8

Dr. Renee M. Gondek; Dr. Jeffrey Becker; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Beth Harris; and Lumen Learning

In this chapter

Introduction: The Ancient Greeks & Their Gods

Geometric & Orientalizing

Archaic

- Attic Black-Figure Amphora with Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game

- Sculpture in the Archaic period

- Lady of Auxerre

Early Classical

High Classical

Late Classical

Hellenistic

Introduction to ancient Greek art

A shared language, religion, and culture

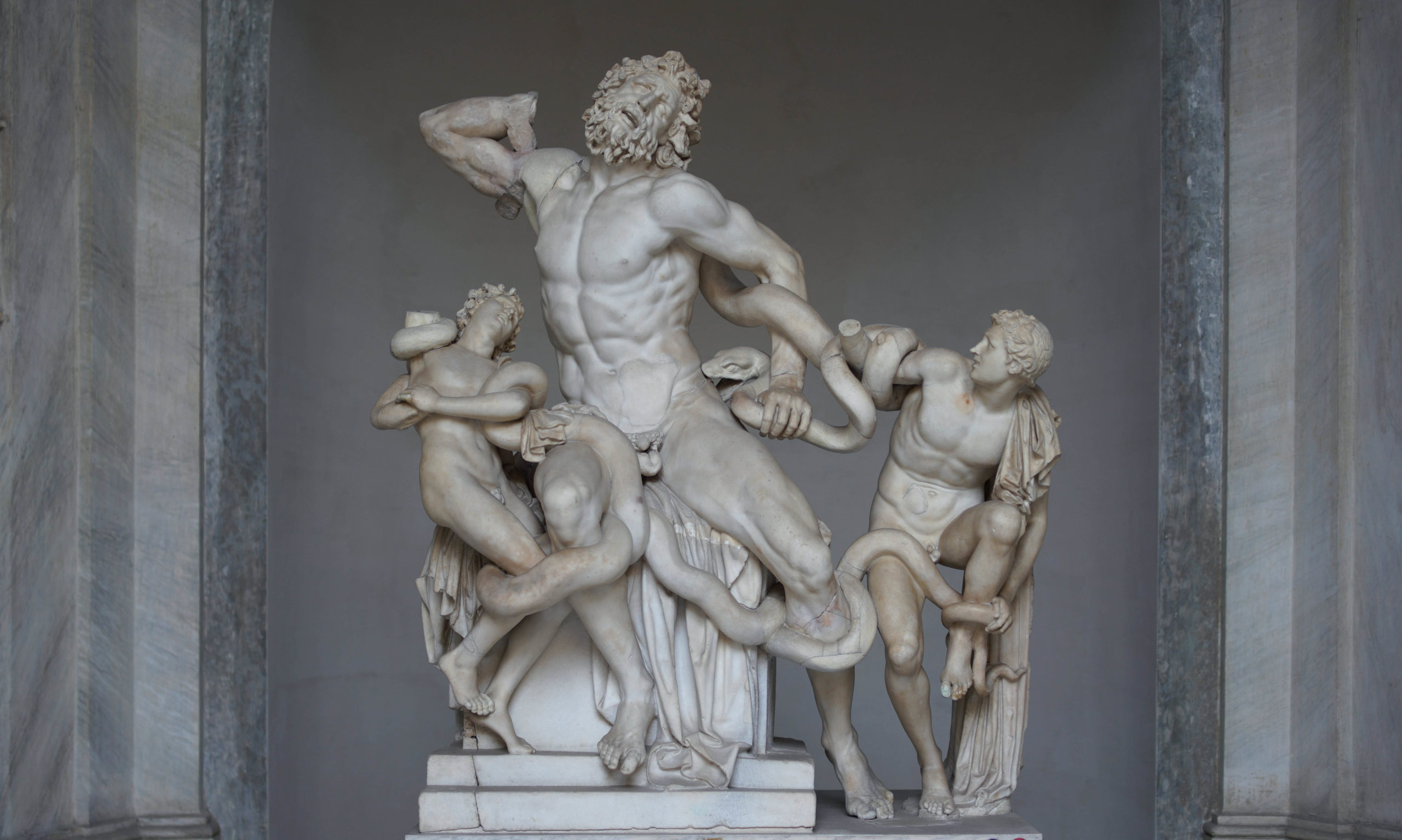

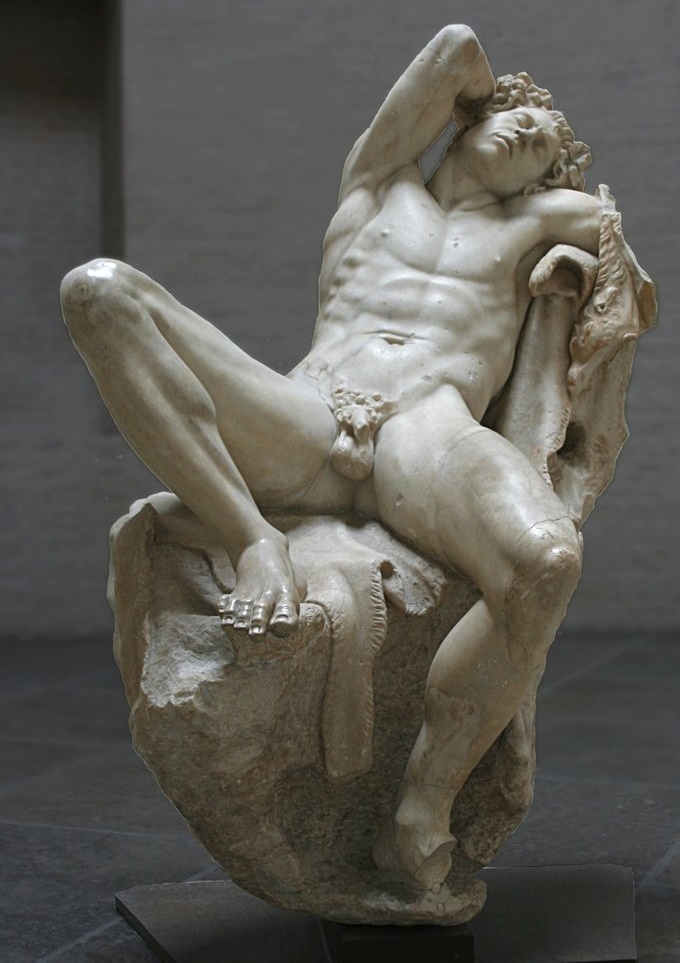

Ancient Greece can feel strangely familiar. From the exploits of Achilles and Odysseus, to the treatises of Aristotle, from the exacting measurements of the Parthenon (image above) to the rhythmic chaos of the Laocoön (image below), ancient Greek culture has shaped our world. Thanks largely to notable archaeological sites, well-known literary sources, and the impact of Hollywood (Clash of the Titans, for example), this civilization is embedded in our collective consciousness—prompting visions of epic battles, erudite philosophers, gleaming white temples, and limbless nudes (we now know the sculptures—even the ones that decorated temples like the Parthenon—were brightly painted, and, of course, the fact that the figures are often missing limbs is the result of the ravages of time).

Dispersed around the Mediterranean and divided into self-governing units called poleis or city-states, the ancient Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture. Strengthening these bonds further were the so-called “Panhellenic” sanctuaries and festivals that embraced “all Greeks” and encouraged interaction, competition, and exchange (for example the Olympics, which were held at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia). Although popular modern understanding of the ancient Greek world is based on the classical art of fifth century B.C.E. Athens, it is important to recognize that Greek civilization was vast and did not develop overnight.

The Dark Ages (c. 1100–c. 800 BCE) to the Orientalizing Period (c. 700–600 BCE)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland was traditionally thought to enter a “Dark Age” that lasted from c. 1100 until c. 800 B.C.E. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but also its numerous achievements (i.e., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). The discovery and continuous excavation of a site known as Lefkandi, however, drastically alters this impression. Located just north of Athens, Lefkandi has yielded an immense apsidal structure (almost fifty meters long), a massive network of graves, and two heroic burials replete with gold objects and valuable horse sacrifices. One of the most interesting artifacts, ritually buried in two separate graves, is a centaur figurine (see photos below). At fourteen inches high, the terracotta creature is composed of a equine (horse) torso made on a potter’s wheel and hand-formed human limbs and features. Alluding to mythology and perhaps a particular story, this centaur embodies the cultural richness of this period.

Similar in its adoption of narrative elements is a vase-painting likely from Thebes dating to c. 730 B.C.E. (see image below). Fully ensconced in the Geometric Period (c. 800-700 B.C.E.), the imagery on the vase reflects other eighth-century artifacts, such as the Dipylon Amphora, with its geometric patterning and silhouetted human forms. Though simplistic, the overall scene on this vase seems to record a story. A man and woman stand beside a ship outfitted with tiers of rowers. Grasping at the stern and lifting one leg into the hull, the man turns back towards the female and takes her by the wrist. Is the couple Theseus and Ariadne? Is this an abduction? Perhaps Paris and Helen? Or, is the man bidding farewell to the woman and embarking on a journey as had Odysseus and Penelope? The answer is unattainable.

In the Orientalizing Period (700-600 B.C.E.), alongside Near Eastern motifs and animal processions, craftsmen produced more nuanced figural forms and intelligible illustrations. For example, terracotta painted plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon (c. 625 B.C.E.) are some of the earliest evidence for architectural decoration in Iron Age Greece. Once ornamenting the surface of this Doric temple (most likely as metopes), the extant panels have preserved various imagery. On one plaque (see image below), a male youth strides towards the right and carries a significant attribute under his right arm—the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa (her face is visible between the right hand and right hip of the striding figure). Not only is the painter successful here in relaying a particular story, but also the figure of Perseus shows great advancement from the previous century. The limbs are fleshy, the facial features are recognizable, and the hat and winged boots appropriately equip the hero for fast travel.

The Archaic Period (c. 600-480/479 B.C.E.)

While Greek artisans continued to develop their individual crafts, storytelling ability, and more realistic portrayals of human figures throughout the Archaic Period, the city of Athens witnessed the rise and fall of tyrants and the introduction of democracy by the statesman Kleisthenes in the years 508 and 507 B.C.E.

Visually, the period is known for large-scale marble kouros (male youth) and kore (female youth) sculptures (see below). Showing the influence of ancient Egyptian sculpture (compare Menkaure and Queen from Ancient Egypt), the kouros stands rigidly with both arms extended at the side and one leg advanced. Frequently employed as grave markers, these sculptural types displayed unabashed nudity, highlighting their complicated hairstyles and abstracted musculature (below left). The kore, on the other hand, was never nude. Not only was her form draped in layers of fabric, but she was also ornamented with jewelry and adorned with a crown. Though some have been discovered in funerary contexts, like Phrasiklea (below right), a vast majority were found on the Acropolis in Athens. Ritualistically buried following desecration of this sanctuary by the Persians in 480 and 479 B.C.E., dozens of korai were unearthed alongside other dedicatory artifacts. While the identities of these figures have been hotly debated in recent times, most agree that they were originally intended as votive offerings to the goddess Athena.

The Classical Period (480/479-323 B.C.E.)

Though experimentation in realistic movement began before the end of the Archaic Period, it was not until the Classical Period that two- and three-dimensional forms achieved proportions and postures that were naturalistic. The “Early Classical Period” (480/479 – 450 B.C.E., also known as the “Severe Style”) was a period of transition when some sculptural work displayed archaizing holdovers. As can be seen in the Kritios Boy, c. 480 B.C.E., the “Severe Style” features realistic anatomy, serious expressions, pouty lips, and thick eyelids. For painters, the development of perspective and multiple ground lines enriched compositions, as can be seen on the Niobid Painter’s vase in the Louvre (below).

During the “High Classical Period” (450-400 B.C.E.), there was great artistic success: from the innovative structures on the Acropolis to Polykleitos’ visual and cerebral manifestation of idealization in his sculpture of a young man holding a spear, the Doryphoros or “Canon” (image below). Concurrently, however, Athens, Sparta, and their mutual allies were embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a bitter conflict that lasted for several decades and ended in 404 B.C.E. Despite continued military activity throughout the “Late Classical Period” (400-323 B.C.E.), artistic production and development continued apace. In addition to a new figural aesthetic in the fourth century known for its longer torsos and limbs, and smaller heads (for example, the Apoxyomenos), the first female nude was produced. Known as the Aphrodite of Knidos, c. 350 B.C.E., the sculpture pivots at the shoulders and hips into an S-Curve and stands with her right hand over her genitals in a pudica (or modest Venus) pose. Exhibited in a circular temple and visible from all sides, the Aphrodite of Knidos became one of the most celebrated sculptures in all of antiquity.

The Hellenistic Period and Beyond (323 B.C.E. – 31 B.C.E.)

- Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E., the Greeks and their influence stretched as far east as modern India. While some pieces intentionally mimicked the Classical style of the previous period such as Eutychides’ Tyche of Antioche (Louvre), other artists were more interested in capturing motion and emotion. For example, on the Great Altar of Zeus from Pergamon (below) expressions of agony and a confused mass of limbs convey a newfound interest in drama.

-

Athena defeats Alkyoneus (detail), The Pergamon Altar, c. 200-150 B.C.E. (Hellenistic Period), 35.64 x 33.4 meters, marble (Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

Architecturally, the scale of structures vastly increased, as can be seen with the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, and some complexes even terraced their surrounding landscape in order to create spectacular vistas as can be seem at the Sanctuary of Asklepios on Kos. Upon the defeat of Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E., the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt and, simultaneously, the Hellenistic Period came to a close. With the Roman admiration of and predilection for Greek art and culture, however, Classical aesthetics and teachings continued to endure from antiquity to the modern era.

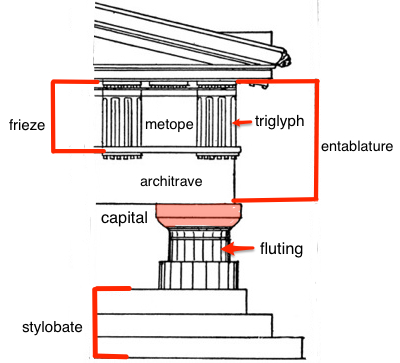

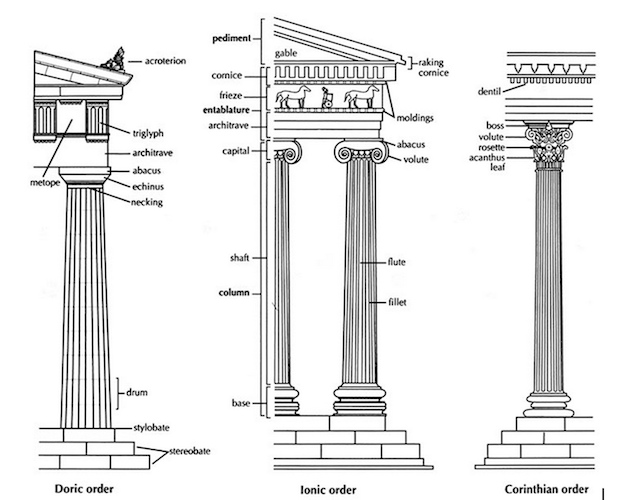

Greek architectural orders

An architectural order describes a style of building. In classical architecture each order is readily identifiable by means of its proportions and profiles, as well as by various aesthetic details. The style of column employed serves as a useful index of the style itself, so identifying the order of the column will then, in turn, situate the order employed in the structure as a whole. The classical orders—described by the labels Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—do not merely serve as descriptors for the remains of ancient buildings, but as an index to the architectural and aesthetic development of Greek architecture itself.

The Doric order

The Doric order is the earliest of the three Classical orders of architecture and represents an important moment in Mediterranean architecture when monumental construction made the transition from impermanent materials (i.e. wood) to permanent materials, namely stone. The Doric order is characterized by a plain, unadorned column capital and a column that rests directly on the stylobate of the temple without a base. The Doric entablature includes a frieze composed of trigylphs (vertical plaques with three divisions) and metopes (square spaces for either painted or sculpted decoration). The columns are fluted and are of sturdy, if not stocky, proportions.

The Doric order emerged on the Greek mainland during the course of the late seventh century B.C.E. and remained the predominant order for Greek temple construction through the early fifth century B.C.E., although notable buildings of the Classical period—especially the canonical Parthenon in Athens—still employ it. By 575 B.C.E the order may be properly identified, with some of the earliest surviving elements being the metope plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon. Other early, but fragmentary, examples include the sanctuary of Hera at Argos, votive capitals from the island of Aegina, as well as early Doric capitals that were a part of the Temple of Athena Pronaia at Delphi in central Greece. The Doric order finds perhaps its fullest expression in the Parthenon (c. 447-432 B.C.E.) at Athens designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates.

The Ionic order

As its names suggests, the Ionic Order originated in Ionia, a coastal region of central Anatolia (today Turkey) where a number of ancient Greek settlements were located. Volutes (scroll-like ornaments) characterize the Ionic capital and a base supports the column, unlike the Doric order. The Ionic order developed in Ionia during the mid-sixth century B.C.E. and had been transmitted to mainland Greece by the fifth century B.C.E. Among the earliest examples of the Ionic capital is the inscribed votive column from Naxos, dating to the end of the seventh century B.C.E.

The monumental temple dedicated to Hera on the island of Samos, built by the architect Rhoikos, c. 570-560 B.C.E., was the first of the great Ionic buildings, although it was destroyed by earthquake in short order. The sixth century B.C.E. Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, a wonder of the ancient world, was also an Ionic design. In Athens the Ionic order influences some elements of the Parthenon (447-432 B.C.E.), notably the Ionic frieze that encircles the cella of the temple. Ionic columns are also employed in the interior of the monumental gateway to the Acropolis known as the Propylaia (c. 437-432 B.C.E.). The Ionic was promoted to an exterior order in the construction of the Erechtheion (c. 421-405 B.C.E.) on the Athenian Acropolis.The Ionic order is notable for its graceful proportions, giving a more slender and elegant profile than the Doric order. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius compared the Doric module to a sturdy, male body, while the Ionic was possessed of more graceful, feminine proportions. The Ionic order incorporates a running frieze of continuous sculptural relief, as opposed to the Doric frieze composed of triglyphs and metopes.

The Corinthian order

The Corinthian order is both the latest and the most elaborate of the Classical orders of architecture. The order was employed in both Greek and Roman architecture, with minor variations, and gave rise, in turn, to the Composite order. As the name suggests, the origins of the order were connected in antiquity with the Greek city-state of Corinth where, according to the architectural writer Vitruvius, the sculptor Callimachus drew a set of acanthus leaves surrounding a votive basket (Vitr. 4.1.9-10). In archaeological terms the earliest known Corinthian

capital comes from the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae and dates to c. 427 B.C.E.

The defining element of the Corinthian order is its elaborate, carved capital, which incorporates even more vegetal elements than the Ionic order does. The stylized, carved leaves of an acanthus plant grow around the capital, generally terminating just below the abacus. The Romans favored the Corinthian order, perhaps due to its slender properties. The order is employed in numerous notable Roman architectural monuments, including the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Pantheon in Rome, and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

Legacy of the Greek architectural canon

The canonical Greek architectural orders have exerted influence on architects and their imaginations for thousands of years. While Greek architecture played a key role in inspiring the Romans, its legacy also stretches far beyond antiquity. When James “Athenian” Stuart and Nicholas Revett visited Greece during the period from 1748 to 1755 and subsequently published The Antiquities of Athens and Other Monuments of Greece (1762) in London, the Neoclassical revolution was underway. Captivated by Stuart and Revett’s measured drawings and engravings, Europe suddenly demanded Greek forms. Architects the likes of Robert Adam drove the Neoclassical movement, creating buildings like Kedleston Hall, an English country house in Kedleston, Derbyshire. Neoclassicism even jumped the Atlantic Ocean to North America, spreading the rich heritage of Classical architecture even further—and making the Greek architectural orders not only extremely influential, but eternal.

Dipylon Amphora: A Conversation

by Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

As tall as a person, this pot is covered with geometric patterns and early figural representations. This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. To watch the video: youtube.com/watch?v=Uwpdiq9mYME.

Steven: We’re in the National Archeological Museum in Athens looking at the Dipylon Vase.

Beth: The so-called Dipylon Vase because it was found near what would later become the Dipylon Gate in Athens and a cemetery right near there.

Steven: So this is a gigantic, ceramic pot. It’s an anaphora. But it would have been used as a grave marker in antiquity and it’s big. It’s five feet one inch tall.

Beth: Yeah, it’s almost as tall as I am. It’s unusual in that we see figures. We see a narrative scene and this is something that we see emerging more and more in the late geometric period. And geometric is such an obvious name for the style of this vase.

Steven: Well look at the vase, it’s covered from its foot all the way to the lip of its mouth with sharp-edged geometric patterns. I see meanders, I see diamonds, I see triangles. This is a pot coming out of that ancient tradition which really avoided empty space.

Beth: We do see black bands around the base where the neck meets the body and at the very lip of the vase. So we do have some black bands designating the separate parts of the vase.

Steven: But the most interesting part is the fact that we have emerging here representations of animals and even of people. As you said we only see that at the end of the geometric period.

Beth: On the neck of the vase we see deer grazing.

Steven: Below that we see what are either goats or gazelles perhaps or some people have said deer as well.

Beth: Lying down or seated.

Steven: But notice in both cases with the deer and with the goats, it’s really a repeated motif so that it is a continuation of that pattern that is so much a part even of the non-figurative areas of the pot.

Beth: It’s true in the bodies of the animals are reduced to geometric shapes, each one is exactly identical to the one before and the one after and they’re almost easy to miss as animal figures.

Steven: Because they are so much a part of the pattern of the pot.

Beth: Exactly.

Steven: But in the main phrase at the shoulder of the pot, almost at its widest point.

Beth: Right where the handles meet the body.

Steven: We see a number of mourning figures on either side of the body of a dead woman.

Beth: Now we know it’s a woman because she is wearing a skirt and different genders were identified in that way and she’s lying on a funeral bier with a shroud held above her.

Steven: You see figures pulling at their hair, this is a symbol of mourning. Some people have even interpreted the little M-shaped patterns falling between the figures as tears.

Beth: Look at how the artist has avoided leaving any space blank. Even between those M-shapes, he’s painted little star shapes to fill in the blank spaces.

Steven: Below the dead woman we can see perhaps the family. We see larger figures on their knees and then we see smaller figures, perhaps the children.

Beth: The bodies are upside down triangles. The legs are lozenges. Everything is very reduced and the figures are all rendered as black silhouettes. Now the Greeks had a very specific way of firing pots to get the red ground and the black figures above it.

Steven: So this is not glaze in the modern sense, instead this is slipware. So slip is fine particles of clay that are suspended in water and then painted on the surface of the pot. Now this was very difficult because when you painted on that slip it was the same color as the dry clay before it was fired. But then it was the next step that was important.

Beth: It was fired in a kiln at about 900 degrees.

Steven: That’s Celsius.

Beth: It was fired in a way where oxygen was withdrawn from the kiln. This causes the entire pot to turn black.

Steven: The kiln was then allowed to cool somewhat and then oxygen was allowed back into the kiln and then what happens is, the parts of the vase that are not painted return to their warm, red color and only the parts that were painted remain black. And so you can imagine how difficult this was to control in the ancient world before thermometers.

Beth: It really is an amazing testament to the skill of Greek potters.

Steven: Well the person who actually fashioned this pot produced it on a wheel but had to produce it in sections and then fit these sections together seamlessly.

Beth: This is a great example of late geometric Greek pottery.

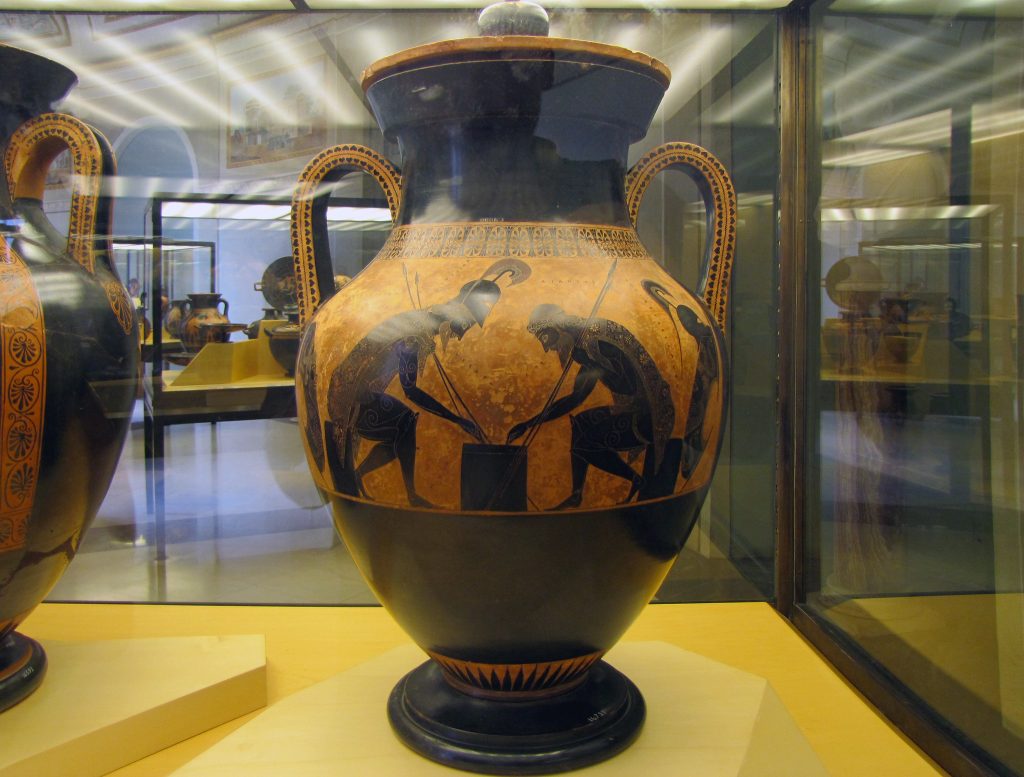

Exekias, Attic Black Figure Amphora with Ajax and Achilles Playing a Game: A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Achilles and Ajax, heroes of the Trojan War, break from battle to play a friendly game that hints at a tragic future. This is a transcript of a conversation conducted at the Etruscan Museum, Vatican, Rome. To watch the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k2fdtepbkz8.

Steven: We’re in the Etruscan Museum in the Vatican Museums in Rome and we’re looking at my favorite pot in the entire world.

Beth: I can see why it’s your favorite pot. It seems to almost glow.

Steven: The thing that makes it so fabulous is we have these two heroes and we have a very simple image, but it’s giving us so much information.

Beth: The heroes are Achilles on the left and Ajax on the right, two of the great Greek heroes featured in Homer’s Iliad and Exekias, the potter, who signed only two pots as the potter and the painter, has identified these two figures by including their names above them, but he’s also telling us what’s happening between the two: Achilles on the left is saying the word “four.”

Steven: You can see “tesara.”Beth: And on the right, we see Ajax, saying “three.”

Steven: “Tri.”

Beth: We know immediately that Achilles is winning the game that they’re playing.

Steven: But this is, of course, a metaphor for the way that this myth will unfold.

Beth: On either side we see their shields. Achilles still has his helmet on, although Ajax has taken his off. So: a moment of relaxation between battles.

Steven: They’re on the battlefield of Troy, but Exekias has given us even more information than this, not simply the rolls of the dice, but in a larger sense, their fate. Look at the way, for example, that while both figures are hunched over and clearly focused on the game at hand–and remember, these two men are really close friends, so there’s an intimacy here, brotherhood—nevertheless, Achilles, who has the higher roll, is holding his spears loosely. You can see the way the points are actually separating. At the bottom, you can see from the lines, they’re not as parallel. But look at the figure on the right, Ajax, whose spears are held in a more parallel way, so that we know that he’s actually clenching with his fist, he’s tense.

Beth: I even sense a little bit of that tension in his brow.

Steven: That’s right. If you look at the brow really closely, you can see that Achilles has a single incised line to represent his eyebrow, but Ajax has a double line and it is a subtle clue that perhaps there’s a little bit of tension there. One other detail that can be easily seen, although it’s really subtle: look at the feet of both figures. Achilles, again, is relaxed. His heel is on the ground line, but Ajax, his heel is picked up ever so slightly, so you can see just a little bit of light underneath it, which means his calf is engaged, those muscles are tense, his body is tense.

Beth: He’s also a little bit more hunched over. His head is a little bit lower than that of his friend Achilles. That does seem to mean something wider than just this board game.

Steven: Anybody who was looking at this pot in the ancient world would have known the story of Ajax and Achilles that Homer tells, as you said, in the Iliad. Achilles is a great hero. In fact, as a child, his mother dipped him in the river Styx, which had the magical quality of making him invincible. It’s just that she held him by his heel, so his heel was not protected and ultimately, he would be killed by an arrow that hits him there.Beth: Hence the term that we use often of someone’s Achilles heel, that is, their vulnerable spot.

Steven: Nevertheless, Achilles will die a great hero. Ajax will have a more complicated fate. He will outlive Achilles, and he will carry his great friend off the battlefield, but ultimately, he’ll be in a battle for Achilles’ armor.

Beth: Achilles had very special armor, which had been made by thegod Hephaestus, the god of the forge.

Steven: Two people would want that armor, and they would both give speeches to convince judges as to who should get the armor, but Ajax, although he was much closer to Achilles, would lose the contest, have a bad moment where he slayed a bunch of Greeks, and ultimately, would kill himself on his own sword. Humiliation at the end of his life.

Beth: It’s really interesting to think about this as an ancient Greek viewer who knows that whole story and what will unfold for both of these heroes, but the story is one thing and the way that Exekias, the potter, has represented this moment and these two figures with so much nobility, with such fine detail in the shape of a vase, which is so elegant, is something else.

Steven: Exekias really was the great master of Attic black-figure vase painting. These are black figures, they are silhouettes. If you look closely, the decorative forms is mostly incised with a needle.

Beth: And the black surface is like paint, but it’s not quite paint.

Steven: This is slipware. Now, the Greeks didn’t have the technology to get kiln ovens hot enough to vitrify, that is to create true glazes, the way ceramics do now. What they would do instead is they would take very fine particles of clay, suspend them in water, and use those as a kind of paint. Depending on the amount of oxygen that they allowed into a kiln, they could turn it black or red. They would paint the surface with this slip and then they would burnish it. That is, they would take a very smooth surface, imagine the back of a spoon, and they would rub it back and forth so you get this surface that is really glossy and it almost looks like glaze.

Beth: When I look closely at the decorative borders on the handles or the decorative border just above the frieze of figures, I can see beautiful detail and the almost three-dimensional form of the slip is almost raised in areas, so it catches the light.

Steven: The Greeks did often use a syringe to paint the finest lines onto the surface, so one could imagine almost decorating a cake. You have a kind of syringe and you have the icing and it leaves a kind of bead that is raised against the surface and at a much finer level, that’s what we’re seeing here.

Beth: So Exekias is a master. His pots stand out in so many ways in their shape, in the painting, in the detail, in the drama that he was able to convey.

Steven: Certainly the Etruscans thought that was the case, because they must have spent a good deal of money importing this pot from Greece, across the Mediterranean, all the way to the Italian peninsula where they lived. So many of the great pots from ancient Greece are actually buried in Etruscan tombs. They were imported. The Greeks did a tremendous business exporting such pots, but Exekias was one of the great masters.

Sculpture in the Archaic Period

Sculpture in the Archaic Period developed rapidly from its early influences, becoming more natural and showing a developing understanding of the body, specifically the musculature and the skin. Close examination of the style’s development allows for precise dating.

Most statues were commissioned as memorials and votive offerings or as grave markers, replacing the vast amphora (two-handled, narrow-necked jars used for wine and oils) and kraters (wide-mouthed vessels) of the previous periods, yet still typically painted in vivid colors.

Kouroi

Kouroi statues (singular, kouros), depicting idealized, nude male youths, were first seen during this period. Carved in the round , often from marble, kouroi are thought to be associated with Apollo; many were found at his shrines and some even depict him. Emulating the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, the figure strides forward on flat feet, arms held stiffly at its side with fists clenched. However, there are some importance differences: kouroi are nude, mostly without identifying attributes and are free-standing.

Early kouroi figures share similarities with Geometric and Orientalizing sculpture, despite their larger scale. For instance, their hair is stylized and patterned, either held back with a headband or under a cap. The New York Kouros strikes a rigid stance and his facial features are blank and expressionless. The body is slightly molded and the musculature is reliant on incised lines .

As kouroi figures developed, they began to lose their Egyptian rigidity and became increasingly naturalistic. The kouros figure of Kroisos, an Athenian youth killed in battle, still depicts a young man with an idealized body. This time though, the body’s form shows realistic modeling.

The muscles of the legs, abdomen, chest and arms appear to actually exist and seem to function and work together. Kroisos’s hair, while still stylized, falls naturally over his neck and onto his back, unlike that of the New York Kouros, which falls down stiffly and in a single sheet. The reddish appearance of his hair reminds the viewer that these sculptures were once painted.

Archaic Smile

Kroisos’s face also appears more naturalistic when compared to the earlier New York Kouros. His cheeks are round and his chin bulbous; however, his smile seems out of place. This is typical of this period and is known as the Archaic smile. It appears to have been added to infuse the sculpture with a sense of being alive and to add a sense of realism.

Kore

A kore (plural korai) sculpture depicts a female youth. Whereas kouroi depict athletic, nude young men, the female korai are fully-clothed, in the idealized image of decorous women. Unlike men—whose bodies were perceived as public, belonging to the state—women’s bodies were deemed private and belonged to their fathers (if unmarried) or husbands.

However, they also have Archaic smiles, with arms either at their sides or with an arm extended, holding an offering. The figures are stiff and retain more block-like characteristics than their male counterparts. Their hair is also stylized, depicted in long strands or braids that cascade down the back or over the shoulder.

The Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) depicts a young woman wearing a peplos, a heavy wool garment that drapes over the whole body, obscuring most of it. A slight indentation between the legs, a division between her torso and legs, and the protrusion of her breasts merely hint at the form of the body underneath.

Remnants of paint on her dress tell us that it was painted yellow with details in blue and red that may have included images of animals. The presence of animals on her dress may indicate that she is the image of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, but she may also just be a nameless maiden.

Later korai figures also show stylistic development, although the bodies are still overshadowed by their clothing. The example of a Kore (520–510 BCE) from the Athenian Acropolis shows a bit more shape in the body, such as defined hips instead of a dramatic belted waistline, although the primary focus of the kore is on the clothing and the drapery. This kore figure wears a chiton (a woolen tunic), a himation (a lightweight undergarment), and a mantle (a cloak). Her facial features are still generic and blank, and she has an Archaic smile. Even with the finer clothes and additional adornments such as jewelry, the figure depicts the idealized Greek female, fully clothed and demure.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Artemis at Corfu

This sculpture, initially designed to fit into the space of the pediment, underwent dramatic changes during the Archaic period, seen later at Aegina. The west pediment at the Temple of Artemis at Corfu depicts not the goddess of the hunt, but the Gorgon Medusa with her children; Pegasus, a winged horse; and Chrysaor, a giant wielding a golden sword surrounded by heraldic lions.

Medusa faces outwards in a challenging position, believed to be apotropaic (warding off evil). Additional scenes include Zeus fighting a Titan, and the slaying of Priam, the king of Troy, by Neoptolemos. These figures are scaled down in order to fit into the shrinking space provided in the pediment.

Pedimental Sculpture: The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina

Sculpted approximately one century later, the pedimental sculptures on the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina gradually grew more naturalistic than their predecessors at Corfu. The dying warrior on the west pediment (c. 490 BCE) is a prime example of Archaic sculpture. The male warrior is depicted nude, with a muscular body that shows the Greeks’ understanding of the musculature of the human body. His hair remains stylized with round, geometric curls and textured patterns.

However, despite the naturalistic characteristics of the body, the body does not seem to react to its environment or circumstances. The warrior props himself up with an arm, and his whole body is tense, despite the fact that he has been struck by an arrow in his chest. His face, with its Archaic smile, and his posture conflict with the reality that he is dying.

Aegina: Transition between Styles

The dying warrior on the east pediment (c. 480 BCE) marks a transition to the new Classical style. Although he bears a slight Archaic smile, this warrior actually reacts to his circumstances. Nearly every part of him appears to be dying.

Instead of propping himself up on an arm, his body responds to the gravity pulling on his dying body, hanging from his shield and attempting to support himself with his other arm. He also attempts to hold himself up with his legs, but one leg has fallen over the pediment’s edge and protrudes into the viewer’s space. His muscles are contracted and limp, depending on which ones they are, and they seem to strain under the weight of the man as he dies.

Statue of a woman (Lady of Auxerre) A CONVERSATION

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/XoEVvoc2PlM

Steven: We’re in the Louvre, in Paris, and we’re looking at a small, free-standing sculpture—a figure that’s often known as the Lady of Auxerre.

Beth: This is a Greek figure, likely from the island of Crete, but she was found, hence her title, in the French city of Auxerre, in the basement of a municipal museum. So we really don’t know about her findspot (the location where the object was originally excavated).

Steven: There’s some conjecture that she may have come originally from a cemetery in Crete, which would mean that she was a funerary sculpture, but we’re not sure. It’s possible that she was a votive figure, that is, a figure that was meant to honor the gods. And some scholars have even suggested that she might be a goddess herself.

Beth: This period, in the seventh century, is referred to as the Daedalic. And that name comes from the legendary sculptor Daedalus, who was said to be from the island of Crete.

Steven: This is a stylistic period that comes before the Archaic and parallels the Orientalizing style in ceramic decoration.

Beth: And in so many ways, she really does seem to prefigure the Archaic figures that we call kore: freestanding female figures that were sometimes representations of goddesses, sometimes votive figures (offerings to the gods)… This columnar (resembling a column) female figure who is very frontally oriented.

Steven: And abstracted. Her head is flattened, the face is relatively flat, the eyes are almond shaped.

Beth: “Flattened” is a good word here, because the front of her body appears flattened–although we do see her breasts—and even her hair has a flattened effect on either side of her face, and the top of her head also seems flattened.

Steven: But these are not unique characteristics to this sculpture. This is consistent with other sculptures of this period and of this area.

Beth: This is carved out of limestone. We’re used to seeing Greek sculptures as white marble, but we now know that these sculptures were generally brightly painted.

Steven: One of the most delicate aspects is the incising (lines cut into the stone). And we can see it most obviously in the square patterns in the front of her dress, but you can also make it out in the wrap that she wears around her shoulders and that move down one side of her arm.

Beth: And you can also make it out in the very wide belt that she wears and even in that collar underneath the shawl. What strikes me is that this is a very idealized figure; this is not meant to be a portrait of the deceased person whose grave this may have marked. This is a figure shown, very much like later Greek figures in the Archaic and Classical period, at the prime of life. She is beautiful, she’s young, she looks strong and healthy. Her waist is very narrow… She’s very feminine.

Steven: And the corners of her mouth are upturned in an expression that is sometimes referred to as the “Archaic smile,” even though this is before the Archaic period. Some art historians have conjectured that this may be an expression of well-being, of happiness, or perhaps a kind of transcendence. She feels so formal. Her feet are together.

Beth: That hand, in front…the other hand, that seems almost glued to the side of her body. But, unlike, earlier Egyptian figures, she’s freed from the stone. We have space between her body and her arms, which is an important part of this very early Greek tradition, which we’ll see in Archaic Greek art. And despite all the abstraction in her body that we just talked about, there’s something very lifelike about her, especially in her face. And I think that would have been even more true when she was painted; if we imagine the pink of her lips, or painted pupils in her eyes, or her hair painted brown…

Steven: One of the reasons that a figure like this fascinates art historians is because we know what happens next. She stands at the beginning of this long history of Greek sculpture, which reaches levels of brilliance that we’ve admired for thousands of years after. We’re seeing an early figure here, but one that, with all of the hindsight that we have, offers extraordinary promise.

The Greek Early Classical Period

Architecture & Sculpture

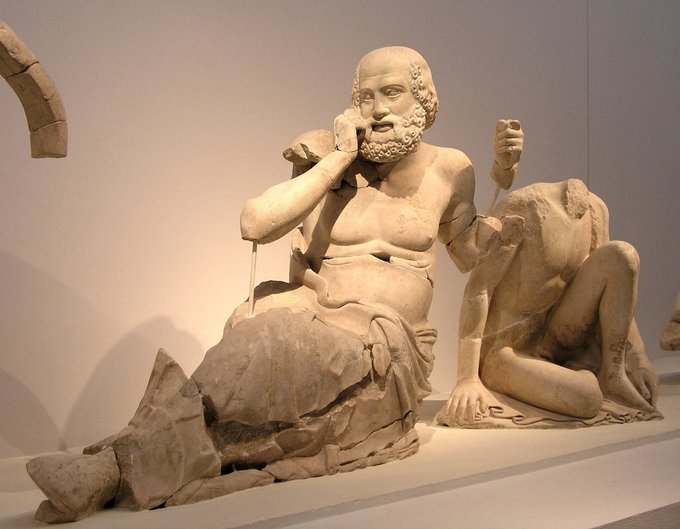

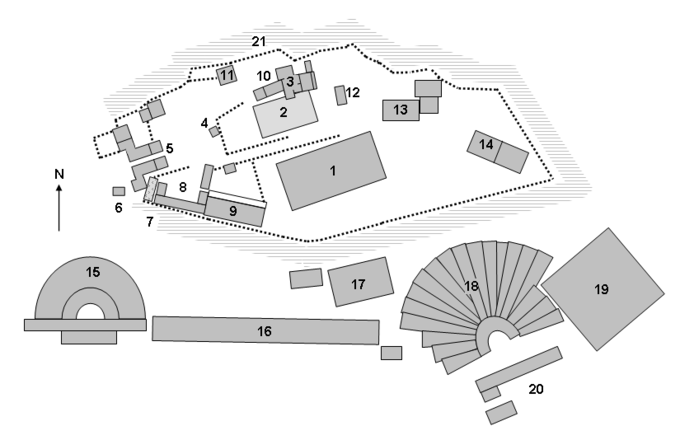

Temple of Zeus at Olympia

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia is a colossal ruined temple in the center of the Greek capital Athens that was dedicated to Zeus, king of the Olympian gods. Its plan is similar to that of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina.

It is hexastyle, with six columns across the front and back and 13 down each side. It has two columns directly connected to the walls of the temple, known as in antis, in front of both the entranceway (pronaos ) and the inner shrine ( opisthodomos ). Like the Temple of Aphaia, there are two, two-story colonnades of seven columns on each side of the inner sanctuary (naos).The pedimental figures are depicted in the developing Classical style with naturalistic yet overly muscular bodies. Most of the figures are shown with the expressionless faces of the Severe style.

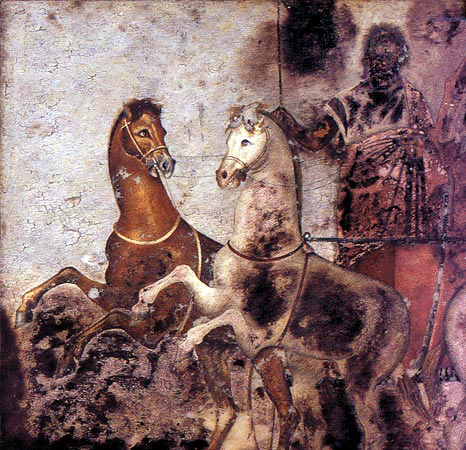

The figures on the east pediment await the start of a chariot race, and the whole composition is still and static . A seer, however, watches it in horror as he foresees the death of Oenomaus. This level of emotion would never be present in Archaic statues and it breaks the Early Classical Severe style, allowing the viewer to sense the forbidding events about to happen. The level of emotion on the seer’s face would never be present in Archaic statues and it breaks the Early Classical Severe style, allowing the viewer to sense the forbidding events about to happen.

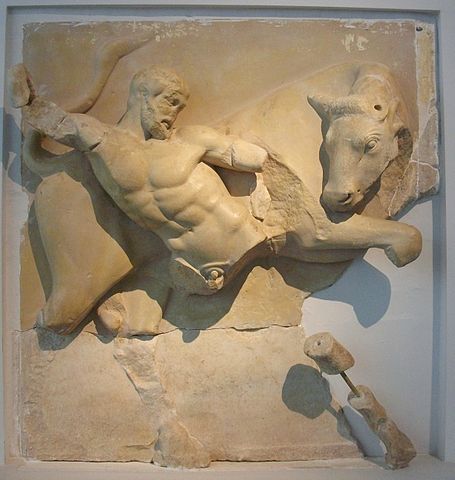

Unlike the static composition of the eastern pediment, the Centauromachy (below) on the western pediment depicts movement that radiates out from its center. The centaurs, fighting men, and abducted women struggle and fight against each other, creating tension in another example of an early portrayal of emotion. Most figures are depicted in the Severe style. However, some, including a centaur, have facial features that reflect their wrath and anger.

The twelve metopes over the pronaos and opisthodomos depict scenes from the twelve labors of Herakles. Like the development in pedimental sculpture, the reliefs on the metopes display the Early Classical understanding of the body. Herakles’ body is strong and idealized, yet it has a level of naturalism and plasticity that increases the liveliness of the reliefs.

The scenes depict varying types of compositions. Some are static with two or three figures standing rigidly, while others, such as Herakles and the Cretan Bull, convey a sense of liveliness through their diagonal composition and overlapping bodies.

Kritios Boy

A slightly smaller-than-life statue known as the Kritios Boy was dedicated to Athena by an athlete and found in the Perserchutt of the Athenian Acropolis. Its title derives from a famous artist to whom the sculpture was once attributed.

The marble statue is a prime example of the Early Classical sculptural style and demonstrates the shift away from the stiff style seen in Archaic kouroi. The torso depicts an understanding of the body and plasticity of the muscles and skin that allows the statue to come to life.

Part of this illusion is created by a stance known as contrapposto. This describes a person with his or her weight shifted onto one leg, which creates a shift in the hips, chest, and shoulders to create a stance that is more dramatic and naturalistic than a stiff, frontal pose. This contrapposto position animates the figure through the relationship of tense and relaxed limbs.

However, the face of the Kritios Boy is expressionless, which contradicts the naturalism seen in his body. This is known as the Severe style. The blank expressions allow the sculpture to appear less naturalistic, which creates a screen between the art and the viewer. This differs from the use of the Archaic smile (now gone), which was added to sculpture to increase their naturalism. However, the now empty eye sockets once held inlaid stone to give the sculpture a lifelike appearance.

Kritios Boy: A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Acropolis in Athens. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/Q5IWDhXtsmE

Steven: We’re in the new Acropolis museum, in Athens, looking at the Kritios Boy.

Beth: We’re in the very late archaic period. Some call this the severe style. We might even call this early classical.

Steven: It’s really this transition between the late archaic and the early classical. The sculpture is such a great embodiment of that.

Beth: It allows us to see the transition between the archaic kouros, and the much more naturalistic, movement-filled figures that we find on the Parthenon, for example, on the frieze or in the metopes.

Steven: This sculpture was probably broken originally when the Persians invaded Athens and desecrated the Acropolis. This was a huge blow to the Greeks, and when they finally recovered this territory, they took the sculptures that had been destroyed, and they buried them. So it’s ironic that the reason that these sculptures are preserved is in part because they were destroyed, but to make the story even more complicated, before the Greeks had been defeated by the Persians, they had an earlier victory at Marathon.

Beth: Where an overwhelming force of Persians was defeated.

Steven: That first victory by the Greeks, over the Persians, is important to understand, in relationship to the sculpture, because some art historians have suggested that the new-found naturalism that we see in the sculpture is a result of the new sense of self; the new sense of self-determination, that came in the wake of the victory over the Persians.

Beth: And a sense of Athens as the leader among the Greek city-states, who united against the Persians.

Steven: So like the earlier kouros figures, this is marble; it’s a standing nude; he’s relatively still, although there is this potential for movement.

Beth: With the kouros figures, we had a figure that was both standing still and moving simultaneously, but we have incipient movement. Movement about to take place. We have a sense of process, and I think it’s that unfolding of time, that makes this figure seem so much a part of our world, instead of the timeless world of the kouros.

Steven: The kouros figures were depicted as stick figures. There were mechanical joints, that were suggested, but did not really exist.

Beth: Didn’t really work.

Steven: That’s right. There was no way for those figures to actually move, whereas this figure, the much more naturalistic renderings of the volumes of the body; the understanding of the musculature; the understanding of the bone structure; and especially the transitions from one part of the body to the next, make the potential for movement believable.

Beth: Although we don’t see the feet, and the right side, we don’t see the calf, there is a sense that this figure is standing in a pose that art historians call contrapposto. That is, his weight is shifted onto one leg, and here’s the important part; as a result, other things happen within the body, so that one shift in one part of the body affects the rest of the body, so the body acts in unison.

Steven: We can see that very clearly with the knees. The weight-bearing knee is higher than the free-leg knee, and that’s because that knee droops down a little bit. The axis of the hips are no longer aligned. The weight-bearing leg has a hip that juts upward, into the torso, where the free leg, the hip hands down.

Beth: The shoulder above the weight-bearing leg actually drops down slightly, and that compresses the torso in between. His lifelikeness is carried into the head, which shifts a little bit, so we don’t have that strict frontality that we saw in the kouroi. The symmetry of the body is broken. In actuality human beings are never symmetrical, right? Our bodies move and shift.

Steven: That’s why the kouroi seem so artificial.

Beth: Exactly; they seem transcendent and timeless, but because the Kritios Boy is asymmetrical, we have a sense of his engagement with the world. Gone is that archaic smile, that seems to transcend reality, but one of the really interesting things about the Kritios Boy is, if we look from the side, we see an arch in his back, and there’s a sense that he’s moving forward, and holding himself back at the same time. He’s a bit of a tease.

Steven: He’s in a very relaxed pose.

Beth: We should mention that the Greeks had started to make bronze sculptures just before this, and bronze allowed artists to create sculptures with limbs more separated from the torso, or limbs lifted into space.

Steven: And you can see why that could be tricky in marble. In fact this figure has lost its leg, and it’s lost its arms. On his left hip you can still see a fragment of the strut or bridge that would have helped support the arm that would have been next to it. That also lets us know that the arm really was at his sides, very much like a traditional kouros.

Beth: We see the desire on the part of the Greeks, on the part of this artist, to create a sculpture that’s more open, where the limbs and the torso are more separated from one another, but in marble that’s really hard to do.

Steven: One more point about the interest in bronze. Unlike so much marble sculpture, here we have eyes that have been hollowed out. They would have been inset, probably, with glass paste eyes, that would have been very lifelike, and that’s a technique that was commonly used in bronze. In traditional marble sculptures, you actually have the eye as part of the solid piece of marble, and they would have just been painted. There is this interesting reference to the technique of bronze casting, even here in a marble sculpture, and I should mention that the reason we call the Kritios Boy is because the Kritios sculptor was an important sculptor in bronze at this time, of which this is very stylistically similar.

In the entire body, we’ve moved away from the linear representation of symbols of the body, and we now have these smooth, beautiful, volumes, that represent this Greek ideal of the athletic male youth.

Beth: That represented the peak of human achievement, and also the qualities of the divine.

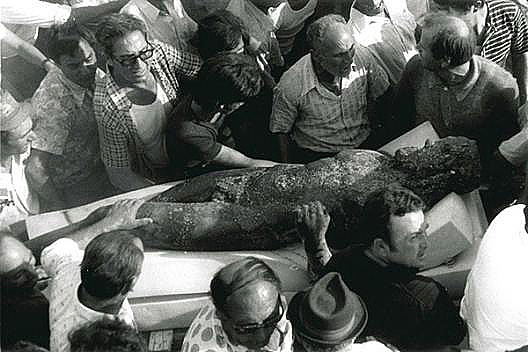

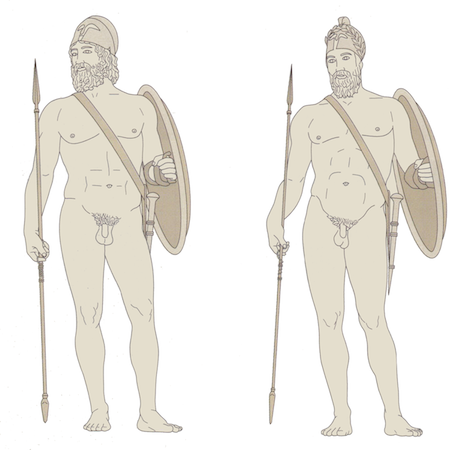

Riace Warriors

The Riace Warriors (also referred to as the Riace bronzes or Bronzi di Riace) are two life-size Greek bronze statues of naked, bearded warriors. The statues were discovered by Stefano Mariottini in the Mediterranean Sea just off the coast of Riace Marina, Italy, on August 16, 1972. The statues are currently housed in the Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia in the Italian city of Reggio Calabria. The statues are commonly referred to as “Statue A” and “Statue B” and were originally cast using the lost-wax technique.

Statue A

Statue A stands 198 centimeters tall and depicts the younger of the two warriors. His body exhibits a strong contrapposto stance, with the head turned to his right. Attached elements have been lost – most likely a shield and a spear; his now-lost helmet atop his head may have been crowned by a wreath. The warrior is bearded, with applied copper detail for the lips and the nipples. Inset eyes also survive for

Statue A. The hair and beard have been worked in an elaborate fashion, with exquisite curls and ringlets.

Statue B

Statue B depicts an older warrior and stands 197 centimeters tall. A now-missing helmet likely was perched atop his head. Like Statue A, Statue B is bearded and in a contrapposto stance, although the feet of Statue B and set more closely together than those of Statue A.

Severe style

The Severe or Early Classical style describes the trends in Greek sculpture between c. 490 and 450 B.C.E. Artistically this stylistic phase represents a transition from the rather austere and static Archaic style of the sixth century B.C.E. to the more idealized Classical style. The Severe style is marked by an increased interest in the use of bronze as a medium as well as an increase in the characterization of the sculpture, among other features.

Interpretation and chronology

The chronology of the Riace warriors has been a matter of scholarly contention since their discovery. In essence there are two schools of thought—one holds that the warriors are fifth century B.C.E. originals that were created between 460 and 420 B.C.E., while another holds that the statues were produced later and consciously imitate Early Classical sculpture. Those that support the earlier chronology argue that Statue A is the earlier of the two pieces. Those scholars also make a connection between the warriors and the workshops of famous ancient sculptors. For instance, some scholars suggest that the sculptor Myron crafted Statue A, while Alkamenes created Statue B. Additionally, those who support the earlier chronology point to the Severe Style as a clear indication of an Early Classical date for these two masterpieces.

The art historian B. S. Ridgway presents a dissenting view, contending that the statues should not be assigned to the fifth century B.C.E., arguing instead that they were most likely produced together after 100 B.C.E. Ridgway feels that the statues indicate an interest in Early Classical iconography during the Hellenistic period.

In terms of identifications, there has been speculation that the two statues represent Tydeus (Statue A) and Amphiaraus (Statue B), two warriors from Aeschylus’ tragic play, Seven Against Thebes (about Polyneices after the fall of his father, King Oedipus), and may have been part of a monumental sculptural composition. A group from Argos described by Pausanias (the Greek traveler and writer) is often cited in connection to this conjecture: “A little farther on is a sanctuary of the Seasons. On coming back from here you see statues of Polyneices, the son of Oedipus, and of all the chieftains who with him were killed in battle at the wall of Thebes…” (Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.20.5).

The statues have lead dowels installed in their feet, indicating that they were originally mounted on a base and installed as part of some sculptural group or other. The art historian Carol Mattusch argues that not only were they found together, but that they were originally installed—and perhaps produced—together in antiquity.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

For the ancient Greeks, the human body was perfect. Explore this example of the mathematical source of ideal beauty.

Roman copies of ancient Greek art

When we study ancient Greek art, so often we are really looking at ancient Roman art, or at least their copies of ancient Greek sculpture (or paintings and architecture for that matter).

Basically, just about every Roman wanted ancient Greek art. For the Romans, Greek culture symbolized a desirable way of life—of leisure, the arts, luxury and learning.

The popularity of ancient Greek art for the Romans

Greek art became the rage when Roman generals began conquering Greek cities (beginning in 211 B.C.E.), and returned triumphantly to Rome not with the usual booty of gold and silver coins, but with works of art. This work so impressed the Roman elite that studios were set up to meet the growing demand for copies destined for the villas of wealthy Romans. The Doryphoros was one of the most sought after, and most copied, Greek sculptures.

Bronze versus marble

For the most part, the Greeks created their free-standing sculpture in bronze, but because bronze is valuable and can be melted down and reused, sculpture was often recast into weapons. This is why so few ancient Greek bronze originals survive, and why we often have to look at ancient Roman copies in marble (of varying quality) to try to understand what the Greeks achieved.

Why sculptures are often incomplete or reconstructed

To make matter worse, Roman marble sculptures were buried for centuries, and very often we recover only fragments of a sculpture that have to be reassembled. This is the reason you will often see that sculptures in museums include an arm or hand that are modern recreations, or that ancient sculptures are simply displayed incomplete.

The Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) in the Naples museum (image above) is a Roman copy of a lost Greek original that we think was found, largely intact, in the provincial Roman city of Pompeii.1

The canon

The idea of a canon, a rule for a standard of beauty developed for artists to follow, was not new to the ancient Greeks. The ancient Egyptians also developed a canon. Centuries later, during the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci investigated the ideal proportions of the human body with his Vitruvian Man.

Polykleitos’s idea of relating beauty to ratio was later summarized by Galen, writing in the second century,

Beauty consists in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other.

To watch Dr. Beth Harris & Dr. Steven Zucker discuss the Doryphoros: https://youtu.be/EAR9RAMg9NY

The Athenian Acropolis

The study of Classical-era architecture is dominated by the study of the construction of the Athenian Acropolis and the development of the Athenian agora. The Acropolis is an ancient citadel located on a high, rocky outcrop above and at the center of the city of Athens. It contains the remains of several ancient buildings of great architectural and historic significance.

The word acropolis comes from the Greek words άκρο (akron, meaning edge or extremity) and πόλη (polis, meaning city). Although there are many other acropolises in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification.

The Acropolis has played a significant role in the city from the time that the area was first inhabited during the Neolithic era. While there is evidence that the hill was inhabited as far back as the fourth millennium BCE, in the High Classical Period it was Pericles (c. 495–429 BCE) who coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings, including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the temple of Athena Nike.

The buildings on the Acropolis were constructed in the Doric and Ionic orders, with dramatic reliefs adorning many of their pediments, friezes, and metopes.

In recent centuries, its architecture has influenced the design of many public buildings in the Western hemisphere.

Early History

Archaeological evidence shows that the acropolis was once home to a Mycenaean citadel. The citadel’s Cyclopean walls defended the Acropolis for centuries, and still remains today. The Acropolis was continually inhabited, even through the Greek Dark Ages when Mycenaean civilization fell.

It is during the Geometric period that the Acropolis shifted from being the home of a king to being a sanctuary site dedicated to the goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. The Archaic -era Acropolis saw the first stone temple dedicated to Athena, known as the Hekatompedon (Greek for hundred-footed).

This building was built from limestone around 570 to 550 BCE and was a hundred feet long. It has the original home of the olive-wood statue of Athena Polias, known as the Palladium, that was believed to have come from Troy.

In the early fifth century the Persians invaded Greece, and the city of Athens—along with the Acropolis—was destroyed, looted, and burnt to the ground in 480 BCE. Later the Athenians, before the final battle at Plataea, swore an oath that if they won the battle—that if Athena once more protected her city—then the Athenian citizens would leave the Acropolis as it is, destroyed, as a monument to the war. The Athenians did indeed win the war, and the Acropolis was left in ruins for thirty years.

Periclean Revival

It was immediately following the Persian war that the Athenian general and statesman Pericles funded an extensive building program on the Athenian Acropolis. Despite the vow to leave the Acropolis in a state of ruin, the site was rebuilt, incorporating all the remaining old materials into the spaces of the new site.

The building program began in 447 BCE and was completed by 415 BCE. It employed the most famous architects and artists of the age and its sculpture and buildings were designed to complement and be in dialog with one another.

The Propylaea

Mnesicles designed the Propylaea (437–432 BCE), the monumental gateway to the Acropolis. It funneled all traffic to the Acropolis onto one gently sloped ramp. The Propylaea created a massive screen wall that was impressive and protective as well as welcoming.

It was designed to appear symmetrical but, in reality, was not. This illusion was created by a colonnade of paired columns that wrapped around the gateway. The southern wing incorporated the original Cyclopean walls from the Mycenaean citadel. This space was truncated but served as dining area for feasting after a sacrifice.

The northern wing was much larger. It was a pinacoteca , where large panel paintings were hung for public viewing. The order of the Propylaea and its columns are Doric, and its decoration is simple—there are no reliefs in the metopes and pediment.

Upon entering the Acropolis from the Propylaea, visitors were greeted by a colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos (c. 456 BCE), designed by Phidias. Accounts and a few coins minted with images of the statue allow us to conclude that the bronze statue portrayed a fearsome image of a helmeted Athena striding forward, with her shield at her side and her spear raised high, ready to strike.

The Erechtheion

The Erechtheion (421–406 BCE), designed by Mnesicles, is an ancient Greek temple on the north side of the Acropolis. Scholars believe the temple was built in honor of the legendary king Erechtheus.It was built on the site of the Hekatompedon and over the megaron of the Mycenaean citadel. The odd design of the temple results from the site’s topography and the temple’s incorporation of numerous ancient sites.

The temple housed the Palladium, the ancient olive-wood statue of Athena. It was also believed to be the site of the contest between Athena and Poseidon, and so displayed an olive tree, a salt-water well, and the marks from Poseidon’s trident to the faithful.

Shrines to the mythical kings of Athens, Cecrops and Erechteus—who gives the temple its name—were also found within the Erechtheion. Because of its mythic significance and its religious relics, the Erechtheion was the ending site of the Panathenaic festival, when the peplos on the olive-wood statue of Athena was annually replaced with new clothing with due pomp and ritual.

A porch on the south side of the Erechtheion is known as the Porch of the Caryatids, or the Porch of the Maidens. Six, towering, sculpted women (caryatids) support the entablature. The women replace the columns, yet look columnar themselves. Their drapery, especially over their weight-bearing leg, is long and linear, creating a parallel to the fluting on an Ionic column.

Although they stand in similar poses, each statue has its own stance, facial features, hair, and drapery. They carry egg-and-dart capitals on their heads, much as women throughout history have carried baskets. Between their heads and this capital is a sculpted cushion, which gives the appearance of softening the load of the weight of the building.

The sculpted columnar form of the caryatids is named after the women of the town of Kayrai, a small town near and allied to Sparta. At one point during the Persian Wars the town betrayed Athens to the Persians. In retaliation, the Athenians sacked their city, killing the men and enslaving the women and children. Thus, the caryatids depicted on the Acropolis are symbolic representations of the full power of Athenian authority over Greece and the punishment of traitors.

The Temple of Athena Nike

The Temple of Athena Nike (427–425 BCE), designed by Kallikrates in honor of the goddess of victory, stands on the parapet of the Acropolis, to the southwest and to the right of the Propylaea. The temple is a small Ionic temple that consists of a single naos, where a cult statue stood fronted by four piers. The four piers aligned to the four Ionic prostyle columns of the pronaos. Both the pronaos and opisthodomos are very small, nearly non-existent, and are defined by their four prostyle columns.

The continuous frieze around the temple depicts battle scenes from Greek history. These representations include battles from the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, including a cavalry scene from the Battle at Marathon and the Greek victory over the Persians at the Battle of Plataea.

The scenes on the Temple of Athena Nike are similar to the battle scenes on the Parthenon, which represented Greek dominance over non-Greeks and foreigners in mythical allegory . The scenes depicted on the frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike frieze display Greek and Athenian dominance and military power throughout historical events.

A parapet was added on the balustrade to protect visitors from falling down the steep hillside. Images of Nike, such as Nike Adjusting Her Sandal, are carved in relief.

In this scene Nike is portrayed standing on one leg as she bends over a raised foot and knee to adjust her sandal. Her body is depicted in the new High Classical style. Unlike Archaic sculpture, this scene actually depicts Nike’s body. Her body and muscles are clearly distinguished underneath her transparent yet heavy clothing.

This style, known as wet drapery, allows sculptors to depict the body of a woman while still preserving the modesty of the female figure. Although Nike’s body is visible, she remains fully clothed. This style is found elsewhere on the Acropolis, such as on the caryatids and on the women in the Parthenon’s pediment.

The Parthenon, Athens: A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Learn about the great temple of Athena, patron of Athens, and the building’s troubled history. This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Acropolis in Athens. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/tWDflkBZC6U.

Steven: We’re looking at the Parthenon. This is a huge marble temple to the goddess Athena.

Beth: We’re on the top of a rocky outcropping in the city of Athens very high up overlooking the city, overlooking the Aegean Sea.

Steven: Athens was just one of many Greek city-states and almost everyone had an acropolis. That is, had a fortified hill within its city because these were warring states.

Beth: In the fifth century, Athens was the most powerful city-state and that’s the period that the Parthenon dates to.

Steven: This precinct became a sacred one rather than a defensive one. This building has had a tremendous influence not only because it becomes the symbol of the birth of democracy, but also because of its extraordinary architectural refinement. The period when this was built in the fifth century is considered the High Classical moment and for so much of Western history, we have measured our later achievements against this perfection.

Beth: It’s hard not to recognize so many buildings in the West. There’s certainly an association especially to buildings in Washington D.C. and that’s not a coincidence.

Steven: Because this is the birthplace of democracy—a limited democracy, but democracy nevertheless.

Beth: There was a series of reforms in the fifth century in Athens that allowed more and more people to participate in the government.

Steven: We think that the city of Athens had between 300,000 and 400,000 inhabitants, and only about 50,000 were actually considered citizens. If you were a woman, obviously, if you were a slave you were not participating in this democratic experiment.

Beth: This is a very limited idea of democracy.

Steven: This building is dedicated to Athena and, in fact, the city itself is named after her and of course there’s a myth. Two gods vying for the honor of being the patron of this city. Those two gods are Poseidon and Athena. Poseidon is the god of the sea and Athena has many aspects. She’s the goddess of wisdom, she is associated with war. A kind of intelligence about creating and making things. Both of these gods gave the people of this city a gift and then they had to choose. Poseidon strikes a rock and from it springs forth the saltwater of the sea. This had to do with the gift of naval superiority.

Beth: Athena offered, in contrast, an olive tree. The idea of the land of prosperity, of peace. The Athenians chose Athena’s gift. There actually is a site here on the acropolis where the Athenians believed you could see the mark of the trident from Poseidon where he struck the ground and also the tree that Athena offered.

Steven: Actually the modern Greeks have replanted an olive tree in that space. Let’s talk about the building. It is really what we think of when we think of a Greek temple but the style is specific. This is a Doric temple.

Beth: Although it has Ionic elements which we’ll get to.

Steven: The Doric features are really easy to identify. You have massive columns with shallow broad flutes, the vertical lines. Those columns go down directly into the floor of the temple which is called the stylobate and at the top, the capitals are very simple. There’s a little flare that rises up to a simple rectangular block called an abacus. Just above that are triglyphs and metopes.

Beth: It’s important to say that this building was covered with sculpture. There was sculpture in the metopes, there was sculpture in the pediments and in an unprecedented way a frieze that ran all the way around four sides of the building just inside this outer row of columns that we see. Now, this is an Ionic feature. Art historians talk about how this building combines Doric elements with Ionic elements.

Steven: In fact, there were four Ionic columns inside the west end of the temple.

Beth: When the citizens of Athens walked up the sacred way perhaps for religious procession or festival. They encountered the west end and they walked around it either on the north or south sides to the east and the entrance. Right above the entrance in the sculptures of the pediment, they could see the story of Athena and Poseidon vying to be the patron of the city of Athens. On the frieze just inside they saw themselves perhaps at least in one interpretation involved in the Panathenaic Procession, the religious procession in honor of the goddess Athena. This was a building that you walked up to, you walked around and inside was this gigantic sculpture of Athena.

Steven: These were all sculptures that we believe were overseen by the great sculptor Phidias and one of my favorite parts are the metopes. Carved with scenes that showed the Greeks battling various enemies either directly or metaphorically. The Greeks battling the Amazons, the Greeks against the Trojans, the Lapiths against the Centaurs, and the Gigantomachy. The Greek gods against the Titans.

Beth: All of these battles signified the ascendancy of Greece and of the Athenians of their triumphs. Civilization over barbarism, rational thought over chaos.

Steven: You’ve just hit on the very meaning of this building. This is not the first temple to Athena on this site. Just a little bit to the right as we look at the east end there was an older temple to Athena that was destroyed when the Persians invaded. This was a devastating blow to the Athenians.

Beth: One really can’t overstate the importance of the Persian War for the Athenian mindset that created the Parthenon. Athens was invaded and beyond that, the Persians sacked the Acropolis, sacked the sacred site, the temples. Destroyed the buildings.

Steven: They burned them down. In fact, the Athenians took a vow that they would never remove the ruins of the old temple to Athena.

Beth: So they would remember it forever.

Steven: But a generation later they did.

Beth: They did, well there was a piece that was established with the Persians and some historians think that that allowed them to renege that vow and Pericles, the leader of Athens embarked on this enormous, very expensive building campaign.

Steven: Historians believe that he was able to fund that because the Athenians had become the leaders of what is called the Delian League. An association of Greek city-states that paid a kind of tax to help protect Greece against Persia but Pericles dipped into that treasury and built this building.

Beth: This alliance of Greek city-states, their treasure, their tax money, their tribute was originally located in Delos hence the Delian League, but Pericles managed to have that treasure moved here to Athens and actually housed in the Acropolis. The sculpture of Athena herself which was made of gold and ivory Phidias said if we need money we can melt down the enormous amount of gold that decorates this sculpture of Athena.

Steven: Since that sculpture doesn’t exist any longer we know somebody did that. We need to imagine this building not pristine and white but rather brightly colored and also a building that was used. This was a storehouse. It was the treasury and so we have to imagine that it was absolutely full of valuable stuff.

Beth: In fact, we have records that give us some idea of what was stored here. We think about temples or churches or mosques as places where you go in to worship. That’s not how Greek religion work. There usually was an altar on the outside where sacrifices were made and the temple was the house of the god or goddess, but with the Parthenon art historians and archeologists have not been able to locate an altar outside so we’ve wondered what was this building? One answer is it was a treasury.

Steven: It also functions symbolically. It is up on this hill. It commands this extraordinary view from all parts of the city, and so it was a symbol of both the city’s wealth and power.

Beth: It’s a gift to Athena. When you make a gift to your patron goddess you want visitors to be awed by the image of the goddess that was inside and of her home.

Steven: This isn’t any goddess. This is the goddess of wisdom so the ability of man to understand our world and its rules mathematically, and then to express them in a structure like this is absolutely appropriate.

Beth: Iktinos is a supreme mathematician. I mean we know that the Greeks even in the archaic period before this were concerned with ideal proportions.

Steven: Pythagoras.

Beth: Or the sculptor Polykleitos and his sculpture of the Doryphoros searching for perfect proportions and harmony and using mathematics as the basis for thinking that through.

Steven: We have that here.

Beth: To an unbelievable degree.

Steven: What’s extraordinary is that its perfection is an illusion based on a series of subtle distortions that actually correct for the imperfections of our sight. That is, the Greeks recognize that human perception was itself yawed and that they needed to adjust for it in order to give the visual impression of perfection. Their mathematics and their building skills were precise enough to be able to pull this off.

Beth: Every stone was cut to fit precisely.

Steven: When we look at this building we assume it’s rectilinear, it’s full of right angles, and in fact, there’s hardly a right angle in this building.

Beth: There’s another interpretation of these tiny deviations that these deviations give the building a sense of dynamism. The sense of the organic that otherwise, it would seem static and lifeless. The Greeks had used this idea that art historians call entasis before in other buildings- slight adjustments. For example, columns bulge toward the center. This is not new but the degree to which it’s used here and the subtlety in the way it’s used is unprecedented.

Steven: For instance, in those Doric columns you can see that there’s a taper and you assume that it’s a straight line but the Greeks wanted ever so slight a sense of the organic. That the weight of the building was being expressed in the bulge, the entasis of the column about a third of the way from the bosom. In this case, every single column bulges only 11/16th of an inch the entire length of that column. The way that the Greeks pulled this off is they would bring column drums up to the site. They would carefully carve the base and the top and then they would carve in between.

Beth: We see this slight deviation in the columns but we also see it not only vertically but also horizontally in the building.

Steven: That’s right. You assume that the stylobate, the floor of the temple, is flat but it’s not. Rainwater would run off it because the edges are lower than the center.

Beth: But only very, very slightly lower.

Steven: Across the long side of the temple the center rises only 4 3/8 of an inch and on the short side of the temple on the east and the west side the center rises only by 2 3/8 inches. What happens is it cracks. Our eye would naturally see a straight line seem as if it rises up at the corners a little bit so it seems to us to be perfectly flat. The columns are all leaning in a little bit.

Beth: You would expect the columns to be equidistant from one another but in fact, the columns on the edges are slightly closer to one another than the columns in the center of each side.

Steven: Architectural historians have hypothesized that the reason for this is because the column at the edge is in the sense an orphan. It doesn’t have anything past it. Therefore, it would seem to be less substantial. If we could make that column a little bit closer to the one next to it it might compensate and it would have an even sense of density across the building.

Beth: Placing of the columns closer together on the edges create a problem in the levels above. One of the rules of the Doric Order is that there had to be a triglyph right above the center of a column or in between each column.

Steven: They also wanted the triglyphs to be at the very edge so one triglyph would abut against another triglyph at the corner of the building. If in fact, you’re placing your columns closer together you can actually solve for that problem, you can avoid the stretch of the metope in between those triglyphs that would result, but because the columns are placed so close together they had the opposite problem which is to say that the metopes at the ends of the building would be too slender. What Phidias has done in concert with Iktinos and Kallikrates the architects is to create sculptural metopes that are widest in the center just like the spaces between the columns and actually the metopes themselves gradually become thinner as you move to the edges so that you can’t really even perceive the change without measuring.

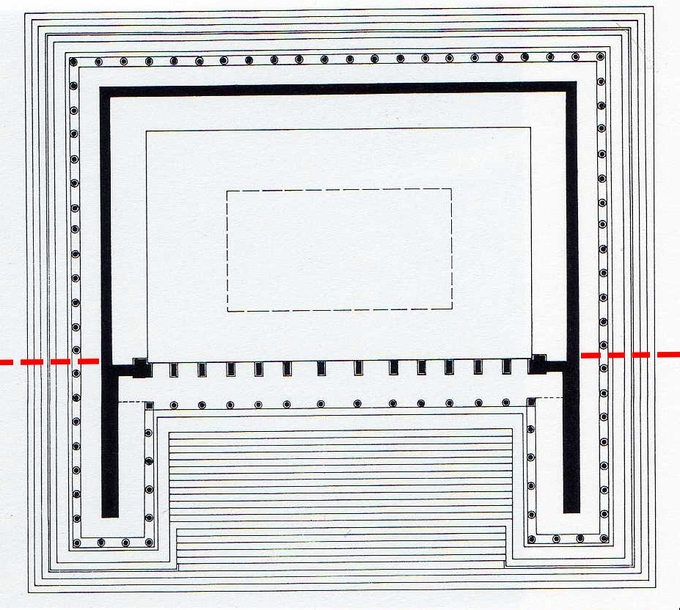

Beth: The general proportions of the building can be expressed mathematically as X = Y x 2 + 1. Across the front, we see eight columns and along the sides 17 columns. That ratio also governs the spacing between the columns and its relationship to the diameter of a column. Math is everywhere.

Steven: If we look at the plan of the structure we see the exterior colonnade on all four sides. On the east and west end, it’s actually a double colonnade and on the long sides, inside the columns a solid a solid masonry wall. You can enter rooms on the east-west only. The west has a smaller room with the four Ionic columns within it but the east room was larger and held the monumental sculpture of Athena. It’s interesting. The system that was used to create a vault that was high enough to enclose a sculpture that was almost 40 feet high was unique. There was a U shape of interior columns at two storeys. They were Doric and they surrounded the goddess. The sculpture is now lost but the building is almost lost as well. Here we come to one of the great tragedies of western architecture. This building survived into the seventeenth century and was in pretty good shape for 2000 years and it’s only in the modern era that it became a ruin.