and-daub walls and straw roofs supported by wooden posts. The huts remained the main form of Latin housing until the mid-seventh century BCE.

The Sabines

The Sabines originally inhabited the Apennines and eventually relocated to Latium before the founding of Rome. The Sabines divided into two populations just after the founding of Rome. The division, however it came about, is not legendary.

The population closer to Rome transplanted itself to the new city and united with the pre-existing citizenry to start a new heritage that descended from the Sabines but was also Latinized. The second population remained a mountain tribal state, finally fighting against Rome for its independence along with all the other Italic tribes. After losing, it became assimilated into the Roman Republic.

There is little record of the Sabine language. However, there are some glosses by ancient commentators, and one or two inscriptions have been tentatively identified as Sabine. There are also personal names in use on Latin inscriptions from the Sabine territories, but these are given in Latin form. The existing scholarship classifies Sabine as a member of the Umbrian group of Italic languages and identifies approximately 100 words that are either likely Sabine or that possess Sabine origin.

The Seven Hills

Before Rome was founded as a city, its people existed in separate settlements atop its famous Seven Hills:

- The Aventine Hill

- The Caelian Hill

- The Capitoline Hill

- The Esquiline Hill

- The Palatine Hill

- The Quirinal Hill

- The Viminal Hill

Over time, each tribe either united with or was absorbed into the Roman culture.

The Quirinal Hill

Recent studies suggest that the Quirinal Hill was very important to the ancient Romans and their immediate ancestors. It was here that the Sabines originally resided. Its three peaks were united with the three peaks of the Esquiline, as well as villages on the Caelian Hill and Suburra.

Tombs from the eighth to the seventh century BCE that confirm a likely presence of a Sabine settlement area were discovered on the Quirinal Hill. Some authors consider it possible that the cult of the Capitoline Triad (Jove, Minerva, Juno) could have been celebrated here well before it became associated with the Capitoline Hill. The sanctuary of Flora, an Osco-Sabine goddess, was also at this location. Titus Livius (better known as Livy) writes that the Quirinal Hill, along with the Viminal Hill, became part of Rome in the sixth century BCE.

The Palatine Hill

According to Livy, the Palatine Hill, located at the center of the ancient city, became the home of the original Romans after the Sabines and the Albans moved into the Roman lowlands. Due to its historical and legendary significance, the Palatine Hill became the home of many Roman elites during the Republic and emperors during the Empire.

It was also the site of a temple to Apollo built by Emperor Augustus and the pastoral (and possibly pre-Roman) festival of Lupercalia, which was observed on February 13 through 15 to avert evil spirits, purify the city, and release health and fertility.

Festivals for the Septimontium (meaning of the Seven Hills) on December 11 were previously considered to be related to the foundation of Rome. However, because April 21 is the agreed-upon date of the city’s founding, it has recently been argued that Septimontium celebrated the first federations among the Seven Hills. A similar federation was celebrated by the Latins at Cave or Monte Cavo.

Social Structure

Life in ancient Rome centered around the capital city with its fora, temples, theaters, baths, gymnasia, brothels, and other forms of culture and entertainment. Private housing ranged from elegant urban palaces and country villas for the social elites to crowded insulae (apartment buildings) for the majority of the population.

The large urban population required an endless supply of food, which was a complex logistical task. Area farms provided produce, while animal-derived products were considered luxuries. The aqueducts brought water to urban centers, and wine and oil were imported from Hispania (Spain and Portugal), Gaul (France and Belgium), and Africa.

Highly efficient technology allowed for frequent commerce among the provinces. While the population within the city of Rome might have exceeded one million, most Romans lived in rural areas, each with an average population of 10,000 inhabitants.

Roman society consisted of patricians , equites (equestrians, or knights), plebeians , and slaves. All categories except slaves enjoyed the status of citizenship.

In the beginning of the Roman republic, plebeians could neither intermarry with patricians or hold elite status, but this changed by the Late Republic, when the plebeian-born Octavian rose to elite status and eventually became the first emperor. Over time, legislation was passed to protect the lives and health of slaves.

Although many prostitutes were slaves, for instance, the bill of sale for some slaves stipulated that they could not be used for commercial prostitution. Slaves could become freedmen—and thus citizens—if their owners freed them or if they purchased their freedom by paying their owners. Free-born women were considered citizens, although they could neither vote nor hold political office.

Pater Familias

Within the household, the pater familias was the seat of authority, possessing power over his wife, the other women who bore his sons, his children, his nephews, his slaves, and the freedmen to whom he granted freedom. His power extended to the point of disposing of his dependents and their good, as well as having them put to death if he chose.

In private and public life, Romans were guided by the mos maiorum, an unwritten code from which the ancient Romans derived their social norms that affected all aspects of life in ancient Rome.

Government

Over the course of its history, Rome existed as a kingdom (hereditary monarchy), a republic (in which leaders were elected), and an empire (a kingdom encompassing a wider swath of territory). From the establishment of the city in 753 BCE to the fall of the empire in 476 CE, the Senate was a fixture in the political culture of Rome, although the power it exerted did not remain constant.

During the days of the kingdom, it was little more than an advisory council to the king. Over the course of the Republic, the Senate reached the height of its power, with old-age becoming a symbol of prestige, as only elders could serve as senators. However the late Republic witnessed the beginning of its decline. After Augustus ended the Republic to form the Empire, the Senate lost much of its power, and with the reforms of Diocletian in the third century CE, it became irrelevant.

As Rome grew as a global power, its government was subdivided into colonial and municipal levels. Colonies were modeled closely on the Roman constitution, with roles being defined for magistrates, council, and assemblies. Colonists enjoyed full Roman citizenship and were thus extensions of Rome itself.

The second most prestigious class of cities was the municipium (a town or city). Municipia were originally communities of non-citizens among Rome’s Italic allies. Later, Roman citizenship was awarded to all Italy, with the result that a municipium was effectively now a community of citizens. The category was also used in the provinces to describe cities that used Roman law but were not colonies.

Religion

The Roman people considered themselves to be very religious. Religious beliefs and practices helped establish stability and social order among the Romans during the reign of Romulus and the period of the legendary kings. Some of the highest religious offices, such as the Pontifex Maximus , the head of the state’s religion—which eventually became one of the titles of the emperor—were sought-after political positions.

Women who became Vestal Virgins served the goddess of the hearth, Vesta, and received a high degree of autonomy within the state, including rights that other women would never receive.

The Roman pantheon corresponded to the Etruscan and Greek deities. Jupiter was considered the most powerful and important of all the Gods.

In nearly every Roman city, a central temple known as the Capitolia that was dedicated to the supreme triad of deities: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva (Zeus, Hera, and Athena). Small household gods, known as Lares, were also popular.

Each family claimed their own set of personal gods and laraium, or shines to the Lares, are found not only in houses but also at street corners, on roads, or for a city neighborhood.

Roman religious practice often centered around prayers, vows, oaths, and sacrifice . Many Romans looked to the gods for protection and would complete a promise sacrifice or offering as thanks when their wishes were fulfilled. The Romans were not exclusive in their religious practices and easily participated in numerous rituals for different gods. Furthermore, the Romans readily absorbed foreign gods and cults into their pantheon.

Capitoline Triad: Juno, Jupiter, and Minerva made up the Capitoline Triad. They often shared a temple, known as the Capitolia, in the center of a Roman city. This photo is taken in the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, Palestrina, Italy.With the rise of imperial rule, the emperors were considered gods, and temples were built to many emperors upon their death. Their family members could also be deified, and the household gods of the emperor’s family were also incorporated into Roman worship.

Capitoline She-wolf

Rome’s eternal symbol?

If one could choose any animal to become one’s mother, how many people would choose a wolf? Wolves are not known to be the gentlest of animals, and in the ancient world, when many people made their living as shepherds, wolves could pose a significant threat. But for reasons we do not understand, the Romans chose a wolf as their symbol. According to Roman mythology, the city’s twin founders Romulus and Remus were abandoned on the banks of the Tiber River when they were infants. A she-wolf saved their lives by letting them suckle. The image of this miracle quickly became a symbol of the city of Rome, appearing on coinage in the third century B.C.E. and continuing to appear on public monuments from trash-cans to lampposts in the city even to this day. But the most famous image of the she-wolf and twins may not be ancient at all—at least not entirely.

Description

The Capitoline She-wolf (Italian: Lupa capitolina) takes its name from its location—the statue is housed in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The She-wolf statue is a fully worked bronze composition that is intended for 360 degree viewing. In other words the viewer can get an equally good view from all directions: there is no “correct” point of view. The She-wolf is depicted standing in a stationary pose. The body is out of proportion, because its neck is much too long for its face and flanks. The incised details of the neck show thick, s-curled fur which ends with unnatural beads around the face and behind the forelegs. The wolf’s body is leaner in front than in the rear: its ribs are visible, as are the muscles of its forelegs, while in the back the musculature is less detailed, suggesting less tone. Its head curves in towards its tail; the ears curve back. The children themselves have a more dynamic posture: one sits with his feet splaying to either side, while the other kneels beside him. Both face upwards. They, too, are lean, with no trace of baby fat.

Hollow-cast bronze: a refresher

The She-wolf is a hollow-cast bronze statue that is just under life-sized. Hollow casting is one of the many ways that metal sculptures were made in the ancient world. It was the typical method for large-scale bronze statues.

In antiquity, hollow casting (also known as “lost-wax casting”) could be a lengthy procedure. A large sculpture was made in many smaller pieces, and these were joined as the last step of the process. A sculptor first made a model of the statue in a less-valuable medium, such as clay. He then coated the model with a second model, which was made in multiple pieces so it could be removed. Once removed, the second model was coated in wax and another layer of clay. The second and third models were then attached to each other and fired, leaving a hollow space as the wax melted. Molten metal was poured in to replace the wax, and the molds were (at last) removed only when the metal had cooled and set. In the case of large statues, the pieces were soldered together and polished as a final step.

But although the She-wolf is hollow-cast, it is not made of multiple pieces. This has raised significant questions about whether the wolf is ancient at all.

Questions of chronology

While it was known for some time that the twins are Renaissance additions to the sculpture, it was not until 2006 that the chronology of the She-wolf itself was challenged. Long believed to date to fifth century B.C.E. Etruria (Etruscan culture), the She-wolf’s date is now debated. If ancient, the original sculpture probably would not have depicted Rome’s she-wolf. We do know that Romans engaged in regional trade that led them to acquire art objects from surrounding areas, including Etruria (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.45). But in the fifth century B.C.E., Rome was still a fairly small city, and possibly had not yet begun using the she-wolf and twins as its symbol. Other Etruscan artifacts (like the Lupa of Fiesole below) have a lone wolf as part of a hunt or ritual, and it is more likely that a fifth century B.C.E. Etruscan object would relate to Etruscan culture, rather than Roman culture.

But new laboratory analysis suggests that the She-wolf is not ancient and was made in the Middle Ages, specifically the twelfth century C.E. Questions about the authenticity of the She-wolf were first raised when the statue was restored in the late 1990s. At that time, conservators realized that the casting technique used to make it is not the same as the hollow casting technique used on other large-scale bronze sculptures. Instead of using multiple molds, as described above, the She-wolf is made as a single piece. Proponents of this view argue that the wolf is more similar stylistically to medieval bronzes. Proponents of the Etruscan date claim that the few surviving Etruscan large-scale bronze statues are stylistically similar to the She-wolf.

The claim that the She-wolf is medieval has generated a lot of controversy in Italy and among scholars of ancient Rome. Several respected researchers have publicly disputed the new findings and maintain the She-wolf’s Etruscan provenance. Physical and chemical testing on the bronze has been inconclusive about the date. The Capitoline Museums admit both possibilities in the object’s description.

Conclusion

Although the debate continues with regard to the date of the Capitoline She-wolf, either interpretation offers interesting points for analysis. The only definitive testimony suggests that materials used in casting the wolf came from both Sardinia and Rome. If the work is from the fifth century B.C.E., we can use that evidence to analyze trade patterns in Italy. Remembering that the wolf was originally cast without the twins—no matter what date we assign to the wolf sculpture—we can try to imagine the original significance of the statue.

On the other hand, if the wolf is medieval, what was its original function? We should not think that a medieval wolf is any less valuable just because it is more recent in its date of manufacture. In fact, a pastiche Capitoline She-wolf might be an even better symbol of Rome: a Renaissance addition to a medieval statue that recreates the ancient symbol of the eternal city.

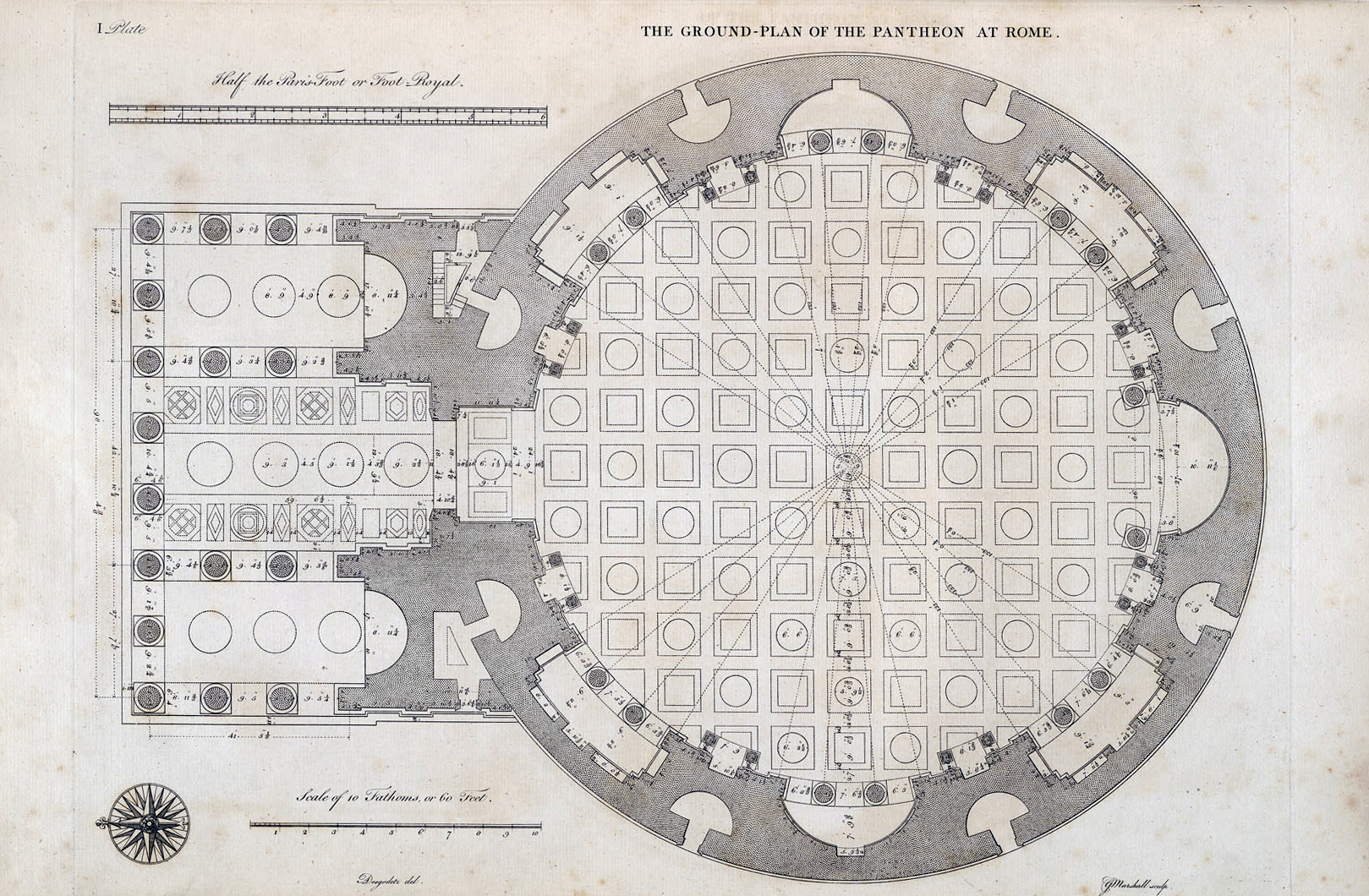

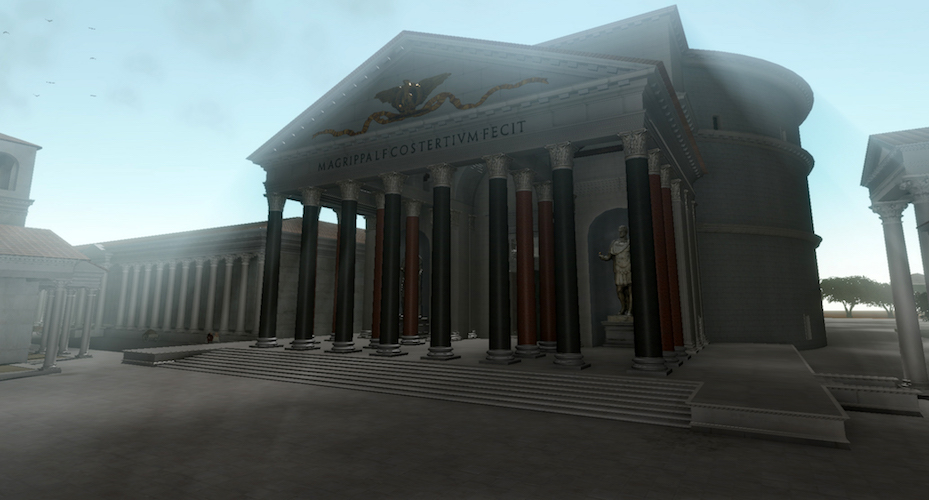

An introduction to ancient Roman architecture

Roman architecture was unlike anything that had come before. The Persians, Egyptians, Greeks and Etruscans all had monumental architecture. The grandeur of their buildings, though, was largely external. Buildings were designed to be impressive when viewed from outside because their architects all had to rely on building in a post-and-lintel system, which means that they used two upright posts, like columns, with a horizontal block, known as a lintel, laid flat across the top. A good example is this ancient Greek Temple in Paestum, Italy.

Since lintels are heavy, the interior spaces of buildings could only be limited in size. Much of the interior space had to be devoted to supporting heavy loads.

Roman architecture differed fundamentally from this tradition because of the discovery, experimentation and exploitation of concrete, arches and vaulting (a good example of this is the Pantheon, c. 125 C.E.). Thanks to these innovations, from the first century C.E. Romans were able to create interior spaces that had previously been unheard of. Romans became increasingly concerned with shaping interior space rather than filling it with structural supports. As a result, the inside of Roman buildings were as impressive as their exteriors.

Materials, methods and innovations

Long before concrete made its appearance on the building scene in Rome, the Romans utilized a volcanic stone native to Italy called tufa to construct their buildings. Although tufa never went out of use, travertine began to be utilized in the late 2nd century B.C.E. because it was more durable. Also, its off-white color made it an acceptable substitute for marble.

Marble was slow to catch on in Rome during the Republican period since it was seen as an extravagance, but after the reign of Augustus (31 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), marble became quite fashionable. Augustus had famously claimed in his funerary inscription, known as the Res Gestae, that he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble” referring to his ambitious building campaigns.

Roman concrete (opus caementicium), was developed early in the 2nd c. BCE. The use of mortar as a bonding agent in ashlar masonry wasn’t new in the ancient world; mortar was a combination of sand, lime and water in proper proportions. The major contribution the Romans made to the mortar recipe was the introduction of volcanic Italian sand (also known as “pozzolana”). The Roman builders who used pozzolana rather than ordinary sand noticed that their mortar was incredibly strong and durable. It also had the ability to set underwater. Brick and tile were commonly plastered over the concrete since it was not considered very pretty on its own, but concrete’s structural possibilities were far more important. The invention of opus caementicium initiated the Roman architectural revolution, allowing for builders to be much more creative with their designs. Since concrete takes the shape of the mold or frame it is poured into, buildings began to take on ever more fluid and creative shapes.

The Romans also exploited the opportunities afforded to architects by the innovation of the true arch (as opposed to a corbeled arch where stones are laid so that they move slightly in toward the center as they move higher). A true arch is composed of wedge-shaped blocks (typically of a durable stone), called voussoirs, with a keystone in the center holding them into place. In a true arch, weight is transferred from one voussoir down to the next, from the top of the arch to ground level, creating a sturdy building tool. True arches can span greater distances than a simple post-and-lintel. The use of concrete, combined with the employment of true arches allowed for vaults and domes to be built, creating expansive and breathtaking interior spaces.

Roman architects

We don’t know much about Roman architects. Few individual architects are known to us because the dedicatory inscriptions, which appear on finished buildings, usually commemorated the person who commissioned and paid for the structure. We do know that architects came from all walks of life, from freedmen all the way up to the Emperor Hadrian, and they were responsible for all aspects of building on a project. The architect would design the building and act as engineer; he would serve as contractor and supervisor and would attempt to keep the project within budget.

Building types

Roman cities were typically focused on the forum (a large open plaza, surrounded by important buildings), which was the civic, religious and economic heart of the city. It was in the city’s forum that major temples (such as a Capitoline temple, dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) were located, as well as other important shrines. Also useful in the forum plan were the basilica (a law court), and other official meeting places for the town council, such as a curia building. Quite often the city’s meat, fish and vegetable markets sprang up around the bustling forum. Surrounding the forum, lining the city’s streets, framing gateways, and marking crossings stood the connective architecture of the city: the porticoes, colonnades, arches and fountains that beautified a Roman city and welcomed weary travelers to town. Pompeii, Italy is an excellent example of a city with a well preserved forum.

Romans had a wide range of housing. The wealthy could own a house (domus) in the city as well as a country farmhouse (villa), while the less fortunate lived in multi-story apartment buildings called insulae. The House of Diana in Ostia, Rome’s port city, from the late 2nd c. C.E. is a great example of an insula. Even in death, the Romans found the need to construct grand buildings to commemorate and house their remains, like Eurysaces the Baker, whose elaborate tomb still stands near the Porta Maggiore in Rome.

The Romans built aqueducts throughout their domain and introduced water into the cities they built and occupied, increasing sanitary conditions. A ready supply of water also allowed bath houses to become standard features of Roman cities, from Timgad, Algeria to Bath, England. A healthy Roman lifestyle also included trips to the gymnasium. Quite often, in the Imperial period, grand gymnasium-bath complexes were built and funded by the state, such as the Baths of Caracalla which included running tracks, gardens and libraries.

Entertainment varied greatly to suit all tastes in Rome, necessitating the erection of many types of structures. There were Greek style theaters for plays as well as smaller, more intimate odeon buildings, like the one in Pompeii, which were specifically designed for musical performances. The Romans also built amphitheaters—elliptical, enclosed spaces such as the Colloseum—which were used for gladiatorial combats or battles between men and animals. The Romans also built a circus in many of their cities. The circuses, such as the one in Lepcis Magna, Libya, were venues for residents to watch chariot racing.

The Romans continued to perfect their bridge building and road laying skills as well, allowing them to cross rivers and gullies and traverse great distances in order to expand their empire and better supervise it. From the bridge in Alcántara, Spain to the paved roads in Petra, Jordan, the Romans moved messages, money and troops efficiently.

Republican period

Republican Roman architecture was influenced by the Etruscans who were the early kings of Rome; the Etruscans were in turn influenced by Greek architecture. The Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, begun in the late 6th century B.C.E., bears all the hallmarks of Etruscan architecture. The temple was erected from local tufa on a high podium and what is most characteristic is its frontality. The porch is very deep and the visitor is meant to approach from only one access point, rather than walk all the way around, as was common in Greek temples. Also, the presence of three cellas, or cult rooms, was also unique. The Temple of Jupiter would remain influential in temple design for much of the Republican period.

Drawing on such deep and rich traditions didn’t mean that Roman architects were unwilling to try new things. In the late Republican period, architects began to experiment with concrete, testing its capability to see how the material might allow them to build on a grand scale.

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in modern day Palestrina is comprised of two complexes, an upper and a lower one. The upper complex is built into a hillside and terraced, much like a Hellenistic sanctuary, with ramps and stairs leading from the terraces to the small theater and tholos temple at the pinnacle. The entire compound is intricately woven together to manipulate the visitor’s experience of sight, daylight and the approach to the sanctuary itself. No longer dependent on post-and-lintel architecture, the builders utilized concrete to make a vast system of covered ramps, large terraces, shops and barrel vaults.

Imperial period

The Emperor Nero began building his infamous Domus Aurea, or Golden House, after a great fire swept through Rome in 64 C.E. and destroyed much of the downtown area. The destruction allowed Nero to take over valuable real estate for his own building project; a vast new villa. Although the choice was not in the public interest, Nero’s desire to live in grand fashion did spur on the architectural revolution in Rome. The architects, Severus and Celer, are known (thanks to the Roman historian Tacitus), and they built a grand palace, complete with courtyards, dining rooms, colonnades and fountains. They also used concrete extensively, including barrel vaults and domes throughout the complex. What makes the Golden House unique in Roman architecture is that Severus and Celer were using concrete in new and exciting ways; rather than utilizing the material for just its structural purposes, the architects began to experiment with concrete in aesthetic modes, for instance, to make expansive domed spaces.

Nero may have started a new trend for bigger and better concrete architecture, but Roman architects, and the emperors who supported them, took that trend and pushed it to its greatest potential. Vespasian’s Colosseum, the Markets of Trajan, the Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius are just a few of the most impressive structures to come out of the architectural revolution in Rome. Roman architecture was not entirely comprised of concrete, however. Some buildings, which were made from marble, hearkened back to the sober, Classical beauty of Greek architecture, like the Forum of Trajan. Concrete structures and marble buildings stood side by side in Rome, demonstrating that the Romans appreciated the architectural history of the Mediterranean just as much as they did their own innovation. Ultimately, Roman architecture is overwhelmingly a success story of experimentation and the desire to achieve something new.

Temple of Portunus, Rome

The Temple of Portunus is a well preserved late second or early first century B.C.E. rectangular temple in Rome, Italy. Its dedication to the God Portunus—a divinity associated with livestock, keys, and harbors—is fitting given the building’s topographical position near the ancient river harbor of the city of Rome.

The city of Rome during its Republican phase was characterized, in part, by monumental architectural dedications made by leading, elite citizens, often in connection with key political or military accomplishments. Temples were a particularly popular choice in this category given their visibility and their utility for public events both sacred and secular.

The Temple of Portunus is located adjacent to a circular temple of the Corinthian order, now attributed to Herakles Victor. The assignation of the Temple of Portunus has been debated by scholars, with some referring to the temple as belonging to Fortuna Virilis (an aspect of the God Fortuna). This is now a minority view. The festival in honor of Portunus (the Portunalia) was celebrated on 17 August.

The Temple’s plan and construction

The temple has a rectangular footprint, measuring roughly 10.5 x 19 meters (36 x 62 Roman feet). Its plan may be referred to as pseudoperipteral, instead of a having a free-standing colonnade, or row of columns, on all four sides, the temple instead only has free-standing columns on its façade with engaged columns on its flanks and rear.

The pronaos (porch) of the temple supports an Ionic colonnade measuring four columns across by two columns deep, with the columns carved from travertine. The Ionic order can be most easily seen in the scroll-shaped (volute) capitals. There are five engaged columns on each side, and four across the back.

Overall the building has a composite structure, with both travertine and tufa being used for the superstructure (tufa is a type of stone consisting of consolidated volcanic ash, and travertine is a form of limestone). A stucco coating would have been applied to the tufa, giving it an appearance closer to that of the travertine.

The temple’s design incorporates elements from several architectural traditions. From the Italic tradition it takes its high podium (one ascends stairs to enter the pronaos), and strong frontality. From Hellenistic architecture comes the Ionic order columns, the engaged pilasters and columns. The use of permanent building materials, stone (as opposed to the Italic custom of superstructures in wood, terracotta, and mudbrick), also reflects changing practices. The temple itself represents the changing realities and shifting cultural landscape of the Mediterranean world at the close of the first millennium B.C.E.

The temple of Portunus resides on the Forum Boarium, a public space that was the site of the primary harbor of Rome. While the temple of Portunus is a bit smaller than other temples in the Forum Boarium and the adjacent Forum Holitorium, it fits into a general typology of Late Republican temple building.

The temple of Portunus finds perhaps its closest contemporary parallel in the Temple of the Sibyl at Tibur (modern Tivoli) which dates c. 150-125 B.C.E. The temple type embodied by the Temple of Portunus may also be found in Iulio-Claudian temple buildings such as the Maison Carrée at Nîmes in southern France.

Preservation and current state

The Temple of Portunus is obviously in an excellent state of preservation. In 872 C.E. the ancient temple was re-dedicated as a Christian shrine sacred to Santa Maria Egyziaca (Saint Mary of Egypt), leading to the preservation of the structure. The architecture has inspired many artists and architects over the centuries, including Andrea Palladio who studied the structure in the sixteenth century.

Neo-Classical architects were inspired by the form of the Temple of Portunus and it led to the construction of the Temple of Harmony, a folly in Somerset, England, dating to 1767 (below).

The Temple of Portunus is important not only for its well preserved architecture and the inspiration that architecture has fostered, but also as a reminder of what the built landscape of Rome was once like – dotted with temples large and small that became foci of a great deal of activity in the life of the city. Those temples that survive are reminders of that vibrancy as well as of the architectural traditions of the Romans themselves.

Backstory

By Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

The Temple of Portunus was put on the World Monuments Watch list in 2006. Overseen by the World Monuments Fund, this list highlights “cultural heritage sites around the world that are at risk from the forces of nature or the impact of social, political, and economic change,” providing them with “an opportunity to attract visibility, raise public awareness, foster local engagement in their protection, leverage new resources for conservation, advance innovation, and demonstrate effective solutions.”

Together with the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma and grants from private funders, the World Monuments Fund sponsored a restoration of the Temple of Portunus beginning in 2000. The temple had been partially restored and conservation measures put in place in the 1920s, but the activities undertaken in the last two decades utilized the latest technologies to complete a full restoration of the interior and exterior of the building. This included the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes, replacement of the roof (incorporating ancient roof tiles), anti-seismic measures, and the cleaning and restoration of the pediment, columns, and exterior walls. The newly-restored temple opened to the public in 2014.

The Temple of Portunus is one of the best-preserved examples of Roman Republican architecture, and efforts like those of the World Monuments Fund are ensuring that it continues to survive intact.

Maison Carrée

This well-preserved building in modern-day France is a textbook example of a Vitruvian temple.

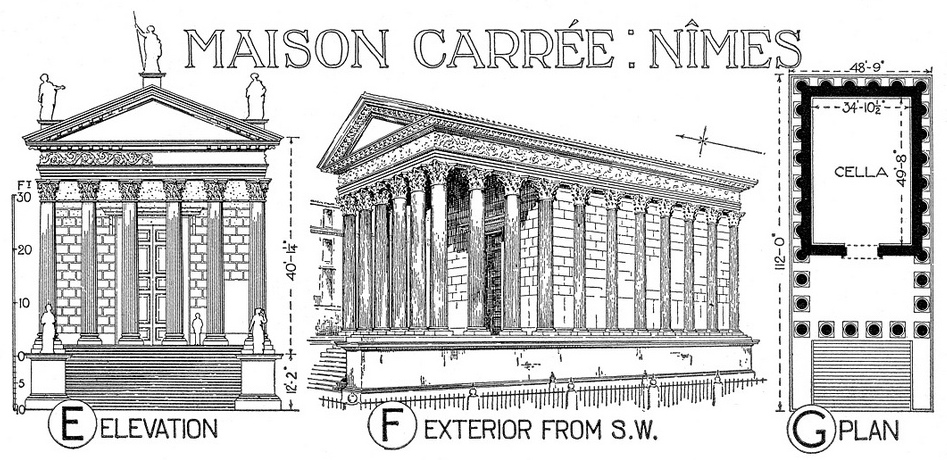

The so-called Maison Carrée or “square house” is an ancient Roman temple located in Nîmes in southern France. Nîmes was founded as a Roman colony (Colonia Nemausus) during the first century B.C.E. The Maison Carrée is an extremely well preserved ancient Roman building and represents a nearly textbook example of a Roman temple as described by the architectural writer Vitruvius.

Design and Plan

The frontal temple is a classic example of the Tuscan style temple as described by Vitruvius (who wrote On Architecture in the first century B.C.E.). This means that the building has a single cella (cult room), a deep porch, a frontal, axial orientation, and sits atop a high podium. The podium of the Maison Carrée rises to a height of 2.85 meters; the footprint of the temple measures 26.42 by 13.54 meters at the base.

The building is executed in the Corinthian order (easily identified by the acanthus leaf motifs on the capital) and is hexastyle in its plan (meaning it has six columns across the façade); twenty engaged columns line the flanks, yielding a pseudoperipteral arrangement (the front columns are free-standing but the columns on the sides and back are engaged, that is, attached to the wall).

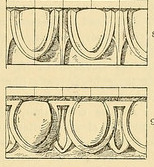

The temple has a very deep pronaos (porch). The superstructure is decorated with egg-and-dart motifs, with the architrave divided into three zones. The deep porch which puts an emphasis on the temple front and the pseudoperipteral arrangement clearly differentiate this from an ancient Greek temple.

The temple once carried a dedicatory inscription that was removed in the Middle Ages. Following the reconstruction of the inscription in 1758, scholars believe that the dedication of the building honored Augustus’ grandsons and intended heirs, Caius and Lucius Caesar. The dedicatory inscription read, in translation, “To Gaius Caesar, son of Augustus, Consul; to Lucius Caesar, son of Augustus, Consul designate; to the princes of youth” (CIL XII, 3156). While not especially common within Italy during the time of the Iulio-Claudians, the worship of the emperor and the imperial family was more commonplace in the provinces of the Roman empire.

The late first century B.C.E. Temple of Augustus and Livia in located in Vienne, France (an ancient settlement of the Allobroges that received a Roman colony) is very similar in plan to the Maison Carrée. This temple was originally dedicated to Augustus alone, but in 41 C.E. the emperor Claudius re-dedicated the building to include Livia, his grandmother (and the wife of Augustus). Taken together these temples show us not only well preserved examples of early Imperial architecture but they also show the degree to which local elites would invest in monumental construction in order to celebrate the emperor and his family members. Just as honorific temples at Rome were sponsored by elites, construction in the provinces also often relied on elite members of the community to fill the role of artistic patron.

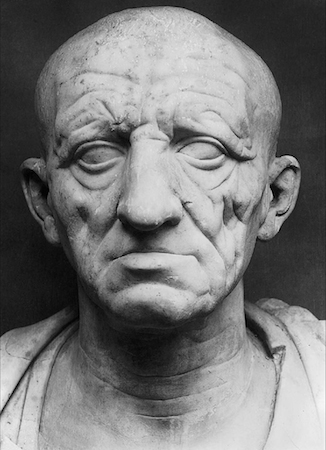

Head of a Roman Patrician

Seemingly wrinkled and toothless, with sagging jowls, the face of a Roman aristocrat stares at us across the ages. In the aesthetic parlance of the Late Roman Republic, the physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating the way in which the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors. While this representational strategy might seem unusual in the post-modern world, in the waning days of the Roman Republic it was an effective means of competing in an ever more complex socio-political arena.

The portrait

This portrait head, now housed in the Palazzo Torlonia in Rome, Italy, comes from Otricoli (ancient Ocriculum) and dates to the middle of the first century B.C.E. The name of the individual depicted is now unknown, but the portrait is a powerful representation of a male aristocrat with a hooked nose and strong cheekbones. The figure is frontal without any hint of dynamism or emotion—this sets the portrait apart from some of its near contemporaries. The portrait head is characterized by deep wrinkles, a furrowed brow, and generally an appearance of sagging, sunken skin—all indicative of the veristic style of Roman portraiture.

Verism

Verism can be defined as a sort of hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity. In the case of Roman Republican portraiture, middle age males adopt veristic tendencies in their portraiture to such an extent that they appear to be extremely aged and care worn. This stylistic tendency is influenced both by the tradition of ancestral imagines as well as a deep-seated respect for family, tradition, and ancestry. The imagines were essentially death masks of notable ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family. In the case of aristocratic families these wax masks were used at subsequent funerals so that an actor might portray the deceased ancestors in a sort of familial parade (Polybius History 6.53.54). The ancestor cult, in turn, influenced a deep connection to family. For Late Republican politicians without any famous ancestors (a group famously known as ‘new men’ or ‘homines novi’) the need was even more acute—and verism rode to the rescue. The adoption of such an austere and wizened visage was a tactic to lend familial gravitas to families who had none—and thus (hopefully) increase the chances of the aristocrat’s success in both politics and business. This jockeying for position very much characterized the scene at Rome in the waning days of the Roman Republic and the Otricoli head is a reminder that one’s public image played a major role in what was a turbulent time in Roman history.

Portraiture of the Roman Republic

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in the Roman Republic is due to Roman values , customs, and political life.

As with other forms of Roman art, portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subjects with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the faces of the portraits often display incredible detail and likeness, the subjects’ bodies are idealized and do not correspond to the age shown in the face.

This photo at the left shows the statue, Portrait of a Roman General. He wears a toga that shows his bare chest and idealized abdominal muscles. He stands with one leg bent and hidden under the toga.

The photo below shows the Bust of an Old Man. His face is realistic and life like with deep wrinkles in his forehead, crow’s feet wrinkles around his eyes, and deep lines around his mouth.

The popularity and usefulness of verism appears to derive from the need to have a recognizable image. Veristic portrait busts provided a means of reminding people of distinguished ancestors or of displaying one’s power, wisdom, experience, and authority. Statues were often erected of generals and elected officials in public forums—and a veristic image ensured that a passerby would recognize the person when they actually saw them.

The Late Republic

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish in the first century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire, and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of the portraits and their use.

The portraits of Pompey are not fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great . This similarity served to link Pompey visually with the likeness of Alexander and to remind people that he possessed similar characteristics and qualities.

The portraits of Julius Caesar are more veristic than those of Pompey. Despite staying closer to stylistic convention, Caesar was the first man to mint coins with his own likeness printed on them. In the decades prior to this, it had become increasingly common to place an illustrious ancestor on a coin, but putting a living person—especially oneself—on a coin departed from Roman propriety. By circulating coins issued with his image, Caesar directly showed the people that they were indebted to him for their own prosperity and therefore should support his political pursuits.

Augustus of Primaporta

Augustus and the power of images

Today, politicians think very carefully about how they will be photographed. Think about all the campaign commercials and print ads we are bombarded with every election season. These images tell us a lot about the candidate, including what they stand for and what agendas they are promoting. Similarly, Roman art was closely intertwined with politics and propaganda. This is especially true with portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire; Augustus invoked the power of imagery to communicate his ideology.

Augustus of Primaporta

One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is the so-called Augustus of Primaporta of 20 B.C.E. (the sculpture gets its name from the town in Italy where it was found in 1863). At first glance this statue might appear to simply resemble a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general, but this sculpture also communicates a good deal about the emperor’s power and ideology. In fact, in this portrait Augustus shows himself as a great military victor and a staunch supporter of Roman religion. The statue also foretells the 200 year period of peace that Augustus initiated, called the Pax Romana.

Recalling the Golden Age of ancient Greece

In this marble freestanding sculpture, Augustus stands in a contrapposto pose (a relaxed pose where one leg bears weight). The emperor wears military regalia and his right arm is outstretched, demonstrating that the emperor is addressing his troops. We immediately sense the emperor’s power as the leader of the army and a military conqueror.

Delving further into the composition of the Primaporta statue, a distinct resemblance to Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, a Classical Greek sculpture of the fifth century B.C.E., is apparent. Both have a similar contrapposto stance and both are idealized. That is to say that both Augustus and the Spear-Bearer are portrayed as youthful and flawless individuals: they are perfect. The Romans often modeled their art on Greek predecessors. This is significant because Augustus is essentially depicting himself with the perfect body of a Greek athlete: he is youthful and virile, despite the fact that he was middle-aged at the time of the sculpture’s commissioning. Furthermore, by modeling the Primaporta statue on such an iconic Greek sculpture created during the height of Athens’ influence and power, Augustus connects himself to the Golden Age of that previous civilization.

The cupid and dolphin

So far the message of the Augustus of Primaporta is clear: he is an excellent orator and military victor with the youthful and perfect body of a Greek athlete. Is that all there is to this sculpture? Definitely not! The sculpture contains even more symbolism. First, at Augustus’ right leg is cupid figure riding a dolphin.

The dolphin became a symbol of Augustus’ great naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, a conquest that made Augustus the sole ruler of the Empire. The cupid astride the dolphin sends another message too: that Augustus is descended from the gods. Cupid is the son of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Julius Caesar, the adoptive father of Augustus, claimed to be descended from Venus and therefore Augustus also shared this connection to the gods.

The breastplate

Finally, Augustus is wearing a cuirass, or breastplate, that is covered with figures that communicate additional propagandistic messages. Scholars debate over the identification over each of these figures, but the basic meaning is clear: Augustus has the gods on his side, he is an international military victor, and he is the bringer of the Pax Romana, a peace that encompasses all the lands of the Roman Empire.

In the central zone of the cuirass are two figures, a Roman and a Parthian. On the right, the enemy Parthian returns military standards. This is a direct reference to an international diplomatic victory of Augustus in 20 B.C.E., when these standards were finally returned to Rome after a previous battle.

Surrounding this central zone are gods and personifications. At the top are Sol and Caelus, the sun and sky gods respectively. On the sides of the breastplate are female personifications of countries conquered by Augustus. These gods and personifications refer to the Pax Romana. The message is that the sun is going to shine on all regions of the Roman Empire, bringing peace and prosperity to all citizens. And of course, Augustus is the one who is responsible for this abundance throughout the Empire.

Beneath the female personifications are Apollo and Diana, two major deities in the Roman pantheon; clearly Augustus is favored by these important deities and their appearance here demonstrates that the emperor supports traditional Roman religion. At the very bottom of the cuirass is Tellus, the earth goddess, who cradles two babies and holds a cornucopia. Tellus is an additional allusion to the Pax Romana as she is a symbol of fertility with her healthy babies and overflowing horn of plenty.

Not simply a portrait

The Augustus of Primaporta is one of the ways that the ancients used art for propagandistic purposes. Overall, this statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus’ connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Ara Pacis Augustae

The Roman state religion in microcosm

The festivities of the Roman state religion were steeped in tradition and ritual symbolism. Sacred offerings to the gods, consultations with priests and diviners, ritual formulae, communal feasting—were all practices aimed at fostering and maintaining social cohesion and communicating authority. It could perhaps be argued that the Ara Pacis Augustae—the Altar of Augustan Peace—represents in luxurious, stately microcosm the practices of the Roman state religion in a way that is simultaneously elegant and pragmatic.

Vowed on July 4, 13 B.C.E., and dedicated on January 30, 9 B.C.E., the monument stood proudly in the Campus Martius in Rome (a level area between several of Rome’s hills and the Tiber River). It was adjacent to architectural complexes that cultivated and proudly displayed messages about the power, legitimacy, and suitability of their patron—the emperor Augustus. Now excavated, restored, and reassembled in a sleek modern pavilion designed by architect Richard Meier (2006), the Ara Pacis continues to inspire and challenge us as we think about ancient Rome.

Augustus himself discusses the Ara Pacis in his epigraphical memoir, Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“Deeds of the Divine Augustus”) that was promulgated upon his death in 14 C.E. Augustus states “When I returned to Rome from Spain and Gaul, having successfully accomplished deeds in those provinces … the senate voted to consecrate the altar of August Peace in the Campus Martius … on which it ordered the magistrates and priests and Vestal virgins to offer annual sacrifices” (Aug. RG 12).

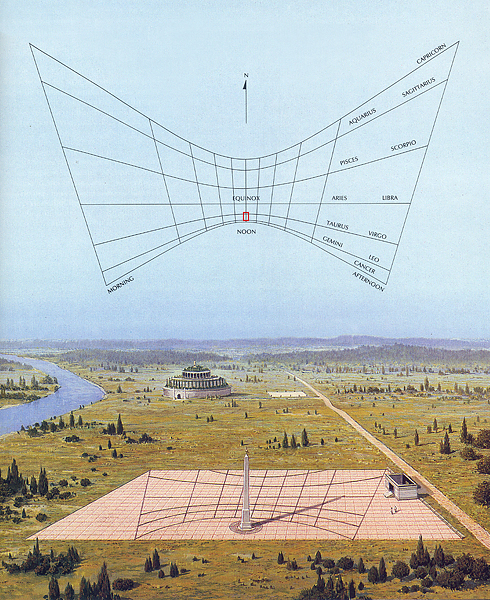

An open-air altar for sacrifice

The Ara Pacis is, at its simplest, an open-air altar for blood sacrifice associated with the Roman state religion. The ritual slaughtering and offering of animals in Roman religion was routine, and such rites usually took place outdoors. The placement of the Ara Pacis in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) along the Via Lata (now the Via del Corso) situated it close to other key Augustan monuments, notably the Horologium Augusti (a giant sundial) and the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The significance of the topographical placement would have been quite evident to ancient Romans. This complex of Augustan monuments made a clear statement about Augustus’ physical transformation of Rome’s urban landscape. The dedication to a rather abstract notion of peace (pax) is significant in that Augustus advertises the fact that he has restored peace to the Roman state after a long period of internal and external turmoil.

The altar (ara) itself sits within a monumental stone screen that has been elaborated with bas relief (low relief) sculpture, with the panels combining to form a programmatic mytho-historical narrative about Augustus and his administration, as well as about Rome’s deep roots. The altar enclosure is roughly square while the altar itself sits atop a raised podium that is accessible via a narrow stairway.

The Outer screen—processional scenes

Processional scenes occupy the north and south flanks of the altar screen. The solemn figures, all properly clad for a rite of the state religion, proceed in the direction of the altar itself, ready to participate in the ritual. The figures all advance toward the west. The occasion depicted would seem to be a celebration of the peace (Pax) that Augustus had restored to the Roman empire. In addition four main groups of people are evident in the processions: (1) the lictors (the official bodyguards of magistrates), (2) priests from the major collegia of Rome, (3) members of the Imperial household, including women and children, and (4) attendants. There has been a good deal of scholarly discussion focused on two of three non-Roman children who are depicted.

The north processional frieze, made up of priests and members of the Imperial household, is comprised of 46 figures. The priestly colleges (religious associations) represented include the Septemviri epulones (“seven men for sacrificial banquets”—they arranged public feasts connected to sacred holidays), whose members here carry an incense box (image above), and the quindecimviri sacris faciundis (“fifteen men to perform sacred actions”— their main duty was to guard and consult the Sibylline books (oracular texts) at the request of the Senate). Members of the imperial family, including Octavia Minor, follow behind.

A good deal of modern restoration has been undertaken on the north wall, with many heads heavily restored or replaced. The south wall of the exterior screen depicts Augustus and his immediate family. The identification of the individual figures has been the source of a great deal of scholarly debate. Depicted here are Augustus (damaged, he appears at the far left in the image above) and Marcus Agrippa (friend, son-in-law, and lieutenant to Augustus, he appears, hooded, image below), along with other members of the imperial house. All of those present are dressed in ceremonial garb appropriate for the state sacrifice. The presence of state priests known as flamens (flamines) further indicate the solemnity of the occasion.

A running, vegetal frieze runs parallel to the processional friezes on the lower register. This vegetal frieze emphasizes the fertility and abundance of the lands, a clear benefit of living in a time of peace.

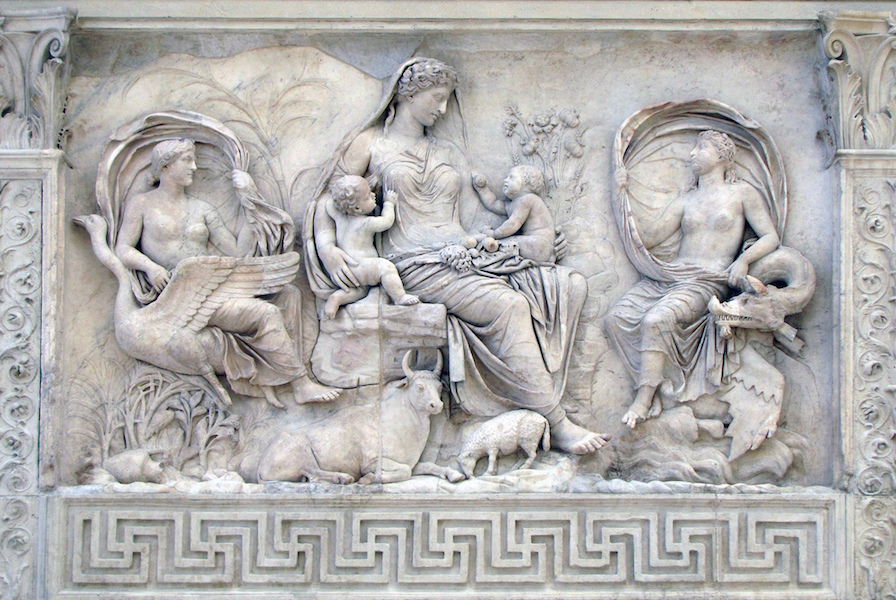

Mythological panels

Accompanying the processional friezes are four mythological panels that adorn the altar screen on its shorter sides. Each of these panels depicts a distinct scene:

- a scene of a bearded male making sacrifice (below)

- a scene of seated female goddess amid the fertility of Italy (also below)

- a fragmentary scene with Romulus and Remus in the Lupercal grotto (where these two mythic founders of Rome were suckled by a she-wolf)

- and a fragmentary panel showing Roma (the personification of Rome) as a seated goddess.

Since the early twentieth century, the mainstream interpretation of the sacrifice panel (above) has been that the scene depicts the Trojan hero Aeneas arriving in Italy and making a sacrifice to Juno. A recent re-interpretation offered by Paul Rehak argues instead that the bearded man is not Aeneas, but Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king. In Rehak’s theory, Numa, renowned as a peaceful ruler and the founder of Roman religion, provides a counterbalance to the warlike Romulus on the opposite panel.

The better preserved panel of the east wall depicts a seated female figure (above) who has been variously interpreted as Tellus (the Earth), Italia (Italy), Pax (Peace), as well as Venus. The panel depicts a scene of human fertility and natural abundance. Two babies sit on the lap of the seated female, tugging at her drapery. Surrounding the central female is the natural abundance of the lands and flanking her are the personifications of the land and sea breezes. In all, whether the goddess is taken as Tellus or Pax, the theme stressed is the harmony and abundance of Italy, a theme central to Augustus’ message of a restored peaceful state for the Roman people—the Pax Romana.

The Altar

The altar itself (below) sits within the sculpted precinct wall. It is framed by sculpted architectural mouldings with crouching gryphons surmounted by volutes flanking the altar. The altar was the functional portion of the monument, the place where blood sacrifice and/or burnt offerings would be presented to the gods.

Implications and interpretation

The implications of the Ara Pacis are far reaching. Originally located along the Via Lata (now Rome’s Via del Corso), the altar is part of a monumental architectural makeover of Rome’s Campus Martius carried out by Augustus and his family. Initially the makeover had a dynastic tone, with the Mausoleum of Augustus near the river. The dedication of the Horologium (sundial) of Augustus and the Ara Pacis, the Augustan makeover served as a potent, visual reminder of Augustus’ success to the people of Rome. The choice to celebrate peace and the attendant prosperity in some ways breaks with the tradition of explicitly triumphal monuments that advertise success in war and victories won on the battlefield. By championing peace—at least in the guise of public monuments—Augustus promoted a powerful and effective campaign of political message making.

Rediscovery

The first fragments of the Ara Pacis emerged in 1568 beneath Rome’s Palazzo Chigi near the basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina. These initial fragments came to be dispersed among various museums, including the Villa Medici, the Vatican Museums, the Louvre, and the Uffizi. It was not until 1859 that further fragments of the Ara Pacis emerged. The German art historian Friedrich von Duhn of the University of Heidelberg is credited with the discovery that the fragments corresponded to the altar mentioned in Augustus’ Res Gestae. Although von Duhn reached this conclusion by 1881, excavations were not resumed until 1903, at which time the total number of recovered fragments reached 53, after which the excavation was again halted due to difficult conditions. Work at the site began again in February 1937 when advanced technology was used to freeze approximately 70 cubic meters of soil to allow for the extraction of the remaining fragments. This excavation was mandated by the order of the Italian government of Benito Mussolini and his planned jubilee in 1938 that was designed to commemorate the 2,000th anniversary of Augustus’ birth.

Mussolini and Augustus

The revival of the glory of ancient Rome was central to the propaganda of the Fascist regime in Italy during the 1930s. Benito Mussolini himself cultivated a connection with the personage of Augustus and claimed his actions were aimed at furthering the continuity of the Roman Empire. Art, architecture, and iconography played a key role in this propagandistic “revival”. Following the 1937 retrieval of additional fragments of the altar, Mussolini directed architect Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo to construct an enclosure for the restored altar adjacent to the ruins of the Mausoleum of Augustus near the Tiber river, creating a key complex for Fascist propaganda. Newly built Fascist palaces, bearing Fascist propaganda, flank the space dubbed “Piazza Augusto Imperatore” (“Plaza of the emperor Augustus”). The famous Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“Deeds of the Divine Augustus”) was re-created on the wall of the altar’s pavilion. The concomitant effect was meant to lead the viewer to associate Mussolini’s accomplishments with those of Augustus himself.

The Ara Pacis and Richard Meier

The firm of architect Richard Meier was engaged to design and execute a new and improved pavilion to house the Ara Pacis and to integrate the altar with a planned pedestrian area surrounding the adjacent Mausoleum of Augustus.

Between 1995 and the dedication of the new pavilion in 2006 Meier crafted the modernist pavilion that capitalizes on glass curtain walls granting visitors views of the Tiber river and the mausoleum while they perambulate in the museum space focused on the altar itself. The Meier pavilion has not been well-received, with some critics immediately panning it and some Italian politicians declaring that it should be dismantled. The museum has also been the victim of targeted vandalism.

Enduring monumentality

The Ara Pacis Augustae continues both to engage us and to incite controversy. As a monument that is the product of a carefully constructed ideological program, it is highly charged with socio-cultural energy that speaks to us about the ordering of the Roman world and its society—the very Roman universe.

Augustus had a strong interest in reshaping the Roman world (with him as its sole leader) but he had to be cautious about how radical those changes seemed to the Roman populace. While he defeated enemies, both foreign and domestic, he was concerned about being perceived as too authoritarian–he did not wish to be labeled as a king (rex) for fear that this would be too much for the Roman people to accept. So, the Augustan scheme involved a declaration that Rome’s republican government had been “restored” by Augustus and he styled himself as the leading citizen of the republic (princeps). These political and ideological motives then influence and guide the creation of his program of monumental art and architecture. These monumental forms, of which the Ara Pacis is a prime example, served to both create and reinforce these Augustan messages.

The story of the Ara Pacis becomes even more complicated since it is an artifact that then was placed in the service of ideas in the modern age. This results in its identity becoming a hybridized mixture of Classicism, Fascism, and modernism—all difficult to interpret in a postmodern reality. It is important to remember that the sculptural reliefs were created in the first place to be easily legible so that the viewer could understand the messages of Augustus and his circle without the need to read elaborate texts. Augustus pioneered the use of such ideological messages that relied on clear iconography to get their message across. A great deal was at stake for Augustus and it seems, by virtue of history, that the political choices he made proved prudent. The messages of the Pax Romana, of a restored state, and of Augustus as a leading republican citizen, are all part of an effective and carefully constructed veneer.

Portrait of Vespasian

In ancient Rome, official portraits were an extremely important way for emperors to reach out to their subjects, and their public image was defined by them. As hundreds of surviving imperial statues show, there were only three ways in which the emperor could officially be represented: in the battle dress of a general; in a toga, the Roman state civilian costume; or nude, likened to a god. These styles powerfully and effectively evoked the emperor’s role as commander-in-chief, magistrate or priest, and finally as the ultimate embodiment of divine providence.

Portrait of the emperor: A soldier and a wit

This naturalistic portrait of the emperor Vespasian (reigned 69-79 C.E.) clearly shows the lined complexion of this battle-hardened emperor, and also the curious ‘strained expression’ which the Roman writer Suetonius said he had at all times. The loss of the nose is characteristic of the damage often suffered by ancient statues, either through deliberate mutilation or through falling or being toppled from their base.

Vespasian was born in the Roman town of Reate (Rieti), about forty miles (sixty-five kilometers) north-west of Rome in the Sabine Hills. Vespasian distinguished himself in military campaigns in Britain and later became a trusted aide of the emperor Nero. Together with one of his sons, Titus, Vespasian conquered Judaea in 75 C.E. and celebrated with a magnificent triumphal procession through Rome. Part of the event, in particular the displaying of the seven-branched candlestick or “Menorah” from the Temple at Jerusalem, is shown on the Arch of Titus, in Rome (above). The proceeds from the conquest of Judaea provided funds for the building of the Colosseum and other famous buildings in Rome.

Vespasian was known for his wit as well as his military skills. When, during one of his attempts to boost the treasury, Vespasian raised a tax on public urinals. Titus complained that this was below imperial dignity. Vespasian is said to have held out a handful of coins from the new tax and said “Now, do these smell any different?” Even on his death bed Vespasian’s wit did not desert him. He was perhaps parodying the idea of the deification of emperors, when he said “Oh dear, I think I’m becoming a god.”

Roman portrait sculptures

Portrait sculptures are one of the great legacies of Roman art. Busts and statues portraying men, women and children from most ranks of society were set up in houses, tombs and public buildings throughout the Roman Empire. Sculptures of emperors and magistrates were often thought to embody personal authority, whereas many of the portraits representing private citizens were intended as memorials to the dead.

Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater):A CONVERSATION

By Valentina Follo, Dr. Beth: Harris, and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Colosseum in Rome between Beth: Harris, Steven Zucker, and Valentina Follo (courtesy of Context Travel). To watch the video: https://youtu.be/9wguQaBYKec.

Valentina: Imagine how beautiful it must have been, this square with all these monumental arches, carved with travertine, and all the statues, and beautiful fountains spilling out water, reflecting the light on the travertine.

Beth: So we might think about this more like the way we think today about Lincoln Center.

Valentina: Exactly.

Beth: With fountains in the middle and gleaming stone.

Steven: Should we start out by talking a little bit about the structure and how it was built?

Valentina: You have to imagine the Colosseum as a gigantic donut. The inside is the arena. “Arena” originally in Latin meant sand. On the floor where gladiators were fighting, they used sand to absorb blood and body fluids, like a gigantic cat litter box. Between different fights, they could simply clean very easily. The original name of this building was not “Colosseum.” “Colosseum” is a nickname given later, not because it was a colossal monument, but because it was located in the proximity of a colossal statue, originally of Nero, that was part of the decoration of his house. And so with time, the nickname was given by this proximity. Originally, it was actually a Flavian Amphitheater. And this is something very typical, even if you think about American monuments. You have the Lincoln Center. You have the Rockefeller Center. They are connected to the name of the family that paid for the building. The Flavian family paid for the building of the Colosseum. Flavian Amphitheater is just a technical name for the shape. It simply means, in Greek, “a double theater.”

Steven: The original Greek theaters were actually semicircles with a flat end by the stage. And so this is really just fusing those two together.

Valentina: By using arches and concrete, Romans were able to build an amphitheater, even a double theater, with seats on a flat surface. The engineering behind it is absolutely astonishing considering that it was only built in 10 years. The Colosseum could hold between 50,000 and 80,000 people. If you look at the actual top part of each of the ground-floor arches, you see a Roman number. They are very dark and dilapidated. You can see a 23, and then there’s a 24, and there is a 25. They’re progressive. And this number would have been written on the ticket and given to the people. It’s like a modern stadium. You would have an assigned seat.

Beth: A gate number.

Valentina: Also, the seat, because it was extremely important for the Romans. And the seats were assigned according to their status. So you had the most important people close to the arena, and the least important—being the women—on the top floor. You have three stories of arches, and then another story, a fourth floor, with windows. So it’s closed with small windows inside it. And if you look at these arches, the arches are framed by columns. At the bosom part, you have what’s called Tuscanic. It’s similar to Doric, but it’s more a local, Italic style.

Steven: It’s even a little simpler than Doric, it seems.

Valentina: Yeah, it’s also the base. Doric columns do not have a base, while Tuscanic columns do have a base.

Steven: And they’re not fluted, as well.

Valentina: No. Then you go to the Ionic columns on the second story. The Ionic columns, actually, were considered the most feminine of the columns. Their proportions were more, slender with the volutes on the top.

Steven: And the women sat higher, as well.

Valentina: Exactly. On the top floor, you’ve got the Corinthian. They are based on the acanthus plant. And it’s indigenous in Rome. You can find it in many gardens. It’s very nice with these green leaves. And so it’s an imitation of a piece of stone covered with leaves of grass. Inside of each of the arches on the second and third floor, there would be a statue. On the top floor, there would have been probably bronze shields, alternating the windows. Again, we imagine the Colosseum as a donut. The outside circle was done with blocks of travertine. The inside of the donut was done with a core of concrete.

Steven: The Romans had really perfected concrete, and really were the first to use it as this real structural material. That was critical for their ability to create structures of this size. Also something like the Pantheon.

Valentina: The development of concrete was crucial for two main reasons. The first one is if you work with cut stone—marble, travertine, even tufa stone—you need specialized workers because you need to know how to cut the stone. If you cut it the wrong way, the stone will crumble into your hands. With concrete, it made it possible for unspecialized workers to produce something more sturdy. At the same time, it’s less expensive. To quarry blocks of marble is not cheap. Concrete could be assembled everywhere. You just need a little mortar and few pieces of stone to make aggregate and water. So it’s very easy, but at the same time, it’s more elastic. With concrete, you get a sort of elasticity and then you can mold space. Because it’s something liquid, you can simply mold it the way you want it.

Beth: And so the idea would be to take a wooden framework that framed out the space that you wanted, and then to pour concrete into that wooden mold.

Valentina: Exactly. And then it would be covered with the decoration. It could be bricks, stucco, whatever you wanted.

Steven: So it really allowed for far more monumental structures, and that would then be economically, and physically, feasible.

Valentina: And less expensive and quick. 10 years to build the Colosseum is quite an accomplishment because they used mostly concrete.

Beth: Also thinking about architecture in a new way, in terms of shaping an interior space.

Valentina: Particularly the interior because if you look at Greek architecture, the inside of a Greek temple is quite narrow. If you think about the Pantheon, you are in this amazing sphere. That’s why they really invented it—they are molding not the outside, but inside, to be able to produce a vault that could permit a space free of standing columns in the middle to support the roof.

Beth: Moving away from post-and-lintel architecture to an interior space.

Steven: Which really, in a sense, almost doubled the architectural vocabulary and created an advancement over a system that had existed for thousands of years.

Valentina: Romans employed concrete on such a scale that permitted them to build wherever they wanted. They were not forced by space. Greeks could not build a theater wherever they wanted. They needed a slope. So what if you were living in a city without slopes? No theater for you, right? Romans were able to create a theater, or an amphitheater, or a circus, or a bath complex wherever they wanted.

Steven: It’s true that the Greeks seemed to use natural features in a more passive way, whereas the Romans seemed to shape the landscape much more aggressively. You talked about the fact that there had been a lake here. Let’s drain the lake. We’re putting a building here. Nature becomes in the service of man rather than vice versa.

Valentina: That’s actually a very good point. The fact is that they wanted to be able to shape their space.

Beth: It’s the idea of urban planning—you could build a city the way you wanted to, and not just be subject to the landscape that was there.

Steven: But I think there’s this really important way in which the Romans were thinking of themselves as powers in the landscape, having that sort of dominance. It seems to me that the Romans shaped, in a way, that speaks that notion of their own inherent strength.

Valentina: What was different about Roman society—they were not racist in the sense they were looking at the color of your skin—it was a multicultural society. There were Romans from Africa, Romans from Turkey, Romans from Germany. What made it different was if were you a citizen or not. If you were not a citizen, you were nobody. But if you were a citizen, then the color of your skin was not important.

Steven: But there were fine distinctions, even within citizenship?

Valentina: Of course, there were social classes. An interesting aspect was that you could move along the social scale. While for Greeks, you could not even acquire citizenship. It was extremely rare to obtain citizenship. For the Romans, even a slave could become first a free man. And then his children will become a full citizen of Rome. It’s like America, if you think about America, like second-generation immigrants. It’s the same idea. They realized that just being able to move and being able to give people a chance in life could make all the difference in the economy.

The Forum and Markets of Trajan

An emperor worth celebrating

Marcus Ulpius Traianus, now commonly referred to as Trajan, reigned as Rome’s emperor from 98 until 117 C.E. A military man, Trajan was born of mixed stock—part Italic, part Hispanic—into the gens Ulpia (the Ulpian family) in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica (modern Spain) and enjoyed a career that catapulted him to the heights of popularity, earning him an enduring reputation as a “good emperor.”

Trajan was the first in a line of adoptive emperors that concluded with Marcus Aurelius. These emperors were chosen for the “job” based not on bloodlines, but on their suitability for rule; most of them were raised with this role in mind from their youth. This period is often regarded as the height of the Roman empire’s prosperity and stability. The ancient Romans were so fond of Trajan that they officially bestowed upon him the epithetical title optimus princeps or “the best first-citizen.” It is safe to say that the Romans felt Trajan was well worth celebrating—and celebrate him they did. A massive architectural complex—referred to as the Forum of Trajan (Latin: Forum Traiani or, less commonly, Forum Ulpium) was devoted to Trajan’s career and, in particular, his great military successes in his wars against Dacia (now Romania).

Unique under the heavens

The Forum of Trajan was the final, and largest, of Rome’s complex of so-called “Imperial fora”—dubbed by at least one ancient writer as “a construction unique under the heavens” (Amm. Marc. 16.10.15). Fora is the Latin plural of forum—meaning a public, urban square for civic and ritual business. A series of Imperial fora, beginning with Iulius Caesar, had been built adjacent to the earlier Roman Forum by a series of emperors. The Forum of Trajan was inaugurated in 112 C.E., although construction may not have been complete, and was designed by the famed architect Apollodorus of Damascus.

The Forum of Trajan is elegant—it is rife with signs of top-level architecture and decoration. All of the structures, save the two libraries (which were built of brick), were built of stone. There is a great deal of exotic, imported marble and many statues, including gilded examples. The forum was composed of a main square (measuring c. 200 x 120 meters) that was flanked by porticoes (an extended, roofed colonnade), as well as by exedrae (semicircular, recessed spaces) on the eastern (above) and western sides.