Origins and the life of Muhammad the Prophet

Islam, Judaism and Christianity are three of the world’s great monotheistic faiths. They share many of the same holy sites, such as Jerusalem, and prophets, such as Abraham. Collectively, scholars refer to these three religions as the Abrahamic faiths, since Abraham and his family played vital roles in the formation of these religions.

Islam was founded by Muhammad (c. 570-632 C.E.), a merchant from the city of Mecca, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Mecca was a well-established trading city. The Kaaba (in Mecca) is the focus of pilgrimage for Muslims.

The Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, provides very little detail about Muhammad’s life; however, the hadiths, or sayings of the Prophet, which were largely compiled in the centuries following Muhammad’s death, provide a larger narrative for the events in his life. Muhammad was born in 570 C.E. in Mecca, and his early life was unremarkable. He married a wealthy widow named Khadija. Around 610 C.E., Muhammad had his first religious experience, where he was instructed to recite by the Angel Gabriel. After a period of introspection and self-doubt, Muhammad accepted his role as God’s prophet and began to preach word of the one God, or Allah in Arabic. His first convert was his wife.

Muhammad’s divine recitations form the Qur’an; unlike the Bible or Hindu epics, it is organized into verses, known as ayat. During one of his many visions, in 621 C.E., Muhammad was taken on the famous Night Journey by the Angel Gabriel, travelling from Mecca to the farthest mosque in Jerusalem, from where he ascended into heaven. The site of his ascension is believed to be the stone around which the Dome of the Rock was built. Eventually in 622, Muhammad and his followers fled Mecca for the city of Yathrib, which is known as Medina today, where his community was welcomed. This event is known as the hijra, or emigration. 622, the year of the hijra (A.H.), marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar, which is still in use today.

Between 625-630 C.E., there were a series of battles fought between the Meccans and Muhammad and the new Muslim community. Eventually, Muhammad was victorious and reentered Mecca in 630.

One of Muhammad’s first actions was to purge the Kaaba of all of its idols (before this, the Kaaba was a major site of pilgrimage for the polytheistic religious traditions of the Arabian Peninsula and contained numerous idols of pagan gods). The Kaaba is believed to have been built by Abraham (or Ibrahim as he is known in Arabic) and his son, Ishmael. The Arabs claim descent from Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar. The Kaaba then became the most important center for pilgrimage in Islam.

In 632, Muhammad died in Medina. Muslims believe that he was the final in a line of prophets, which included Moses, Abraham, and Jesus.

After Muhammad’s death

The century following Muhammad’s death was dominated by military conquest and expansion. Muhammad was succeeded by the four “rightly-guided” Caliphs (khalifa or successor in Arabic): Abu Bakr (632-34 C.E.), Umar (634-44 C.E.), Uthman (644-56 C.E.), and Ali (656-661 C.E.). The Qur’an is believed to have been codified during Uthman’s reign. The final caliph, Ali, was married to Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter and was murdered in 661. The death of Ali is a very important event; his followers, who believed that he should have succeeded Muhammad directly, became known as the Shi’a, meaning the followers of Ali. Today, the Shi’ite community is composed of several different branches, and there are large Shi’a populations in Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain. The Sunnis, who do not hold that Ali should have directly succeeded Muhammad, compose the largest branch of Islam; their adherents can be found across North Africa, the Middle East, as well as in Asia and Europe.

During the seventh and early eighth centuries, the Arab armies conquered large swaths of territory in the Middle East, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Central Asia, despite on-going civil wars in Arabia and the Middle East. Eventually, the Umayyad Dynasty emerged as the rulers, with Abd al-Malik completing the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest surviving Islamic monuments, in 691/2 C.E. The Umayyads reigned until 749/50 C.E., when they were overthrown, and the Abbasid Dynasty assumed the Caliphate and ruled large sections of the Islamic world. However, with the Abbasid Revolution, no one ruler would ever again control all of the Islamic lands.

Arts of the Islamic world

by Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis

What is Islamic Art?

The Dome of the Rock, the Taj Mahal, a Mina’i ware bowl, a silk carpet, a Qur‘an; all of these are examples of Islamic Art. But what is Islamic Art?

Islamic Art is a modern concept, created by art historians in the nineteenth century to categorize and study the material first produced under the Islamic peoples that emerged from Arabia in the seventh century.

Today Islamic Art describes all of the arts that were produced in the lands where Islam was the dominant religion or the religion of those who ruled. Unlike the terms Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist art, which refer only to religious art of these faiths, Islamic art is not used merely to describe religious art or architecture, but applies to all art forms produced in the Islamic World.

Thus, Islamic Art refers not only to works created by Muslim artists, artisans, and architects or for Muslim patrons. It encompasses the works created by Muslim artists for a patron of any faith, including Christians, Jews, or Hindus, and the works created by Jews, Christians, and others, living in Islamic lands, for patrons, Muslim and otherwise.

One of the most famous monuments of Islamic Art is the Taj Mahal, a royal mausoleum, located in Agra, India. Hinduism is majority religion in India; however, because Muslim rulers, most famously the Mughals, dominated large areas of modern-day India for centuries, India has a vast range of Islamic art and architecture. The Great Mosque of Xian, China, is one of the oldest and best preserved mosques in China. First constructed in 742 C.E., the mosque’s current form dates to the fifteenth century C.E. and follows the plan and architecture of a contemporary Buddhist temple. In fact, much Islamic art and architecture was—and still is—created through a synthesis of local traditions and more global ideas.

Islamic Art is not a monolithic style or movement; it spans 1,300 years of history and has incredible geographic diversity—Islamic empires and dynasties controlled territory from Spain to western China at various points in history. However, few if any of these various countries or Muslim empires would have referred to their art as Islamic. An artisan in Damascus thought of his work as Syrian or Damascene—not as Islamic.

As a result of thinking about the problems of calling such art Islamic, certain scholars and major museums, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have decided to omit the term Islamic when they renamed their new galleries of Islamic art. Instead, they are called “Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia,” thereby stressing the regional styles and individual cultures. Thus, when using the phrase, Islamic Art, one should know that it is a useful, but artificial, concept.

In some ways, Islamic Art is a bit like referring to the Italian Renaissance. During the Renaissance, there was no unified Italy; it was a land of independent city-states. No one would have thought of one’s self as an Italian, or of the art they produced as Italian, rather one conceived of one’s self as a Roman, a Florentine, or a Venetian. Each city developed a highly local, remarkable style. At the same time, there are certain underlying themes or similarities that unify the art and architecture of these cities and allow scholars to speak of an Italian Renaissance.

Themes

Similarly, there are themes and types of objects that link the arts of the Islamic World together. Calligraphy is a very important art form in the Islamic World. The Qur’an, written in elegant scripts, represents Allah’s (or God’s) divine word, which Muhammad received directly from Allah during his visions. Quranic verses, executed in calligraphy, are found on many different forms of art and architecture. Likewise, poetry can be found on everything from ceramic bowls to the walls of houses. Calligraphy’s omnipresence underscores the value that is placed on language, specifically Arabic.

Geometric and vegetative motifs are very popular throughout the lands where Islam was once or still is a major religion and cultural force, appearing in the private palaces of buildings such as the Alhambra (in Spain) as well as in the detailed metal work of Safavid Iran. Likewise, certain building types appear throughout the Muslim world: mosques with their minarets, mausolea, gardens, and madrasas (religious schools) are all common. However, their forms vary greatly.

One of the most common misconceptions about the art of the Islamic World is that it is aniconic; that is, the art does not contain representations of humans or animals. Religious art and architecture, almost from the earliest examples, such as the Dome of the Rock, the Aqsa Mosque (both in Jerusalem), and the Great Mosque of Damascus, built under the Umayyad rulers, did not include human figures and animals. However, the private residences of sovereigns, such as Qasr ‘Amra or Khirbat Mafjar, were filled with vast figurative paintings, mosaics, and sculpture.

The study of the arts of the Islamic World has also lagged behind other fields in Art History. There are several reasons for this. First, many scholars are not familiar with Arabic or Farsi (the dominant language in Iran). Calligraphy, particularly Arabic calligraphy, as noted above, is a major art form and appears on almost all types of architecture and arts. Second, the art forms and objects prized in the Islamic world do not correspond to those traditionally valued by art historians and collectors in the Western world. The so-called decorative arts—carpets, ceramics, metalwork, and books—are types of art that Western scholars have traditionally valued less than painting and sculpture. However, the last fifty years has seen a flourishing of scholarship on the arts of the Islamic World.

Arts of the Islamic World

Here, we have decided to use the phrase “Arts of the Islamic World” to emphasize the art that was created in a world where Islam was a dominant religion or a major cultural force, but was not necessarily religious art. Often when the word “Islamic” is used today, it is used to describe something religious; thus using the phrase, Islamic Art, potentially implies, mistakenly, that all of this art is religious in nature. The phrase, “Arts of the Islamic World,” also acknowledges that not all of the work produced in the “Islamic World” was for Muslims or was created by Muslims.

Note on organization from the contributing editor

We have organized the material in this section into three chronological periods: Early, Medieval and Late. When starting to learn about a new area of art, chronological organization often enables students to grasp the material and its fundamentals before going on to more complex analysis, like comparing building types or styles. Within each of these chronological groups, we have focused on creating geographic groups or groupings to organize the material further. The Islamic World was only unified very briefly in its history under the Umayyads (661-750 CE) and the early Abbasids (750-932 CE). Soon various dynasties or rulers simultaneously commanded sections of territory, many of which had no cultural commonalities, aside from their religion.

We are also planning to upload a series of introductory essays on major types of art and architecture from the Islamic World, including carpets and mosques, in addition to essays and videos about specific works of art and architecture. These are forthcoming.

Arabic, Persian and Turkish are complex languages whose transcription from their respective scripts to English has changed considerably over time. For the sake of ease, we have used the most common forms today, omitting the vocalizations. While we have aimed for consistency, we have also tried to use the simplest forms for those who are new to the arts of the Islamic World.

The Kaaba

Prayer and pilgrimage

Pilgrimage to a holy site is a core principle of almost all faiths. The Kaaba, meaning cube in Arabic, is a square building, elegantly draped in a silk and cotton veil. Located in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, it is the holiest shrine in Islam.

In Islam, Muslims pray five times a day and after 624 C.E., these prayers were directed towards Mecca and the Kaaba rather than Jerusalem; this direction (or qibla in Arabic), is marked in all mosques and enables the faithful to know in what direction they should pray. The Qur‘an established the direction of prayer.

All Muslims aspire to undertake the hajj, or the annual pilgrimage, to the Kaaba once in their life if they are able. Prayer five times a day and the hajj are two of the five pillars of Islam, the most fundamental principles of the faith.

Upon arriving in Mecca, pilgrims gather in the courtyard of the Masjid al-Haram around the Kaaba. They then circumambulate (tawaf in Arabic) or walk around the Kaaba, during which they hope to kiss and touch the Black Stone (al-Hajar al-Aswad), embedded in the eastern corner of the Kaaba.

The history and form of the Kaaba

The Kaaba was a sanctuary in pre-Islamic times. Muslims believe that Abraham (known as Ibrahim in the Islamic tradition), and his son, Ismail, constructed the Kaaba. Tradition holds that it was originally a simple unroofed rectangular structure. The Quraysh tribe, who ruled Mecca, rebuilt the pre-Islamic Kaaba in c. 608 C.E. with alternating courses of masonry and wood. A door was raised above ground level to protect the shrine from intruders and flood waters.

Muhammad was driven out of Mecca in 620 C.E. to Yathrib, which is now known as Medina. Upon his return to Mecca in 629/30 C.E., the shrine became the focal point for Muslim worship and pilgrimage. The pre-Islamic Kaaba housed the Black Stone and statues of pagan gods. Muhammad reportedly cleansed the Kaaba of idols upon his victorious return to Mecca, returning the shrine to the monotheism of Ibrahim. The Black Stone is believed to have been given to Ibrahim by the angel Gabriel and is revered by Muslims. Muhammad made a final pilgrimage in 632 C.E., the year of his death, and thereby established the rites of pilgrimage.

Modifications

The Kaaba has been modified extensively throughout its history. The area around the Kaaba was expanded in order to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims by the second caliph, ‘Umar (ruled 634-44). The Caliph ‘Uthman (ruled 644-56) built the colonnades around the open plaza where the Kaaba stands and incorporated other important monuments into the sanctuary.

During the civil war between the caliph Abd al-Malik and Ibn Zubayr who controlled Mecca, the Kaaba was set on fire in 683 C.E. Reportedly, the Black Stone broke into three pieces and Ibn Zubayr reassembled it with silver. He rebuilt the Kaaba in wood and stone, following Ibrahim’s original dimensions and also paved the space around the Kaaba. After regaining control of Mecca, Abd al-Malik restored the part of the building that Muhammad is thought to have designed. None of these renovations can be confirmed through study of the building or archaeological evidence; these changes are only outlined in later literary sources.

Reportedly under the Umayyad caliph al-Walid (ruled 705-15), the mosque that encloses the Kaaba was decorated with mosaics like those of the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus. By the seventh century, the Kaaba was covered with kiswa, a black cloth that is replaced annually during the hajj.

Under the early Abbasid Caliphs (750-1250), the mosque around the Kaaba was expanded and modified several times. According to travel writers, such as the Ibn Jubayr, who saw the Kaaba in 1183, it retained the eighth century Abbasid form for several centuries. From 1269-1517, the Mamluks of Egypt controlled the Hijaz, the highlands in western Arabia where Mecca is located. Sultan Qaitbay (ruled 1468-96) built a madrasa (a religious school) against one side of the mosque. Under the Ottoman sultans, Süleyman I (ruled 1520-1566) and Selim II (ruled 1566-74), the complex was heavily renovated. In 1631, the Kaaba and the surrounding mosque were entirely rebuilt after floods had demolished them in the previous year. This mosque, which is what exists today, is composed of a large open space with colonnades on four sides and with seven minarets, the largest number of any mosque in the world. At the center of this large plaza sits the Kaaba, as well as many other holy buildings and monuments.

The last major modifications were carried out in the 1950s by the government of Saudi Arabia to accommodate the increasingly large number of pilgrims who come on the hajj. Today the mosque covers almost forty acres.

The Kaaba today

Today, the Kaaba is a cubical structure, unlike almost any other religious structure. It is fifteen meters tall and ten and a half meters on each side; its corners roughly align with the cardinal directions. The door of the Kaaba is now made of solid gold; it was added in 1982. The kiswa, a large cloth that covers the Kaaba, which used to be sent from Egypt with the hajj caravan, today is made in Saudi Arabia. Until the advent of modern transportation, all pilgrims undertook the often dangerous hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca in a large caravan across the desert, leaving from Damascus, Cairo, or other major cities in Arabia, Yemen or Iraq.

The numerous changes to the Kaaba and its associated mosque serve as good reminder of how often buildings, even sacred ones, were renovated and remodeled either due to damage or to the changing needs of the community.

Only Muslims may visit the holy cities of Mecca and Medina today.

Introduction to mosque architecture

From Indonesia to the United Kingdom, the mosque in its many forms is the quintessential Islamic building. The mosque, masjid in Arabic, is the Muslim gathering place for prayer. Masjid simply means “place of prostration.” Though most of the five daily prayers prescribed in Islam can take place anywhere, all men are required to gather together at the mosque for the Friday noon prayer.

Mosques are also used throughout the week for prayer, study, or simply as a place for rest and reflection. The main mosque of a city, used for the Friday communal prayer, is called a jami masjid, literally meaning “Friday mosque,” but it is also sometimes called a congregational mosque in English. The style, layout, and decoration of a mosque can tell us a lot about Islam in general, but also about the period and region in which the mosque was constructed.

The home of the Prophet Muhammad is considered the first mosque. His house, in Medina in modern-day Saudi Arabia, was a typical 7th-century Arabian style house, with a large courtyard surrounded by long rooms supported by columns. This style of mosque came to be known as a hypostyle mosque, meaning “many columns.” Most mosques built in Arab lands utilized this style for centuries.

Common features

The architecture of a mosque is shaped most strongly by the regional traditions of the time and place where it was built. As a result, style, layout, and decoration can vary greatly. Nevertheless, because of the common function of the mosque as a place of congregational prayer, certain architectural features appear in mosques all over the world.

Sahn (courtyard)

The most fundamental necessity of congregational mosque architecture is that it be able to hold the entire male population of a city or town (women are welcome to attend Friday prayers, but not required to do so). To that end congregational mosques must have a large prayer hall. In many mosques this is adjoined to an open courtyard, called a sahn. Within the courtyard one often finds a fountain, its waters both a welcome respite in hot lands, and important for the ablutions (ritual cleansing) done before prayer.

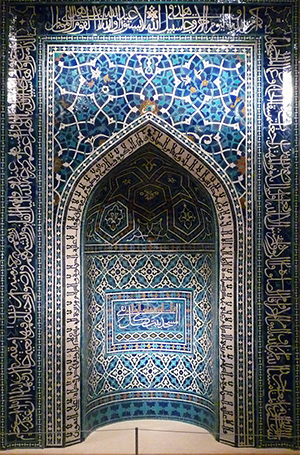

Another essential element of a mosque’s architecture is a mihrab—a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of Mecca, towards which all Muslims pray. Mecca is the city in which the Prophet Muhammad was born, and the home of the most important Islamic site, the Kaaba. The direction of Mecca is called the qibla, and so the wall in which the mihrab is set is called the qibla wall. No matter where a mosque is, its mihrab indicates the direction of Mecca (or as near that direction as science and geography were able to place it). Therefore, a mihrab in India will be to the west, while a one in Egypt will be to the east. A mihrab is usually a relatively shallow niche, as in the example from Egypt, above. In the example from Spain, shown right, the mihrab’s niche takes the form of a small room, this is more rare.

Minaret (tower)

One of the most visible aspects of mosque architecture is the minaret, a tower adjacent or attached to a mosque, from which the call to prayer is announced.

Minarets take many different forms—from the famous spiral minaret of Samarra, to the tall, pencil minarets of Ottoman Turkey. Not solely functional in nature, the minaret serves as a powerful visual reminder of the presence of Islam.

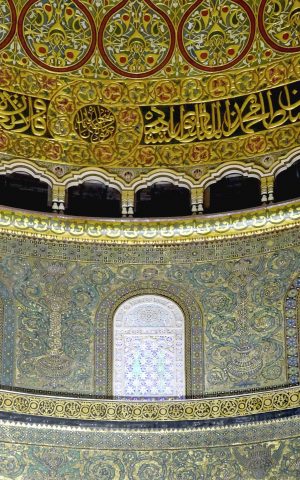

Qubba (dome)

Most mosques also feature one or more domes, called qubba in Arabic. While not a ritual requirement like the mihrab, a dome does possess significance within the mosque—as a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven. The interior decoration of a dome often emphasizes this symbolism, using intricate geometric, stellate, or vegetal motifs to create breathtaking patterns meant to awe and inspire. Some mosque types incorporate multiple domes into their architecture (as in the Ottoman Süleymaniye Mosque pictured at the top of the page), while others only feature one. In mosques with only a single dome, it is invariably found surmounting the qibla wall, the holiest section of the mosque. The Great Mosque of Kairouan, in Tunisia (not pictured) has three domes: one atop the minaret, one above the entrance to the prayer hall, and one above the qibla wall.

Because it is the directional focus of prayer, the qibla wall, with its mihrab and minbar, is often the most ornately decorated area of a mosque. The rich decoration of the qibla wall is apparent in this image of the mihrab and minbar of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan in Cairo, Egypt (see image higher on the page).

Furnishings

There are other decorative elements common to most mosques. For instance, a large calligraphic frieze or a cartouche with a prominent inscription often appears above the mihrab. In most cases the calligraphic inscriptions are quotations from the Qur’an, and often include the date of the building’s dedication and the name of the patron. Another important feature of mosque decoration are hanging lamps, also visible in the photograph of the Sultan Hasan mosque. Light is an essential feature for mosques, since the first and last daily prayers occur before the sun rises and after the sun sets. Before electricity, mosques were illuminated with oil lamps. Hundreds of such lamps hung inside a mosque would create a glittering spectacle, with soft light emanating from each, highlighting the calligraphy and other decorations on the lamps’ surfaces. Although not a permanent part of a mosque building, lamps, along with other furnishings like carpets, formed a significant—though ephemeral—aspect of mosque architecture.

Mosque patronage

Most historical mosques are not stand-alone buildings. Many incorporated charitable institutions like soup kitchens, hospitals, and schools. Some mosque patrons also chose to include their own mausoleum as part of their mosque complex. The endowment of charitable institutions is an important aspect of Islamic culture, due in part to the third pillar of Islam, which calls for Muslims to donate a portion of their income to the poor.

The commissioning of a mosque would be seen as a pious act on the part of a ruler or other wealthy patron, and the names of patrons are usually included in the calligraphic decoration of mosques. Such inscriptions also often praise the piety and generosity of the patron. For instance, the mihrab now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, bears the inscription:

And he [the Prophet], blessings and peace be upon him, said: “Whoever builds a mosque for God, even the size of a sand-grouse nest, based on piety, [God will build for him a palace in Paradise].”

The patronage of mosques was not only a charitable act therefore, but also, like architectural patronage in all cultures, an opportunity for self-promotion. The social services attached the mosques of the Ottoman sultans are some of the most extensive of their type. In Ottoman Turkey the complex surrounding a mosque is called a kulliye. The kulliye of the Mosque of Sultan Suleyman, in Istanbul, is a fine example of this phenomenon, comprising a soup kitchen, a hospital, several schools, public baths, and a caravanserai (similar to a hostel for travelers). The complex also includes two mausoleums for Sultan Suleyman and his family members.

Arts of the Islamic world: The early period

The caliphates

The umbrella term “Islamic art” casts a pretty big shadow, covering several continents and more than a dozen centuries. So to make sense of it, we first have to first break it down into parts. One way is by medium—say, ceramics or architecture—but this method of categorization would entail looking at works that span three continents. Geography is another means of organization, but modern political boundaries rarely match the borders of past Islamic states.

A common solution is to consider instead, the historical caliphates (the states ruled by those who claimed legitimate Islamic rule) or dynasties. Though these distinctions are helpful, it is important to bear in mind that these are not discrete groups that produced one particular style of artwork. Artists throughout the centuries have been affected by the exchange of goods and ideas and have been influenced by one another.

Umayyad (661-750)

Four leaders, known as the Rightly Guided Caliphs, continued the spread of Islam immediately following the death of the Prophet. It was following the death of the fourth caliph that Mu’awiya seized power and established the Umayyad caliphate, the first Islamic dynasty. During this period, Damascus became the capital and the empire expanded West and East.

The first years following the death of Muhammad were, of course, formative for the religion and its artwork. The immediate needs of the religion included places to worship (mosques) and holy books (Korans) to convey the word of God. So, naturally, many of the first artistic projects included ornamented mosques where the faithful could gather and Korans with beautiful calligraphy.

Because Islam was still a very new religion, it had no artistic vocabulary of its own, and its earliest work was heavily influenced by older styles in the region. Chief among these sources were the Coptic tradition of present-day Egypt and Syria, with its scrolling vines and geometric motifs, Sassanian metalwork and crafts from what is now Iraq with their rhythmic, sometimes abstracted qualities, and naturalistic Byzantine mosaics depicting animals and plants.

These elements can be seen in the earliest significant work from the Umayyad period, the most important of which is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This stunning monument incorporates Coptic, Sassanian, and Byzantine elements in its decorative program and remains a masterpiece of Islamic architecture to this day.

Remarkably, just one generation after the religion’s inception, Islamic civilization had produced a magnificent, if singular, monument. While the Dome of the Rock is considered an influential work, it bears little resemblance to the multitude of mosques created throughout the rest of the caliphate. It is important to point out that the Dome of the Rock is not a mosque. A more common plan, based on the house of the Prophet, was used for the vast majority of mosques throughout the Arab peninsula and the Maghreb. Perhaps the most remarkable of these is the Great Mosque of Córdoba (784-786) in Spain, which, like the Dome of the Rock, demonstrates an integration of the styles of the existing culture in which it was created.

Abbasid (750-1258)

The Abbasid revolution in the mid-eighth century ended the Umayyad dynasty, resulted in the massacre of the Umayyad caliphs (a single caliph escaped to Spain, prolonging Umayyad work after dynasty) and established the Abbasid dynasty in 750. The new caliphate shifted its attention eastward and established cultural and commercial capitals at Baghdad and Samarra.

The Umayyad dynasty produced little of what we would consider decorative arts (like pottery, glass, metalwork), but under the Abbasid dynasty production of decorative stone, wood and ceramic objects flourished. Artisans in Samarra developed a new method for carving surfaces that allowed for curved, vegetal forms (called arabesques) which became widely adopted. There were also developments in ceramic decoration. The use of luster painting (which gives ceramic ware a metallic sheen) became popular in surrounding regions and was extensively used on tile for centuries. Overall, the Abbasid epoch was an important transitional period that disseminated styles and techniques to distant Islamic lands.

The Abbasid empire weakened with the establishment and growing power of semi-autonomous dynasties throughout the region, until Baghdad was finally overthrown in 1258. This dissolution signified not only the end of a dynasty, but marked the last time that the Arab-Muslim empire would be united as one entity.

The Umayyads, an introduction

The Dome of the Rock. The Great Mosque in Damascus. The Great Mosque in Córdoba. These remarkable architectural and artistic achievements are associated with the Umayyads, “first” dynasty of the Islamic World.

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 C.E., there was a series of four rulers, known as the Rightly Guided Caliphs: Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and, lastly, Muhammad’s son-in-law, ‘Ali.

While the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam dispute the order of succession (specifically whether ‘Ali should have rightfully been Muhammad’s first successor), ‘Ali’s assassination marked a crossroad for early Muslims and resulted a series of civic wars (or fitnas).

Mu‘awiya and ‘Abd al-Malik

Mu‘awiya, then governor of Syria under ‘Ali, seized power after ‘Ali’s death. After a number of victories, Mu‘awiya emerged as the sole ruler of the Muslim world. He consolidated the early Muslim conquests in the Middle East and expanded the empire. Mu‘awiya established his capital at Damascus, shifting his power base north of Mecca and Medina in the Arab heartland. Mu‘awiya also instituted political and bureaucratic systems that allowed for the effective rule of the nascent Islamic empire and the expansion of the economy.

Mu‘awiya’s death in 680 resulted another wave of civil and religious wars, during which the Umayyads lost control of Mecca and Medina. Mu‘awiya’s son, ‘Abd al-Malik, eventually emerged victorious. Like the Roman emperors before him and his Byzantine contemporaries, ‘Abd al-Malik saw architecture and art as a means to express his authority and to provide the new religion of Islam with a powerful visual language that could convey the theology, values, and ideas of Islam to both Muslims and those who had been conquered.

‘Abd al-Malik built the Dome of the Rock on the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, which employed inscriptions, gold and blue mosaics, and innovative architecture to create one of the world’s most exceptional buildings. Adjacent to the Dome of the Rock, he also erected a permanent mosque (replacing an earlier temporary mosque), known as the Aqsa mosque. It is the third holiest mosque in the Islamic world after those at Mecca and Medina.

During ‘Abd al-Malik’s reign, Arabic took hold as the language of bureaucracy and of the elite. The stability afforded by his reign also meant that trade flourished, as goods and people moved with ease within the boundaries of the Islamic world. ‘Abd al-Malik also undertook public works, constructing roads, canals, and dams.

Coinage Reform

‘Abd al-Malik also radically reformed coinage. Until 697 C.E., Islamic coinage deployed figural imagery, which was modeled on Byzantine and Sasanian coins. These coins included images, such as the standing caliph type, and were accompanied by Arabic inscriptions (or, in the case of coins minted in Iran, Pahlavi, or Middle Persian, inscriptions).

However, after 697 C.E., coins were minted with religious inscriptions in Arabic, the date, and the mint’s location. Since coins circulated widely, the coins helped articulate the new faith and political authority to both Muslims and the peoples that they had conquered. The uniform coinage also facilitated trade, as there was now a single currency with standardized iconography and denominations.

The inscription on the observe (on the left above) announces the creed of Muslims, the central inscription reads: There is no God but God, He is alone, He has no associate. The marginal inscription reads: Muhammad is the Messenger of God. He sent him with Guidance and the true religion that he might overcome all [religions even though the polytheists hate it]. Translation: British Museum. ‘Abd al-Malik was succeeded by his son, al-Walid I, who built the Great Mosque in Damascus (see photo near top of page) — another of the most important surviving monuments from the early Islamic period. Built using the tax revenue of Syria for seven years, the Great Mosque proclaimed the achievements of Islam in architectural and artistic form.

“Desert Castles”

al-Walid was succeeded by a series of male relatives who ruled until 749 C.E. Their main artistic and architectural achievement was the construction of what scholars have traditionally called the “Desert Castles.” These “castles” are better described as imperial or aristocratic residences that took the form of hunting lodges, rural residences, and urban palaces. Like the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus, these residences expressed the authority and status of the Umayyad rulers; however, they use a distinctively secular architectural language.

These residences included audience halls, baths, and mosques, as well as extensive grounds. The residences were richly decorated with figural mosaics, paintings, and sculpture, which helped to create a luxurious environment for feasting, hunting, and the recitation of poetry and other courtly pursuits. These famous residences include Qusayr ‘Amra, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Mshatta, and others.

Built by al-Walid II, Qusayr ‘Amra (in Jordan) is composed of an audience hall and bath complex with rich wall paintings. Khirbat al-Mafjar, located outside Jericho in the West Bank, has rich floor mosaics, including deer and a lion under a treat, as well as an extensive program of figurative sculpture. A statue of the caliph, standing on a base decorated with lions (a symbol of royal power) greeted visitors, a clear articulation of authority and power. While the form of the standing caliph was no longer on Islamic coins, the image was still potent.

The frieze from Mshatta, an unfinished residence in Jordan, is now in the Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin. These residences are particularly important, as they confirm that since the inception of Islamic art figurative representation has been an important aspect of Islamic Art. However, figurative art is almost always used in the secular realm, while religious art is aniconic (without the representation of human figures).

The glory of the Umayyads was not to last; almost all of the Umayyad princes were massacred in 749 by their rivals, the Abbasids, in what scholars call the “Abbasid Revolution.”

The only Umayyad prince to survive was ‘Abd al-Rahman I, and he escaped to found his own dynasty in Spain. Rooted in the Syrian traditions of his forefathers (and supported by Syrian immigrants), he established an alternative caliphate to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad.

In 786, he founded the Great Mosque in Córdoba. Although little of his original foundation survives, the later modifications and decoration, particularly the use of mosaics on the domes of mihrab and maqsura, were a clear evocation of the glorious Syrian past.

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

The Dome of the Rock is a building of extraordinary beauty, solidity, elegance, and singularity of shape… Both outside and inside, the decoration is so magnificent and the workmanship so surpassing as to defy description. The greater part is covered with gold so that the eyes of one who gazes on its beauties are dazzled by its brilliance, now glowing like a mass of light, now flashing like lightning.

—Ibn Battuta (14th century travel writer)

A glorious mystery

One of the most iconic images of the Middle East is undoubtedly the Dome of the Rock shimmering in the setting sun of Jerusalem. Sitting atop the Haram al-Sharif, the highest point in old Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock’s golden-color Dome and Turkish Faience tiles dominates the cityscape of Old Jerusalem and in the 7th century served as a testament to the power of the new faith of Islam. The Dome of the Rock is one of the earliest surviving buildings from the Islamic world. This remarkable building is not a mosque, as is commonly assumed and scholars still debate its original function and meaning.

Between the death of the prophet Muhammad in 632 and 691/2, when the Dome of the Rock was completed, there was intermittent warfare in Arabia and Holy Land around Jerusalem. The first Arab armies who emerged from the Arabian peninsula were focused on conquering and establishing an empire—not building.

Thus, the Dome of the Rock was one of the first Islamic buildings ever constructed. It was built between 685 and 691/2 by Abd al-Malik, probably the most important Umayyad caliph, as a religious focal point for his supporters, while he was fighting a civil war against Ibn Zubayr. When Abd al-Malik began construction on the Dome of the Rock, he did not have control of the Kaaba, the holiest shrine in Islam, which is located in Mecca.

The Dome is located on the Haram al-Sharif, an enormous open-air platform that now houses Al-Aqsa mosque, madrasas and several other religious buildings. Few places are as holy for Christians, Jews and Muslims as the Haram al-Sharif. It is the Temple Mount, the site of the Jewish second temple, which the Roman Emperor Titus destroyed in 70 C.E. while subduing the Jewish revolt; a Roman temple was later built on the site. The Temple Mount was abandoned in Late Antiquity.

The Rock in the Dome of the Rock

At the center of the Dome of the Rock sits a large rock, which is believed to be the location where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son Ismail (Isaac in the Judeo/Christian tradition). Today, Muslims believe that the Rock commemorates the night journey of Muhammad. One night the Angel Gabriel came to Muhammad while he slept near the Kaaba in Mecca and took him to al-Masjid al-Aqsa (the farthest mosque) in Jerusalem. From the Rock, Muhammad journeyed to heaven, where he met other prophets, such as Moses and Christ, witnessed paradise and hell and finally saw God enthroned and circumambulated by angels.

The Rock is enclosed by two ambulatories (in this case the aisles that circle the rock) and an octagonal exterior wall. The central colonnade (row of columns) was composed of four piers and twelve columns supporting a rounded drum that transitions into the two-layered dome more than 20 meters in diameter.

The colonnades are clad in marble on their lower registers, and their upper registers are adorned with exceptional mosaics. The ethereal interior atmosphere is a result of light that pours in from grilled windows located in the drum and exterior walls. Golden mosaics depicting jewels shimmer in this glittering light. Byzantine and Sassanian crowns in the midst of vegetal motifs are also visible.

The Byzantine Empire stood to the North and to the West of the new Islamic Empire until 1453, when its capital, Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Turks. To the East, the old Sasanian Empire of Persia imploded under pressure from the Arabs, but nevertheless provided winged crown motifs that can be found in the Dome of the Rock.

Mosaics

Wall and ceiling mosaics became very popular in Late Antiquity and adorn many Byzantine churches, including San Vitale in Ravenna and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Thus, the use of mosaics reflects an artistic tie to the world of Late Antiquity. Late Antiquity is a period from about 300-800, when the Classical world dissolves and the Medieval period emerges.

The mosaics in the Dome of the Rock contain no human figures or animals. While Islam does not prohibit the use of figurative art per se, it seems that in religious buildings, this proscription was upheld. Instead, we see vegetative scrolls and motifs, as well as vessels and winged crowns, which were worn by Sasanian kings. Thus, the iconography of the Dome of the Rock also includes the other major pre-Islamic civilization of the region, the Sasanian Empire, which the Arab armies had defeated.

A reference to burial places

The building enclosing the Rock also seems to take its form from the imperial mausolea (the burial places) of Roman emperors, such as Augustus or Hadrian. Its circular form and Dome also reference the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The circular Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem was built to enclose the tomb of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Dome of the Rock have domes that are almost identical in size; this suggests that the elevated position of the Dome of the Rock and the comparable size of its dome was a way that Muslims in the late 8th century proclaimed the superiority of their newly formed faith over Christians.

The inscription

The Dome of the Rock also contains an inscription, 240 meters long, that includes some of the earliest surviving examples of verses from the Qur‘an – in an architectural context or otherwise. The bismillah (in the name of God, the merciful and compassionate), the phrase that starts each verse of the Qu’ran, and the shahada, the Islamic confession of faith, which states that there is only one God and Muhammad is his prophet, are also included in the inscription. The inscription also refers to Mary and Christ and proclaim that Christ was not divine but a prophet. Thus the inscription also proclaims some of the core values of the newly formed religion of Islam.

Below the Rock is a small chamber, whose purpose is not fully understood even to this day. For those who are fortunate enough to be able to enter the Dome of the Rock, the experience is moving, regardless of one’s faith.

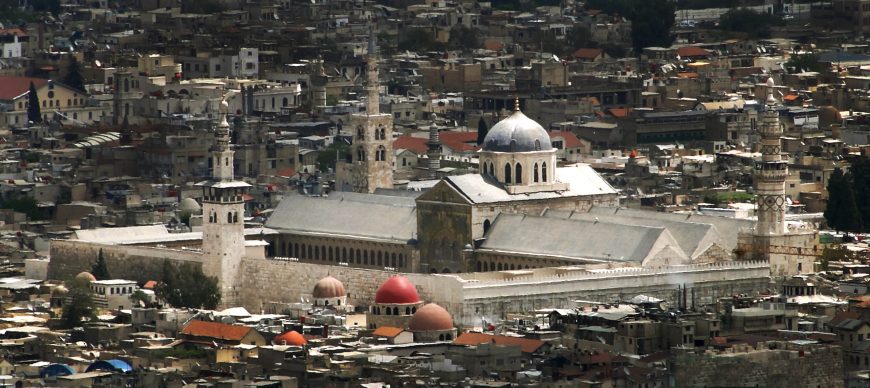

The Great Mosque of Damascus

To understand the importance of the Great Mosque of Damascus, built by the Umayyad caliph, al-Walid II between 708 and 715 C.E., we need to look into the recesses of time. Damascus is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world, with archaeological remains dating from as early as 9000 B.C.E., and sacred spaces have been central to the Old City of Damascus ever since. As early as the 9th century B.C.E., a temple was built to Hadad-Ramman, the Semitic god of storm and rain. Though the exact form and shape of this temple is unknown, a bas-relief with a sphinx, believed to come from this temple, was reused in the northern wall of the city’s Great Mosque.

From Zeus to Saul

Alexander the Great marched through Syria on his way to Persia and India and while he likely passed through Damascus, it was his successors—the Ptolemies and the Selecuids—who would shape Syria. Until 63 B.C.E., Damascus would remain under the political control and cultural influence of these Greek dynasties. While almost nothing survives archaeologically from this period, Greek became the dominant language and the culture became Hellenized (influenced by Greek culture). At this time, the temple of Hadad was converted into a Temple of Zeus-Hadad. Zeus was a natural choice for assimilation; he ruled the Greek pantheon and was associated with weather and, of course, thunder bolts. Many Greek (and later Roman) gods were combined with local gods across the lands controlled by the Greeks and then the Romans. This allowed the conquering culture to integrate their new subjects into their religion, while also accepting local traditions—thus helping to make new foreign masters more agreeable to subjugated locals. The Zeus-Hadad temple dominated the Greek city and was connected by a main thoroughfare to the new agora, or market area, located to the east. At the center of a temenos, an enclosed and sacred precinct, stood the temple to Zeus-Hadad, which had a cella (the room in which a statue of the god stood).

After the Greeks came the invading Roman armies (led by Pompey in 63 B.C.E.). Under Herod the Great (the local pro-Roman ruler), the city of Damascus was transformed. Herod built a theater whose remains can still be seen in the basement and ground floor of a house called Bayt al- ‘Aqqad (now the Danish Institute). The temple was modified at this time when two concentric walls were added to enclose the precinct (or peribolos) of the temple and two monumental gates, or propylaea, were added on the western and eastern ends of the precinct which now measured 117,000 square feet. At its center was the temple with a cella for the worship of Jupiter-Hadad. It was now a truly monumental temple. The western gate was refurbished and embellished under the Roman Severan dynasty (193–235 C.E.), additions that remain visible today.

Although the great temple to Jupiter marked the spiritual heart of the city for several centuries, just as it was completed, a new cult to a single God was developing: Christianity. Saul, or Paul as he is known after his conversion, is said to have converted on the road to Damascus (Acts 9.1–2; 9.5–6). Blinded by a light, he was led to the home of a Jew named Judas on Straight Street, the decumanus or main east-west street in Damascus. Ananias had a vision that told him to go and care for Paul and when he touched Paul at Judas’ house, the scales fell from Paul’s eyes and he could see.

Unsurprisingly, once Christianity was widely adopted in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, the temple to Jupiter was once again converted, this time into a cathedral dedicated to John the Baptist. This church is attributed to the Emperor Theodosius in 391 C.E. The exact location of the church is unknown, but it is thought to have been located in the western part of the temenos. It was probably one of the largest churches in the Christian world and served as a major center of Christianity until 636 C.E. when the city was once again conquered, this time by Muslim Arabs. Damascus was a key city, as it provided access to the sea and to the desert. When it was clear that the city was going to fall, the defeated Christians and conquering Muslims negotiated the city’s surrender. The Muslims agreed to respect the lives, property and churches of the Christians. Christians retained control of their cathedral, although Muslim worshippers reportedly used the southern wall of the compound when they prayed towards Mecca.

al-Walid’s mosque

When Damascus became the capital of the Umayyad dynasty, the early 8th century caliph al-Walid envisioned a beautiful mosque at the heart of his new capital city, one that would rival any of the great religious buildings of the Christian world. The growing population of Muslims also required a large congregational mosque (a congregational mosque is a mosque where the community of believers, originally only men, would come to worship and hear a sermon on Fridays — it was typically the most important mosque in a city or in a neighborhood of a large city). The Great Mosque of Damascus was commissioned in 708 C.E. and was completed in 714/15 C.E. It was paid for with the state tax revenue raised over the course of seven years, a prodigious sum of money. The result of this investment was an architectural tour de force where mosaics and marbles created a truly awe-inspiring space. The Great Mosque of Damascus is one of the earliest surviving congregational mosques in the world. The mosque’s location and organization were directly influenced by the temples and the church that preceded it. It was built into the Roman temple wall and it reuses older building materials (called spolia by archaeologists) in its walls, including a beam with a Greek inscription that was originally part of the church.

The complex is composed of a prayer hall and a large open courtyard with a fountain for ablutions (washing) before prayer. Before the civil war that began in 2011, the courtyard of the mosque functioned as a social space for Damascenes, where families and friends could meet and talk while children chased each other through the colonnade, and where tourists once snapped photographs. It was a wonderful place of peace in a busy city. The courtyard contains an elevated treasury and a structure know as the “Dome of the Clock,” whose purpose is not fully understood. There are tower-like minarets at the corners of the mosque and courtyard; the southern minarets are built on the Roman-Byzantine corner towers and are probably the earliest minarets in Syria. Again, the earlier structures directly influenced the present form.

From the courtyard, one would enter the prayer hall. The prayer hall takes its form from Christian basilicas (which are in turn derived from ancient Roman law courts). However, there is no apse towards which one would pray. Rather the faithful pray facing the qibla wall. The qibla wall has a niche (mihrab), which focuses the faithful in their prayers. In line with the mihrab of the Great Mosque is a massive dome and a transept to accommodate a large number of worshippers. The façade of the transept facing the courtyard is decorated on the exterior with rich mosaics.

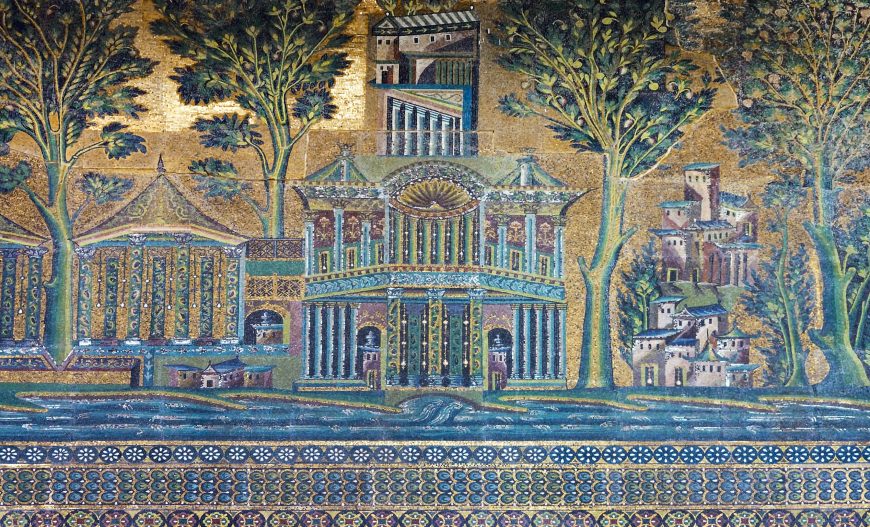

Although a fire in the 1890s badly damaged the courtyard and interior, much of the rich mosaic program, which dates primarily to the early 8th century, has survived. The mosaics are aniconic (non-figurative). Islamic religious art lacks figures, and so this is an early example of this tradition. The mosaics are a beautiful mix of trees, landscapes, and uninhabited architecture, rendered in stunning gold, greens, and blues. Later sources note that there were inscriptions and mosaics in the prayer hall, like the Umayyad mosque in Medina, but these have not survived.

Mediterranean influences

The architecture and the plants depicted in the mosaics have clear origins in the artistic traditions of the Mediterranean. Acanthus-like scrolls of greenery can be seen. Not only are they similar to those found in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, but similar motifs can be seen in the sculpture of the ancient Roman Ara Pacis.

There are other strong connections to the visual traditions of the Mediterranean world — to Ptolemaic architecture in Egypt, to the architecture of the Treasury at Petra, and the wall paintings of Pompeii. By using these well-established architectural and artistic forms, the Umayyads were coopting and transforming the artistic traditions of earlier, once dominant religions and empires. The use of such media and imagery allowed the new faith to assert its supremacy. The mosaics and architecture of the Great Mosque signaled this new prominence to an audience that was still predominantly Christian, that Islam was as powerful a religion as Christianity. The subject of the mosaics remains debated to this day, with scholars arguing that the mosaics either represent heaven, based on an interpretation of Quranic verse, or the local landscape (including the Barada River).

Scholars traditionally attributed the creation of these mosaics to artisans from Constantinople because a twelfth-century text claimed that the Byzantine emperor had sent mosaicists to Damascus. However, recent scholarship has challenged this as the text that made this claim was written from a Christian perspective and is much later than the mosaics. Scholars now think that the mosaics were either created by local artisans, or possibly by Egyptian artisans (since Egypt also has a long tradition of decorating domes with mosaics).

The influence of the mosque and its artistry can be seen as far as a way as Cordoba, Spain, where the 8th century Umayyad ruler, Abd al-Rahman (the only survivor of a massive family assassination that sparked the Abbasid Revolution), had fled. The mihrab and the dome above in the Great Mosque of Cordoba was decorated in blue, green and gold mosaics, evoking his lost Syrian homeland.

The Umayyad mosque of Damascus is truly one of the great mosques of the early Islamic world and it is remains one of the world’s most important monuments. Unlike many of Syria’s historic buildings and archaeological sites, the mosque has survived the Syrian Civil War relatively unscathed and hopefully, will one day again welcome Syrians and tourists alike.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba

Known locally as Mezquita-Catedral, the Great Mosque of Córdoba is one of the oldest structures still standing from the time Muslims ruled Al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia including most of Spain, Portugal, and a small section of Southern France) in the late 8th century. Córdoba is a two hour train ride south of Madrid, and draws visitors from all over the world.

Temple/church/mosque/church

The buildings on this site are as complex as the extraordinarily rich history they illustrate. Historians believe that there had first been a temple to the Roman god, Janus, on this site. The temple was converted into a church by invading Visigoths who seized Córdoba in 572. Next, the church was converted into a mosque and then completely rebuilt by the descendants of the exiled Umayyads—the first Islamic dynasty who had originally ruled from their capital Damascus (in present-day Syria) from 661 until 750.

A new capital

Following the overthrow of his family (the Umayyads) in Damascus by the incoming Abbasids, Prince Abd al-Rahman I escaped to southern Spain. Once there, he established control over almost all of the Iberian Peninsula and attempted to recreate the grandeur of Damascus in his new capital, Córdoba. He sponsored elaborate building programs, promoted agriculture, and even imported fruit trees and other plants from his former home. Orange trees still stand in the courtyard of the Mosque of Córdoba, a beautiful, if bittersweet reminder of the Umayyad exile.

The hypostyle hall

The building itself was expanded over two hundred years. It is comprised of a large hypostyle prayer hall (hypostyle means, filled with columns), a courtyard with a fountain in the middle, an orange grove, a covered walkway circling the courtyard, and a minaret (a tower used to call the faithful to prayer) that is now encased in a squared, tapered bell tower. The expansive prayer hall seems magnified by its repeated geometry. It is built with recycled ancient Roman columns from which sprout a striking combination of two-tiered, symmetrical arches, formed of stone and red brick.

The focal point in the prayer hall is the famous horseshoe arched mihrab or prayer niche. A mihrab is used in a mosque to identify the wall that faces Mecca—the birth place of Islam in what is now Saudi Arabia. This is practical as Muslims face toward Mecca during their daily prayers. The mihrab in the Great Mosque of Córdoba is framed by an exquisitely decorated arch behind which is an unusually large space, the size of a small room. Gold tesserae (small pieces of glass with gold and color backing) create a dazzling combination of dark blues, reddish browns, yellows and golds that form intricate calligraphic bands and vegetal motifs that adorn the arch.

The horseshoe arch

The horseshoe-style arch was common in the architecture of the Visigoths, the people that ruled this area after the Roman empire collapsed and before the Umayyads arrived. The horseshoe arch eventually spread across North Africa from Morocco to Egypt and is an easily identified characteristic of Western Islamic architecture (though there are some early examples in the East as well).

The dome

Above the mihrab, is an equally dazzling dome. It is built of crisscrossing ribs that create pointed arches all lavishly covered with gold mosaic in a radial pattern. This astonishing building technique anticipates later Gothic rib vaulting, though on a more modest scale.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba is a prime example of the Muslim world’s ability to brilliantly develop architectural styles based on pre-existing regional traditions. Here is an extraordinary combination of the familiar and the innovative, a formal stylistic vocabulary that can be recognized as “Islamic” even today.

Folio from a Qur’an

The Qur’an: From recitation to book

The Qur’an is the sacred text of Islam, consisting of the divine revelation to the Prophet Muhammad in Arabic. Over the course of the first century and a half of Islam, the form of the manuscript was adapted to suit the dignity and splendor of this divine revelation. However, the word Qur’an, which means “recitation,” suggests that manuscripts were of secondary importance to oral tradition. In fact, the 114 suras (or chapters) of the Qur’an were compiled into a textual format, organized from longest to shortest, only after the death of Muhammad, although scholars still debate exactly when this might have occurred.

This two-page spread (or bifolium) of a Qur’an manuscript, which contains the beginning of Surat Al-‘Ankabut (The Spider), is now in the collection of The Morgan Library and Museum in New York. Other folios that appear to be from the same Qur’an survive in the Chester Beatty Library (Dublin), the Topkapı Palace Museum and the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art (Istanbul), and the National Museum of Syria (Damascus). One page includes an inscription, which states that ʿAbd al-Munʿim Ibn Aḥmad donated the Qur’an to the Great Mosque of Damascus in 298 A.H. (July, 911 C.E.), although we do not know where or how long before this donation the manuscript was produced.

A roadmap for readers

The main text of the mushaf (pronounced muss-hoff), as manuscripts of the Qur’an are known, is written in brown ink. Arabic, the language of the divine word of Islam, is read from right to left. Several consonants share the same basic letterform, and these are usually distinguished from each other by lines or dots placed above or below the letter. Short vowels such as a, u, and i, are not normally written in Arabic, but in order to avoid misreadings of such an important text it quickly became standard to include vowels in the Qur’an. In this manuscript, these short vowels are marked with red circles positioned above, next to, or below the consonants, depending on the vowel.

The text of each sura is further divided into verses by triangles made up of 5 gold circles located at the end of each verse (left).

The title of each sura is written in gold ink, and surrounded by a rectangle, filled here with an undulating golden vine (below). Combined with a rounded palmette extending into the margin of the folio, it allows readers to quickly locate the beginning of each sura.

Because figural imagery such as human or animal forms was considered inappropriate for the ornamentation of sacred monuments and objects, artists relied on vegetal and geometric motifs when they decorated mosques and sacred manuscripts. Vines and palmettes like the ones that surround the sura heading here appear alone in sacred contexts, but they also accompanied animal and human forms in the secular decoration of palaces and textiles.

Planning the proportions of the page

The art of producing a mushaf began well before a pen was ever dipped into ink. The dimensions of each page were calculated before the parchment was cut, and the text was carefully situated relative to the edges of the pages. Each page of costly parchment (or vellum) in this Qur’an is larger than a standard sheet of printer paper, and contains only nine lines of calligraphy. These materials suggest both the dignity of the sacred text and the wealth of its patron, who was probably a member of the aristocratic elite.

In addition to the high quality and large quantity of materials used, the deliberate geometric planning of the page conveys the importance of the text that it contains. As in many of the mushafs produced between 750 and 1000 C.E., the pages of this manuscript are wider than they are tall.

The text-block of this manuscript has a height-to-width ratio of 2:3, and the width of the text-block is approximately equal to the height of the page. The height of each line of text was derived from the first letter of the alphabet, alif, which was in turn derived from the width of the nib of the reed pen used by the calligraphers to write the text.

Each line was further divided into a set number of “interlines,” which were used to determine the heights of various parts of individual letters. There is no ruling on the parchment, however, so scribes probably placed each sheet of the semi-transparent parchment on a board marked with horizontal guidelines as they wrote. Memorizing and producing the proportions of each pen stroke, however, must have been part of the training of every scribe.

Kufic script and the specialization of scribes

Writing in the tenth century C.E., the Abbasid court secretary Ibn Durustuyah noted that letters of the alphabet were written differently by Qur’anic scribes, professional secretaries, and other copyists. The calligraphic style used by these early scribes of the Qur’an is known today as Kufic. Only two or three of the more than 1300 fragments and manuscripts written in Kufic that survive contain non-Qur’anic content.

Kufic is not so much a single type of handwriting as it is a family of 17 related styles based on common principles, including a preference for strokes of relatively uniform thickness, short straight vertical lines and long horizontal lines, and a straight, horizontal baseline.

Various types of kufic were popular from the seventh century C.E. until the late tenth century C.E. Scribes used a wide reed pen dipped in ink to write. In some letters the angle of the pen was adjusted as the scribe wrote in order to maintain an even thickness throughout the entire letterform, but in others the angle could be held constant in order to produce both very thick and very thin lines. Although letters and even entire words at first appear to consist of a single stroke of the pen, in fact individual letters were often formed using multiple strokes.

The regularity and precision of the penmanship in the fragment from The Morgan Library reveals the skill of the scribes who produced it. Each of them deliberately imitated a single style in order to produce a unified finished product.

Scribes also had some freedom in composing a page. They could emphasize individual words and balance the widths of lines of different length by elongating certain letters horizontally (a technique known as mashq). They could also adjust spacing between words and letters, and even split words between two lines, in order to balance positive and negative space across the page.

In this mushaf, the spaces between non-connecting characters within a word are as wide as the spaces that separate different words (sometimes even wider!). For readers unfamiliar with the text, it is therefore difficult to figure out which letters should be grouped together to form words. This deliberate obfuscation would have slowed down readers, and it suggests that anyone who read aloud from these manuscripts had probably already memorized the text of the Qur’an and used the lavish manuscript only as a kind of mnemonic device.

The Alhambra

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain, is distinct among Medieval palaces for its sophisticated planning, complex decorative programs, and its many enchanting gardens and fountains. Its intimate spaces are built at a human scale that visitors find elegant and inviting.

The Alhambra, an abbreviation of the Arabic: Qal’at al-Hamra, or red fort, was built by the Nasrid Dynasty (1232-1492)—the last Muslims to rule in Spain. Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr (known as Muhammad I) founded the Nasrid Dynasty and secured this region in 1237. He began construction of his court complex, the Alhambra, on Sabika hill the following year.

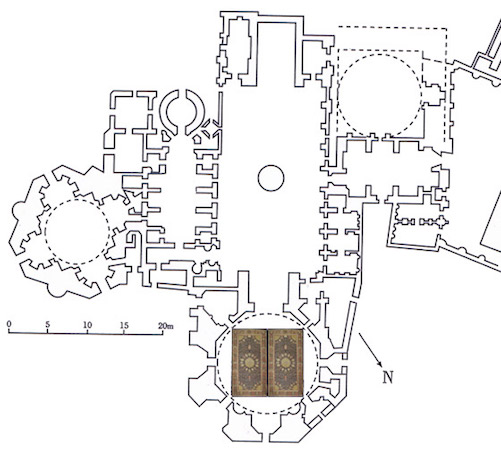

Plan of the Alhambra and Generalife

1,730 meters (1 mile) of walls and thirty towers of varying size enclose this city within a city. Access was restricted to four main gates. The Alhambra’s nearly 26 acres include structures with three distinct purposes, a residence for the ruler and close family, the citadel, Alcazaba—barracks for the elite guard who were responsible for the safety of the complex, and an area called medina (or city), near the Puerta del Vino (Wine Gate), where court officials lived and worked.

The different parts of the complex are connected by paths, gardens and gates but each part of the complex could be blocked in the event of a threat. The exquisitely detailed structures with their highly ornate interior spaces and patios contrast with the plain walls of the fortress exterior.

Three palaces

The Alhambra’s most celebrated structures are the three original royal palaces. These are the Comares Palace, the Palace of the Lions, and the Partal Palace, each of which was built during 14th century. A large fourth palace was later begun by the Christian ruler, Carlos V.

El Mexuar is an audience chamber near the Comares tower at the northern edge of the complex. It was built by Ismail I as a throne room, but became a reception and meeting hall when the palaces were expanded in the 1330s. The room has complex geometric tile dadoes (lower wall panels distinct from the area above) and carved stucco panels that give it a formality suitable for receiving dignitaries (above).

The Comares Palace

Behind El Mexuar stands the formal and elaborate Comares façade set back from a courtyard and fountain. The façade is built on a raised three-stepped platform that might have served as a kind of outdoor stage for the ruler. The carved stucco façade was once painted in brilliant colors, though only traces remain.

A dark winding passage beyond the Comares façade leads to a covered patio surrounding a large courtyard with a pool, now known as the Court of the Myrtles. This was the focal point of the Comares Palace.

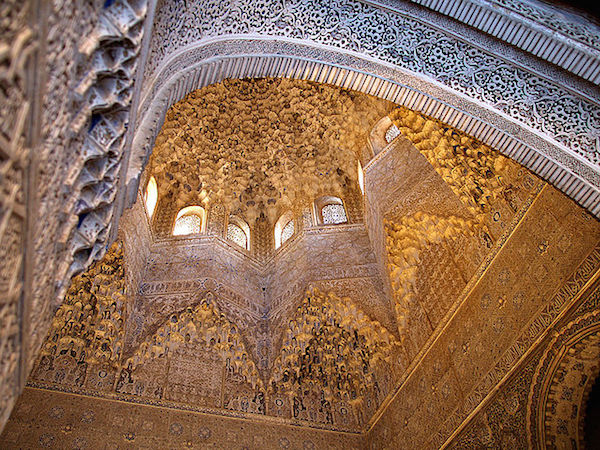

The Alhambra’s largest tower, the Comares Tower, contains the Salón de Comares (Hall of the Ambassadors), a throne room built by Yusuf I (1333-1354). This room exhibits the most diverse decorative and architectural arts contained in the Alhambra.

The double arched windows illuminate the room and provide breathtaking views. Additional light is provided by arched grille (lattice) windows set high in the walls. At eye level, the walls are lavishly decorated with tiles laid in intricate geometric patterns. The remaining surfaces are covered with intricately carved stucco motifs organized in bands and panels of curvilinear patterns and calligraphy.

Palace of the Lions

The Palacio de los Leones (Palace of the Lions) stands next to the Comares Palace but should be considered an independent building. The two structures were connected after Granada fell to the Christians.

Muhammad V built the Palace of the Lions’ most celebrated feature in the 14th century, a fountain with a complex hydraulic system consisting of a marble basin on the backs of twelve carved stone lions situated at the intersection of two water channels that form a cross in the rectilinear courtyard. An arched covered patio encircles the courtyard and displays fine stucco carvings held up by a series of slender columns. Two decorative pavilions protrude into the courtyard on an East–West axis (at the narrow sides of the courtyard), accentuating the royal spaces behind them.

Muqarnas Chamber, Alhambra (photo: Vaughan Williams, CC BY 2.0)To the West, the Sala de los Mocárabes (Muqarnas Chamber), may have functioned as an antechamber and was near the original entrance to the palace. It takes its name from the intricately carved system of brackets called “muqarnas” that hold up the vaulted ceiling.

Across the courtyard, to the East, is the Sala de los Reyes (Hall of the Kings), an elongated space divided into sections using a series of arches leading up to a vaulted muqarnas ceiling; the room has multiple alcoves, some with an unobstructed view of the courtyard, but with no known function.

This room contains paintings on the ceiling representing courtly life. The images were first painted on tanned sheepskins, in the tradition of miniature painting. They use brilliant colors and fine details and are attached to the ceiling rather than painted on it.

There are two other halls in the Palace of the Lions on the northern and southern ends; they are the Sala de las Dos Hermanas (the Hall of the Two Sisters) and the Hall of Abencerrajas (Hall of the Ambassadors). Both were residential apartments with rooms on the second floor. Each also have a large domed room sumptuously decorated with carved and painted stucco in muqarnas forms with elaborate and varying star motifs.

The Partal Palace

The Palacio del Partal (Partal Palace) was built in the early 14th century and is also known as del Pórtico (Portico Palace) because of the portico formed by a five-arched arcade at one end of a large pool. It is one of the oldest palace structures in the Alhambra complex.

Generalife

The Nasrid rulers did not limit themselves to building within the wall of the Alhambra. One of the best preserved Nasrid estates, just beyond the walls, is called Generalife (from the Arabic, Jannat al-arifa). The word jannat means paradise and by association, garden, or a place of cultivation which Generalife has in abundance. Its water channels, fountains and greenery can be understood in relation to passage 2:25 in the Koran, “…gardens, underneath which running waters flow….”

In one of the most spectacular Generalife gardens, a long narrow patio is ornamented with a water channel and two rows of water fountains. Generalife also contains a palace built in the same decorative manner as those within the Alhambra but its elaborate vegetable and ornamental gardens made this lush complex a welcome retreat for the rulers of Granada.

Interior and exterior re-imagined

To be sure, gardens and water fountains, canals, and pools are a recurring theme in construction across the Muslim dominion. Water is both practical and beautiful in architecture and in this respect the Alhambra and Generalife are no exception. But the Nasrid rulers of Granada made water integral. They brought the sound, sight and cooling qualities of water into close proximity, in gardens, courtyards, marble canals, and even directly indoors.

The Alhambra’s architecture shares many characteristics with other examples of Islamic architecture, but is singular in the way it complicates the relationship between interior and exterior. Its buildings feature shaded patios and covered walkways that pass from well-lit interior spaces onto shaded courtyards and sun-filled gardens all enlivened by the reflection of water and intricately carved stucco decoration.

More profoundly however, this is a place to reflect. Given the beauty, care and detail found at the Alhambra, it is tempting to imagine that the Nasrids planned to remain here forever; it is ironic then to see throughout the complex in the carved stucco, the words, “…no conqueror, but God” left by those that had once conquered Granada, and would themselves be conquered. It is a testament to the Alhambra that the Catholic monarchs who besieged and ultimately took the city left this complex largely intact.

The Ardabil Carpet

Old, beautiful and important

The Ardabil Carpet is exceptional; it is one of the world’s oldest Islamic carpets, as well as one of the largest, most beautiful and historically important. It is not only stunning in its own right, but it is bound up with the history of one of the great political dynasties of Iran.

About carpets

Carpets are among the most fundamental of Islamic arts. Portable, typically made of silk and wools, carpets were traded and sold across the Islamic lands and beyond its boundaries to Europe and China. Those from Iran were highly prized. Carpets decorated the floors of mosques, shrines and homes, but they could also be hung on walls of houses to preserve warmth in the winter.

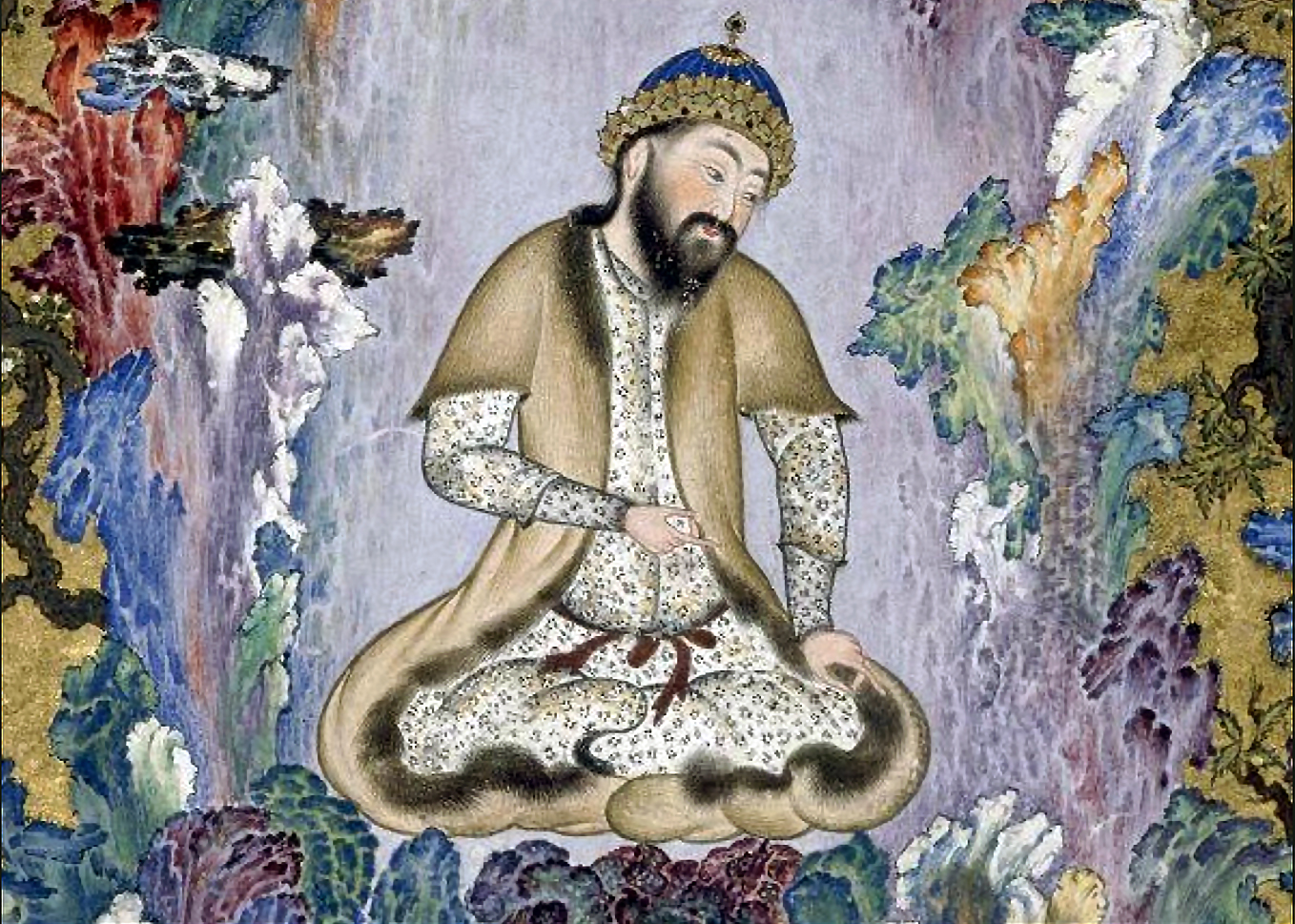

Ardabil and a 14th century saint

The carpet takes its name from the town of Ardabil in north-west Iran. Ardabil was the home to the shrine of the Sufi saint, Safi al-Din Ardabili, who died in 1334 (Sufism is Islamic mysticism). He was a Sufi leader who trained his followers in Islamic mystic practices. After his death, his following grew and his descendants became increasingly powerful. In 1501 one of his descendants, Shah Isma’il, seized power, united Iran, and established Shi’a Islam as the official religion. The dynasty he founded is known as the Safavids. Their rule, which lasted until 1722, was one of the most important periods for Islamic art, especially for textiles and for manuscripts.

Made for a shrine

This carpet was one of a matching pair that was made for the shrine of Safi al-Din Ardabili when it was enlarged in the late 1530s. Today the Ardabil carpet dominates the main Islamic Art Gallery in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, while its twin is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The carpets were located side by side in the shrine.

The pile of the carpet is made from wool, rather than silk because it holds dye better. The knot-count of a carpet still directly impacts the value of carpets today; the more knots per square centimeter, the more detailed and elaborate the patterns can be. The dyes used to color the carpet are natural and include pomegranate rind and indigo. Up to ten weavers could have worked on the carpet at any given time. The Ardabil carpet has 340 knots per square inch (5300 knots per ten centimeters square). Today, a commercial rug averages 80-160 knots per square inch, meaning that the Ardabil carpet was highly detailed. Its high knot count allowed for the inclusion of an intricate design and pattern. It is not known whether the carpet was produced in a royal workshop, but there is evidence for court workshop in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Design and pattern

The rich geometric patterns, vegetative scrolls, floral flourishes, so typical of Islamic art, reach a fever pitch in this remarkable carpet, encouraging the viewer to walk around and around, trying to absorb every detail of design.

That the design of the carpet was not arbitrary or piecemeal, but was well-organized and thoughtful can be seen throughout. Considering the immense size of the carpet—10.51m x 5.34m (34′ 6″ x 17′ 6″)—this is impressive. A central golden medallion dominates the carpet; it is surrounded by a ring of multi-colored, detailed ovals. Lamps appear to hang at either end.

The carpet’s border is made up of a frame with a series of cartouches (rectangular-shaped spaces for calligraphy), filled with decoration. The central medallion design is also echoed by the four corner-pieces.

Art historians have debated the meaning of the two lamps that appear to hang from the medallion. They are of different sizes and some scholars have proposed that this was done to create a perspective effect, meaning that both lamps appear to be the same size when one sat next to the smaller lamp. Yet, there is no evidence for the use of this type of perspective in Iran in the 1530s, nor does this explain why the lamps were included. Perhaps they were included to mimic lamps found in mosques and shrines, helping the viewer to look deeply into the carpet below them and then above them, to the ceiling where similar lamps would have hung, creating visual unity within the shrine.

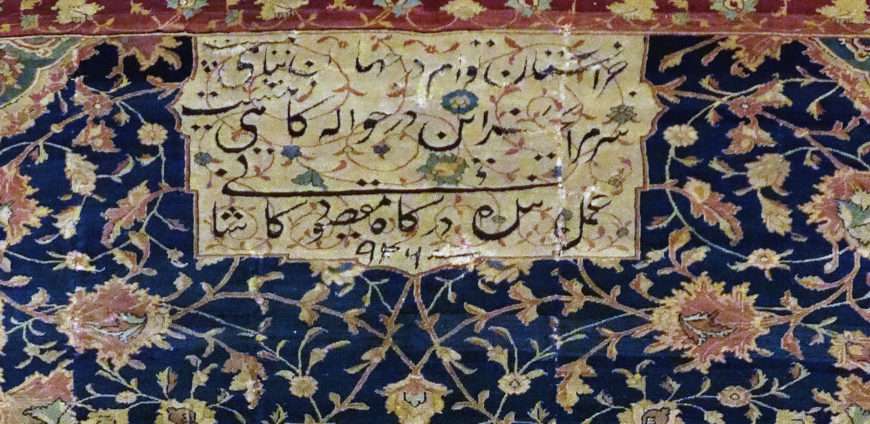

An inscription

The Ardabil Carpet includes a four-line inscription placed at one end. This short poem is vital for understanding who commissioned the carpet and the date of the carpet.

The first three lines of poetry reads:

Except for thy threshold, there is no refuge for me in all the world.

Except for this door there is no resting-place for my head.

The work of the slave of the portal, Maqsud Kashani.

Maqsud was probably the court official charged with producing the carpets. By referring to himself as a slave, he may be presenting himself as a humble servant. The Persian word for a door can be used to denote a shrine or royal court, so this inscription may imply that the royal court patronized the shrine. The carpets would have probably taken four years to make.

The fourth line of the inscription is also important. It provides the date of the carpet, AH 946. The Muslim calendar begins in the year 620 CE when Muhammad fled from Mecca to Medina; this year is known as the year of the Hijra or flight (in Latin anno hegirae). AH 946 is equivalent to 1539/40 CE (the lunar Muslim calendar does not exactly match the Gregorian Calendar, used in the west).

The design of the Ardabil carpet and its skillful execution is a testament to the great skill of the artisans at work in north-west Iran in the 1530s.

Medallion Carpet, The Ardabil Carpet (detail with edge), Unknown artist (Maqsud Kashani is named on the carpet’s inscription), Persian: Safavid Dynasty, silk warps and wefts with wool pile (25 million knots, 340 per sq. inch), 1539-40 C.E., Tabriz, Kashan, Isfahan or Kirman, Iran (Victoria and Albert Museum) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

How the carpet came to the V&A

Many great treasures from around the world have legally made their way into the collections of western museums. Many objects were legally purchased by collectors and museums in the 19th and 20th centuries; however, many works of art are still illegally exported and sold. British visitors to the shrine in 1843, noted that at least one carpet was still in situ. Approximately thirty years or so later, an earthquake damaged the shrine, and the carpets were sold off.